Comments to Attorney-General’s Department Regarding Australia’s Privacy Act Review

Contents

Data Flows, Data Localization, and Interoperable Domestic and Global Data Governance 3

The False Promise of Data localization. 5

Global Cross Border Privacy Rules and Global Data Governance 16

Overview

Australia’s Privacy Act review is happening as the global debate about data flows, governance, privacy, cybersecurity, and trade heats up with growing points of friction, and potential interoperability, emerging between different countries and regions. This submission focuses on how Australia’s revised Privacy Act (the Review Report) should be amended to manage issues and initiatives related to cross-border data flows and global data governance (namely, proposals 23.2 and 23.5).[1] This overview provides a summary of recommendations and key points.

Australia should remain committed to a principles-based approach to data privacy and to the principles of accountability and interoperability in designing how its domestic laws interact with global data transfers. Australia should avoid setting up a “whitelist” approach for allowing data flows to countries that provide a comparable level of data privacy. A whitelist approach reveals a limited regulatory view of how data flows, and the principle of accountability, work in practice. Data transfers have little to do with the whitelists that many countries have created, as regulators are unable to maintain their integrity or credibility, and over time, these tend to degrade into greyish lists. Many countries that use a whitelist approach fail to develop and use a clear, common, and consistent criteria for listing or delisting countries. In some cases, countries don’t even have a criterion—their listing is seemingly arbitrary. Some of these same countries haven’t added countries to their lists for the same reason in terms of lacking a clear, common, and consistent criteria. This makes many lists either meaningless or arbitrary and thus difficult to compare. This leads to an increasingly large and complicated “spaghetti bowl” of country lists. Ultimately, the proliferation of meaningless whitelists doesn’t add to good global data governance but rather makes it harder. There is another reason for avoiding this approach: foreign companies doing business in Australia must obey Australia privacy law if they process the data outside of Australia. As long as the company has legal nexus in Australia, Australian privacy authorities have legal jurisdiction.

Australia should also reject forced local data storage requirements (known as data localization). Yet Australian policymakers sometimes fall for the false promise of forced local data storage.[2] The data localization section of the Review Report (Section 23.2.4) was supportive of data localization, which is both misguided and highly problematic. Data localization does not lead to better data privacy, protection, and cybersecurity. As more countries enact updated data protection frameworks, it is nearly inevitable that some policymakers will propose data localization, as they reflexively and mistakenly believe that the best way to protect data is to store it within a country’s borders. Australia is lamentably no different.

Australia’s new Home Affairs Minister Clare O’Neil recently made extensive, and highly problematic, comments about data localization and its potential role in Australia cybersecurity and data governance. This submission provides extensive analysis to show not only why localization is misguided from a privacy and cybersecurity perspective, but also incredibly costly from an economic, innovation, and trade perspective. Likewise, Australia’s National Data Security Action Plan reflected this misguided thinking around data localization and data sovereignty. Data protection is a legitimate effort to ensure the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of data.[3] For example, policymakers should seek to protect sensitive information from inadvertent disclosures. Sensitive information includes both personal data and non-personal data that, if revealed, undermines privacy, safety, economic, and security interests. But data protectionism is not focused on preventing the disclosure of sensitive information. Instead, it is focused on preventing those outside the country from generating value from data.[4] This directly contravene’ s Australian economic and trade interests and trade law commitments. Moreover, data protectionism does nothing to enhance data protection. Requiring data be stored in-country (or with domestically owned companies) does not impact the overall security (or privacy) of data. Moreover, it can lead to reciprocal retaliatory measures from other nations, that would mean that Australia companies would have to keep data in other nations they are doing business in.

As Australia considers changes to the Australian Privacy Principles, it should not copy-and-paste the European Union’s (EU) General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in a misguided effort to seek an adequacy determination. GDPR has obviously had an impact on the review of Australia’s Privacy Act. However, Australia should be very careful and selective about what parts of GDPR it adopts and conduct a cost-benefit analysis on each provision. GDPR includes many costly and misguided provisions. For example, ITIF’s reports “The Costs of an Unnecessarily Stringent Federal Data Privacy Law” and “Maintaining a Light-Touch Approach to Data Protection in the United States” provides useful reference material in estimating the considerable costs of similar, individual GDPR provisions being enacted in the United States.[5] Australia should also avoid enacting a similarly misguided, slow, selective, and unrealistic process as the EU’s adequacy determinations in trying to force other countries to harmonize their privacy system to Australia’s approach. This submission details the problems of seeking and following the EU’s GDPR and its top-down, country-by-country effort to harmonize other countries’ laws to GDPR provisions via adequacy determinations.

Finally, Australia should clearly and explicitly support the new Global Cross Border Privacy Rules (CBPR) initiative. It was disappointing, and surprising, to see that the Review Report did not include a proposal to reference Global CBPR, especially given that Australia is a member. Global CBPR is a principles-, accountability-, and interoperability-based approach to protecting data privacy and data flows. It will be a critical mechanism to building an open, rules-based, and innovative global digital economy. Many of Australia’s closest trading and strategic partners are involved in Global CBPR, such as Canada, Japan, the United States, Singapore, and United Kingdom. This submission makes the case for Australia to ensure its revised Privacy Act doesn’t conflict with the new Global CBPR and provides an on-ramp to formally recognize it when it is launched.

Data Flows, Data Localization, and Interoperable Domestic and Global Data Governance

Australia Should Avoid Joining the Spaghetti Bowl of Country “Whitelists” That Provide a Comparable Level of Data Privacy

Proposal 23.2 of the Privacy Act Review paper proposes a mechanism to prescribe countries and certification schemes as providing substantially similar protection to the Australian Privacy Principles (APPs) under APP 8.2(a). Australia will be adding itself to the growing spaghetti bowl of countries that have whitelists of countries which provide a comparable level of privacy protection, thus allowing data transfers. However, a whitelist approach reveals a limited regulatory view of how data flows, and the principle of accountability, work in practice.

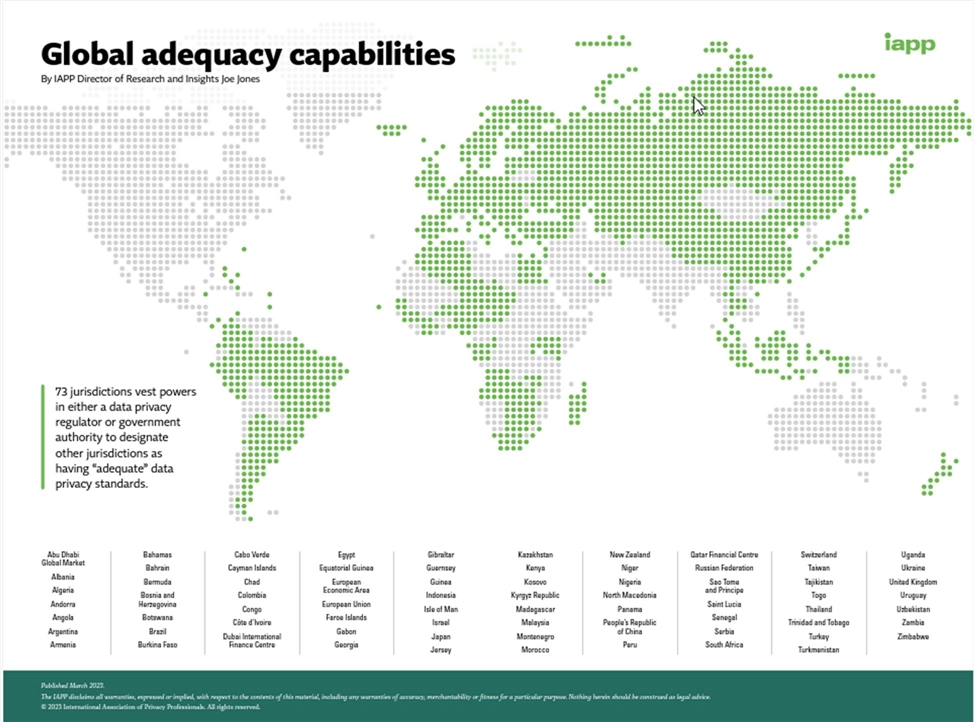

Figure 1 shows that the spaghetti bowl of country whitelists is growing in size and complexity, making legal compliance for firms incredibly difficult. There are 73 countries that designate (in one way, shape, or form) other jurisdictions as adequate or comparable. Data from Australia can go to countries A, B, and C, but data from A and C, can’t go to B, and so on and so forth. The lack of a clear, common, and consistent criteria (if any criteria exist, as many countries don’t make this clear) underpinning these assessments (many countries haven’t even named countries to their lists) has made many lists either meaningless or arbitrary and difficult to compare.

Figure 1: Global Adequacy Capabilities.[6]

The lack of a clear criteria means that many countries simply don’t list any countries, for fear of offending them, such as Malaysia. Other countries create a list without any criteria or transparency around their decision-making process, which they then arbitrarily change, such as what Colombia did. Other countries run a public submission process to assess what countries to add to their whitelist, but then don’t name any countries. As the Review Paper noted, the New Zealand Ministry of Justice undertook a public consultation on which countries should be prioritized for listing in late 2020 but no countries have yet been added to their list.

Australia should instead focus on reinforcing the accountability principle. The basic expectation should be that when it comes to handling data, companies doing business in a country should be responsible and held accountable under that nation’s laws and regulations, for both their own actions and the actions of their agents and business partners, regardless of whether they are located inside or outside the country where a firm collects or manages data. This accountability principle is based on two key points: A firm with “legal nexus” (which the Review Paper discusses) in a country’s jurisdiction has to abide by its data-related laws (even if the company transfers data abroad), and each country’s domestic data governance needs to be global in scope and interoperable in practice given the globally distributed nature of the Internet.

The Review Paper states the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) emphasized the importance of ensuring effective enforcement mechanisms for breaches by overseas entities and that this is why Australia should pursue adequacy determinations and other legal mechanisms. Australia should not expect other countries to be responsible for enforcing Australian privacy laws, as much as it does not expect to enforce other countries’ privacy laws. The main issue should be whether the entity managing Australian personal data has a legal nexus in Australia. This lies at the heart of the accountability principle. The focus for policymakers in making data-related laws and regulations is ensuring they hold firms accountable, regardless of where firms store, process, or transfer data.

For example, the majority of companies in the United States must disclose certain data-privacy practices and adhere to those requirements, even when processing data outside the country, as they remain responsible for the data regardless of where it is processed. U.S. companies mitigate these risks by stipulating requirements in relevant data-handling and processing contracts they implement with other companies. For example, foreign companies operating in the United States must comply with the privacy provisions of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), which regulates U.S. citizens’ privacy rights for health data—even if they move data outside the United States. And, if a foreign company’s affiliates overseas violate HIPAA, then U.S. regulators can bring legal action against the foreign company’s operations in the United States.

No doubt, domestic regulators need the support and resources to fully operationalize such a framework in order to give them greater confidence in their ability to enforce local laws in the Internet era. In part, this can be done through additional international mechanisms that support the development and application of shared principles and cooperation between regulatory authorities. There is obviously room for improvement in facilitating greater cooperation between different countries’ privacy regulators. One example is the Global Privacy Enforcement Network, which was launched in 2010 by the privacy authorities of 12 countries, including the United States, Australia, Canada, France, Germany, and the United Kingdom.[7] Another is the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Cross-border Privacy Enforcement Arrangement (CPEA), which creates a regional framework for information sharing and cooperation on enforcement among privacy regulators.[8] The new Global CBPR would be another mechanism. At the next level below this, privacy regulators can set up bilateral arrangements (e.g., memorandums of understanding) with counterparts. Countries can then use these and bilateral mechanisms to both share information and best practices, and cooperate on joint investigations, such as what the U.S. Federal Trade Commission has implemented with over a dozen countries.[9]

The False Promise of Data localization

Policymakers are often mistakenly told that “data is the new oil.” Yes, like oil, data is a valuable input to the economy. But unlike oil, data is non-rivalrous—one party using data does not reduce the amount of data available for others to use. And unlike oil, data is non-fungible—one piece of data cannot be substituted for another the way barrels of oils are interchangeable. Unfortunately, the “data is oil” analogy has led to some poorly conceived policy ideas, in particular the idea of data localization and data sovereignty.

Australia’s National Data Security Action Plan unfortunately reflected this misguided thinking around data localization and data sovereignty. It declares that “Australia’s data is a valuable national asset requiring robust security settings” and that “inadvertently allowing another country to access Australia’s most critical data will erode our sovereignty and control over that data in the long term.” In other words, Australian policymakers are trying to lock down domestic data out of concern that foreign actors may exploit it for unfair economic gain. However, in all cases, data sovereignty is thinly disguised protectionism. Indeed, these policies often gain traction because many policymakers conflate data protection and data protectionism.

Data protection pertains to a legitimate effort to ensure the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of data. For example, policymakers should seek to protect sensitive information from inadvertent disclosures. Sensitive information includes both personal data and non-personal data that, if revealed, undermines privacy, safety, economic, and security interests. For example, sensitive information could be personal data about a person’s health that reveals information the individual would prefer to keep private; intellectual property (IP), including trade secrets, that businesses want to protect; or non-personal information such as classified government data that undermines national security. In these cases, stronger data protection measures, particularly enhanced technical safeguards and better cybersecurity practices, can help prevent data breaches or other unintentional disclosures of sensitive information, including to foreign governments or firms.

But data protectionism is not focused on preventing the disclosure of sensitive information. Instead, it is focused on preventing those outside the country from generating value from data. While the goal of these policies is to maximize value for domestic companies, the net impact of these restrictions is almost certainly negative. The problem is that most data have little to no value until businesses do something with it. Therefore, the more businesses can gain access to data, the more value can be generated. Restricting foreign firms from accessing domestic data limits the potential universe of businesses that can add value to data. That means data holders—whether they are consumers or businesses—miss out on opportunities to benefit, directly or indirectly, from their data.

Moreover, data protectionism does nothing to enhance data protection. Requiring data be stored in-country (or with domestically owned companies) does not impact the overall security of data. Australian data, for example, is not more secure in an online service simply because that service is owned and operated by an Australian company rather than an American one. The security of the online service depends on a series of technical, legal, and physical controls at the company. Countries that pursue data protectionism risk reciprocal actions by other governments. For example, Australian mining giant Rio Tinto collects data from around the world as part of its smart mining program to analyze geology, optimize energy use, and automate its autonomous equipment. If other governments prohibited Rio Tinto from sending data back to Australia it would have a negative impact on the company.

Proponents think that forcing firms to store data locally enhances the state’s agency and that of their own firms and people. At best, the agency gained by data localization is illusory. In many cases, it is counterproductive. And in cases like Australia—which is a middle-sized economy that depends on global data flows and digital trade to build critical economies of scale, and which has actively supported efforts to build an open, rules-based, and innovative global digital economy—data localization undermines other important economic goals. It reeks of hypocrisy and opens a loophole for other countries to enact similar digital protectionism policies that would impact Australia firms. An embrace of data localization is not indicative of the enlightened style of leadership the worlds looks for Australia to bring to the global trading system.

Even those policymakers and advocates who support narrow, limited data localization rules are still often misguided about how cloud services and cloud security functions. For example, some policymakers support government agencies storing data on premise in the misguided pursuit of cybersecurity.[10] But data security depends on the technical, physical, and administrative controls implemented by the service provider, which can be strong or weak, regardless of where the data is stored. If the Australian government wants to ensure its most sensitive data is especially secure, it can specify detailed technical and control requirements in its procurement contracts, such as the use of international standards for cybersecurity, the use of specific encryption, and cloud-based hardware security modules. Government policymakers need to appreciate that leading cloud service providers invest huge amounts of resources in designing and maintaining cutting-edge cybersecurity measures as their business depends on it. The dynamic nature of cyber risks means that they need to do this continuously. Furthermore, the global operations of leading cloud firms actually improve their ability to protect data, as they have to defend against all manner of threats (as compared to just a local firm) and can leverage their global services to secure data, such as through the use of “data sharding” and other technologies.

Misguided Motivations Used to Justify Data Localization

Data localization does not provide better data privacy, data protection, or cybersecurity. Nor does it provide the basis for digital development. Nor does it provide the silver bullet for government agencies that want to require data localization to ensure they have access to data for law enforcement, financial oversight, and other concerns. This section analyzes and refutes several misguided motivations policymakers use to justify data localization.

Misguided Data Privacy, Protection, and Cybersecurity Concerns

As more countries enact updated data protection frameworks it is nearly inevitable (like Australia and its National Data Strategy) that some policymakers will propose data localization, as they reflexively and mistakenly believe that data is more private and secure when it is stored within a country’s borders. This misunderstanding remains at the core of many data localization policies. However, in most instances, data localization mandates do not increase commercial privacy nor data security.[11]

Evidence showing that data localization does not provide greater data privacy or security has only become starker in recent years. Firstly, most companies doing business in a nation—all domestic companies and most foreign ones—have “legal nexus,” which puts the company in that country’s jurisdiction. This is crystal clear for firms in financial, payment, and other heavily regulated sectors, given the need to apply for licenses to operate. Whichever sector a firm is in, a central basic fact remains: companies cannot simply escape from complying with a nation’s data-related laws by transferring data overseas.

Second, policymakers focusing on geography to solve privacy and cybersecurity concerns misunderstand how these play out in today’s digital economy. Or they’re disingenuous. Consumers and businesses rely on contracts or laws to limit voluntary disclosures to ensure that data stored abroad receives the same level of protection as data stored at home. In the case of inadvertent disclosures of data (e.g., security breaches) and other cybersecurity issues, to the extent nations have laws and regulations, again, a company operating in the country is subject to those laws, regardless of where the data is stored.

Despite it being perhaps one of the most clearly misguided motivations, the mistaken notion about localization and data security persists. Having complete and direct ownership and control of the IT systems “stack,” from the building floor and walls to the software on the servers, makes people feel that their data is as secure as possible. But this provides a false sense of security. Most cybersecurity vulnerabilities are exploited remotely, so the physical location of data has little to no impact on cyber threats (as demonstrated by the hack of the U.S. Office of Budget and Management).[12] Furthermore, inadvertent disclosures of data are the result of security failures, such as hackers breaking into a corporate network to steal data, government agencies tapping into telecommunications links, or employees mistakenly posting sensitive data in a public forum. If IT systems are in any way connected to the Internet, they are at some degree of risk.

Policymakers misunderstand that the confidentiality of data does not generally depend on which country the information is stored in, only on the measures used to store it securely. A secure server in Malaysia is no different from a secure server in the United Kingdom. Data security depends on the technical, physical, and administrative controls implemented by the service provider, which can be strong or weak, regardless of where the data is stored.

Policymakers’ focus on the location of data storage, in part, as they do not want to tackle the more-challenging factors that actually contribute to good cybersecurity, such as building greater cybersecurity awareness by users and firms and encouraging firms and government agencies to adopt and remain committed to best-in-class cybersecurity practices and services. Good cybersecurity is just as much about the people involved in managing, protecting, and accessing the data as it is about the data itself, as personnel are central to most cybersecurity incidents, such as the failure to update vulnerable systems or credentials being lost via phishing attacks.

Moreover, data localization actually undermines cybersecurity. First, it prevents the sharing of data to identify IT system vulnerabilities and help firms detect and respond to cyber attackers. For example, in 2020, India’s Securities and Exchange Board released a cybersecurity circular that required financial firms to localize a broad range of data that would do just this.[13] Firms need to share data to reconcile if cyberattacks (such as in India) are new or known. Sharing system vulnerability information also allows cybersecurity providers to identify vulnerabilities.

Second, data localization precludes cloud service providers from using cybersecurity best practices, such as through “sharding,” where data is spread over multiple data centers. This gets to the broader point—while cloud computing does not guarantee security, it will likely lead to better security because implementing a robust security program requires resources and expertise, which many organizations (especially small and medium-sized ones) lack. But large-scale cloud-computing providers are better positioned to offer this protection. For example, advanced cloud providers provide their users with advanced encryption tools to allow them to retain and use the keys before data is uploaded, thereby preventing third parties, including the cloud companies themselves, from accessing their data.[14]

Data Localization and Data/Cyber Sovereignty

Digital protectionism remains a key motivation behind many countries enacting data localization policies, but it has been subsumed into a broader narrative around digital/cyber sovereignty and control in recent years. This a broader trend that Australia should both avoid and be actively working to counter given the threat it poses to its interests in building an open, rules-based global digital economy at the World Trade Organization (WTO) and via other bilateral and regional trade agreements.

Many policymakers and governments around the world are pursuing a data, digital, and cyber sovereignty approach that is often built on the misguided attraction to the false sense of “control” and sovereignty provided by data localization. It’s no surprise that authoritarian countries like China and Russia are the most significant users of these concepts (and data localization practices) as it aligns with their main political interests—maintaining power through access and control over data. Both countries frequently cite sovereignty as part of advocacy to create a top-down, state-directed global Internet (as opposed to the open, multi-stakeholder-based approach favored by democratic countries).

Europe is a leading offender. European leaders such as former Germany Chancellor Merkel and French President Macron have explicitly called for both digital protectionism and data sovereignty.[15] The fact that senior European policymakers think that data stored on a foreign cloud service represents lost sovereignty shows how little some understand about how firms manage data and how much they prioritize this misguided sense of control.[16] Europe tries to position itself as a moral leader of digital regulation, using concerns over data privacy and artificial intelligence (AI) to cloak discriminatory and restrictive policies. Europe’s protectionist intent appears in nearly every digital policy proposal. Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation is evolving into the world’s most significant de facto data localization framework. Europe’s draft data strategy pushes for data localization and asserts that the European Union (EU) needs cloud providers owned and operated in Europe.[17] Similar points are made in Europe’s white paper on AI.[18] It is also evident in the proposal for a European cloud via GAIA-X.

The EU’s GDPR and Adequacy Determinations: A Costly, Misguided, and Inconsistent Approach to Privacy and Data Transfers

Section 23.3 of the Review Report focuses on the EU’s GDPR. This section details the costly and misguided pursuit of copying-and-pasting the GDPR into Australian law and in pursuing an EU adequacy determination or adopting some similar adequacy-based approach in Australia. The DPI Report recommended that reforms to the Act have should be revised such that it could be considered by the European Commission to offer ‘an adequate level of data protection’ to facilitate the secure flow of information to and from overseas jurisdictions such as the EU. This would be a mistake.

The GDPR reflects the EU’s approach to securing what it sees as its citizens’ fundamental rights to privacy and protection of personal data. The Review Report rightly points toward the central point that Australia’s Privacy Act retain its principles-based focus on consumer protection as opposed to the EU’s rights-based approach to privacy.[19] A rights-based approach lends itself to the EU’s absolutist/fundamentalist approach to data privacy—where privacy generally trumps all other interests and values—when data actually involves many rights and interests, such as national security, innovation, and trade. In line with this, the APEC Privacy Framework states that: “national data protection laws should avoid (or remove) clear obstacles to trade and innovation.”[20] A principles-based approach to data policy generally leads to a more balanced, rather than absolutist, outcome. Countries that use a principles-based approach to privacy have far less issues working together as they recognize that there is no one data privacy law and that privacy interests inevitably need to be balanced against other interests. Australia is trade-orientated, so needs data governance systems that align with those of other countries.

The following section details why the GDPR is costly and why adequacy determinations represent a misguided and costly data transfer tool. It also shows how the EU’s inconsistent application of the GDPR’s privacy principles is evidence of its shortcomings.

GDPR Is Costly

The Review Report stated that submissions rightly pointed out that an adequacy assessment could require major legislative changes and that organizations would bear a regulatory cost in stepping up to GDPR standards. There is substantive research and papers into the costs of GDPR, such as the University of Oxford’s Privacy Regulation and Firm Performance: Estimating the GDPR Effect Globally.[21] The Center for Data Innovation has also summarized a range of other studies in “What the Evidence Shows About the Impact of the GDPR After One Year” and “A New Study Lays Bare the Cost of the GDPR to Europe’s Economy: Will the AI Act Repeat History?.”[22]

Data privacy laws impose costs on organizations that are required to comply with the laws’ provisions. The extent of these costs, and the burden they place on organizations, depends on which provisions are included in a given law, as well as the law’s enforcement mechanisms. Estimates of the cost of privacy legislation factor in two types of costs. The first is compliance costs that laws directly impose on organizations by requiring them to comply with certain provisions. These provisions may include requirements to hire and retain data protection officers, conduct privacy audits, build and maintain data infrastructure, and ensure data access, portability, deletion, and rectification for users. Some of these may be fixed costs, such as creating a process and infrastructure for handling data deletion requests, whereas others may be variable costs, such as the cost to respond to each deletion request.

The second set of costs is “hidden costs.” These encompass the costs of less productivity and innovation in industries powered by data—which, in today’s economy, is virtually every industry. Examples of hidden costs include lower consumer efficiency, less access to data, and lower ad effectiveness. While compliance costs affect every individual organization covered under a law’s purview, hidden costs affect the entire economy.

The difference between a broad data privacy law and a more tailored law, in terms of economic impact, is significant. For example, ITIF research conducted in 2019 determined that U.S. federal legislation mirroring key provisions of the GDPR could cost the U.S. economy approximately $122 billion per year, whereas a more focused, but still effective national data privacy law would cost about $6 billion per year, around 95 percent less.[23] This includes both direct regulatory compliance costs of up to $17 billion and indirect “hidden” costs of up to $106 billion.[24]

One argument for replicating the GDPR’s approach to data privacy in Australia is that it would be efficient because organizations that already have to comply with the GDPR’s rules would not have to also comply with a competing set of rules. However, this argument not only does not consider hidden costs, which are unrelated to compliance and are instead a result of the economic impact of less productivity and innovation—an inevitable consequence of GDPR-like privacy rules—but it also fails to differentiate between multinational and non-multinational organizations, and fixed and variable compliance costs.

The cost savings associated with a GDPR-like law in Australia would only apply to multinational organizations that have users or conduct transactions in the EU. Non-multinational organizations that only operate in Australia or in non-EU foreign markets do not have to comply with the GDPR’s rules. An overly broad, GDPR-like Australian law would pose significant new compliance costs on these organizations.

Additionally, both multinational and non-multinational organizations still have to pay new variable costs. Many of the compliance costs a GDPR-like law would impose are fixed costs, such as hiring and retaining data protection officers, conducting privacy audits, and some of the costs associated with ensuring data access, portability, deletion, and rectification. But there are also variable costs associated with ensuring data access, portability, deletion, and rectification, and these costs would significantly increase for multinational organizations that already operate in the EU were the United States to pass a GDPR-like data privacy law. The cost of duplicative enforcement—especially a private right of action—would also affect both multinational and non-multinational organizations.

Adequacy Determinations—Misguided, Slow, and Inconsistent

It would be a mistake for Australia to follow the EU’s use of adequacy determinations in an effort to manage cross-border data flows and data privacy. At the heart of the problem is that adequacy determinations aim for data privacy harmonization rather than interoperability.

The European Commission (EC) can issue adequacy decisions in relation to third countries to alleviate the GDPR’s general prohibition on transfers on EU personal data. The Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) observed that a finding of adequacy requires the third country privacy regime in practice to ensure protection of personal information that is “essentially equivalent” to the EU system.[25] But the adequacy process is uncertain, opaque, and seemingly ad hoc. The EU relies on adequacy determinations as its main tool to manage international transfers of EU personal data as it effectively makes other countries responsible for enforcing EU data protection rules. GDPR and EU jurisprudence (especially due to the Schrems I and II court cases at the CJEU) sets a high bar for data transfers, which forces the EU to push other countries to harmonize to GDPR (as otherwise it’s difficult for agreements to survive legal challenges in the EU). The EU’s approach means that the group of countries that could reach their high bar, and be willing to do so, is very small. In the 25 years since Directive 95/46/EC on Data Protection came into effect in 1995, and with it, the concept of adequacy decisions, only 12 countries have obtained an adequacy decision. These are: Andorra (2010); Argentina (2003); Faeroe Islands (2010); Guernsey (2003); Israel (2011); Japan (2019); Jersey (2008); New Zealand (2013); Isle of Man (2004); Switzerland (2000); Uruguay (2012), and the United Kingdom (2021). Most of these relate to micro-states, former colonies, and minor trading partners, with no broader rhyme, rhythm, or pattern. Meanwhile, Canada and the United States (hopefully forthcoming, via the Transatlantic Data Privacy Framework) only have “partial” adequacy.

A major problem is that the EU’s application of its privacy principles is not consistent. Adequacy decisions take into account the circumstances of the third country under consideration, and its relationship with, and importance to, the EU. However, this has not been the case. Canada and the United States are key trading partners and developed economies with their own data protection frameworks, yet they only get partial adequacy determinations. Yet other minor trading and political partners with less effective data protection frameworks get a full determination and inconsistent scrutiny. This is before one evens get to the issue of government access to data, where the United States does a much better job than many EU member countries. In the case of Argentina, the adequacy decision was granted despite the Article 29 Working Party (the now-European Data Protection Board (EDPB)) expressing concerns about weaknesses in Argentinian data protection laws. Another example of this appeared in the Article 29 Working Party’s report on New Zealand, which dismissed concerns about deficiencies in New Zealand's onward transfer laws on the basis that, given its geographical distance from Europe, its size and the nature of its economy, it was unlikely that those deficiencies would have much practical effect on EU data subjects.[26] Furthermore, it is inconceivable China would ever be deemed “adequate” from a European perspective. Yet, the fact that Europe has not applied to China the same standards it applies to the United States with regard to EU personal data highlights the brazenly arbitrary nature of its approach.[27] As long as certain parts of the adequacy procedure are kept opaque and applied inconsistently, it gives rise to the criticism that the EC acts biased and applies a more or less rigorous assessment based on political considerations.

The lack of adequacy decisions belies the fact that many Asia-Pacific jurisdictions now have national data protection legislation, including Australia, Hong Kong, Japan, Macau, Malaysia, New Zealand, the Philippines, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan. The recently completed EU-Singapore free trade agreement represents an example of the EU’s inconsistent application of its privacy principles and the limits of the adequacy-based approach. The agreement includes little to nothing on digital trade, data flows, and privacy, despite the fact that Singapore is a developed country with a sophisticated national data protection framework, and a track record of working with key trading partners on data governance and privacy in trade agreements. In 2018 (the year the deal was completed) Singapore was the EU’s largest goods trading partner in Southeast Asia, thus showing it’s an important trading partner as per the EU criteria for adequacy determinations.

Yet, on e-commerce, the EU and Singapore make non-binding commitments to recognize the importance of the free flow of information on the Internet and that that the development of electronic commerce must be fully compatible with international standards of data protection, in order to ensure the confidence of users of electronic commerce.[28]Article 8.54 on data processing includes commitments on data transfers and protections for financial service providers.[29] If Singapore is not able to meet EU data protection standards, then what chance do other developing countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America stand?

Putting this aside, the limited number of adequacy decisions is also because the cost and complexity for a country to live up to GDPR is high—and getting higher with the EU’s own evolving interpretation, application, and enforcement. For many countries considering adequacy, an adequacy decision may not alleviate the administrative impact of GDPR on data transfer (as GDPR intended), given what equivalence means for these countries and their firms in having to harmonize their own data protection frameworks and practices to GDPR. Never mind the fact that adequacy decisions are “living” documents, with periodic review at least every four years, thus meaning that a country and its firms face the added cost and complications of potentially enacting changes every few years to live up to GDPR.

Thus, the legal and regulatory capacity for counterparts to live up to the EU’s ever-changing standards is considerable. Furthermore, few businesses would want to go through such a process if it only made it easier to transfer EU personal data to just those few countries covered by adequacy. Ongoing uncertainty and challenges in the implementation and enforcement of GDPR in the EU makes it likely that future adequacy decisions will be even more difficult to obtain. Given this, it is hard to see many countries outside the European Economic Area meeting the standards and enhanced protections of GDPR and would want to do so.

The 12 adequacy decisions previously made under the 1995 Directive have so far been allowed to continue in effect under GDPR, despite the fact that it contains many novel provisions and the level of scrutiny that the EC applies for new adequacy decisions is often much higher.[30] Thus far the EU has not reconsidered its adequacy decision with countries that are unlikely to meet the EU’s new and changing standards under GDPR standards. One example is Israel’s recent initiative to source data without users’ explicit consent, as it adopted regulations allowing the police to use the country’s anti-terrorism location tracking systems to track COVID-19 positive individuals’ mobile phones.[31] The only privacy safeguards seem to be based on trusting the government’s promise to use the data in a “focused, time-limited, and limited activity.” EU commissioner Vera Jourová seems to have put Israel and China (which has extensive, unchecked surveillance of its citizens) in the same bucket by declaring “We definitely will not go the Chinese or Israeli way, where the use of these technologies to trace the people goes beyond what we want to see in Europe,” but there are no signs that adequacy with Israel is under review as a result.[32]

The critical flaw at the heart of the EU’s approach is the logic that the adequacy determination’s country-by-country approach is effective in promoting better data privacy and protection by companies that manage personal data.[33] Going country-by-country to make them responsible for enforcing the EU’s approach to data protection, instead of ensuring that firms that manage EU personal data use and protect it as per EU laws—wherever this takes place—is inevitability going to be very slow and limited. Most other leading digital economies with privacy laws, such as the United States, Canada, Mexico and Japan, do not impose material restrictions on cross-border transfers of personal information. There is no one approach to data privacy. Countries manage data privacy differently due to differing social, cultural, and political values, norms, and institutions. Beyond political and commercial relations, the GDPR also requires that the EC take into account the rule of law, respect for human rights and freedoms, the availability of effective administrative and judicial redress for individuals whose personal data is being transferred, and the effectiveness of independent supervisory authorities with responsibility for enforcing the data protection rules. The EU’s adequacy-based approach to data privacy and data transfers is ultimately untenable—in the long-term in terms of building truly global and integrated data governance—as few countries can or will harmonize their data protection frameworks to a level that the EU finds acceptable.[34]

The Inconsistent Application of the EU’s Privacy Principles in Regard to Government Access to Data

The EU’s inconsistent application of privacy concerns is most clearly on display with regard to the issue of government access to data and surveillance. Government access to data is supposedly at the heart of adequacy determinations, yet it is sparingly applied. In support of its opinion in the Schrems II case at the EUCJ, the advocate general referred to Article 45(2) of GDPR, which states that the EC should consider the public authorities’ access to personal data in its assessment for adequacy, whereupon the possibility of foreign authorities’ processing of personal data shouldn’t be interpreted as meaning that the GDPR is inapplicable to the data transfer.[35]

Over the last decade, concerns over international transfers of personal data have been motivated in no small-part due to concerns over government surveillance, stemming from the Snowden revelations about the United States.[36] This was a fair reaction—up to a point. The United States revised surveillance and other laws that, collectively, went a considerable way toward addressing European concerns about U.S. surveillance practices.[37] However, while the United States has engaged with the EU on its national security laws and practices, and have subjected them to CJEU scrutiny, EU member states’ comparable behavior receives little to no attention. Nor has the EU applied the same scrutiny to data flows going to other countries where there are clearly issues over surveillance and government access to data, such as China and, most gallingly, Russia. While surveillance and national security are not EC competencies, thereby making it much harder for it to play a role in consistently applying its standards in the region, the EC does have the power and role to at least apply them consistently with trading partners.[38] Thus far, the EU has not done this. EU personal data still goes to countries with few genuine data privacy protections and no independent judicial oversight over government access to data.

This points to the underlying inconsistency of the EU’s adequacy-based approach to managing EU personal data flows. The EU and the United States have worked through concerns about the latter’s surveillance activities, which led to legislative and administrative changes. This was within the context of an adequacy agreement that is regularly reviewed and re-affirmed. But there has been no similar scrutiny of other countries with adequacy agreements (including Israel).

In China, the EU’s inconsistency is most transparently evident. The 2016 European Parliamentary report on China’s data protection framework reflects the EU’s selective application, stating that “one cannot talk of a proper data protection regime in China, at least not as it is perceived in the EU” and that:

If a legalistic approach was adopted, then no common ground could be found between two fundamentally different systems both in their wording and in their raison d’être. Consequently, data transfers would need to be prohibited towards China, on the basis of Article 25 of the EU 1995 Data Protection Directive. However, this would be an impractical, if not unnecessary position.[39]

While this is a European Parliamentary report, and thus does not reflect the European Parliament or EC’s official position, it illustrates the selective application of EU concerns over data protection and government access to data given the EU has not addressed this issue despite being well aware of it. Similarly, the European Data Protection Board’s (EDPB) report “Government Access to Data in Third Countries: Russia, China, and India” clearly detailed how China fundamentally didn’t protect EU data privacy, yet how the EU failed to take any action. This stands in stark contrast to the many years of major action and scrutiny against the United States, which has enacted major reforms to its surveillance system to address European concerns.[40]

EU-Vietnam relations are another recent example of the EU’s inconsistent application of its privacy concerns. Within the various and opaque criteria for EU adequacy decisions and trade policy objectives, it seems that trade and political concerns were significant enough to pursue a trade deal, but not enough to push for data protection changes in Vietnam as part of an adequacy determination.

On February 12, 2020, the European Parliament approved the EU-Vietnam trade and investment agreements.[41] This shows the EU is willing to make tradeoffs when it applies its approach to fundamental human rights, such as privacy and trade. This is despite the fact that the EU has criticized Vietnam for disrespecting fundamental rights, including the right to privacy.[42] Financial services is the only part of the EU-Vietnam agreement that deals with data and data transfers, which indicates where the EU is willing to push for binding rules.[43] This raises the question as to why the EU feels it can make commitments on financial data flows, which involve personal data, but not commitments on other types of data flows involving personal data.

Putting this and other political, social, and economic factors aside, just on the issue of government access to data, there are obvious red flags that should preclude Europeans’ personal data from being transferred to Vietnam—if the EU was to apply the same standards and scrutiny that it applied to the United States. Vietnam’s constitution provides that infringement of human rights for reasons of national security must be necessary and that the exercise of human rights may not infringe on its national interests.[44] On top of this, there’s an obvious lack of independent judicial oversight. There’s also a lack of effective remedies in the Vietnamese data protection regime, which together don’t provide the type of safeguards that the EU would no doubt want in terms of defending against unjustified data processing by the Vietnamese government.[45]

For example, the Law on Information Technology permits Vietnamese state agencies to access personal data.[46] In terms of national security, the recently adopted Cybersecurity Law (CSL) is critical as it appears to give the Vietnamese authorities a far-reaching right to access personal data.[47] To what extent the public authorities in Vietnam can access personal data under the CSL cannot be answered with certainty. Article 5 of the CSL lists the measures available to protect national security, and among other things, it entitles the authorities to evaluate, inspect, and supervise a firm’s cybersecurity. Furthermore, Article 26 of the CSL provides that companies providing services on telecom networks and the Internet must provide user information to the Ministry of Public Security when so requested.

Global Cross Border Privacy Rules and Global Data Governance

Australia should explicitly list the Global CBPR system in the Privacy Act or in subsequent regulatory guidance to send a signal to firms that it is a valid data transfer mechanism.

Global CBPR is exactly the type of interoperable, accountability-based system that Australia should support. This accountability-based approach is important because modern technology, especially the Internet and cloud data storage, means that each country’s domestic regulatory regime for data (such as for privacy) needs to be globally interoperable given that each country faces the same challenge in applying its laws to firms that may transfer data between jurisdictions. Interoperable privacy frameworks are the international extension of domestic accountability-based approaches to data privacy such that data is still able to flow between different privacy regimes, and countries’ data protection rules flow with it.

The Global CBPR system is attractive to a diverse range of countries as it focuses on core principles and accountability. The Global CBPR’s focus on interoperability reflects the fact that there will be no one globally harmonized privacy regime. It recognizes that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to privacy protections, as different countries have different legal and societal values and approaches to the issue. What Global CBPR helps ensure is that a country’s privacy rules travel with the data and that a company can commit to abide by these rules, wherever it stores the data. Global CBPR also helps ensure that these rules are enforced.[48] For a business, being Global CBPR-compliant means it is subject to one privacy regime for data transfers between countries that have joined the system.

Global CBPR and a Possible Future Bridge to the EU’s GDPR

Global CBPR, like its successor APEC CBPR, faces skepticism. Established over a decade ago, APEC CBPR was ahead of its time in terms of providing a tool for data transfers before major barriers were in place. It also faced legitimate criticism, as it took a long time for countries to join, and even then, not many firms signed up to it. However, the launch of Global CBPR provides an opportunity to revise and refresh the system to address these issues. Also, the development of Global CBPR (in terms of creating a secretariat and updating principles and processes) also opens a long-term potential path to building a bridge with the EU GDPR (if the EU is actually genuinely serious in trying to build interoperability).

The EU for the longest time refused to genuinely engage with APEC CBPR as its representatives pointed to ongoing GDPR reforms. Then once GDPR was enacted, the EC took to criticizing and patronizing APEC CBPR. In essence, privacy fundamentalists at the EC want GDPR to be the only model that countries look toward adopting. But if Global CBPR grows in membership countries and firms, it will become a true competitor as it is a far more realistic option for countries to join (as opposed to harmonizing data privacy laws to GDPR).

Global CBPR should be fully up-and-running before it considers how to connect with other data transfer regimes. However, it’s worth keeping in mind in the long term. A previous side-by-side comparison of binding corporate rules (BCR) and APEC CBPR demonstrates that they are substantially similar in their use of contracts as a tool for firms to maintain privacy standards in managing data across jurisdictions and in their participation criteria, both in terms of the underlying privacy principles and the content of the rules themselves, such as the requirement for privacy staff, privacy training, compliance management, and independent assurance of compliance.[49] This cross-over will likely remain the case with Global CBPR.

Perhaps CBPR’s global evolution and adoption will encourage the EU to genuinely work to build a connection between the two mechanisms. Ideally, a firm would perhaps have to undertake a few more steps for Global CBPR to be a valid data transfer mechanism in the EU. In the interests of pointing toward potential future alignment, the section below details key similarities and differences between CBPR and GDPR.

GDPR and APEC’s CBPR share a lot in common and, if connected, would provide a heightened level of data protection for a significant portion of the global economy. Both the EU Data Protection Directive and the APEC Privacy Framework recognize that safe transfers of personal information beyond their direct reach must be possible. However, the main means by which this is achieved in the EU is through adequacy findings at country-level or at company-level with model clauses, while in the APEC region they are recognized at the firm-level (in questions 46 and 47 of the APEC CBPR program requirements).[50] A side-by-side comparison of BCRs and APEC CBPR demonstrates that they are substantially similar in their use of contracts as a tool for firms to maintain privacy standards in managing data across jurisdictions and in their participation criteria, both in terms of the underlying privacy principles and the content of the rules themselves, such as the requirement for privacy staff, privacy training, compliance management, and independent assurance of compliance.[51]

However, there are some noteworthy operational differences between BCRs and APEC CBPR.[52] A major difference is their scope of operation. BCRs allow intra-company transfers as these are all subject to the same internal rules and external supervision (in the form of a relevant EU Data Protection Authority). However, international transfers outside the company require additional measures. APEC CBPR takes the next logical step by allowing for international inter-group transfers. That is, in addition to intra-group transfers, one CBPR-certified company in an APEC member economy can transfer personal information to another CBPR-certified company in a different member economy. The limitation of APEC CBPR is that transfers can only take place between the APEC economies participating in the CBPR system.[53] Another key challenge is to guarantee internal and external binding-ness—that is, European data subjects must be able to seek and receive redress if something goes wrong when their personal information is sent to a CBPR-certified company.[54]

Within APEC, the EU’s Article 29 Working Party and APEC’s Data Privacy Subgroup met on several occasions to try to facilitate increased cooperation between the two systems. The most tangible result was the joint release in March 2014 of a reference list on requirements for BCRs and CBPRs, which provides an informal “pragmatic checklist” that identifies the separate and overlapping requirements for organizations seeking certification under one or both systems.[55] At some point in the future, Global CBPR could restart work with the EDPB on developing a revised checklist and mechanism to build interoperability between the two systems.

Conclusion

Australia’s Privacy Act needs updating, but Australia needs to do this carefully given the enormous impact it has on the broader economy. It should carefully evaluate the cost-benefit of each and every provision. This is especially crucial for Australia given its existing exemption for SMEs and the clear cost that overly restrictive data privacy regimes like GDPR have on SMEs. Furthermore, Australia should do what the EU has not in proactively considering the international implications and connections of Australia’s data privacy regime and ensure that it’s aligned—from the start—with international principles, best practices, and emerging initiatives like Global CBPR.

Endnotes

[1] “Privacy Act Review Report,” Australia’s Attorney-General’s Department, February 16, 2023, https://www.ag.gov.au/rights-and-protections/publications/privacy-act-review-report.

[2] Daniel Castro, “False Promise of Data Nationalism (ITIF, December, 2023), https://www2.itif.org/2013-false-promise-data-nationalism.pdf.

[3] “National Data Security Action Plan: Discussion Paper,” Australian Government, https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/data-security/nds-action-plan.pdf.

[4] Daniel Castro, “Policymakers Should Distinguish Between Data Protection and Data Protectionism,” Innovation Files, May 31, 2022, https://datainnovation.org/2022/05/policymakers-should-distinguish-between-data-protection-and-data-protectionism/.

[5] Ashley Johnson and Daniel Castro, “Maintaining a Light-Touch Approach to Data Protection in the United States” (ITIF, August 8, 2022), https://itif.org/publications/2022/08/08/maintaining-a-light-touch-approach-to-data-protection-in-the-united-states/; Alan McQuinn and Daniel Castro, “The Costs of an Unnecessarily Stringent Federal Data Privacy Law” (ITIF, August 5, 2019), https://itif.org/publications/2019/08/05/costs-unnecessarily-stringent-federal-data-privacy-law/.

[6] Joe Jones, “Infographic: Global adequacy capabilities,” IAAP, March, 2023, https://iapp.org/resources/article/infographic-global-adequacy-capabilities/.

[7] “Action Plan for the Global Privacy Enforcement Network (GPEN),” https://www.privacyenforcement.net/content/home-public.

[8] “APEC Cross-border Privacy Enforcement Arrangement (CPEA),” Asian-Pacific Economic Cooperation, https://www.apec.org/Groups/Committee-on-Trade-and-Investment/Electronic-Commerce-Steering-Group/Cross-border-Privacy-Enforcement-Arrangement.aspx.

[9] For example: Federal Trade Commission, International Competition and Consumer Protection Cooperation Agreements, https://www.ftc.gov/policy/international/international-cooperation-agreements.

[10] Andrew Mitchell and Theodore Samlidis, “Cloud services and government digital sovereignty in Australia and beyond,” International Journal of Law and Information Technology, Volume 29, Issue 4, Winter 2021, Pages 364–394, https://doi.org/10.1093/ijlit/eaac003.

[11] Daniel Castro, “The False Promise of Data Nationalism” (ITIF, December 2013), http://www2.itif.org/2013-false-promise-data-nationalism.pdf.

[12] The hack on the U.S. Office of Management and Budget occurred, at least in part, in an on-premise environment as a result of compromised user credentials. While the AWS report does not specify that it was referring to the OPM hack, it is more than likely the example it refers to. It’s fairly clear from the agency OIG reports that OPM was running a number of their own data centers and they were behind on security. Min Hyun, “Addressing Data Residency with AWS,” AWS Blog post, February, 2018, https://aws.amazon.com/blogs/security/addressing-data-residency-with-aws/; The Majority Staff Report, “The OPM Data Breach: How the Government Jeopardized Our National Security for More than a Generation” (Committee on Oversight and Government Reform U.S. House of Representatives 114th Congress, September 7, 2016), https://republicans-oversight.house.gov/report/opm-data-breach-government-jeopardized-national-security-generation/;

[13] The Security and Exchange Board of India, “Advisory for Financial Sector Organizations regarding Software as a Service (SaaS) based solutions,” November 3, 2020, https://www.sebi.gov.in/legal/circulars/nov-2020/advisory-for-financial-sector-organizations-regarding-software-as-a-service-saas-based-solutions_48081.html.

[14] Daniel Castro and Alan McQuinn, “Unlocking Encryption: Information Security and the Rule of Law” (ITIF, March 2016), http://www2.itif.org/2016-unlocking-encryption.pdf.

[15] German Chancellor Angela Merkel saying that the EU should claim digital sovereignty by developing its own platforms to manage data in order to reduce its reliance on U.S. provider is simply a call for protectionist-based import substitution in the digital era. Guy Chazan, “Angela Merkel urges EU to seize control of data from US tech titans,” Financial Times, November 12, 2019, https://www.ft.com/content/956ccaa6-0537-11ea-9afa-d9e2401fa7ca; French President Emmanuel Macron is blunt: “The battle we’re fighting is one of sovereignty.” Charlene Barshefsky, “EU digital protectionism risks damaging ties with the US,” Financial Times, August 2, 2020, https://www.ft.com/content/9edea4f5-5f34-4e17-89cd-f9b9ba698103.

[16] Javier Espinoza and Guy Chazan, “Germany calls on EU to tighten grip on Big Tech,” Financial Times, November 11, 2019, https://www.ft.com/content/2d538f22-048d-11ea-a984-fbbacad9e7dd.

[17] Eline Chivot, “EU Data Strategy Has Worthwhile Goal, But Misses the Mark,” Center for Data Innovation blog post, August 13, 2020, https://datainnovation.org/2020/08/eu-data-strategy-has-worthwhile-goal-but-misses-the-mark/.

[18] Nigel Cory, “Response to the public consultation for the European Commission’s white paper on a European approach to artificial intelligence” (ITIF, June 12, 2020), http://www2.itif.org/2020-eu-approach-ai.pdf?_ga=2.86726097.873378596.1596032106-254668983.1577993982.

[19] “Australian Privacy Principles,” https://www.oaic.gov.au/privacy/australian-privacy-principles/read-the-australian-privacy-principles.

[20] “APEC Privacy Framework,” https://www.apec.org/docs/default-source/Publications/2017/8/APEC-Privacy-Framework-(2015)/217_ECSG_2015-APEC-Privacy-Framework.pdf.

[21] Chinchih Chen, Carl Benedikt Frey, and Giorgio Presidente, “Privacy Regulation and Firm Performance: Estimating the GDPR Effect Globally” (Working Paper No. 2022-1, University of Oxford), https://www.oxfordmartin.ox.ac.uk/downloads/Privacy-Regulation-and-Firm-Performance-Giorgio-WP-Upload-2022-1.pdf.

[22] Eline Chivot and Daniel Castro, “What the Evidence Shows About the Impact of the GDPR After One Year,” Center for Data Innovation, June 17, 2019, https://datainnovation.org/2019/06/what-the-evidence-shows-about-the-impact-of-the-gdpr-after-one-year/; Benjamin Mueller, “A New Study Lays Bare the Cost of the GDPR to Europe’s Economy: Will the AI Act Repeat History?,” Center for Data Innovation, April 9, 2022, https://datainnovation.org/2022/04/a-new-study-lays-bare-the-cost-of-the-gdpr-to-europes-economy-will-the-ai-act-repeat-history/.

[23]. Alan McQuinn and Daniel Castro, “The Costs of an Unnecessarily Stringent Federal Data Privacy Law” (ITIF, August 2019), https://itif.org/sites/default/files/2019-cost-data-privacy-law.pdf.

[24]. Ibid., 2.

[25] Schrems v. Data Protection Commissioner 2015, para 94.

[26] Nicholas Blackmore, "Feeling inadequate? Why adequacy decisions are rare (and may get rarer) in Asia-Pacific," Kennedys Law, March 26, 2019, https://www.kennedyslaw.com/thought-leadership/article/feeling-inadequate-why-adequacy-decisions-are-rare-and-may-get-rarer-in-asia-pacific

[27] For example, a report for the European Parliament on data protection in China states that there is “no common ground… found between two fundamentally different systems both in their wording and in their raison d’etre.” The report takes a relativist approach by saying China’s culture and approach to human rights means the European Union should treat China differently when it comes to trade and privacy issues, despite the fact that “China does not have a general data protection act but traces of data protection may be found in a multitude of sector-specific legal instruments.” Paul de Hert and Vagelis Papakonstantinou, “The Data Protection Regime in China” (Brussels: report for the European Parliament’s Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs, October 2015), http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/IDAN/2015/536472/IPOL_IDA(2015)536472_EN.pdf.

[28] Official Journal of the European Union, "Free Trade Agreement Between the European Union and the Republic of Singapore," November 14, 2019, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:22019A1114(01)&from=EN#page=28.

[29] Official Journal of the European Union, "Free Trade Agreement Between the European Union and the Republic of Singapore," November 14, 2019, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:22019A1114(01)&from=EN#page=28

[30] Such as: to notify data subjects of a wide range of information when collecting their personal data, including, for example, the existence of automated decision-making or profiling; to provide an individual a copy of their personal data in a "portable" format that they can take to another service provider; to notify data breaches to a supervisory authority and to affected individuals; and to appoint a data protection officer.

[31] David M. Halbfinger, Isabel Kershner and Ronen Bergman, "To Track Coronavirus, Israel Moves to Tap Secret Trove of Cellphone Data," The New York Times, March 16, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/16/world/middleeast/israel-coronavirus-cellphone-tracking.html.

[32] EU Scream Podcast, "Věra Jourová on surveillance and Covid-19," EU Observer, March 29, 2020, https://euobserver.com/eu-scream/147926; Kim Lyons, "Governments around the world are increasingly using location data to manage the coronavirus," The Verge, March 23, 2020, https://www.theverge.com/2020/3/23/21190700/eu-mobile-carriers-customer-data-coronavirus-south-korea-taiwan-privacy.

[33] Nigel Cory, Robert D. Atkinson, and Daniel Castro, "Principles and Policies for “Data Free Flow With Trust” (ITIF, May 27, 2019), https://itif.org/publications/2019/05/27/principles-and-policies-data-free-flow-trust. See also Robert Atkinson, “Don’t Just Fix Safe Harbor, Fix the Data Protection Regulation,” EurActiv, December 18, 2015, https://www.euractiv.com/section/digital/opinion/don-t-just-fix-safe-harbour-fix-the-data-protection-regulation/.

[34] Center for Information Policy Leadership (CIPL), "Cross-Border Data Transfer Mechanisms" (CIPL, August 2015), https://www.informationpolicycentre.com/uploads/5/7/1/0/57104281/cross-border_data_transfers_mechanisms_cipl_white_paper.pdf.

[35] Case 311/18 Data Protection Commissioner v Facebook Ireland Limited, Maximillian Schrems with others [2019] EU:C:2019:1145, Opinion of AG Saugmandsgaard Øe, para 108.

[36] European Parliament, "Report on the US NSA surveillance programme, surveillance bodies in various Member States and their impact on EU citizens’ fundamental rights and on transatlantic cooperation in Justice and Home Affairs" (European Parliament, February 21, 2014), https://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?type=REPORT&mode=XML&reference=A7-2014-0139&language=EN; European Parliament, "Q&A on Parliament's inquiry into mass surveillance of EU citizens - What do MEPs say about mass surveillance allegations in EU countries?" (European Parliament, March 10, 2014), https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20140310BKG38512/q-a-on-parliament-s-inquiry-into-mass-surveillance-of-eu-citizens/1/what-do-meps-say-about-mass-surveillance-allegations-in-eu-countries

[37] Peter Swire, "Working Paper - The USA Freedom Act: A Partial Response to European Concerns about NSA Surveillance" (Jean Monnet Centre of Excellence, Center for European and Transatlantic Studies (CETS) of Georgia Tech, and Sam Nunn School of International Affairs, 2015), https://inta.gatech.edu/sites/default/files/attachments/GTJMCE2015-1-Swire.pdf.

[38] Library of Congress, "Foreign Intelligence Gathering Laws: European Union" (last updated on September 27, 2016), https://www.loc.gov/law/help/intelligence-activities/europeanunion.php

[39] Directorate General for Internal Policies, Policy Department for Citizens' Rights and Constitutional Affairs, "The data protection regime in China - In-depth Analysis for the LIBE Committee" (European Parliament, 2015), https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/IDAN/2015/536472/IPOL_IDA(2015)536472_EN.pdf.

[40] “Government access to data in third countries,” European Data Protection Board, 2019, https://edpb.europa.eu/system/files/2022-01/legalstudy_on_government_access_0.pdf.

[41] European Commission, "Commission welcomes European Parliament's approval of EU-Vietnam trade and investment agreements," Press Corner, February 12, 2020, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_20_227.

[42] “European Parliament resolution of 15 November 2018 on Vietnam, notably the situation of political prisoners,” November 15, 2018, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-8-2018-0459_EN.html.

[43] Delegation of the European Union to Vietnam, "Guide to the EU-Vietnam Trade and Investment Agreements" (updated in March 2019), https://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2016/june/tradoc_154622.pdf.

[44] See section 3.2.2.2 in Sandra Wilderoth, "EU data transfer requirements for an adequacy decision and the Vietnamese legal realities" (Lund University, Faculty of Law, 2019), http://lup.lub.lu.se/luur/download?func=downloadFile&recordOId=9000444&fileOId=9003963; Vietnam’s Constitution, art. 14-15.

[45] Sandra Wilderoth, "EU data transfer requirements for an adequacy decision and the Vietnamese legal realities" (Lund University, Faculty of Law, 2019), http://lup.lub.lu.se/luur/download?func=downloadFile&recordOId=9000444&fileOId=9003963.

[46] See for instance LCIS, art 20(2) which provides that state agencies shall, annually or when necessary, inspect and examine personal information-processing organizations and individuals which can be assumed to involve access to personal data; LIT, arts 18(3)(a).

[47] CSL, art 1.

[48] Federal Trade Commission, “FTC Approves Final Orders Resolving Allegations That Companies Misrepresented Participation in International Privacy Program” (U.S. Federal Trade Commission, April 14, 2017), https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2017/04/ftc-approves-final-orders-resolving-allegations-companies?utm_source=govdelivery (accessed March 21, 2019).

[49] Information Integrity Solutions, “Towards a Truly Global Framework for Personal Information Transfers - Comparison and Assessment of EU BCR and APEC CBPR Systems," (September 2013), https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5746cdb3f699bb4f603243c8/t/575f628a8a65e232a6959b80/1465868951114/IIS+CBPR-BCR+report+FINAL.pdf.

[50] Alex Wall, “GDPR matchup: The APEC Privacy Framework and Cross-Border Privacy Rules,” IAPP, May 31, 2017, https://iapp.org/news/a/gdpr-matchup-the-apec-privacy-framework-and-cross-border-privacy-rules/; Information Integrity Solutions, Towards a Truly Global Framework for Personal Information Transfers - Comparison and Assessment of EU BCR and APEC CBPR Systems" (September 2013), Information Integrity Solutions, Towards a Truly Global Framework for Personal Information Transfers - Comparison and Assessment of EU BCR and APEC CBPR Systems" (September 2013), https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5746cdb3f699bb4f603243c8/t/575f628a8a65e232a6959b80/1465868951114/IIS+CBPR-BCR+report+FINAL.pdf.

[51] Information Integrity Solutions, “Towards a Truly Global Framework for Personal Information Transfers - Comparison and Assessment of EU BCR and APEC CBPR Systems," (September 2013), https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5746cdb3f699bb4f603243c8/t/575f628a8a65e232a6959b80/1465868951114/IIS+CBPR-BCR+report+FINAL.pdf.

[52] Ibid.

[53] Ibid.

[54] Ibid.

[55] Article 29 Data Protection Working Party, Opinion 02/2014 on a referential for requirements for Binding Corporate Rules submitted to national Data Protection Authorities in the EU and Cross Border Privacy Rules submitted to APEC CBPR Accountability Agents (27 February 2014); Information Integrity Solutions, "Success Through Stewardship: Best Practice in Cross-Border Data Flows," (January 23, 2015), https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5746cdb3f699bb4f603243c8/t/575f639a01dbaeed2ba40cd0/1465869227869/IIS_Success_through_stewardship_Best_practice_in_cross_border_data_flows.pdf.

Related

February 27, 2025