Comments to USTR Regarding the Trade Agreement Between the United States, Mexico, and Canada

Contents

The United States Should Support USMCA’s Renewal 2

Shielding USMCA From Chinese Mercantilism. 7

Improve the USMCA Competitiveness Committee 8

A New USMCA Should Provide the Template for Modern Digital Trade Agreements 9

Reinforce the USMCA to Protect U.S. Intellectual Property Rights 13

What USMCA Partners Should Not Do. 14

Introduction

The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) is pleased to submit the following comments for consideration by the Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR) for the joint review (Joint Review) of the Agreement between the United States of America, the United Mexican States, and Canada (USMCA). ITIF is an independent, nonprofit, nonpartisan research and educational institute focusing on the intersection of technological innovation and public policy.

ITIF urges the U.S. government to renew the USMCA. The USMCA strengthens America’s position to compete with China. First, it enables U.S. manufacturers to source inputs from Canada and Mexico at lower cost, as USMCA-qualifying goods—those meeting the agreement’s rules-of-origin (ROO) thresholds—move tariff-free across the region. Second, it helps weaken China’s manufacturing capacity by incentivizing firms to reshore production to North America and substitute Chinese imports with inputs or final products made within the region. The renewal of the USMCA should be conditioned on Mexico’s full compliance with its intellectual property (IP) commitments under the current agreement.

USMCA renewal should reflect a modernized version of the existing agreement. First, the new agreement needs concrete rules to shield the USMCA regional economy from Chinese predatory practices, including strengthening rules of origin rules and enforcement, implementing more commonly standardized investment screening practices, and allowing mechanisms to exclude IP mass infringers from the North American economy. Second, USMCA countries should jointly establish common goals to improve the region’s competitiveness. Third, the current digital trade chapter should be modernized to include provisions on adopting emerging technologies and facilitating digital governance—for example, e-payments—and to address topics that currently define the North American digital economy, such as hardware and export controls. Fourth, the agreement should continue to strengthen the rules underpinning IP rights throughout the region, particularly in the life sciences. This submission also incorporates suggestions on what USMCA countries should not do to compromise or undermine the USMCA: misleadingly promote “digital sovereignty” principles and expand tariff escalation to USMCA-qualifying goods. Lastly, if the United States is to take the USMCA seriously, it must advocate for and itself embrace a tariff-free trading environment in North America.

The United States Should Support USMCA’s Renewal

The U.S. government should take the lead and urge Canada and Mexico to continue the USMCA. According to its original text, if the 2026 review of the agreement leads to renewal, USMCA shall continue in force for 16 years, with a review in 2032. Alongside renewing the USMCA, the U.S. government should consider starting negotiations to expand the USMCA to other economies in the Americas that can complement U.S. capabilities. Key candidates include existing bilateral free trade partners—Chile, Colombia, Panama, and Peru—as well as countries in the Dominican Republic-Central America FTA (CAFTA-DR) with high-tech production capabilities (especially Costa Rica and the Dominican Republic).

The Case for a North American Production System

The United States should make the development of a competitive North American Production System—a “factory North America”—the top priority. A stronger North American production system enhances U.S. techno-economic power by expanding regional manufacturing capacity and reducing dependence on China through reshoring and shifting trade flows from it.

The three neighbors should work together to proactively support a North American production system, as investments, research and development (R&D), and trade among these countries are more likely to benefit others in North America than production networks based in China. However, for this to happen, especially in manufactured and advanced technology products, the United States needs to stop including Mexico and Canada in discriminatory domestic requirements (such as with steel tariffs and Buy American provisions).

The United States also needs to stop reflexively opposing U.S. firms that move or increase production in Mexico. That’s because production in Mexico is fundamentally different from that in China. For example, 40 percent of the inputs to finished manufactured goods in Mexico come from the United States.[1] By contrast, for China, that figure is a mere 4 percent. In essence, unlike trade with Mexico (and Canada), when production goes to China, the United States loses out on much more of the production process and interlinkages, not to mention enabling a potent adversary.

Indeed, one of the greatest strengths of NAFTA (the North American Free Trade Agreement, the preceding trilateral agreement) and USMCA has been the creation of continentally integrated markets and production networks, particularly for sectors such as autos, where parts and components may cross the borders of North American countries as many as eight times before being installed in a final assembly plant.[2] Similarly, medical devices cross North American borders many times as they are refined toward final production.[3]

The USMCA strengthens North America’s ability to leverage its complementary supply chain advantages. For example, while the United States depends on Mexico for a lower-cost production environment, Mexican firms source many inputs from U.S. firms, as evidenced by robust intra-industry trade surpluses. For example, a 2019 ITIF report found that, in trade with Mexico, tech-based industries accounted for 42 percent of gross exports and 56 percent of gross imports, and 45 percent of value-added exports and 49 percent of value-added imports.[4] These figures show that exports to Mexico are more tech-based and imports are less tech-based (i.e., complex and R&D-intensive) than gross values suggest. In general, trade with Mexico is less tech-based, but the United States relies on Mexican production facilities in large part to supply consumers with cheap tech-based products.

Canada complements the United States’ lead role in knowledge-intensive and value-added manufacturing. However, looking ahead, Canada can specialize in the mining and processing of the critical minerals needed in many advanced technologies, such as electric vehicles (EVs). Canada also brings distinct strengths in the aerospace, quantum, and ICT services sectors, and Mexico is growing in sectors such as ICT manufacturing and services and automotive supply.

USMCA Is a Building Block of the United States’ Techno-Economic Power

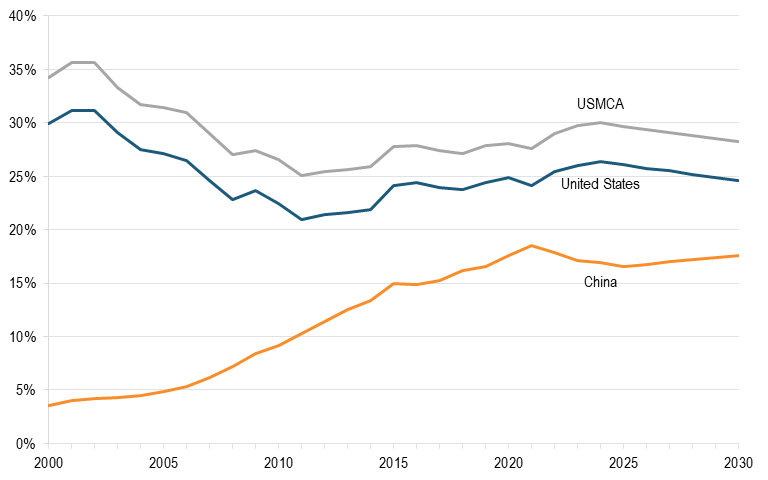

The United States is much better positioned to compete globally against China if the USMCA is treated as a single economic bloc. Indeed, the United States needs to promote a “Factory North America” if it—and the region—is to effectively compete with China. Figure 1 shows the relative size of the economies of China, the United States, and the USMCA compared to the global economy since 2000. While the United States experienced a relative decline during the first two decades of the century, China has rapidly expanded its global economic influence, growing from less than 3 percent of the global economy in 2000 to over 17 percent in 2020. By the end of the decade, China is projected to close the gap in its share of the global economy with the United States to just 2.5 percentage points. Policymakers need to acknowledge that the United States is in an industrial war against the People’s Republic of China (PRC)—and America is not winning.[5]

Figure 1: Gross domestic product as a share of the total global (estimates for 2025–2030)[6]

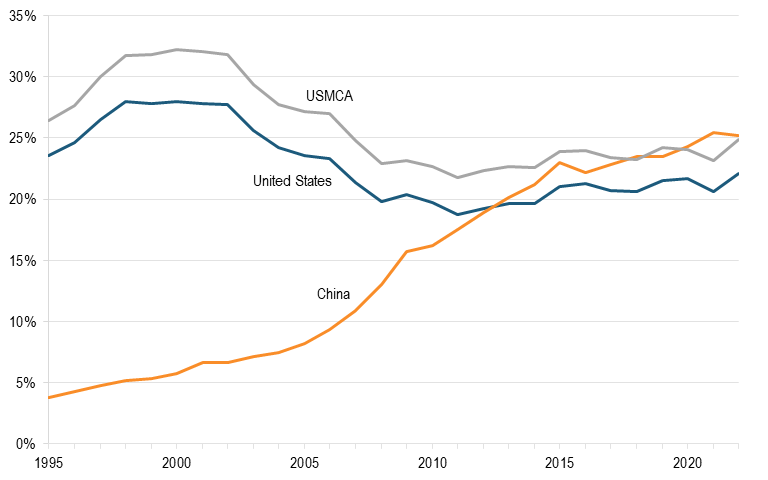

China has already surpassed the United States in production in many strategic sectors, but the gap is much narrower considering the USMCA economic bloc. To measure how economies’ manufacturing capacity in strategic sectors has evolved relative to one another, ITIF created the Hamilton Index.[7] The index measures changes in countries’ global share of value-added output across 10 advanced-industry sectors: pharmaceuticals; electrical equipment; machinery and equipment; motor vehicle equipment; other transport equipment; computer, electronic, and optical products; information technology and information services; chemicals (not including pharmaceuticals); basic metals; and fabricated metals.[8] The sectors covered in the Hamilton Index together accounted for nearly $12 trillion in global production in 2022—the last year with available data—representing over 11 percent of the world’s economy. Figure 2 summarizes China’s, the United States’s, and the USMCA countries’ share of output in Hamilton industries from 1995 to 2022. China’s global share of output in these industries has quintupled over that timeframe, rising to 22 percent, 3.1 percent higher than the U.S. share—however, counting USMCA, this gap is reduced to only 0.3 percentage points.

Figure 2: Historical shares of global output in Hamilton industries (1995–2022)[9]

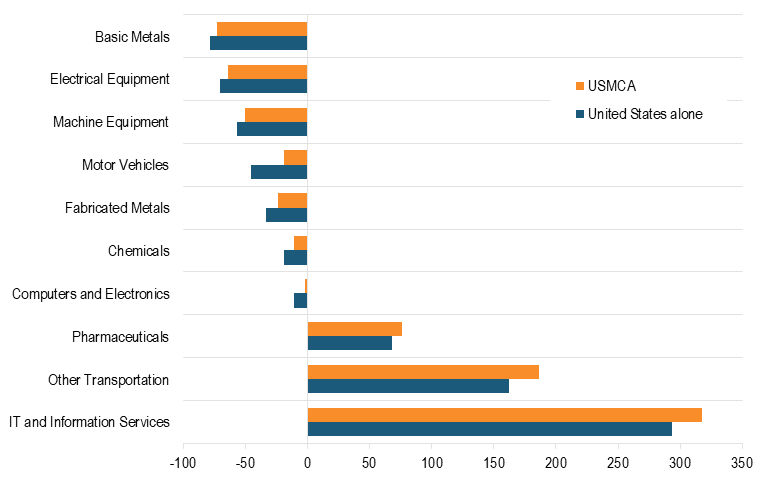

At the sectoral level, the USMCA’s economic bloc can help narrow the gap with China’s output in strategic industries (or expand it) by at least six percentage points. Figure 3 shows the differences between China’s output by sector and the United States, and between the USMCA’s economic bloc and the United States. Canada and Mexico, on average across sectors, represent 6 percent of Chinese production in strategic industries. There are three sectors in which the contribution of these two economies exceeds 24 percent of China’s output: motor vehicles, other transportation, and IT and information services. In contrast, China’s output in 7 of 10 strategic sectors exceeds that of the United States or the USMCA economic bloc—the North American economies lead only in pharmaceuticals, other transportation, and IT and information services.

Figure 3: How the USMCA economic bloc closes the gap with China in Hamilton industries (percentage points of difference in output)[10]

Case Studies: USMCA Bolstering U.S. Competitiveness in Strategic Industries

This section provides examples of how the USMCA is benefiting American companies competing in Hamilton industries. U.S. companies benefit from the certainty provided by USMCA, which ensures that USMCA-qualifying products won’t be subject to tariffs—and from the overarching rules-based stability it provides, ensuring fair and non-discriminatory competition. Beyond these cases, it’s worth noting that the uncertainty around USMCA renewal is itself curtailing investment that could further benefit U.S. companies.[11]

Semiconductors: Micron Technology’s Cross-Border Expansion

Micron Technologies, an American semiconductor company based in Idaho, has leveraged USMCA’s efficiency gains to develop a more resilient supply chain. For example, in 2024, it announced a new semiconductor assembly and R&D center in Guadalajara, Mexico, to complement its U.S. operations and reduce its reliance on China.[12] Timely, this investment has helped the company remain resilient against Chinese predatory practices, as Micron reportedly exited the server chip market in China in October 2025 following a Chinese government ban.[13]

Automobiles: Engine of Ford’s Flagship Vehicle Ping-Pongs the Border

The 5.0-liter V8 engines of the Ford F-150 and Ford Mustang are produced in Ontario, Canada, while the final product requires crossing the U.S.-Canada border “five or six times.”[14] The Ford F-150 has been the most popular vehicle sold in the United States for over four decades. It is assembled in Michigan or Missouri, with nearly 45 percent of its parts coming from Canada or the United States, and a significant share of the remainder manufactured in Mexico.[15]

Shielding USMCA From Chinese Mercantilism

Reinforce FDI Screening and Information-Sharing Mechanisms

Chapter 14 of the USCMA addresses investments, but it needs to be reformed to establish coordination mechanisms to prevent Chinese investment in strategic industries. ITIF has recently reported how Chinese electric vehicle makers have benefited from aggressive state-sponsored mercantilist policies and explained why they should not be allowed to manufacture in the United States.[16] The USMCA should create mechanisms that allow the United States to coordinate the screening of foreign direct investment (FDI) in North America, providing it with the tools to identify and potentially ban predatory investments in the region and to prevent products such as Chinese EVs from entering the U.S. market. In addition, a reformed Chapter 14 should outline mechanisms to share information on foreign investment screening from “countries of concern,” with clear objectives, responsibilities, and a mandate to report to the three partners.

Tighten Regulations on Rules of Origin

Rules of Origin (ROOs) define where a product is made, which is not always straightforward. The U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) considers a product made in a certain country if its inputs undergo a “substantial transformation”—a definition heavily contested. For example, CBP issues over 50 ROO rulings annually just for Canada and Mexico.[17] By improving ROO standards under the USMCA, the United States can prevent Chinese inputs from entering Canada and Mexico’s supply chains and the final products derived from them from entering the U.S. market unwantedly.

USMCA-qualifying products are defined by regional content production, not by a firm’s nationality. Thus, a Chinese company investing in North America is treated the same as any other and is given potential tariff-free access to the U.S. market. This ignores the mercantilist nature of the Chinese economy—any company competing against Chinese peers faces potentially significant disadvantages, since the latter often receive numerous forms of support from China’s innovation mercantilist strategy (e.g., massive subsidies, extensive IP theft, barriers to Chinese firms competing in China’s market, etc.) While the United States has tools to prevent the entry of Chinese products benefitting from mercantilist practices—such as antidumping, countervailing duties, targeted tariffs, or market exclusion (e.g. if a product were found to be infringing a U.S. owner’s IP rights in a Section 337 case), the USMCA itself should contain rules that help prevent Chinese companies benefitting from mercantilist policies from getting their final products (or even inputs) into the U.S. market.

The USMCA should raise thresholds for what is considered locally produced in the region to qualify as a USMCA product if the production is derived from Chinese FDI. The current USMCA ROOs define thresholds based on what is produced within North America (i.e., regional value content, or RVC). USMCA’s ROO thresholds vary by product and industry, and any potential change to the rule should be analyzed on a case-by-case basis. However, USMCA’s ROOs are neutral regarding the firm’s ownership. A renewed USMCA should include additional thresholds for products manufactured in North America by Chinese-owned companies.

In addition, there are reports that the enforcement of ROOs needs improvement.[18] ROO enforcement can be improved by expanding oversight funding and implementing real-time verification of supply chain data and regional content. This would require an explicit and binding commitment from all trade partners.

USMCA Partners Should Refrain From Entering Into Unilateral Trade Arrangements With China

Canada and Mexico should not negotiate trade deals with China unilaterally. The current USMCA (article 32.10) includes a clause that allows countries to terminate the agreement if another party signs a free trade agreement (FTA) with a non-market country, including China. This safeguard should cover all trade deals and arrangements, not just full FTAs, to prevent USMCA partners from entering into any trade arrangement with a non-market country—particularly China—without prior consultation and alignment with the other partners. Revising this clause would prevent, for example, Canada’s reported consideration of lifting its 100 percent tariffs on Chinese EVs, which could undermine North America’s auto industry.[19]

Incorporate Provisions to Exclude Intellectual Property Mass Infringers From the North American Economy

The Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) chapter of a renewed USMCA should include commitments that USMCA members update their domestic legislation to exclude companies from countries of concern that are frequent or blatant IPR infringers from their markets. ITIF has proposed that USTR support ongoing discussions in Congress about amending the Tariff Act of 1930 to enable stronger use of the U.S. International Trade Commission’s (USITC) Section 337 statute to make it easier to exclude goods and services from China supported by systemically unfair trade practices.[20] Section 337 allows the U.S. International Trade Commission to investigate foreign companies’ unfair trade practices, often involving IP infringement and antitrust violations, to impose remedies such as banning infringing products from entering the U.S. market. This legislation was designed to address and enforce laws against infringing companies, imposing restrictions on specific goods. However, legislators did not consider that an entire national economy could be an infringer, making the tool insufficient and outdated. Further, Section 337 does not address other unfair predatory practices widely used by the Chinese government, such as forced technology transfers, closed domestic markets, massive industrial subsidies, or soft loans.

Support United States “Plus” Canada and Mexico, as Opposed to a U.S.-Only Strategy

U.S. policymakers need to differentiate between the significant economic benefits the U.S. economy derives from U.S. firms setting up operations in Mexico (and Canada) versus China. U.S. firms depend on global operations in places like Mexico to remain competitive, and often the choice is not between the United States and Mexico as production locations, but between Mexico and China.[21] In addition, a strategy of reshoring production from China to Mexico can help the United States weaken the Chinese manufacturing economy, while helping America’s, as spillovers and agglomeration effects can benefit U.S. manufacturing.

Improve the USMCA Competitiveness Committee

The current Competitiveness chapter (chapter 26) establishes the USMCA Competitiveness Committee (the Committee).[22] However, the objectives of this Committee are not narrowly defined, and practically any aspect of the North American economy falls within its scope. The Committee should explicitly seek to boost the competitiveness of the region’s strategic industries. To do so, it should include:

▪ Explicit definitions of its members and annual goals. A renewed USMCA should explicitly designate one agency per country responsible for competitiveness and productivity, with the head serving as the representative on the Committee. The agreement should also explicitly require the Committee to focus on strategic sectors—three at a time—narrowing the action plan to develop coordination mechanisms, metrics and joint analytics, and measurable objectives to improve the competitiveness of these sectors within three years. The first sectors to target should be autos, information and communication technologies (ICT), and base metals and critical minerals.

▪ Improve and standardize how USMCA members collect, share, and publish competitiveness data. The Committee should proactively publish updated information on trade and investment facilitated by USMCA rules. The Committee should also identify important sub-national metrics that are not currently collected or shared publicly among USMCA partners, and collaborate with each country and region to develop these indicators.[23] For example, policymakers would benefit from detailed firm-level information on the use of USMCA products as intermediate goods, the intensity of highly qualified personnel, cross-border research efforts, and the adoption and absorption of digital technologies.

▪ The Committee should jointly develop annual recommendations for each party to improve competitiveness. In other words, the Committee should, each year, prepare a brief policy document for each country that contains recommendations to improve the three countries’ competitiveness. These recommendations should be publicly available, contain measurable objectives, and each year’s report should account for which previous recommendations were considered.

▪ Develop a North American manufacturing digitalization strategy and ecosystem. USMCA partners should launch a coordinated strategy to accelerate the digital transformation of North American manufacturing. A jointly funded initiative should support the creation of a regional digital-manufacturing ecosystem, with companion institutes in Canada and Mexico linked through formal cooperation channels. Alternatively, the governments could sign a memorandum of understanding allowing Canadian and Mexican firms and agencies to co-fund and participate in projects at the U.S. Digital Manufacturing and Cybersecurity Institute (MxD), one of the 18 innovation institutes in the Manufacturing USA network. This collaboration would foster a cross-border innovation hub to share tools, software, standards, and workforce skills (particularly for small and medium enterprises) and scale the adoption of advanced digital manufacturing production technologies across the region.

A New USMCA Should Provide the Template for Modern Digital Trade Agreements

The USMCA was a pioneering agreement toward advancing digital trade rules worldwide. At the time the agreement entered force in 2020, it contained the strongest commitments on digital trade rules of any international agreement. The USMCA’s robust digital rules remain in place; however, after five years, other countries have signed agreements related to the digital economy with novel approaches.[24] (See appendices.) U.S. policymakers should review these to identify new approaches to help keep the USMCA amongst the world’s leading digital-trade-promoting agreements.

U.S. leadership in setting digital trade rules matters for several reasons. First, it safeguards America’s position at the forefront of the global digital economy. U.S. technology companies depend on open cross-border data flows, bans on data-localization mandates, protections for source code, and strong cybersecurity standards to scale internationally. These rules enable digital services companies to aggregate data, refine services, and stay globally competitive.[25] Second, they prevent other jurisdictions from imposing discriminatory measures that undermine innovation. The European Union’s Digital Markets Act (DMA) designates so-called “gatekeepers,” a group of seven digital companies—of which five are American—selected based on revenue, market capitalization, and user base thresholds.[26] The DMA’s rules degrade users’ experiences due to anti-self-preferencing rules, decrease privacy and security by mandating interoperability, and adopt a “precautionary principle” approach that undermines innovation.[27] Europe has promoted its restrictive approach to digital markets regulation globally, trying to get other countries to implement DMA-like rules, in a phenomenon known as the “Brussels effect.” North American policymakers should explicitly reject this approach, and recognize that by operating under predictable, pro-innovation digital trade frameworks, U.S. tech firms can reinvest efficiency gains from global scale into research and development—fueling the next wave of technological leadership.[28]

Third, the United States can gain a relative advantage in its strategic competition by leading in setting global digital trade rules. The underlying principles that set these rules reflect countries’ technological trajectories and priorities, and the expansion of these rules eases the adoption of these technologies worldwide. China aligns digital trade with principles that enable it to surveil its population in a relatively unrestricted manner and to set digital rules that facilitate the adoption of Chinese technologies overseas.[29] The differences between the U.S. and Chinese approaches are clear, such as in data localization rules—meaning, companies being forced to keep data within a country. Chinese firms can gain a competitive advantage from data localization because they are willing to comply with surveillance and censorship requests from foreign governments. In contrast, U.S. companies focus on efficiency and benefit from regional data centers, facilitated by cross-border data flows, that serve multiple markets.[30]

These differences are reflected in how China shapes digital trade rules. China is leading trade initiatives in the Indo-Pacific, notably as a proponent of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). RCEP makes cross-border rules compatible with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) digital laws (e.g., Cybersecurity, Data Security, and Personal Information Protection Laws), permitting data localization rules under “essential security interests” excuses.[31]

The United States should push for a modernization of the USMCA’s digital trade chapter with a clear focus on strengthening the competitiveness of American firms and enhancing regional digital governance. Updating the agreement would reinforce transparent, nondiscriminatory rules that preserve the scale and efficiency advantages of U.S. technology companies across the North America region. More detailed and flexible provisions on data governance, cybersecurity, and the responsible use of AI in government procurement would create a more predictable and innovation-friendly environment for U.S. cloud, software, and AI providers—crucial to the administration’s objective of exporting an American AI technology stack.[32] These changes would also bring Canada and Mexico closer into alignment with the U.S. vision for open, interoperable, and market-driven digital rules—helping curb the proliferation of restrictive “digital sovereignty” frameworks.

▪ The digital trade chapter should become a “digital economy and security chapter.” The nominal change should reflect a shift in understanding of what this chapter covers, modernizing it for the current era, as the global trade system is experiencing the most significant change since the post-war era. The chapter should cover all digital topics, including infrastructure and hardware, and include provisions and sanctions that ban the presence of adversaries in the North American telecommunications network (Huawei, for example, is widely used in Mexico).[33] The reframing from “trade” to “economy” should be understood as allowing the chapter to be part of the “DTA+” type of agreement, covering emerging topics such as AI.[34] Finally, including the security angle would allow U.S. policymakers to include export control alignment provisions, which are currently absent from the USMCA.

▪ Add provisions for pro-innovation emerging technology adoption rules. ITIF suggests considering the DEPA text as a template for the following topics:[35]

– E-invoicing:

“Each party shall ensure that the implementation of measures related to e-invoicing in its jurisdiction is designed to support cross-border interoperability. For that purpose, each party shall base its measures related to e-invoicing on international standards, guidelines, or recommendations, where they exist.”

– E-payment:

“Parties agree to support the development of efficient, safe and secure cross-border electronic payments by fostering the adoption and use of internationally accepted standards, promoting interoperability and the interlinking of payment infrastructures, and encouraging useful innovation and competition in the payments ecosystem.”

“The Parties shall endeavour to take into account, for relevant payment systems, internationally accepted payment standards to enable greater interoperability between payment systems.”

“The Parties agree that policies should promote innovation and competition in a level playing field and recognise the importance of enabling the introduction of new financial and electronic payment products and services by incumbents and new entrants in a timely manner such as through adopting regulatory and industry sandboxes.”

– Digital ID:

“Each party shall endeavour to promote the interoperability between their respective regimes for digital identities. This may include (…) comparable protection of digital identities afforded by each party’s respective legal frameworks, or the recognition of their legal and regulatory effects, whether accorded autonomously or by mutual agreement.”

– Government Procurement:

“The Parties recognise that the digital economy will have an impact on government procurement and affirm the importance of open, fair and transparent government procurement markets.”

“To this end, the Parties shall undertake cooperation activities in relation to understanding how greater digitisation of procurement processes, and of goods and services impacts on existing and future international government procurement commitments.”

– Data innovation:

“The parties recognise that cross-border data flows and data sharing enable data-driven innovation. The parties further recognise that innovation may be enhanced within the context of regulatory data sandboxes where data, including personal information, is shared amongst businesses in accordance with the parties’ respective laws and regulations.”

▪ Incorporate provisions to avoid disproportionate and unfair policies targeting American companies. In recent years, there has been a proliferation of policies worldwide targeting U.S. technology companies (reported in the ITIF Big Tech Policy Tracker).[36] The USMCA fails to prevent these attacks on U.S. technology companies, mainly because the proliferation of policies targeting them occurred after the agreement entered into force. The causes of this proliferation are varied. For example, it is politically easier to capture rents from foreign companies than to implement a neutral and fair regulatory system. In addition, the U.S. government has made insufficient efforts to protect its companies overseas. A renewed USMCA should:

– Avoid carve-outs to existing digital trade provisions that allow USMCA members to implement rent-seeking policies targeting U.S. firms. For example, the current digital trade chapter excludes all government procurement policies from its provisions. This makes it easier for policymakers to include data localization requirements and weakens protections for source code, among other irritants.

– Include a provision explicitly banning digital service taxes (DST). Digital service taxes are levied on digitally delivered services, such as online marketplaces, advertising, social media platforms, and the sale of user data. DSTs typically impose taxes on the domestic revenue of multinational companies in a narrow range of business models, and include thresholds to exclude all but the largest firms.[37] DSTs represent a distortive tax that discriminates against a narrow set of companies and sectors, penalizes large companies, and unfairly punishes the same transactions depending on the platform on which they are made (e.g., an online purchase might be subject to the DST or not, based on whether the company meets the tax’s thresholds).[38]

– Avoid online liability provisions that would involve changes in Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act. Section 230 includes two main provisions: one that protects online services and users from liability when they do not remove third-party content, and one that protects them from liability when they do remove content.[39] This provision afforded legal protection to U.S. technology companies—allowing them to innovate, test new products and services, and maintain American leadership in the digital sector. Without this provision, online services would face substantial legal costs for third-party content, users and businesses would face higher costs for digitally delivered services, and some online services would risk shutting down or eliminating popular features.[40]

Reinforce the USMCA to Protect U.S. Intellectual Property Rights

The USMCA’s chapter 20 on intellectual property rights (IPRs) defines rules aligned with international standards, such as those defined by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). This chapter establishes provisions related to IPRs—for example, on patents, regulatory exclusivities, copyrights, trade secrets, trademarks, and industrial design—alongside enforcement mechanisms. USMCA’s IPR chapter represented a modernization of NAFTA’s by including, among other elements, a longer copyright term of life of the author plus 70 years, a mandate to provide patent term extension for unreasonable patent office delays, and a provision of full national treatment for copyright and related rights.[41]

USTR should urge its Canadian and Mexican counterparts to improve their policies and enforcement of IPR protections. Despite the updated framework, Canada and Mexico are recurring infringers of IPRs. Both countries are listed on USTR’s 2025 “Special 301 Report on Intellectual Property Protection and Enforcement” (the IP Watch List). Canada remains on this report due to poor enforcement of counterfeits at the border and allegations that pirated subscription services have been sold physically and online.

Mexico is listed on the Priority Watch List, among a group of countries with “onerous or egregious acts, policies, or practices and whose acts, policies, or practices have the greatest adverse impact (actual or potential) on the relevant U.S. products.”[42] The main reason for including Mexico on this list is its unresolved USMCA commitments—especially the lack of action in investigating and prosecuting trademark counterfeiting and copyright piracy, as well as the Attorney General’s failure to report IP enforcement statistics. Mexico also continues to provide weak protection of pharmaceutical IP and poor enforcement of IPRs online.[43]

Concerningly, Mexico has failed to meet its USMCA obligation to provide patent term extensions that compensate for unreasonable delays in patent approval.[44] The USMCA requires members to ensure that pharmaceutical patent holders receive the full effective term of protection, even when administrative processes shorten it. Mexico’s four-and-a-half-year transitional period to implement this measure expired on January 1, 2025. In September 2025, Mexico’s president Claudia Sheinbaum submitted a law to fulfill Mexico’s USMCA commitments on IPR protection, although this still awaits passage.[45] U.S. policymakers should condition the renewal of the USMCA on Mexico fulfilling its current commitments within the first six months of 2026.

Besides strengthening the enforcement of USMCA commitments, an updated IPR chapter should also include the following additions:

▪ Incorporate provisions protecting rightsholders from digital piracy by allowing modern, safe website blocking practices. Digital piracy represents a growing illegal business, costing American firms over $29 billion annually.[46] The most effective tool against digital piracy is allowing courts to issue injunctions to block piracy websites and their proxy sites—including foreign sites—as well as temporary blocks to protect live events.[47] The revised UMSCA should include a provision with these characteristics. Canada is the only USMCA country that has these mechanisms. Mexico allows for blocking piracy sites, but not its proxies or live events, and the United States does not allow blocking foreign piracy sites.

▪ Incorporate a provision establishing a minimum of 10 years of biologics data protection. A provision requiring regulatory data supporting new biologic drugs to be protected for at least 10 years was incorporated into the original USMCA text but later removed.[48] (House parliamentarians argued that it would increase the cost of medicines, yet without much supporting data.)[49] This was a mistake, and it needs to be amended.

This provision is needed due to the distinct character of innovating biologic drugs. While patents constitute one important form of IP protection for biologics, they are not sufficient to support the environment needed to promote large-scale investment in biologic R&D, for two principal reasons. First, because biologics are structurally complex molecules which are closely tied to a specific manufacturing process, many biologic patents are process patents or relatively narrowly constructed product patents. This means that biologics patents are susceptible to being circumvented by small changes to the molecule or to the process of making it.[50] Because patents fail to provide the same certainty for biologics as they do for traditional pharmaceutical drugs, they do not necessarily assure that biologics will enjoy the same length of time on the market before facing competition from generics. Second, patents do not safeguard the intellectual property involved in developing the extensive clinical trial data and results required to prove the safety and efficacy of a biopharmaceutical product (e.g., the regulatory data).

Recognizing the need to strike a balance between innovators’ incentives for investment in expensive and risky novel drug development while at the same time making room for competition by creating a path for biosimilar manufacturers to bring biosimilar products to market, the U.S. Congress enshrined in the bipartisan Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BCIPA) 12 years of data exclusivity protection for novel biologic medicines. This has helped unleash a flourishing of biologics innovation in the United States.

Today, biologic medicines account for 40 percent of drugs under development.[51] Accordingly, if North America is to be the premier location in the world for developing the next generation of drugs for the benefit of humankind, then the USMCA should commit participating nations to providing at least 10 years of data exclusivity protection for biologic drugs.

▪ USMCA partners should adopt a robust patent- and exclusivity-linkage regime for biologics and other medicines, requiring regulators to verify active exclusivities on the reference product before authorizing generic product entry. Implementation should include early notice to rightsholders, a transparent patent/exclusivity register, regulator–IP office coordination, and a time-limited pre-launch stay to resolve disputes. This framework provides innovators with predictable recovery of high-risk R&D, prevents costly at-risk launches for generics, and blocks disruptive post-launch switches for patients.[52]

What USMCA Partners Should Not Do

Misleadingly Promote “Digital Sovereignty” Principles

USMCA partners should steer clear of the trap of promoting so-called “digital sovereignty” principles without considering their costs, practicality, or even clarifying what they mean by this notion. Authorities from all USMCA countries have supported initiatives that advocate for digital sovereignty principles. This narrative is misleading (it doesn’t achieve self-sufficiency goals), inefficient (it raises costs by creating rules that impede technology companies’ ability to scale), and discriminatory (it favors local companies over foreign competitors).

For example, Canada’s Prime Minister, Mark Carney, announced in September 2025 that the Canadian government will support the development of a Canadian “sovereign cloud.”[53] His statement was framed as an attempt to “build compute capacity and data centers” to boost competitiveness, security, and independence, giving Canada an “independent control over advanced computing power.”[54] Under this framework, the government announced the Canadian Sovereign AI Compute Strategy, an agenda to attract private-sector investment, promote public digital infrastructure, and secure access to compute power, particularly for researchers.[55]

While perhaps well-intentioned, the “cloud sovereignty” efforts by Canadian authorities represent a mix of data localization rules and subsidies for Canadian domestic cloud providers. These measures limit the efficiency of computing power by restricting it to a local rather than a global scale and do not truly provide “sovereignty” as generally understood—namely, reducing dependence on foreign technologies. Canada’s digital infrastructure will still rely on chip design and manufacturing, telecommunications networks, and hardware and software produced outside the country.

Mexico has also embraced the rhetoric of “digital sovereignty.” In September 2025, president Sheinbaum announced the government’s goal of achieving “true technological independence” by 2045.[56] The accompanying strategy, however, primarily emphasizes capability building rather than isolation. The plan envisions that, by mid-century, Mexico will possess a “robust and redundant” digital infrastructure and emerge as a provider of open, interoperable, and transferable digital resources.[57] The government’s agenda centers on expanding Internet access, investing in digital infrastructure, deploying digital government services, and strengthening data protection frameworks. Similar to Canada’s approach, Mexico’s plan does not depend exclusively on domestic suppliers. Instead, it seeks to enhance national digital capabilities while maintaining engagement with global technology firms.

The U.S. government has also fallen into this narrative. White House Technology Advisor Michael Kratsios announced in August 2025, during a multilateral meeting, that the United States wants trade partners to have “AI sovereignty, data privacy, and technical customization.”[58] Differing from Canada and Mexico’s cases, Kratsios was referring to “AI sovereignty as the ability of a nation to dictate the terms on which foreign AI operates within national borders,” rather than self-sufficiency or digital capabilities.[59]

In general, countries should adopt a language and framework of “advancing their digital capabilities” rather than “trying to achieve digital sovereignty.” The former would do far more to advance countries’ innovative and productive capabilities by taking maximal advantage of the capabilities of modern digital technologies.

Expand the Tariff Escalation to USMCA Products

So far, USMCA-qualifying goods have remained mostly out of the current administration’s trade war. Most products that qualify under USMCA rules of origin (ROOs) remain at 0 percent tariffs announced during the second Trump administration. This exempts over 90 percent of imports from Canada and 84 percent of imports from Mexico from the U.S. government’s tariffs.[60] The remaining goods from Canada are taxed at 35 percent, and those entering from Mexico are taxed at 25 percent (10 percent for potash).[61] However, the United States is imposing tariffs on Canadian and Mexican products that contain specific components, such as steel and aluminum.

The Trump administration should not impose sectoral tariffs on Canadian and Mexican imports, especially for inputs and intermediate goods critical to the American manufacturing industry. While the administration could use executive carve-outs or other temporary measures to exempt USMCA-qualifying goods from new tariffs, such alternatives would be inherently unstable and inefficient. Executive actions can replicate certain tariff benefits without reopening the agreement, but they fail to provide the predictability firms require for long-term investment and supply-chain planning. Moreover, the value of USMCA extends well beyond tariff elimination. The agreement embeds stronger disciplines on intellectual property, digital trade, regulatory transparency, and trade-remedy procedures that collectively underpin America’s competitiveness. Unilateral executive measures cannot substitute for these integrated, legally binding commitments. Moreover, as noted, the Trump administration should make the USMCA a wholly tariff-free trade zone.

Instead of raising tariffs on goods originating from the USMCA, the United States should prioritize encouraging Canada and Mexico to reverse policies that harm American technology companies. ITIF’s aforementioned Big Tech Policy Tracker—which catalogs more than 90 measures that disadvantage U.S. technology firms overseas—identifies several Canadian and Mexican policies that contradict these principles.[62] For instance, Canada’s Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) imposes strict conditions on cross-border data transfers, compelling U.S. companies to adopt costly, redundant local data systems instead of efficient, integrated networks.[63] Similarly, Mexico’s Cloud Service Restrictions introduce prescriptive data-management requirements for financial technology providers, constraining competition and limiting market access for U.S. cloud service firms.[64] Policymakers and trade negotiators should resolve these irritants through dialogue and digital trade cooperation first—rather than resorting to tariff escalation as a primary option.

Conclusions

Renewing the USMCA should remain a top priority for the Trump administration. The USMCA strengthens U.S. techno-economic power twofold: by expanding American supply chain networks by leveraging Canada’s and Mexico’s comparative advantages, and by weakening China’s manufacturing capacity by enabling reshoring investments and shifting imports from China to USMCA partners. The renewal of USMCA should be subject to Canada and Mexico fulfilling their previous commitments—particularly Mexico on intellectual property issues—and should include modernized provisions to shield the North American economy from Chinese mercantilism, as well as include updates to digital trade and IPR-related provisions.

Appendices

Proliferation of Digital Trade Agreements After USMCA Entered Force

Since the USMCA came into effect, new digital trade agreements and related initiatives have emerged, offering lessons and references for the USMCA review. Notable here are USMCA negotiations concluded before the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic crisis spurred a push, particularly among developing economies, to boost their digital economies, as digitalization among firms in those countries increased.[65] It raised awareness among policymakers about the need for digital trade rules—notably, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) urged the proliferation of digital trade agreements as a response to the crisis a few months after COVID-19 was declared a global pandemic.[66]

In this context, since 2020, there has been a notable expansion of digital trade agreements, digital economy agreements, and e-commerce or digital trade chapters within free trade agreements. Below is a description of the most relevant advances in digital trade agreements, by their relevance to U.S. policymaking:

▪ The World Trade Organization (WTO) Joint Statement Initiative on E-commerce (JSI). The WTO’s JSI concluded five years of negotiations in July 2024—notably with the United States pulling out from this deal.[67] The agreement sets common rules and provisions to enable cross-border e-commerce. JSI participants are committed to proceeding with the domestic legal process, as with any trade agreement, with the expectation of integrating the outcome of negotiations into the WTO legal framework.[68]

▪ General Review of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). The CPTPP chapter on e-commerce has served as a template for digitally related provisions in trade agreements since its inception in 2018.[69] In November 2023, CPTPP members agreed to conduct a general review of the agreement to assess its operation and identify provisions to update. Many CPTPP members have established an open consultation for this. The general review is expected to be concluded by the end of 2025, with the next steps outlined.[70]

The Pacific Economic Cooperation Council (PECC) released its recommendations in June 2025 for reforming the CPTPP’s e-commerce chapter.[71] PECC urges the CPTPP to adopt JSI as a baseline to formalize the CPTPP’s e-commerce chapter as the global template for digital trade rules. It also recommends turning this section into a “digital economy” chapter, administered by a secretariat to facilitate its operation and industry engagement, covering standards on cloud services, AI governance, cross-border data sharing, and digital trade infrastructure.

▪ Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). This “mega regional” trade agreement among the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) member states and Australia, China, Japan, New Zealand, and South Korea entered into force in 2022. China played a central role in the negotiations.[72]

But RCEP has weak enforcement mechanisms, and all provisions can be carved out on grounds of “national interest.” In fact, China, despite being a promoter of this agreement, does not meet the e-commerce provisions in several key areas. For instance, China falls short when it comes to implementing an electronic transaction law aligned with the principles of the UN Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) Model Law, adopting a non-discrimination approach to protect users from violations of personal information protection, ensuring free cross-border data flows, and refraining from implementing data localization requirements.[73]

▪ The European Union’s (EU) push for digital trade agreements. Europe has become a relevant actor in global digital rulemaking. The EU has traditionally encouraged its trade partners—especially those with weaker negotiation powers—to adopt the EU’s digital policies, which are characterized by the precautionary principle approach. This framework favors ex-ante regulation, preventing the adoption of digital technologies until it is certain that any potential negative externality is addressed. The expansion of this framework into other jurisdictions is known as the “Brussels effect.”[74]

The EU is now extending the “Brussels effect” to digital trade rules. The EU-Singapore Digital Trade Agreement (DTA) took effect in May 2025, while negotiations for the EU-South Korea DTA have concluded, and early discussions are underway for a possible DTA with Canada.[75] The “Brussels effect” is reflected in these agreements through the dominance of the precautionary principle, the emphasis on consumer protection over technology adoption, and carve-outs for cross-border data flows that enable EU officials to maintain strong privacy protections.[76]

▪ Digital Economy Partnership Agreement (DEPA). Signed by Chile, New Zealand, and Singapore, with South Korea’s accession in May 2024, this is a one-of-a-kind agreement that covers all aspects of the digital economy and e-commerce.[77] The DEPA sets clear, interoperable standards and best practices to ensure legal certainty in digital trade issues. Simultaneously, it supports an open and non-discriminatory global Internet as a foundation for emerging digital sectors like AI and creative industries.[78]

▪ ASEAN Digital Economy Framework Agreement (DEFA). Serving as a continuation of the ASEAN Agreement on E-Commerce signed in 2019, the DEFA will be the most significant South-South digital trade agreement globally.[79] The negotiations began in late 2023, concluded in October 2025, and the agreement is expected to be signed in 2026.[80] The DEFA negotiations have been using the CPTPP and DEPA as templates, and it is expected to incorporate language addressing Southeast Asia’s specific challenges, such as labor mobility and digital inclusion.[81]

Table 1 summarizes the main countries in the global network of digital trade agreements. Among USMCA partners, the United States is the only country not involved in these agreements. Canada is a CPTPP member and endorsed the JSI and, in August 2022, began discussions to initiate DEPA accession; as previously mentioned, it is also exploring a DTA with the EU.[82] Mexico, while less active than Canada, is a CPTPP member and endorsed JSI.

Table 1: Main e-commerce, digital trade, or digital economy agreements

|

Country |

CPTPP |

DEPA |

DEFA |

JSI |

RCEP |

Actively Negotiating Other DTAs |

|

Australia |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|||

|

Canada |

✓ |

▧ |

✓ |

▧ |

||

|

Chile |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|||

|

China |

▧ |

✓ |

✓ |

|||

|

European Union |

✓* |

▧ |

||||

|

Indonesia |

▧ |

✓ |

||||

|

Japan |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|||

|

Malaysia |

✓ |

▧ |

✓ |

✓ |

||

|

Mexico |

✓ |

✓ |

||||

|

New Zealand |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

||

|

Peru |

✓ |

▧ |

✓ |

|||

|

Singapore |

✓ |

✓ |

▧ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

South Korea |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

▧ |

||

|

Thailand |

▧ |

✓ |

✓ |

|||

|

The Philippines |

▧ |

✓ |

✓ |

|||

|

United Kingdom |

✓ |

✓ |

▧ |

|||

|

Vietnam |

✓ |

▧ |

✓ |

✓*: All 27 EU member states adhere separately as a country.

▧: Ongoing negotiations.

USMCA Digital Trade Rules Compared to Other Digital Trade Agreements

While the USMCA’s digital trade provisions cover, at their core, topics similar to those of the CPTPP and DEPA, the latter two agreements include more non-binding provisions on emerging issues—particularly DEPA. Table 2 summarizes which provisions are covered in the CPTPP’s e-commerce chapter, USMCA digital trade chapter, DEPA, RCEP’s e-commerce chapter, and the WTO’s JSI. DEPA, in particular, innovates by incorporating non-binding provisions on topics outside the USMCA scope, such as e-invoicing, e-payment, digital ID interoperability, AI principles, and data innovation for public services.

Table 2: Digital trade provisions in key agreements[83]

|

Provisions |

CPTPP |

USMCA |

DEPA |

RCEP |

WTO JSI |

|

Moratorium on customs duties on electronic transmissions and digital products |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

|

Non-discriminatory treatment for digital products |

● |

● |

● |

||

|

Ban on data localization |

● |

● |

● |

● |

|

|

Free cross-border transfer of personal information |

● |

● |

● |

● |

|

|

Protect consumers’ personal information |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

|

Consumer protection laws that define and prevent fraudulent and deceptive commercial activities |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

|

Measures against spam or unsolicited messages |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

|

Prohibit parties from forcing the transfer of source code as a condition for market access |

● |

● |

|||

|

Collaboration on cybersecurity management |

○ |

○ |

○ |

○ |

○ |

|

Safe harbour for Internet intermediaries |

● |

||||

|

Open government data |

○ |

○ |

○ |

● |

|

|

Interoperable electronic invoicing |

● |

● |

|||

|

Interoperable electronic payment system |

○ |

● |

|||

|

Interoperable digital identities |

○ |

○ |

|||

|

Cooperation in the fintech sector |

○ |

○ |

|||

|

Ethical governance of AI |

○ |

||||

|

Data innovation |

○ |

||||

|

Digital innovation and emerging technologies |

○ |

||||

|

Logistics best practices |

○ |

● |

|||

|

Standards and technical regulations |

○ |

||||

|

Open Internet access to consumers |

○ |

○ |

○ |

● |

|

|

Cooperation on digital inclusion |

○ |

● |

●: Binding provision.

○: Non-binding provision

Endnotes

[1] Christopher E. Wilson, “Working Together: Economic Ties Between the United States and Mexico” (Mexico Institute, Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, November 2011), https://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/working-together-economic-ties-between-the-united-states-and-mexico.

[2] M. Angeles Villarreal, Liana Wong, and Alice B. Grossman, “USMCA: Motor Vehicle Provisions and Issues” (Congressional Research Service, updated October 14, 2021), https://www.congress.gov/crs_external_products/IF/PDF/IF11387/IF11387.8.pdf; David A. Gantz, “The United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement: Tariffs, Customs, and Rules of Origin” (Houston, Texas: Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy, February 21, 2019), https://www.bakerinstitute.org/research/united-states-mexico-canada-agreement-tariffs-customs-and-rules-origin.

[3] Nikia Clarke, “A Note from Nikia: WTCSD on Trade,” San Diego Regional Economic Development Corporation, February 12, 2025, https://www.sandiegobusiness.org/blog/a-note-from-nikia-wtcsd-on-trade/.

[4] Stephen J. Ezell and Caleb Foote, “Global Trade Interdependence: U.S. Trade Linkages With Korea, Mexico, and Taiwan” (Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF), June 2019), https://www2.itif.org/2019-global-trade-interdependence.pdf.

[5] Robert D. Atkinson, “We Are in an Industrial War. China Is Starting to Win,” New York Times, January 9, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/01/09/opinion/china-industrial-war-power-trader.html.

[6] International Monetary Fund (IMF), “World Economic Outlook, October 2025” (IMF, 2025).

[7] Robert D. Atkinson and Ian Tufts, “The Hamilton Index, 2023: China Is Running Away With Strategic Industries” (ITIF, December 13, 2023), https://itif.org/publications/2023/12/13/2023-hamilton-index/.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid; Data updated as of October 31, 2025.

[10] Ibid; Data updated as of October 31, 2025.

[11] Shefali Kapadia, “To move or not to move? Manufacturers hesitant to nearshore before USMCA review,” Manufacturing Dive, October 14, 2025, https://www.manufacturingdive.com/news/usmca-us-mexico-canada-tariff-trade-manufacturing/802550/.

[12] MND Staff, “Semiconductor manufacturer Micron Technology coming to Guadalajara,” Mexico News Daily, May 10, 2024, https://mexiconewsdaily.com/nearshoring-in-mexico/micron-technology-micro-chip-factory-mexico/.

[13] Hyunjoo Jin and Brenda Goh, “Exclusive: Micron to exit server chips business in China after ban, sources say,” Reuters, October 17, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/business/autos-transportation/micron-exit-server-chips-business-china-after-ban-sources-say-2025-10-17/.

[14] Henry Cesari, “Ford stockpiling Canadian-built V8s ahead of tariffs,” MotorBiscuit, March 21, 2025, https://www.motorbiscuit.com/ford-stockpiling-canada-v8s-tariffs/.

[15] Chris Isidore, “Trump says he’ll protect US-made cars through steep tariffs, but there is no such thing as an all-American car,” CNN, December 2, 2024, https://www.cnn.com/2024/11/27/business/car-prices-tariffs.

[16] Stephen Ezell, “Don’t Let Chinese EV Makers Manufacture in the United States” (ITIF, September 17, 2025), https://itif.org/publications/2025/09/17/dont-let-chinese-ev-makers-manufacture-in-the-united-states/.

[17] U.S. Customs and Border Protection and Department of the Treasury, “Non-Preferential Origin Determinations for Merchandise Imported From Canada or Mexico for Implementation of the Agreement Between the United States of America, the United Mexican States, and Canada (USMCA),” Federal Register 86, No. 126 (July 6, 2021): 35422–29, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2021/07/06/2021-14265/non-preferential-origin-determinations-for-merchandise-imported-from-canada-or-mexico-for.

[18] Duncan Wood, “6 Top Issues To Review in U.S.-Mexico-Canada Trade,” The Hill, June 21, 2025 https://thehill.com/opinion/international/5357376-usmca-review-north-america/.

[19] Eliot Chen, “Canada Set to Side With China on EVs,” The Wire China, October 26, 2025, https://www.thewirechina.com/2025/10/26/canada-set-to-side-with-china-on-evs/.

[20] Robert D. Atkinson, “How to Mitigate the Damage From China’s Unfair Trade Practices by Giving USITC Power to Make Them Less Profitable” (ITIF, November 2022), https://itif.org/publications/2022/11/21/how-to-mitigate-the-damage-from-chinas-unfair-trade-practices/.

[21] Nigel Cory, “Comments to the USTR Regarding the Work of the North American Competitiveness Committee” (ITIF, July 18, 2023), https://itif.org/publications/2023/07/18/comments-to-the-ustr-regarding-work-of-north-american-competitiveness-committee/.

[22] United State’s Trade Representative’s Office, “USMCA Agreement: Article 26.1: North American Competitiveness Committee,” https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/files/agreements/FTA/USMCA/Text/26_Competitiveness.pdf.

[23] Luke Dascoli and Stephen Ezell, “The North American Subnational Innovation Competitiveness Index” (ITIF, June 2022), https://www2.itif.org/2022-north-american-index.pdf.

[24] Agreements related to the digital economy refers to digital trade or e-commerce chapters of free trade agreements, digital trade agreements, or digital economy agreements.

[25] Nigel Cory and Luke Dascoli, “How Barriers to Cross-Border Data Flows Are Spreading Globally, What They Cost, and How to Address Them” (ITIF, July 2021), https://itif.org/publications/2021/07/19/how-barriers-cross-border-data-flows-are-spreading-globally-what-they-cost/.

[26] Lilla Nóra Kiss, “Does the DMA Intentionally Target US Companies?” (ITIF, March 21, 2025, https://itif.org/publications/2025/03/21/does-the-dma-intentionally-target-us-companies/.

[27] Lilla Nóra Kiss, “Six Ways the DMA Is Backfiring on Europe by Harming Users, Innovation, and Allies” (ITIF, June 30, 2025), https://itif.org/publications/2025/06/30/six-ways-the-dma-is-backfiring-on-europe/.

[28] Hilal Aka, “Tip of the Iceberg: Understanding the Full Depth of Big Tech’s Contribution to US Innovation and Competitiveness” (ITIF, October 6, 2025), https://itif.org/publications/2025/10/06/tip-of-the-iceberg-understanding-big-techs-contribution-us-innovation-competitiveness/.

[29] Nigel Cory and Samm Sacks, “China Gains as U.S. Abandons Digital Policy Negotiations,” Lawfare, November 15, 2023, https://www.lawfaremedia.org/article/china-gains-as-u.s.-abandons-digital-policy-negotiations.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement, “Chapter 12: Electronic Commerce” (November 15, 2020), https://fta.mofcom.gov.cn/rcep/rceppdf/d12z_en.pdf.

[32] The White House, “Promoting the Export of the American AI Technology Stack,” Executive Order 14320, July 23, 2025, www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/07/promoting-the-export-of-the-american-ai-technology-stack/.

[33] Rodrigo Balbontin, “Backfire: Export Controls Helped Huawei and Hurt U.S. Firms” (ITIF, October 27, 2025), https://itif.org/publications/2025/10/27/backfire-export-controls-helped-huawei-and-hurt-us-firms/.

[34] The Asia Foundation, “Digital Trade Agreements in Asia and the Pacific” (The Asia Foundation, March 2024), https://asiafoundation.org/publication/digital-trade-agreements-in-asia-and-the-pacific/.

[35] Government of Chile; Government of New Zealand; and Government of Singapore, “Digital Economy Partnership Agreement (DEPA): Signing Text, June 11, 2020 (GMT)” https://www.subrei.gob.cl/docs/default-source/default-document-library/depa-signing-text-11-june-2020-gmt.pdf?sfvrsn=43d86653_2.

[36] ITIF, “Big Tech Policy Tracker,” https://itif.org/publications/knowledge-bases/big-tech/.

[37] Joe Kennedy, “Digital Services Taxes: A Bad Idea Whose Time Should Never Come” (ITIF, May 13, 2019), https://itif.org/publications/2019/05/13/digital-services-taxes-bad-idea-whose-time-should-never-come/.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Ashley Johnson and Daniel Castro, “Overview of Section 230: What It Is, Why It Was Created, and What It Has Achieved” (ITIF, February 22, 2021), https://itif.org/publications/2021/02/22/overview-section-230-what-it-why-it-was-created-and-what-it-has-achieved/.

[40] Daniel Castro, “Analysis of Weakening or Repealing Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act,” in Crossroads of Innovation and Liability: Brazil and the U.S.’s Digital Regulation Strategies, ed. Bruna Santos (Wilson Center Brazil Institute, April 2024), https://itif.org/publications/2024/04/08/analysis-of-weakening-or-repealing-section-230-of-the-communications-decency-act/.

[41] Office of the United States Trade Representative, “United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement Fact Sheet: Intellectual Property,” https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/files/Press/fs/USMCA/USMCA_IP.pdf/

[42] Office of the United States Trade Representative, “USTR Releases 2025 Special 301 Report on Intellectual Property Protection and Enforcement,” press release, April 29, 2025, https://ustr.gov/about/policy-offices/press-office/press-releases/2025/april/ustr-releases-2025-special-301-report-intellectual-property-protection-and-enforcement.

[43] Ibid.

[44] U.S. Chamber of Commerce, Global Innovation Policy Center (GIPC), “International IP Index: 2025 Thirteenth Edition” (CIPC, April 15, 2025), https://www.uschamber.com/assets/documents/GIPC_IPIndex2025_Combined_final.pdf/

[45] FisherBroyles, “Mexican President Sends a Proposed IP Reform to the Senate, Including Sweeping Changes and Innovations,” September 17, 2025, https://fisherbroyles.com/news/mexican-president-sends-a-proposed-ip-reform-to-the-senate-including-sweeping-changes-and-innovations/.

[46] Rodrigo Balbontin, “Blocking Access to Foreign Pirate Sites: A Long-Overdue Task for Congress” (ITIF, June 9, 2025), https://itif.org/publications/2025/06/09/blocking-access-to-foreign-pirate-sites-a-long-overdue-task-for-congress/.

[47] Ibid.

[48] Office of the United States Trade Representative, “Protocol of Amendment to the Agreement Between the United States of America, the United Mexican States, and Canada,” December 10, 2019, https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/files/agreements/FTA/USMCA/Protocol-of-Amendments-to-the-United-States-Mexico-Canada-Agreement.pdf.

[49] Big Molecule Watch (Goodwin Procter LLP), “10-Year Data Exclusivity for Biologics Removed from Final USMCA Agreement,” December 13, 2019, https://www.bigmoleculewatch.com/2019/12/13/10-year-data-exclusivity-for-biologics-removed-from-final-usmca-agreement/.

[50] Stephen Ezell, “Ensuring the Trans-Pacific Partnership Becomes a Gold-Standard Trade Agreement” (ITIF, August 2012), 8, http://www.itif.org/publications/ensuring-trans-pacific-partnership-becomes-gold-standard-trade-agreement.

[51] Wyss Institute, “Human Biology: An Exploration of Organs-on-Chips,” https://wyss.harvard.edu/event/human-biology-an-exploration-of-organs-on-chips/.

[52] GIPC, “International IP Index: 2025 Thirteenth Edition.”

[53] Alex Riehl, “Carney says new Major Projects Office will help build a ‘Canadian sovereign cloud’,” BetaKit, September 11, 2025, https://betakit.com/carney-says-new-major-projects-office-will-help-build-a-canadian-sovereign-cloud/.

[54] Ibid.

[55] Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, “Canadian Sovereign AI Compute Strategy,” https://ised-isde.canada.ca/site/ised/en/canadian-sovereign-ai-compute-strategy.

[56] Alejandro González, “Sheinbaum: soberanía digital para erradicar dependencia tecnológica,” DPL News, September 23, 2025, https://dplnews.com/sheinbaum-soberania-digital-erradicar-dependencia-tecnologica/.

[57] Ibid.

[58] The White House, “Remarks by Director Kratsios at the APEC Digital and AI Ministerial Meeting,” August 5, 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/articles/2025/08/remarks-by-director-kratsios-at-the-apec-digital-and-ai-ministerial-meeting/.

[59] Hodan Omaar, “AI Sovereignty Makes Everyone Weaker—America Can Lead Differently,” (ITIF, September 4, 2025), https://itif.org/publications/2025/09/04/ai-sovereignty-makes-everyone-weaker-the-us-can-lead-differently/.

[60] Rob Gillies, “Crucial exemption allows majority of Canadian and Mexican goods to be shipped to US without tariffs,” AP News, August 5, 2025, https://apnews.com/article/trump-tariffs-canada-mexico-exemption-969a4cfb03638ce9d6c0ffad2b98b4b1.

[61] Global Business Alliance, “GBA Tariff Tracker,” updated October 28, 2025, https://globalbusiness.org/gba-tariff-tracker/.

[62] ITIF, “Big Tech Policy Tracker.”

[63] ITIF, “Canada’s Cross-Border Data Transfer Regulation,” (knowledge base), last updated August 26, 2025, https://itif.org/publications/2025/06/09/canada-cross-border-data-transfer-regulation/.

[64] ITIF, “Mexico’s Cloud Service Restrictions,” (knowledge base), last updated August 26, 2025, https://itif.org/publications/2025/05/25/mexico-cloud-service-restrictions/.

[65] Edgar Avalos, Xavier Cirera, Marcio Cruz, Leonardo Iacovone, Denis Medvedev, Gaurav Nayyar, and Santiago Reyes Ortega, “Firms’ Digitalization during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Tale of Two Stories,” Policy Research Working Paper 10284 (World Bank, January 2023), https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/entities/publication/6f12961f-0cb8-4998-ab8c-32f4613ffef1.

[66] Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Leveraging Digital Trade to Fight the Consequences of COVID-19 (July 7, 2020), https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/leveraging-digital-trade-to-fight-the-consequences-of-covid-19_f712f404-en/full-report.html#section-d1e1156.

[67] World Trade Organization, “Joint Statement Initiative on E-commerce,” https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/ecom_e/joint_statement_e.htm.

[68] Ibid.

[69] The Asia Foundation, Digital Trade Agreements in Asia and the Pacific.

[70] Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Terms of Reference for Conducting the General Review of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) endorsed at CPTPP Ministerial meeting on 15 November 2023 PST (November 15, 2023), https://www.dfat.gov.au/trade/agreements/in-force/cptpp/terms-reference-conducting-general-review-comprehensive-and-progressive-agreement-trans-pacific-partnership-cptpp-endorsed-cptpp-ministerial-meeting-15-november-2023-pst.

[71] Pacific Economic Cooperation Council (PECC), Report of the Track 1.5 Process to Review and Update the CPTPP Chapter 14 on Electronic Commerce (PECC, June 25, 2025), https://funpacifico.cl/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/PECC-Report-CPTPP-E-Commerce-Track-1.5-25062025.pdf.

[72] Cathleen D. Cimino-Isaacs, Ben Dolven, and Michael D. Sutherland, Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), CRS In Focus IF11891 (Congressional Research Service, October 17, 2022), https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/IF11891.

[73] The Asia Foundation, Digital Trade Agreements in Asia and the Pacific.

[74] Kiss, The Brussels Effect: How the EU’s Digital Markets Act Projects European Influence.

[75] European Commission, “EU and Singapore Sign Landmark Digital Trade Agreement” (Press release, May 6, 2025), https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_25_1152; European Commission, Directorate-General for Trade, “EU-South Korea agreements: Documents,” https://policy.trade.ec.europa.eu/eu-trade-relationships-country-and-region/countries-and-regions/south-korea/eu-south-korea-agreements/documents_en; Global Affairs Canada, “Consulting Canadians on a Possible Canada–European Union Digital Trade Agreement,” June 23, 2025, https://international.canada.ca/en/global-affairs/consultations/trade/2025-06-23-digital-trade.

[76] Ludovica Favarotto, “Data, Deals, and Partnership: The European Union’s Rise as a Digital Trade Leader” (ISPI, April 15, 2025), https://www.ispionline.it/en/publication/data-deals-and-partnership-the-european-unions-rise-as-a-digital-trade-leader-205847.

[77] Subsecretaría de Relaciones Económicas Internacionales (SUBREI), “DEPA – Digital Economy Partnership Agreement,” https://www.subrei.gob.cl/en/landings/depa.

[78] Ibid.

[79] Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), “Digital Economy Framework Agreement (DEFA): ASEAN to Leap Forward Its Digital Economy and Unlock US$2 Trillion by 2030,” August 19, 2023, https://asean.org/asean-defa-study-projects-digital-economy-leap-to-us2tn-by-2030/.

[80] ASEAN Economic Community Council, “Statement on the Substantial Conclusion of the ASEAN DEFA Negotiations,” October 24, 2025, PDF, https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/ADOPTED-AECC-Statement-on-Substantial-Conclusion-of-DEFA-Negotiations-24Oct2025.docx.pdf.

[81] Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), Digital Economy Framework Agreement (DEFA): ASEAN to Leap Forward Its Digital Economy and Unlock US$2 Trillion by 2030.

[82] Ministry of Trade and Industry (Singapore), “Digital Economy Partnership Agreement (DEPA),” https://www.mti.gov.sg/Trade/Digital-Economy-Agreements/The-Digital-Economy-Partnership-Agreement.

[83] The Asia Foundation, Digital Trade Agreements in Asia and the Pacific; and World Trade Organization, Joint Statement Initiative on Electronic Commerce.