Comments to USTR for Its Section 301 Investigation of China’s Implementation of Commitments Under the Phase One Agreement

Contents

Overview: China Is Not a Reliable Partner and It Does Not Intend to Change Its Nonmarket Approach 3

China’s State-Led Economic Model Stands at Odds With Market Economy Principles 3

China’s Development Playbook Is at Odds With What It Committed to Under the Phase One Agreement 5

How the PRC Uses Non-Market Policies to Gain an Advantage in Strategic Sectors 6

China Supports Its EV Producers to Underprice Competitors in Global Markets 6

China Is Supporting the Overproduction of Polysilicon to Secure Global Dominance. 7

China Helped Huawei to Subsist Despite U.S. Sanctions 7

China Confers an Unfair Advantage to Its E-commerce Platforms 7

China Failed to Meet Its Commitments Under the Phase One Agreement 8

China Failed to Meet Its Purchasing Commitments 8

China Continues to Infringe Upon American Intellectual Property 9

China Deploys Economic Espionage Campaigns Against the United States 10

China Facilitates the Flow of Counterfeits Into the United States 10

China Continues to Force Technology Transfer on Foreign Investors 11

Introduction and Summary

The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) is pleased to submit the following comments for consideration by the Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR) for the Request for Comments on the Section 301 Investigation of China’s Implementation of Commitments under the Phase One Agreement. ITIF is an independent, nonprofit, nonpartisan research and educational institute focusing on the intersection of technological innovation and public policy.

China has failed to meet its commitments under the U.S.-China Phase One Agreement (POA).[1] This agreement sought to address long-standing U.S. concerns about China’s predatory practices by pairing existing tariffs with commitments from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) on intellectual property (IP) and technology transfer, foreign investment, and currency practices. It also included a two-year, $200 billion purchase pledge.[2] This filing shows that China failed to meet its commitments across all of these aspects.

China is not a reliable trade partner, as potential commitments to reverse its predatory practices are antithetical to its long-term techno-economic project. This filing first provides evidence of ITIF’s work on Chinese non-market practices by detailing a 2021 ITIF report on China’s failure to meet its commitments under its World Trade Organization (WTO) accession. Then, it succinctly shows ITIF’s work assessing China’s global power project and its playbook of predatory, non-market practices to achieve it. This section concludes with examples of how this project gets translated into building critical sectors and boosting Chinese companies and industries.

The following section details how China failed to meet its purchasing commitments and summarizes ITIF’s recent work on China’s economic espionage and its role in facilitating the entry of counterfeits into the U.S. market.

Finally, the document concludes with recommendations to USTR. First, the current Section 301 investigation will allow the U.S. government to impose tariffs on Chinese manufacturers that continue to benefit from innovation mercantilist practices. Second, ITIF proposes using Section 301 authorities to impose import controls on goods from Entity List companies, exclude IP-infringing companies from the U.S. market, and impose “immediate reciprocity” in sectors where mercantilist practices forcefully limit the U.S. presence in the Chinese market.

Table 1: POA commitments that China has failed to fully meet

|

Issue |

Commitment |

Has China Lived Up to the POA? |

|

Trade imbalance |

China pledged to buy $200 billion more U.S. goods and services than in 2017 over the 2020–2021 period, including extra purchases in agriculture, energy, manufacturing, and services. |

No |

|

Intellectual property |

China agreed to stronger protections for trade secrets, easier proof of misappropriation, and patent-term extensions for delayed drug patents. |

No |

|

Technology transfer |

China committed not to force or pressure foreign firms to transfer technology and to keep any tech deals voluntary and market-based. |

No |

|

Foreign investment and acquisitions |

China agreed not to subsidize outbound investments that target foreign technologies highlighted in its industrial plans. |

No |

|

Currency |

China committed to more market-based exchange rates and greater transparency on its currency practices. |

No |

Overview: China Is Not a Reliable Partner and It Does Not Intend to Change Its Nonmarket Approach

The Chinese government has a long record of broken promises, promoting nominally fair policies while aggressively imposing nonmarket interventions to support its local industries. The list of deceptive promises and statements is long. For example, in September 2015, in Seattle, Washington, Xi Jinping stated that “the Chinese government will not, in whatever form, engage in commercial theft or encourage or support such attempts by anyone.”[3] In July 2018, the PRC’s State Council released a statement indicating that “China has never had a policy of forcing technology transfers from foreign companies.”[4] Most recently, in April 2025, the Ministry of Commerce stated that China would protect the “legitimate rights and interests of foreign-funded enterprises in accordance with the law, and actively promote the resolution of foreign-funded enterprises.”[5] These promises are misleading because they commit to doing things (i.e., implementing market-based policies) that are antithetical to the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) project. Indeed, China has clearly failed to fulfill the commitments it made to peer nations as a condition for joining the WTO, especially the promise to manage its trade and economic activities in line with the core WTO principles of national treatment, non-discrimination, and reciprocity.

China’s State-Led Economic Model Stands at Odds With Market Economy Principles

China’s economic success represents a tale of mercantilism and state-driven non-market interventions (including subsidizing overproduction, stealing IP, and forcing technology transfer or foreign direct investment from companies) on the one hand, and complacency and naivety from Western policymakers on the other hand. ITIF’s 2021 report “False Promises II: The Continuing Gap Between China’s WTO Commitments and Its Practices” enumerated 12 high-level examples of how China has systematically and consistently failed to meet its WTO commitments:[6]

▪ Rejecting the WTO’s market orientation. China has never truly embraced the WTO’s core premise of open, market-oriented policies guided by commercial, rather than political, considerations. Instead, Beijing operates a “China Inc.” system in which the party-state routinely intervenes to steer outcomes, undercutting the basic assumption that market forces drive competition.

▪ Defying WTO norms through state-led industrial planning. China’s industrial strategies—exemplified by “Made in China 2025” and a lattice of sectoral plans—explicitly seek absolute advantage in advanced industries by displacing foreign firms at home and expanding Chinese firms’ global market share abroad. These state-directed schemes violate the spirit of WTO rules, which presume that governments will not use industrial planning to rig competitive outcomes in favor of domestic champions.

▪ Continuing prevalence of and preferences for state-owned enterprises (SOEs). Contrary to its commitments, China has not reduced the role of state-owned enterprises or ensured that they operate on a purely commercial basis. SOEs continue to receive privileged financing, regulatory forbearance, and preferential access to public procurement and key inputs, distorting competition in both China’s domestic market and global markets.

▪ Massively subsidizing its industries, often leading to overcapacity. Beijing deploys extensive, often opaque subsidies—grants, tax breaks, cheap land, and below-market finance—to accelerate capacity growth in targeted sectors such as steel, aluminum, solar, shipbuilding, autos, semiconductors, and many other sectors. The result is chronic overcapacity that depresses global prices, displaces more efficient producers in market economies, and undermines the WTO’s goal of fair, rules-based competition.

▪ Failing to make timely and transparent notifications of subsidies. China has systematically failed to provide full, timely, and accurate notifications of its subsidy programs, despite clear obligations to do so under WTO rules. This lack of transparency makes it exceedingly difficult for other members to assess the scale and impact of China’s support measures or to challenge them effectively through WTO processes.

▪ Forcing technology transfer and joint venture requirements. Beijing continues to use a mix of formal and informal tools—joint-venture requirements, equity caps, licensing demands, administrative reviews, and regulatory approvals—to coerce foreign firms into transferring technology as the price of market access. These practices violate both the letter and spirit of China’s WTO commitments to refrain from conditioning investment or trade on technology transfer requirements.

▪ Failing to respect foreign IP rights. While China has improved its IP laws on paper, enforcement remains weak, selective, and often politicized, leaving foreign firms exposed to theft and misappropriation of trade secrets, patents, and copyrights. Persistent large-scale IP infringement and limited effective remedies demonstrate that China has not delivered on its obligation to provide robust, non-discriminatory protection for foreign IP.

▪ Abusing antitrust rules. Chinese competition authorities have frequently wielded antitrust law as an industrial-policy tool, targeting foreign firms for investigations, remedies, and fines that appear designed to force technology transfer, lower royalty rates, or advantage domestic rivals. Rather than applying competition rules on a neutral basis, China often uses them to pursue strategic industrial goals inconsistent with WTO expectations.

▪ Imposing discriminatory technology standards. China’s standards system remains heavily state-managed and is frequently used to advance domestic technologies and firms at the expense of foreign competitors. Standards are often developed in closed processes, embed design choices that favor Chinese products, and can be tied to mandatory certification schemes, contravening WTO principles of transparency, non-discrimination, and open participation.

▪ Closing its government procurement to foreign actors. Despite longstanding commitments, China has neither acceded to the WTO Government Procurement Agreement nor provided equivalent market access to foreign competitors. Chinese authorities continue to favor domestic firms—especially SOEs��in procurement decisions, using public purchasing as another lever to bolster national champions and restrict reciprocal opportunities for foreign companies.

▪ Continuing use of service-market access restrictions. China maintains extensive barriers to foreign participation in key service sectors—including finance, telecommunications, cloud computing, audiovisual services, and digital platforms—through equity caps, licensing hurdles, and other entry restrictions. These measures fall far short of the openness implied by China’s WTO commitments and deny foreign providers meaningful, non-discriminatory access.

▪ Using retaliatory trade remedies. Beijing has repeatedly used antidumping, countervailing duty, and other trade-remedy investigations in ways that appear retaliatory rather than grounded in objective economic analysis. Such actions are aimed at pressuring trading partners and deterring legitimate complaints about Chinese practices, further eroding confidence in the WTO’s rules-based system.

China’s Development Playbook Is at Odds With What It Committed to Under the Phase One Agreement

ITIF’s November 2025 report “Marshaling National Power Industries to Preserve America’s Strength and Thwart China’s Bid for Global Dominance,” among other topics, outlines China’s strategy for techno-economic dominance.[7] The PRC is executing a coordinated, state-directed campaign across “national power industries”—advanced, traded sectors that underpin military strength and geostrategic leverage—to attempt to attain hegemony over Western democracies. This scheme is inseparable from a durable, non-market playbook built around heavy subsidization and systematic distortion of competition. China follows a predictable strategy across industries: attract foreign investment, coerce tech transfer and steal foreign IP, provide massive subsidies, close domestic markets, and then capture global market share.[8]

The report succinctly outlines the Chinese Communist Party’s playbook:

The first step is to attract foreign investment. (...) China is still trying to do that today with emerging industries, seeking, for example, to attract global biopharmaceutical companies to build facilities in China. China’s second step is to attempt to learn from foreign companies, in part by having them train Chinese executives, scientists, and engineers, and also by forced technology transfer, including through joint ventures. (...) The third step is to support Chinese companies in their efforts to copy and incorporate foreign technology while building up domestic capabilities. (...) The fourth step is to enable Chinese firms to become independent innovators. (...) The Chinese market essentially becomes dominated by Chinese-owned firms. We have seen this an array of industries, including chemicals, telecom equipment, heavy construction equipment, high-speed rail, and renewable energy.[9]

In addition, the CCP integrates technological security into the PRC’s broader national security framework, blurring the line between economic and military statecraft. ITIF’s February 2025 report, “A Policymaker’s Guide to China’s Technology Security Strategy,” describes China’s three-tiered approach to achieve technology security.[10] First, China aims to preserve and fortify its existing competitive advantages, using industrial upgrading, its dense supply chains, and non-market interventions to lock-in global leadership in advanced manufacturing sectors such as electronics, solar, and electric vehicle (EV) batteries Secondly, the PRC is focused on rapidly closing critical technology gaps, especially in chokepoint inputs such as semiconductors, by pouring state resources into import substitution and self-reliance. Third, the Chinese government uses unrestricted access to large pools of data from its population to achieve dominance in emerging technologies, such as AI and other frontier technologies, to shape global standards and outpace competitors over the long term.[11]

How the PRC Uses Non-Market Policies to Gain an Advantage in Strategic Sectors

ITIF’s work since 2020, the year of the POA’s signing, has accumulated substantial evidence of China’s non-market approach to gain an advantage in strategic industries—at the detriment of U.S. and Western companies.

China Supports Its EV Producers to Underprice Competitors in Global Markets

ITIF’s September 2025 report, “Don’t Let Chinese EV Makers Manufacture in the United States,” shows China’s aggressive use of a range of mercantilist practices to advance in the EV market.[12] These non-market interventions include:

▪ Subsidies, totaling over $230 billion between 2009 and 2023, with an estimated $120 billion across 2021–2023 alone.

▪ Forced technology transfer and IP theft. For example, GM’s Volt model could qualify for subsidies only if the company was willing to “transfer the engineering secrets for one of the Volt’s three main technologies to a joint venture in China with a Chinese automaker.”[13] Other examples include forcing the hiring of Chinese engineers to establish a Ford research and development (R&D) facility in China, and Tesla suing a Chinese chip designer for infringing on its IP and stealing its trade secrets, both related to the integrated circuits it uses in its vehicles.[14]

▪ Favoring domestic companies. For example, Made in China 2025 included a local market share target for local producers, and most recently, local authorities have instructed Chinese automakers to avoid foreign semiconductors if at all possible.[15]

China Is Supporting the Overproduction of Polysilicon to Secure Global Dominance

ITIF’s September 2025 report, “China Plans to Dominate a Key Semiconductor Material,” describes the mechanisms by which the PRC’s government incentives, support, and massive overcapacity are flooding the global polysilicon market—a critical chipmaking material.[16] China’s interventions include financial subsidies and incentives, infrastructure and land support, and strategic national plans. China supports polysilicon overproduction and simultaneously helps producers offset the low prices it drives.[17]

The artificial decline in global prices created by the Chinese government’s intervention undermines the viability of U.S. polysilicon producers. While some estimates set the fair market price for polysilicon at $24/kg, Chinese firms are selling at approximately $5/kg, about $1 below their production cost.[18] This dumping cost Chinese producers $40 billion in 2024. This directly impacts U.S. producers. For example, Wolfspeed—a silicon carbide producer headquartered in North Carolina—closed two facilities in the United States in 2024 and postponed an expansion in Germany.

China Helped Huawei to Subsist Despite U.S. Sanctions

ITIF’s October 2025 report, “Backfire: Export Controls Helped Huawei and Hurt U.S. Firms,” describes how Huawei received support from the Chinese government to offset the export controls the United States imposed on the company since 2019.[19] Before these restrictions, Huawei had already received $75 billion in state support since its establishment. After the export controls, the Chinese government’s support for the company was manifested in three main ways:

▪ Favorable financial support to mitigate the effects of the export controls, such as the $15 billion acquisition of Honor, a budget-brand maker and former Huawei subsidiary, by a consortium of private and state-backed investors. This sale provided liquidity to Huawei and helped Honor avoid U.S. export controls.

▪ Direct procurement from state-owned Chinese companies, for example, the 2021 announcement that the Chinese state-owned China Mobile would acquire 60 percent of 5G network station contracts from Huawei.

▪ Continued preferential treatment as a “national champion” for strategic national initiatives, such as receiving an R&D tax incentive for semiconductors, which acts as a de facto subsidy by allowing a 220 percent deduction from the company’s taxable income. (Tax incentives are appropriate tools to facilitate semiconductor-industry competitiveness, but they should be made available equally to any foreign company competing in a country’s marketplace; yet, the subsidies extended to Huawei and other Chinese national champions were unique and exclusive.)

China Confers an Unfair Advantage to Its E-commerce Platforms

China has expanded globally through its international-facing e-commerce platforms, especially Temu, SHEIN, AliExpress, and TikTok Shop. As documented in ITIF’s April 2025 report “How China’s State-Backed E-Commerce Platforms Threaten American Consumers and U.S. Technology Leadership,” China’s government uses a coordinated industrial policy architecture to benefit these platforms through subsidized logistics, tax exemptions, talent recruitment programs, and state-directed financing through cross-border e-commerce pilot zones.[20] These industrial policies are not widely available to foreign competitors and sharply reduce Chinese platforms’ marginal costs of shipping, warehousing, marketing, and customer acquisition. China also deploys regulatory shields that suppress compliance obligations at home, enabling its national champions to achieve lower operating costs than any U.S. or allied-market platform could legally achieve.

These state-backed cost advantages translate into aggressive, predatory penetration of the U.S. market at prices that no market-based firm can realistically match. China’s industrial policy, which aims (as in many other industries) to gain global market share in e-commerce, also pushes its platforms to exploit gaps in U.S. regulations to reduce costs relative to domestic competitors. This raises consumer protection concerns by externalizing product-safety, data-security, and compliance risks onto American consumers, as seen with Temu’s September 2025 penalty for violating the INFORM Consumers Act.[21]

China Failed to Meet Its Commitments Under the Phase One Agreement

The POA included essential commitments by the PRC, as well as provisions related to IP, technology transfer, foreign investment and acquisitions, and currency.[22] The Chinese government has failed to fulfill any of these commitments. This section will outline how China failed to meet its purchasing commitments to reduce the trade imbalance with the United States and present further evidence of the PRC’s tolerance for IP infringement. While the previous section explained how the PRC permits technology transfer and manipulates foreign investments to benefit its EV companies, this section will provide further examples of forced technology transfer. Finally, regarding China’s currency commitments, the U.S. Department of the Treasury has consistently reported that “China provides very limited transparency regarding key features of its exchange rate mechanism, including the policy objectives of its exchange rate management regime and its activities in the offshore RMB market.”[23]

China Failed to Meet Its Purchasing Commitments

China agreed to purchase at least $200 billion worth of goods above a 2017 sectoral baseline across 2020 and 2021, but it only procured a fraction of that amount.[24] The purchasing commitments implied that China should have purchased $32 billion more in agricultural products, $52.4 billion in energy, $77.7 billion in manufactured goods, and $37.9 billion more in services.[25] However, China failed to meet its own purchasing commitments. By 2020, it had already fallen short of this commitment by 40 percent, and by 2021, it had met only 58 percent of the overall target.[26]

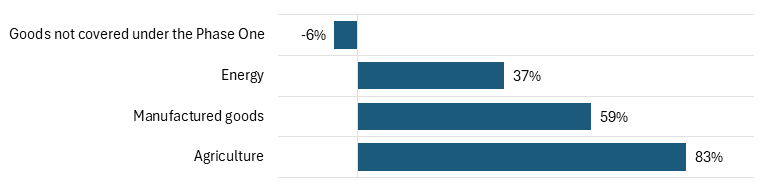

Figure 1 shows U.S. exports to China based on the POA purchasing commitments by sector. China focused on expanding its purchases of U.S. agricultural goods, but reached only 83 percent of the agreed amount. Additionally, U.S. exports to China declined by 6 percent during 2020–2021 for goods not covered under the POA.

Figure 1: U.S. exports to China across 2020 and 2021 as a share of China’s purchase commitments under the Phase One Agreement.[27]

China Continues to Infringe Upon American Intellectual Property

The PRC’s commitments regarding improving IP protection mechanisms include reforming internal mechanisms to address the U.S. government’s concerns regarding trade secrets, pharmaceutical-related IP, geographical indications, trademarks, and enforcement against pirated and counterfeit goods.[28] However, the PRC’s attempts to steal U.S. technologies persist unabated. In addition to the cases of IP infringement in EV markets described in the previous section, USTR has consistently reported China’s lack of IP enforcement, including Chinese companies and markets in the Notorious Markets List report, classifying China as part of the Priority Watch List in its 2025 Special 301 Report on Intellectual Property Protection and Enforcement, and describing China’s predatory, non-market practices in its annual Report to Congress on China’s WTO Compliance.[29]

China’s IP protection system still lacks transparency and fair treatment for foreign actors in courts. It is inherently difficult to quantify potential bias against foreign-owned firms in China’s IP system due to limited transparency and weak accountability—in many cases, the quality and performance of China’s IP-related institutions cannot be independently verified.[30] China’s refusal to publish a complete record of relevant cases appears intended to impede independent analysis and monitoring of its implementation of IP-related commitments, including those under the POA and other bilateral and multilateral accords.[31]

China treats IP protection as a tool to advance its techno-economic objectives. For example, global anti-suit injunctions (ASIs) in China—which uniquely target foreign companies—help local companies to reduce the cost of foreign technology and patents in support of its industrial policy goals.[32] These ASIs aim to bar foreign courts from hearing disputes that could affect a Chinese court’s ability to set a global licensing rate for patented technologies. In many instances, they have been issued without notice to the affected party and without a subsequent publication, exacerbating already serious transparency concerns—and the Chinese law provides no effective mechanisms to challenge the courts’ assertion of jurisdiction.[33]

In addition, there exists a long history of inequitable patent-granting practices between domestic and foreign filers in China, and allegations that official data is biased because it omits unpublished cases.[34] While, on the surface, Chinese and foreign patent litigants in China have, on average, a similar win rate in court, there are clear differences in win rates regarding strategic technologies. For instance, between 2015 and 2019, foreign pharmaceutical patentees prevailed in only 36 percent of China Patent Reexamination Board (PRB) validity challenges, compared with 59 percent for Chinese applicants.[35] Similar gaps appear across other technology fields, including biotechnology (21 percent for foreign versus 48 percent for Chinese applicants) and environmental technologies (25 percent versus 40 percent, respectively).[36]

In addition to outlining existing evidence, this sub-section presents ITIF’s work on China’s economic espionage and on how Chinese digital platforms facilitate the entry of counterfeits into the U.S. market.

China Deploys Economic Espionage Campaigns Against the United States

In November 2025, ITIF’s report “From Outside Assaults to Insider Threats: Chinese Economic Espionage” outlined China’s campaign of economic espionage against the United States and American companies.[37] The report describes how China’s espionage ecosystem—from state intelligence agencies to nominally private firms—coordinated to steal U.S. industrial and defense technologies. This study highlights how Chinese companies (and academic researchers) operating in the United States serve as knowledge-collection platforms and how China turns engineers and researchers within U.S. firms into conduits for trade secrets.

Chinese actors have used a variety of methods to steal information from American companies.[38] As the report explains, “several Chinese economic espionage cases have involved the persistent penetrations of U.S. companies, rather than individuals’ illegally facilitated changes in career, which are uniquely damaging. They provide opportunities for PRC entities to remain current on developments within the U.S. industry rather than simply acquire increasingly stale stolen material.”[39] Another mechanism used by Chinese actors includes “breaking and entering” techniques, such as China’s use of academic institutions as cover for intelligence activities; active campaigns to hire individuals working for U.S. companies to transfer information from their private sector employers to Chinese entities; and using U.S.-based organizations to recruit expertise from which it then siphons trade secrets and other protected information.[40]

China Facilitates the Flow of Counterfeits Into the United States

As detailed in ITIF’s August 2025 report “How Chinese Online Marketplaces Fuel Counterfeits,” Chinese e-commerce platforms are a primary vector for counterfeit, unsafe, and IP-infringing goods entering the United States.[41] These platforms’ business models—and the industrial policy environment they operate in—fail to effectively enforce counterfeit sales by not adequately identifying and suspending probable counterfeits, allowing them to remain listed and accumulate significant sales. Coupled with China’s reluctance to pursue enforcement against counterfeiters serving foreign markets, this has created a pipeline through which counterfeit cosmetics, apparel, pharmaceuticals, and children’s products enter the United States at scale.[42]

This means that U.S. and other rights holders face widespread infringement with almost no recourse, while U.S. consumers are exposed to serious product safety hazards.[43] China’s government has failed to implement the Phase One IP commitments it made on enforcement against counterfeit goods, namely to “take effective action against e-commerce platforms that fail to take necessary measures against infringement” and to “significantly increase actions to stop the manufacture and distribution of counterfeits with significant health or safety risks.”[44]

China Continues to Force Technology Transfer on Foreign Investors

The POA did not change the direction or intention of the Chinese government’s treatment of foreign investors, as forced technology transfer remains a common practice in advanced industries investing in the Chinese market. USTR’s report “Four-Year Review of China Tech Transfer Section 301” already provides exhaustive evidence that Chinese forced technology transfer and pressures to force joint ventures with local companies persist after signing the POA.[45] This has also been reported by ITIF—in addition with the cases of technology transfer in the EV sector aforementioned.

For example, a 2022 ITIF testimony to the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission documented how China requires cloud-computing operations to be locally controlled.[46] As a result, providers such as Amazon Web Services and Microsoft must operate through Chinese partners, sell services under the Chinese partner’s brand, and share technology and operational know-how as part of these arrangements.[47] By contrast, Chinese cloud providers such as Aliyun—the cloud-services arm of Alibaba—are free to establish data centers in the United States without facing comparable ownership or technology-transfer requirements.

Policy Recommendations

ITIF will soon be releasing a major report that details a comprehensive policy response to China’s ongoing innovation mercantilisma and efforts to expand its global presenence in national power industries. Here, ITIF offers several policy recommendations pertinent to addresing China’s non-compliance with the POA.

The U.S. government should expand its authority to impose Section 301-related tariffs on Chinese goods that continue to benefit from the use of innovation mercantilist practices. USTR already has broad authority, under the ongoing Section 301 action on China’s technology-transfer and IP practices, to maintain and modify tariffs in response to China’s continued non-market behavior.[48] The current Section 301 investigation into China’s commitments under the POA would allow the U.S. government to impose a broader set of tariffs, including all the manufacturing products that are detailed in the agreement’s purchasing commitments. The scope of the current investigation should allow expanding the authority to impose tariffs on all Chinese imports beneffiting from unfair trade practices—which would be critical to improving the U.S. government’s negotiating position for future revisions to the trade deal with China.

Regarding controls on imports of Chinese goods benefitting from unfair trade practices, the U.S. government should seek to expand its authority through executive and Congressional action to:

▪ Ban importing goods from Chinese companies on the Entity List. Today, it is possible to purchase goods from the Chinese telecommunications company Huawei via resellers, including telecommunication equipment for private use, despite the company being listed in the Entity List since 2019. The presence of a company on the Entity List reflects the U.S. government’s view that it has been involved in activities contrary to the national security or foreign policy interests of the United States, and exporting goods or technologies to the company is restricted. USTR should close this loophole and fully ban these companies from the U.S. market.

▪ Ban all imports and U.S. presence of companies that have been involved in systematic or deliberate theft of American IP. While legislative action is needed to strengthen Section 337 of the Tariff Act—so the U.S. International Trade Commission (USITC) can more systematically exclude imports from China that benefit from unfair practices, including IP theft and other innovation mercantilist tools—the U.S. government already has other levers it can use against offending firms, such as anti-dumping and countervailing duty cases that raise tariffs on unfairly traded goods and, in appropriate circumstances, financial sanctions administered by the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control that can cut off access to U.S. dollar transactions. Where warranted, he U.S. government should explore using Section 301 authorities to impose broader import restrictions.

▪ Collaborate with like-minded allied nations to craft “a bill of particulars” that comprehensively enumerates China’s unfair trade practices impacting especially allied countries’ advanced industry sectors.[49]

▪ Expand efforts to forge a “Seven Eyes”-like alliance among key allies to exchange information about China’s industrial espionage activities impacting allied countries’ advanced industry sectors.

▪ Work with allied countries to have them implement Section 337-like legislation that would likewise permit them to wholesale block imports from Chinese companies that consistently use unfair trade practices.

▪ Use Section 301 authorities to enforce “immediate reciprocity.” USTR should consider using the 301 import control powers to address Chinese sectors that restrict or limit access for foreign competitors. A clear example of this is digital platforms for social media, where U.S. companies are barred from entering the Chinese market. If there are clear instances where U.S. firms are being wholesale blocked from competing in China’s market, then the United States should impose the same conditions on Chinese firms that would compete in the U.S. market.

▪ Utilize existing Treasury Department authorities to sanction Chinese companies benefitting from stolen IP or coerced technology transfer. Chinese firms that are stealing IP should be banned from accessing the U.S. banking and financial system.[50]

Additional policy measures for consideration.

▪ Ramp up efforts to limit Chinese cyber-IP theft and espionage. More needs to be done to limit Chinese IP theft. The next administration should work with Congress to pass legislation increasing criminal penalties for such actions. Its next budget should include a sizeable increase for the FBI’s Office of Commercial Counterintelligence.[51]

▪ Increase federal efforts to disrupt the global flow of counterfeits. Chinese counterfeit goods jeopardize U.S. consumer safety, erode public confidence, reduce U.S. jobs, and unfairly support Chinese economic growth. The government unfortunately struggles to stop many counterfeit shipments. To address this problem, the next administration should increase the Customs and Border Protection budget and appoint a director who will collaborate with private-sector stakeholders, including brand sellers, online marketplaces, and shippers, to establish real-time information sharing and analytics about potential counterfeit shipments that would allow them to better detect and seize more imported counterfeits.

▪ Increase criminal penalties for techno-economic espionage committed against U.S. firms. For too long, economic espionage has been treated as simply a commercial crime as opposed to a national security crime. With China laser focused on stealing as much core advanced technology information and knowledge as possible from the United States in order to gain global leadership and use in its civil-military fusion, it’s time for that to end.[52]

▪ Better prosecute trade crime, especially transshipment and misclassification. Chinese companies are masters at getting around trade rules, including exporting products to a country for transshipment to the United States as a way to circumvent U.S. tariffs. Often the amount of value added contributed in the third country is de minimis. Yet, this is seldom prosecuted. Congress should pass and fully fund the Protecting American Industry and International Trade Crimes Act that, among other elements, expands DOJ resources to prosecute trade crime.[53]

▪ Assess the impact of foreign unfair trade practices, especially China’s, on the long-term health of the U.S. industrial base. China’s mercantilist trade practices have contributed substantially to a hollowing out of the U.S. manufacturing base, including the U.S. defense industrial base. For this reason, ITIF supports the “America First Trade Policy’s” call for the secretaries of Commerce and Defense to “conduct a full economic and security review of the United States’ industrial and manufacturing base to assess whether it is necessary to initiate investigations to adjust imports that threaten the national security of the United States.”[54]

Thank you for your consideration.

Endnotes

[1]. Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR) and Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China, “Economic and Trade Agreement Between the Government of the United States of America and the Government of the People’s Republic of China” (Washington, DC and Beijing, January 15, 2020), https://ustr.gov/countries-regions/china-mongolia-taiwan/peoples-republic-china/phase-one-trade-agreement/text.

[2]. Karen M. Sutter, “Section 301 and China: The U.S.-China Phase One Trade Deal” (Congressional Research Service, updated February 12, 2025), https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/IF12125/.

[3]. Xi Jinping, “Speech by H.E. Xi Jinping President of the People’s Republic of China at the Welcoming Dinner Hosted by Local Governments and Friendly Organizations in the United States,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, September 22, 2015, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/eng/zy/jj/2015zt/xjpdmgjxgsfwbcxlhgcl70znxlfh/202406/t20240606_11381543.html.

[4]. CGTN, “No ‘forced technology transfer’ in China,” English.gov.cn, July 30, 2018, https://english.www.gov.cn/news/video/2018/07/30/content_281476242232166.htm.

[5]. Farah Master and Ryan Woo, “China tells US companies it will protect rights of foreign-funded firms,” Reuters, April 7, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/business/china-tells-us-companies-it-will-always-provide-protection-foreign-funded-firms-2025-04-07/.

[6]. Stephen Ezell, “False Promises II: The Continuing Gap Between China’s WTO Commitments and Its Practices” (ITIF, July 26, 2021), https://itif.org/publications/2021/07/26/false-promises-ii-continuing-gap-between-chinas-wto-commitments-and-its/.

[7]. Emily Jin, “A Policymaker’s Guide to China’s Technology Security Strategy” (ITIF, February 18, 2025), https://itif.org/publications/2025/11/17/marshaling-national-power-industries-to-preserve-us-strength-and-thwart-china/.

[8]. Ibid.

[9]. Ibid.

[10]. Stephen Ezell, “Don’t Let Chinese EV Makers Manufacture in the United States” (ITIF, September 17, 2025), https://itif.org/publications/2025/02/18/a-policymakers-guide-to-chinas-technology-security-strategy/.

[11]. Ibid.

[12]. Ibid.

[13]. Ezell, “Don’t Let Chinese EV Makers Manufacture in the United States”; Keith Bradsher, “Hybrid in a Trade Squeeze,” The New York Times, September 5, 2011, https://www.nytimes.com/2011/09/06/business/global/gm-aims-the-volt-at-china-but-chinese-want-its-secrets.html.

[14]. Ezell, “Don’t Let Chinese EV Makers Manufacture in the United States.”

[15]. Ibid.

[16]. Alex Rubin, “China Plans to Dominate a Key Semiconductor Material” (ITIF, September 8, 2025), https://itif.org/publications/2025/09/08/china-plans-to-dominate-a-key-semiconductor-material/.

[17]. Ibid.

[18]. Rubin, “China Plans to Dominate a Key Semiconductor Material;” Compiled from publicly available information sourced from Bernreuter Research, Bloomberg, Wood Mackenzie, SEIA, Global Trade Tracker, and NREL.

[19]. Rodrigo Balbontin, “Backfire: How Export Controls Helped Huawei and Hurt U.S. Firms” (ITIF, October 27, 2025), https://itif.org/publications/2025/10/27/backfire-export-controls-helped-huawei-and-hurt-us-firms/.

[20]. Eli Clemens, “China’s State-Backed E-Commerce Platforms Threaten American Consumers and U.S. Technology Leadership” (ITIF, April 2, 2025), https://itif.org/publications/2025/04/02/chinas-state-backed-e-commerce-platforms-threaten-american-consumers-us-technology-leadership/.

[21]. Federal Trade Commission, “Online Marketplace TEMU to Pay $2 Million Penalty for Alleged INFORM Act Violations,” news release, September 2025, https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2025/09/online-marketplace-temu-pay-2-million-penalty-alleged-inform-act-violations.

[22]. Karen M. Sutter, “Section 301 and China: The U.S.-China Phase One Trade Deal” (Congressional Research Service, updated February 12, 2025), https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/IF12125.

[23]. U.S. Department of the Treasury, “Macroeconomic and Foreign Exchange Policies of Major Trading Partners of the United States” (Washington, DC, June 2024), https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/June-2024-FX-Report.pdf.

[24]. USTR, “Economic and Trade Agreement Between the Government of the United States of America and the Government of the People’s Republic of China.”

[25]. Ibid.

[26]. Chad P. Brown, “The US–China trade war and Phase One agreement,” Journal of Policy Modeling 43, No. 4 (July-August 2021): 805–843., https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0161893821000363; U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, “Challenging China’s Trade Practices” (Washington, DC, November 2022), https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/2022-11/Chapter_2_Section_2--Challenging_Chinas_Trade_Practices.pdf.

[27]. Peterson Institute for International Economics, “U.S.–China Phase One Tracker: China’s Purchases of U.S. Goods,” PIIE Charts, accessed April 30, 2025, https://www.piie.com/research/piie-charts/us-china-phase-one-tracker-chinas-purchases-us-goods.

[28]. USTR, “Economic and Trade Agreement Between the United States of America and the People’s Republic of China Fact Sheet” (Washington, DC, January 15, 2020), https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/files/agreements/phase%20one%20agreement/US_China_Agreement_Fact_Sheet.pdf.

[29]. Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR), “USTR Releases 2024 Review of Notorious Markets for Counterfeiting and Piracy,” press release, January 8, 2025, https://ustr.gov/about/policy-offices/press-office/ustr-archives/2007-2024-press-releases/ustr-releases-2024-review-notorious-markets-counterfeiting-and-piracy.

[30]. Mark A. Cohen, written testimony before the Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Subcommittee on Intellectual Property, Foreign Threats to American Innovation and Economic Leadership, May 14, 2025, https://www.judiciary.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/2025-05-14_testimony_cohen.pdf.

[31]. Ibid.

[32]. Mark Cohen, interview by Victoria Huang, “U.S.-China Intellectual Property Issues in a Post-Phase-One Era,” (National Bureau of Asian Research, January 29, 2022), https://www.nbr.org/publication/u-s-china-intellectual-property-issues-in-a-post-phase-one-era/.

[33]. Ibid.

[34]. Mark Cohen, “Are Chinese Courts Out to ‘Nab’ Western Technology: An Inconclusive WSJ Article,” China IPR – Intellectual Property Developments in China (blog), February 24, 2023, https://chinaipr.com/2023/02/24/are-chinese-courts-out-to-nab-western-technology-an-inconclusive-wsj-article/.

[35]. Ibid.

[36]. Ibid.

[37]. Darren E. Tromblay, “From Outside Assaults to Insider Threats: Chinese Economic Espionage” (ITIF, November 3, 2025), https://itif.org/publications/2025/11/03/from-outside-assaults-to-insider-threats-chinese-economic-espionage/.

[38]. Ibid.

[39]. Ibid.

[40]. Ibid.

[41]. Eli Clemens, “How Chinese Online Marketplaces Fuel Counterfeits” (ITIF, August 2025), https://itif.org/publications/2025/08/20/how-chinese-online-marketplaces-fuel-counterfeits/.

[42]. Eli Clemens, “Comments to the United States Patent and Trademark Office Regarding Countering Illicit Trade” (ITIF, June 25, 2025), https://itif.org/publications/2025/06/25/comments-united-states-patent-trademark-office-regarding-countering-illicit-trade/.

[43]. Eli Clemens, “How Policymakers Can Stop Chinese Copycat Commerce” (ITIF, June 2025), https://itif.org/publications/2025/06/11/how-policymakers-can-stop-chinese-copycat-commerce/; Eli Clemens, “Strengthening Product Safety Enforcement on Chinese E-commerce Platforms” (ITIF, April 2025), https://itif.org/publications/2025/04/15/strengthening-product-safety-enforcement-on-chinese-e-commerce-platforms/.

[44]. USTR, “Economic and Trade Agreement Between the Government of the United States of America and the Government of the People’s Republic of China.”

[45]. USTR, “Four-Year Review of Actions Taken in the Section 301 Investigation: China’s Acts, Policies, and Practices Related to Technology Transfer, Intellectual Property, and Innovation” (Washington, DC, May 14, 2024), https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/USTR%20Report%20Four%20Year%20Review%20of%20China%20Tech%20Transfer%20Section%20301.pdf.

[46]. Stephen Ezell, “Testimony Before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission on “U.S.-China Innovation, Technology, and Intellectual Property Concerns” (ITIF, April 14, 2022), https://www2.itif.org/2022-us-china-innovation-tech-ip.pdf.

[47]. Ibid.

[48]. Sandler, Travis & Rosenberg, P.A., “Section 301 Tariffs on China,” https://www.strtrade.com/trade-news-resources/tariff-actions-resources/section-301-tariffs-on-china.

[49]. Robert D. Atkinson, Nigel Cory, and Stephen Ezell, “Stopping China’s Mercantilism: A Doctrine of Constructive, Alliance-Backed Confrontation” (ITIF, March 2017), https://www2.itif.org/2017-stopping-china-mercantilism.pdf.

[50]. Stephen Ezell, “Tariffs Won’t Stop China’s Mercantilism. Here Are 10 Alternatives,” Real Clear Politics, April 23, 2018, https://www.realclearpolicy.com/articles/2018/04/23/tariffs_wont_stop_chinas_mercantilism_here_are_10_alternatives_110605.html.

[51]. Tromblay, “Protecting Partners or Preserving Fiefdoms? How to Reform Counterintelligence Outreach to Industry.”

[52]. Robert D. Atkinson and Stephen Ezell, “Toward Globalization 2.0: A New Trade Policy Framework for Advanced-Industry Leadership and National Power” (ITIF, March 2025), https://itif.org/publications/2025/03/24/globalization2-a-new-trade-policy-framework/.

[53]. The Select Committee on the CCP, “Protecting American Industry from International Trade Crimes Act Passes House” (December 2024), https://selectcommitteeontheccp.house.gov/media/bills/protecting-american-industry-international-trade-crimes-act-passes-house.

[54]. The White House, “America First Trade Policy,” memorandum to agency heads, January 20, 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/america-first-trade-policy/.