Forget GDP. The Real Reason to Boost Manufacturing Is Power

President Trump and many supporters of boosting U.S. manufacturing argue that doing so will grow the economy and make Americans better off. Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick recently stated, “Remember when Donald Trump says we’ve got $5 trillion of factories coming to America. Think of 5 trillion divided by his four years. That is huge GDP growth.”

Not quite. In reality, Trump’s policies would make Americans worse off in the short term, though potentially better off in the long run. Unless the new manufacturing output is higher value-added than the average GDP, it won’t move the GDP needle.

The reasons are simple. First, the U.S. economy is at full employment. Increasing factory output, presumably by reducing imports or expanding exports, means that workers filling these new jobs must come from other sectors, where output will have to decline.

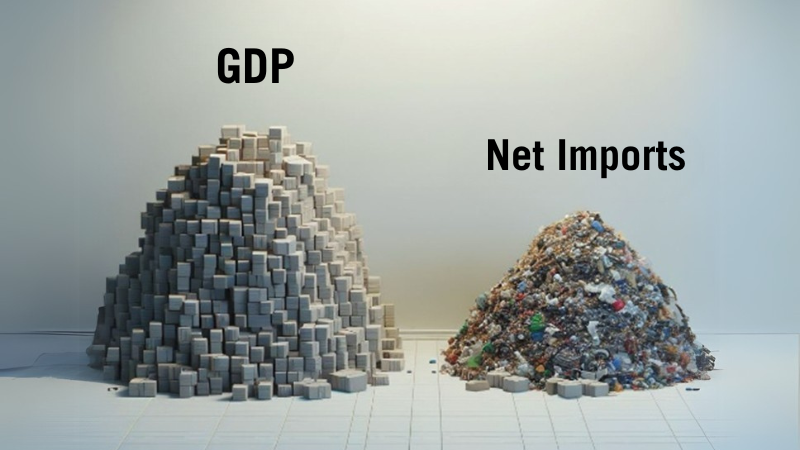

This concept can be hard to grasp in part because the discipline of economics tends to focus on numbers and models rather than the real economy. Figure on the right showing GDP and net imports represents the real economy. GDP is nothing but the whole heap of goods and services we produce each year—think of the annual accumulation of cars assembled, haircuts given, houses built, bank transactions completed, and think tank papers written (especially the last).

The size of that GDP pile is determined by two factors: the number of workers and how much they produce per hour of work (i.e., productivity). So, bringing more manufacturing to the United States will, by definition, mean shifting some workers from non-manufacturing sectors (maybe all of Musk’s laid-off government workers?) into manufacturing roles, since the total number of workers will stay the same.

This could boost GDP if the new manufacturing jobs are more productive than the jobs workers leave. While manufacturing productivity was once significantly higher than that of non-manufacturing sectors, its growth has stagnated over the past 15 years. As a result, manufacturing productivity is now just 4 percent higher than the economy-wide productivity average. And given that manufacturing accounts for less than 10 percent of U.S. employment, adding manufacturing jobs would do relatively little to boost per-capita income.

Moreover, there’s a second-order effect. To boost manufacturing, the United States would need to reduce its massive $1 trillion trade deficit. A key way to do that is by changing the relative after-tax cost of imports and exports. Trump is trying to accomplish this through sweeping import tariffs. The problem? Other countries will likely retaliate with tariffs of their own—yielding no net advantage for U.S. exports.

Another option is to drive down the value of the dollar, which would make imports more expensive and exports more competitive (cheaper). But the Trump administration appears committed to the long-standing and misguided policy of defending an overvalued dollar. A third, more effective strategy would be to introduce a border-adjustable value-added tax, something many other nations already have, that raises the price of imports without triggering retaliation.

As noted, none of this would boost GDP significantly, because manufacturing productivity is now close to overall productivity. It would, however, reduce the trade deficit. And while closing the trade deficit wouldn’t change GDP, it would reduce domestic consumption.

Consumption is the sum of both piles pictured in the figure above: what we produce domestically (GDP) and what goods and services we import in excess of what we export (net imports). Relative to most countries, American consumers are living the good life—they consume more than they produce. In fact, they consume about $1 trillion more each year in imports: cars, wine, furniture, you name it. And for now, they get it essentially for free. Other nations are giving us these goods in exchange for IOUs, hoping we’ll pay them back someday with real goods and services, just as a bank lends you money for a mortgage. The U.S. trade deficit is, in effect, a loan.

If Trump succeeds, American consumption will actually decline, as the pile of net imports in the figure shrinks toward zero. So why pursue this? Because we should care about our children. As Herb Stein once quipped, “If something can’t go on forever, it won’t”—and the trade deficit can’t go on forever. Sooner or later, Americans will have to produce more than they consume and send the excess to countries that have long-run trade surpluses with us. The longer we delay, the more trade debt we pass on to the next generation.

Given all that, why focus on manufacturing? The reason should not be jobs or GDP. The first reason should be to reduce the trade debt we’re leaving to our children. But no politician, including Trump, will be able to sell manufacturing policy that way.

Imagine this pitch to voters: “I want you selfish Americans to consume less—oh, and also pay more in taxes and get fewer government services—to pay down the national debt so your kids and their kids won’t be burdened with the bill you losers racked up.” Yeah… That’ll go over well, right?

No, because Americans are selfish! They’d boot that candidate out of office in a heartbeat. So, while I get the narrative about jobs and GDP growth, if we’re being honest (and right now, we’re being honest), that’s not the real reason.

The second and most important reason to focus on manufacturing is national power. A deindustrialized nation, which the United States is on the path to becoming, is not a strong nation.

Especially not when China is doing everything it can to dominate the world’s advanced, dual-use industries, such as machinery, transportation equipment, computers, semiconductors, electrical equipment, biopharmaceuticals, and more. If America continues to lose global market share in these sectors, China will have us by the proverbial balls—and all we’ll be able to say is “Yes, President Xi.”

So, what does that mean? It means U.S. manufacturing policy should focus on restoring strategic industrial strength rather than growing all manufacturing for specious reasons, such as job creation. That also means ignoring both camps of Trump trade advisers: the economic nationalists like Peter Navarro and Michael Stumo, and the free-market fundamentalists. They all buy into the line, “Potato chips, computer chips, what’s the difference?” We need an administration that’s laser-focused on rebuilding capacity in advanced industries (in other words, computer chips—and by the way, tariffs on those will backfire and lead to less U.S. semiconductor production).

One last note: The goal should be production capabilities and output, not jobs. This is not social policy; it is national defense and national power policy. On that front, Secretary Lutnick is absolutely right when he talks about robotic factories in the United States. Congress and the administration should set a bold goal of having the most automated and roboticized factories for advanced industries in the world. Forget job creation—think capability creation.

Maybe it’s time to be honest with voters and try this pitch: “You’ll need to sacrifice a little—yes, that means consuming less and paying more in taxes—so your kids won’t inherit the consequences of our trade and budget deficits, and so America doesn’t become a vassal state to China.” Yeah… That sounds like a fair trade, doesn’t it?

Editors’ Recommendations

Related

June 6, 2025

No, American Manufacturing Hasn’t Been Revived

January 27, 2025