Canadian Businesses Are Not Profiteering

The cost of living has increased significantly in Canada and most of the Western world in the last few years, but Canadians pointing their fingers at “profit-hungry price gouging” should look elsewhere. While it makes for a comforting narrative, claims that big companies have recently been profiteering during times of rising inflation and that we need to inject greater competition in these sectors to fix the issue are more based on feeling than fact. This matters because Canada already suffers from a surfeit of large firms with adequate scale for effective productivity and competitiveness. Feeding the anti-corporate, more competition narrative will just make that worse.

A comparison of net profit margins (a measure of how much money a company makes as a percentage of its revenue after factoring in all costs, including interests and taxes) shows that big Canadian telcos, grocery stores, and banks have not seen major changes in profitability over the past four years, or compared to their peers in other countries. The data suggests that rising prices should not be attributed to avarice and rent-seeking but rather plain old inflation.

Comparing the average net profit margins of large Canadian firms to those in the same sectors in other countries allows for a holistic look at whether companies are increasing the prices of their goods and services to address rising costs or simply to make more profit in the absence of enough competition to discipline them. Net margins are used here rather than gross margins as they indicate operational efficiency, not just production efficiency. Net margins are also easier to standardize across international comparisons due to differing interest and tax regimes that might affect pricing decisions and profitability.

The figures below examine the net profit margins of large Canadian firms, averaged from financial data of publicly traded companies, in the telecommunications services, grocery retail, and money centre banking sectors, and compare them to large firms in the United States, Western Europe, and Japan (a country that did not experience the same wave of inflation after COVID-19 that Western nations faced).[1]

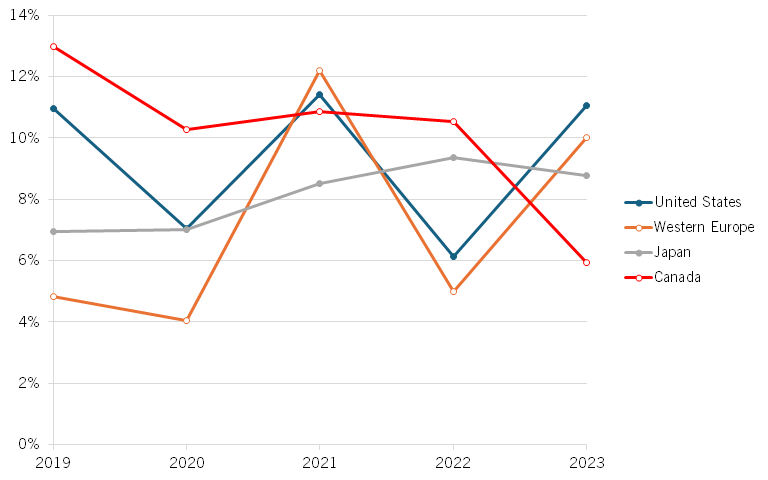

Figure 1: Net profit margins, major telecommunications services

The three major Canadian telecommunications service companies (Bell, Rogers, and Telus) have not increased their net profit margins in the last four years. In fact, they have seen their net margins decrease by more than half, going in the opposite direction to that of their international comparators.

Indeed, Statistics Canada’s consumer price index has shown that quality-controlled wireless prices have decreased by almost 50 percent between 2019 and 2024, driven by both innovation and competition in the telecom sector with competing promotions and more generous data plans. In an industry with intense infrastructure requirements driven heavily by economies of scale, further competition would likely lead to higher costs and, therefore, higher prices for Canadians. Even if telecommunications profits were zero, the prices Canadians see on their bills would decrease by a few dollars a year while millions would need to be spent on building extraneous infrastructure.

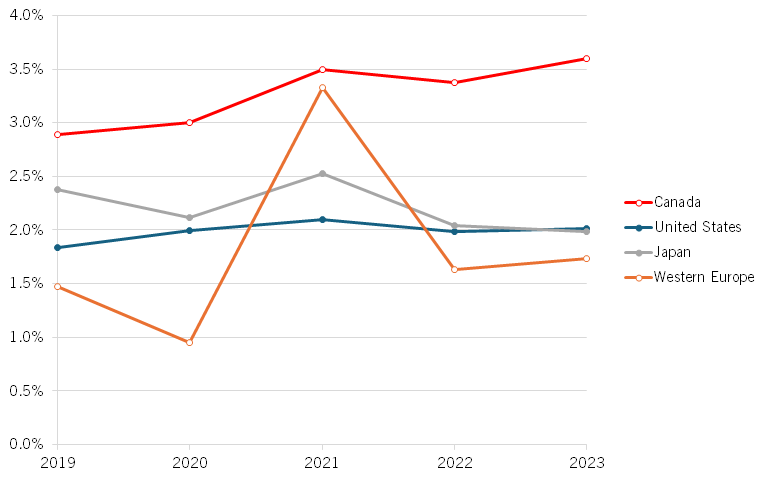

Figure 2: Net profit margins, major grocery retailers

Canada’s largest grocery retailers (Empire, Loblaws, and Metro) have seen a roughly 1.5 percent higher net margin than their peers in other countries. Additionally, Canada's grocery retailers have experienced a slightly higher growth of profit margins than their international counterparts from 2019 to 2023.

According to the 2024 Canada Food Price Report, a Canadian family comprised of two middle-aged parents, a teenage boy, and a preadolescent girl spent $15,595 on food in 2023. After accounting for the 43 percent of their food budget that Canadians spent on average in restaurants in 2023, the average Canadian family paid $8,889 at grocery stores. If Canadian grocery retailers decreased their revenues in order to decrease their net margins of 3.59 percent to match the 1.99 percent that their counterparts in Japan had, the average Canadian family would see a $174 decrease in their grocery bill per year. While $174 is nothing to scoff at, it does not even register as a dent in how much consumer spending has increased in the last few years.

Moreover, as noted by the Competition Bureau, this increase in grocery profit margins could be explained by a shift in consumer preferences towards private-label products (e.g., Kirkland frozen lasagna at Costco versus name-brand frozen lasagna), which tend to be lower cost than their name brand counterparts but have higher profit margins for the store itself.

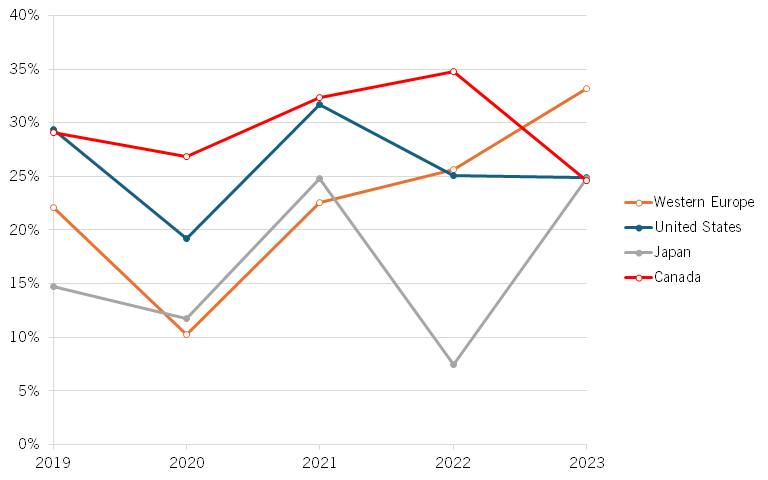

Figure 3: Net profit margins, major money centre banks

Lastly, net margins for major money centre banks in Canada (BMO, Scotiabank, CIBC, RBC, National Bank, and TD) have actually decreased slightly between 2019 and 2023. They are roughly equal to bank profits in the United States and Japan and are lower than those in Western Europe.

Critics say that if only we had more competition, like in the United States or the European Union, then prices would be lower in Canada. There are two mechanisms in which more competition could decrease prices, both reflected in net profit margin comparisons, and neither holds true in Canada right now. The first is that big Canadian companies run lazy and inefficient operations, and more competition would kick them into gear when deciding to compete. It is unlikely that publicly traded companies with shareholders demanding high returns in Canada would keep their CEOs around if they were racking up excess costs and wasting money.

The second way in which more competition might decrease prices would be a reduction in revenues. Competition advocates argue that these Canadian firms face too little competition and, therefore, set their prices high accordingly. Yet, as the data above shows, Canada’s profitability is roughly the same, if not lower, than its international peers. So, what should Canada do if neither the revenues nor the costs reflect a situation where greater competition would remedy higher prices?

As a relatively small economy, Canada simply cannot afford low levels of industry concentration and atomistic industry structures because that prevents firms from achieving the economies of scale they need. This is why if the average firm size in Canada matched that of the United States, the average Canadian per-capita annual income would see an increase of $2,430. That would pay annual grocery costs and more.

The economic headwinds that the country faces are too great to fall into the anti-corporate, antitrust fervor. Encouraging greater scale would go a long way toward remedying the ailing productivity of Canadian firms and creating better conditions for Canadian consumers.

Endnotes

[1] Data compiled from the disclosed net profit margins of large, publicly traded companies derived from https://www.google.com/finance/, and from financial data compiled by New York University Professor Aswath Damodaran’s website: https://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~adamodar/New_Home_Page/datacurrent.html#cashflows.