How ‘Schrems II’ Has Accelerated Europe’s Slide Toward a De Facto Data Localization Regime

A year after the Court of Justice of the European Union’s (CJEU’s) Schrems II decision to invalidate the EU-U.S. Privacy Shield, U.S. and other foreign firms and trading partners face an uncertain and increasingly onerous legal environment. The transatlantic digital relationship is in a perilous position. Without a successor agreement, there can’t be any realistic platform for broader cooperation on data, the digital economy, and emerging technologies via the new EU-U.S. Trade and Technology Council. While negotiations for a successful agreement continue, statements and decisions by individual EU data protection authorities and European officials show that absent a political push for a new agreement, the EU will continue sliding toward data localization and digital protectionism.

Transfers of personal and non-personal data are not an optional input in modern trade and commerce—they are central. ITIF’s reports on the invalidation of the EU-U.S. Privacy Shield, the role and value of standard contractual clauses in EU-U.S. digital trade, and the importance of the transatlantic data relationship show that the shockwaves from the Schrems II ruling and ongoing decisions around data transfers extended well beyond traditional “tech” firms and services to manufacturing and health research, from big firms to startups and small and medium-sized firms.

European officials have provided limited clarity about what exactly firms need to do post-Schrems II. The European Commission (EC) and European Data Protection Board’s (EDPB) advice has been more about articulating how to lock in its onerous and restrictive requirements that make data flows harder (especially for small and medium-sized firms) rather than providing clear, accessible, and predictable legal tools to actually support transfers of EU data abroad.

Ultimately, a year after the Schrems II decision, U.S. firms find themselves in a very tough position: they have a restricted range of legal compliance options to transfer personal data from the EU; they face growing EU member state-specific enforcement risks; they face audits of their data transfers to identify those that touch America; and they face a growing number of European authorities advising users to not use cloud-based software in the United States, and in some cases, even U.S. services hosted in the EU.

The cases below are indicative of what the one-year anniversary shows, including that:

- Schrems II removed or raised uncertainty about popular legal tools

- Schrems II is turning the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) into the world’s largest de facto data localization framework

- Schrems II risks standard passenger screening for terrorists

- Schrems II highlights the impact of data protection authorities being able to assume anything and the impact of not doing any sort of risk assessment of surveillance

- EU institutions send a clear signal that U.S. service providers are not trusted

- Schrems II empowers individual (activist) data protection authorities to target any data service that touches the United States

- Schrems II’s impact will be broad and continue to ripple for some time

- Schrems II reveals that data localization may not be enough—it’s about data sovereignty

- Schrems II undermines critical transatlantic health research

- Cutting off data flows entails significant economic costs to Europe

Schrems II Removed or Raised Uncertainty About Popular Legal Tools

U.S. and European firms continue to face uncertainties that could undermine their operations and significantly raise the cost of maintaining compliance with restrictions that continue to change. The thousands of firms that used Privacy Shield are no doubt still figuring out how to adapt so as to continue transferring data between the United States and EU. Most are turning to, or leaning more heavily on, standard contractual clauses (SCCs), but these also carry uncertainties as well as additional costs:

- In a survey conducted by law firm Fieldfisher in the months following the Schrems II decision, one-third of respondents had not yet decided whether they would reduce the use of non-EU data processors, and 12 percent indicated they had already chosen to do so.

- An October 2020 survey from McKinsey found that while 55 percent of companies were doing something to implement additional safeguards, 47 percent noted they were not sure they could guarantee sufficient data protection.

- Finally, a report from a coalition of European industry associations estimated that 85 percent of the firms surveyed used SCCs, and while only about half reassessed their use of SCCs in the wake of the Schrems II decision, 92 percent of those that did consider the cost of doing so to be moderate or high.

Survey Shows Schrems II is Turning GDPR into the World’s Largest De Facto Data Localization Framework

An April 2021 report by the Cross-Border Data Forum showed that data localization was a prominent theme among the nearly 200 comments submitted to the EDPB in response to its November 2020 draft guidance about transferring personal data from the EU to third countries. A review of all the comments showed that approximately 25 percent of all comments expressed concern that the draft guidance would result, in practice, in data localization and that slightly more than 10 percent of the comments spoke explicitly about how it would result in data localization, in law, in practice, or both.

Schrems II Risks Standard Passenger Screening for Terrorists

Schrems II risks undermining “passenger name records” (PNR) sharing agreements that ensure personal information on passengers on international flights can be shared so that authorities can screen for terrorists. It is clearly in both the U.S. and Europe’s interest to share this information. It also highlights how absurd privacy fundamentalists’ calls to cut off data flows are when it involves sensible, mutually beneficial uses. There have been multiple PNR sharing agreements between the U.S. and EU since the 9/11 attacks, with this being the fourth time the CJEU or European Parliament has decided these agreements violate EU privacy laws. The European Commission is studying how to bring the U.S.-EU PNR Agreement into line with Schrems II. The United States has stated that it’s unwilling to budge on PNR security measures.

Schrems II Highlights the Impact of Data Protection Authorities Being Able to Assume Anything and of Not Conducting a Risk Assessment of Surveillance

Portugal’s data protection authority (DPA), citing Schrems II, directed Portugal’s National Institute of Statistics (INE) to suspend or prohibit data transfers to a U.S. cloud provider (Cloudflare) it wanted to use for a national census project. Despite the fact INE wanted to use EU standard contractual clauses, the DPA still wanted to prevent data transfers as the cloud provider is directly subject (without any evidence or data) to potential U.S. surveillance.

This gets to the broader point about how misguided the EDPB’s suggestion is that the likelihood of government access should not be considered, and data should not be transferred if it is even just hypothetically subject to surveillance. Reasonable and responsible policy should be based on a sensible sense of risk. Given how many countries engage in electronic surveillance, taken to its logical conclusion, this approach would essentially preclude the use of any digital devices or services. But this is just one reason why policy should not be based on a zero-risk approach. Thankfully, the European Commission issued draft new standard contractual clauses that adopted some of the EDPB’s recommendations, but not all, favoring a pragmatic, risk-based approach to implementation.

EU Institutions Send a Clear Signal that U.S. Service Providers are Not Trusted

European officials have sent a clear signal to DPAs and others in Europe that foreign, especially U.S., digital services providers are not to be trusted in instructing European public institutions to not use U.S. service providers. At the end of May 2021, the European Data Protection Supervisor (which overseas EU institutions) launched two investigations regarding the use of U.S. cloud service providers. One focuses on the EU institution’s use of Amazon Web Services and Microsoft, and another on the European Commission’s use of Microsoft Office 365. These investigations stem from the EDPS’ October 2020 inquiry into EU institutions’ data transfers to non-EU countries, which showed that many relied on U.S. cloud-based software and cloud infrastructure.

Schrems II Empowers Individual (Activist) Data Protection Authorities to Target Any Data Service that Touches the United States

Individual European DPAs are entitled under GDPR to take their own enforcement action, including binding orders to cease cross-border data transfers and impose high fines. Over the last year, their individual decisions add up and show a strong underlying preference for data localization.

Germany’s state-level DPAs are among the most ardent supporters of cutting off data transfers to the United States. German DPAs are taking joint action to enforce Schrems II, including a multi-state audit process to examine data transfers. DPAs in the German states of Hamburg and Baden-Württemberg have already threatened companies transferring data to the United States that if they do not take certain measures, they may be at a “material risk” of fines.

Microsoft represents a prominent example, although it’s just one of the many U.S. ICT services companies whose communication and collaboration tools are under fire in Europe. Hamburg’s DPA sent out a questionnaire asking how companies manage data transfers while using Microsoft 365. Prior to this, in October 2020, German data protection authorities determined that Microsoft Office 365 does not comply with European data privacy laws. Since then, Microsoft has invested substantially in trying to meet Europe’s ever-changing and restrictive requirements via new standard contractual clauses. This follows the eye-opening lack of risk analysis exhibited by the DPA of the German state Hasse in its 2019 decision to prohibit schools from using Microsoft due to “possible access by U.S. officials.”

Similarly, Swedish government agencies ruled that public authorities must use Skype (which is owned by Microsoft) rather than Microsoft Teams’ cloud-based service as they think that Teams discloses too much data to Microsoft and puts it at risk of U.S. government surveillance. Likewise, France’s DPA, CNIL, issued a public announcement in May 2021 directed at higher education and research institutions, calling for them to stop using collaborative tools offered by U.S. firms.

Likewise, DPAs have targeted the use of common digital marketing tools. On March 15, 2021, the Bavarian DPA decided that a German publishing company should stop using the online service Mailchimp (a common marketing automation platform and email marketing service) after receiving a complaint from an individual. It’s the first German enforcement action in connection to Schrems II. The DPA determined that the transfer of the complainant's email address to the Mailchimp platform was unlawful because the publishing company had not examined whether, in addition to SCCs, supplementary measures within the meaning of the CJEU’s decision were necessary to ensure that the transfer met the GDPR requirements. All of this based off the concern from an individual and a determination that Mailchimp might qualify as an electronic communication service provider under U.S. surveillance law (FISA 702).

The U.S. equivalent would be accusing German multinational software company SAP as being a hypothetical tool for surveillance and trade secret theft just because it is German, subject to German surveillance laws, and used by firms across the United States.

Schrems II’s Impact Will Be Broad and Continue to Ripple for Some Time

The EDPB established a task force after Max Schrem’s advocacy organization NYOB sent 101 identical complaints regarding processing services provided by Google/Facebook that previously relied on Privacy Shield and SCCs. The task force will determine how these systems should operate now that Schrems II has invalidated their previous structure for legal transfers.

Schrems II Reveals that Data Localization May Not be Enough—It’s About Data Sovereignty

GDPR and Schrems II are convincing more and more companies to localize their data storage and processing in the EU given the lack of legal mechanisms to transfer data overseas, the uncertainty about overseas transfers, and the potential for large fines from activist DPAs. However, the last year has shown how concerns about data privacy in Europe are being subsumed by the overarching drive for “data sovereignty.” Recent decisions, announcements, and court cases in the last year show that European officials, especially in France, do not think that data localization provides adequate protection from foreign government access requests and that local data needs to be controlled by a local firm. This highlights Europe’s attraction to protectionist-based digital industrial development policy.

In October 2020, France’s DPA issued recommendations for French services handling health data that they avoid using American cloud services entirely (even if they manage and process this data in Europe). In addition, French courts had to step in on two separate cases that not only sought to cut off data flows to the United States, but exclude U.S. firms from managing the data overall. In one case, AWS hosting was used for a covid vaccine registration site, thus sending personal health data to AWS servers. After reviewing a complaint that this violated GDPR, a French court found that satisfactory encryption keys were used to block any potential AWS access, and suspension was not warranted.

In 2020, Microsoft’s central role in a French government initiative to create a new “Health Data Hub” (HDH) was challenged. Local government officials, firms, and public advocacy groups voiced support for a local provider, with some launching a legal challenge to suspend the HDH (which was rejected by France’s highest administrative court). Indicative of their support for not just data localization but local control, CNIL submitted comments to the court advocating that it not only consider Schrems II, but that it also consider the lawfulness of processing in the EU by companies subject to U.S. laws. Thankfully, the court determined that EU law does not prohibit the use of U.S. service providers to process data on EU soil.

In May 2021, CNIL’s public announcement to higher education and research institutions for them to stop using collaborative tools offered by U.S. firms noted how this was important to support the EU’s digital sovereignty.

Schrems II Undermines Critical Transatlantic Health Research

Schrems II’s impact on transatlantic data flows undermines critical health research, which is increasingly dependent on the collection, aggregation, and analysis of data for drug discoveries and other health treatments.

A joint report by three academic networks (the European Federation of Academies of Sciences and Humanities, the European Academies’ Science Advisory Council, and the Federation of European Academies of Medicine) estimates that over 5,000 international health projects were negatively affected by confusion over how to properly transfer personal data cross-border following Schrems II. These researchers highlight how modern medical research, such as Alzheimer’s, relies on massive data pools.

Researchers at University College Dublin, for example, had to split one research study into two separate parts, one within the EU and one outside the EU, to comply with GDPR standards. While the researchers could conduct their study and comply with GDPR, the modifications “may increase costs, affect statistical analysis and sample size, and increase the possibility of inaccuracy.”

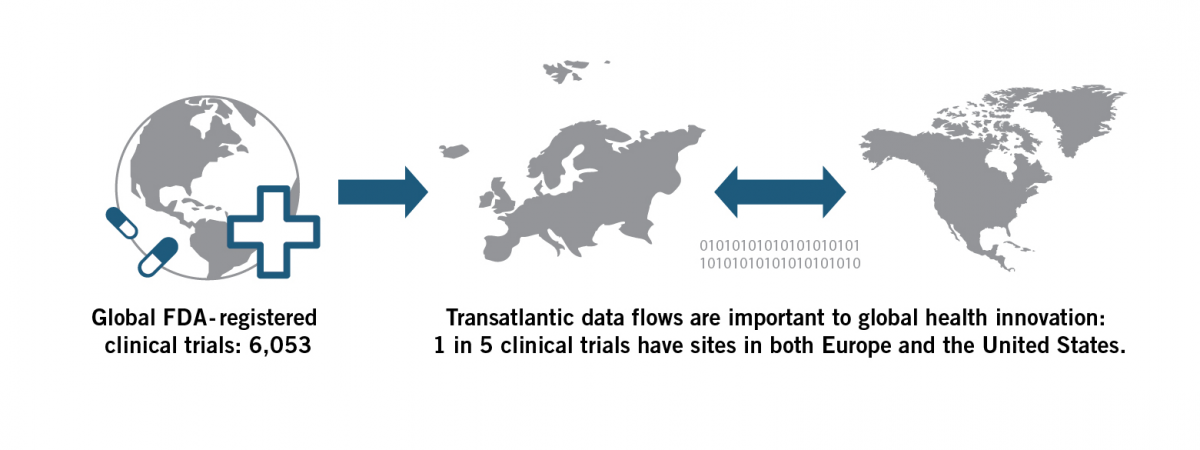

Health researchers were already grappling with challenges to data-sharing practices caused by GDPR before Schrems II. Without Privacy Shield or clear and accessible SCCs, the viability of critical transatlantic health research remains uncertain. The case on health services in ITIF’s report How to Build Back Better the Transatlantic Data Relationship shows what is at risk. For example, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) clinical trials database showed that of all clinical trials registered, 39 percent had a clinical trial in at least one European country, while 22 percent had clinical trials on both sides of the Atlantic (figure 1).

Figure 1: Health data transfers are critical to the many FDA-registered clinical trials in both the United States and European Economic Area

Cutting off Data Flows Causes Significant Economic Costs for Europe

A (2021) Digital Europe econometric study (the Value of Cross-Border Data Flows to Europe: Risks and Opportunities) of the scenario if GDPR did not allow firms to transfer data found that it would reduce EU exports by around 4 percent and reduce GDPR by around 1 percent annually. Cumulatively to 2030, losses amount to $1.5 trillion. The loss in output corresponds to around 1.3 million jobs in the impacted sectors. By contrast, if the EU and major trade partners adopted measures to facilitate cross-border data transfers, EU exports as a whole would grow by a little over 2 percent per year, adding 0.6 percent to GDP per year, which is around 0.7 million jobs in the impacted sectors. Cumulative effects to 2030 are worth around $852 billion.

Digital Relations at a Crossroads: Transatlantic Cooperation or European Data Sovereignty?

What hasn’t changed in the last year is the need for governments to step in and negotiate an agreement as firms aren’t able to resolve the underlying issue regarding government access to data. The central issue in negotiations is how to address the issue around independent oversight and redress in the U.S. system for European citizens who suspect they were surveilled by the National Security Agency.

Thankfully, key U.S. and EU political leaders recognize what is at stake and support ongoing negotiations to develop a successor agreement, one that will hopefully be sustainable in the long term. U.S. President Biden, U.S. Department of Commerce Secretary Raimondo, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, European Union Justice Commissioner Didier Reynders, and others have provided much-needed political support for a new transatlantic digital bridging mechanism. Their support is critical to countering European officials and agencies who support cutting off data flows and digital trade with the United States. Some European officials remain completely unwilling to see any fault in GDPR and summarily dismiss the critiques that Europe needs to take any action to reform GDPR or in reaction to Schrems II.

Key European industry bodies and firms are also providing the much-needed local support for a new agreement, which counter the misconception that data flows are only relevant to U.S. firms. A coalition of German trade associations (including the Federation of German Industries (BDI)) called for increased efforts by both the German government and the European Commission to quickly bring about legal certainty for companies as well as a long-term political solution. Likewise, Digital Europe has made ongoing calls for a new agreement.

U.S. officials should continue good faith efforts to negotiate a replacement, but given the countervailing trends toward digital protectionism in Europe over the last year (and before), they should also put forth a deadline for an agreement and start preparing retaliatory measures in the event that Europe makes it impossible to reach a reasonable and pragmatic agreement.