Marshaling National Power Industries to Preserve America’s Strength and Thwart China’s Bid for Global Dominance

China is on the march to dominate advanced industries that underpin national power in the 21st century. To protect U.S. economic strength and national security, policymakers must jettison old techno-economic and trade policy doctrines and adopt a new national power industry strategy.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Key Takeaways

Contents

Today’s Historical Turning Point 17

The Nature and Importance of National Power Industries 48

America’s Power Industry China Strategy Choices 64

Consumer Welfare and Progressive Economics Vs. National Power Economics 91

An Operational Strategy For “Stand and Fight” 98

A National Power Industry Strategy Framework. 115

The Political Economy of National Power Industry Strategy 117

Appendix 1: Selected Chinese Advanced Industry Policies 130

Appendix 2: Key Takeaways for Major U.S. Policy Areas 133

Appendix 3: National Power Industry Typology and Categorizations 136

Forward

The United States risks losing its technological leadership to China at the expense of its economic and national security.[1] That is why the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) established the Hamilton Center on Industrial Strategy.[2] It is dedicated to advancing a comprehensive framework and specific policy agenda to maintain America’s competitive edge.[3]

With America now facing an aggressive and often malign challenge from China, there is an urgent need for stronger policy advocacy and thought leadership that articulates the case for robust national strategic-industry policy.[4] This policy must focus on critical, dual-use technologies and industries in advanced, traded sectors of the economy. Such an approach requires firmly rebutting the deeply held view of most economists and many policymakers that all industries are created equal. In other words, no more “potato chips, computer chips—what’s the difference?” Strategic-industry policy demands making tough political choices and “picking winners”—not individual firms or specific technologies, but rather certain industries and categories of technology that are critical to the nation’s future. Finally, it requires a government that is knowledgeable and sophisticated about industry operations and the effects of policy on traded sectors.[5]

Under the Hamilton Center, ITIF has launched a major research project focusing on China’s industrial goals and strategies, their impact on U.S. industrial power, how U.S. policymakers and experts should think about this challenge, and what a detailed and comprehensive policy agenda should look like. The project’s core thesis is that a specific set of industries acts as a vital wellspring of national power, either because they directly support the defense industrial base or because they limit dependence on U.S. adversaries that could be used for coercion. ITIF calls them “national power industries.”

Without major structural change in U.S. policy—akin to the strategy America implemented at the beginning of the Cold War—we believe that the United States’ national power industries will weaken significantly, if not die, in turn weakening the U.S. defense industrial base and giving China techno-economic leverage over America in a broad range of areas, not just rare earth minerals. At its core, this challenge requires formulating and implementing a national power industry strategy grounded not just in economics but also in corporate strategy literature.

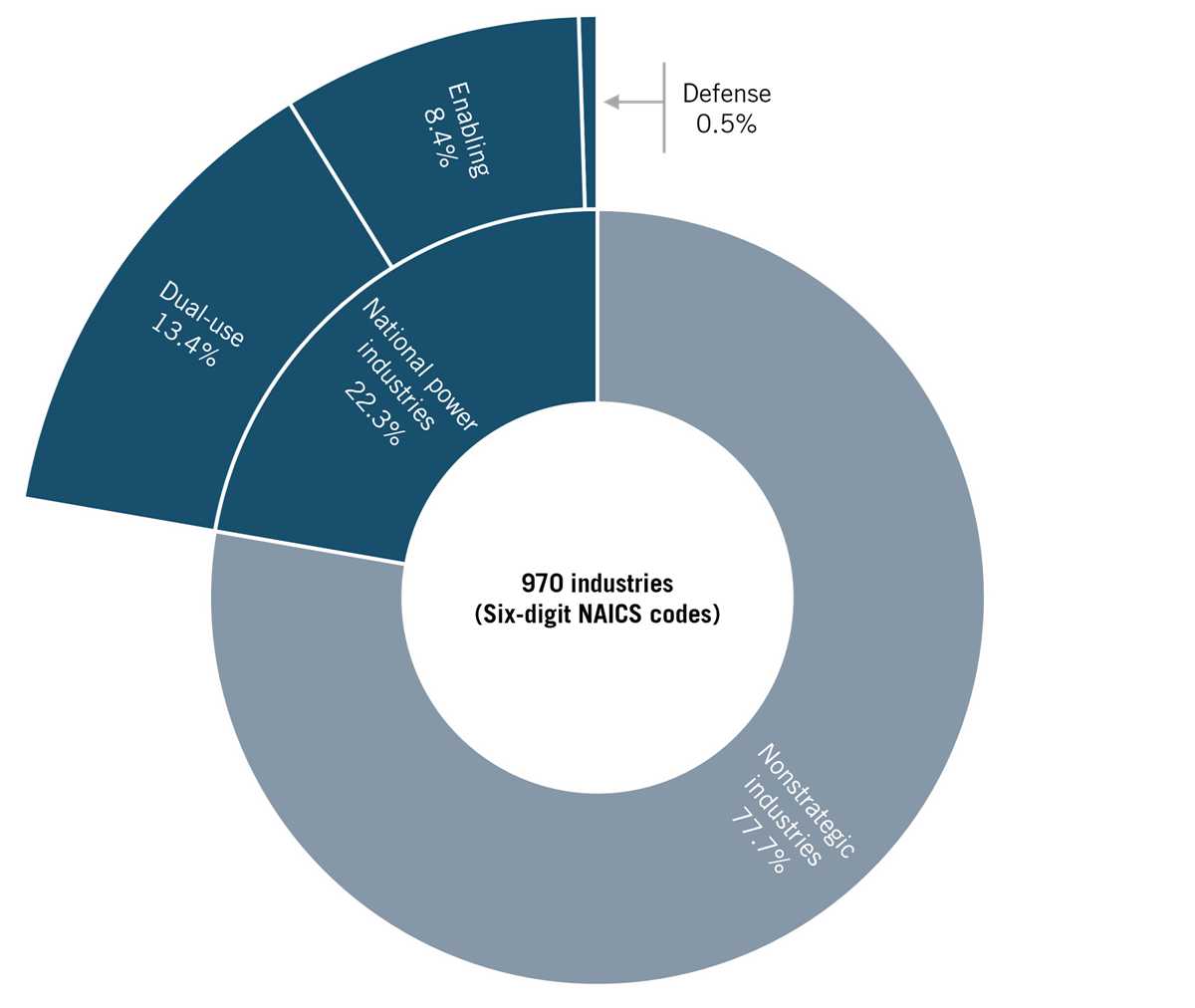

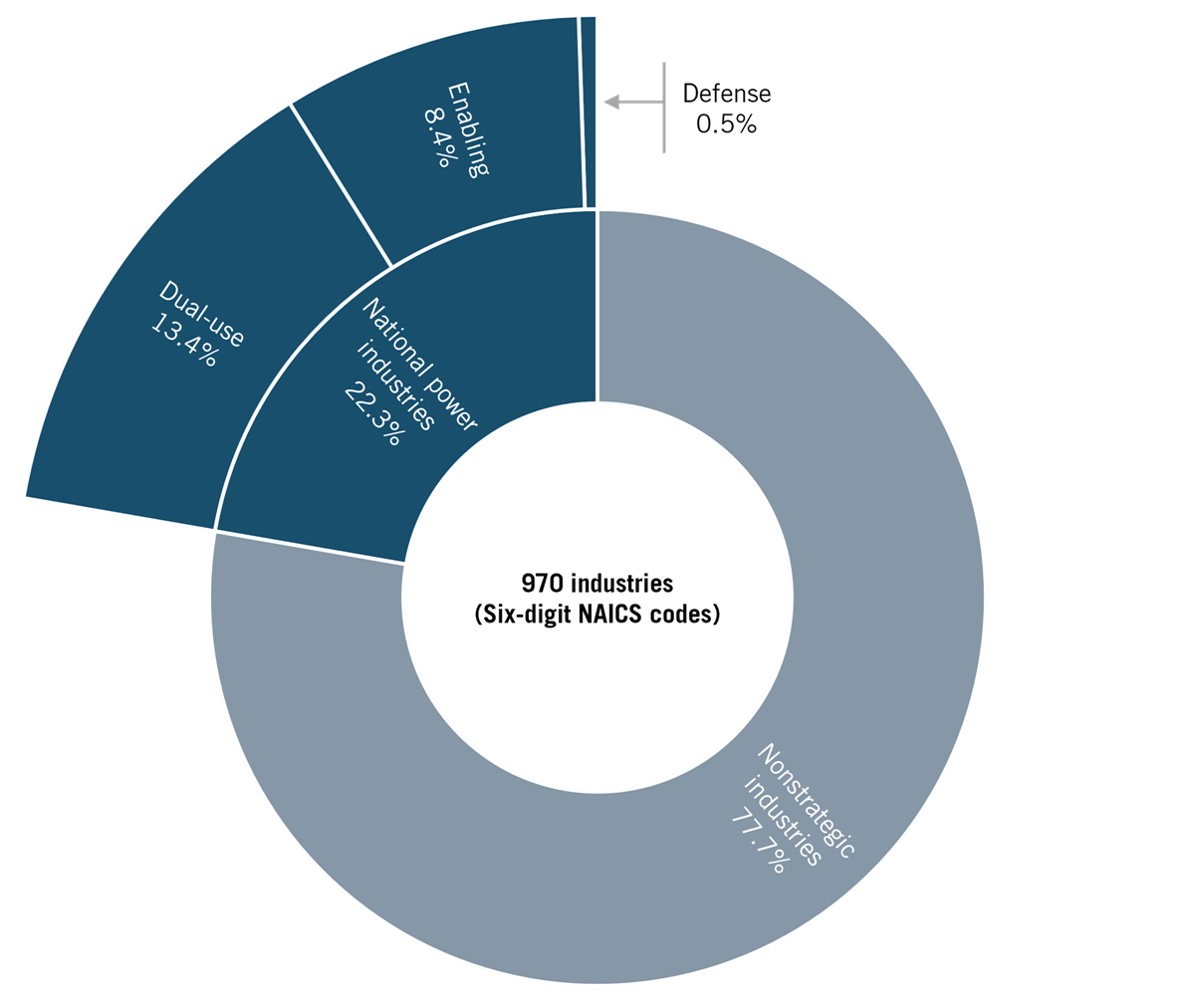

This project focuses on several objectives. First, this report provides an overarching analytical framework and an enumeration of the stakes, including an assessment of the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP’s) intent. It then proposes the concept of national power industries, classifying U.S. industries into four categories of relative importance to the power industry competition. The report examines why current techno-economic and trade policy doctrines that dominate Washington, DC, are flawed and misguided, then summarizes 18 different strategic directions offered by conventional foreign policy thinking and explains why these approaches are inadequate. Following this analysis, the report draws on corporate strategy literature to outline what a coherent and effective grand strategy for the national power industry competition should look like. Finally, it examines the political economy of implementing such a strategy.

After this report, the project will conduct a series of quantitative and qualitative analyses examining the past and present performance of U.S. power industries, including comparisons to China. This analysis will examine impacts on the overall U.S. economy, the 50 states, and the competition between China and the United States for global market share in national power industries.

Finally, the project will outline a comprehensive agenda for U.S. industrial policy that can be implemented by Congress and the administration. This will include both specific policies and recommendations for reorganizing government.

Executive Summary

The Strategic Imperative

The United States faces an existential challenge in China’s systematic campaign to dominate the advanced industries that enable national power in the 21st century. Unlike any competitor in American history, China combines the continental scale of a 1.4-billion-person economy with a Marxist-Leninist political system explicitly committed to achieving techno-economic supremacy over the Western democratic world. This is not normal economic competition between market economies—it is a carefully orchestrated, multi-decade strategic campaign to displace U.S. industrial capabilities, weaken allied nations, and fundamentally reshape the global order under CCP leadership.

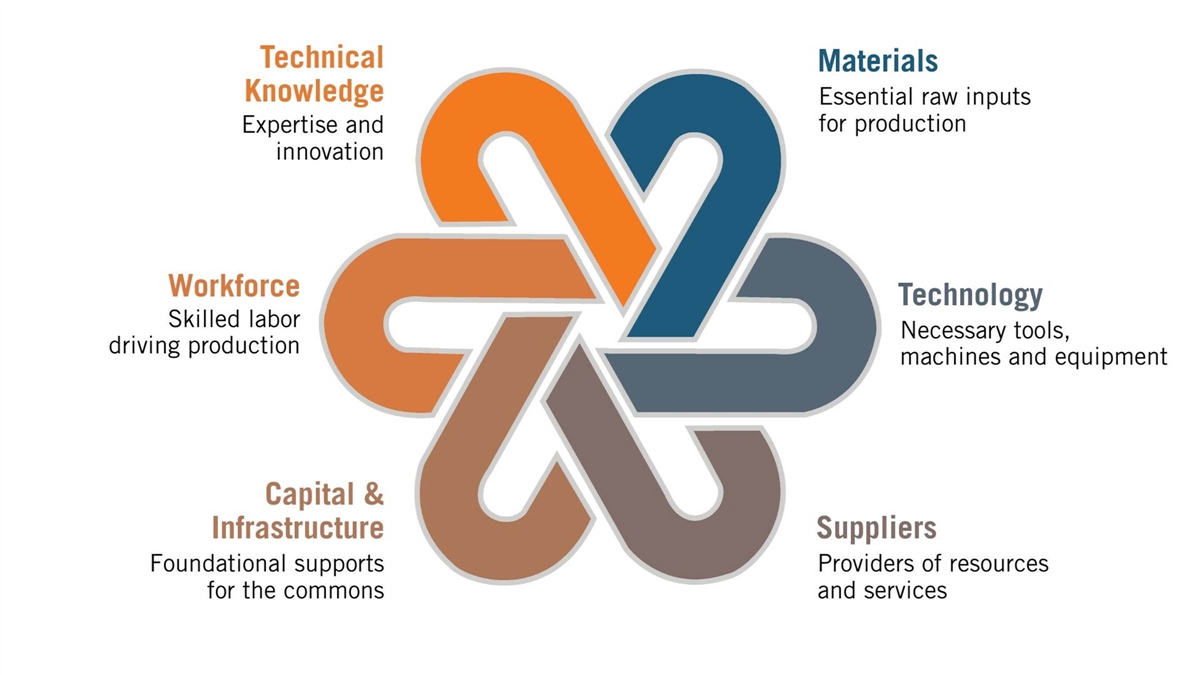

The stakes transcend economics. National power today depends on strength in what this report terms “national power industries”—a spectrum of sectors spanning pure defense production, dual-use technologies employed in both military and commercial applications, and enabling industries that support the broader industrial commons. These include semiconductors, aerospace, biopharmaceuticals, telecommunications equipment, advanced chemicals, precision machinery, robotics, artificial intelligence (AI) systems, and dozens of other sectors in which weakened or fatally injured firms would grant China dangerous leverage over the United States and its allies, as well as weaken U.S. defense production capabilities.

On its current trajectory, it is likely that China will soon amass significantly greater capabilities than the United States will in national power industries.

This competition occurs against a backdrop of American policy failure. For over two decades, U.S. leaders across both parties have operated under the assumption that China was becoming a “normal” market economy that would gradually liberalize politically and economically. That assumption has proven catastrophically wrong. China today is more authoritarian, more aggressive internationally, and more committed to state-directed capitalism than at any point since Mao’s death.

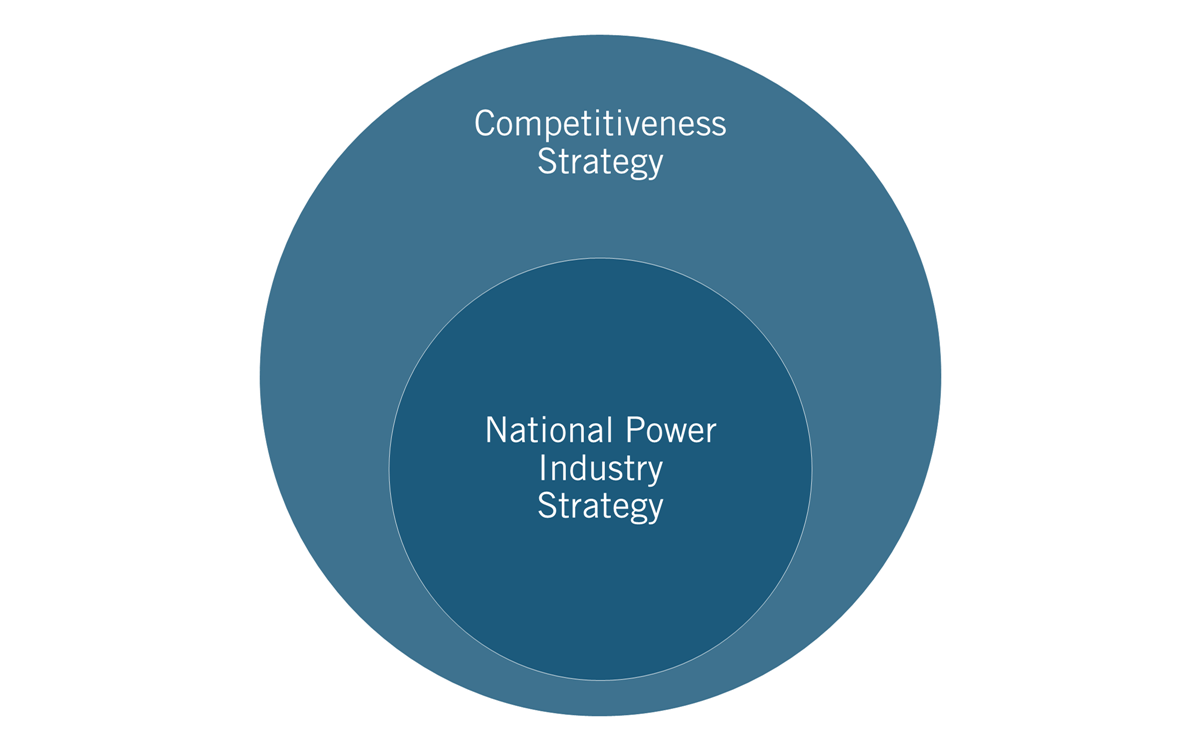

On its current trajectory, it is likely that China will soon amass significantly greater capabilities than the United States will in national power industries. With those greater capabilities will come geostrategic hegemony over the West, unless the United States forestalls that outcome by adopting a new, transformative national power industry strategy that goes beyond a mere competitiveness or national innovation strategy. This is not a war that the United States and allies can win in the sense of significantly weakening or retarding the growth of China’s own national power industries. The only way Chinese attacks will end is if China becomes a free, democratic country. But the United States and allies can avoid defeat—keeping their national power industries relatively strong—by working together and adopting national power industry strategies.

Understanding the Chinese Communist Party’s True Objectives

Perhaps the most damning evidence of Chinese intentions comes from internal Communist Party documents and speeches intended for party members rather than foreign audiences. As China scholar Daniel Tobin has documented, these reveal a regime explicitly committed to Marxist-Leninist global ambitions that go far beyond merely moving up the value chain and growing its economy.

Xi Jinping has repeatedly framed China’s rise in ideological terms, stating that “scientific socialism is full of vitality in 21st century China” and that China offers “a new option for other countries and nations who want to speed up their development while preserving their independence.” In a 2013 speech to senior party officials, Xi declared that “the viewpoint of historical materialism that capitalism is doomed to failure and socialism will prevail” remains valid, and that China must “seize the initiative, win the competitive edge, and secure our future” in a “long-term cooperation and rivalry between the two social systems.”

Documents from the party’s 20th Congress state that China’s success has “significantly shifted the worldwide historical evolution of the contest between the two different ideologies and social systems of socialism and capitalism in a way that favors socialism.” Chinese leaders explicitly describe their work as part of a “great struggle” and “systems contest with Western capitalist democracy,” using terminology that leaves no ambiguity about their intentions.

On technology and industry specifically, party documents are equally explicit. The minister of Science and Technology wrote in the People’s Daily that “the scientific and technological revolution and the contest between major powers are intertwined; the high-tech field has become the forefront and main battlefield of international competition.” Another official commentary stated: “To a certain extent, those who gain access to the Internet will gain the world. Core technology is an important weapon for the country.”

China’s Made in China 2025 plan, while officially downplayed after international backlash, clearly articulates the goal: “Building an internationally competitive manufacturing industry is the only way China can enhance its comprehensive national strength, ensure national security, and build itself into a world power.” The plan calls for China to “seize the commanding heights of a new round of competition in the manufacturing industry” and achieve innovation leadership “ranking first globally.”

The CCP follows a predictable playbook across industry after industry.

Leading Chinese scholar Lu Yongxiang stated in 2024 that “by 2035, ‘Made in China’ will surpass the United States and become the global leader,” noting this would thrust the world into a “new era”—explicitly referencing an era of Chinese dominance. These are not the words of a nation seeking merely to “catch up” or achieve “legitimate development.” They are the explicit articulation of a campaign for global advanced industrial hegemony.

China’s actions match its rhetoric. The CCP follows a predictable playbook across industry after industry. First, attract foreign investment by promising market access. Second, coerce technology transfer through joint venture requirements and other mechanisms—pressure the U.S. Trade Representative has characterized as “particularly intense.” Third, support domestic firms in copying and incorporating foreign technology while building indigenous capabilities through programs such as the 2006 Medium- and Long-term Program for Science and Technology Development, which identified 402 core technologies to master.

Fourth, carve out and protect the Chinese market for Chinese firms, excluding foreign competitors once domestic champions can reasonably serve the entire Chinese market. Fifth, provide massive subsidies—estimated at minimum 1.73 percent of Chinese gross domestic product (GDP) annually, or over $400 billion per year, though actual figures are likely far higher accounting for provincial and local support. Finally, support Chinese firms “going out” to capture global market share, particularly in developing nations through Belt and Road Initiative investments exceeding $1 trillion. These dwarf the minimal industrial subsidies the U.S. government (USG) provides.

The scale of Chinese subsidies dwarfs anything in Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) nations. A German institute found that in 2022, 99 percent of listed Chinese firms received direct government subsidies, with electric vehicle (EV) maker BYD alone receiving over $3.7 billion. Chinese industrial subsidies were 4.5 times greater than U.S. subsidies as a share of GDP. Combined with a chronically undervalued currency, suppressed domestic consumption, and closed markets, these subsidies have enabled Chinese firms to sell below cost for years or decades, systematically destroying foreign competitors’ market positions.

This is not to say that all Chinese efforts or innovation are win-lose. If China invents a cure for Alzheimer’s, the world benefits (assuming the United States or its allies would not also do so). But this would also reduce U.S. (and allied) strength in the pharmaceutical industry.

Three Flawed Strategic Responses

Overall, the policy debate about China is largely dominated by international relations scholars and experts, not business or industrial strategy experts. The former are aware of the global competition for leadership in advanced industries, but they largely see it as subservient to overall foreign policy considerations and goals. Moreover, few understand the operation of advanced industries, the nature of the competition, or the importance of barriers to entry and reentry. As such, the prevailing narratives largely ignore techno-economic and trade war implications and the implications for U.S. power.

Current U.S. thinking about China coalesces around three main strategic approaches, all of which are inadequate to the challenge.

The Engagers: Cooperation Above All

The first camp, still influential in much of the U.S. foreign policy establishment, prioritizes maintaining cooperative relations with China, even in the face of CCP behavior that harms U.S. national power industry capabilities. These experts argue that China’s growth benefits global prosperity, that Chinese cooperation is essential for addressing climate change and other global challenges, and that confrontation risks becoming a catastrophic conflict.

A 2019 open letter signed by over 100 prominent scholars claimed that “we do not believe Beijing is an economic enemy or an existential national security threat” and argued that “the fear that Beijing will replace the United States as the global leader is exaggerated.”

This camp consistently minimizes Chinese malfeasance while emphasizing supposed benefits of engagement. They cite Chinese economic growth as driving global prosperity (ignoring that China’s persistent trade surpluses actually reduce GDP elsewhere). In arguing that cooperation is needed on issues such as climate change, pandemic response, and AI governance, they gloss over the question of why the United States should be the supplicant when China has equal or greater interest in addressing these challenges.

Their fundamental error is treating China as a partner rather than a strategic competitor. Engagers assume that continued dialogue and economic ties will moderate China’s behavior, when two decades of evidence proves otherwise. They prioritize the process of engagement over the substance of outcomes, accepting Chinese predatory practices as the price of maintaining access and conversation.

The Deniers: Wait for China’s Collapse or Assume Inherent U.S. Superiority

A second camp acknowledges China’s rise but counsels patience, predicting that internal contradictions will lead to Chinese economic stagnation or political crisis. These analysts point to demographic decline, the housing bubble, government debt, and the inefficiencies of state capitalism as harbingers of inevitable Chinese failure. To be sure, many advance the well-trodden prescriptions such as improved K-12 education, more high-skill immigration, smarter regulation, and more government spending on science. But they will not go so far as to support a national power industry strategy.

This “Peak China” thesis is seductive because it requires no painful U.S. policy changes. If China is destined to collapse under its own weight, the United States need only wait and maintain its existing approaches to the economy, trade, and national security. Proponents cite any negative Chinese economic news as evidence that their predictions are materializing, while ignoring continued Chinese gains in technological capabilities and global market share of advanced industries.

The fatal flaw is mistaking China for the Soviet Union. Unlike Soviet command economics, Chinese state capitalism has proven remarkably effective at generating growth and technological advancement. The CCP studied why the Soviet Union failed and adopted fundamentally different economic management—allowing market forces to operate within state-directed strategic frameworks rather than attempting to centrally plan everything.

Moreover, even if China faces economic headwinds from demographics or debt, these business-cycle challenges do not negate its structural advantages in the techno-economic competition. Chinese firms will continue benefiting from massive subsidies, protected markets, and patient capital regardless of GDP growth rates. Waiting for China to self-destruct while Chinese companies dismantle Western industries one after another is a prescription for defeat.

The Innovationists: Technology Will Save Us

The third camp acknowledges the challenge China presents but argues that American innovation superiority will enable the United States to prevail. These “dynamists” focus on deregulation, immigration reform, scientific research funding, and nurturing entrepreneurship—particularly in cutting-edge fields such as AI, quantum computing, and synthetic biology.

This view holds that the United States need not defend legacy industries because American innovators will create entirely new sectors and the United States will lead them. Why fight over solar panels or EVs when we can dominate AI and quantum? The prescription is to boost science funding, reduce regulatory barriers, import more STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) talent, and trust that Silicon Valley-style innovation will deliver victory.

The problems with this strategy are multiple. First, with a few exceptions (e.g., AI), it is industry-agnostic—there is no guarantee that market-driven innovation will produce capabilities in sectors that matter most for national power. Second, the United States has repeatedly lost production of technologies it invented, from televisions to solar panels to batteries, as other nations have commercialized American discoveries. Innovation alone does not ensure domestic production or competitive strength.

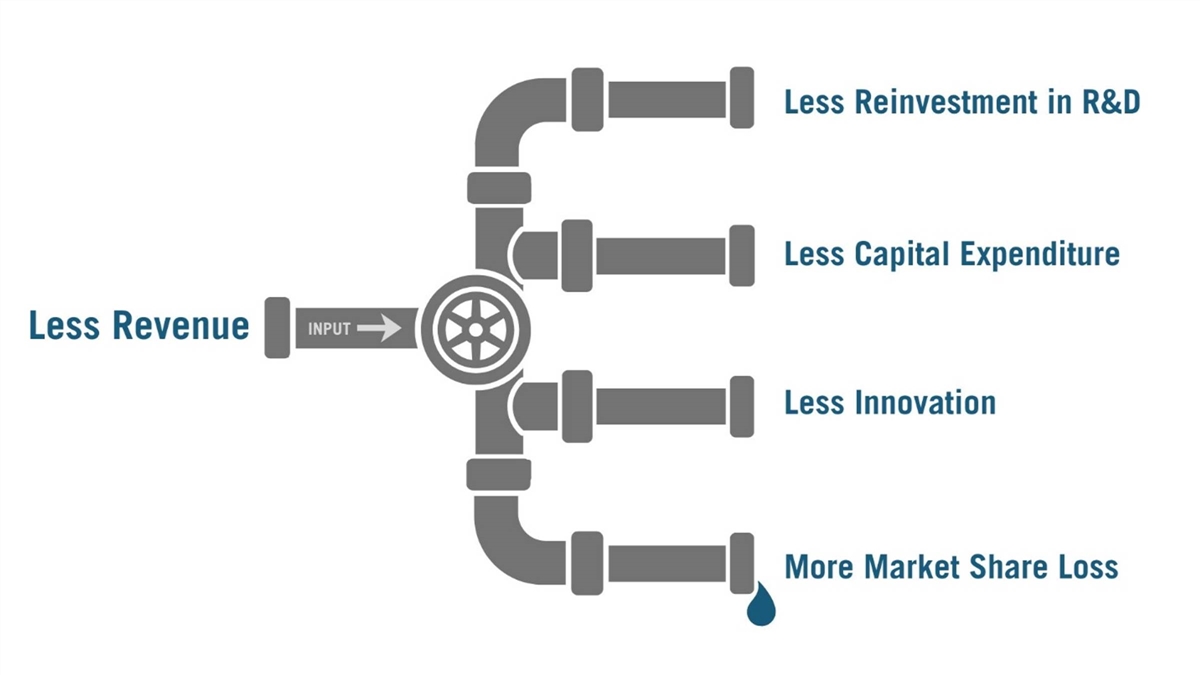

Third, advanced defense systems increasingly rely on commercial technologies (spin-on rather than spin-off), making a strategy that abandons commercial sectors to China while hoping to maintain defense-only production unrealistic and prohibitively expensive. Fourth, the “industrial commons”—the ecosystem of suppliers, skilled workers, and manufacturing capabilities—erodes when industries disappear, making future innovation harder. Intel founder Andy Grove’s warning resonates: “Abandoning today’s ‘commodity’ manufacturing can lock you out of tomorrow’s emerging industry.”

Finally, China is not ceding emerging technologies. Chinese firms are competitive or leading in AI (see Alibaba, Baidu, and DeepSeek), quantum communications, commercial space, robotics, and biotechnology. The notion that the United States can retreat to “higher ground” in emerging tech while China dominates established industries ignores that Chinese firms are aggressively pursuing both.

Why Current U.S. Economic Policy Frameworks Fail

The deeper problem is that dominant U.S. economic doctrines are fundamentally mismatched to the era of national power industry competition.

Consumer Welfare Economics

The reigning paradigm in U.S. economic policymaking—which critics call “neoliberalism”—treats all industries as equivalent. Financial services and semiconductor fabrication are no different; both simply respond to market signals. The goal is to maximize consumer welfare through efficient resource allocation, which markets achieve better than governments do.

The reigning paradigm in U.S. economic policymaking—which critics call “neoliberalism”—treats all industries as equivalent.

In this framework, Chinese subsidies (including low labor costs and lax environmental regulations) are gifts to American consumers (lower prices!), not strategic attacks. Trade deficits reflect American prosperity (we’re rich enough to buy foreign goods!), not industrial weakness. Offshoring production to China demonstrates smart capital allocation by U.S. firms seeking higher returns, not a national security vulnerability.

Consumer welfare economics has no concept of strategic industries or national power. Its proponents argue that “countries don’t compete, only companies do” and that concerns about industrial structure reflect economically illiterate protectionism. The Peterson Institute epitomizes this view, arguing that U.S.-China trade is “clearly win-win” and that “Chinese companies have a right to compete with U.S. companies and succeed in any sector, including in high-tech.”

This doctrine might have been adequate when America faced no serious techno-economic competitor; it is catastrophically inadequate against China’s state capitalist predation. Markets have no inherent reason to preserve semiconductor fabrication, aerospace, or pharmaceutical production domestically. They are equally happy producing legal services, retail, and hospitality, none of which enable national power.

But the reality of this techno-economic and trade attack fundamentally undercuts the foundation of consumer welfare economics and exposes its inability to address the current challenge. If national power is the ultimate goal, not consumer welfare, then this doctrine fails, at least in guiding the share of the economy composed of national economic power industries. If a nation’s industrial mix is critical, then a doctrine that gives equal weight to potato chips and computer chips fails.

Neo–New Deal Progressivism

The ascendant alternative on the Left is equally unsuited to the challenge. Neo–New Dealism focuses on redistribution, social justice, and worker welfare overgrowth and competitiveness. Its industrial policy priorities are human services (childcare, eldercare), climate-focused sectors (renewable energy), and breaking up large corporations through aggressive antitrust.

While rhetorically supporting “industrial policy,” progressives’ actual agenda—drug price controls, restricting intellectual property (IP), mandating labor standards that limit automation, attacking profitable corporations as exploitative—systematically weakens the large advanced-technology firms that must serve as national champions against Chinese competitors.

Moreover, neo–New Dealism’s massive social spending agenda would consume the fiscal resources needed for strategic industrial investment. Its anticorporate ideology and deep suspicion of business-government collaboration make the public-private partnerships required for an effective national power industry strategy politically toxic.

The reality of the CCP’s techno-economic and trade war on the West undercuts the foundations of neo–New Deal progressivism. If the United States is in an existential contest for global power, then boosting taxes and regulations on business is especially ill-advised, as are the neo-Brandeisian campaign to destroy large corporations and separate unrestrained demands from organized labor. Progressive advocates know this quite well, which is why they go to any end to deny that China is even a competitor.

What’s Required: National Power Industry Strategy

The United States needs a fundamentally new framework: a national power industry strategy. This approach recognizes the following:

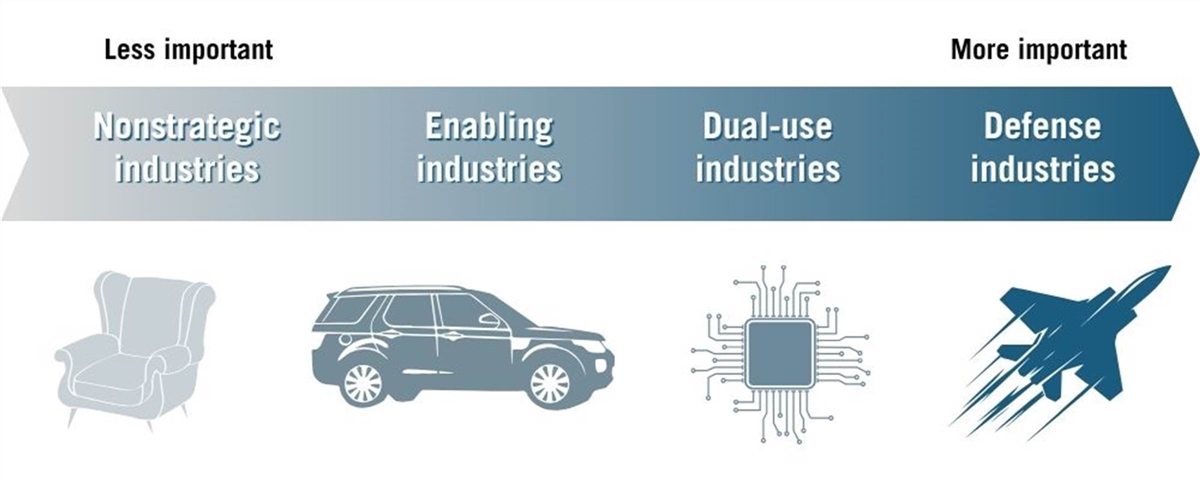

▪ Industries differ fundamentally in strategic importance. Semiconductors and furniture are not equivalent. Some sectors—defense, dual-use, and enabling—are critical to national power and must be prioritized even at short-term economic cost.

▪ Markets are indifferent to national power. Unregulated market forces will not automatically preserve strategic capabilities. Government must actively shape industrial structure through strategy, not just generic competitiveness or innovation policies.

▪ China is a strategic competitor, not a normal trading partner. Chinese mercantilism requires defensive measures (restricting imports produced unfairly) and offensive support (strengthening domestic champions in national power industries) that violate free-market and progressive orthodoxies.

▪ Production matters as much as innovation. The United States cannot rely on inventing technologies that China then produces. Manufacturing capabilities, supply chain resilience, and industrial commons must be preserved domestically in strategic sectors.

▪ Long-term strategic positioning trumps short-term efficiency. Maintaining redundant capacity, subsidizing strategic industries, and accepting higher consumer prices are necessary costs of not losing the techno-economic war.

This requires jettisoning the deeply held view that governments should not “pick winners.” Markets might optimize GDP growth, but only by happenstance will this generate needed national power industry capabilities. Policymakers must embrace strategic industry selection and support, drawing on business strategy frameworks rather than consumer welfare economics.

Implementation Barriers

The political economy obstacles to a national power industry strategy are severe. U.S. business leaders, shaped by decades of financial capitalism prioritizing quarterly returns and shareholder value, distrust government involvement and focus myopically on firm-level profitability rather than systemic strength. Unlike their predecessors from the 1940s–1970s who saw themselves as corporate statesmen with responsibilities to the broader capitalist system, today’s executives view government industrial policy as either incompetent interference or the thin edge of socialist control.

Labor unions pursue short-term wage gains that often undermine firms’ long-term global competitiveness because they are unable to escape the prisoner’s dilemma of aggressive bargaining today leading to job losses to less-constrained Chinese rivals tomorrow.

Conservative organizations reflexively oppose the government activism required for industrial strategy, while progressive organizations reflexively oppose supporting corporations. Neither party’s dominant coalition supports the combination of strong state capacity and empowered corporate champions that a national power industry strategy requires.

Perhaps most critically, the USG itself lacks the analytical capacity, institutional structures, and personnel with expertise to formulate and execute sophisticated industrial strategy. Unlike China, where officials study industrial policy as a discipline and spend careers mastering sectoral dynamics, U.S. policymakers typically have backgrounds in law or generalist economics divorced from operational understanding of specific industries and technologies.

The Path Forward

The United States requires political, policy, and institutional transformation comparable to previous pivots after the War of 1812, the Civil War, and World War II. In all three cases, war provided the spur to overcome inertia and interest group resistance. We certainly hope it will not take a physical war to achieve similar transformation today. Either way, the organizing principle of economic policy must shift from maximizing consumer welfare or spurring social justice to ensuring that the United States maintains superior capabilities in national power industries relative to China. The simplest measures of this are the share of these industries’ global output that is produced in the United States and the share of U.S. production that occurs in allied nations. Related measures are the technological sophistication of U.S. products and services in national power industries compared with those of Chinese competitors.

This demands classifying industries by strategic importance, developing sophisticated strategies for priority sectors informed by business strategy principles rather than economics, restricting unfairly traded Chinese goods’ access to allied markets, substantially increasing public and private investment in strategic sectors (on the order of $100 billion per year in tax incentives and direct expenditures for at least a decade), coordinating with allies to present unified responses, and building government institutional capacity for industrial strategy.

The United States requires political, policy, and institutional transformation comparable to previous pivots after the War of 1812, the Civil War, and World War II.

The costs will be significant: Implementing a national power industry strategy will bring higher prices for certain consumer goods, increased government spending, greater fiscal discipline elsewhere, and reduced returns for some investors as capital is channeled toward strategic rather than merely profitable uses. But the alternative is worse: a future in which Chinese dominance of advanced industries leaves the United States dependent on an adversary for critical technologies, unable to defend its interests or protect its allies, and relegated to second-tier status in a China-dominated world order.

Conclusion

History shows that America can make fundamental pivots when circumstances demand. Whether it can do so absent the shock of military conflict—which might come too late, after critical capabilities are already lost—remains the defining question of our era. The window for effective action is narrowing. Chinese positions in industry after industry are becoming entrenched, protected by economies of scale, learning curves, network effects, and the enormous barriers to reentry that characterize advanced manufacturing. The reality is that once advanced industry capabilities are lost, they are extremely difficult to resurrect.

The choice facing America is stark and unavoidable: Fundamentally reform techno-economic policy now by embracing the uncomfortable truth that some industries matter far more than others—and by recognizing that preserving them requires active government strategy—or accept a managed decline into second-tier status while China’s techno-economic dominance translates into geopolitical supremacy. There is no third option, no magical innovation breakthrough that will solve the problem without hard choices and real sacrifices.

The United States remains far stronger than any declining power in history. Its advantages in innovation ecosystems, allied networks, capital markets, universities, and democratic legitimacy provide a foundation for successful competition if properly mobilized. But time is not on America’s side. Every industry lost makes recovery harder; every year of Chinese industrial expansion shifts the balance further; every failure to act because it violates free-market or progressive orthodoxies surrenders ground that cannot be regained. The techno-economic war with China is the central challenge of the 21st century. America’s response will determine not just its own future but the future of the liberal democratic world.

Introduction

National power is a country’s ability to both prevent other states from taking actions against its core interests and impose its will on other nations. Traditionally, national power was largely determined by military power. In the globally integrated economy of the 21st century, a key enabler of national power is strength in industries that not only support weapons system development and production, but also provide leverage over adversaries and limit their leverage over us. This leverage can be directly related to defense, as when China produces key materials and parts going into U.S. weapons systems (which it currently does) or indirectly such as when China is able to cripple key U.S. industries.[6] We call these key industries that are vital to the country’s strategic interests “national power industries.”

With this context, let’s start with a series of key questions that, if answered in the affirmative, should form an immutable logic chain in support of a paradigmatically different kind of U.S. techno-economic and trade policy.

First, does the United States need to be the strongest power nation on Earth, especially over China? If it doesn’t, then status quo economic and trade policies from the Left and Right will suffice.

Second, if it does, then to what extent does national power come from relative strength in certain industries, particularly military, dual-use, and industries that enable the industrial commons that defense and dual-use industries rely on? If power is only loosely related to those types of industries, then the status quo policies will suffice.

Third, if national power is significantly enabled by a certain class of industries, then to what extent is China seeking and capable of gaining relative strength over the United States and its allies in these industries? Related to that, is competition in these industries mostly win-lose, wherein China’s gains come at the expense of U.S. (and allied) losses? If the answer is either that China is not succeeding in these industries or that its success does not come at the expense of U.S. capabilities, then status quo policies will suffice.

But if the answer to all these questions is yes—as ITIF argues for in this report—then the implications are profound. The logic chain points inexorably to the conclusion that unless the United States (and its allies) is stronger than China in particular industries and thus has more techno-economic leverage over China than China has over us, then U.S. power vis-à-vis China will be limited and there will be transformative consequences for the global balance of power and U.S. national interests.

That logic chain has, or at least should have, profound implications for U.S. techno-economic and trade policy. It establishes that the conventional neoclassical, consumer-welfare–based economics that has dominated U.S. policymaking for more than 50 years needs to be scrapped for the simple reason that it is agnostic to national industry structure. As such, unless the country adopts a new strategy, not losing the power industry war with China will come down to happenstance and luck. This is because the dominant view in Washington, even among most Democrats, is that markets determine industry structure and all industries are of equal value. Financial services are no different than semiconductor production. It cannot be stressed enough that the acceptance of this core doctrine underpins virtually all U.S. techno-economic and trade policy. It explains the support for free markets and free trade and the aversion to “picking winners.” It explains why economic policy on the Right is about enabling market forces and on the Left about achieving better social policy outcomes by taxing and regulating the private sector. Both are indifferent to industry structure.

In the past, this industry-agnostic, market-economics framework was not detrimental to national power because the United States did not face a competent techno-economic adversary in the form of the Soviet Union. In fact, the Soviet economy was incredibly fragile, and it made the U.S. economy seem like a goliath by comparison.[7] That unfortunately instilled a dangerous hubris into policy thinking that America suffers from to this day. Now that America faces a likely superior techno-economic adversary in the form of China led by the CCP, that doctrine and the policies that flow from it are no longer purpose-fit and need to be retired as quickly as possible.

A world in which the United States (and allies) cannot lose power industry strength is a world that calls for a fundamentally new kind of techno-economic and trade policy.

But the next question is whether the usual alternatives to free-market economics—competitiveness policy, innovation policy, technology policies, and/or manufacturing policy—are the right paths to follow. To be sure, these differ from free-market frameworks in that they privilege certain things over others: a better trade balance in advanced industries, more innovation, more output, and jobs in technology industries and manufacturing. However, while certainly a better fit for the world the United States and allied nations now find themselves in, these approaches are still inadequate because they advocate only for broad outcomes, and like free-market doctrine, they are indifferent to power industry strategy. Even if these policies are adequate and successful—to date, they have been inadequate—there is no guarantee that adopting them would produce requisite capabilities in the industries that the United States most needs to bolster in order to have superior power over China. If we get more toy and lumber manufacturing, but not more machine-tool and semiconductor manufacturing, the United States will lose out to China.

In short, the United States (and its allies) need to be stronger than China in the industries that are wellsprings of national power in order to prevent China from asserting power and leverage over the United States and its allies. And a world in which the United States and its allies cannot lose strength in national power industries is a world that calls for a fundamentally new kind of techno-economic and trade policy.

Circumstances have compelled the United States to make significant structural techno-economic and trade policy changes before: after the War of 1812, after the Civil War, and after WWII. It is once again time for America to make such fundamental changes in policy. The stakes then were less significant for the simple reason that there was much less global integration, and our adversaries were weaker. Today, the stakes and the conditions are fundamentally different. China is the first nation in over 125 years with the ability to challenge the United States from a techno-industrial perspective.

In previous instances, it took wars to trigger this kind of fundamental structural change in policy and institutions. Hopefully, it will not take a kinetic war to bring needed change today. Because if it did, there is every reason to believe that the United States and allies will already have irrevocably lost many of their power industry capabilities and prohibitive barriers to entry will leave slim prospects for regaining them.

Unfortunately, status quo thinking and vested interests hinder power-industry economics from emerging. First, most foreign policy experts, even while acknowledging the authoritarian rule of Xi Jinping, continue to believe that China is a normal, market-oriented, emerging economy and that “socialism with Chinese characteristics” is just a slogan used for domestic purposes to mask China’s true capitalist nature. Second, while there is growing awareness of the West’s techno-economic dependence on China, that dependence is generally seen as limited to a few narrow areas, such as rare earth minerals, which are said to be easily fixed with the right policies. Third, the conventional view of international economics is both that trade is welfare-maximizing for all parties and that while companies may compete, countries do not. In other words, there is no battle for global market share in key national power industries. Finally, even the most die-hard China hawks and manufacturing supporters do not view the world in terms of power-industry competition with China. For them, getting more U.S. manufacturing jobs is the goal, whether they support national power or not.

In a world with these assumptions, status-quo responses suffice. The United States and its allies compete with China and others for market share in advanced industries, and we win some and lose some. And to the extent we lose, we just create new industries and firms because of our inherent innovation strengths. Besides, old industries are for losers. To the extent trade barriers arise, they are handled through normal bilateral or multilateral processes. And domestically, the United States can rely on existing economic policies and institutional structures to ensure reasonable levels of competitiveness and prosperity.

U.S. techno-economic and trade policy needs to have as its inspiration and fundamental organizing principle not ensuring economic freedom and efficiency, not social justice, and not stopping climate change—but also not losing in a wide array of strategic industries.

Too many U.S. experts, pundits, and policymakers see the CCP as perhaps a bit more focused on industrial policy and a bit less interested in obeying global trade rules than the West is, but not an assertive Marxist-Leninist actor that stands apart. As such, there is no need for a radical overhaul of U.S. techno-economic and trade policy. (Obviously the Trump administration and most China hawks are not in this camp.) As described herein, there are many reasons for the resistance to accept this new reality. But this new reality needs to be accepted and acted upon.

This report proceeds from the fundamental view that the CCP seeks global hegemony, that it views techno-economic dominance in national power industries as a key pillar of that long-standing campaign, and that it will do virtually anything to win that quest. As such, the United States and its democratic allies who stand for freedom and human rights need to respond by fundamentally rethinking and restructuring their techno-economic and trade policies.

This boils down to a simple but fundamentally far-reaching proposal: U.S. (and allied) techno-economic and trade policy needs to have as its inspiration and fundamental organizing principle, not ensuring economic freedom and efficiency, not prioritizing social justice, not stopping climate change, and not keep AI from taking over—but instead not losing in a wide array of strategic industries. I say “not losing,” as opposed to winning, because China is such a formidable competitor—with a massive domestic and friendly international market (e.g., Belt and Road nations) and an enormous “bank account” to subsidize its way to power industry market share—that it is likely not be possible to keep Chinese firms from being the leaders in many national power industries, especially in non-OECD markets. But what the West can and must do is to avoid losing its own power industry capabilities.[8]

National power industries are not just any manufacturing or even technologically advanced industries. They can be thought of as three categories, from most important to least: military industries, dual-use industries, and enabling industries. Examples of military industries are guided missiles and tank production. Examples of dual use are electronic displays and semiconductors, which are used in both defense and commercial industries. Imagine as a thought exercise that China dominated optics and displays. This would give China the ability to cripple U.S. defense capabilities because optics and display technologies are critical for night-vision goggles, heads-up instrument displays for fighter pilots, rifle scopes, and myriad other military applications. Enabling industries include automobiles and heavy construction equipment, which help support the industrial commons needed for dual-use and defense industries.

Industries such as furniture, cosmetics, sporting goods, wind turbines, wood products, cement, and toys are not national power industries, in part because losing them would not create any serious vulnerabilities to China. Kids might not have many toys, but we can live with that. The same is true for virtually all nontraded sectors, which are, by definition, not subject to competition from foreign imports (e.g., barber shops, personal service providers, etc.)

It is time for the United States government to craft a coherent power industry strategy.

Because maintaining allied strength in national power industries is critical, policymakers must jettison the deeply held view that governments should not pick winners and that market outcomes are Panglossian in nature—the best of all possible worlds. Markets might optimize per-capita GDP growth (although even here, there are market failures that suggest some government intervention is needed to maximize per-capita GDP growth), but only by luck and happenstance will this generate the power-industry capabilities the United States needs to maintain superiority over China. There is no inherent reason why the United States will produce telecom equipment, semiconductors, electronic displays, circuit boards, and more.

And even with robust defense spending, weakness in dual-use and enabling industries would undermine the defense sector, requiring massively larger defense budgets to produce the weapons systems the Department of Defense (DOD) needs in specialized factories with limited economies of scale. Markets, for all their value, are happy to enable the production of financial advisors, legal services, and high-end garments, while allowing dual-use sectors to wither and die in the face of subsidized Chinese production. This is true even with a robust national manufacturing strategy, which might end up with more production of shoes, golf clubs, and two-by-fours, but not optics, machine tools, and lasers, which weapons systems need.

Policymakers already understand this when it comes to the production of weapons such as fighter aircraft and guns. While private companies make these, they do so under government contracts. It’s time to extend that thinking to dual-use and enabling industries too—not that in all or even most cases would these industries be supported by government contracts. But in all cases, there should be well-crafted and effectively implemented government strategies to ensure continued dynamic capabilities in national power industries.

The implications of this simple yet profoundly important change in thought are significant. In short, it is time for the United States government to craft a coherent power industry strategy. No, this does not mean state socialism or crony capitalism and Solyndra. No, it does not mean corporate welfare. But it does require embracing the concept of national power industry strategy, some of which, as described ahead, can be built on the insights from the scholarly and professional literature on corporate strategy.

Today’s Historical Turning Point

Despite what some free-market conservatives argue, America’s economic and trade policies have not been consistent since the founding of the Republic. Rather, key inflection points have occurred, leading to new beliefs, institutional arrangements, and policies. And each time, America’s leaders have made the right choice, although often through trial and error and incremental adjustments. But the transformations have been made that have enabled a more powerful and wealthier nation.

It’s worth reviewing these historical pivots. From its colonial founding until the second war with the British (the War of 1812), American leaders largely saw the colonies and then the nation as a peripheral, natural resource economy, dependent on Britain for trade in manufactured goods that were to be paid for through exports of staples (wood, fish, tobacco, furs, etc.). After the revolution, some, such as Alexander Hamilton, recognized that this was fundamentally a relationship of dependency. That is why he “believed that in industry lay our great national destiny.”[9] He did not want America to remain a “hewer of wood and drawer of water.” Indeed, he argued that government should “cultivate particular branches of trade ... and to discourage others.”[10] That’s why America’s first successful manufacturing firm, the Society of Useful Manufacturers, was funded by the state of New Jersey and leading American financiers that Hamilton convinced to fund it.

Even Jefferson embraced national developmentalism, including protective tariffs.[11] As president, his goal was to repay the national debt and then use the revenues to fund “rivers, canals, roads, arts, manufacturers, education and other great objects.”[12] He “encouraged new branches of industry that may be advantageous to the public, either by offering premiums for discoveries, or by purchasing from their proprietors such inventions as shall appear to be of immediate and general utility, and rendering them free to the citizens at large.”[13]

But it wasn’t until the shock of the war of 1812 that a true consensus for industrial development emerged. Indeed, in 1816 Jefferson wrote, “You tell me I am quoted by those who wish to continue our dependence on England for manufactures. There was a time when I might have been so quoted with more candor, but within the 30 years, which have since elapsed, how are circumstances changed!”[14]

Jefferson was a man who was willing to change his thinking when conditions required doing so. Indeed, the war broadened and heightened calls for more efforts to develop American industry. Henry Clay and other Whigs devised “the American System,” consisting of tariffs to protect and promote industry; a national bank to foster commerce; and federal subsidies for roads, canals, and other domestic improvements. The latter also involved subsidies to targeted industries, including at the state government level. When running in 1832 as a Whig, Abraham Lincoln stated, “[M]y politics are short and sweet, like the old woman’s dance. I am in favor of a national bank ... in favor of the internal improvements system, and a high protective tariff.”[15] These changes enabled the development of American industries, many driven by waterpower, including textiles, muskets and rifles, shipbuilding, and others.

The next pivot was the Civil War. This time the core change domestically was whether the United States would fully embrace industrialization to become a world power, with the centralization of power and high tariff walls that entailed. Or would it allow industrialization to occur at its own pace with much of the U.S. economy maintained as an agrarian and plantation export economy. Southern plantation states opposed this mission and the institutional changes that it entailed, in part because it meant higher prices for what farmers consumed and reduced overseas markets for what they sold. The Civil War made the choice inexorable, and with the victory of the Northern States, the United States proceeded to industrialize at a rapid rate behind a high tariff wall and with the support of defense industry purchases.

Indeed, for the rest of that century, the United States was the China of its day: an economy in which industrialization was everything and growth was off the charts. This led European countries to despair. As David Kedrosky wrote:

Frederick Arthur McKenzie’s The American Invaders and WT Stead’s The Americanization of the World (both 1901) were just two of an avalanche of publications advertising the rot of Britain and the inevitability of its supersession by its youthful, vigorous former colony. Economists cast about for something, or someone, to blame.[16]

He went on to cite leading British economists Alfred Marshall, who sounded the alarm in 1903 (wish that we had more Alfred Marshalls today in the United States):

Sixty years ago England had leadership in most branches of industry. It was inevitable that she should cede much to the great land which attracts alert minds of all nations to sharpen their inventive and resourceful faculties by impact on one another. It was inevitable that she should yield a little of it to that land of great industrial traditions which yoked science in the service of man with unrivalled energy. It was not inevitable that she should lose so much of it as she has done.[17]

The next major pivot came with the American victory in WWII and then the rise of an aggressive and expansive Marxist-Leninist Soviet Union. After WWII, the forces for returning to the pre-war status quo were strong. In 1946, Truman’s State of the Union speech called for bringing most troops home and demobilizing.[18] And his economic policy was to continue New Deal social programs but embrace Keynesian cycle management.

But it was only after Soviet expansionism into Eastern Europe, the development in 1947 of the “Truman Doctrine,” a few years later Stalin giving the green light for Kim Il Sung to invade South Korea, and seven years later the Soviets launching Sputnik that America responded with overwhelming force. The United States chose to assume leadership of the free world, in part because of the fall of the British Empire and the benefits that came with hegemony, but also become someone needed to stop Soviet expansionism.

Indeed, NSC-162-2, a new national security policy generated through the Solarium project initiated by President Eisenhower, argued for a new approach to national policy to address the Soviet threat.[19] Among other things, it called for, “in the face of the Soviet threat, the security of the United States requires … A mobilization base, and its protection against crippling damage, adequate to insure victory in the event of general war.”

This new strategic approach meant several things: first, the rejection of tariffs and the embrace of free trade and global integration, in part to ensure more stable democracies around the world aligned with the United States, because at home, the Cold War meant unprecedented massive funding for science and technology.

Second, starting in WWII, the federal government dramatically ramped up its support for advanced industry. By the early 1960s, it spent more on research and development (R&D) than the rest of the world combined.[20] That fueled an enormous array of breakthroughs, including computers, semiconductors, jet aviation, lasers, numerically controlled machine tools, satellites, relational databases, and of course, the Internet. Indeed, NSC-162-2 called the United States to “[c]onduct and foster scientific research and development so as to insure superiority in quantity and quality of weapons systems, with attendant continuing review of the level and composition of forces and the industrial base required for adequate defense and successful prosecution of general war.”[21]

Starting in WWII, the federal government dramatically ramped up its support for advanced industry. By the early 1960s, it spent more on R&D than the rest of the world combined.

Turning points are hard. There is a reason societies establish routines, fixed institutions, and common rules. Changing them is hard. Vested interests oppose them. Few experts have the intellectual fortitude to challenge their own frameworks. Voters get comfortable with the status quo. And democratic politics makes change hard. But as history shows, when the disjuncture between external reality and internal frameworks and approaches becomes wide enough, America has been able to successfully embrace pivot points. Perhaps the most important question facing the nation today is, does the U.S. political economy have the capability, absent a military conflict with China, to make the needed changes? The final part of this report examines this question.

America’s Current Techno-Economic and Trade System and Why Support for It Persists

After the Soviet threat evaporated in the early 1990s, American leadership assumed that the United States was not only in a unipolar moment, but that, as Francis Fukayama argued, history itself had ended.[22] In other words, Western liberal democratic capitalism had triumphed over all. If he had in fact been correct, there would be no need to write this report, as China would be well on the way to a free-market democracy. But also, he and most others were so enthused by the collapse of the Soviet Union that enthusiasm overrode reality.

As a result, the ideological and policy ideas that went with this phase have not only remained as core to U.S. techno-economic and trade governance, but at least until recently, become even more embedded in American thinking. Since America won, there was and is no real historical turning point other than one that reinforced the primacy of the U.S. system. Four core ideas remain.

First, it is America’s role to advance free trade and globalization even if it was not in our narrow interest. Free trade, especially other nations selling to America, helped ensure that they entered the American orbit and not the Soviet one or remained unaligned. The U.S. economy was so strong that it could afford uneven trading arrangements. Indeed, until the early 1970s, the U.S. economy enjoyed trade surpluses. Later, as those surpluses turned to trade deficits and the United States became the importer of last resort, the view was that the U.S. economy was still the strongest, and besides, trade deficits not only didn’t matter, but they were also a reflection of economic strength. Ahh, the power of wishful thinking.

On top of that was the pervasive idea held by the foreign policy establishment and economists that not only was all trade good, but so too was the movement of U.S. business operations overseas. Indeed, a 2013 survey of Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) members found that 73 percent believed that the U.S. economy would be strengthened if more U.S. companies set up operations overseas. In contrast, just 23 percent of the U.S. public believed this.[23] One is reminded of William Buckely’s quip that he would rather live in a society governed by the first 2,000 names in the Boston phone book than one governed by 2,000 Harvard faculty members.[24] Also, 52 percent of CFR members predicted that China would become more democratic by 2023 and 34 percent thought China would be a key future ally by then. President Xi, did you see this survey? If so, why did you not go along with the CFR folks?

As surpluses turned to trade deficits and the United States became the importer of last resort, the view was that the U.S. economy was still the strongest, and besides, trade deficits not only didn’t matter, but they were also a reflection of economic strength.

Following in the intellectual path set by classical economist David Ricardo, the consensus view became that trade was always win-win, and there was a comparative advantage wherever a nation’s industrial structure was based on—unless distorted by suboptimal government policies—inherent natural comparative advantages. Not only was there no reason for government to alter “natural” industrial structure, but it was also welfare reducing to do so. Moreover, to the extent there were foreign deviations from free trade, they were seen as barriers and distortions that hurt the countries putting them in place, not as attacks on U.S. companies and the U.S. economy. In this regard, free trade is seen as a natural phenomenon producing natural and superior results. The fact that most of the rest of the world neither believed nor practiced this only reinforced the messianic mission of America to teach the heathens the errors of their ways and convert them to the free trade religion.

Second, what ultimately buttressed this the way free booze buttresses an alcoholic was the fact that the U.S. dollar was the reserve currency. The dollar was accepted everywhere, and ultimately, if the United States needed more dollars, unlike any other nation, it could simply print more. This is termed the “exorbitant privilege” that let the United States run massive trade deficits for decades. In realty, it was not a privilege but an albatross around America’s neck, allowing policymakers to be indifferent to structural trade deficits. With such massive trade deficits, any other nation would have had to devalue its currency and grow its exports and reduce imports. But not the United States. And so, U.S. manufacturing, including national power industries, shrank. And because there was no real consequence to this—foreign nations continued to pour money into the United States, in part to keep their currency values low and exports high—it was easy for American pundits and experts to ignore and deny the decay of American power industry capabilities. Indeed, most to this day still defend the reserve currency status of the dollar as a key source of national power, instead of what it really is: a cancer on national power industry competitiveness.

Third, because the techno-economic power imbalance between the United States and the Soviets was so large, there was no need for a strategic industry policy. The Soviets might have had a peer-competitor military, but they by no means had a peer-competitor set of national power industries. And one reason was that Soviet command economics, unlike Chinese state capitalism, was incredibly limiting. Soviet Gosplan was in fact a central planner and allocator of goods and services.

Fourth, science and technology proceeded from funding to scientists to pursue basic research in whatever areas they chose (what FDR science advisor Vannevar Bush laid out as the linear model of basic science to commercial production) and company-funded research based on market forces alone. This meant that just as “computer chips, potato chips what’s the difference?” prevailed in economic thinking, “astrophysics, quantum physics what’s the difference?” prevailed in science funding. In other words, the United States was so far ahead of other nations in science that it had the luxury of funding a large share of the world’s basic, exploratory research that other nations used to build their advanced industry export economies.

As such, neoclassical, non-goal-oriented economic policy became accepted as all-time truth. It was true everywhere and always. Short-run efficiency generated from market actors operating in response to market-determined price signals was the lode star. Externalities, with perhaps the exception of pollution, were few and far between, and government’s efforts to intervene in this natural, indeed beautiful, process were, by definition, welfare-reducing.

This truth still dominates U.S. expert, pundit, and policymaker thinking. An emblematic example is a Washington Post op-ed excoriating President Trump’s conditioning CHIPS Act grant funding to Intel on the federal government getting an ownership share. Yes, this was a bad decision, but not because it violated free-market dogma, but because it ultimately weakened Intel, clearly a power industry company.[25] The Post’s statement is a perfect reflection of what current U.S. consensus is regarding techno-economic and trade policy where power industry concerns are nonexistent:

This deal is the culmination of America’s resurgent interest in industrial policy, the same interest we always develop when we sense a challenge to our global economic dominance. Whenever we spot a new competitor on the horizon, we look wistfully at China — or Germany, or Japan — and wonder if it’s a mistake to let the market decide what America produces. Maybe we should learn a lesson from the competition and let the government, with its deep pockets and longer time-horizons, take a bigger role in shaping the economy.

This particular policy also risks distorting the free-market system that has delivered better results for America, and the world, than any state-managed competitor has ever achieved. And it is unlikely to fix the deep problems with Intel, which have been decades in the making.

There is an argument for industrial policy in strategically vital products. The United States does not want to source critical defense inputs from geostrategic rivals. But that argument only works if you make three dubious assumptions: that the government can confine its efforts to strategically important industries (rather than, say, bailing out failing automakers with politically powerful unions); that it can spend the money wisely (rather than wasting huge sums on efforts that sounded better to planners than to buyers); and that the companies that find themselves showered with money will use it to turn themselves into globally competitive superstars, rather than to maintain a lackluster operation thanks to the subsidies.[26]

A few years ago, this op-ed would have been exactly the same, but without the reference to the need for “strategically vital products.” At least now elite discourse has to include a passing reference to this, before it then breezes on praising the wonders of the free market.

There is one final component of the America’s techno-economic and trade doctrine, one that did not emerge until the fall of the Soviet Union: American hubris.

In its close, the op-ed at least considers that it might be necessary for the United States to have strong national power industries, but the authors still couldn’t help themselves and fall back into conventional thinking, claiming that the old model actually works when it comes to national power industries. Government, it claims:

can also work harder on improving infrastructure and fixing government policies that drive up manufacturing costs, such as land-use regulations and taxes. But the United States should not try to beat China by becoming China. We should compete the way we always have: by relying on the free enterprise system that has served us so well for so long.[27]

If this is not a rejection of the need for a doctrinal shift in response to an historical turning point, I don’t know what is.

There is one final component of the America’s techno-economic and trade doctrine, one that did not emerge until the fall of the Soviet Union: American hubris. At least during the Cold War, leaders on both sides of the aisle were worried about the Soviet challenge, not just militarily but also technologically, especially in the 1950s and 1960s as Soviet space and nuclear technology advanced. In hindsight, the technology threat was overstated, but nonetheless, policymakers remained apprehensive, ever focused on maintaining our lead.

Now, absent that threat, America suffers from what Chinese political economist Heng-Fu Zou calls “status-quo-based optimism.”[28] In other words, too many U.S. experts and policymakers still see the world as it was from 1990 to the mid-2000s when the belief was that United States was preeminent in virtually everything. Communism had been defeated and was consigned to the dustbin of history. China was a poor, developing market economy, not a development-oriented Marxist-Leninist dictatorship. And emerging signs that China might be becoming a peer competitor were almost completely ignored by the expert class, so much so that individuals and organizations that tried to issue warnings were dismissed as cranks. Case in point: the U.S. China Economic and Security Review Commission, an entity created by Congress as a sop to those worried about the effects of letting China in the World Trade Organization (WTO). For years, the view in Washington was that these were a bunch of crazed China hawks and it was largely frowned upon for experts to testify in front of this commission.

Because the United States had vanquished its foes and stood tall and unopposed (except by jihadists that turned airplanes into missiles), that meant, by definition, that the current techno-economic and trade system was optimal. It had led to the prosperous and strong America. No one could touch us. So why challenge what had worked so well?

This is perhaps the driving factor in why so many in the expert and political classes are so closed to considering new techno-economic and trade frameworks. The old/current system worked great. Why fix it if it ain’t broke?

Accepting realities would mean a weakening of the foundations of the tripartite American techno-economic and trade doctrine: free trade, free markets, and reserve currency. That doctrine, and the professional reputations built upon it, must, at all costs, be defended.

And it is also why so many in the expert and political classes are almost completely impervious to data suggesting that reality no longer exists, especially the increasingly obvious Chinese techno-economic rise and the concomitant American decline, as well as Xi’s Marxist-Leninist global hegemonic aspirations. Reams of data showing China’s techno-economic rise are ignored or denied, as is data showing U.S. decline. Well, the data must be wrong. Or China is different. Or the data doesn’t apply to the United States. Besides, we all know that China has a host of short-term business cycle challenges (e.g., housing glut), so no need to consider structural change. A bit more science spending, some regulatory tweaks, and some more high-skilled immigration and all will be ship-shape.

Accepting these realities would mean a weakening of the foundations of the tripartite American techno-economic and trade doctrine: free trade, free markets, and reserve currency. That doctrine, and the professional reputations built upon it, must, at all costs, be defended.

In other words, the consensus among the elite class is that the current system suffices. However, what is striking about past fundamental pivots in American techno-economic and trade systems is that all were in response to war: the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812; the Civil War; and WWII and the Korean War. Before each of these conflicts, the consensus view was for the then current system. Few policymakers and elites had any real desire to change, and those that did were in the minority with no real power. It was the shock and destruction of war that made the rejection of the old system and the embrace of a new system a virtual requirement.

Today, without a great-power war to spur change, there is little that is doing so. The Chinese national power trade attacks are not major battles, but rather a constant drip-drip of allied and U.S. losses that are either overlooked or rationalized as inconsequential. Better to defend the tripartite system of free trade, free-market economics, and reserve dollar and attack or ignore anyone who has the temerity to challenge it. Better to attack Trump as a clueless protectionist rather than to acknowledge that his concerns, if not necessarily his policies, reflect a new reality.

It is possible that a People’s Republic of China (PRC) invasion of Taiwan might produce such a motive force. But it might not because U.S. leaders and the public could just give up and either not intervene or intervene but quickly withdraw after casualty numbers go up and missile stocks go down. If the PRC were smart and understood America, it would bide its time (it can no longer hide its light) until its GDP and power industry and military capabilities significantly outweigh those of the United States and the West. If it invaded then, even if the shock of war and defeat were enough to highlight the defects of the current system and motivate the embrace of a new one, it would be too late to do anything meaningful. U.S. and allied techno-organizational capabilities for renewal, including an existing advanced industrial base, would be below what is needed. As discussed ahead, the barriers to entry in most of these complex and capital-intensive industries would be too high. Even if the American populace and the elite class came together with a massive Sputnik-like movement and responded, the amount of effort and money needed to rebuild would be enormous. And so the techno-economic war would be over, and the United States would have lost most of its national power industry capabilities with virtually no way to get them back, akin to the United Kingdom after WWII. All the United Kingdom can do now is show nostalgic TV shows on BBC about when Britannia ruled the world.

Box 1: Britain’s Failure to Grasp Its Turning Point

Like America, Britain faced a turning point during and after WWII, but unlike the United States, it failed to successfully turn, resulting in the permanent (at least to today), long-term deindustrialization and decline of the United Kingdom.

In his masterful book The Audit of War: The Illusion and Reality of Britain as a Great Nation, British historian Correlli Barnett documented the failures and why.[29] Like noted industrial historian Alfred Chandler, Barnett argued that British industry did not succeed in emulating American mass production and the management that went along with it. As Elbaum and Lazonick wrote:

Successful capitalist development in twentieth century German, Japan and the United States demonstrates the ubiquitous importance of the visible hand of corporate bureaucratic management. To meet with international challenge, British industries required transformation of their strategies of industrial relations, industrial organization, and enterprise management. Vested interests in the old structures, however, proved formidable obstacles to the old transition from competitive to corporate modes of organization.[30]

The result was significant lags in productivity and quality of manufactured goods, especially compared with Germany and the United States. And in many areas, Britain was completely dependent on other nations. For example, during the war, Britain was totally reliant on the United States for over 20 kinds of machine tools it had never been able to make itself.[31]

Some of this was due to poor management; many firms were still family owned and modest in size. Much of it was due to strong labor unions and their utter opposition to the kinds of industrial organization and job change that would be required to boost efficiency to be able to compete internationally.

It would have been one thing if Britain were losing its old industries but at least gained the new ones, such as chemicals, electronics, and aerospace. But it failed there as well, in part because of the persistence of the craft industry, as opposed to mass production—and also because the government spent so little on R&D. At the same time, the schools and university system, unlike that of Germany and the United States, focused on traditional education, especially learning the classics, and neglected both skilled-trades education and STEM education.

It wasn’t that certain groups and individuals in government were not aware of these challenges. Some were and proposed fairly far-reaching industrial policy changes that, if implemented, would have certainly reduced the scope and scale of deindustrialization and lack of progress in emerging science-based industries.

But at a political economy level, there were three forces that meant failure. The first was the long-standing British free-market ideology, especially among economists that eschewed any more than minimal government role in restructuring industry. And the Conservative Party’s top priority was on “sound finance” and free trade. And many economists opposed scrapping out-of-date industrial machinery until that had been completely depreciated and was no longer working.

The second was the rise of the Labour Party and its massive embrace of what Barnett has called “The New Jerusalem”: the idea that the state would provide a new almost utopian life for British citizens through public spending. Based in part on the 1942 “Beverage Report,” which called for “cradle to grave” public support, including national health insurance, massive housing spending, and more money on education, the new Labour government under Atlee saw this as its overwhelming task to implement these wartime proposals. Indeed, the view of many was that Britain deserved this after its all-out fight to defeat Hitler. As Barnett wrote, “New Jerusalem was their [British ‘enlightened’ establishment Party officials] high-minded gift which they proceeded successfully to press on the British people between 1940 and 1945, with far-reaching effects on the British people’s postwar chances as an industrial power struggling for survival and prosperity.”[32] This massive new social services spending campaign crowded up virtually all needed public investment to be able to compete. It was not that the officials didn’t know that this would cost a lot of money. Rather, as Barnett wrote, they pursued this vision “on the best romantic principle that sense must bend to feeling, and facts to faith,” much like American conservatives and liberals push for tax cuts and spending increases, respectively, even when the till is empty.[33]

And ironically, the factor that held both the Conservative and Labour views together was the still prevalent individualism over communitarianism. School reform was based on freedom for the individual, rather than on what would boost national power. Spending was based on satisfying immediate needs, rather than boosting national power in the medium term. As a result, national investment was minimal, just one-third of post-war Germany levels.

In summary, Barnett stated, “If Britain after the war was to earn the immense resources required to maintain her cherished traditional place as a great power and at the same time to pay for New Jerusalem at home, she had to achieve nothing short of an economic miracle. Such a miracle could only be wrought through the transformation, material and human, of her essentially obsolete industrial society into one capable of triumphing in the world markets of the future.”[34] Had all the most powerful groups and institutions in that society enthusiastically been willing to throw themselves behind the process of transformation, it still would have been difficult enough to achieve, given the scale of inherited problems. But instead of such willingness, there existed massive inertial resistance to change, which was so manifest in the history of Briain as an industrial society; a resistance that not even the shock of war had proved strong enough to budge more than a little.[35]

What does this all mean then? First and foremost, it means that the core challenge for America is wholesale abandonment of the post-war free-trade comparative advantage, free-market, and reserve currency doctrines and practices, and their replacement with doctrines and practices fitted for U.S.-China power industry conflict, as discussed ahead.