Rostow’s The Stages of Growth Needs a Sixth Stage

In 1960, Walt Rostow, an MIT economist and advisor to Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, published The Stages of Growth: A Non-Communist Manifesto. In it, he outlined five stages of economic development that nations would ideally progress through, with the United States already having reached the penultimate stage. Given the decline of some advanced economies today, he should have laid out a sixth stage.

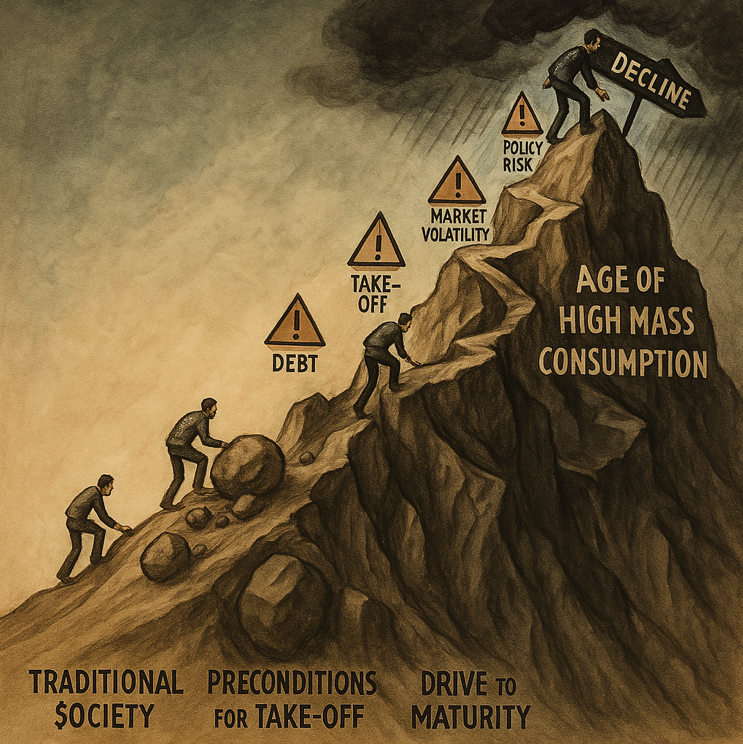

Rostow’s Five Stages of Growth

- Traditional Society: This stage is characterized by a primarily agricultural economy with limited technology and rigid social structures. Economic change is minimal, and most people engage in subsistence farming. Thankfully, few countries remain in this stage today—perhaps South Sudan or Burundi—but many were there in 1960.

- Preconditions for Take-off: Here we see the beginnings of industrialization, marked by investments in infrastructure, education, and new technologies. Entrepreneurial activity increases, and the economy begins shifting away from agriculture to other sectors. Many developing nations, such as Uganda, Senegal, and Rwanda, are in this phase.

- Take-off: This phase features rapid industrialization and self-sustaining economic growth, often driven by a few key industries. Investment exceeds a critical threshold. This described South Korea in the 1960s and China in the early 2000s.

- Drive to Maturity: The economy diversifies, and technology becomes more broadly applied across all resources in this stage. Economic development continues, becoming more automatic through high rates of saving and investment. Many Eastern European nations, and arguably China, appear to be here today.

- Age of High Mass Consumption: Here, we see the economy become consumer-oriented, characterized by high living standards and growth driven by consumption and services. This described the United States, Western Europe, Korea, and Japan—at least until recently.

The Flaws of Stage Five

At the time, Rostow’s model was compelling. It implied that, with patience and commitment to capitalism, less-developed countries would inevitably become rich—and could resist the temptations of Soviet communism. However, he gave insufficient attention to the cultural and institutional barriers that have kept many nations stuck in stages one or two.

Moreover, his conception of stage five was especially flawed. Rostow, like many contemporaries, assumed U.S. dominance was unassailable and paid little attention to global competition. Along with Harvard sociologist Daniel Bell, he embraced the mistaken notion that services represented a more advanced stage of development than manufacturing. And like most at the time, he drank the Keynesian, demand-side Kool-Aid, wrongly assuming that consumption was the primary driver of growth.

Introducing Stage Six: Bloated Decline

It’s time to add a sixth stage, “Bloated Decline,” because for some nations, stage five contains the seeds of its own regression: deindustrialization, overconsumption, underinvestment, and productivity stagnation. Development economics needs a rethink. Nations at the peak—high mass consumption—can and do fall from the commanding heights.

Stage Sixers are not hard to spot. The United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia have clearly passed their prime. All three have experienced steep deindustrialization and lost ground in advanced industries. All face productivity stagnation and low capital investment rates as investors chase safer returns through speculation and capital-light business models. All have prioritized social policies, especially climate and DEI, over economic ambition. And all exhibit what political economist Mancur Olson described as sclerosis: the buildup of self-interested political coalitions that block the creative destruction necessary for continued progress.

Other nations, such as France, Italy, the Netherlands, and even Germany, are close to becoming Stage Sixers.

The United States still hovers at stage five, seemingly uncertain whether to rest or keep climbing. On one side are green de-growthers and red redistributionists, eager to settle into a soft, selfish, socialist economy—one that shuns growth in favor of soaking the rich. On the other side are center and right-leaning growth advocates, including many in the Trump administration, but their brand of “small government protectionism”—cutting public investment while raising tariff walls—lacks the firepower needed to propel the country upward.

The Myth of Reaching the Summit

The core flaw in Rostow’s model is the assumption that stage five represents the ultimate destination. Nations are supposedly good to go once they reach that peak. They can look down smugly on those still climbing (China, for instance) and say, “Good luck, poor bastards. We’ve made it. Now we can relax.” But anyone who’s climbed knows that when you reach the top, you rest briefly, eat some trail mix, take a few pictures—and then keep moving on to the next peak.

A better model sees no fixed stages and certainly no permanent peak, only a relentless push to go higher and higher, even if it means hard work and sacrifice. Leading innovation economist Joseph Schumpeter rightly likened innovation to navigating uncharted seas. Growth has no final destination; the voyage doesn’t end unless nations give up or fail.

Indeed, in a refined model, reaching a plateau cannot be the goal. Rising challengers—nations seeking to surpass the United States—will do everything they can to knock us from the summit. The Chinese Communist Party wants to reach stage five, not to enjoy the view with the U.S., but to send us tumbling down so it can continually press onward and upward.

Regression or Reinvention?

Perhaps there are two paths beyond stage five. One leads to regression, a stagnant, less competitive economy weighed down by complacency. The other points toward reinvention and progress: a future powered by mass automation and cutting-edge technologies. China is clearly pursuing the latter. Whether the United States wants that future and is willing to make the necessary sacrifices to achieve it remains to be seen.