Comments to the Bureau of Industry and Security Regarding Its Section 232 Investigation of Pharmaceutical Imports

ITIF is an independent 501(c)(3) nonprofit, nonpartisan research and educational institute that has been recognized repeatedly as the world’s leading think tank for science and technology policy. ITIF focuses on a host of critical issues at the intersection of technological innovation and public policy—including economic issues related to innovation, productivity, and competitiveness; technology issues in the areas of information technology and data, broadband telecommunications, advanced manufacturing, life sciences, and clean energy; and overarching policy tools related to public investment, regulation, antitrust, taxes, and trade. ITIF’s goal is to provide policymakers with high-quality information, analysis, and actionable recommendations they can trust. To that end, ITIF adheres to a high standard of research integrity with an internal code of ethics grounded in analytical rigor, original thinking, policy pragmatism, and editorial independence.

ITIF is pleased to offer these comments in response to the Department of Commerce Bureau of Industry and Security Request for Public Comments on Section 232 National Security Investigation of Imports of Pharmaceuticals and Pharmaceutical Ingredients.[1]

(i) the current and projected demand for pharmaceuticals and pharmaceutical ingredients in the United States

The U.S. pharmaceutical market is the largest globally, estimated at $643 billion in 2024 and expected to be $884 billion by 2030.[2] Among other factors, the demand is driven by an aging population and a rising prevalence of chronic diseases. Biopharmaceutical innovation is essential to maintaining U.S. leadership in health and competitiveness, especially as global rivals invest heavily in their own capabilities.

(ii) the extent to which domestic production of pharmaceuticals and pharmaceutical ingredients can meet domestic demand

ITIF’s 2023 Hamilton Index shows that the global biopharmaceutical industry experienced a 223 percent growth from 1995 to 2020 in nominal U.S. dollars, compared with 174 percent for global gross domestic product (GDP). The United States ranked first in the world for pharmaceutical production (28.4 percent of global production), followed by China with 17.4 percent.[3] Moreover, America’s new drug development has been substantially higher than that of the rest of the world. From 2014 to 2018, U.S.-headquartered companies produced almost twice as many new chemical or biological entities as European ones, and nearly four times as many as Japan.[4]

The United States has strong capabilities in pharmaceutical R&D and final drug production but, as point (iii) below describes, remains reliant on foreign sources for active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), the components in medications that are biologically active, directly contributing to the therapeutic effects used to treat, diagnose, or prevent diseases. Reshoring the pharmaceutical supply chain (i.e., building domestic manufacturing capacity for APIs) is a critical national security need.[5]

(iii) the role of foreign supply chains, particularly of major exporters, in meeting United States demand for pharmaceuticals and pharmaceutical ingredients

Foreign supply chains are essential to U.S. pharmaceutical access, particularly for APIs and generic drugs. In the United States, where nine out of ten prescriptions dispensed are for generic drugs, India supplies roughly 40 percent of those drugs.[6]

Data from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) shows that in 2019, only 28 percent of API manufacturers were based in the United States, while 72 percent were overseas—with 13 percent in China and 18 percent in India.[7] Four years later, in 2023, the U.S. Pharmacopeia further assessed U.S. dependence on foreign API based on its Medicine Supply Map. Based on the number of total active API drug master files (DMFs)—documents submitted to the FDA containing information about APIs, including identifying existing geographic locations that are manufacturing APIs—India accounted for 48 percent of API DMFs, China 16 percent, and the United States 9 percent.[8]

Heavy dependence on foreign sourcing for critical ingredients can leave U.S. pharmaceutical companies exposed to supply disruptions and quality control problems that could put the nation at risk of drug shortages.[9] In fact, 2024 saw a record number of drug shortages (323). Out of the 461 drugs listed in the 2019 World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) Essential Medicines List, FDA data shows that 1,079 API manufacturers worldwide make these drugs, with 15 percent in China, 21 percent in the United States, and 64 percent in the rest of the world. Three essential medicines have API manufacturers that are all based in China.[10] The focus should be on reducing over-concentration in any one region and building supply chain resilience through transparency, diversification, and targeted domestic capacity where security is at stake.

(iv) the concentration of United States imports of pharmaceuticals and pharmaceutical ingredients from a small number of suppliers and the associated risks

The United States relies on international suppliers for key drug ingredients and finished products, which creates significant vulnerability to supply disruptions caused by geopolitical tensions, trade restrictions, natural disasters, or quality issues. The United States has been losing domestic pharmaceutical manufacturing capacity, particularly for manufacturers of APIs.[11] Production subsidies, cheaper labor, and less-stringent environmental regulations have attracted API manufacturers to build plants overseas. In congressional testimony in October 2019, Dr. Janet Woodcock, former director of the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) at the FDA, explained how the FDA is supporting the growth of advanced manufacturing to reduce U.S. dependence on overseas manufacturers, improve the resilience of American manufacturing, and mitigate the potential risk of drug shortages in the United States.[12]

In September 2022, the Biden administration announced new investments to support the resilience of domestic pharmaceutical manufacturing, committing $40 million to expand the role of advanced manufacturing, namely, biomanufacturing—the use of biological systems to produce drugs—to support domestic production of APIs, antibiotics, and other critical materials needed to produce essential medications.[13] In November 2023, the administration took further measures to reduce reliance on high-risk foreign suppliers by invoking the use of the Defense Production Act to expand the Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS’s) authority to invest in domestic manufacturing of essential medicines. HHS was directed to commit $35 million to efforts to bolster the strength of the domestic supply chain for essential medicines.[14] A recent report by the American Society of Health System Pharmacists (ASHP) found a record 323 active drug shortages in the United States in the first quarter of 2024, surpassing the 2014 record of 320 drug shortages. The American Hospital Association (AHA) recommended Congress enact legislation to diversify manufacturing sites and sources for critical pharmaceutical ingredients.[15] ITIF calls for bolstering domestic production capacity where market failures exist, particularly in essential generic and injectable drugs, while maintaining access to competitive global sources.

(v) the impact of foreign government subsidies and predatory trade practices on United States pharmaceuticals industry competitiveness

The Trump administration should focus first and foremost on the mercantilist practices that China has pursued to gain competitiveness in the global biopharmaceutical industry, policies that have delivered significant dividends for it (as they have in many other high-tech sectors).[16] For instance, from 2002 to 2019, China increased its global share of value-added pharmaceuticals output from 5.6 percent to 24.2 percent.[17] (Over that same period, the United States’ share of global value-added pharmaceuticals output fell from just under 38 percent to 27.7 percent, a relative decline of over 25 percent.) From 2010 to 2020, 141 new drug and biotech companies were launched in China, doubling the figure from the previous decade.[18]

Certainly China has gained competitiveness in the sector in part through well-constructed innovation strategies. As part of the 13th Five-Year Plan (2016–2020), China’s Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) released a Biotechnology Development Plan outlining biotech priorities and goals. The plan emphasized biotech as key to China’s economic growth, supported the construction of research centers for innovative R&D and high-tech science parks, and urged industry players to enhance the originality of their drugs and devices.[19] China’s most recent Five-Year Plan (the 14th, covering 2021 to 2025), promotes the continued development and expansion of the industry, seeking to promote the integration of biotech and information technology (IT), accelerate the development of biotech and pharmaceuticals, and increase the size and strength of China’s bio-economy.[20] China has also significantly expanded research and development (R&D) investments in the sector. In 2022, China’s National Natural Science Foundation (NSSF) increased its research funding to encourage exploration and innovation, awarding 51,600 grants for a total of CNY 32.699 billion (nearly $4.5 billion), up from CNY 31.2 billion ($4.2 billion) in 2021.[21]

But the growth of China’s biopharmaceutical industry has been significantly abetted by mercantilist practices such as intellectual property (IP) theft, preferences for domestic entities, and industrial subsidization.

Indeed, there have been numerous reports of Chinese biomedical researchers working at U.S. universities, often on National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants, taking the IP that their labs develop back to China.[22] For example, in 2020, the U.S. Department of Justice charged the chair of Harvard University’s Chemistry and Chemical Biology Department, Charles Lieber, with aiding China with “one count of making a materially false, fictitious and fraudulent statement” regarding his work with organizations tied to the Chinese government, while on NIH funding.[23] Also in 2020, Ohio citizen Yu Zhou was sentenced to prison for conspiring to steal trade secrets concerning the research and treatment of different medical conditions, including cancer, from the Nationwide Children’s Hospital’s Research Institute to sell to China.[24]

Moreover, Chinese state-sponsored actors have targeted biopharma firms for IP theft, including through cybertheft and rogue employees.[25] That theft is sometimes through direct means whereby scientists working at U.S. biopharma companies engage in IP theft and then transfer it to China. In 2018, Yu Xue, a leading biochemist working at a GlaxoSmithKline research facility in Philadelphia, admitted to stealing company secrets and funneling them to a rival firm, Renopharma, a Chinese biotech company funded in part by the Chinese government.[26] In October 2023, intelligence chiefs from the Five Eyes countries—Australia, Canda, Britain, New Zealand, and the United States—accused China of IP theft in sectors including biotechnology.[27]

As the National Security Commission on Emerging Biotechnology wrote in its April 2025 report, “Charting the Future of Biotechnology,” “The CCP lavishes its chosen domestic firms with subsidies and preferential regulatory treatment that advantage them at the expense of foreign competitors.”[28] To the latter point, China puts it thumb on the scale by favoring Chinese firms in drug safety and efficacy reviews and national drug selection, preferring domestic suppliers over foreign ones.[29] For example, the National Medical Products Administration (NMPA) has given priority review to innovative medicines produced in China over those produced outside China.[30] China has also localized testing requirements for biologics testing and quality testing of imported ingredients, which adds to the cost and delays the release of innovative drugs.[31] Moreover, while drugs are on the approved list for foreign direct investment, Chinese governments encourage foreign biopharmaceutical companies to form joint ventures if they want their drugs more easily put on the government list of drugs to qualify for reimbursement or receive other benefits.[32] As the Shanghai American Chamber of Commerce wrote, “Adopting a minority position as an MNC (multinational company) could create increased market competitiveness and commercial opportunities and engender more favorable government treatment.”[33] Similarly, in exchange for investing in China, provincial governments tout their willingness and ability to help firms gain regulatory and market approval.[34]

China devotes billions of dollars in state subsidies to prop up companies that would not withstand normal market forces. In recent years, the Chinese government has funneled government funds to supposed “private” entities in order to avoid charges of government subsidization—which is actionable under the World Trade Organization (WTO) agreement. This is why the United States Trade Representative’s (USTR’s) office recently sent 70 questions to the WTO about Chinese subsidies, including in biotechnology.[35] As a result, it is not readily clear how much financing for China’s biotech sector has come from government or is really from subsidies rather than commercially guided investments. Nevertheless, Chinese government subsidies to its biopharmaceutical sector count in the billions and billions of dollars. For instance, in August 2024, Shanghai city alone pledged $4 billion in subsidies for biomedicine companies conducting clinical trials in the city.[36]

The United States should also ensure that the FDA has adequate funding to effectively inspect Chinese facilities producing drugs and APIs for U.S. consumption. According to the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) in a 2016 report, of 535 of Chinese facilities subject to FDA monitoring, as many as 243 were not inspected between 2010 and 2016.[37] Moreover, according to the GAO, “FDA does not know whether or for how long these establishments have or may have supplied drugs to the U.S. market, and has little other information about them.”[38] Better inspection and enforcement has several benefits. Besides improving safety, it means less production in China because many Chinese factories will likely fail inspections.

(vi) the economic impact of artificially suppressed prices of pharmaceuticals and pharmaceutical ingredients due to foreign unfair trade practices

When nations implement pharmaceutical price controls, they reduce pharmaceutical revenues, which then reduces investments in further R&D, limiting future generations’ access to new novel treatments needed to fight diseases such as cancer, Alzheimer’s, heart disease, and diabetes. Unfortunately, a majority of Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries implement some form of pharmaceutical price control on manufacturers on the basis that such measures will reduce drug prices for citizens.[39]

In 2023, using the RAND Corporation’s International Prescription Drug Price Comparison, ITIF examined prescription drug price differences between the United States and 32 OECD countries.[40] Of the 32 OECD countries with available data, all had lower prescription drug prices than the United States, which historically has not imposed price controls on its pharmaceutical sector.[41] Even after adjusting for GDP per capita, 30 countries still had lower prescription drug prices than the United States in 2018. (See table 1.) Luxembourg (403.1 percent lower than the United States), Turkey (246.8 percent lower), and Norway (229.3 percent lower) had the lowest prescription drug prices. Almost all OECD countries implement some form of drug price controls, leading to lower drug prices compared with an environment without price controls.

Table 1: Assessment of OECD countries’ GDP per capita-adjusted prescription drug price levels using RAND Corporation study (numbers over 100 indicate 2018 prices lower than the United States’)[42]

|

Country |

Price Index: |

Country |

Price Index: |

|

Luxembourg |

503.1 |

Lithuania |

182.7 |

|

Turkey |

346.8 |

Canada |

176.9 |

|

Norway |

329.3 |

Finland |

175.9 |

|

Ireland |

270.6 |

Czech Republic |

167.1 |

|

Australia |

249.9 |

Slovenia |

163.3 |

|

Sweden |

237.4 |

Italy |

158.3 |

|

Netherlands |

222.4 |

Greece |

155.7 |

|

Korea |

200.3 |

Portugal |

154.4 |

|

Belgium |

198.3 |

Spain |

152.8 |

|

Switzerland |

195.6 |

Japan |

150.0 |

|

New Zealand |

191.2 |

Poland |

140.9 |

|

Austria |

188.5 |

Latvia |

140.8 |

|

United Kingdom |

188.0 |

Hungary |

131.7 |

|

Germany |

187.3 |

United States |

100.0 |

|

Slovakia |

186.6 |

Chile |

75.0 |

|

Estonia |

185.3 |

Mexico |

54.9 |

|

France |

183.7 |

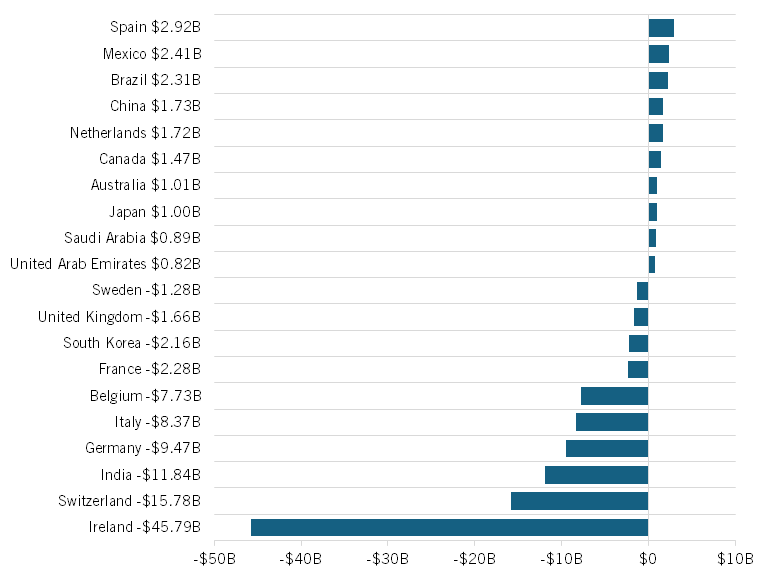

Many of these countries’ price controls contribute to a higher U.S. pharmaceuticals trade deficit than would otherwise be the case because they refuse to pay what they should for U.S. drug exports.[43] For instance, in 2024, the United States ran a $45.8 billion pharmaceuticals trade deficit with Ireland, a $15.8 billion deficit with Switzerland, a $9.4 billion deficit with Germany, a $8.4 billion trade deficit with Italy, a $7.7 billion deficit with Belgium, and a $2.3 billion deficit with France. (America’s largest pharmaceutical trade surpluses were with Spain ($2.9 billion), Mexico ($2.4 billion), and Brazil ($2.3 billion).) (See figure 1.) Much of this imbalance stems from the fact that drug exports from these countries generally earn market prices in the United States while reciprocal U.S. pharmaceutical exports to these countries encounter stringent drug price controls. (Ireland is unique from other European Union (EU) nations due to the concentration of U.S. (and other foreign) drugmakers’ subsidiary operations in large part due to the country’s historically EU-lowest corporate tax rates.) That said, the United States should make it a major focus of the present trade negotiations with EU member nations and other higher-income nations that they pay their fair share for innovative drugs; but this challenge should be addressed through trade negotiations, not through the implementation of blanket pharmaceutical tariffs.

Figure 1: U.S. pharmaceuticals trade balance with select countries, 2024 ($billions)[44]

India’s case is slightly different. In 2024, the United States exported $635 million of pharmaceutical product while importing $12.47 billion worth of product, generating a $11.8 billion trade deficit. The import figure is driven by India’s significant exports of generic drugs and APIs to the United States, while the lower levels of imports is driven by a combination of drug price controls and India simply being a lower-income economy in general. That said, India continues to remain on USTR’s Special 301 Watch List in part due to a litany of IP concerns, including expanded tests of novelty precluding pharmaceutical patent subject matter eligibility, ineffective mechanisms to resolve pharmaceutical patent disputes, and limited transparency to the entrance of generic or follow-on products upon an innovator’s patent expiry.[45]

Drug reimbursement in China has become increasingly centralized through the establishment of the National Healthcare Security Administration and the implementation of the National Reimbursement Drug List (NRDL), where drug price negotiation takes place.[46] China has been imposing steep drug price controls and favoring Chinese firms in national drug selection, seeking to build up its domestic industry capabilities.[47]

For example, in 2022, as in 2021, Chinese domestic companies were the source of most new drugs added to the 2022 NRDL, with some MNCs continuing to struggle to make deals with China’s National Healthcare Security Administration for their drugs.[48] In 2022, out of 147 drugs negotiated, 121 were added to the 2022 NRDL, with an average price cut of 60.1 percent. Seven orphan drugs were included in the 2022 NRDL, but the prices of those reimbursed drugs were far lower than their prices in other countries, with some reaching discounts of 94 percent during NRDL negotiation.[49] These price controls harm foreign firms more than Chinese firms with lower cost structures, and reduce the revenues of the global drug discovery innovation system.[50]

Compared to the United States and Europe, China’s IP environment for drug development has been decidedly weaker. For example, independent of patent protection, the United States and European Union both provide a period of marketing exclusivity (a.k.a., “regulatory data protection”) for a drug, as well as patent term extension to compensate for the loss of a patent term during the approval process. China does not, which effectively reduces the life of the patent by 40 percent, despite its TRIPS obligations under Art. 39.3, and despite the fact that their approval process is usually longer than the U.S. process.[51] China also uses procedures to invalidate patents based on heightened “enablement” and non-obviousness requirements. It also makes it more difficult than do the other IP5s (the United States, Europe, Japan, and Korea) for applicants to file supplement data with the patent application (post-filing data supplementation), thus invalidating more patents than would be the case if the patents were filed in the other IP5s.[52]

The United States recorded a $1.7 billion pharmaceuticals trade surplus with China in 2024, largely driven by the fact that China’s domestic industry is still evolving and there still remain many conditions/diseases for which U.S. providers still offer the best medicines. That said, there’s no doubt Chinese officials seek to achieve import substitution (replacing foreign imports with domestic production) in this as much as any other advanced-technology sector.

(vii) the potential for export restrictions by foreign nations, including the ability of foreign nations to weaponize their control over pharmaceutical supplies

There exists little doubt that China in particular seeks to identify bottlenecks or chokepoints in supply chains for critical inputs or products that it could use as leverage over foreign nations. This of course is particularly the case with regard to rare earth elements, where China presently produces some 60 percent of the world’s supply and processes 85 percent of them.[53]

The United States depends on China as the overwhelming source of its supply for some of the most commonly used medicines, with over 90 percent of ibuprofen, hydrocortisone, and acetaminophen, for example, coming from China.[54] Meanwhile, virtually all of the world’s facilities producing the active ingredient of amoxicillin (a common antibiotic) are currently found in China, Europe, or India.[55] Every year from 2014 to 2023, the United States sourced up to 28 percent of its total API inputs from China.[56]

(viii) the feasibility of increasing domestic capacity for pharmaceuticals and pharmaceutical ingredients to reduce import reliance

In terms of dollar value, the United States still produces the majority (53 percent) of the APIs it consumes.[57] Certainly the United States has the potential to increase that share. However, there are reasons why so much generic drug and API manufacturing occurs overseas. First, these tend to be commoditized, cost-driven, low-margin businesses that benefit from lower-wage labor found overseas. Second, laxer environmental regulations in countries such as China or India make refinement and processing of the chemicals going into APIs more economically feasible.

In situations such as the aforementioned case of amoxicillin, where virtually 100 percent of the U.S. supply is imported, raising tariffs on such imports would only serve to immediately raise prices for U.S. patients. Sure, eventually a higher tariff wall could in theory induce new entrants to enter the sector. But why would a foreign one enter the U.S. market when they have full control of the supply and the tariffs would only increase prices? A new domestic competitor might enter, but that process would take years for new U.S. facilities to be built (regulatory considerations and local and federal permitting, can add months, if not years, to construction). Moreover, if that domestic competitor could only economically compete behind the tariff wall, prices would end up being much higher for consumers. And the domestic competitor might not even enter if it felt that uncertainty in the sustainability of the tariff structure would preserve its long-term economic sustainability.

For these reasons, a far better strategy for the United States would be to develop a technology- and innovation-driven strategy to foster American enterprises’ ability to cost-competitively produce APIs and generic drugs (in addition to innovative drugs) through the development of novel, technology-driven production processes. The United States must fundamentally address the vulnerability of its dependence on foreign nations for certain biopharmaceutical inputs and products through innovation, not tariffs.

For instance, as Drew Endy, a bioengineering professor at Stanford University, explains, novel bio-based manufacturing processes and new bio-fermentation techniques now “make possible the biosynthesis of active pharmaceutical ingredients through bio-brewing-based processes … we can actually leverage yeast to create a set of medicinal alkaloids,” including for many key APIs, a process which would exact far less of a toll on the environment as well.[58] As he continued, America could disrupt the currently dominant batch manufacturing processes used to make APIs with a less capital-intensive continuous-manufacturing process based on flow chemistry.[59] As another example, CONTINUUS Pharmaceuticals is working on an integrated continuous manufacturing solution that takes raw material, creates the desired API, purifies the API, and produces the final dosage form in a single system that can operate 24/7. A prototype reduced costs by 30–50 percent, solvent use by more than 60 percent, energy costs by 50–60 percent, facility footprint by about 90 percent, and lead time from months to less than 48 hours.[60]

To further articulate how the United States can reshore biopharmaceutical innovation through technological innovation, ITIF will host a May 7, 2025 event on “Making Medicines in America: How Congress Can Help America’s AI, Biopharma, and Manufacturing Industries Make It Happen.”[61]

Effective policy can address several challenges to making this vision a reality, however. First, it has historically been difficult for companies to secure FDA approval for new pharmaceutical and biomanufacturing processes. As W. Nicholson Price explained in a Boston College Law Review article, “Making Do in Making Drugs: Innovation Policy and Pharmaceutical Manufacturing,” companies seeking approval for a new drug are hesitant to put forward new manufacturing processes the FDA has not already approved in another context. Once manufacturing has begun, the FDA must certify any changes to a previously approved process. In part, as a result, the pharmaceutical industry has not seen the dramatic improvement in quality and efficiency that other industries have experienced.[62] Former CDER director Janet Woodcock recognized these challenges in recent Congressional testimony, observing that:

The adoption of advanced manufacturing technologies may pose a challenge to the current regulatory framework, because most regulations were developed based on traditional batch manufacturing methods under a unified pharmaceutical quality system. As a result, FDA has launched an effort to identify and implement needed changes in the regulatory structure.[63]

Indeed, one particular challenge is that the FDA still has not put forward a clear regulatory framework guiding the application of artificial intelligence (AI) applications in drug manufacturing processes.

The Trump administration is correct that society will need to bear a cost to bring certain advanced manufacturing activities back to the United States, whether with regard to semiconductors, pharmaceuticals, or other advanced manufacturing. But instead of asking society to bear the costs for greater drug production through tariffs, the Trump administration should ask society to bear it through very specific, targeted expenditures and incentives that will directly incent companies to make the desired investments in these industries. For instance, the aforementioned April 2025 National Security Commission on Emerging Biotechnology report determined that “the U.S. government should dedicate a minimum of $15 billion over the next five years to unleash more private capital into our national biotechnology sector.”[64] For drugs, such investments should pertain especially to targeted R&D programs designed to make U.S. biopharmaceutical drug, generic drug, and API manufacturing more cost competitive as well as tax credits.

To the former point, ITIF has called for policymakers to expand National Science Foundation (NSF) support to university-industry research centers working on biopharma production technology and potentially establish new centers.[65] In particular, policymakers should increase funding for NSF’s Division of Engineering and target much of the increase to the Chemical Process Systems Cluster and Engineering Biology and Health Cluster.[66] The administration should also encourage the creation of the biopharma equivalent of the Semiconductor Research Corporation, a public-private consortium that develops long-term semiconductor technology roadmap.[67] It would also be worth considering standing up another Manufacturing USA Institute alongside the National Institute for Innovation in Manufacturing Biopharmaceuticals (NIIMBL) that would focus on manufacturing innovations for APIs and generic drugs.

Targeted investment tax credits also represent far more powerful tools than tariffs to incentivize desired corporate behavior. ITIF has called for a supercharged advanced-industry tax credit that would allow traded-sector firms competing in certain advanced industries (including drugs) to take a 25 percent tax credit on all investments a machinery, buildings, and equipment.[68] This could be structured akin to the Alternative Simplified R&D Credit with a credit for all investment about 50 percent of annual average investments over the prior three to five years. The administration should also move to restore the Section 936 tax credit for biopharma production in Puerto Rico and other U.S. territories.[69]

(ix) the impact of current trade policies on domestic production of pharmaceuticals and pharmaceutical ingredients, and whether additional measures, including tariffs or quotas, are necessary to protect national security

U.S. biopharma companies are globally integrated and highly dependent on foreign markets, a factor highly abetted by existing U.S. trade policies, such as the WTO Pharmaceutical Agreement, through which the United States banded together with the EU and its 27 members along with Canada, Japan, Norway, and Switzerland to commit participants to reciprocal tariff elimination for pharmaceutical products and for chemical intermediates used in the production of pharmaceuticals.[70]

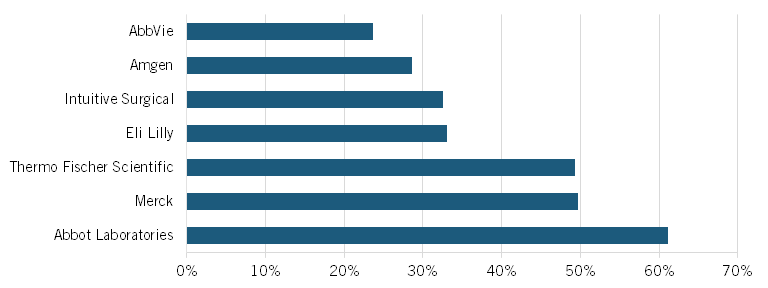

According to the National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics (NCSES) 2023 Annual Business Survey, non-U.S. operations among large pharmaceutical and medicine companies amounted to $220 billion, which represented 48 percent of the total revenues for businesses operating in the United States in this sector.[71] It is possible to observe a similar pattern by analyzing some of the top biopharmaceutical companies. Figure 2 shows foreign revenue as a percentage of global sales for seven of the largest U.S.-headquartered biopharmaceutical firms, all among the top 100 companies globally in terms of market size. On average, 40 percent of their sales, or $118 billion, originate in non-U.S. markets, ranging from 24 percent (AbbVie) to 61 percent (Abbott Laboratories).[72]

Figure 2: Non-U.S. share of select U.S. pharmaceutical companies’ revenues (2024)[73]

Expanding trade barriers, such as introducing tariffs or quotas, would incentivize globally integrated pharmaceutical companies to maintain a division between the American and non-U.S. markets. Trade barriers create an incentive to focus on the local market through local production. However, trade retaliation from third countries and the uncertainty surrounding lengthy trade negotiations create a counterbalancing incentive to serve non-U.S. markets with production from abroad. If a tariff is imposed, biopharmaceutical companies producing in the United States would likely face retaliatory tariffs if they wish to serve foreign markets with U.S. operations. Furthermore, tariffs on non-biopharmaceutical products that are part of the sector’s supply chain, such as intermediate goods, create additional incentives to keep a division between U.S. and non-U.S. markets.

(x) any other relevant factors

The Trump administration has suggested that it’s considering blanket 25 percent pharmaceutical tariffs.[74] This is not the most efficient way to retaliate against trade irritants or to incentivize the reshoring of pharmaceutical manufacturing. Despite all trade imbalances the U.S. pharmaceutical industry faces—which the Trump administration is correct to address—the United States retains a leadership position in this sector. Any intervention to correct these trade imbalances should not be at the detriment of America’s leadership.

In addition, such tariffs will considerably increase the price Americans pay for medicines. A new Ernst & Young study finds that a 25 percent U.S. tariff on pharmaceutical imports would increase U.S. drug costs by nearly $51 billion annually.[75] It should also be noted that the U.S. federal government is the largest purchaser of drugs, through federal agencies such as the Veterans Administration and the Department of Defense and federal programs such as Medicare Part B and D. For instance, the federal government spent $114 billion on Medicare Part B drugs alone in 2024 (part of the overall $1.9 trillion the federal government spent on health care programs and services that year).[76] Adding tariffs to imported pharmaceuticals would only raise the prices the U.S. government pays for drugs, counteracting other Trump administration efforts to reduce federal spending. (That said, an argument could be made that the incoming tariffs would offset the increased drug prices, so from an accounting basis it would a wash from the government’s perspective.)

Such tariffs would also increase U.S. biopharmaceutical industry production costs. In 2023, the U.S. pharmaceutical industry imported just over $60 billion of pharmaceutical products for further processing in domestic production facilities. Tariffs on these inputs alone could increase U.S. pharmaceutical production costs by $15.1 billion, reducing America’s competitiveness as a location to produce drugs for export.

Further to this point, the administration should also be mindful that, even if it does not apply pharmaceutical-specific tariffs, 10 percent global blanket tariffs will have a detrimental impact on America’s life-sciences innovation system. Biopharmaceutical R&D depends on a wide variety of specialized tools—such as gene sequencers or scanning tunneling electron microscopes—that hail from all corners of the world, just as biopharmaceutical manufacturing depends on a wide variety of specialized components—chemicals, bioreactors, filtration components, stainless steel vats, etc.—produced by a wide variety of specialized, best-of-breed global suppliers. Moreover, the cost tag of fabricating new biopharmaceutical plants is also likely to increase with the 25 percent tariffs the Trump administration has announced on steel. Ultimately, raising tariffs on these inputs will raise the cost of U.S. biopharmaceutical R&D and manufacturing, making U.S. drug production less cost efficient and U.S. drug exports less competitive, all while raising prices of drugs for American citizens.

The Trump administration is absolutely correct that the United States needs to identify and rectify critical foreign dependencies of key APIs and drugs. It is absolutely correct that the United States can and should manufacture more of the medicines it consumes domestically. It is correct that China represents a distinct and unique threat to America’s economy and security and that it deploys a brand of overt innovation mercantilism that threatens virtually all U.S. advanced-technology industries.[77] China’s vast panoply of mercantilist trade practices certainly merits a targeted U.S. response in the biopharmaceutical sector as well as others, which could range from tariffs to denying market access to Chinese products—and even enterprises entirely—when they look to sell products in U.S. (and allied) markets that benefit from pilfered IP, excessive subsidization leading to overcapacity, or other such mercantilist practices.[78]

But America’s foremost response to pharmaceutical trade imbalances with partner nations and inadequate domestic manufacturing of medicines should not be blanket tariffs. Rather, it should first focus on prevailing upon other nations to pay their fair share for innovative medicines. It should then focus on supporting public-private investments in novel technologies that will help make U.S. competitors both more innovative and cost-competitive, especially in the production of specific APIs or generic drugs that are now largely produced offshore. In this regard, the administration is to be commended for its commitment to reducing regulatory barriers to domestic pharmaceutical manufacturing.[79]

Several companies have recently announced significant U.S. investments in the sector. Johnson & Johnson announced in March 2025 it would increase U.S. investments by $55 million over the next four years.[80] Eli Lilly has committed to $27 billion in investments for four new U.S. manufacturing facilities.[81] And Merck announced in March it would build a $1 billion plant to manufacture vaccines in North Carolina.[82] These investments show the potential. However, as Eli Lilly CEO Dave Ricks noted on May 1, 2025, “We support the U.S. government’s goals to increase domestic investment.” Yet as he continued, “However, we don’t believe tariffs are the right mechanism. Rather, “enhanced” tax incentives—or an extension of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act—are “better tools” to spur U.S. growth.”[83] Indeed, the United States should level the playing field by working to effectively remediate other nations’ unfair practices (e.g., European drug price controls, China’s IP theft, etc.) but then turn its attention to ensuring that the United States offers the world’s best environment—in terms of R&D, tax, trade, and regulatory policy, workforce skills, robust IP rights, etc.—supporting life-sciences innovation.[84]

Thank you for your consideration.

Endnotes

[1] Notice of Request for Public Comments on Section 232 National Security Investigation of Imports of Pharmaceuticals and Pharmaceutical Ingredients, Docket No. 250414-0065, April 16, 2025, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2025/04/16/2025-06587/notice-of-request-for-public-comments-on-section-232-national-security-investigation-of-imports-of.

[2] “U.S. Pharmaceutical Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report by Molecule, By Product (Biologics & Biosimilars, Conventional Drugs), By Type, By Route of Administration, By Disease, By Age Group, By Distribution Channel, And Segment Forecasts, 2025 – 2030,” Grand View Research, accessed May 1, 2025, https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/us-pharmaceuticals-market-report.

[3] Robert D. Atkinson and Ian Tufts, “The Hamilton Index, 2023: China is Running Away with Strategic Industries” (ITIF, December 2023), https://itif.org/publications/2023/12/13/2023-hamilton-index/.

[4] Sandra Barbosu, “Not Again: Why the United States Can’t Afford to Lose Its Biopharma Industry,” (ITIF, February 2025), https://www2.itif.org/2024-losing-biopharma-leadership.pdf.

[5] Vadim J. Gurvich and Ajaz S. Hussain, “In and beyond COVID-19: US academic pharmaceutical science and engineering community must engage to meet critical National Needs” AAPS PharmSciTech Vol. 21, No. 5 (2020): 153; Fernando J. Muzzio et al., “Overcoming Global Risk to the Pharmaceutical Supply Chain for the United States: Achieving Pharmaceutical Independence by Reshoring Manufacturing Capacity and Capability,” (NIPTE, June 2024), https://nipte.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Overcoming-Global-Risk-to-the-Pharmaceutical-Supply-Chain_061824.pdf.

[6] “Generic Drugs,” U.S. Food & Drug Administration, accessed May 1, 2025, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/buying-using-medicine-safely/generic-drugs; Kimberlee Trzeciak, “Reflections on the 19th International Conference of Drug Regulatory Authorities,” December 2, 2024, https://www.fda.gov/international-programs/global-perspective/reflections-19th-international-conference-drug-regulatory-authorities?

[7] “Safeguarding Pharmaceutical Supply Chains in a Global Economy (Congressional Testimony of Janet Woodcock), October 2019, https://www.fda.gov/news-events/congressional-testimony/safeguarding-pharmaceutical-supply-chains-global-economy-10302019.

[8] “Global manufacturing capacity for active pharmaceutical ingredients remains concentrated,” US Pharmacopeia, November 2024, accessed May 1, 2025, https://qualitymatters.usp.org/global-manufacturing-capacity-active-pharmaceutical-ingredients-remains-concentrated.

[9] “Drug Shortages: Root Causes and Potential Solutions,” FDA, October 2019, https://www.fda.gov/media/131130/download; “Reliance on Foreign Sourcing in the Healthcare and Public Health Sector: Pharmaceuticals, Medical Devices, and Surgical Equipment,” December 2011, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/344365295_Reliance_on_Foreign_Sourcing_in_the_Healthcare_and_Public_Health_HPH_Sector_Pharmaceuticals_Medical_Devices_and_Surgical_Equipment.

[10] Woodcock, “Safeguarding Pharmaceutical Supply Chains in a Global Economy.”

[11] Ibid.; Barbosu, “Not Again: Why the United States Can’t Afford to Lose Its Biopharma Industry.”

[12] Woodcock, “Safeguarding Pharmaceutical Supply Chains in a Global Economy.”

[13] The (Biden) White House, “Fact Sheet: The United States Announced New Investments and Resources to Advance President Biden’s National Biotechnology and Biomanufacturing Initiative,” September 14, 2022, https://bidenwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/09/14/fact-sheet-the-united-states-announces-new-investments-and-resources-to-advance-president-bidens-national-biotechnology-and-biomanufacturing-initiative/.

[14] The (Biden) White House, “Fact Sheet: President Biden Announces New Actions to Strengthen American’s Supply Chains, Lower Costs for Families, and Secure Key Sectors,” November 27, 2023, https://bidenwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2023/11/27/fact-sheet-president-biden-announces-new-actions-to-strengthen-americas-supply-chains-lower-costs-for-families-and-secure-key-sectors/.

[15] “ASHP reports record high number of drug shortages,” American Hospital Association, April 12, 2024, https://www.aha.org/news/headline/2024-04-12-ashp-reports-record-high-number-drug-shortages; “AHA Comments before House Committee on Ways and Means on “Examining Chronic Drug Shortages in the United States,” February 6, 2024, https://www.aha.org/testimony/2024-02-06-aha-comments-house-committee-ways-and-means-examining-chronic-drug-shortages-united-states.

[16] Robert D. Atkinson, “China Is Rapidly Becoming a Leading Innovator in Advanced Industries” (ITIF, September 2014), https://itif.org/publications/2024/09/16/china-is-rapidly-becoming-a-leading-innovator-in-advanced-industries/.

[17] National Science Foundation, “Science & Engineering Indicators, Production and Trade of Knowledge- and Technology-Intensive Industries, Table SKTI-9: Value added of pharmaceuticals industry, by region, country, or economy: 2002–19;” accessed May 5, 2024, https://ncses.nsf.gov/pubs/nsb20226/data.

[18] Yi Wu, “China’s Biopharma Industry: Market Prospects, Investment Paths,” China Briefing, November 10, 2022, https://www.china-briefing.com/news/china-booming-biopharmaceuticals-market-innovation-investment-opportunities/.

[19] “China Government Initiatives in Biotechnology,” Global X by Mirae Asset, February 2020, https://www.globalxetfs.com.hk/content/files/China_Government_Initiatives_in_Biotechnology.pdf.

[20] “Outline of the People’s Republic of China 14th Five-Year Plan for National Economic and Social Development and Long-Range Objectives for 2035,” Translation, Center for Security and Emerging Technology (CSET), https://cset.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/t0284_14th_Five_Year_Plan_EN.pdf.

[21] Han Yu, “2022 Annua Report,” National Natural Science Foundation of China, https://www.nsfc.gov.cn/english/site_1/pdf/NSFC%20Annual%20Report%202022.pdf; “China’s science foundation ups research budget to 33b yuan,” The State Council The People’s Republic of China, accessed July 8, 2024, https://english.www.gov.cn/news/topnews/202203/25/content_WS623d8d30c6d02e5335328459.html.

[22] Robert D. Atkinson, “The Impact of China’s Policies on Global Biopharmaceutical Industry Innovation” (ITIF, September 2020), https://itif.org/publications/2020/09/08/impact-chinas-policies-global-biopharmaceutical-industry-innovation/; Lawrence Tabak and Roy Wilson, “Foreign Influences on Research Integrity” (presented at the 117th meeting of the advisory committee to the director, NIH, December 13, 2005), https://acd.od.nih.gov/documents/presentations/12132018ForeignInfluences.pdf.

[23] Alex Keown, “Harvard Professor Arrested as Government Continues to Crack Down on Researchers’ Financial Ties to China,” BioSpace, January 29, 2020, https://www.biospace.com/article/harvard-professor-two-chinese-national-charged-with-lying-about-ties-to-government-of-china/.

[24] Kenneth Rapoza, “To Build China’s Biotech, Just Keep Stealing: DoJ Jails Two For Spying,” Coalition for a Prosperous America, April 23, 2021, accessed July 15, 2024, https://prosperousamerica.org/china-ip-theft-in-ohio/.

[25] Office of the United States Trade Representative Executive Office of the President, Update Concerning China’s Acts, Policies, and Practices Related to Technology Transfer, Intellectual Property, and Innovation (Washington, D.C.: USTR, November 2018), 11, https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/enforcement/301Investigations/301%20Report%20Update.pdf.

[26] Jeremy Roebuck, “Chinese American scientist admits plot to steal GlaxoSmithKline’s secrets for firm in China,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, August 31, 2018, http://www.philly.com/philly/news/pennsylvania/philadelphia/chinese-american-scientist-admits-plot-to-steal-glaxosmithklines-trade-secrets-for-firm-in-china-20180831.html.

[27] Zeba Siddiqui, “Five Eyes intelligence chiefs warn on China’s ‘theft’ of intellectual property,” Reuters, October 18, 2023, accessed July 10, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/five-eyes-intelligence-chiefs-warn-chinas-theft-intellectual-property-2023-10-18/.

[28] National Security Commission on Emerging Biotechnology (NSCEB), “Charting the Future of Biotechnology,” (NSCEB, April 25), 28, https://www.biotech.senate.gov/final-report/chapters/.

[29] Robert D. Atkinson, “China’s Biopharmaceutical Strategy: Challenge or Complement to U.S. Industry Competitiveness?” (ITIF, August 2019), https://itif.org/publications/2019/08/12/chinas-biopharmaceutical-strategy-challenge-or-complement-us-industry/.

[30] International Trade Administration, “2016 Top Markets Report Pharmaceuticals Country Case Study,” 3, https://www.trade.gov/topmarkets/pdf/Pharmaceuticals_China.pdf.

[31] Biotechnology Industry Association (BIO), “2019 USTR 301 Filing” (BIO, 2019), 25.

[32] Angus Liu, “Riding on Booming Drug Sales, Astra Zeneca Forms $133M China Joint Venture,” FierceBiotech, November 27, 2017, https://www.fiercebiotech.com/biotech/riding-booming-drug-sales-astrazeneca-forms-133m-china-joint-venture; Stephan Booshart, Thomas Luedi, and Emma Wang, “Past lessons for China’s new joint ventures,” (McKinsey & Company, 2010), https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/past-lessons-for-chinas-new-joint-ventures.

[33] Am Cham Shanghai and LEK Consulting, “Innovation in China, ‘Made in China 2025,’ and Implications for Healthcare MNCs,” GPS Healthcare Quarterly, July 2018, https://www.lek.com/sites/default/files/insights/pdf-attachments/Chinas-Healthcare-Innovation-by-Made-in-China-2025-and-Implications-for-MNCs_JUL06.pdf.

[34] Trevor Hoey, “Genetic Technologies benefits from Healthy China Policy,” finfeed, March 28, 2091, https://finfeed.com/small-caps/biotech/genetic-technologies-benefits-healthy-china-policy/.

[35] Tom Miles, “U.S. Sends 70 Questions to WTO About China’s Subsidies,” Reuters, January 30, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-trade-china-subsidies/u-s-sends-70-questions-to-wto-about-chinas-subsidies-idUSKCN1PO1HN.

[36] Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS), “Lab Leader, Market Ascender: China’s Rise in Biotechnology,” (MERICS, April 2025), https://merics.org/sites/default/files/2025-04/MERICS%20Report%20Biotech_04-2025.pdf.

[37] Testimony before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission Hearing On: “China’s Pursuit of Next Frontier Tech: Computing, Robotics, and Biotechnology,” 115th Cong. (2017), (testimony of Benjamin A. Shobert, Founder and Managing Director, Rubicon Strategy Group Senior Associate, National Bureau of Asian Research).

[38] Government Accountability Office (GAO), “Drug Safety: FDA Has Improved Its Foreign Drug Inspection Program, but Needs to Assess the Effectiveness and Staffing of Its Foreign Offices,” (GAO, 2016), https://www.gao.gov/assets/690/681689.pdf.

[39] Trelysa Long and Stephen Ezell, “The Hidden Toll of Drug Price Controls: Fewer New Treatments and Higher Medical Costs for the World” (ITIF, July 2023), https://itif.org/publications/2023/07/17/hidden-toll-of-drug-price-controls-fewer-new-treatments-higher-medical-costs-for-world/.

[40] U.S. Health and Human Services, “International Prescription Drug Price Comparisons” (Appendix C: Table C.1. Calculated US Versus Other-Country Price Indices, 2018), https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/ca08ebf0d93dbc0faf270f35bbecf28b/international-prescription-drug-price-comparisons.pdf.

[41] Ibid.; The World Bank, “GDP per capita, PPP (current international $), GDP per capita, PPP for 33 countries),” accessed May 23, 2023, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD.

[42] U.S. Health and Human Services, “International Prescription Drug Price Comparisons” (Appendix C: Table C.1. Calculated US Versus Other-Country Price Indices, 2018; The World Bank, GDP per capita, PPP.

[43] Sandra Barbosu, “America Funds Cures—The World Must Share the Burden,” Innovation Files, April 21, 2025, https://itif.org/publications/2025/04/21/america-funds-cures-the-world-must-share-the-burden/.

[44] Pharmaceutical Spreadsheet: United States Census Bureau, USA Trade (imports and exports for pharmaceutical products (HS30), accessed April 30, 2025), https://usatrade.census.gov/.; World Bank, World Development Indicators (GDP (current $), accessed April 30, 2025), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators. (Note: The countries selected here represent the world’s top 25 largest economies, and then the 10 countries with which the United States runs the largest pharmaceutical trade deficits and 10 largest surpluses.)

[45] United States Trade Representative’s Office (USTR), “2025 Special 301 Report,” (USTR, 2025), 54, https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/files/Issue_Areas/Enforcement/2025%20Special%20301%20Report%20(final).pdf.

[46] Berengere Macabeo et al., “Access to innovative drugs and the National Reimbursement Drug List in China: Changing dynamics and future trends in pricing and reimbursement” Journal of Market Access and Health Policy, vol. 11, no. 1 (2023): https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10266112/.

[47] Atkinson, “The Impact of China’s Policies on Global Biopharmaceutical Industry Innovation.”

[48] Sandra Barbosu, “How Innovative Is China in Biotechnology” (ITIF, July 2024), https://itif.org/publications/2024/07/30/how-innovative-is-china-in-biotechnology/.

[49] Chia-Feng Lu and Dawn (Dan) Zhang, “China on the move: Lesson from China’s National negotiation of drug prices in 2022,” (GT Greenberg Traurig, February 27, 2023), accessed May 5, 2024, https://www.gtlaw.com/en/insights/2023/2/china-on-the-move-lesson-from-chinas-national-negotiation-of-drug-prices-in-2022.

[50] Atkinson, “The Impact of China’s Policies on Global Biopharmaceutical Industry Innovation.”

[51] James Strachan, “Make China Great Again,” The Medicine Maker, July 2018, https://themedicinemaker.com/fileadmin/user_upload/TMM_0718.pdf.

[52] Atkinson, “China’s Biopharmaceutical Strategy: Challenge or Complement to U.S. Industry Competitiveness?”

[53] Milton Ezrati, “How Much Control Does China Have Over Rare Earth Elements?” Forbes, December 11, 2023, https://www.forbes.com/sites/miltonezrati/2023/12/11/how-much-control-does-china-have-over-rare-earth-elements/.

[54] NSCEB, “Charting the Future of Biotechnology,” 17.

[55] Rebecca Robbins, “Trump’s Next Tariffs Could Target Foreign-Made Medicines,” The New York Times, April 4, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/04/04/health/drug-tariffs-trump-manufacturing.html.

[56] NSCEB, “Charting the Future of Biotechnology,” 29.

[57] Avalere Health, “Majority of API in US-Consumed Medicines Is Produced in the US,” January 31, 2022, https://advisory.avalerehealth.com/insights/majority-of-api-in-us-consumed-medicines-is-produced-in-the-us-2020.

[58] Stephen Ezell phone interview with Drew Endy, professor of Bioengineering at Stanford University and president of the BioBricks Foundation.

[59] Stephen Ezell, “Faulty Prescription: Why a “Buy American” Approach for Drugs and Medical Products Is the Wrong Solution” (ITIF, June 2020), https://itif.org/publications/2020/06/15/faulty-prescription-why-buy-american-approach-drugs-and-medical-products/.

[60] National Academies Press (NAP), “Innovations in Pharmaceutical Manufacturing: Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief,” (NAP, 2020), 3, https://wwwnap.edu/catalog/25814/innovations-in-pharmaceutical-manufacturing-proceedings-of-a-workshop-in-brief.

[61] ITIF, “Making Medicines in America: How Congress Can Help America’s AI, Biopharma, and Manufacturing Industries Make It Happen,” https://itif.org/events/2025/05/07/making-medicines-in-america-2025/.

[62] W. Nicholson Price II, “Making Do in Making Drugs: Innovation Policy and Pharmaceutical Manufacturing” Boston College Law Review, Vol. 55, Issue 2 (2014): 492, https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr/vol55/iss2/5/.

[63] “Safeguarding Pharmaceutical Supply Chains in a Global Economy,” Before the U.S. House Committee on Energy and Commerce, Subcommittee on Health, 116th Cong. (October 30, 2019) (statement of Janet Woodcock, Director of FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research), https://www.fda.gov/news-events/congressional-testimony/safeguarding-pharmaceutical-supply-chains-global-economy-10302019.

[64] NSCEB, “Charting the Future of Biotechnology,” 10.

[65] Stephen Ezell, “Ensuring U.S. Biopharmaceutical Competitiveness” (ITIF, July 2020), https://itif.org/publications/2020/07/16/ensuring-us-biopharmaceutical-competitiveness/.

[66] National Science Foundation, “Programs: Directorate for Engineering (ENG),” https://www.nsf.gov/funding/programs.jsp?org=ENG.

[67] Semiconductor Research Corporation, “Decadal Plan for Semiconductors,” https://www.src.org/about/decadal-plan.

[68] Robert D. Atkinson et al., “A Techno-Economic Agenda for the Next Administration” (ITIF, June 2024), https://itif.org/publications/2024/06/10/a-techno-economic-agenda-for-the-next-administration/.

[69] Ezell, “Ensuring U.S. Biopharmaceutical Competitiveness,” 53.

[70] Office of the United States Trade Representative, “Pharmaceuticals,” https://ustr.gov/issue-areas/industry-manufacturing/industry-initiatives/pharmaceuticals.

[71] National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics (NCSES), “Annual Business Survey: 2023,” https://ncses.nsf.gov/surveys/annual-business-survey/2023.

[72] Based on the Securities and Exchange Commission’s Form 10-K reported by Abbott Laboratories, AbbVie, Amgen, Eli Lilly, Intuitive Surgical, Merck, and Thermo Fischer Scientific for 2024. (Author’s analysis.)

[73] Author’s analysis of these companies’ most recent 10K reports (analysis conducted the week of April 28, 2025).

[74] Robbins, “Trump’s Next Tariffs Could Target Foreign-Made Medicines.”

[75] Maggie Fick, “Exclusive: US pharma tariffs would raise US drug costs by $51 billion annually, report finds,” Reuters, https://www.reuters.com/business/healthcare-pharmaceuticals/us-pharma-tariffs-would-raise-us-drug-costs-by-51-bln-annually-report-finds-2025-04-25/.

[76] Juliette Cubanski, Alice Burns, and Cynthia Cox, “What Does the Federal Government Spend on Health Care?” Kaiser Family Foundation, February 24, 2025, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/what-does-the-federal-government-spend-on-health-care/.

[77] Robert D. Atkinson, “Industry by Industry: More Chinese Mercantilism, Less Global Innovation” (ITIF, May 2021), https://itif.org/publications/2021/05/10/industry-industry-more-chinese-mercantilism-less-global-innovation/.

[78] Robert D. Atkinson, “How to Mitigate the Damage From China’s Unfair Trade Practices by Giving USITC Power to Make Them Less Profitable” (ITIF, November 2022), https://itif.org/publications/2022/11/21/how-to-mitigate-the-damage-from-chinas-unfair-trade-practices/.

[79] The Trump White House, “Fact Sheet: President Donald J. Trump Announces Actions to Reduce Regulatory Barriers to Domestic Pharmaceutical Manufacturing,” news release, May 5, 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/fact-sheets/2025/05/fact-sheet-president-donald-j-trump-announces-actions-to-reduce-regulatory-barriers-to-domestic-pharmaceutical-manufacturing/.

[80] Bhanvi Satija and Patrick Wingrove, “J&J boosts US investments by 25% over 4 years amid looming tariff threats,” Reuters, March 21, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/business/jj-plans-invest-more-than-55-billion-us-over-next-four-years-2025-03-21/.

[81] Daniel Lee, “Eli Lilly to spend $27 billion on four new manufacturing sites and create 3,000 jobs,” Indiana Economic Digest, March 5, 2025, https://indianaeconomicdigest.net/MobileContent/Most-Recent/Company-News/Article/Eli-Lilly-to-spend-27-billionon-four-new-manufacturing-sites-and-create-3-000-jobs/31/64/118577.

[82] Merck, “Merck Unveils New Facility to Increase Vaccine Production Capacity,” news release, March 11, 2025, https://www.merck.com/news/merck-unveils-new-facility-to-increase-vaccine-production-capacity/.

[83] Fraiser Kansteiner, “Lilly CEO urges Trump admin to 'level the playing field' by negotiating trade deals, striking down tariffs,” Fierce Pharma, May 1, 2025, https://www.fiercepharma.com/pharma/lilly-ceo-urges-trump-administration-level-playing-field-negotiating-trade-deals-striking.

[84] Ezell, “Ensuring U.S. Biopharmaceutical Competitiveness.”