A Blueprint for Broadband Affordability

Congress should create a more targeted and durable Affordable Connectivity Program by aligning funding priorities with the remaining causes of the digital divide. By prioritizing affordability rather than deployment, the new program can connect low-income households without new federal spending.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Key Takeaways

Contents

Lack of Broadband Adoption Is the Leading Cause of the Digital Divide. 2

Looking Back at the Affordable Connectivity Program. 4

A Blueprint for Broadband Affordability 6

Introduction

Private and federal broadband investments have achieved universal broadband deployment throughout the United States. Still, barriers that prevent some households from accessing the Internet remain. This lack of broadband adoption, not lack of deployment, is the central reason for the remaining digital divide. Therefore, identifying and addressing barriers to broadband adoption should be the core of broadband policy.

One major barrier to broadband adoption is whether low-income households can afford it. ACP was a step in the right direction to effectively address the affordability problem, but it was overly broad and ran out of money last summer and has not been replaced. Meanwhile, deployment programs continue to get billions of dollars year after year. By reversing these priorities to put more focus on affordability, rather than deployment subsidies, we can address a real remaining cause of the digital divide without new federal spending.

Lack of Broadband Adoption Is the Leading Cause of the Digital Divide

To date, most federal broadband policy has focused on broadband deployment: building the infrastructure to remote areas of the country so that everyone could have the possibility of accessing the Internet. Today, the overwhelming majority of locations in the United States have access to broadband infrastructure. The deployment problem has been solved.

According to the Federal Communications Commission’s (FCC’s) National Broadband Map, as of June 2024, 94 percent of locations in the United States had access to terrestrial broadband service with speeds of at least 100 Megabits per second (Mbps) download and 20 Mbps upload.[1] But deployment progress has become all but complete in recent months as low-earth orbit (LEO) satellite service has become available throughout the United States. The FCC reports that 99.98 percent of U.S. locations now have access to 100/20 Mbps broadband.[2]

Before the wide deployment of LEO constellations, very remote areas would have had to wait a long time or pay tens of thousands of dollars to get high-speed broadband infrastructure through the rugged or rural terrain to individual households. With satellites, however, the infrastructure now hovers overhead, providing speeds and prices comparable to terrestrial technologies. Given these technological developments and already allocated federal funds, universal broadband deployment should be considered a reality for the purposes of policy planning.

The digital divide persists, however, because many people to whom broadband is available do not subscribe to it. According to the most recent data from the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA), the majority of people who do not use the Internet at home say the reason is that they “don’t need” it or are “not interested.”[3] This group should be an important priority for broadband policy, but it is also somewhat ill defined and in need of more study before scalable policy solutions will be successful.[4]

Universal broadband deployment should be considered a reality for the purposes of policy planning.

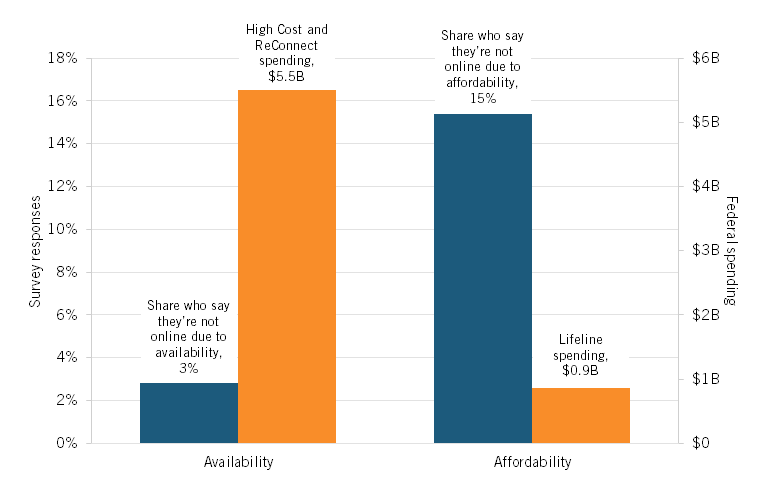

The second-place reason for non-use of the Internet at home, however, is affordability, cited by 15.4 percent of respondents.[5] This substantial chunk of the digital divide is tractable and can be addressed by a targeted affordability program.

Yet, broadband policy remains stuck in deployment mode. The U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) found that among the dozens of fragmented and overlapping federal broadband programs, no less than six are focused exclusively on deployment.[6] The largest such programs, the FCC’s High-Cost program and the Department of Agriculture’s ReConnect Fund, together average $5.5 billion annually.[7] In addition, Congress has allocated an extra $42.45 billion primarily for broadband deployment through the Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment (BEAD) Program.[8]

It’s past time for federal broadband policy to shift to addressing barriers to broadband adoption beyond deployment. Broadband affordability is a solvable problem if policymakers are willing to prioritize it over wasteful deployment spending.

Figure 1: Consumers’ needs versus the balance of federal spending on broadband availability and affordability

Affordability Defined

Whether broadband is affordable is a distinct question from whether it is cheap. The same broadband price might be easily within the means of some households but unaffordable for others. Therefore, the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), the FCC, and the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) have previously used 2 percent of a household’s income as a benchmark for affordability.[9] This definition captures the fact that affordability is always relative to the household paying for broadband, rather than being simply an attribute of Internet service providers’ (ISPs’) offerings.

In the United States, for example, broadband prices exhibit market competition and are, on average, well within the 2 percent benchmark for high-quality service.[10] But since many households have below-average income, even a competitive price is above the affordability benchmark for some people. That is the affordability problem.

Notably, this problem would not be solved by rate regulation. No matter what the regulated rate, there will always be some low-income households for which it is unaffordable. Therefore, rate regulation would fail to address the affordability problem while also subsidizing service for people who can afford market prices.

Instead, the solution to broadband affordability is to give direct financial assistance to low-income consumers to help them afford to buy market-price broadband. This is the same principle we use for necessities such as housing and food.[11] For broadband, this solution should follow the model set by the erstwhile ACP.

Since many households have below-average income, even a competitive price is above the affordability benchmark for some people. That is the affordability problem.

Looking Back at the Affordable Connectivity Program

ACP began its life at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic as the Emergency Broadband Benefit.[12] It morphed into ACP as part of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, which allocated a lump sum of $14.2 billion for it. The FCC administered the program, officially launching it on New Year’s Eve 2021.[13]

The program itself provided up to $30 per month to eligible households, which they could choose to spend on fixed or mobile broadband service.[14] It also included a $100 discount for an Internet-connected device.[15]

There were several ways to qualify for old ACP. Primarily, it was open to any household with an income at or below 200 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL).[16] Other ways to qualify included participation in another low-income assistance program, receipt of a Pell Grant, or qualification for a private ISP’s existing low-income program.[17]

The program eventually enrolled 23 million households, but the $14.2 billion pot of money quickly dwindled.[18] Efforts to persuade Congress to renew funding for ACP failed, and the program officially ended in June of 2024 as all funds were exhausted.[19]

While there was bipartisan support for ACP, including strong support from now Vice President JD Vance, several objections effectively removed any chance of that coalition becoming sufficiently broad to make ACP a policy priority.[20] Dealing with each will be necessary to make a new affordability plan sustainable.

Was ACP Eligibility Too Broad?

The main way to qualify for ACP was by having a household income below 200 percent of the FPL. The broad eligibility criteria swept in around 42 percent of U.S. households. For a four-person household, the 200 percent of FPL amounted to an annual income of $62,400.[21] Using the 2 percent affordability benchmark, that household would be expected to be able to afford a $104 per month broadband subscription. Since ACP subscriptions were generally priced at $30 (such that ACP made the consumer’s marginal cost zero), there is good reason to think that such eligibility criteria were overinclusive.[22] Indeed, most wireline ACP subscribers still have their connection today, even though they no longer get the ACP benefit.[23] This fact could be due to private ISPs picking up the slack and offering their own low-income plans, but these necessarily provide a smaller benefit than ACP did.

This wide net perhaps made sense during ACP’s origin as a COVID-era emergency program given the extreme impacts on all households, but that level of eligibility cannot be made permanent while maintaining the program long term. The overinclusivity of ACP caused it to run out of money faster than it otherwise would have and provided grist for the mill of fiscally conservative objections that contributed to ACP’s political intractability.

Should ACP Be Open Only to First-Time Subscribers?

While expending funds for broadband to those who could afford it is a problem for sustainable affordability policy, that does not mean that ACP was a failure any time it benefited someone who would have had a broadband connection anyway. Objections on these grounds make the category mistake of conflating affordability with choices made under a budget constraint.

Broadband affordability policy should not penalize households that recognize the value of broadband to lift them out of poverty and which, therefore, prioritize it at the expense of other necessities.

The point of broadband affordability policy is to make broadband affordable as defined by 2 percent of household income. Broadband is just one of the components of a basket of goods that are necessities for a household alongside food, housing, electricity, water, etc. For low-income households, compromising on some components of that basket is inevitable. Perhaps one buys less food to afford to pay rent while another goes without heat to keep the lights on. Money is fungible. The fact that a low-income household making these trade-offs may choose to pay for broadband and compromise on something else does not mean that broadband is affordable to it. Broadband affordability policy should not penalize households that recognize the value of broadband to lift them out of poverty and which, therefore, prioritize it at the expense of other necessities. Rather, affordability policy should make broadband affordable for qualifying households so that they can use more of their income for other necessities.

In short, the question is whether broadband would be affordable to a given household in the absence of ACP, not whether they would buy it. Whenever the first-time-subscriber objection is a reasonable one, it is really an issue of overbroad eligibility criteria. Therefore, as discussed ahead, the better solution is to tailor eligibility criteria to screen out those households for which broadband would have been genuinely affordable without it.

Does ACP Increase Broadband Prices for Nonrecipients?

A final objection to ACP suggests that it was pushing up prices for broadband across the board.[24] In the end, however, this objection again appears to be an issue of overbroad eligibility criteria rather than a fundamental problem with any version of ACP.

It is generally true that a market-wide subsidy will push up the price of a subsidized good: if everyone had an extra $100 to spend on a smartphone, that would cause an increase in demand for smartphones which would, in turn, allow sellers to make more profit at a higher price. But the key factor in that hypothetical is that everyone got the subsidy, so the whole market would buy more smartphones at the same price as before.

A properly tailored ACP is unlike that scenario, however, because the eligibility requirements ensure that the subsidies go only to a fraction of the marketplace. Specifically, they go to households which would otherwise buy less than one of the basket of goods deemed “necessities.” Even if it’s true that old ACP pushed up prices, that would be a symptom of overbroad eligibility, a problem that would be fixed by our proposal.

Another way of looking at ACP is as a form of price discrimination: just as restaurants can provide lower prices for senior citizens without raising prices for other consumers, ACP is a discount for low-income consumers that does nothing per se to harm nonrecipients. Price discrimination is often an effective, pro-consumer way to incorporate more consumers into a market while increasing the welfare of both buyers and sellers in that market.

A Blueprint for Broadband Affordability

A renewed, targeted voucher program, styled after ACP, should be the central broadband funding priority. Like ACP, the program should be flexible, allowing beneficiaries to spend it on whatever broadband service they want; it should cover any speed tier and either fixed or mobile connectivity regardless of the technology that delivers it. Here are the details of how it should work.

Eligibility

There should be two ways to qualify for this new voucher:

1. Having a household income at or below 135 percent of the FPL.

2. Being in the first three months of unemployment insurance.

A renewed, targeted voucher program, styled after ACP, should be the central broadband funding priority.

The 135 percent criterion, which would make around 1 in 4 U.S. households eligible, matches the main eligibility criterion for Lifeline, the program most parallel to ACP in the Universal Service Fund (USF). This fact would make applying for ACP simple and administrable. The program should also grandfather in current Lifeline recipients, and Lifeline should be eliminated since this new program replaces it with a larger, more flexible benefit.

Covering broadband costs for individuals who lose their job through no fault of their own is a win-win. Losing one’s job presents a sudden hit to a household’s income, but staying online is key to searching and applying for a new one. The government could save money by enabling connectivity to shorten periods of unemployment rather than paying out more unemployment benefits to connectivity-insecure households that would, for that reason, have a hard time finding a new job.[25] Thus, this eligibility criterion would likely save the government money and enable households to get back on their feet after a period of unemployment.

Benefit Amount

The amount of the New ACP benefit should be $30 per month per eligible household.

This number is based on what would make a $75/month broadband subscription fall within the 2 percent of income affordability benchmark for a two-person household at 135 percent of the FPL. This single benefit amount for all participants would both make the program easily administrable and lower bureaucratic burdens on participants.

This is a conservative estimate of the amount needed to meaningfully address the affordability problem because it considers a below-average household size and a subscription price well above what major providers offered during old ACP. Indeed, most providers offered a $30 plan such that the price to the consumer was zero. Therefore, there should be little worry that even much lower-income households would have access to affordable broadband with a $30 benefit. This fact provides breathing room within this proposal for some tinkering with the benefit amount to reduce the fiscal impact of the program if necessary. If ISPs are willing to offer a subscription with a $30 sticker price (as opposed to the hypothesized $75 used for this calculation), a smaller benefit amount would be just as successful in making broadband affordable. Many providers have continued low-income options even without ACP, and the federal government could partner with ISPs to supplement these. Or Congress could use this wiggle room to provide a larger benefit to households in areas that are served only by higher-priced options.[26] In short, there are many ways to tailor the details of this proposal to on-the-ground realities and political priorities.

Estimated Cost

To estimate the cost of New ACP, we used the fact that this benefit would mirror one of the major eligibility criteria for Lifeline (and would grandfather in those who qualify by other criteria). Approximately 33.2 million households are eligible for Lifeline.[27] This is an upper bound for New ACP since this plan eliminates some of the ways one could qualify for Lifeline. The annualized cost per household that participates in New ACP would be $360. About 28 percent of eligible households participated in old ACP.[28]

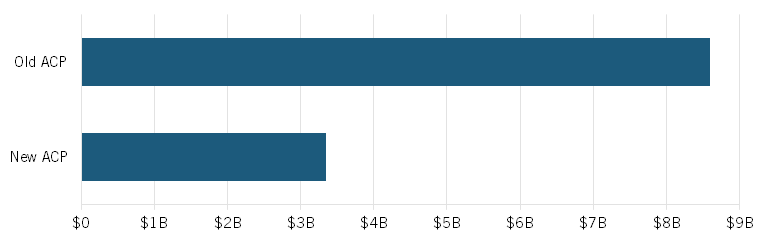

The estimated annual cost of New ACP is $3.4 billion per year. This is a significant decrease from the $8.6 billion annual price tag of old ACP.

Applying the annualized cost of New ACP to the number of Lifeline-eligible households participating at the same rate as ACP-eligible households in old ACP yields an estimated annual cost of New ACP of $3.4 billion per year (33.2 million * $360 * 0.28 = $3.35 billion). This is a significant decrease from the $8.6 billion annual price tag of old ACP, leaving it more financially sustainable and politically palatable. Moreover, when paired with other common sense broadband reforms, New ACP would not require any new funding.

Figure 2: Estimated costs of old and New ACP

Paying for the Plan

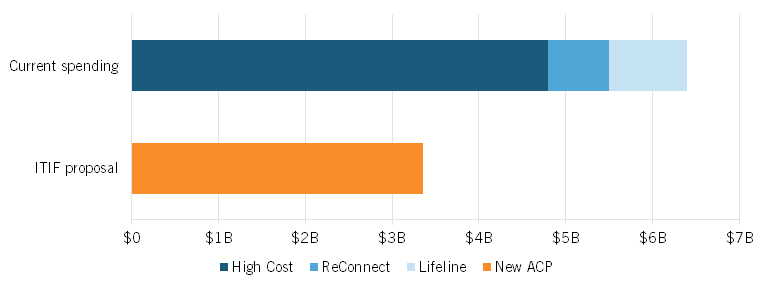

Today’s allocation of broadband funding, focusing on deployment rather than adoption, means that a change in priorities, not additional money, would be sufficient to fund New ACP.

Just prioritizing affordability over deployment would save over $6.3 billion. That’s more than enough to sustain New ACP.

Take just two of the largest broadband deployment programs, USF’s High Cost program and the Department of Agriculture’s ReConnect program. Over the last five years, High Cost has averaged $4.8 billion per year. The median spending for ReConnect during that period was just under $700 million. So just by eliminating programs that fund the already-solved problem of broadband deployment, we’d have an extra $5.5 billion to spend on adoption.

Furthermore, New ACP would replace the Lifeline program, so it’s annual average of $867 million could also be reallocated. In sum, just prioritizing affordability over deployment would save over $6.3 billion. That’s more than enough to sustain the estimated $3.4 billion cost of New ACP.

Table 1: Reimbursement spending on Lifeline, High-Cost USF, and USDA’s ReConnect program[29]

|

Year |

Lifeline |

High Cost |

ReConnect |

|

2018 |

$1,162,115,968 |

$4,835,867,545 |

|

|

2019 |

$982,002,823 |

$5,146,678,647 |

$442,179,093 |

|

2020 |

$853,660,100 |

$5,062,558,119 |

$694,033,081 |

|

2021 |

$723,769,573 |

$5,128,383,959 |

|

|

2022 |

$609,934,746 |

$4,165,548,744 |

$1,335,705,967 |

|

2023 |

$869,882,875 |

$4,328,366,462 |

$702,970,000 |

|

Average |

$866,894,348* |

$4,777,900,579* |

$698,501,541** |

*Mean. **Median.

Of course, the unorthodox funding mechanism of USF and the vagaries of congressional budgeting make simple reallocation of its funding more complicated. But Congress could first creatively craft legislation that transforms USF into a normal appropriation of collected funds and then simultaneously sunset Lifeline and High Cost while appropriating the savings to New ACP.

For both eligible participants and ISPs to have confidence in New ACP, Congress should appropriate funding for it on a long-term, multiyear basis. The longer-term appropriations would prevent political considerations from leaving the program on a knife’s edge such that consumers lose the benefits, temporarily or permanently, and thereby lose trust in the program even if it is eventually renewed. Likewise, ISPs will dedicate more resources to marketing and administering ACP-eligible plans if they believe the program is stable enough to keep those customers around.

Figure 3: ITIF proposal to shift funding from deployment to affordability while reducing overall spending

Since our proposal runs in tandem with USF reform, it is important to underline that ACP should not be funded by USF contributions. While there has been much discussion of how to lower the USF contribution factor and how to more fairly allocate its burden, none of those proposals broaden the contribution base as much as appropriations from general tax revenue. The base of all taxpayers is the broadest one there is. Moreover, contrary to some proposals, there is no free lunch to be had by simply raising taxes on unpopular industries in an effort to relieve the total burden on consumers. Just like other sales taxes, which party is legally required to transmit the money to the government is irrelevant to the real burden of the tax.[30] Just as consumers really pay the USF contributions that are legally levied on telecommunications providers, so consumers would ultimately shoulder the burden of USF fees on ISPs, cloud services, digital advertising, etc.[31] If there is a need to expand the USF contribution base, there is no broader base than all taxpayers, which is the source of appropriated funds.

For both eligible participants and ISPs to have confidence in New ACP, Congress should appropriate funding for it on a long-term, multiyear basis.

Furthermore, the imperative of USF reform is coming due at a time when the very structure of USF is in serious legal jeopardy. The Supreme Court has granted certiorari in a case that could find all or part of the off-the-books USF funding mechanisms unconstitutional.[32] Given the current court’s appetite for reining in unaccountable administrative agencies, Congress should not underrate the chance that the traditional USF funding mechanisms will soon be illegal. It would, therefore, be foolish to put an essential broadband program, including New ACP, into such a tenuous legal situation. Indeed, Congress will be hard pressed to preserve any USF program if it does not act soon to moot the case. Reforming USF to focus on New ACP funded by appropriations would accomplish just that.

Conclusion

This plan is a compromise. It is substantially smaller than old ACP, but it also is more likely to be sustainable and provide real help to households that need it most. As discussed, Congress should tinker with the eligibility criteria or the benefit amount as necessary to make the finances of New ACP sustainable and politically palatable. An active, long-term program that provides smaller benefits to fewer people is better than no benefits at all.

Closing the digital divide should remain a major priority for American broadband policy, but the causes of that divide have changed more quickly than our policies to address them have. The status quo has sacrificed effective solutions for broadband affordability yet continues to spend large sums on both broadband deployment and covering the operating expenses of unprofitable ISPs. Shifting broadband priorities from deployment to affordability will take a bigger chunk out of the digital divide than current policy will. The new Congress should adopt a renewed, narrowly tailored ACP and fund it with appropriations to provide a stable and effective affordability plan for households that need it to join the connected economy.

About the Author

Joe Kane is director of broadband and spectrum policy at ITIF. Previously, he was a technology policy fellow at the R Street Institute, where he covered spectrum policy, broadband deployment and regulation, competition, and consumer protection. Earlier, Kane was a graduate research fellow at the Mercatus Center, where he worked on Internet policy issues, telecom regulation, and the role of the FCC, where he interned in the office of Chairman Ajit Pai. He holds a J.D. from The Catholic University of America, a master’s in economics from George Mason University, and a bachelor’s in political science from Grove City College.

About ITIF

The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) is an independent 501(c)(3) nonprofit, nonpartisan research and educational institute that has been recognized repeatedly as the world’s leading think tank for science and technology policy. Its mission is to formulate, evaluate, and promote policy solutions that accelerate innovation and boost productivity to spur growth, opportunity, and progress. For more information, visit itif.org/about.

Errata

This report has been updated in the “Estimated Cost” section, and in figure 2 and figure 3, to correct the calculation of the total cost for ITIF’s proposed New ACP: We estimate the new program would cost $3.35 billion, not $5.58 billion.

Endnotes

[1]. “FCC National Broadband Map,” Federal Communications Commission, accessed December 12, 2024, https://broadbandmap.fcc.gov/home.

[2]. Ibid.

[3]. NTIA Data Explorer: Internet Use Survey (Non-Use of the Internet at Home, updated November 2023), https://www.ntia.gov/data/explorer#sel=noNeedInterestMainReason&demo=&pc=prop&disp=chart.

[4]. Jessica Dine, “The Digital Inclusion Outlook: What It Looks Like and Where It’s Lacking” (ITIF May 1, 2023), https://itif.org/publications/2023/05/01/the-digital-inclusion-outlook-what-it-looks-like-and-where-its-lacking/.

[5]. NTIA Data Explorer: Internet Use Survey (Non-Use of the Internet at Home, updated November 2023), https://www.ntia.gov/data/explorer#sel=tooExpensiveMainReason&demo=&pc=prop&disp=chart.

[6]. U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), “Broadband: National Strategy Needed to Guide Federal Efforts to Reduce Digital Divide” (Washington DC, May 2022), https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-22-104611.

[7]. Joe Kane, “Sustain Affordable Connectivity By Ending Obsolete Broadband Programs” (ITIF July 17, 2023), https://itif.org/publications/2023/07/17/sustain-affordable-connectivity-by-ending-obsolete-broadband-programs/.

[8]. “Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment (BEAD) Program,” BroadbandUSA: National Telecommunications and Information Administration, accessed June 2023, https://broadbandusa.ntia.doc.gov/taxonomy/term/158/broadband-equity-access-and-deployment-bead-program.

[9]. Jessica Dine and Joe Kane, “The State of US Broadband in 2022: Reassessing the Whole Picture” (ITIF, December 2022), https://itif.org/publications/2022/12/05/state-of-us-broadband-in-2022-reassessing-the-whole-picture/.

[10]. Jessica Dine and Joe Kane, “Broadband Myths: Is U.S. Broadband Service Slow?” (ITIF January 11, 2023), https://itif.org/publications/2023/01/11/broadband-myths-is-us-broadband-service-slow/.

[11]. Department of Housing and Urban Development “Housing Choice Vouchers Fact Sheet” (Washington DC), https://www.hud.gov/topics/housing_choice_voucher_program_section_8; Department of Agriculture, “Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)”(Washington DC), https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/supplemental-nutrition-assistance-program.

[12]. FCC, “Emergency Broadband Benefit” (Washington DC, December 2023), https://www.fcc.gov/broadbandbenefit.

[13]. FCC “FCC LAUNCHES AFFORDABLE CONNECTIVITY PROGRAM” (Washington DC, December 2023), https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/DOC-378908A1.pdf.

[14]. Ibid.

[15]. Ibid.

[16]. Ibid.

[17]. Ibid.

[18]. “Affordable Connectivity Program Dashboard,” Institute for Local Self-Reliance, https://acpdashboard.com/.

[19]. FCC, “Affordable Connectivity Program Has Ended” (Washington DC, June 2024), https://www.fcc.gov/sites/default/files/ACP-FAQs-Post-ACP-Ending.pdf.

[20]. Masha Abarinova, “Congress proposes $7B Affordable Connectivity extension,” Fierce Network, January 10, 2024. https://www.fierce-network.com/broadband/congress-proposes-7b-affordable-connectivity-extension.

[21]. HHS, “2024 Poverty Guidelines: 48 Contiguous States (all states except Alaska and Hawaii)” (Washington DC, 2024), https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/7240229f28375f54435c5b83a3764cd1/detailed-guidelines-2024.pdf.

[22]. Peter Christiansen, “Affordable Connectivity Program (ACP): Bridging the Digital Divide with Accessible Internet Solutions,” HighSpeedInternet, June 3, 2024, https://www.highspeedinternet.com/resources/what-is-affordable-connectivity-program.

[23]. Jericho Casper, “ACP Fallout: Wireline Retains Most, Wireless and Satellite Face Major Losses,” Broadband Breakfast, November 20, 2024, https://broadbandbreakfast.com/acp-fallout-wireline-retains-most-wireless-and-satellite-face-major-losses/.

[24]. For example, see: Paul Winfree, “Bidenomics Goes Online,” Economic Policy Innovation Center, January 8, 2024, https://epicforamerica.org/the-economy/bidenomics-goes-online-increasing-the-costs-of-high-speed-internet/.

[25]. Manudeep Bhuller et al., “The Internet, Search Frictions and Aggregate Unemployment,” NBER Working Paper Series, No. 30911 (February 2023), https://www.nber.org/papers/w30911.

[26]. Old ACP already made this kind of distinction, FCC, “FCC Acts to Provide Subsidy for Consumers in Certain High-Cost Areas” (Washington DC, August 4, 2023), https://www.fcc.gov/document/fcc-acts-provide-subsidy-consumers-certain-high-cost-areas-0.

[27]. Adrianne B. Furniss, “The Importance and Effectiveness of the Lifeline Program.” Benton Institute for Broadband & Society, August 28, 2023, https://www.benton.org/blog/importance-and-effectiveness-lifeline-program.

[28]. “Affordable Connectivity Program Dashboard,” https://acpdashboard.com/.

[29]. USAC Open Data (Universal Service Administrative Co.), accessed June 2023, https://opendata.usac.org/; ReConnect disbursements from USDA, ReConnect Loan and Grant Program, “Program Awardees,” USDA, accessed June 2023, https://www.usda.gov/reconnect; See also, Kane, “Sustain Affordable Connectivity By Ending Obsolete Broadband Programs.”

[30]. Tyler Cowen, “Commodity Taxes,” Marginal Revolution University, https://mru.org/courses/principles-economics-microeconomics/taxes-subsidies-definition-tax-wedge.

[31]. Joe Kane and Jessica Dine, “Consumers Are the Ones Who End Up Paying for Sending-Party-Pays Mandates” (ITIF, November 2022), https://itif.org/publications/2022/11/07/consumers-are-the-ones-who-end-up-paying-for-sending-party-pays-mandates/.

[32]. “Federal Communications Commission v. Consumers’ Research,” Scotusblog, https://www.scotusblog.com/case-files/cases/federal-communications-commission-v-consumers-research/.

Editors’ Recommendations

Related

January 13, 2025

To Do: Create a New and Improved Affordable Connectivity Program

September 23, 2022

Congress Should Prioritize the Affordable Connectivity Program for Broadband Funding

February 21, 2025