Which US Allies Are Most Likely to Face Trump Tariffs—and How Can They Avoid the Wrath of an “America First” Doctrine?

President-elect Trump believes the era of U.S.-led globalization has been harmful to America. One way he intends to change course is by imposing tariffs on nations that take advantage of U.S. goodwill and leadership. At greatest risk will be nations with low military budgets, high trade balances, policy barriers to reciprocal trade, and soft positions on China.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Key Takeaways

Contents

The History of “America Second” 4

Appendix 2: Rank-Ordered Composite and Subcategory Scores 12

Introduction

When a nation considers its economic prowess to be unassailable, it can afford to be magnanimous. And since the Cold War era, the United States has consistently made trade-offs that subordinated its trade and economic interests to its geopolitical and national-security objectives. Throughout the Cold War, America cut favorable trade deals with countries it wanted as strong allies, reduced tariffs on their imports, provided them foreign aid and technology transfers, and even encouraged U.S. companies to locate activity in their markets, all in the great geopolitical struggle to contain the Soviet threat. Even after the Soviet Union disintegrated, the Washington Consensus still counseled making techno-economic concessions to foreign nations to achieve foreign-policy goals.

As much as champions of the old Washington Consensus might long for that approach to continue, those days are gone. President-elect Trump’s “America First” agenda marks a turn toward a new doctrine—putting an end to one-sided trade deals, quitting the role of serving as the global policeman for countries unwilling to spend their own money to defend themselves, and not turning a blind eye to allied attacks on the U.S. economy and U.S. companies in the hope of maintaining comity despite the costs. And a key arrow in the U.S. quiver in the Trump administration will be tariffs. So, Washington’s “Massachusetts Avenue” internationalists will either have to get with the program or be relegated to the sidelines.

Trump’s “America First” agenda marks a turn toward a new doctrine of competitive realism.

Judging by Trump’s public statements and past actions as president, his America First doctrine will be directed first and foremost toward countries that free-ride off of America’s investments (in areas such as defense and pharmaceutical drug development); those that use our market openness to strengthen their economies (e.g., running chronic trade surpluses with the United States); those that enact policies that hurt the U.S. economy and U.S. companies; and those that kowtow to China to gain economic favors, rather than standing firm with America.

The Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) has developed an innovative ranking to assess U.S. allies’ risks of being subject to tariffs in the Trump administration using two variables, countries’ defense spending and their trade balance with the United States.[1] In this report, the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) expands on that analytical framework by developing our own model for assessing “Trump Risk” using four indicators:

1. defense spending,

2. trade balance,

3. a composite of measure of anti-U.S. trade and technology policies, and

4. willingness to resist China’s techno-economic predation.

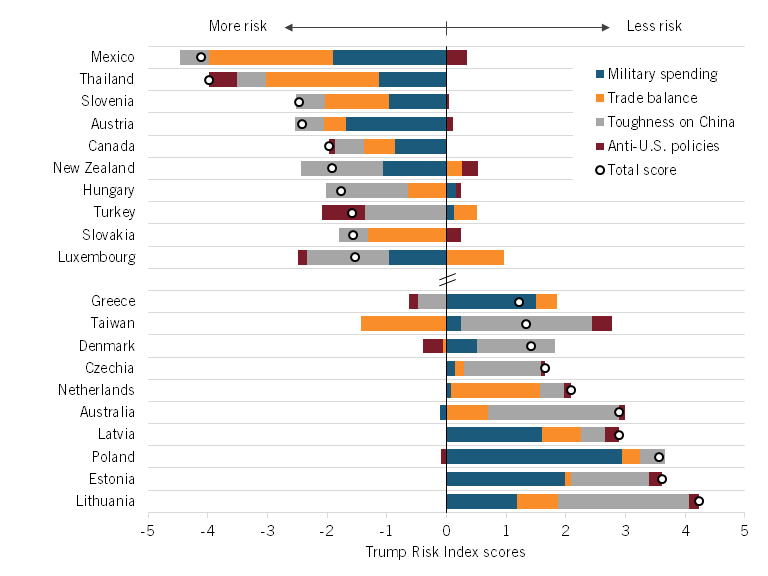

The resulting index covers 39 U.S. allies. Figure 1 shows the countries at highest and lowest risk of facing tariffs in the second Trump administration. See Appendix 1 for a detailed explanation of the methodology and sources. And see Appendix 2 for all 39 U.S. allies’ rank-ordered scores in each subcategory and the composite index.

Figure 1: U.S. allies at highest and lowest risk of tariffs in ITIF’s Trump Risk Index

The History of “America Second”

Before examining a nation’s risk, it’s worth a quick review of the prior approach to foreign policy. Call it “America Second.” In their effort to contain the Soviets, U.S. policymakers guided by the Washington Consensus consistently put U.S. economic interests in a subordinate position to U.S. foreign policy interests.

And while that approach was supported by the Washington Consensus, there were also detractors. As early as 1971, the U.S. Commission on Trade and Investment Policy cautioned that Washington was overemphasizing geopolitical considerations at the expense of U.S. economic interests.[2] The commission warned that the U.S. manufacturing base was declining as a result of the industry-targeting policies of other countries—and as a result of U.S. complicity with those policies. Perhaps the archetypal example of the United States favoring its geopolitical interests over its economic interests came in the trade conflicts with Japan in the late 1970s and 1980s, as Japan pursued a mercantilist, export-led economic growth strategy (just as China does today). Japan had implemented a number of policies designed to skew trade in its favor and to limit U.S. companies’ access to Japanese markets, including: imposing high tariffs, import quotas, and onerous regulations, inspections, and standards requirements on U.S. products; limiting U.S. ownership of Japanese enterprises; manipulating the yen’s value; and shutting U.S. companies almost entirely out of strategic markets, including autos, semiconductors, and mainframe computers—all while dumping below cost key products on U.S. markets. As a result, to take just one example, Japanese companies by 1984 had captured 60 percent of the U.S. semiconductor chip market.

In their effort to contain the Soviets, U.S. policymakers guided by the Washington Consensus consistently put U.S. economic interests in a subordinate position to U.S. foreign policy interests.

Pressure then mounted from the U.S. business community, labor, and Congress for the White House to file unfair trade complaints under the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and to declare Japan an unfair trader under U.S. law. But the U.S. policy community was torn about how much to pressure Japan. On one side were national security agencies (including the departments of State, Defense, and the National Security Council), along with the Treasury Department and the Council of Economic Advisors (both acting on the principals of neoclassical economics agencies). On the other side were the Commerce Department and the White House Office of United States Trade Representative (both guided by a more pragmatic approach to the economy). The attitude of diplomats and military leaders was that “Japan was our unsinkable aircraft carrier” and that U.S. trade and economic interests should take a backseat to geopolitical concerns.[3] As Assistant National Security Advisor Gaston Sigur insisted at the time, “We must have those bases. Now that’s the bottom line.”[4] The economists piled on. Alonzo McDonald, a Carter administration trade negotiator, argued for a more activist policy against Japan, but he complained about resistance from the neoclassical economists at Treasury and the Council of Economic Advisors (exactly the same sort of resistance they continue to mount today), lamenting that the economists had “lost all touch with reality; it’s heart surgery handled by a biologist.”[5]

With the denouement of the Cold War, the Clinton administration signaled a new strategic approach that would elevate economic concerns to stand alongside geopolitical and national security concerns. Clinton Secretary of State Warren Christopher told the Senate Foreign Relations Committee that “among the three pillars of the new administration’s approach to foreign policy, economic growth ranked first.”[6] As Andrew Bacevich observed in American Empire, in the new conventional wisdom emerging in the post–Cold War era, “national economic interests would not be considered ‘secondary’ or subordinated to national security interests.”[7] “Broadly construed,” national security would henceforth include “both economic and geopolitical concerns.”[8] To facilitate this reordering of priorities, President Clinton created the National Economic Council (NEC) as a counterpart to the National Security Council, and Robert Rubin, the NEC’s first chair before becoming Clinton’s Treasury secretary, observed that “the big change” with Clinton’s approach was that “the economic component of any problem gets on the table at the same time as other issues.”[9] Or, as Mickey Kantor, Clinton’s chief trade negotiator put it, “Trade and international economics have joined the foreign policy table.” As Bacevich writes, “Traditional distinctions between the nation’s physical security and its economic well-being were among the barriers that globalization swept aside.”[10]

But the temporary economic boom of the second half of the 1990s put these concerns on the back burner. And then September 11, 2001, firmly elevated geopolitical and national security concerns back to the top of the agenda. Once again, the United States retuned to emphasizing geopolitical and national security concerns at the expense of economic ones. In his autobiography Decision Points, former President George W. Bush writes that preventing another terrorist attack was his chief concern.

All too often, U.S. policymakers continue to trade economic interest for global foreign policy concerns, because the U.S. establishment thinks America’s economic position is so secure that it can afford to make concession after concession.

The Obama administration was not much different: Traditional national security officials ran the show. For example, during President Obama’s November 2009 visit to China to meet with President Jintao, Obama pledged closer technical collaboration and accelerated safety approval of China’s planned COMAC C909 commuter jet.[11] It’s not clear why the president promised to help China develop commercial jetliners, but the most likely reason is that he did so as a concession to secure China’s assistance in negotiating with the recalcitrant North Korean and Iranian regimes, or perhaps to soften the blow of recent U.S. arms sales to Taiwan.

Yet, while the United States has made such deals with geopolitical concerns top of mind, China and other nations have focused squarely on gaining economic advantage, which they parlay into military advantage. Indeed, months before the United States agreed to provide China technical assistance in developing a commercial jetliner, in a speech titled “Let the Large Aircraft of China Fly in the Blue Sky,” Chinese prime minister Win Jinbao articulated a Chinese vision for developing and producing its own commercial jets in direct competition with Boeing, even though China could readily afford to buy all the Boeing jets it needed and more with its $200 billion annual trade surplus.[12] Now China’s COMAC is ascendent while Boeing is struggling.

After 50 years of this, it’s still the same story. All too often, U.S. policymakers continue to trade U.S. economic interest for global foreign policy concerns because, just like the rich person who can afford to be altruistic, the U.S. establishment thinks America’s economic position is so secure that it can afford to make concession after concession. But the cumulative effect of so often trading economic interests for geopolitical ones has contributed to long-term structural economic decline, as ITIF’s Hamilton Index of Advanced Industry Competitiveness has documented.[13] Ironically, over time, this will only weaken America’s relative military security.

America First

President-elect Trump has never bought into previous administrations’ vision. Indeed, in April 2016, in his first policy speech as president, Trump stated:

It’s time to shake the rust off America’s foreign policy. It’s time to invite new voices and new visions into the fold, something we have to do. The direction I will outline today will also return us to a timeless principle. My foreign policy will always put the interests of the American people and American security above all else. It has to be first. Has to be. That will be the foundation of every single decision that I will make.[14]

It turns out that this was the foundation of some decisions Trump made in his first term, but not all. Many in his foreign policy establishment, especially Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin, were wedded to the prior system and actively resisted Trump’s efforts, as did the U.S. foreign policy establishment writ large.

But while the “globalists” in the first Trump administration exerted considerable influence, there is reason to believe that in Trump II, they will be fewer and farther between. For example, Secretary of State nominee Senator Marco Rubio (R-FL) is a China hawk in the best sense of the term. And among other goals, the 2024 Trump/Republican platform promised to “Rebalance Our Trade”; and “Become the Manufacturing Superpower.”[15] Trump also has signaled he intends to get tough on China, and he expects our allies to do the same. And he has long complained about allies free-riding on America by underinvesting in national defense.

Trump Risk Index Scores

So, given that Trump plans to elevate U.S. economic interests—and assuming his plans will include technologically advanced industries—what does that mean for other nations? While it’s not clear what the exact criteria will be as Trump decides whether nations are “with us” or “against us,” there is good reason to believe that four main areas will be front and center: defense spending; trade fairness, including trade balance and unfair trade practices; willingness to stand with the United States against China; and other factors and policies that harm U.S. interests, such as using antitrust to discriminate against U.S. technology companies, having a weak intellectual property regime, and maintaining cross-border data restrictions. Nations that the president views as being “against” America are more likely to be targeted for retaliatory action, including tariffs.

Therefore, ITIF has used these four indicators to rank nations on their likely risk of being subject to tariffs or other retaliatory measures in the second Trump administration. (See Appendix 1 for an explanation of sources and methodology.)

Table 1 lists countries’ weighted scores on each of the four composite indicators in ITIF’s Trump Risk Index, and their total scores. The more negative the score, the more likely it could be that President Trump will take action against a nation (all else being equal). Whereas, countries with positive scores are better positioned.

Table 1: U.S. allies’ scores in ITIF’s Trump Risk Index (negative scores represent higher risk)

|

Country |

Military Spending/GDP |

Trade Balance/GDP |

Toughness on China |

Anti-U.S. Policies |

Total Score |

|

Mexico |

-1.91 |

-2.07 |

-0.48 |

0.34 |

-4.12 |

|

Thailand |

-1.14 |

-1.89 |

-0.48 |

-0.47 |

-3.98 |

|

Slovenia |

-0.97 |

-1.07 |

-0.48 |

0.04 |

-2.48 |

|

Austria |

-1.69 |

-0.37 |

-0.48 |

0.11 |

-2.42 |

|

Canada |

-0.86 |

-0.52 |

-0.48 |

-0.11 |

-1.98 |

|

New Zealand |

-1.07 |

0.25 |

-1.37 |

0.27 |

-1.92 |

|

Hungary |

0.16 |

-0.65 |

-1.37 |

0.09 |

-1.78 |

|

Turkey |

0.13 |

0.37 |

-1.37 |

-0.71 |

-1.58 |

|

Slovakia |

0.01 |

-1.32 |

-0.48 |

0.23 |

-1.57 |

|

Luxembourg |

-0.97 |

0.97 |

-1.37 |

-0.15 |

-1.53 |

|

Spain |

-0.99 |

0.43 |

-0.48 |

-0.30 |

-1.34 |

|

Portugal |

-0.61 |

-0.03 |

-0.48 |

0.05 |

-1.08 |

|

Montenegro |

0.03 |

0.39 |

-1.37 |

0.16 |

-0.78 |

|

Albania |

0.05 |

0.52 |

-1.37 |

0.09 |

-0.71 |

|

Italy |

-0.70 |

-0.16 |

0.41 |

-0.27 |

-0.71 |

|

Germany |

0.17 |

-0.14 |

-0.48 |

-0.25 |

-0.69 |

|

Philippines |

-1.03 |

0.13 |

0.41 |

0.09 |

-0.40 |

|

Bulgaria |

0.26 |

0.08 |

-0.48 |

-0.14 |

-0.29 |

|

Croatia |

-0.26 |

0.43 |

-0.48 |

0.15 |

-0.16 |

|

United Kingdom |

0.46 |

0.48 |

-0.48 |

-0.40 |

0.06 |

|

Norway |

0.28 |

0.33 |

-0.48 |

0.00 |

0.13 |

|

South Korea |

1.12 |

-0.41 |

-0.48 |

-0.07 |

0.16 |

|

France |

0.09 |

0.27 |

0.41 |

-0.56 |

0.20 |

|

North Macedonia |

0.31 |

0.00 |

-0.48 |

0.48 |

0.32 |

|

Japan |

-1.10 |

-0.09 |

1.30 |

0.25 |

0.36 |

|

Sweden |

0.20 |

-0.09 |

0.41 |

0.08 |

0.61 |

|

Belgium |

-0.96 |

1.11 |

0.41 |

0.06 |

0.63 |

|

Romania |

0.35 |

0.17 |

0.41 |

0.00 |

0.94 |

|

Finland |

0.57 |

-0.05 |

0.41 |

0.22 |

1.16 |

|

Greece |

1.50 |

0.36 |

-0.48 |

-0.15 |

1.22 |

|

Taiwan |

0.24 |

-1.44 |

2.20 |

0.34 |

1.33 |

|

Denmark |

0.52 |

-0.06 |

1.30 |

-0.34 |

1.42 |

|

Czechia |

0.14 |

0.14 |

1.30 |

0.06 |

1.65 |

|

Netherlands |

0.08 |

1.49 |

0.41 |

0.12 |

2.09 |

|

Australia |

-0.10 |

0.69 |

2.20 |

0.10 |

2.88 |

|

Latvia |

1.59 |

0.66 |

0.41 |

0.22 |

2.88 |

|

Poland |

2.93 |

0.31 |

0.41 |

-0.10 |

3.56 |

|

Estonia |

1.98 |

0.11 |

1.30 |

0.21 |

3.60 |

|

Lithuania |

1.18 |

0.69 |

2.20 |

0.16 |

4.22 |

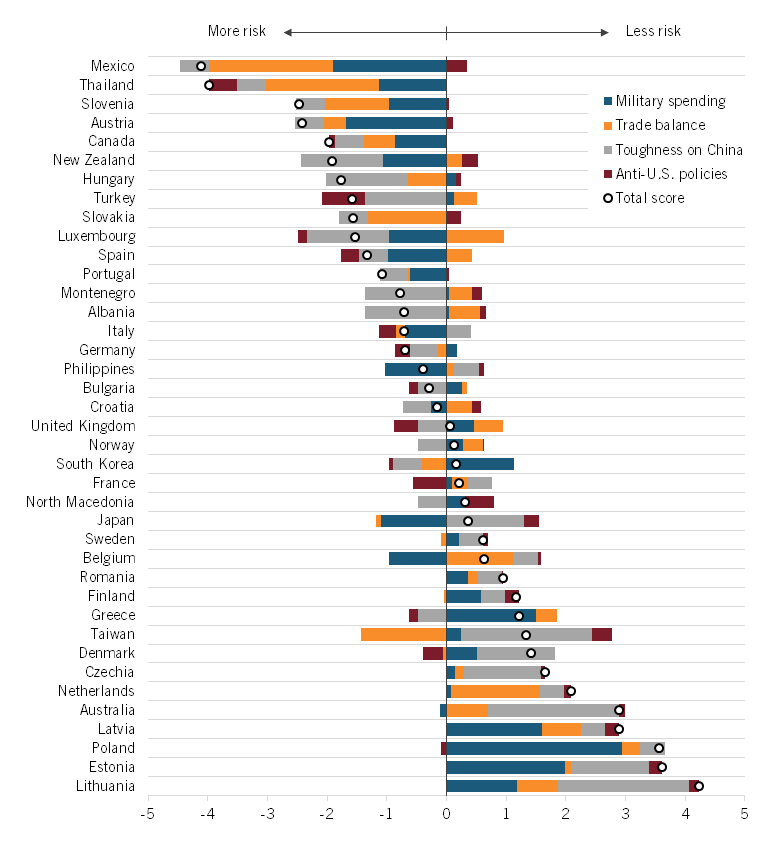

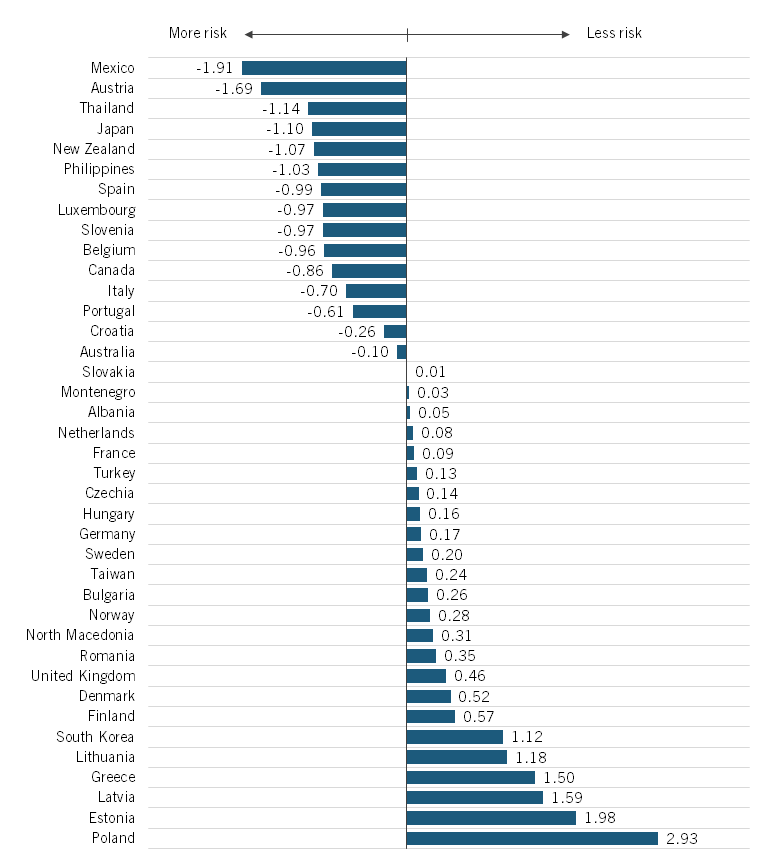

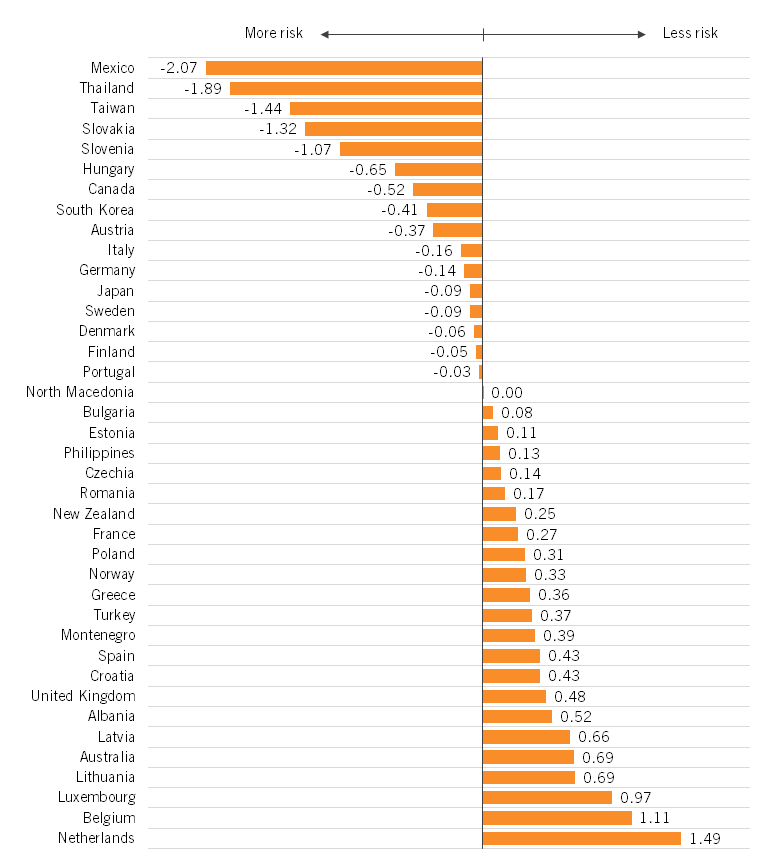

The five countries that are most at risk in ITIF’s index are Mexico, Thailand, Slovenia, Austria, and Canada in that order—with Mexico and Thailand in a class by themselves. (See figure 1 and figure 2.) All five are below the group average in their defense spending as a share of GDP (figure 3). All run trade surpluses with the United States, Mexico and Thailand having the biggest (figure 4). All of them, in ITIF’s estimation of the Trump administration’s likely view, are “soft” on China and resist fully allying themselves with the United States to resist China’s rising military, foreign policy, and techno-economic hegemony (figure 5). And on an array of mercantilist policies that proposed or enacted affecting technologically advanced industries, Canada and Thailand are below average, but the other three are not without some problems (figure 6). Other nations ranking in the top 10 overall in terms of their risk of facing tariffs or other retaliation from the Trump administration are New Zealand, Hungary, Turkey, Slovakia, and Luxembourg.

At the other end of the spectrum, the five countries that are farthest into the “safer zone” are Lithuania, Estonia, Poland, Latvia, and Australia. All have above-average military spending, with the exception of Australia, which is close to the average. All run trade deficits with the United States. All have made some efforts to push back against Chinese predation. And all except Poland are above average on a range of protectionist measures against the United States. Other top 10 nations are Netherlands, Czechia, Denmark, Taiwan, and Greece.

What Should Nations Do?

So far, Trump has not proved that he will be fully consistent in his words and actions. But it appears to be a safe bet that nations should take Trump seriously. The natural response for many countries targeted by Trump will be to protest and insist that they will not cave into this kind of untoward pressure. But while that might be good from the perspective of domestic politics, it is likely to be bad domestic policy.

For those nations whose scores are low, put them at greater risk of facing tariffs or other retaliatory measures from the Trump administration, there are steps all could take to show the president-elect they intend to be better allies to America. To start with, they can commit to raising their defense spending if it is low, starting with actual increases in appropriations for 2025. There is in fact no reason for them to free ride on U.S. defense spending. It is selfish and unfair, and it is time for it to stop.

Second, they can signal that they will stop siding with China or positioning themselves on the fence instead of standing up for freedom and democracy. That would entail, among other steps, passing laws limiting inward foreign investment from China, joining with the United States and its core allies in sharing commercial counterintelligence, standing up to China’s wolf-warrior diplomacy and other bullying, and joining America on export controls. Of course, this will be hard to do for some nations that are accustomed to believing they can or should try to “have their cake and eat it too”—i.e., choosing not to stand up to rampant Chinese techno-economic mercantilism in the hope that they will benefit from having some level of access to China’s huge domestic market. But again, such action is selfish and short-sighted, and to the extent pressure from the Trump administration makes it easy for those nations’ domestic politics to come around to a tougher China position, Trump is doing them a favor.

The natural response for many countries targeted by Trump will be to protest and insist that they will not cave into this kind of untoward pressure. But while that might be good from the perspective of domestic politics, it is likely to be bad domestic policy.

Third, and most difficult, nations can immediately shelve proposals or repeal existing rules designed to harm American companies, such as digital services taxes and restrictive antitrust laws modeled after the EU’s Digital Markets Act; they can crack down on IP and software theft; they can boost pharmaceutical reimbursement rates; and they can embrace the free flow of data across their national borders. Nations that have put in place these policies and practices clearly have done so because they believe they benefit will economically. Why not unfairly tax U.S. digital companies? That is free money for their national treasuries.[16] Why not impose onerous antitrust laws on American companies? That will give their weaker domestic companies a leg up. Why not avoid paying very much for drugs despite the fact that those revenues support new drug discovery?[17] It’s easier to free ride. You get the picture. Nations can fix these problems with the stroke of a pen. It simply requires political will.

The fourth step—reducing nations’ trade deficits with the United States—is harder, in part because trade balances are the product of many factors, and the private sector plays a key role. But even here, there are some easy things nations should do. First, countries can ensure that their tariffs on U.S. imports are broadly reciprocal and equivalent to U.S. tariffs on their exports. They can encourage their companies to buy more from American companies and less from Chinese companies. To the extent that nations subsidize exports, they can cease doing so. And to the extent they manipulate their currencies for competitive advantage, they can stop.

None of this is to say that the United States can blame other nations for all of its trade deficit. The insistence of past administrations, pressured by the Treasury Department and Wall Street, to keep a strong dollar has resulted in a much larger trade deficit than would otherwise be the case. And the lack of a strategic industrial policy has allowed a hollowing out of U.S. production, fewer exports, and more imports. But at the end of the day, President-elect Trump and his team no doubt will be looking at the ways foreign nations contribute to these problems. And foreign nations should take his concerns seriously if they want to avoid being targets, because we are entering a new era of competitive realism.[18]

Appendix 1: Methodology

ITIF’s model covers the same 37 allied nations that CSIS included in its analysis. In addition, we added Austria and Mexico. To estimate a Trump risk score, we used the two main indicators from the CSIS report—military spending as a share of GDP and trade deficit. In addition, ITIF included two other indicators: toughness on China and other anti-U.S. taxes and policies that amount to trade barriers.

These four main indicators are comprised of 11 variables:

1. Military expenditures as a share of GDP;

2. Trade balance as a share of GDP;

3. Other taxes and policies acting as trade barriers:

a. The 2024 USTR Watch List (Priority Watch List = 0, Watch List = 1, Not Listed = 2);

b. The extent to which nations have enacted pharmaceutical price controls (Low = 3, Moderate = 2, High = 1);

c. 2018 GDP per capita adjusted prescription price levels compared to the United States;

d. 2017 rates of unlicensed software installation;

e. 2017 commercial value of unlicensed software ($M);

f. The number of national data regulations countries have enacted;

g. Antitrust laws similar to the EU’s Digital Markets Act that countries have proposed or enacted (Yes = 0, No = 1);

h. Digital services taxes (Yes = 0, No = 1); and

4. Toughness on China (5 = Tough, 1 = Weak).

The data and information sources for those variables included the following:

▪ The CSIS analysis.[19]

▪ The World Bank’s World Development Indicators.[20]

▪ The U.S. Trade Representative’s 2024 Special 301 Report.[21]

▪ ITIF’s 2016 report, “Contributors and Detractors: Ranking Countries’ Impact on Global Innovation.”[22]

▪ ITIF’s 2023 report, “The Hidden Toll of Drug Price Controls: Fewer New Treatments and Higher Medical Costs for the World.”[23]

▪ The 2018 BSA Global Software Survey.[24]

▪ ITIF’s 2021 report, “How Barriers to Cross-Border Data Flows Are Spreading Globally, What They Cost, and How to Address Them.”[25]

▪ VATCal’s global tracker of digital services taxes.[26]

We used various official and secondary sources to determine whether nations have enacted or are considering antitrust laws like the EU’s Digital Markets Act. And we used various primary and secondary sources to assess nations’ policies towards China, but we ultimately assigned scores for this variable using our own qualitative assessments.

The original values for the following variables were then inverted to make scores positive or negative according to how the Trump administration will likely view them: 2018 GDP per capita adjusted prescription price levels compared to the United States; 2017 rates of unlicensed software installation; 2017 commercial value of unlicensed software; and number of national data regulation.

The values for the 11 variables were then standardized to obtain a comparable z-score. Once standardized, the 11 variables were separated into the four categories in the Trump Risk Score table: military expenditures as a share of GDP, trade balance as a share of GDP, toughness on China, and other trade-barrier factors. The first three categories capture military expenditures as a share of GDP, trade balance as a share of GDP, and how tough a nation is on China, respectively. The other trade-barrier factors category is the average of the remaining 8 variables’ z-score. Due to its 0 and 1 metric, the negative z-scores for the USTR 301 Watchlist were divided by 2 to prevent them from skewing the composite “other factors” score negatively. Similarly, the positive z-scores for DMA laws were also divided by 2 to prevent skewing the composite “other factors” score positively.

The total score in the resulting Trump Risk Index was calculated by summing the weighted z-scores of the four categories. Military expenditures as a share of GDP have a weight of 1, trade balance as a share of GDP have a weight of 0.75, toughness on China has a weight of 1, and other trade-barrier factors have a weight of 0.75. The nations with the highest resulting scores are less at risk than those with lower scores.

Appendix 2: Rank-Ordered Composite and Subcategory Scores

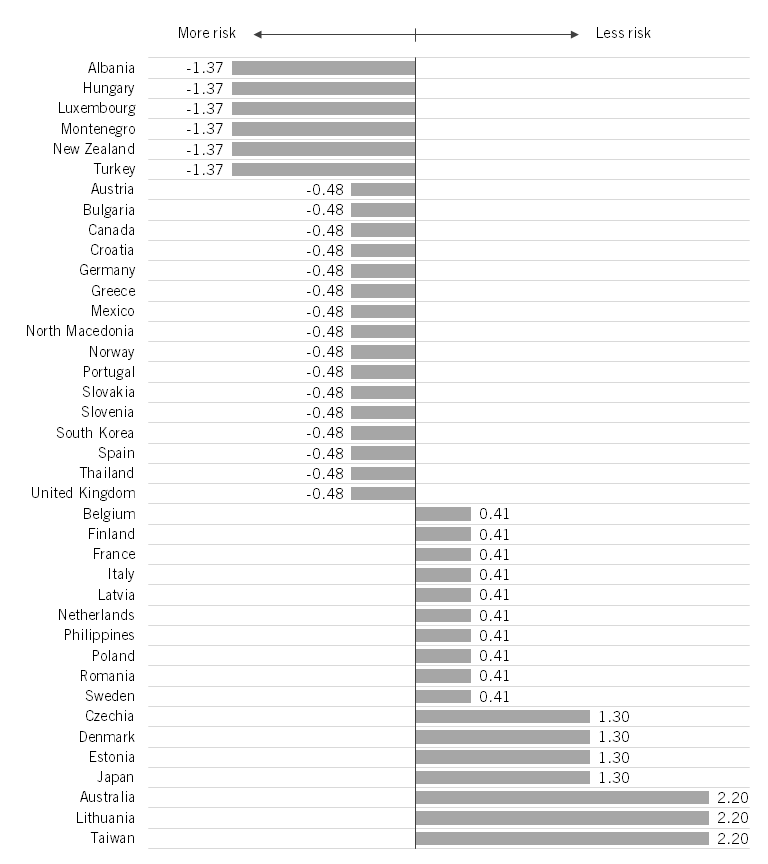

Figure 2: Composite scores

Figure 3: Military spending scores

Figure 4: Trade balance scores

Figure 5: Toughness on China scores

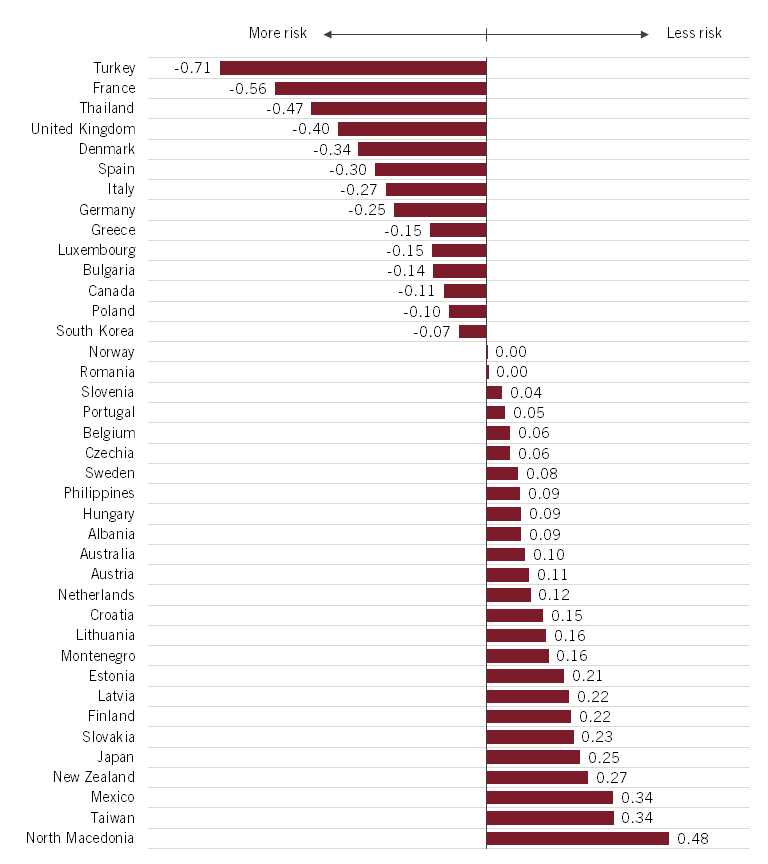

Figure 6: Anti-U.S. policy scores

About the Authors

Dr. Robert D. Atkinson (@RobAtkinsonITIF) is the founder and president of ITIF. His books include Technology Fears and Scapegoats: 40 Myths About Privacy, Jobs, AI and Today’s Innovation Economy (Palgrave McMillian, 2024), Big Is Beautiful: Debunking the Myth of Small Business (MIT, 2018), Innovation Economics: The Race for Global Advantage (Yale, 2012), Supply-Side Follies: Why Conservative Economics Fails, Liberal Economics Falters, and Innovation Economics Is the Answer (Rowman Littlefield, 2007), and The Past and Future of America’s Economy: Long Waves of Innovation That Power Cycles of Growth (Edward Elgar, 2005). He holds a Ph.D. in city and regional planning from the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

Trelysa Long is a policy analyst at ITIF. She was previously an economic policy intern with the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. She earned her bachelor’s degree in economics and political science from the University of California, Irvine.

About ITIF

The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) is an independent 501(c)(3) nonprofit, nonpartisan research and educational institute that has been recognized repeatedly as the world’s leading think tank for science and technology policy. Its mission is to formulate, evaluate, and promote policy solutions that accelerate innovation and boost productivity to spur growth, opportunity, and progress. For more information, visit itif.org/about.

Endnotes

[1]. Victor Cha, “How Trump Sees Allies and Partners” (Center for Strategic and International Studies, November 2024), https://www.csis.org/analysis/how-trump-sees-allies-and-partners.

[2]. Clyde Prestowitz, The Betrayal of American Prosperity: Free Market Delusions, America’s Decline, and How We Must Compete in the Post- Dollar Era (New York: Free Press, 2010), 94.

[3]. Ibid, 101.

[4]. Ibid.

[5]. Judith Stein, Pivotal Decade: How the United States Traded Factories for Finance in the Seventies (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010), 255.

[6]. Andrew Bacevich, American Empire: The Realities and Consequences of U.S. Diplomacy (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002).

[7]. Ibid.

[8]. Ibid.

[9]. Ibid.

[10]. Ibid.

[11]. Clyde Prestowitz, “The $64 Trillion Question (Part 1),” New Republic, June 22, 2010, http://www.tnr.com/article/economy/75733/the-64-trillion-question-part-1/.

[12]. Clyde Prestowitz, The Betrayal of American Prosperity: Free Market Delusions, America’s Decline, and How We Must Compete in the Post-Dollar Era (New York: Free Press, 2010), p. 94.

[13]. Robert Atkinson and Ian Tufts, “The Hamilton Index, 2023: China Is Running Away With Strategic Industries” (ITIF, December 2023), https://itif.org/publications/2023/12/13/2023-hamilton-index/.

[14]. Ryan Teague Beckwith, “Read Donald Trump’s ‘America First’ Foreign Policy Speech,” TIME, April 27, 2016, https://time.com/4309786/read-donald-trumps-america-first-foreign-policy-speech/.

[15]. 2024 Republican Party Platform, https://www.donaldjtrump.com/platform.

[16]. Joe Kennedy, “Two Reasons Digital Services Taxes Are Attractive—and Five Reasons They’re Still Wrong,” ITIF Innovation Files commentary, June 4, 2020, https://itif.org/publications/2020/06/04/2-reasons-digital-services-taxes-are-attractive-5-reasons-theyre-wrong/; Joe Kennedy, “Digital Services Taxes: A Bad Idea Whose Time Should Never Come” (ITIF, May 2019), https://itif.org/publications/2019/05/13/digital-services-taxes-bad-idea-whose-time-should-never-come/.

[17]. Trelysa Long and Stephen Ezell, “The Hidden Toll of Drug Price Controls: Fewer New Treatments and Higher Medical Costs for the World” (ITIF, July 2023), https://itif.org/publications/2023/07/17/hidden-toll-of-drug-price-controls-fewer-new-treatments-higher-medical-costs-for-world/.

[18]. Robert Atkinson and Nigel Cory, “Time for Competitive Realism” (ITIF, May 2023), https://itif.org/publications/2023/05/05/time-for-competitive-realism/.

[19]. Cha, “How Trump Sees Allies and Partners.”

[20]. World Bank Group, DataBank, “World Development Indicators,” accessed November 2024, https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators.

[21]. Office of the United States Trade Representative, 2024 Special 301 Report, https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/2024%20Special%20301%20Report.pdf.

[22]. Stephen Ezell, “Contributors and Detractors: Ranking Countries’ Impact on Global Innovation” (ITIF, January 2016), https://www2.itif.org/2016-contributors-and-detractors.pdf.

[23]. Trelysa Long and Stephen Ezell, “The Hidden Toll of Drug Price Controls: Fewer New Treatments and Higher Medical Costs for the World” (ITIF, July 2023), https://itif.org/publications/2023/07/17/hidden-toll-of-drug-price-controls-fewer-new-treatments-higher-medical-costs-for-world/.

[24]. BSA | The Software Alliance, “Software Management: Security Imperative, Business Opportunity,” June 2018, https://gss.bsa.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/2018_BSA_GSS_Report_en.pdf.

[25]. Nigel Cory and Luke Dascoli, “How Barriers to Cross-Border Data Flows Are Spreading Globally, What They Cost, and How to Address Them” (ITIF, July 2021), https://itif.org/publications/2021/07/19/how-barriers-cross-border-data-flows-are-spreading-globally-what-they-cost/; “A Global View of Barriers to Cross-Border Data Flows,” data visualization, https://itif.org/publications/2021/07/19/global-view-barriers-cross-border-data-flows/.

[26]. Jacinta Caragher, “Digital Services Taxes DST—global tracker,” VATCalc, November 14, 2024, https://www.vatcalc.com/global/digital-services-taxes-dst-global-tracker/.