Growing Advanced Industries in the United Kingdom Will Be a Heavy Lift for Starmer’s Labour Government

As part of their plans to kickstart economic growth in the United Kingdom, incoming Prime Minister Keir Starmer and his Labour government have pledged to introduce a “new industrial strategy.” The plan calls for focusing on vital sectors such as autos and life sciences while being clear-eyed about where the United Kingdom enjoys competitive advantages over other countries, such as its research universities and advanced manufacturing capabilities.

This is all to the good, as economic policy agendas go. But make no mistake: The United Kingdom would have a lot of ground to make up in advanced industries just to get back to where it stood in the 1980s. In fact, at last count, the United Kingdom was punching 33 percent below its economic weight class in a global index of advanced-industry performance created by the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation.

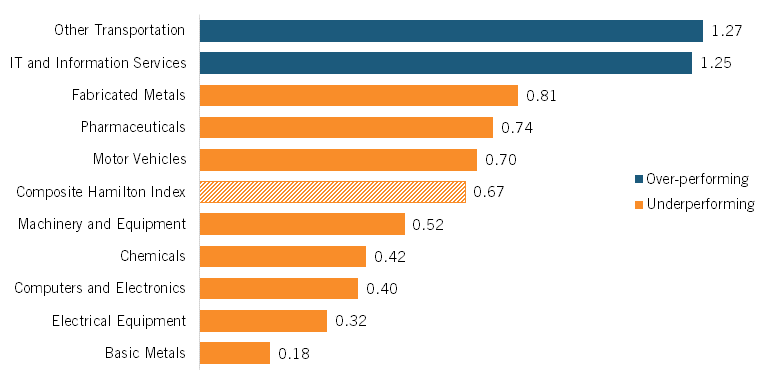

ITIF’s Hamilton Index covers the motor vehicle and pharmaceuticals industries that the incoming Labour government has targeted, plus eight others: chemicals, basic metals, fabricated metals, machine equipment, other transportation equipment (such as trains and rockets), electrical equipment, computers, and IT services.

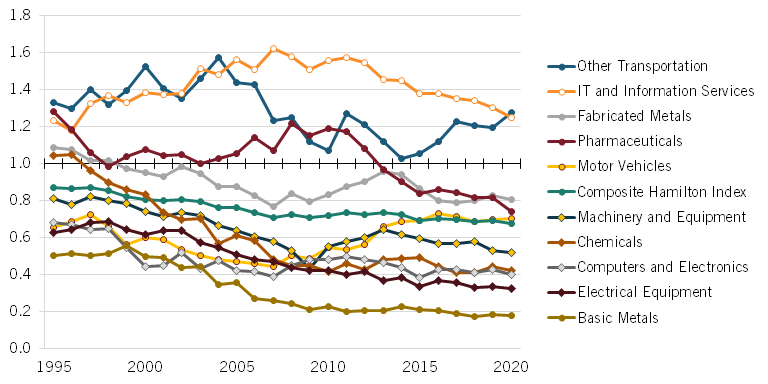

The United Kingdom’s output in these industries has been in a long, steady decline as a share of its national economy. Notably in the context of Labour’s plans, the United Kingdom’s motor vehicles industry produced 30 percent less than the size-adjusted global average in 2020 (the last year for which global industry data is available from the OECD). Meanwhile, the United Kingdom’s pharmaceuticals industry was 26 below average, having skidded from 28 percent above average in 1995.

ITIF uses an analytical statistic known as a “location quotient” (LQ), which is a ratio measuring how any region’s level of industrial specialization compares to a larger geographic unit—in this case, a nation relative to the rest of the world. (An LQ greater than 1 means the country’s share of global output in an industry is greater than the global average; and an LQ less than 1 means a country’s share is less than the global average.) By this measure, the United Kingdom’s advanced industries altogether performed 33 percent below the global average in 2020—worse than nations such as India, Mexico, Poland, Turkey, and Russia.

Figure 1: The United Kingdom’s relative historical performance in Hamilton industries (LQ trends)

To be sure, there were a couple of relative bright spots for the United Kingdom, such as its IT services industry (including software, AI, and e-commerce), which was 25 percent stronger than the size-adjusted global average. But the United Kingdom is fading from view in absolute terms. For perspective, consider that the United Kingdom’s IT services output in 2020 amounted to a mere 4 percent global market share. Across all 10 industries in ITIF’s index, the United Kingdom’s global market share had dropped by nearly half since the turn of the century—from 4 percent in 2000 to just 2.1 percent in 2020.

Figure 2: The United Kingdom’s relative performance in Hamilton Index industries (2020 LQ)

The question now is whether Labour’s efforts will be enough to spark a comeback. The detailed agendas Labour has trumpeted for the automotive sector and the life sciences sector call for providing stability and certainty for innovation by taking a long-term approach to supporting public and private R&D, bolstering skills by replacing the United Kingdom’s apprenticeship levy with a growth and skills levy, and boosting exports. If implemented as described, these plans will represent good first steps, but the scale of the challenge—especially in the face of the roaring Chinese advanced-technology juggernaut—will require a much stronger response.

First, the new government should significantly expand the United Kingdom’s research and development (R&D) tax credit while expanding the eligible capital spending. The United Kingdom ranks 20th of 34 countries in R&D tax-incentive generosity. If it wants to match Ireland as the 5th most generous, it would need to boost its credit by 155 percent. The government could establish a capital grant and/or tax credit program to help fund investments in new or expanded advanced manufacturing facilities in the United Kingdom.

The United Kingdom also should increase funding for university R&D by two-thirds, which would match industrial powerhouse Germany as a share of GDP, but it should target the funding toward key technology areas identified in partnership with U.K. industry, and make the support contingent on universities working closely with industry and entrepreneurs.

Finally, the new government should double down on the United Kingdom’s existing strength in the IT sector. Leading firms such as Monzo, Deliveroo, and Moneybox, already call the United Kingdom home, and global players such as Google and Scale AI are making significant investments in the United Kingdom, signaling further growth potential. It will be easier to capitalize on this opportunity now that the United Kingdom is no longer part of the EU—as long as the new government avoids the mistake of importing the panoply of innovation-killing IT regulations that the EU specializes in creating.

The United Kingdom is unlikely anytime soon to be as strong in advanced industries as Germany, Israel, or Korea. But with the right policies, it can at least aspire to move up the standings and surpass the United States, on a pound-for-pound basis, relative to the size of their respective economies.

Editors’ Recommendations

December 13, 2023