BEAD Report: Grading States’ Initial Proposals for Federal Broadband Funds

Congress has allocated $42.5 billion to bridge America’s digital divide through the Broadband Equity, Access and Deployment (BEAD) program. To achieve that goal, states and territories must carefully craft plans to use their shares of the funds to the greatest possible benefit.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Key Takeaways

Contents

States Should Practice True Tech Neutrality 4

States Should Not Label Locations as “Unserved” Based Solely on Their Covering Technology 5

States Should Create a Regulatory and Programmatic Environment That Fosters Efficiency 6

States Should Waive All Existing State Laws That Preference—or Disadvantage—Municipal Providers 7

States Should Build Strong, Collaborative Structures to Govern Their Broadband Approach. 8

States Should Address Digital Inclusion Within BEAD. 9

States Should Account for Community Impact in Their BEAD Subgrantee Selection Process 9

Introduction

The Broadband Equity, Access and Deployment (BEAD) program, funded through the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) in 2021, has dominated the broadband infrastructure news cycle for some time now—and for good reason. If all goes well, the $42.5 billion program run by the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) should successfully fund complete broadband coverage across the United States.[1] Much of the burden of that “if” rests on the shoulders of funding recipients: Under the program, each eligible state and territory is both allocated its own funds and tasked with creating an individual plan for the use of those funds.

The first half of 2024 is a critical juncture because states are now soliciting feedback and approval on their two-volume Initial Proposals.[2] These proposals explain in detail how states will allocate funding, what types of broadband networks they will fund, and myriad other details of the process.[3] Volume 1 of each Initial Proposal includes a state’s accounting of its current broadband funding, lists of locations that are eligible or under consideration for BEAD funding, and a description of the challenge process through which certain entities can dispute the eligibility status of various locations.[4] Volume 2 includes (but is not limited to) each state’s articulation of its plan for selecting Internet service providers (ISPs) to participate as BEAD subgrantees, its method of soliciting local input and addressing constituents’ particular needs, and its overall broadband objectives.[5]

As of April 2024, every eligible state and territory has submitted both volumes to NTIA for approval and precipitated an iterative process of requests for edits and resubmission.[6] So far, most states have received approval from NTIA on Volume 1 of their Initial Proposal (and are therefore free to start their challenge process) and four states have had both their Volume 1 and Volume 2 approved. States cannot proceed with their subgrantee selection and truly embark on the BEAD program until NTIA approves both volumes of their Initial Proposals.

These proposals, in addition to indicating the future performance of BEAD, will dictate the future of the U.S. digital divide. BEAD is the largest single program meant to address the digital divide, an ongoing problem whose causes today extend far beyond infrastructure gaps. “Non-adopters” that do not subscribe to broadband most often cite reasons such as lack of interest or unaffordability.[7] Though there are digital inclusion programs specifically designed to address these barriers—particularly the Digital Equity Act programs—their funding is a fraction of BEAD’s.[8] BEAD, therefore, represents an important potential source of funding for critical and underfunded digital inclusion efforts such as digital navigation services, which provide personalized assistance to the technology hesitant, and programs to increase trust and digital literacy among offline populations. Mismanaged BEAD funding comes at the expense of both completing deployment and addressing all of the digital divide’s root causes—and ultimately, our ability to give every American the opportunity to get online.

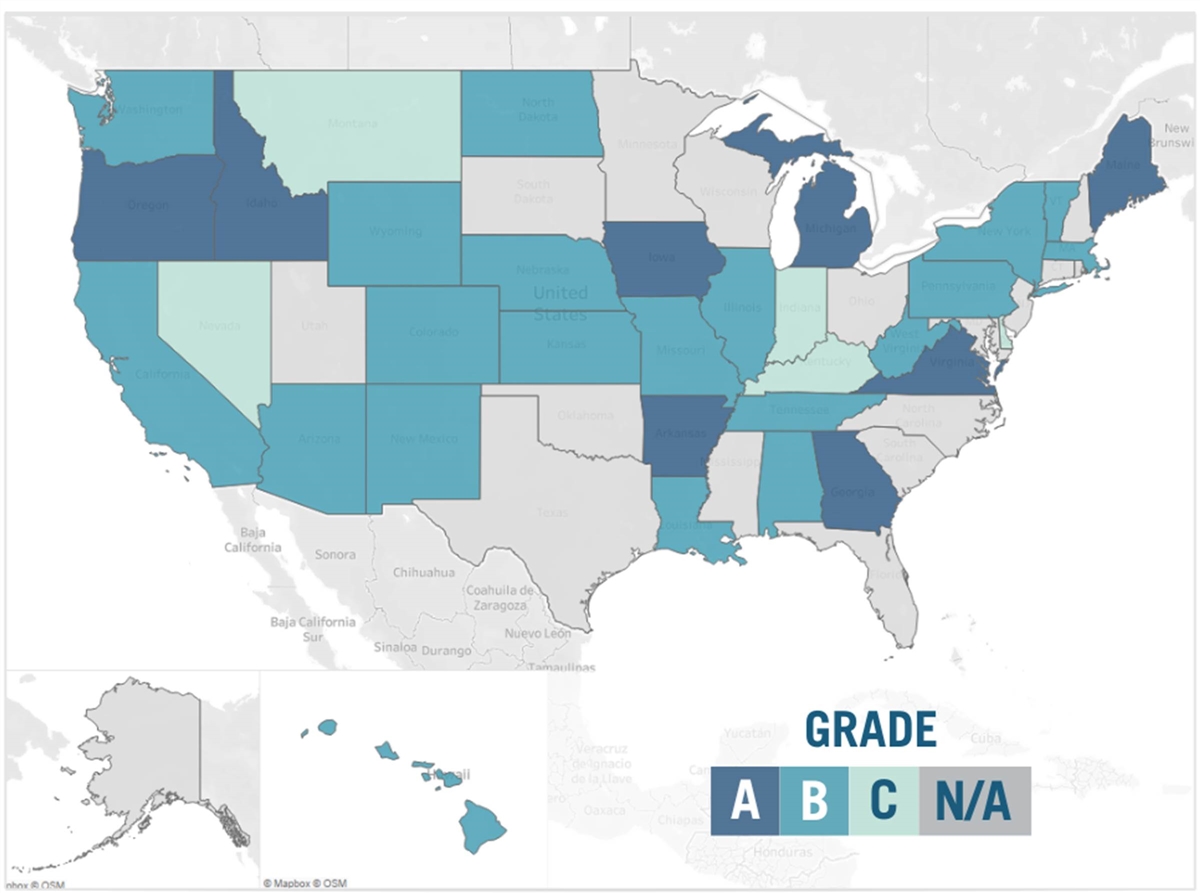

As states’ Initial Proposals come out, the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) is rating them on their adherence to three major criteria that will ensure BEAD funding is used to the greatest possible benefit, with the aim of encouraging course-correction by states that need it and highlighting those that are doing well. (See the accompanying data visualization.) First, states should plan to rely on a range of technologies to maximize their broadband coverage, from fiber optic networks to low Earth orbit (LEO) satellites where the cost of a fixed connection is prohibitive. Second, states should create a streamlined regulatory environment that minimizes funds wasted on overcoming disjointed policies or inefficient regulations. Third, states should express a focus on—and articulate a plan for—digital inclusion within their BEAD plans.

Figure 1: Overall state grades as of May 13, 2024. (Click map for interactive data visualization.)

Methodology

This report explains and accompanies the graphic that depicts states’ scores in both the individual categories and as an aggregate grade. The analysis is limited to U.S. states, not other eligible territories, to limit the possible universe of information. At the time of this report, 34 states are included in the grading (with the acknowledgement that revisions might be necessary if their approved Volume 2 submissions have significant changes). Though every effort was made to use the most recent state draft, in certain cases, states may have posted Initial Proposals at various stages of drafting—and only one state had finalized its Volume 2 Initial Proposal when it was graded. More states will be added as their submissions are graded. This report therefore attempts to emphasize higher-level trends over details that may be more subject to change (though that is not always possible), and it should be viewed as the beginning of an iterative process rather than a final product.

The following explains the breakdown of criteria for each of the three grading categories and highlights some examples of strong performances in each. Each of the three criteria is broken into four subcriteria, and states earn one point for each subcriteria they complete and zero for those they do not. In total, therefore, a state can have up to four points in each umbrella category. States that earn over three points achieve an A, states with more than two points receive a B, and those with two or fewer points earn a C for that category. Though the aggregate of these three grades is also calculated as a quick indication of each state’s overall standing, the individual category grades provide more details on where each state is strong and where it needs improvement.

This grading exercise is meant to alert those states whose current trajectories risk costing them program success down the line. It highlights specific states’ missteps to explain why and how particular actions should be corrected. Similarly, it provides examples of a few exceptional state performances to encourage other states to mimic those behaviors. These rankings are also meant to supplement, not replace, NTIA’s more thorough and official assessment of each state plan. Our criteria generally build on the requirements set out by NTIA, though they disagree in parts—most notably on NTIA’s push for maximizing fiber coverage across each state.[9] Though NTIA is a highly responsible steward of the many programs it administers, its established preference for fiber networks risks hamstringing states that adhere too strictly to that at the expense of digital inclusion programs or even complete coverage.

Scoring Criteria

States Should Practice True Tech Neutrality

Though fiber optic networks are the most advanced technology available, and perhaps preferable ceteris paribus, ITIF and many other groups have long argued that reliance on a mix of technologies is the best and most feasible—indeed, perhaps the only way—to close the digital divide.[10] From the general consumer’s perspective, a fiber connection’s performance is not materially different from that of, for example, a cable connection using DOCSIS 4.0. Everyday use does not yet require fiber speeds, and prioritizing meeting hypothetical future needs with limited funds comes at the expense of closing the digital divide today, especially since we are unlikely to see another allocation of funding as large as BEAD anytime soon (if at all). In a country where some of the population is still entirely offline, it is irresponsible to push more expensive fiber coverage that is less likely to stretch to reach every community. If it costs as much to bring fiber to a single remote home as it does to upgrade entire communities’ networks or to connect dozens of households, it is likewise irresponsible to choose the former when LEO satellite exists as a cost-effective solution.

Beyond maximizing broadband coverage, states should ideally preserve some BEAD funds to help address the drivers of the digital divide beyond deployment. Every excess dollar put toward fiber where another reliable technology could suffice is a dollar less to spend on inclusion activities or addressing other barriers that consumers face. States should prioritize achieving universal coverage with technologies that meet current needs while retaining funds to address inclusion activities such as affordability programs, digital navigation services, and digital literacy promotion.

States Should Not Label Locations as “Unserved” Based Solely on Their Covering Technology

In the challenge process outlined in Volume 1 of each Initial Proposal, states solicit public input on the accuracy of their list of locations deemed “unserved” or “underserved,” which are therefore eligible for BEAD networks.[11] Among other possible adjustments, states are given the option to automatically mark as underserved locations covered by certain older technologies such as Digital Subscriber Line (DSL). But coverage should be assessed by the performance of the connection, not the type of technology providing it. If DSL is largely incapable of reaching BEAD speeds, it will be excluded on the basis of those speeds in a properly conducted challenge process. Fixed wireless can offer speeds that often rival fixed broadband’s performance, but the reliability of its service is sometimes questionable, and some states similarly look to exclude it on that basis. A challenge process based on speed and performance metrics will highlight those areas where existing networks—regardless of technology—offer inadequate service. If reliability is a concern, states can and should conduct other checks—such as requiring evidence of a technology’s consistent performance over time—but they should not automatically write off entire technologies without investigating the quality of service they provide.

State Objectives Should Prioritize Coverage Reaching 100/20 Mbps Down/Up and a Range of Technologies

States’ stated objectives for the BEAD program often include what technologies and speeds they are allowing in the program. Per NTIA guidelines, BEAD networks must reach 100/20 Mbps at a minimum, and locations without access to those speeds are deemed “underserved.” States that go beyond that to push faster speeds, such as 100 Mbps symmetrical (both upload and download), or even 1,000 Mbps symmetrical, are preferencing faster speeds at the expense of other potential uses for BEAD funds. Similarly, states that plan to prioritize fiber networks or express reluctance to rely on technologies such as LEO satellites or fixed wireless where necessary are failing to use every tool available to them.

These priorities can also be gleaned from states’ proposals for their subgrantee selection processes. Indeed, Louisiana neatly sums up the challenge by asking, “What can Louisiana do to ensure that all eligible locations attract high-quality subgrant proposals that all can be funded within the total BEAD budget?”[12] States that mold their desired coverage to the amount of BEAD funding they have available, rather than the other way around, will see the best results and be most likely to have remaining funds for digital inclusion.

States’ Proposed Subgrantee Selection Processes Should Neither Preference nor Discourage Any Particular Provider Type

All providers—large nationwide ISPs, local rural providers, and municipal broadband alike—have an important and unique role to play in connecting the entire population. Though NTIA guidelines allow states to reject or preference certain providers (e.g., government-owned, or “municipal” broadband providers) as long as their preferences are expressed “neutrally and in advance,” states that choose this option are artificially limiting their universe of possible subgrantees and potentially discouraging strong contenders.[13] Conducted properly, the subgrantee selection process should welcome the widest possible range of applicants and guarantee a neutral assessment of their applications to select the strongest contenders, as long as each contender is playing by the same rules (regarding issues such as subsidies, taxes, poll attachments, etc.).[14]

States Should Set and Use the Extremely High Cost-per-Location Threshold in Such a Way That It Maximizes High-Quality Coverage, not Fiber Coverage

Though NTIA’s general mandate is to achieve universal coverage while maximizing fiber coverage, states have some room to impose their own priorities. For example, NTIA officially deems end-to-end fiber projects “priority” projects that automatically beat out “non-priority” applicants proposing to use other technologies, but states can either request waivers from NTIA to select more economical proposals in certain areas instead or set an extremely high cost-per-location threshold (EHCPLT) that limits fiber networks to where they are financially feasible. Most states plan to calculate their EHCPLT once the data from subgrantee applications is available and not before, but they should plan to arrive at a number that allows the most economical coverage with reliable and adequate technologies for their entire population. Furthermore, states should plan to stick to that threshold, and should not reserve the option to exceed the threshold in certain areas at their own discretion. The EHCPLT exists to help states determine where their overall broadband goals will be better served by using alternative technologies. Even a state that achieves universal coverage has not necessarily succeeded if it leaves no funds for inclusion activities, and the EHCPLT is an important tool to enable that.

States Should Create a Regulatory and Programmatic Environment That Fosters Efficiency

There is perhaps no greater potential area for wasted BEAD funds than in inefficient or outdated regulations that divert resources from broadband buildout. Disputes over access to critical infrastructure such as pole attachments can double the time and resources necessary to complete a broadband project. Before the BEAD program has really taken off, states have the chance to streamline this regulatory and programmatic environment to ensure as few resources as possible are spent overcoming barriers. NTIA already requires that states articulate how they plan to streamline regulatory barriers such as by adhering to dig-once policies, updating permitting processes for broadband builds, and ensuring access to critical infrastructure. The most successful states will both address all these potential issues and do so proactively, completing the majority of work before the brunt of the BEAD program takes place.

States Should Allow Area and Multiple Dwelling Unit Challenges to Streamline the Initial Challenge Process and Arrive at the Most Accurate Maps

Just as states are allowed to adjust their eligibility requirements based on technology, states can modify NTIA’s suggested challenge process to include both area and multiple dwelling unit (MDU) challenges.[15] Both types of modifications improve the efficiency of the challenge process by shifting the burden of proof based on what the evidence suggests, and states should allow both types of modifications for metrics such as network availability, speed, data caps, and technology. Area challenges, which are triggered when a certain number of challenges are submitted regarding a specific quality of a provider’s stated coverage (e.g., availability, latency, or speed) put the initial responsibility of proving the quality and extent of coverage on the challenged provider rather than the challenger.[16] Similarly, MDU challenges establish this burden of proof if a certain percentage of units within a single multi-dwelling unit challenge one of these metrics.[17]

None of this is about underestimating coverage or overstating gaps. ISPs that prove metrics such as the speed they provide on their end—even if, for example, a consumer’s device or Wi-Fi configuration leads them to experience slower speeds than that—can successfully defeat a challenge. Instead, proactively assigning the responsibility of proving coverage or lack of coverage based on broad patterns will streamline the entire process and help ensure the results are as accurate as possible. Since the least-served areas are often the most resource scarce and perhaps have the least institutional trust in and awareness of the BEAD program, sparing their representatives from that massive burden of proof will help avoid scenarios in which the least-served areas are also least able to advocate for themselves.

States Should Waive All Existing State Laws That Preference—or Disadvantage—Municipal Providers

Though this is a direct requirement of NTIA, it bears repeating: No particular type of provider should be preferred or prohibited from applying to the BEAD program.[18] This means states with existing laws that prohibit or impede municipalities that are interested in providing broadband should waive or adjust those laws. Similarly, of course, any regulations that offer asymmetric benefits to city-owned broadband should be waived, including their tax exempt status, preferential rights of way, or preferential government customer purchasing. A successful BEAD application process will be open to every realistic contender and then judge them on the merits on a truly level playing field. For example, municipal broadband that requires a large amount of initial funding (e.g., from local taxpayers), offers a less convincing business case than a private ISP does, or “cherry picks” the easiest-to-serve households should naturally lose out to the better private sector proposal. A regulatory environment that avoids slanting potential pools of applicants in one direction or another is an important first step.

States Should Take a Consistent, Proactive Approach to Readying Communities for Broadband Deployment

Streamlining likely regulatory barriers to BEAD implementation includes employing policies such as dig-once mandates, promoting the use of existing infrastructure, and improving permitting and access to infrastructure (e.g., pole attachments) and rights of way. NTIA simply requires that states indicate which barriers they have addressed and how they have done so. The strongest states should make every attempt to comprehensively address each of these potential barriers. Moreover, states should employ as consistent and proactive an approach as possible, both to ensure every community has an equal opportunity to attract ISPs and to minimize the amount of work that needs to be done—and BEAD funds that are spent—by subgrantees attempting to begin a project.

Many states have published and disseminated best practices for communities to adhere to.[19] Some states have gone further: Colorado’s broadband office, for example, employs a Broadband Ready Community Program designed to address the specific barriers found to be most prevalent in its state.[20] Communities that go through the steps of developing plans for BEAD funding and minimizing regulatory barriers to deployment are designated as “Broadband Ready Certified Communities” and preemptively signal their deployment readiness to ISPs. Indiana also has a Broadband Ready Community Program that lays out a set of concrete steps for communities to take, including making publicly available an inventory of public resources and local broadband data, streamlining permits and application processes, and appointing a main point of contact for all broadband deployment to ease communication.[21]

While a certification process is not the only way to success, states with designated programs that encourage communities to make themselves as attractive and available as possible will help shift some of the burden of BEAD implementation away from the core program and allow states to allocate BEAD funding with less need for padding to accommodate regulatory expenses. Of course, states must ensure that under-resourced communities are not penalized if they are unable to complete these types of certification programs without assistance, but the broad trend of encouraging proactive deployment readiness on the community’s side is a good one.

States Should Build Strong, Collaborative Structures to Govern Their Broadband Approach

Access to broadband and digital technologies is an enduring issue deserving of continuous oversight. The most successful states will view BEAD implementation not as a one-time project, but as an opportunity to design systems of governance for their broadband performance. Further, as the world becomes more digital, broadband access has an increasing effect on other areas of state concern such as the economy, education, healthcare, and general society. Ideally, states will build collaboration into their broadband governance structures to address that pervasiveness.

Nevada, for example, has for years now been establishing Broadband Action Teams (BATs) in each of its counties.[22] These BATs generally consist of a range of community leaders and delegates representing diverse interests. They also participate directly in the state broadband office’s BEAD planning process. As a final push to encourage ongoing local participation in its BEAD implementation, the Nevada broadband office is developing a public dashboard to track BEAD awards and then later the progress of the deployment projects.[23] Indiana’s broadband office takes a different approach by hiring a communication manager as an established position to directly meet communities where they are and help prepare them for the BEAD program’s implementation.[24] This will foster better communication between localities and the state broadband office and help ensure more accurate data flows, broader information dissemination, and ultimately a more data-driven approach to the state’s digital divide. Finally, Colorado’s emphasis on cross-agency collaboration led it to establish a Broadband Advisory Group dedicated to “supporting data collection efforts, policy, development, and conducting inventories of various initiatives and assets across agencies, all … related to infrastructure and digital equity.”[25] By housing various interests with unique perspectives and access to disparate information within the same group, the state aims to comprehensively address both deployment and equity concerns.

States Should Address Digital Inclusion Within BEAD

The value of funding BEAD deployment economically is that states can use their leftover funds for digital inclusion efforts. Just as the digital divide is driven by a host of interconnected reasons, including infrastructure gaps, affordability, and lack of access to technology or inability to use it, the most successful efforts to bridge that divide must address all of its major causes simultaneously.[26] Bolstering potential adoption rates—such as by providing affordability programs to consumers or increasing consumer interest in a broadband subscription—can help support an ISP’s business case to build a network. Long term, ISPs need consistent service uptake to be able to serve an area, and populations will only benefit if they can actually use and afford the networks that are built to their homes. Put another way, much of the digital divide needs to be solved with something other than or in addition to more deployment.

At NTIA’s last count, lack of interest in an Internet connection and affordability concerns explained over 75 percent of the offline population.[27] Under 4 percent of that population cited lack of infrastructure availability as their reason for remaining offline.[28] BEAD is the largest broadband funding program, and the entirety of the largest funding program should not be spent on a relatively smaller reason for digital exclusion simply because addressing that reason can be very expensive.[29] It is absolutely necessary to provide every resident of the United States with high-quality broadband as a first step toward universal connectivity, but current rates of coverage and the wide range of available technologies suggest that this should be possible for far less money than BEAD provides. The difference can be used to fund digital inclusion activities.

Even before arriving at their actual numbers for proposed deployment, states can signal their intentions to address inclusion concerns with BEAD by articulating plans for activities beyond deployment and prioritizing programs that address adoption and affordability concerns. Moreover, they can incorporate the spirit of digital inclusion into their BEAD programs by soliciting broad community input, accounting for the complexity of the digital divide, and following digital equity best practices such as relying on local implementation of programs wherever possible.

States Should Account for Community Impact in Their BEAD Subgrantee Selection Process

Communities, and institutions at their most local level, are often the most knowledgeable about the specific digital barriers they face and how they could best be addressed. Of course, it would be inefficient and likely unproductive for states to defer entirely to community preferences regarding subgrantee selection, but the suitability of a particular project for its intended population should be assessed to some degree.

One elegant solution that some states have suggested in their Initial Proposals is to include a subgrantee applicant’s evidence of community support as part of the applicant scoring process. Illinois’s subgrantee grading rubric, for example, awards applicants points “based on [the] degree of breadth and depth of community support for the project” including factors such as the number and diversity of community members expressing support for the project, the degree to which the proposal fits into any existing community plan, the extent to which it meets the community’s needs, and outreach conducted by the provider to gauge community interest.[30] West Virginia allows applicants to provide evidence of how a proposal will meet the needs of a particular community.[31] Many other states have implemented similar options in their rubric. Evidence that providers have engaged with the communities they propose to serve and further evidence that those communities are in support of a particular project will go a long way toward matching locations with the projects best suited to them. Of course, states must ensure that ideological preference such as simple aversion to big companies doesn’t dictate the choice of provider, but neutral community outreach and assessments such as community surveys can help ensure that a community with, for example, regular heavy rainfall is not relegated to a fixed wireless provider whose service would therefore be prone to outages.

States Should Articulate a Thoughtful Approach to Nondeployment Activities and Should Intend to Address Digital Inclusion Within BEAD

Every state is granted the opportunity to explain how it would spend leftover BEAD funds on nondeployment activities such as digital navigation services. Unfortunately, many states so far have declined to answer this question, and instead have stated that they do not anticipate having remaining funds after completing their deployment activities.[32] There are some notable exceptions: Virginia, for example, offers a detailed, thoughtful explanation of the range of nondeployment activities it will fund.[33] But laying out plans for nondeployment should be the rule, not the exception.

Many of the same states declining to fund nondeployment are proposing to spend extraneous funds prioritizing fiber and faster speeds when they would have funding left over if they viewed digital inclusion activities as an integral part of BEAD and economized on deployment funding accordingly. Even if a state will run out of funds with a cost-effective approach to BEAD deployment, it should still outline how it would allocate BEAD money for nondeployment activities and what those activities would be. First, any deployment project might go uncompleted, and unprepared states might be left floundering with unexpected additional funds and no predetermined use for them. Second, proposing nondeployment allocations upfront will allow community and NTIA input, as was granted for their deployment allocations. Third, articulating a plan for nondeployment spending upfront will also encourage states to think seriously about how to address digital inclusion within the context of the broader deployment approach.

States Should Show Evidence of Collaboration and Overlap Between Their BEAD and Digital Equity Plans

More than just building networks, at its core, the BEAD program is about building the infrastructural foundation for a more equitable, inclusive digital society. Building that into BEAD plans is about understanding the interconnected nature of digital inclusion and the need to intertwine deployment efforts and broader digital inclusion efforts wherever possible. With the BEAD and Digital Equity programs occurring in tandem, states that understand the digital divide’s multifaceted nature should show evidence of strong, continuous collaboration between staff members and working groups tasked with developing each plan. Colorado’s broadband office, for example, regularly engages with the state’s Digital Equity Committee, its Digital Equity Working Group, and its Digital Navigator program to ensure the BEAD plan adequately addresses equity concerns.

The best states go even further and embed digital equity procedures directly into their BEAD programs as well. Washington, for example, offers points in its actual BEAD subgrantee selection rubric to applicants that propose to offer adoption-enhancing programs or other digital navigation services in addition to broadband service.[34] This is an excellent method of prioritizing proposals that will have the greatest possible impact on the entire digital divide, not just the deployment aspect of it—and this type of approach is a means of ensuring that funds aren’t all spent on deployment upfront with none remaining for adoption.

States Should Ensure Accessibility and Implement Programs at the Most Local Levels to Maximize Diverse Participation

Successful BEAD implementation will need to harness diverse local voices to ensure that the particular needs of each state’s communities are met. There is a wealth of research on how to best ensure community participation and gain the trust necessary to get many offline communities online.[35] This research often suggests meeting people where they are, which can include traveling to their geographic locations and partnering with trusted community institutions to harness existing relationships.[36] States can even encourage local communities to implement BEAD-focused programs and events themselves using their intimate local knowledge of the community and broad community trust.

Many states are successfully accomplishing this already: Tennessee, for example, anticipates relying on a network of state universities, community colleges, and technical colleges to provide digital equity services and address residents’ needs.[37] It plans to employ their existing community relationships and on-the-ground knowledge in implementing its digital equity programs. Pennsylvania’s broadband office similarly emphasizes community input—and meeting people where they are—by cohosting regular community conversations on the BEAD program alongside local community-based institutions.[38] It further reduces barriers to participation by providing resources such as childcare and food at each event and by directly encouraging local communities to hold their own community conversations using resources and materials provided by the state office. Indiana, meanwhile, encourages its local communities to create their own broadband task forces to assess their own needs and individually collaborate with ISPs.[39]

Conclusion

Though there are some examples of particularly creative or effective approaches in states’ Initial Proposals, and some other areas where certain states need to adjust their approach, no one state is performing particularly strongly or particularly poorly in every area examined. (See the accompanying data visualization.) Nor is any state’s trajectory set in stone. Addressing broadband needs and successfully implementing the BEAD program is a complex, ongoing task that requires a thoughtful, collaborative approach and must be able to adjust when the broadband landscape, available resources, or even community needs change.

One critical resource available to every state right now is the publicly available Initial Proposal published by every single other state. In addition to investing sufficient time and resources into its own BEAD plan, each state receiving BEAD funding should keep an eye on other states’ BEAD and broadband plans as they emerge—particularly those hailed as standouts in some area—and look to them for inspiration. They should be ready to discard poor ideas, co-opt good ones, and constantly adjust their own plans based on community input and the success of their implementation. BEAD is meant to bring every U.S. resident online, and though states are each individually tasked with implementing their part of the program, that doesn’t mean they have to do it alone.

About the Author

Jessica Dine is a policy analyst focusing on broadband policy at ITIF. She holds a B.A. in economics and philosophy from Grinnell College.

About ITIF

The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) is an independent 501(c)(3) nonprofit, nonpartisan research and educational institute that has been recognized repeatedly as the world’s leading think tank for science and technology policy. Its mission is to formulate, evaluate, and promote policy solutions that accelerate innovation and boost productivity to spur growth, opportunity, and progress. For more information, visit itif.org/about.

Endnotes

[1]. “Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment (BEAD) Program,” BroadbandUSA: National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA), accessed February 2024, https://broadbandusa.ntia.doc.gov/taxonomy/term/158/broadband-equity-access-and-deployment-bead-program.

[2]. Masha Abarinova, “NTIA: 2024 will be ‘year of execution’ for BEAD,” Fierce Network, February 8, 2024, https://www.fierce-network.com/broadband/ntia-2024-will-be-year-execution-bead.

[3]. INTERNET FOR ALL, Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment (BEAD) Program Initial Proposal Guidance (Washington DC: NTIA, 2023), https://broadbandusa.ntia.doc.gov/sites/default/files/2023-07/BEAD_Initial_Proposal_Guidance_Volumes_I_II.pdf.

[4]. Ibid.

[5]. Ibid.

[6]. Internet For All, BEAD Initial Proposal Progress Dashboard, last updated April 16, 2024, https://www.internetforall.gov/bead-initial-proposal-progress-dashboard.

[7]. NTIA, Data Explorer: Internet Use Survey (Non-Use of the Internet at Home, updated October 2022), https://ntia.gov/other-publication/2022/digital-nation-data-explorer#sel=homeEverOnline&demo=&pc=prop&disp=chart.

[8]. “Digital Equity Act Programs,” BroadbandUSA: NTIA, accessed February 2024, https://broadbandusa.ntia.doc.gov/funding-programs/digital-equity-act-programs.

[9]. INTERNET FOR ALL, Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment (BEAD) Program: Reliable Broadband Service & Alternative Technologies Guidance (Washington DC: NTIA, January 2024), https://broadbandusa.ntia.doc.gov/sites/default/files/2024-01/BEAD_Reliable_Broadband_Service_Alternative_Technologies_Guidance.pdf.

[10]. Broadband Internet Technical Advisory Group (BITAG), “Overview of Broadband Technologies: A BROADBAND INTERNET TECHNICAL ADVISORY GROUP TECHNICAL WORKING GROUP REPORT” (January 2024), https://drive.google.com/file/d/19jnqQL73Y_VwcdcwKGgj71-8X507djHG/view.

[11]. Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment (BEAD) Program Initial Proposal Guidance (NTIA, 2023).

[12]. ConnectLA, BROADBAND EQUITY ACCESS AND DEPLOYMENT (BEAD) SUBGRANT PROGRAM DOCUMENTS (Office of Broadband Development and Connectivity), accessed February 2024, https://connect.la.gov/bead/.

[13]. Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment (BEAD) Program Initial Proposal Guidance (NTIA, 2023).

[14]. An exception to this rule is on Tribal lands, where states should defer to Tribes’ preference—if they express any—regarding the choice of provider.

[15]. Ibid.

[16]. Ibid.

[17]. Ibid.

[18]. Ibid.

[19]. See, for example, Wyoming Bead Program, Initial Proposal Volume II (Wyoming Business Council, January 2024), https://wyomingbusiness.org/broadband/bead/.

[20]. Broadband Equity, Access and Deployment (BEAD), Initial Proposal Volume 2 (Colorado Broadband Office), accessed February 2024, https://broadband.colorado.gov/funding/advance-BEAD.

[21]. Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment Program, “Connecting Indiana: Initial Proposal Vol 2” (Indiana Broadband), accessed February 2024, https://www.in.gov/indianabroadband/grants/bead/.

[22]. High-Speed NV, BEAD Initial Proposal Volume II (Nevada Governor's Office of Science, Innovation & Technology), accessed February 2024, https://osit.nv.gov/Broadband/BEAD/.

[23]. Ibid.

[24]. “Connecting Indiana: Initial Proposal Vol 2” (Indiana Broadband), accessed February 2024.

[25]. BEAD, Initial Proposal Volume 2 (Colorado Broadband Office), accessed February 2024.

[26]. Jessica Dine, “The Digital Inclusion Outlook: What It Looks Like and Where It’s Lacking” (ITIF, May 2023), https://itif.org/publications/2023/05/01/the-digital-inclusion-outlook-what-it-looks-like-and-where-its-lacking/.

[27]. NTIA, Data Explorer: Internet Use Survey (Non-Use of the Internet at Home, updated October 2022).

[28]. Ibid.

[29]. “Funding Programs,” BroadbandUSA: NTIA, accessed February 2024, https://broadbandusa.ntia.doc.gov/funding-programs.

[30]. Connect Illinois, Initial Proposal Volume 2: Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment (BEAD) (Illinois Department of Commerce & Economic Opportunity, December 2023), https://dceo.illinois.gov/connectillinois/federal-broadband.html.

[31]. West Virginia Office of Broadband, Initial Proposal Vol. 2 (West Virginia Department of Economic Development), accessed February 2024, https://internetforallwv.wv.gov/plans/.

[32]. See, for example, Broadband, Equity, Access, and Deployment Program (BEAD) Initial Proposal, Volume II (Arizona Commerce Authority, November 2023), https://www.azcommerce.com/broadband/arizona-broadband-equity-access-deployment-program/; also see Connecting Nebraska, Initial Proposal to the National Telecommunications and Information Agency (NTIA) Volume II (Nebraska Broadband Office), accessed February 2024, https://broadband.nebraska.gov/.

[33]. Commonwealth Connect: Broadband Equity, Access and Deployment Program, “Initial Proposal Volume 2” (Virginia Department of Housing and Community Development), accessed February 2024, https://www.dhcd.virginia.gov/bead.

[34]. Internet for All in Washington, DRAFT Initial Proposal Volume II (Washington State Department of Commerce), accessed March 2024, https://www.commerce.wa.gov/building-infrastructure/washington-statewide-broadband-act/internet-for-all-wa/.

[35]. Dine, “The Digital Inclusion Outlook.”

[36]. Ibid.

[37]. State Broadband Office, BEAD Initial Proposal: Volume 2 Draft (TN Department of Economic & Community Development), accessed March 2024, https://www.tn.gov/ecd/rural-development/broadband-office.html.

[38]. Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment (BEAD) Program, BROADBAND EQUITY, ACCESS, AND DEPLOYMENT INITIAL PROPOSAL VOLUME 2) (Pennsylvania Broadband Development Authority), accessed March 2024, https://www.broadband.pa.gov/funding/broadband-equity-access-and-deployment-bead-program/.

[39]. “Connecting Indiana: Initial Proposal Vol 2” (Indiana Broadband), accessed February 2024.

Editors’ Recommendations

July 8, 2024

Making Broadband Affordable, With Jake Varn

September 18, 2023