Technical and Legal Criteria for Assessing Cloud Trustworthiness

Global data and technology governance will be challenging without cooperation on cloud trustworthiness. Policymakers should avoid simplistic assessments based on nationality and instead develop more holistic assessments based on legal and technical criteria.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Key Takeaways

Contents

Trusted Cloud Is Critical to Global Data, Cybersecurity, and Technology Governance 6

Technical and Legal Criteria for Assessing Trusted—and Untrusted—Cloud Service Providers 15

Legal Criteria to Assess Geopolitical Risks and Cloud Trustworthiness 28

Introduction

Concerns about trusting cloud services have existed since their creation.[1] Growing geopolitical tension, coupled with the cloud’s pivotal roles in data privacy and cyber and national security, are prompting policymakers worldwide to address the numerous challenges posed by cloud services. However, many policymakers rely on misguided, knee-jerk assessments that equate local ownership with trustworthiness.[2] Focusing solely on a firm’s nationality without considering how a firm or its home country contributes to or detracts from cloud trustworthiness does little to enhance cloud cybersecurity and data privacy and create an open and competitive cloud market. Moreover, it undermines trade, cybersecurity, and national security cooperation between like-minded countries—such as G7 members (Canada, the European Union, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, the United States), Australia, Singapore, Japan, Korea, and India—by implying they distrust their trading partners’ cloud firms. While concerns regarding China’s control over its cloud and tech firms are growing, efforts to address the fundamental issue of cloud trustworthiness among the G7 and like-minded partners are lacking. Without collaborative efforts among like-minded countries to tackle the issue of cloud trustworthiness, establishing trusted data flows and governance will be challenging.

Policymakers have long been concerned about governments compelling cloud firms to surrender data for various purposes such as surveillance, law enforcement, and political suppression. Key initiatives aimed at addressing this issue include the European Union-United States Transatlantic Data Privacy Framework and its preceding agreements. Recently, policymakers have shifted their focus to the potential control exerted by foreign adversaries over the operational workloads provided by cloud firms to government and critical infrastructure sectors, particularly in the event of a major cyber incident or conflict. For example, U.S. cyber and national security officials are concerned that China could “flick the switch” to turn off or disrupt China-connected cloud and information technology (IT) services for both government and commercial services in the event of war.[3]

This points to an end scenario wherein the United States opts for technology sovereignty in pushing for a China-free ecosystem instead of adopting a risk-based approach that uses targeted mitigating actions to address the underlying issues, such as creating a secure environment to manage risks (e.g., well-managed updates, visibility and monitoring of network communications, pushing for equipment to use an open software stack so software can be interchangeable, etc.). China already pushes for a China-only technology system. The difference is that the United States and other like-minded countries greatly support, and benefit from, an open global digital economy. If the United States and everyone else pushes for their own technology system, everyone loses in terms of the negative impact it’ll have on trade, innovation, cybersecurity cooperation, and efforts to build trusted data and technology governance.

Getting the United States, the European Union, and other G7 countries, as well as other trade and security partners such as Australia, Korea, and India, to collaborate on cloud trustworthiness will be challenging due to problematic cloud policies. The United States is considering expanded data localization requirements as part of the Federal Risk and Authorization Management Program (FedRAMP) cloud cybersecurity certification system that federal government agencies use to procure cloud services. France and other EU member states also want data localization alongside other problematic “sovereignty requirements,” such as local ownership and control, as part of an EU cloud cybersecurity regime. Korea forces firms to use dedicated (not hybrid or public) cloud services that must store data locally and only use local staff, encryption algorithms, and equipment certifications. Australia set a precedent that even China hasn’t done in giving its signals intelligence agency (also a leading cybersecurity agency) step-in powers to assume control of cloud providers and the power to force firms to install software in certain situations, without giving firms clear avenues to seek an independent review of decisions or avenues for legal appeal. Similarly, the United Kingdom prevents firms from publicizing requests they’ve received for data or to take certain action and does not provide transparency reports about the number and types of requests it makes of firms. This restricted and opaque process is exactly what animates fears about China’s approach to accessing data.

Whether it’s in China, France, or the United States, data localization is a misguided policy—even in the case of government data and services. Localization does not improve data privacy or security.

The security of data depends primarily on the technical and physical controls used to protect it.

G7 and like-minded countries have laws, regulations, initiatives, and agreements that also provide a foundation for building a common approach to assessing cloud trustworthiness. Estonia is pushing for “trusted connectivity,” which is the goal to do business with partners according to common interests, democratic values, and high regulatory and social standards.[4] The United States, Germany, Australia, and 28 other countries have adopted the Prague Proposals on 5G, which are a set of technical and non-technical recommendations on risks when planning, building, launching, and operating 5G infrastructure around the world.[5] Elsewhere, the Common Criteria Recognition Arrangement (CCRA, involving over 31 countries) is one of the few globally recognized programs for mutual recognition (there are accredited labs in multiple countries) for evaluating the security of IT equipment and services.[6] Major cloud providers including Amazon, Google, Microsoft, SAP, and CISCO set out “Trusted Cloud Principles” on issues relating to data, going to customers to request data, cross-border data flows, and addressing conflicts in law.[7] The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s (OECD’s) member countries negotiated the Declaration on Government Access to Personal Data Held by Private Sector Entities (also known as the Trusted Government Access to Data Initiative) to improve trust in cross-border data flows by clarifying how national security and law enforcement agencies can access personal data under existing legal frameworks.[8] The Data Free Flow With Trust initiative, and its new secretariat at the OECD, provides a ready home for detailed discussions and research into how to build common approaches to trusted cloud.

Cloud trustworthiness assessments should involve both technical and legal criteria. Firms that use best-in-class technical controls and international technical standards, issue transparency reports about government requests for data, and cooperate with local cybersecurity agencies are demonstrating a variety of data points that positively define cloud trustworthiness. Likewise, whether countries have relevant data, cybersecurity, and privacy laws, regulations, and cloud cybersecurity practices and certifications are all data points to assess the behavior of a firm’s home government.

Cloud trustworthiness is not a purely technical issue, as political and security factors, such as the behavior of a firm’s home government, also define the security context that cloud firms operate in.[9] In particular, policymakers are concerned with China’s potentially broad, arbitrary, and opaque ability to access data and control its tech firms. However, policymakers should avoid mirroring China’s approach if they want to demonstrate that they’re different and better than China in regard to data privacy and security and to set the benchmark for what other countries around the world should aim for. Legal criteria to assess geopolitical risks should be specific and detailed. Policymakers can refer to international security, law enforcement, trade, and cybersecurity agreements as data points to demonstrate the trustworthiness of a cloud firm’s home government, for example, whether countries are party to relevant multilateral cyber and law enforcement agreements and initiatives, such as the Budapest Convention and the OECD Trusted Government Access to Data initiative. It’s also fair to assess a cloud firm’s relationship with its home government. For example, Germany’s Information Technology Law 2.0 assesses a nation’s potential control over cloud and whether it’s a part of a security defense agreement, namely, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).

G7, OECD, and other policymakers should establish a specific set of criteria for evaluating cloud trustworthiness rather than relying on vague national security and intelligence concerns, which often lack clarity and fail to address what firms and countries should do. This approach can be misused for protectionist purposes and other agendas. A positive and detailed list of criteria gives firms, and their host countries, a clear goal to work toward, as concerns about cloud trustworthiness are global and not just an issue for the EU, the United States, and China. Cooperation on cloud trustworthiness is much broader than just government procurement and critical infrastructure and raises significant economic, trade, and technology interests, as restrictive cloud measures can easily impact the broader digital economy.

G7, OECD, and other like-minded countries should establish specific positive and negative criteria to evaluate cloud trustworthiness rather than relying on vague national security and intelligence concerns.

This report begins by detailing why cooperation on trusted cloud is foundational to both cybersecurity best practices and technology’s growing role in foreign affairs, because if countries that trust each other in other contexts—such as defense, intelligence, law enforcement, and trade—don’t trust their respective cloud firms, how are they supposed to work together and with third countries on related issues, such as data governance and cybersecurity? The report then analyzes country case studies to highlight both constructive and problematic policies that are instructive when considering how like-minded countries should work together to develop criteria for cloud trustworthiness—and in doing so, hopefully lead countries to reconsider problematic policies. The report then analyzes a series of technical and legal criteria to consider when assessing cloud trustworthiness. This includes the use and development of new technical standards; mapping of technical controls, standards, audits, and cloud certification requirements; the critical issue of government access and operational control over data and cloud services; and cooperation with local cybersecurity authorities, among others.

A summary of the recommendations:

▪ Policymakers should use international technical standards to provide detailed and common definitions, concepts, use cases, and criteria to assess cloud trustworthiness and address issues associated with cloud cybersecurity, trust, and risk.

▪ Policymakers should conduct a mapping exercise across cloud cybersecurity regimes to identify and use common technical controls and standards. This would allow discussions about how to build alignment and interoperability, and ideally mutual recognition, between different systems so that firms that undergo an audit in one country can use this to demonstrate compliance in other countries. This would reduce regulatory compliance and improve cloud cybersecurity and competition in cloud markets.

▪ Governments from like-minded countries should assess whether a country has an independent judiciary and rule-of-law regime to assess the risks of domestic and extraterritorial government access to data held by cloud firms. Combined with an assessment of a country’s privacy, cybersecurity, and surveillance laws, this provides a holistic picture as to whether there are constraints on government powers in relation to government access to data held by cloud firms.

▪ Cloud firm and government transparency and openness in and around government requests for data builds trust. Policymakers should set the right example in ensuring that national security and other laws don’t prevent firms from reporting government requests for data. Policymakers should work with cloud firms to develop a common template for transparency reports they provide on the number and types of requests and their response to government requests for data around the world.

▪ Policymakers should use international security, defense, data privacy, law enforcement, and cybersecurity agreements as positive legal and geopolitical criteria to assess whether a cloud provider’s home country should be considered trusted. These agreements address the central concern about how governments behave in relation to cloud services and provide clear evidence about the compliance of legal norms, principles, and customs by which a cloud supplier is legally bound.

▪ Policymakers should develop common criteria, and improved transparency, to determine whether there is clear and demonstratable legal and operational separation or interdependence between a firm and its home country government.

▪ Policymakers should consider cooperation with local cybersecurity authorities as a demonstrated feature of trusted cloud firms. Likewise, whether countries have constructive and meaningful cybersecurity cooperation and agreements should be a consideration for assessing whether a cloud firm’s home country can be trusted vis-à-vis their home cloud firms.

▪ G7 countries should create a dedicated workstream on trusted cloud criteria as part of the newly established OECD-based secretariat for the Data Free Flow With Trust initiative.

Trusted Cloud Is Critical to Global Data, Cybersecurity, and Technology Governance

The cloud plays a crucial role in the global digital economy, impacting broader concerns such as trusted data flows, governance, and digital trade. Cloud trustworthiness becomes increasingly significant amid geopolitical tensions and the migration of critical infrastructure sectors to the cloud. It will only grow more contentious, for example, as countries consider extending lawful intercept requirements beyond traditional telecommunication services to cloud services and enact new laws and regulations that target the cloud as part of updated intelligence and national security laws.[10]

Global cybersecurity cooperation relies on public-private collaboration and information sharing. This will only be made more difficult than it already is—given existing cloud market access and data transfer restrictions in countries—if countries use broad and vague concerns about trustworthiness as another tool to target cloud firms.[11] Cloud firms need market access and data transfers to seamlessly map global threat patterns against domestic ones or trace signs of malicious activity from global networks onto domestic ones.[12]Likewise, public-private incident analysis and responses will be made more difficult, if not impossible, if cloud firms from trusted partners are excluded from a country’s market.

Restrictions on cloud providers from otherwise trusted partners undermine the cloud’s increasing significance in foreign, technology, and economic policy. It’s contradictory for countries to trust each other with national defense while distrusting each other’s cloud firms. How can G7 and like-minded countries cooperate on data privacy, cybersecurity, and other issues if they lack trust in each other’s cloud providers, especially in global and third-country engagements? Whether in the U.S.-EU, EU/U.S.-Africa, or other bilateral and regional contexts, mutual trust is essential for collaboration on global digital and cyber issues. For instance, while the United States and EU aim to engage third-country governments on trusted ICT infrastructure, France’s (and potentially the EU’s) cloud cybersecurity regulations may not trust U.S. cloud firms. Collaboration on cloud trustworthiness is crucial for United States, EU, and other partners in trade and security efforts to establish global data and digital governance and deter malicious actors in cyberspace.[13]

It’s contradictory for countries to trust each other with national defense while distrusting each other’s cloud firms. Restrictions on cloud providers from otherwise trusted partners undermine their ability to build trusted data, technology, and digital trade governance.

Getting cloud cybersecurity and trust frameworks wrong also entails significant economic costs. The European Center for International Political Economy estimates that discriminatory data localization and nationality requirements (so called “sovereignty” requirements) in the

European Cybersecurity Certification Scheme for Cloud Services would lead to estimated

losses for EU member economies in annual gross domestic product (GDP) from $31 billion to $659 billion within two years of implementation, depending on the extent of restrictions.[14]

While cloud trustworthiness is just one of several rationales China uses to restrict U.S. firms

from accessing its cloud market, the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) conservatively estimates (based on market-share comparisons) that Amazon’s and Microsoft’s cloud services (delivered as Infrastructure as a Service, or IaaS, which is restricted in China)

lost a combined $1.6 billion in forgone revenue over the two-year period from 2017 to 2018.[15] While U.S. firms may never get the same fair and equal market access as Chinese firms get in the United States, the estimate is indicative of the economic impact if other countries are allowed to use broad and opaque concerns about cybersecurity and nationality to simply block access to their cloud markets.

Country Case Studies

China is not alone in using broad and vague cybersecurity requirements as cover to discriminate against foreign firms due to their nationality.[16] These case studies include both problematic and constructive policies from countries that are interested and engaged in efforts to build trusted IT infrastructure and governance, such as with the cloud. Some case studies focus on trustworthiness policies related to the use of 5G. The case studies are instructive in considering positive and negative criteria to define trusted and untrusted cloud services.

Australia’s Critical Infrastructure Act and How One Problematic Firm Shaped It

Cyberattacks on critical infrastructure are a recurring issue in Australia, mirroring global trends. The Australian Cyber Security Centre reported that one-quarter of reported cyber incidents in 2020 and 2021 were associated with Australia’s critical infrastructure or essential services.[17] A specific cybersecurity situation also had a major impact on the law. The Australian’s governments response—the Security Legislation Amendment (Critical Infrastructure Protection) Act 2022 (SLACIP Act)—includes both problematic and commendable policies that are useful when developing a comprehensive approach to assessing cloud trustworthiness.[18]

Australia’s SLACIP Act does some things well. It aligns certain key definitions of critical infrastructure with those used by the EU and the United States. It requires firms that are subject to the legislation to provide annual reports to the government regarding their risk management programs. It also provides powers to government agencies with cybersecurity capabilities, such as the Australian Signals Directorate (ASD, Australia’s signals intelligence agency, which is also responsible for information security), to help firms (which often lack either the capacity or specific capabilities) to respond to major cyber incidents.

No other country, including China, has coercive and emergency step-in powers like those of Australia’s SLACIP Act, which allows the government to compel a firm to install software on corporate systems and for (as a last resort) Australia’s Signals Directorate to step in and control a firm.

However, the SLACIP Act has also created coercive requirements and emergency step-in powers that are broad and unprecedented—no other country, including China, has done what Australia has done with the SLACIP Act. The new powers are rife with the potential for unintended consequences, as China and others could easily copy and misuse these powers to control local cloud providers and their data and services.[19]

The SLACIP Act allows the government to compel a firm to install software on corporate systems that are deemed to be of national significance. However, the legislation does not provide broad enough protections to companies subject to this power from any damages or legal liability arising from the compelled installation of software. The legislation lacks critical safeguards and limitations, such as allowing firms to seek judicial redress or receive an independent review of the security, technical feasibility, and necessity of the software to be installed. The legislation creates transparency and reporting requirements on firms subject to the legislation, which is generally fine, but it does not reciprocate by requiring the government to report on how it uses

its new powers.

The SLACIP Act’s strongest, and most problematic, powers allow ASD to step in and control a firm subject to the legislation, including cloud services. This is meant to be a measure of “last resort” in circumstances where a cybersecurity incident has, is, or is likely to impact a critical infrastructure asset and therefore Australia’s national interest. There is little administrative oversight of this extraordinary power, such as allowing an independent technical expert to advise on the appropriateness (or technical functionality) of the government using these powers. The lack of oversight creates security, compliance, and legal liability concerns for cloud providers by introducing potential vulnerabilities into a cloud service provider’s system. The lack of independent review or legal redress for firms to challenge orders compounds concerns about the law and the precedent it sets.[20]

ASD’s Director-General Rachel Noble detailed, without naming names, a real-world example that prompted these changes. This firm’s network was assessed as being of national importance and experienced a service outage due to a cyber incident. Despite the national impact, the firm refused to cooperate with local authorities, including ASD. Three months after the initial network outage, its network was taken down again. Somewhat mitigating this example, Ms. Noble highlighted that firms could avoid direct intervention by the Australian government under these powers if they did what’s “right and reasonable” in terms of high-level cybersecurity and cooperate and share information with the government.[21]

Direct government control over cloud services represents a dramatic step that raises major cybersecurity and data privacy concerns. Governments likely lack the technical expertise to effectively manage such systems, raising legal liability concerns regarding their advice and actions. While non-responsive cloud firms should face severe consequences, this underscores the importance of considering factors in assessing a cloud firm’s trustworthiness before enacting legislation for extreme scenarios. Australia’s new critical infrastructure law addresses some aspects of this issue but fails to offer alternative remedies for cloud service providers facing cybersecurity events before resorting to extreme measures.

Costa Rica’s Trusted Supplier Decree Uses the Budapest Convention as a Criterion to Assess 5G Trustworthiness

In September 2023, Costa Rica’s president signed a trusted supplier decree that requires information communication technology (ICT) providers interested in building its 5G network to be from countries that have adopted the principles of the Budapest Convention on Cybercrime.[22] The decree effectively bars Chinese ICT firms such as Huawei from developing the country’s 5G networks.[23] The United States plans to hold a regional conference on protecting 5G networks in April 2024 to build upon Costa Rica’s approach.[24]

Costa Rica’s use of the Budapest Convention as a criterion for trustworthiness is noteworthy. This convention is among the few international agreements that demonstrate a country’s commitment to collaborating with others on cross-border law enforcement cooperation and access to data for criminal investigations. Given the global nature of crime, law enforcement requires new tools to work effectively with partners. The Budapest Convention is the first multinational treaty aimed at combating Internet and computer crime by harmonizing national laws, improving investigative techniques, and enhancing cooperation among nations. As of 2024, 69 countries are parties to the Budapest Convention, while another 22 have signed on or been invited to join.[25] The convention facilitates the use of procedural powers and tools for international cooperation concerning electronic evidence for various offenses, including botnets, phishing, terrorism, identity theft, malware, spam, distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks, critical infrastructure attacks, election interference, and cyberviolence. Its Second Additional Protocol further enhances international cooperation between law enforcement and judicial authorities, cooperation between authorities and service providers in other countries, conditions and safeguards for access to information by authorities in other countries, and other safeguards, including data protection requirements.

Costa Rica’s use of the Budapest Convention as a criterion for trustworthiness is noteworthy, as it is among the few international agreements that demonstrate a country’s commitment to collaborating with others on cross-border law enforcement cooperation.

The Czech Republic Uses EU and NATO Membership, Plus Other Criteria, to Assess 5G Trustworthiness

The Czech Republic’s criteria for assessing the trustworthiness of 5G technology suppliers includes strategic criteria, such as whether the supplier and controlling entities are based in the EU or a NATO country; the firm is based in a state that is a member of international agreements on cybersecurity, such as the Budapest Convention on Cybercrime; it has an agreement with the EU on data privacy or cybersecurity, such as the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) or an agreement with the Czech Republic on the exchange and mutual protection of classified information; or is a party to the World Trade Organization’s (WTO’s) Government Procurement Agreement. It also includes the criteria that firms are willing to commit to, by means of a statement, declaring that they are legally able to refuse to disclose confidential information from or about customers to third parties.[26]

The European Union’s Cloud Cybersecurity Regime and Its Sovereignty Requirements

The European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA) is developing a European Cybersecurity Certification Scheme for Cloud Services (EUCS).[27] EUCS is similar to what FedRAMP does for the U.S. federal government: it provides a harmonized approach to cloud cybersecurity certifications to both ensure a better overall level of protection and reduce the cost and complexity for firms and government agencies contracting cloud services. However, unlike FedRAMP, France and other EU member states advocate for discriminatory EUCS requirements that make local firm ownership and control—rather than the use of best-in-class cybersecurity practices—the defining factors in ascertaining whether a cloud service provider can be deemed trusted and allowed to operate in the EU market.[28]

Initial EUCS proposals also included data localization (again, similar to France’s cloud certification scheme). Whether it’s in China, France, or the United States, data localization is a misguided policy—even in the case of government data and services. Localization does not improve data privacy or security.[29] The security of data does not depend on where it is stored. Organizations cannot escape complying with a nation’s laws by transferring data abroad. As a result, data localization is not necessary to force an organization to comply with domestic data laws. The security of data depends primarily on the technical and physical controls used to protect it, such as strong encryption on devices and perimeter security for data centers.

For example, the hack of the U.S. Office of Management and Budget—one of the most notorious hacks, given the U.S. government data involved—occurred against data services on premises in U.S. government agencies.[30] Policymakers misunderstand that the confidentiality of data does not generally depend on which country the information is stored in, but rather only on the measures used to store it securely. A secure server in Malaysia is no different from a secure server in the United Kingdom. Data security depends on the technical, physical, and administrative controls implemented by the service provider, which can be strong or weak, regardless of where the data is stored.

France and other EU member states advocate for discriminatory EU cloud cybersecurity scheme requirements that make local firm ownership and control—rather than the use of best-in-class cybersecurity practices—the defining factors in assessing whether to trust a cloud service provider.

Thankfully, some EU members (namely, the “D9+” group of EU member countries: Belgium, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Ireland, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Spain, the Czech Republic, and Sweden) raised specific concerns and issues about these problematic sovereignty requirements and forced changes to the EUCS proposal.[31] In February 2024, the European Commission stated that the EUCS would not include ownership conditions, but rather propose control requirements—and that ENISA has based its draft on global standards and taken inspiration from approaches adopted by EU’s trading partners (namely, the U.S. FedRAMP).[32]

While a positive step, there remains the potential for the EUCS to introduce discriminatory and restrictive requirements with significant market implications. It’s plausible that the EUCS might still permit EU member states to impose highly restrictive and discriminatory requirements for high-risk/impact levels, such as government services, and allow them to use a firm’s certification at this level as a requirement in other laws, regulations, and sectors. This would mean that restrictions that were initially highly targeted to only certain government services would extend the broader commercial market. This same spillover is now happening in Korea.

France’s Discriminatory Cloud “Sovereignty” Requirements

Taking a page out of China’s playbook, France enacted a discriminatory “sovereignty” cloud cybersecurity regime (known as SecNumCloud) that defines “trusted” as locally owned and controlled cloud firms, along with data localization and also local staff and board requirements.[33] These requirements preclude foreign firms from providing cloud services to the government and the over 600 firms that provide “vital” and “essential” services.

Launched in 2016, as of 2021, only four companies, all French, have been certified as trusted. SecNumCloud’s discriminatory restrictions have no legal basis in European privacy or cybersecurity law in that the EU’s GDPR has its various requirements, but SecNumCloud’s explicit data localization, local staff requirements, and ownership and board caps aren’t reflected elsewhere.[34]

Germany’s Information Security Law Uses Several Non-technical Criteria to Assess Trustworthiness

In May 2023, Germany enacted its new “IT Security Act 2.0,” which includes several useful provisions to define technical and non-technical criteria for assessing the trustworthiness of cloud and IT firms. Germany’s trustworthiness indicators are interesting for using specific security, defense, and trade agreements, such as EU and NATO membership, as critical data points. Along the same lines, Denmark enacted telecommunications legislation in 2021 that gives its intelligence officials the ability to block any domestic telecom deal involving suppliers from countries Denmark doesn’t have a security agreement with, which excludes all except Sweden (for Ericsson) and Finland (for Nokia).[35]

Firms must provide a guaranteed declaration to demonstrate that their products do not have features that could be exploited for malicious purposes. Firms also need to send reports to the government about the cybersecurity certifications, audits, and technical measures they’ve enacted in the previous two years. The government can provide guidance and feedback to firms on organizational and technical precautions based on their reporting.

Germany’s new “IT Security Act 2.0” includes criteria about whether a cloud firm is from a NATO member country, is controlled by a government, and that government has been or is involved in activities that undermine German and EU public order and security.

The law applies to critical infrastructure operators and includes special requirements for digital service providers, such as incident reporting requirements. The government can prohibit operators from providing services if they fail these trustworthiness indicators, as they could compromise public order and security. Article 9b of the IT Security Act 2.0 sets out the following indicators for assessing external contextual risks that contribute to cloud and IT trustworthiness:

▪ The manufacturer is directly or indirectly controlled by a government, including other government agencies or armed forces, of a third country.

▪ The manufacturer has already been or is involved in activities that have had an adverse effect on the public order or security of Germany or another member state of the EU, the European Free Trade Association, or NATO, or on their facilities.

▪ The use of the critical component is consistent with the security policy objectives of Germany, the EU, or NATO.

India’s Evolving Cloud Cybersecurity Certification Scheme and Its Efforts to Target Chinese Hardware, Software, and Data

India’s emerging cloud cybersecurity regime includes both good and bad elements. India’s approach is important, as it is one of the fastest growing public cloud markets in the Indo-Pacific region. The government and private sector have been working to adopt and use cloud, such as through the government’s “GI Cloud” (also known as “Meghraj.”)[36] However, India often uses unspecified concerns and vague criteria regarding trust as part of its cloud and IT supply chain and import regime. China is the target of many restrictions, but it also often discriminates against firms and products from other countries, in part to favor local firms and force them to set up local operations in India.

India’s evolving approach to “trust” covers both goods and services critical to the digital economy. India’s approaches to trust and cloud vary by sector and agency; some include discriminatory requirements such as data localization, while others don’t.[37] The Securities and Exchange Board of India hasits own, sometimes conflicting, cloud regulations.[38] The Reserve Bank of India issued guidance on the outsourcing of IT services (including cloud computing services) and also includes technical controls and risk management strategies firms must adopt.[39] In June 2023, India enacted mandatory testing and certification of telecommunication products using India-specific standards and tests (instead of international ones), including for 5G base stations, 5G core products, and hypervisor equipment.[40] In October 2023, India asked ICT hardware firms to provide international certifications to demonstrate that their products are from a “trusted” source (without specifying what those are) before allowing license-free importing of them.[41]

India’s Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology manages the program to certify and audit cloud services used by the government. Firms must use a prescribed list of security, storage, and interoperability criteria and technical standards and cooperate and share information with local cybersecurity agencies, such as CERT-India.[42] India uses a government-operated audit agency—the Standardisation Testing and Quality Certification (STQC) Directorate—to certify data centers and cloud providers.[43] The STQC is a signatory to the CCRA for evaluation and certification of IT products for security, which means products that receive certification from the STQC can be accepted in other member states without the need for re-certification.[44]

While India’s approach to auditing and certifying cloud providers for government and commercial use shares similarities to other countries, it still includes opaque and discriminatory elements that fail to specify why certain cloud firms are trusted while others are not. At its highest level, India’s Government Community Cloud requires the creation of dedicated cloud infrastructure to offer services to central, state, and local government agencies and state-owned enterprises and banks. U.S. and Japanese cloud firms are certified and authorized to provide a variety of cloud services to Indian government clients, but not for the Government Community Cloud.[45]

Korea’s Unprecedented Public Sector Cloud Restrictions

Korea’s security certification for public sector cloud service procurement, known as the Cloud Security Assurance Program (CSAP), includes several highly restrictive requirements.[46] Because Korean cloud firms have built their systems in Korea using local data centers and personnel, these requirements pose no undue burden to local suppliers. They do, however, constitute a form of discrimination against foreign suppliers, as not a single foreign cloud provider has been certified, even at CSAP’s “low risk” level.[47]

Korea’s CSAP is unprecedented among developed countries as it does not allow firms to use a “multi-tenant” architecture for data centers so that they can use the same data center (but use technical controls to establish technical, as opposed to physical, separation of data) to provide services to both commercial and public sector customers. Korea’s National Intelligence Service must certify all equipment used in CSAP (instead of using international cybersecurity certifications, such as the Common Criteria program) and local encryption algorithms (Korea’s local encryption algorithm, known as ARIA, is not used by anyone outside of Korea).[48] Cloud providers must store all data in Korea and only use equipment, resources, and personnel located in the country. Not only that, but a recent proposed amendment would extend these restrictions to mid- and high-risk data.

CSAP’s discriminatory and restrictive requirements act a technical barrier to trade and undermine cybersecurity, as it forces firms to adjust from their global best-in-class approach to cybersecurity to account for Korean operations (if they have any). Korea’s restrictive and discriminatory approach to cloud governance is growing. For example, the Ministry of Health and Welfare’s recently included CSAP-like controls—such as the physical location of cloud facilities, data residency, and cloud cybersecurity certification obligations—as a requirement for electronic medical record system providers who seek to use public cloud services.[49]

Romania Uses Strategic Partnerships as Criteria to Assess 5G Trustworthiness

In 2019, the United States and Romania signed a memorandum of understanding that agreed on the threats posed by untrusted 5G vendors as part of a risk-based security approach, including a “careful and complete evaluation of 5G vendors.”[50] In 2021, Romania enacted a new 5G law that says a vendor’s evaluation should state whether a company is subject to control by a foreign government, has a transparent ownership structure, and is subject to a legal regime that enforces transparent corporate practices.[51] The 5G Law was criticized for a lack of technical criteria and a failure to observe the provisions of the EU’s own 5G toolbox.[52] Applications are considered by Romania’s Supreme Council of National Defense (CSAT), which takes into account Romania’s international legal commitments and strategic partnerships, including its memorandum on 5G with the United States.[53]

The United Kingdom’s Investigatory Powers Act Undermines Cloud Trustworthiness

The United Kingdom’s Investigatory Powers Act (IPA) undermines good practices and principles involving cloud firms and government requests for data and cloud firms’ efforts to use best-in-class cybersecurity tools, such as encryption and not creating “back doors” to give governments preferential access to their data. The IPA’s attack on good cybersecurity tools and measures runs counter to prior U.K. government policy and the U.K.’s National Cyber Strategy to be perceived as a “leading responsible and democratic cyber power.”[54]

United Kingdom’s IPA undermines cloud firms’ efforts to use best-in-class cybersecurity tools, such as encryption and not forcing firms to create “back doors” for government access. The IPA also lacks transparency and reporting requirements around requests for data.

Cloud service providers are subject to the IPA, and thus, the government can serve warrants on cloud firms to provide enterprise customer data.[55] The IPA is extra-territorial in that it captures firms who may not be based in the United Kingdom. The IPA also requires firms to notify the Secretary of State in advance of making any technical or other relevant changes, and to maintain the status quo or “freeze” their products ’capabilities (such as for improved cybersecurity and privacy) while a review of an IPA notice is pending.[56] While the IPA includes some legal safeguards (such as a review process by judicial commissioners and the Investigatory Powers Commissioner), it does not include transparency and reporting provisions that allow firms to publicize the requests made to them or for the public to see how many, and what type, of requests the government submits to firms.[57]

The U.K. IPA’s attacks on encryption and good cybersecurity practices go to the heart of concerns about cloud trustworthiness, as they are the same policies, including the lack of openness and transparency, that underpin concerns about China and the policies it uses to access data held by firms.

The United States’ Problematic Clean Network and Cloud Initiatives and Proposed Expansion of Data Localization in FedRAMP

The United States’ long-standing defense of a free and open Internet, and opposition to data localization and measures that discriminate against foreign digital products and firms, is in question following a series of policy changes made across both the Trump and Biden administrations.

In August 2020, the Trump administration expanded the “Clean Network” initiative to include “Clean Cloud” to address data privacy, security, and human rights concerns related to China and other authoritarian governments and non-state actors. The Clean Cloud component focused on preventing sensitive U.S. personal information and intellectual property from being stored and processed on cloud-based systems accessible to foreign adversaries, namely, China, without using any clear and detailed criteria.[58] The initiative was based on a simplistic focus on nationality, and, ultimately, did not lead to substantive changes in U.S. policy. It was a model for the type of protectionist policies the United States has traditionally opposed in China and elsewhere given that it focused on nationality and lacked any risk-based criteria.[59]

In 2023, U.S. digital policy saw a significant shift when the United States Trade Representative (USTR) Katherine Tai withdrew from negotiations on data flows and digital trade at the WTO. Other U.S. government agencies did not support the change, as it would have undermined their efforts to build a free and open Internet and digital economy. The controversial USTR decision remains in place and the Biden administration has not revised or clarified its approach to supporting digital trade and an open Internet.

Also in 2023,the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) released a proposal that would greatly expand the use of data localization within the U.S. government program (FedRAMP) that certifies cloud services used by U.S. federal government agencies. At the moment, data localization is only a minor part of FedRAMP (individual U.S. government agencies can require it as part of their cloud contracts). The DOD proposal would require data localization for all cloud computing services at the FedRAMP “high-impact” level.[60] High-impact risks include sensitive (but unclassified) federal information such as law enforcement, emergency services, and health care data, so breaches to government systems containing this data would be highly damaging. In 2017, DOD accounted for 33 percent of high-baseline use in the U.S. government, followed by the departments of Veterans Affairs (16 percent), Homeland Security (13 percent), and Justice (10 percent).[61]

Technical and Legal Criteria for Assessing Trusted—and Untrusted—Cloud Service Providers

Policymakers from like-minded countries need to develop technical and legal criteria to use as part of a holistic assessment about the trustworthiness—or lack thereof—of cloud providers. They need to avoid simplistic, and ultimately unhelpful, assessments based on nationality. Technical and other demonstratable criteria serve as more visible elements of cloud trustworthiness, but they do not address other less-visible (i.e., geopolitical) elements related to a cloud firm’s home government’s approach to data security and privacy, including their access, use, and control over cloud services and data.

Policymakers should use a flexible and risk-based approach to assess and address concerns about cloud trustworthiness—one that reflects the fact that both risk and trust depend on context in terms of the sector, data, and products used and the countries involved. It also provides policymakers with flexibility to tailor mitigating measures to cloud firms based on their individual situation. Flexibility and adaptability are crucial, as the context and data points about a firm’s trustworthiness can change and thus alter the cybersecurity risks involved. Policymakers should use a comprehensive set of criteria to assess, individually and in aggregate, the elements that contribute to a cloud provider’s risk profile and the set of threats for a given application. The goal should not be to apply an exhaustive and prescriptive list to each and every cloud firm and its home country, but rather to provide a diverse set of tools that allow policymakers to identify and address specific risks. A flexible and risk-based approach allows policymakers to differentiate between high-risk strategic operations (e.g., government services and critical infrastructure) while allowing other regulatory tools and agencies to oversee cloud-related cybersecurity risks in less-sensitive areas.

In contrast, policymakers in China, France, and elsewhere pursue protectionist digital and tech “sovereignty” strategies that are based on simplistic assessments of nationality, as they believe doing so addresses concerns around government access to cloud data and services. This is misguided, as it may allow high-risk cloud services from a firm based in a friendly nation and deny low-risk cloud services from one perceived as less friendly. Policymakers should instead be considering overall net risk for cloud services. Using simplistic heuristics is not only misguided, but counterproductive, in that they undermine cloud services and fail to address underlying issues around government access to data, data privacy, and cybersecurity.

The following sections detail a nonexhaustive list of technical and nontechnical criteria policymakers should use to assess cloud trustworthiness.

International Standards Are Foundational to Cloud Cybersecurity and Trustworthiness

International standards provide common technical specifications for like-minded countries to use, which, when put together across various related issues such as risk, cybersecurity, and privacy, offers a demonstratable foundation for trusted cloud services.

Standards provide a common set of detailed and structured instructions on how to achieve a certain technical requirement. Policymakers should use international standards to assess cloud trustworthiness, as they provide common definitions, concepts, use cases, and criteria to assess associated issues such as cybersecurity, trust, and risk. This avoids the situation wherein regulators in different countries talk about different things when focusing on trustworthiness, cybersecurity, and risk. Standards also provide common, defined criteria to assess cybersecurity and risk, and thereby provide a standardized approach to assessing each of these issues; using different criteria would lead to different results. Most cloud firms publicly report the many and varied standards (and certifications) they as a result of operating across multiple countries.[62]

International standards, such as those from the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC), represent best practices, as they are developed by technical experts as part of an open, technocratic, and consensus-based process. The governance principles that govern standards bodies ensure that no one firm or stakeholder can dominate the process or outcome.[63] This is important, as it ensures firms do not have to use country-specific standards, such as those in China, which has developed standards in an opaque, closed, and non-consensus-based process. These types of country-specific standards lead to outcomes that are not best (technical) practice, as they can be misused for industrial policy, protectionist, or political purposes.

Cloud computing is based on high levels of standardization for hardware and software and the services built on these products. Combining the high standardization of cloud computing with a high standardization of information security and ongoing work on cloud trustworthiness standards provides a path forward to developing a broad set of tools to assess cloud trustworthiness.[64] For example, ISO/IEC standard 27001 is the world’s best-known standard for information security management systems.[65] ISO/IEC standard 27017 on information security controls for cloud services is also very common.[66]

International standards provide common technical criteria for policymakers and firms in like-minded countries, which, when put together across various related issues such as risk, cybersecurity, and privacy, offers a demonstratable foundation for trusted cloud services.

Existing international standards already define trustworthiness as the “ability to meet stakeholders’ expectations in a verifiable way.”[67] However, what this means in practice depends on the context or sector and the product, service, data, technology, and process used. Characteristics of trustworthiness include accountability, accuracy, authenticity, availability, controllability, integrity, privacy, quality, reliability, resilience, robustness, safety, security, transparency, and usability.[68] There are existing or new standards that relate to all these technical features.

Technical standards concerning risk are central to addressing concerns about trust. International standards provide specific definitions and indicators of potential external contextual risk.[69] Risk is usually expressed in terms of risk sources (including those related to all relevant stakeholders), potential events, their consequences, and their likelihood.[70] Uncertainty is the root source of risk. This clearly applies to trusted clouds and the data and workloads they manage in terms of the “deficiency of information” that matters in how a service is provided, which could include a government’s opaque control over its cloud companies.

The challenge for policymakers is identifying existing and emerging standards that, together, build a strong technical foundation for cloud trustworthiness. The goal for policymakers should be to integrate ISO/IEC risk assessment and other technical standards into their cloud certification schemes so that they specifically target trust concerns around cloud providers.

This has happened in the telecommunications sector. For example, the Telecommunications Industry Association’s Supply Chain Security Management System (SCS 9001) standard is a voluntary, industry-led, process-based standard that operationalizes several well-known industry best practices and guidelines, such as the Prague Proposals for 5G (which deals with trustworthiness as well).[71]

Policymakers from like-minded countries need to track and support—and where necessary engage—with ISO, IEC, and industry-led standardization efforts to develop new technical standards related to cloud trustworthiness. In September 2023, a new ISO/IEC project (ISO/IEC NP 11034) started to develop a new specific standard for trustworthiness in cloud computing.[72] If policymakers want standards to address their concerns, they should track what’s happening and, where necessary, engage with the stakeholders developing the standard to ensure they develop one that addresses their policy concerns.

International standards, which are used by most major cloud providers in the United States, Europe, and Asia, are an essential, but not sufficient, tool to assess cloud trustworthiness. Many Chinese cloud providers also use international standards. This points toward the importance of a holistic assessment and the use of a diverse set of technical and non-technical criteria to assess cloud trustworthiness. This does not detract from the role and value of standards. Technical standards can address many, but not all, of the more difficult aspects of assessing cloud trustworthiness. Non-technical criteria can supplement the role of technical standards in addressing underlying concerns about government access and control of cloud data and services.

Cloud Cybersecurity Certifications Are Critical Points of Commonality and Conflict

Global cloud certification schemes vary considerably in the number and types of technical controls, their recognition of international standards, and their approach to verification (whether they use external audits or self-assessments). (See table 1.)

The programs listed in table 1 are not exhaustive but do provide an indicative comparison of some major cloud certifications and their key features. There are international, country, sectoral, and cross-cutting cloud/ICT certification regimes. For example, the CCRA is one of the few globally recognized programs for mutual recognition (there are accredited labs in multiple countries) for IT security evaluations. It has certified 31 products under its “trusted computing” product category.[73] Many firms also use the SOC 2 security and compliance standard (developed by the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants).[74]

Many countries have cloud certification programs for firms to provide services to the government, such as the U.S. FedRAMP, Australia’s Information Security Registered Assessors Program (IRAP), and Germany’s C5 systems. These certifications provide a harmonized assessment of cloud services (instead of each government agency doing its own assessment). Many of these certifications use international ISO/IEC standards (such as Spain’s and Germany’s) or use a local standard or set of technical requirements that extensively (to reduce the compliance burden) overlap with international standards. For example, the U.S. FedRAMP cloud cybersecurity regime uses the security and privacy technical control catalog from the U.S. National Institute for Standards and Technology (NIST).[75] This overlaps extensively with ISO 27001.

Table 1: Cloud certification regimes

|

Certification |

Country |

Audit Frequency |

Number of Controls |

Submission Language |

ISO Recognition |

Verification Method |

|

ISMAP |

Japan |

Annual |

1,157 |

Japanese |

No |

External audit |

|

FedRAMP |

U.S. |

1/3 assessed annually, full assessment |

25 (Low), 325 (Medium), 421 (High) |

English |

No |

External audit |

|

BSI C5 |

Germany |

Annual |

121 |

English, German |

Yes |

External audit |

|

ENS |

Spain |

Biennial |

73 |

Spanish |

Yes |

External audit |

|

CSPN |

France |

Triennial |

N/A |

English, French (report produced) |

No |

Third-party evaluation company |

|

AgID |

Italy |

Biennial |

20 |

Italian |

No |

Self-assessment |

|

Cyber Essentials |

U.K. |

Annual |

89 |

English |

No |

Self-assessment |

|

Cyber Essentials |

U.K. |

Annual |

89 |

English |

No |

External audit |

|

IRAP |

Australia |

Biennial |

837 |

English |

Can re-use evidence |

External audit |

|

ISO 27001 |

Inter-national |

Annual verification audits, triennial |

93 Annex A Controls |

English |

Yes |

External audit |

|

Common Criteria |

Inter-national |

Five-year life span |

Varies depending on security target |

English |

No |

External audit (certified testing) |

Map and Work to Align Technical Controls and Standards, Audits, and Cloud Certification Requirements

Like-minded countries should build greater alignment and interoperability between their respective cloud cybersecurity certifications and their use of technical controls and international standards and certifications. They should map and work to align the technical controls and standards, audits, and certifications for cloud services. This would help improve collective

cloud cybersecurity among like-minded members and reduce compliance and regulatory burdens across their cloud markets. The goal would be to build a clear understanding of their respective certifications, how similar they are, where and how to address gaps and unnecessary duplications, and how to build interoperability and mutual recognition.

Policymakers should develop a common catalog of technical controls: the specific requirements for incident response, configuration management, and all manner of privacy and cybersecurity measures that together are used by technical standards and cloud certification regimes. A catalog would provide like-minded countries with a common language for closer cooperation and alignment on cloud cybersecurity and trustworthiness. Tables 1 and 2 show that technical controls are the building blocks for country and multinational cloud cybersecurity regimes and the technical standards they use. For example, NIST Special Publication 800-53 on information security provides a catalog of over 1,000 security and privacy controls for all U.S. federal information systems and is central to the U.S. FedRAMP certification system.

The technical controls countries use can differ in major and minor ways, even if the goal is the same. Developing a common catalog of technical controls would be valuable, as identifying, listing, and comparing technical controls from different cloud cybersecurity can be difficult due to minor differences in the specific requirements of the technical controls in each country’s cloud certification regime. This would be like the 2018 European Commission report on European Certification Schemes for Cloud Computing and how they map to EU technical controls for cloud (across EU member states, see table 2).[76]

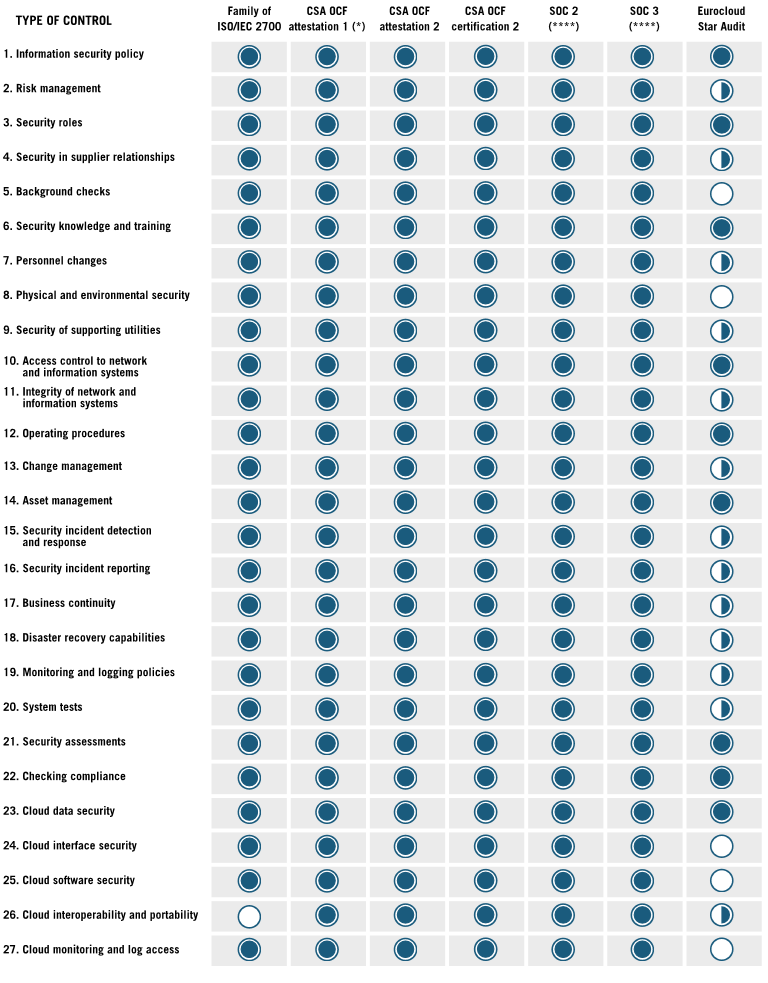

Table 2: Types of technical controls covered in European and international cloud certification programs (full circles are fully covered, half circles are partly covered, empty circles are uncovered)[77]

Policymakers from like-minded countries could designate an existing or new institution to develop a common catalogue of technical controls so that at least they would all be pulling from the same suite of options. A common catalogue of controls would be agnostic in terms of the compliance framework used within, whether it’s in Australia, the United States, or European Union. So even if countries require a different number of controls for different levels of risk, or use them for different frameworks, at least the controls would all be the same.

At the next level up, policymakers should map how their respective cloud cybersecurity regimes relate to core international standards. Such a “cross walk” would compare a regulatory or legal requirement with a standard to identify gaps, conflicts, and commonalities. At this level, the mapping exercise would use international standards to provide the basis for a common language for policymakers from like-minded countries to work together on cloud trustworthiness. Table 3 shows how Singapore’s Multi-Tier Cloud Security (MTCS) maps to a critical international standard for cloud cybersecurity (ISO/IEC 27001) at various risk levels, thus making it easy for firms to see what they already do or need to do to be certified. At Level 3, it shows that firms need to be cross-certified to ISO/IEC 27001 in order to be in compliance.

Table 3: A summary of the differences between Technical Standard ISO/IEC 27001 and Singapore’s Multi-Tier Cloud Security Regime[78]

|

MTCS Level |

Clauses in ISO/IEC2700 |

“Included” |

“Changes” |

“Incremental” |

“New” |

||||

|

1 |

254 |

220 |

87% |

34 |

13% |

32 |

13% |

2 |

1% |

|

2 |

254 |

228 |

90% |

26 |

10% |

25 |

10% |

1 |

1% |

|

3 |

254 |

230 |

91% |

24 |

9% |

24 |

9% |

0 |

0% |

Policymakers should also map their respective use of audits in cloud certifications and their requirements for audits (in terms of third-party audits and the certifications for audit firms).[79] Audits are a critical way to ensure that technical controls and standards for cybersecurity, privacy, and other relevant legal and regulatory requirements exist in practice and not just on paper. As table 1 shows, transparent, periodic audits by independent, trusted, and certified third-party auditors are part of most countries’ public service cloud cybersecurity certification regimes. Policymakers could develop compatible requirements for cloud audits to minimize the compliance burden for firms operating across markets and develop mechanisms that would allow an audit done in one jurisdiction to be recognized in others. This would build on existing arrangements such as the CCRA for the evaluation and certification of IT products for security.[80]

Like-minded countries need to map and build a common technical foundation for cloud cybersecurity. Policymakers should develop a common catalog of technical controls and standards, among other components, to build alignment and interoperability between cloud cybersecurity certifications.

Mapping exercises of technical controls and standards and audits would provide a foundation for discussions about how to build interoperability, and potential mutual recognition, between cloud certification frameworks. In comments that also apply to non-EU countries, Thierry Breton’s, European commissioner for Internal Market of the European Union, response to a question from the European Parliament about EUCS was, “Country-specific cloud security certification schemes are generating silos, market fragmentation and enormous costs of compliance and certification, especially to smaller players who wish to provide their cloud services across the EU.”[81] An agenda for mapping and alignment would improve cloud cybersecurity, improve competition in the sector, and reduce compliance costs. Ideally, countries would set up mutual recognition arrangements so that firms that undergo an audit and certification in one country can use them in other countries. For example, New Zealand recognizes Australia’s cloud cybersecurity certification (IRAP).[82]

Government Access to Data: Assessing Legal Frameworks and What Happens in Practice

Policymakers are concerned about broad and unconstrained legal, extra-legal, and extra-territorial government access to data held by tech firms, especially cloud firms. Policymakers are worried that certain governments, namely China, have largely unfettered access to data—and services—managed by cloud providers in their jurisdiction and overseas subsidiaries. This raises concerns regarding privacy, free speech, other human rights (given access to data can be used for surveillance and political repression) and national security (given data can be used for espionage and other intelligence purposes). The G7 and other countries have taken collective steps to address these concerns, but much more needs to be done to address this foundational issue of global technology governance.

Policymakers need to initiate research, information sharing, and policy debates about the legal frameworks governments use to access data held by private firms and how they work in practice, how they compare with the principles in the OECD Trusted Government Access to Data initiative, and whether they include sufficient legal safeguards. Given the opaque nature of how many governments access data held by private entities, policymakers from like-minded countries need to do more to shed light on how it works in practice, as it is otherwise hard to assess how China and other nations actually uses their legal (or extralegal) powers to compel access to data held by tech firms.

Concerns about government requests and access to data held by tech firms are not new. The Snowden revelations about U.S. government surveillance led to a corresponding wave of privacy and surveillance reforms around the world, including in the United States.[83] The United States and European Union have since negotiated a series of agreements, the latest being the Transatlantic Data Privacy Framework, to provide privacy and surveillance safeguards for EU personal data flowing to the United States. This is a critical distinction between rule-of-law and privacy-respecting countries such as the United States and countries such as China and Russia. Surprisingly, the EU has not acted against EU personal data going to Russia and China, despite the lack of meaningful protections against government access to data held by private firms in those countries. The reality is the EU has not expressed anywhere near the same level of concern regarding EU citizens’ personal data protections when that data is possessed by Chinese or Russian firms, as compared with U.S. firms.

U.S. and other policymakers frequently highlight the broad and ambiguous provisions in China’s national security, intelligence, and cybersecurity laws to argue that Chinese citizens and firms are subject to direct orders from the government, including its intelligence agencies.[84] An extensive legal analysis suggests that it would be challenging for any Chinese citizen or company to resist direct requests from Chinese security or law enforcement agencies.[85] And a European Data Protection Board analysis shows that China lacks legal protections against government surveillance.[86]

However, despite years of accusations and insinuations, there are few details about how China’s government access to private sector data works in practice, such as the frequency and types of data requested/accessed and the legal or extralegal mechanisms used. Government statements and media reports rarely elaborate on the exact nature and frequency of Chinese government access to data.[87] The situation is opaque and likely involves intelligence and security agencies. It’s complicated, as the Chinese Community Party is intertwined with tech firms via personnel and ownership stakes, as is it across most firms in China.[88] The most common scenario is for media reports and government officials to quote or refer to anonymous U.S. intelligence officials and vague intelligence assessments that China combines government data taken via espionage operations (e.g., from hacking the U.S. Office of Management and Budget) and commercial data taken from other hacks (e.g., from the credit-reporting firm Equifax) to pursue targeted intelligence and espionage activities—and that China gets Chinese tech firms to help piece it together.[89] This is the subtext of the June 2021 Biden administration Executive Order on Protecting Americans’ Sensitive Data from Foreign Adversaries.[90] TikTok’s “Project Texas” is indicative of this situation in that a lot of the public information on whether and how TikTok’s parent company ByteDance accesses U.S. data has come from former employees.[91] While useful, this does not provide a solid foundation for major policy changes in the United States and elsewhere.

Chinese courts cannot be relied on to protect firms in the case that the Chinese government pursues illegitimate and illegal access to data and services held by private firms.. At the heart of the problem with countries such as China is that their cloud firms do not have a legal mechanism to refuse government requests for data—and even if they did, it could be redundant if the host country does not have an independent judiciary. In essence, Chinese government power is insufficiently constrained by law, particularly where state security concerns are invoked.[92] The situation in China is instructive, as it highlights the importance of transparency around government access to data and assessing whether a country has relevant privacy, cybersecurity, and surveillance laws and an independent judiciary and genuine rule of law.

Firms in the United States, United Kingdom, European Union, and many other rule-of-law countries with an independent judiciary and privacy and other legal protections can use courts to challenge illegitimate government requests for data. Yet, government access to data held by private firms is far from a China-only issue. There are ongoing concerns about transparency and legal oversight and redress regarding government access to data in the United States, the European Union, and elsewhere. For example, the U.S. Foreign Intelligence Surveillance (FISA) Court has long been criticized for rubber-stamping orders with little to no oversight or transparency. However, there are major efforts to reform this system and associated issues (e.g., nondisclosure orders).[93] The difference is that these issues get substantial public attention in the United States and there is the realistic chance that revisions can be enacted to change and constrain government power, which is different from China and many other countries.

There are few specific details about how China’s government access to private sector data and services works in practice. Policymakers need to present detailed evidence about the nature of the risk associated with China to justify some of the sweeping policy proposals they’re putting forward with regard to cloud, data privacy, cybersecurity, and national security.

Policymakers should identify legal and other data to conduct a holistic assessment about the risk of compelled government access and control over a cloud firm. This should include a thorough legal analysis, similar to the European Data Protection Board report on government access to data in China, India, and Russia. Privacy, cybersecurity, and other laws and legal system characteristics are measurable and comparable, and are what matter in terms of assessing the risks of domestic and extraterritorial government access to data held by cloud firms. These are also measurable (to a degree) when assessing whether governments have broad and arbitrary legal authority to access data held by cloud firms. For example, China ranks 134th out of 142 countries on the World Justice Project’s index of constraints on government powers.[94]

Like-minded countries should address the lack of transparency around government access to data in problematic countries by declassifying intelligence (wherever possible), researching open-source information, conducting confidential surveys, and sharing, aggregating, and anonymizing cases that relate to legal, extra-legal, and extra-territorial government access to data from problematic jurisdictions. Doing so would build off the OECD Trusted Government Access to Data initiative.[95] Policymakers need to do a much better job of presenting clear and detailed evidence about the nature of the risk associated with China and other jurisdictions to justify some of the sweeping policy proposals they’re putting forward with regard to cloud, cybersecurity, data privacy, and national security.

Transparency Reports About Government Requests for Data Provide Critical Transparency and Data on Cloud Trustworthiness

Firms and states should be transparent about the request/receipt and consideration of government requests for access to data held by private firms, such as cloud firms. Transparency promotes accountability and openness and builds trust between users, cloud firms, and governments. Transparency reports also help differentiate cloud firms that are serious about their responsibility to protect user data from illegitimate government requests for data and those firms that are not. Policymakers should encourage cloud firms to release transparency reports on an annual basis to inform both governments and the public about how they manage government requests for data.[96]

Transparency reports could be considered a proxy for whether cloud firms are cooperative in receiving, assessing, and responding to legitimate government requests for data, and also whether they’re willing and able to reject requests that don’t pass legal and human rights assessments. This proxy measurement is critically important given it contrasts with the many U.S. and European firms that have issued transparency reports with a complete lack of transparency and data about if/how Chinese firms respond to requests for data in China, never mind Russia and other problematic countries.

Transparency reports about government requests for data, and firms’ responses, should become a standard, best practice feature among global cloud firms.

Many U.S. and other non-Chinese tech and cloud firms commonly challenge government demands for data that they believe are overly broad and not legally valid. Firms are often in the difficult position of considering requests from governments and assessing whether they are legally valid and do not undermine the their values in terms of protecting human rights such as privacy. Public disclosures about their demonstrated willingness to do this is an important data point for considering cloud trustworthiness. For example, from July to December 2022, Google received 192,408 requests to disclose user information, and in 79 percent of cases, it disclosed some information. Google received 1,687 requests for data via diplomatic legal requests.[97] From July to December 2022, Microsoft rejected nearly 24 percent (5,760 requests) of law enforcement requests for data, as they did not meet legal requirements.[98]

Unfortunately, since 2013, the growth rate of firms publishing transparency reports has been steadily decreasing. Since Google released the first transparency report in 2010, 88 companies around the world have released reports (up to 2021).[99] AliCloud and Tencent Cloud do not provide transparency reports (while TikTok does).[100] However, due to different accounting and reporting practices, and a lack of clarity about exactly how companies are counting or defining certain terms, it is difficult to compare reports from different firms.[101] Many firms disclose how many requests for data they receive and from which countries, while only some break this data down by requesting agency, the legal basis for the request, whether data was disclosed, and whether they disclosed data that was located outside the requesting jurisdiction (given concerns about China’s extraterritorial requests for data).[102]

Transparency reports should become a standard, best practice feature among global cloud firms. Policymakers and cloud firms should develop or agree on a standardized transparency report template, such as the Transparency Reporting Toolkit designed by the Open Technology Institute and the Berkman Klein Center For Internet & Society.[103] To their credit, several major tech firms (including Amazon, Google, SAP, IBM, CISCO, and Microsoft) are advocating for more transparency reports as part of their “Trusted Cloud Principles.”[104]

Government Operational Control Over Cloud Services

Policymakers are increasingly concerned about the ability of foreign adversaries to not just compel cloud firms to hand over data but assume operational control over the workloads cloud firms manage in the event of a major cybersecurity incident or conflict. This relates to both technical and legal criteria, as it depends on an assessment of whether there is a clear separation of power and control (from a corporate ownership perspective) between a cloud firm and its home government and whether there are technical separation measures in place.[105]