Comments to the NIST Regarding the Draft Interagency Guidance Framework for Considering the Exercise of March-In Rights

Introduction

This submission represents the views of the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF), a non-profit, non-partisan think tank focused on the intersection of technological innovation and public policy. ITIF offers them in response to the Department of Commerce (DOC) National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST)’s and the Interagency Working Group for Bayh-Dole (IAWBD)’s “Request for Information Regarding the Draft Interagency Framework for Considering the Exercise of March-in Rights.”[1]

Broadly, ITIF contends that the technology transfer regime the United States has implemented over the past four decades, largely as enabled through the University and Small Business Patent Procedures Act—better known as the Bayh-Dole Act—has been tremendously effective in stimulating U.S. innovation. The current system is not nearly broadly in need of serious modification or reform, which would likely be counterproductive to a largely well-functioning technology transfer system that effectively transmits technologies to private-sector companies, especially entrepreneurial small businesses, which are willing to assume the risk and expense of trying to commercialize innovations deriving from the intellectual property (IP) stemming from federally funded research and development (R&D) that often occurs at U.S. universities. In particular, this submission will contend that making the price of a resulting product a legitimate basis for the application of Bayh-Dole march-in rights would have deleterious impacts on both the effectiveness of the Bayh-Dole Act and the broader U.S. innovation system.

A Lesson: The History of U.S. Life Sciences Competitiveness

The United States has come to be the world’s leader in life-sciences innovation, as it has been across a number of advanced-technology industries. Indeed, in every five-year period since 1997, the United States has produced more new chemical or biological entities than any other country or region in the world. From 1997 to 2016, U.S.-headquartered enterprises accounted for 42 percent of new chemical or biological entities introduced in the world, far outpacing relative contributions from European Union (EU) member countries, Japan, China, or other nations.[2] Moreover, the United States has become the world’s largest funder of biomedical R&D investment in recent decades, with one (2008) study estimating that the U.S. share of global biomedical R&D funding reached as high as 80 percent over the preceding two decades.[3] Put simply, since the start of this millennium, U.S.-headquartered biopharmaceutical enterprises have accounted for almost half of the world’s new drugs.

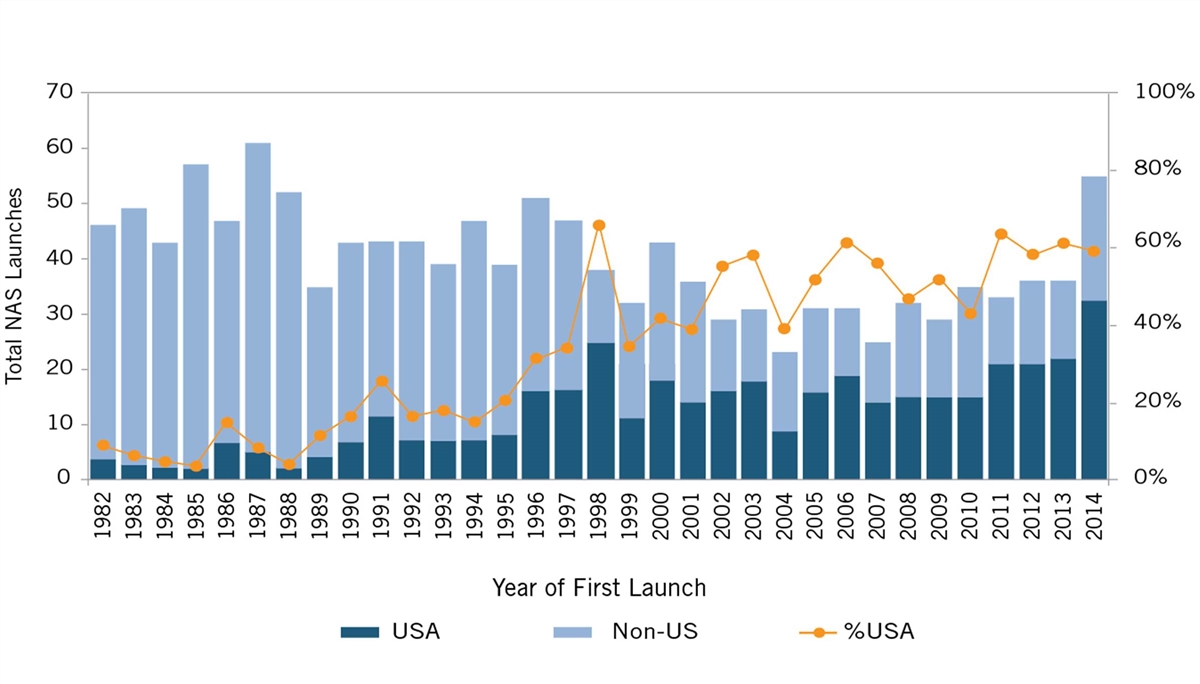

But U.S. leadership in life-sciences innovation wasn’t always a given; in fact, for most of the post-World War II-era, the United States was a global “also-ran” in life-sciences innovation. Between 1960 and 1965, European companies invented 65 percent of the world’s new drugs, and in the latter half of the 1970s, European-headquartered enterprises introduced more than twice as many new drugs to the world as did U.S.-headquartered enterprises (149 to 66).[4] In fact, throughout the 1980s, fewer than 10 percent of new drugs were introduced first in the United States.[5] (See figure 1.) America wasn’t inventing new-to-the world drugs, let alone getting them to its citizens first.

Figure 1: U.S. share of new active substances launched on the world market, 1982–2019[6]

That the United States subsequently flipped the script and has become the world’s life-sciences innovation leader has not been accidental or incidental. Rather, as ITIF argues in “Why Life-sciences Innovation Is Politically Purple,” U.S. life-sciences leadership today is the result of a series of conscientious and intentional public policy decisions designed to make America the world’s preeminent location for life-sciences research, innovation, and product commercialization.[7] The United States did so with robust and complementary public and private investment in biomedical R&D; supportive incentives, including tax policies, to encourage biomedical investment; robust IP rights; an effective regulatory and drug-approval system; a drug-pricing system that allows innovators to earn sufficient revenues to enable continued investment into future generations of biomedical innovation; and, lastly, the world’s best system to support technology transfer and commercialization, especially with regard to translating technologies stemming from federally funded R&D to the private sector.

It’s a strong example of a U.S. industry where effective and well-conceived public and private policies, investments, and partnerships contributed to make America the world’s leader, and it’s a good example of the type of industry that’s America’s to lose if policymakers don’t continually tend to advancing a supportive policy environment.

Innovative U.S. Technology Transfer and Commercialization Policies

As with life-sciences innovation, the United States was long a laggard in technology transfer and commercialization practices, especially with regard to the licensing of technologies stemming from federally funded R&D. As late as 1978, the federal government had licensed less than 5 percent of the as many as 30,000 patents it owned.[8] Likewise, throughout the 1960s and 1970s, many American universities shied away from direct involvement in the commercialization of research.[9] Indeed, before the passage of Bayh-Dole, only a handful of U.S. universities even had technology transfer or patent offices.[10]

Aware as early as the mid-1960s that the billions of dollars the federal government was investing in R&D were not paying the expected dividends, President Johnson in 1968 asked Elmer Staats, then the comptroller general of the United States, to analyze how many drugs had been developed from NIH-funded research. Johnson was stunned when Staats’s investigation revealed that “not a single drug had been developed when patents were taken from universities [by the federal government].”[11] As his report to Congress elaborated:

At that time we reported that HEW [the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, predecessor of the Department of Health and Human Services] was taking title for the Government to inventions resulting from research in medicinal chemistry. This was blocking development of these inventions and impeding cooperative efforts between universities and the commercial sector. We found that hundreds of new compounds developed at university laboratories had not been tested and screened by [the] pharmaceutical industry because the manufacturers were unwilling to undertake the expense without some possibility of obtaining exclusive rights to further development of a promising product.[12]

The Congressional response to this conundrum was the Bayh-Dole Act, passed in 1980, which afforded contractors—such as universities, small businesses, and nonprofit research institutions—rights to the intellectual property generated from federal funding. The legislation’s impact was immediate, powerful, and long-lasting. It has been widely praised as a significant factor contributing to the United States’ “competitive revival” in the 1990s.[13] In 2002, The Economist called Bayh-Dole:

Possibly the most inspired piece of legislation to be enacted in America over the past half-century. Together with amendments in 1984 and augmentation in 1986, this unlocked all the inventions and discoveries that had been made in laboratories throughout the United States with the help of taxpayers’ money. More than anything, this single policy measure helped to reverse America's precipitous slide into industrial irrelevance.[14]

Allowing U.S. institutions to earn royalties through the licensing of their research has provided a powerful incentive for universities and other institutions to pursue commercialization opportunities.[15] Indeed, the Bayh-Dole Act almost immediately led to an increase in academic patenting activity. For instance, while only 55 U.S. universities had been granted a patent in 1976, 240 universities had been issued at least one patent by 2006.[16] Similarly, while only 390 patents were awarded to U.S. universities in 1980, by 2009, that number had increased to 3,088—and by 2015, to 6,680. Another analysis found that in the first two decades of Bayh-Dole (i.e., 1980 to 2002) American universities experienced a tenfold increase in their patents and created more than 2,200 companies to exploit their technology.[17]

That impact has only continued to grow. In fact, according to a 2022 Association of University Technology Managers (AUTM) report, from 1996 to 2017, academic patents and their subsequent licensing to industry—substantially stimulated by the Bayh-Dole Act—bolstered U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) by up to $1 trillion, contributed to $1.9 trillion in gross U.S. industrial output, and supported 6.5 million jobs.[18] Moreover, U.S. academic technology transfer activities have produced 495,000 invention disclosures, 126,000 U.S. patents issued, and 17,000 startups formed, with 73 percent of university licenses flowing to startups and small companies.[19] Perhaps most importantly for public health, more than 200 drugs and vaccines have been developed through public-private partnerships since the Bayh-Dole Act entered force in 1980.[20]

On average, three new start-up companies and two new products are launched in the United States every day as a result of university inventions brought to market, in part thanks to the Bayh-Dole Act.[21] And as Harvard University’s Naomi Hausman has written, “The sort of large scale technology transfer from universities that exists today would have been very difficult and likely impossible to achieve without the strengthened property rights, standardized across granting agencies, that were set into law in 1980.”[22]

The Bayh-Dole Act has produced a number of additional benefits. For example, Hausman analyzed the impact of Bayh-Dole in shaping university relations with local economies and found that the increase in university connectedness to industry under the IP regime created by Bayh-Dole produced important local economic benefits. In particular, Hausman found that long-run employment, payroll, payroll per worker, and average establishment size grew differentially more after the 1980 Bayh-Dole Act in industries more closely related to innovations produced by a local university or hospital.[23] There is also evidence that the Bayh-Dole Act contributed to university faculty responding to royalty incentives by producing higher-quality innovations.[24] Evidence further suggests that patenting increased most after Bayh-Dole in lines of business that most value technology transfer via patenting and licensing.[25]

As ITIF has written, policymakers helped revitalize U.S. competitiveness in the late 1970s/early 1980s through a number of Congressional and Reagan administration actions (the groundwork for many of which were laid in the Carter administration) including passage of the Stevenson-Wydler Act, the Bayh-Dole Act, the National Technology Transfer Act, and the Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act. Collectively they created a long list of alphabet-soup programs to boost innovation, including SBIR (Small Business Innovation Research), NTIS (National Technical Information Service—expanded), SBIC (Small Business Investment Company—reformed), MEP (Manufacturing Extension Partnership), and CRADAs (cooperative research and development agreements).[26] It's important to recognize that these represent complementary programs and initiatives. In particular, the Bayh-Dole Act, by helping turn America’s universities into engines of innovation and providing the IP feedstock to support start-up companies, has played an important role in turning the SBIR program into the tremendous success it has become.

Launched in 1982 (two years after Bayh Dole), since its inception SBIR has issued over 160,000 awards and enterprises funded through SBIR vehicles have since produced 70,000 issued patents, 700 public companies, and $41 billion in venture capital (VC) investments.[27] Although SBIR accounts for only 3.2 percent of extramural research funding (about $2.5 billion annually), this funding generates significantly outsized returns. For instance, a 2008 ITIF study of the U.S. national innovation system from 1970 to 2006 found that SBIR-nurtured firms consistently accounted for about one-quarter of all U.S. R&D 100 Award winners, signaling that SBIR-supported firms were regularly contributing some of the most breakthrough innovations to the U.S. economy.[28] Looking across all federal agencies, various National Academies studies have found that commercialization rates from SBIR/STTR Phase II awards range from 40 to 70 percent, varying by federal agency.[29] Those studies have also found that SBIR plays a major role in making projects that would not happen otherwise possible.[30] In short, America’s well-functioning SBIR system depends upon a well-functioning Bayh-Dole-enabled technology licensing system, and if the former is compromised then the latter certainly would be as well.

Finally, countries throughout the world—including Brazil, China, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, South Africa, and Taiwan—have since followed the United States’ lead in establishing policies that grant their universities IP ownership rights.[31] Even Kazakhstan and Zimbabwe have looked at implementing Bayh-Dole-like legislation, recognizing its power to help turn their universities into engines of innovation and commercialization. Likewise, the California Senate Office of Research conducted a comprehensive analysis of the Bayh-Dole Act and concluded: “After reviewing the literature and interviewing key experts, we recommend the Legislature consider adopting a statewide IP policy replicating the principles of the Bayh–Dole Act for research granting programs.”[32] U.S. states and foreign countries have supported adoption of Bayh-Dole-like policies because they recognize that Bayh-Dole works. Simply put, the Bayh-Dole Act has created a powerful engine of practical innovation, producing many scientific advances that have extended human life, improved its quality, and reduced suffering for millions of people.[33]

The Risks That Inappropriate Use of March-In Rights Pose to the Bayh-Dole Act

In short, the Bayh-Dole Act has been an unparalleled success. Yet some have advocated for policies that would undermine some of its key provisions and effects. At issue are so-called march-in rights, a provision within the Bayh-Dole Act that permits the U.S. government, in specified, proscribed, and limited circumstances, to require patent holders to grant a “nonexclusive, partially exclusive, or exclusive license” to a “responsible applicant or applicants.”[34] As the following section explains, the architects of the Bayh-Dole Act principally intended for march-in rights to be used to ensure patent owners commercialized their inventions.[35] As Senator Birch Bayh explained:

When Congress was debating our approach fear was expressed that some companies might want to license university technologies to suppress them because they could threaten existing products. Largely to address this fear, we included the march-in provisions.[36]

Yet a number of civil society organizations and some members of Congress have called on agencies such as the National Institute of Health (NIH) to exploit Bayh-Dole march-in rights to “control” allegedly unreasonably high drug prices. (Though, as ITIF has written, these advocates’ assertions that U.S. drug prices, on net, are unreasonably high are fundamentally unwarranted and unsubstantiated.)[37] Nevertheless, numerous petitions requesting NIH to “march in” with respect to a particular pharmaceutical drug have been filed. A 2016 Congressional Research Service (CRS) report which investigated the matter found that of the six petitions that had been filed to NIH at that time, four were filed by civil society organizations alleging that a company was pricing a drug too high.[38] Some 50 members of Congress, led by Representative Lloyd Doggett (D-TX), have called on the NIH to cancel exclusivity when patented drugs are not available with reasonable terms.[39] Senator Angus King (I-ME) proposed legislation in 2017 that would require the Department of Defense (DOD) to issue compulsory licenses under Bayh-Dole “whenever the price of a drug, vaccine, or other medical technology is higher in the U.S. than the median price charged in the seven largest economies that have a per capita income at least half the per capita income of the U.S.”[40] In other words, DOD would force a licensor to divulge their intellectual property so that a drug could be manufactured by other licensees, and in theory be sold at a lower price. (While it was not enacted, a similar provision was unfortunately included in the FY 2018 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) Senate Armed Services Committee report.) Yet the reality is that the Bayh-Dole Act’s designers did not intend for march-in rights to be used to control either drug prices, or the price of any other downstream product.

Bayh-Dole March-In Rights Were Never Intended to Address Price Concerns

The Bayh-Dole Act proscribes four specific instances in which the government is permitted to exercise march-in rights:

1. If the contractor or assignee has not taken, or is not expected to take within a reasonable time, effective steps to achieve practical application of the subject invention;

2. If action is necessary to alleviate health or safety needs not reasonably satisfied by the patent holder or its licensees;

3. If action is necessary to meet requirements for public use specified by federal regulations and such requirements are not reasonably satisfied by the contractor, assignee, or licensees; or

4. If action is necessary, in exigent cases, because the patented product cannot be manufactured substantially in the United States.[41]

In other words, lower prices are not one of the rationales laid out in the act. In fact, as senators Bayh and Dole have themselves noted, the Bayh-Dole Act’s march-in rights were never intended to control or ensure “reasonable prices.”[42] As the twain wrote in a 2002 Washington Post op-ed titled, “Our Law Helps Patients Get New Drugs Sooner,” the Bayh-Dole Act:

Did not intend that government set prices on resulting products. The law makes no reference to a reasonable price that should be dictated by the government. This omission was intentional; the primary purpose of the act was to entice the private sector to seek public-private research collaboration rather than focusing on its own proprietary research.[43]

The op-ed reiterated that the price of a product or service was not a legitimate basis for the government to use march-in rights, noting:

The ability of the government to revoke a license granted under the act is not contingent on the pricing of a resulting product or tied to the profitability of a company that has commercialized a product that results in part from government-funded research. The law instructs the government to revoke such licenses only when the private industry collaborator has not successfully commercialized the invention as a product.[44]

Rather, Bayh-Dole’s march-in provision was designed as a fail-safe for limited instances in which a licensee might not be making good-faith efforts to bring an invention to market, or when national emergencies require that more product is needed than a licensee is capable of producing. As Joseph P. Allen, a senate staffer for Bayh who played a key role in shaping the legislation, explains, Congress’s introduction of Bayh-Dole was intended “to decentralize patent management from the bureaucracy into the hands of the inventing organizations, while retaining the long-established precedent that march-in rights were to be used in rare situations when effective efforts are not being made to bring an invention to the marketplace or enough of the product is not being produced to meet public needs.”[45]

Likewise, a 2018 NIST report “Return on Investment Initiative: Draft Green Paper” agreed, noting, “The use of march-in is typically regarded as a last resort, and has never been exercised since the passage of the Bayh-Dole Act in 1980.”[46] That report noted that, “NIH determined that the use of march-in to control drug prices was not within the scope and intent of the authority.”[47]

In fact, there has only been one case in which Bayh-Dole’s march-in criteria truly would have been met: a 2010 case in which Genzyme encountered difficulties in manufacturing sufficient quantities of Fabrazyme/agalsidase beta, an orphan drug for the treatment of Fabry disease.[48] Genzyme had to shut down the plant making the drug due to quality control issues and was therefore unable to manufacture the drug in sufficient quantities. NIH investigated the situation but did not initiate a march-in proceeding because it found that “Genzyme was working diligently to resolve its manufacturing difficulties” and that the company was likely to get back into production faster than a new licensee could get FDA approval to make the drug.[49]

Indeed, march-in rights have never been exercised during the now over-40-year history of the Bayh-Dole Act.[50] NIH has denied every petition to apply march-in rights, noting that the drugs in question were in virtually all cases adequately supplied and that concerns over drug pricing were not, by themselves, sufficient to provoke march-in rights.[51] NIH itself has expressed skepticism about the use of march-in rights to control drug prices, noting:

Finally, the issue of the cost or pricing of drugs that include inventive technologies made using federal funds is one which has attracted the attention of Congress in several contexts that are much broader than the one at hand. In addition, because the market dynamics for all products developed pursuant to licensing rights under the Bayh-Dole Act could be altered if prices on such products were directed in any way by NIH, the NIH agrees with the public testimony that suggested that the extraordinary remedy of march-in is not an appropriate means of controlling prices.[52]

As Rabitschek and Latker wrote in “Reasonable Pricing—A New Twist for March-in Rights Under the Bayh-Dole Act” in the Santa Clara University High Technology Law Journal, “A review of the [Bayh-Dole] statute makes it clear that the price charged by a licensee for a patented product has no direct relevance to march-in rights.”[53] As the authors concluded:

There is no reasonable pricing requirement under 35 U.S.C. §203(l)(a)(1), considering the language of this section, the legislative history, and the prior history and practice of march-in rights. Rather, this provision is to assure that the contractor utilizes or commercializes the funded invention.[54]

The argument that Bayh-Dole march-in rights could be used to control drug prices was originally advanced in an article by Peter S. Arno and Michael H. Davis.[55] They contended that “[t]he requirement for ‘practical application’ seems clear to authorize the federal government to review the prices of drugs developed with public funding under Bayh-Dole terms and to mandate march-in when prices exceed a reasonable level” and suggested that under Bayh-Dole, the contractor may have the burden of showing that it charged a reasonable price.[56] While Arno and Davis admitted there was no clear legislative history on the meaning of the phrase “available to the public on reasonable terms,” they still concluded that, “[t]here was never any doubt that this meant the control of profits, prices, and competitive conditions.”[57]

But as Rabitschek and Latker explain, there are several problems with this analysis. First, the notion that “reasonable terms” of licensing means “reasonable prices” arose in unrelated testimony during the Bayh-Dole hearings. Most importantly, they note, “If Congress meant to add a reasonable pricing requirement, it would have explicitly set one forth in the law, or at least described it in the accompanying reports.”[58] As Rabitschek and Latker continue, “There was no discussion of the shift from the ‘practical application’ language in the Presidential Memoranda and benefits being reasonably available to the public, to benefits being available on reasonable terms under 35 U.S.C. § 203.”[59] As they conclude, “The interpretation taken by Arno and Davis is inconsistent with the intent of Bayh-Dole, especially since the Act was intended to promote the utilization of federally funded inventions and to minimize the costs of administering the technology transfer policies…. [The Bayh-Dole Act] neither provides for, nor mentions, ‘unreasonable prices.’”[60]

Again, the Bayh-Dole Act’s march-in provisions were included with commercialization in mind. Related to this, another reason the Bayh-Dole Act’s architects inserted march-in right provisions was because, at the time the law was introduced, very few universities were experienced in patent licensing. The march-in provision therefore served as a fail-safe for cases in which universities were not effectively monitoring their agreements.[61] But universities have in fact proven proactive and effective in enforcing their licensing agreements, regularly including development milestones in their licenses—and when these milestones aren’t being met without satisfactory reason (e.g., development is more difficult than expected), universities often terminate the deal and look for another developer. In other words, universities are enforcing their licensing agreements, not letting licenses just sit on the technologies—another example of why there has been no reason for the government to march in.

Put simply, the price of a resulting product is not—and has never been—a justification for the application of Bayh Dole march-in rights. That DOC NIST is now directing agencies to consider price as a possible factor for use in Bayh-Dole march-in rights is an extralegal administrative action that has no legislative or statutory basis whatsoever. Specifically, the Interagency Guidance Framework contains guidelines for understanding “Is a Statutory Criteria Met?” “Criterion 1” considers whether “Action is necessary because the contractor or assignee has not taken, or is not expected to take within a reasonable time, effective steps to achieve practical application of the subject invention in such field of use.”[62] In discussing how an agency might discuss this criterion, the framework writes march-in rights might be considered warranted, “If the contractor or licensee has commercialized the product, but the price or other terms at which the product is currently offered to the public are not reasonable, agencies may need to further assess whether march-in is warranted.”[63] However, there is simply nothing in federal law that affords federal agencies the authority to exercise Bayh-Dole march-in rights on this basis.

Using March-In Rights to Address Drug Pricing Would Significantly Reduce U.S. Innovation

Weakening the certainty of access to IP rights provided under Bayh-Dole by employing march-in (or other reasonable pricing requirements) to address price concerns—especially if it meant a government entity could walk in and retroactively commandeer innovations private-sector enterprises invested hundreds of millions, if not billions, to create—would significantly diminish private businesses’ incentives to commercialize products supported by federally funded research.[64] As David Bloch notes, “The reluctance of such [biopharmaceutical] companies to do business with the government is almost invariably tied up in concerns over the government’s right to appropriate private sector intellectual property.”[65] As he continues, “Each march-in petition potentially puts at risk the staggeringly massive investment that branded pharmaceutical companies make in developing new drug therapies.”[66]

And, of course, that dynamic applies not only to America’s life-sciences industry, but to all U.S. advanced technology industries. Indeed, as the framework states, “The framework is not meant to apply to just one type of technology or product or to subject inventions at a specific stage of development.”[67] The Bayh-Dole Act has contributed to the commercialization of innovations in a range of other sectors beyond the life sciences, including to autonomous vehicles, quantum computing, firefighting drones, high-definition televisions, neoprene, and even Honeycrisp apples.[68] If the U.S. government, a competitor, or any given petitioner decided they felt the resulting price of any such product were too high, the proposed Bayh-Dole guidance framework in theory opens the door for a march-in petition.

Given such potential wide-ranging impact, it’s quite likely that private sector actors will take a much more cautious approach when licensing Bayh-Dole- impacted IP from U.S. universities. And that’s of significant consequence, for, as noted, 70 percent of university patent licenses go to small firms. These firms incidentally play an outsized role in U.S. life-sciences innovation, with small businesses accounting for more than seven in ten drug candidates currently in Phase III (pivotal-stage) clinical trials.[69] In fact, America is home to 85 percent of the world’s small, research-intensive biopharma firms.[70]

Venture capitalists, who play such a critical role in providing risk finance for early-stage entrepreneurs, will likely think twice about providing funding to nascent companies trying to commercialize Bayh-Dole-impacted IP. The companies venture capitalists fund already encounter significant market, technological, legal, and financial risks, making it difficult enough to forecast future profits and cashflows. But now adding to this calculus the reality that the U.S. government may—years or even decades hence—declare that a resulting product’s price is too high and “march-in” on the IP (potentially licensing it too others) would likely only enhance their reticence to invest in Bayh-Dole-empowered startups.

It should also be noted that a wave of march-in petitions should not be expected only from civil society advocates, but also from astute foreign adversaries who could look to the march-in mechanism as a way to stymie American enterprises’ ability to commercialize innovative products at competitive prices. A related concern would be that larger pharmaceutical enterprises (possibly foreign, including Chinese, ones) could credibly argue that—since by definition they have much greater production scale and capability than startup companies do—they could produce a drug much more “price reasonably” than a start-up could, just so long as the government commandeers others’ IP for them, they could manufacture a drug much more cost effectively. And that points to another serious concern: the NIST draft guidelines appear to apply to already-commercialized innovations—not only those that might occur in the future—changing in midstream the rules of the game current licensees had signed onto and undermining trust placed in a long-established system.

Thus, the reality here is that what the Biden administration is proposing is not “Guidance Framework for Considering the Exercise of March-in Rights”; rather, it’s a recipe and how-to guide for undermining America’s world-leading system for spinning innovative technology start-ups out of U.S. universities into powerful private-sector competitors.

The damage price-based march-in rights could cause to the U.S. innovation system isn’t simply hypothetical or theoretical, rather it’s grounded in historical reality. Indeed, the debate around “reasonable pricing” of drugs stemming from licensed research goes back some time. The Federal Technology Transfer Act of 1986 (FTTA) authorized federal laboratories to enter into Cooperative Research and Development Agreements (CRADAs) with numerous entities, including private businesses. NIH has found that CRADAs “significantly advance biomedical research by allowing the exchange and use of experimental compounds, proprietary research materials, reagents, scientific advice, and private financial resources between government and industry scientists.”[71]

In 1989, NIH’s Patent Policy Board adopted a policy statement and three model provisions to address the pricing of products licensed by public health service (PHS) research agencies on an exclusive basis to industry, or jointly developed with industry through CRADAs. In doing so, the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) became the only federal agency at the time (other than the Bureau of Mines) to include a “reasonable pricing” clause in its CRADAs and exclusive licenses.[72] The 1989 PHS CRADA Policy Statement asserted:

DHHS has a concern that there be a reasonable relationship between pricing of a licensed product, the public investment in that product, and the health and safety needs of the public. Accordingly, exclusive commercialization licenses granted for the NIH/ADAMHA [Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration] intellectual property rights may require that this relationship be supported by reasonable evidence.

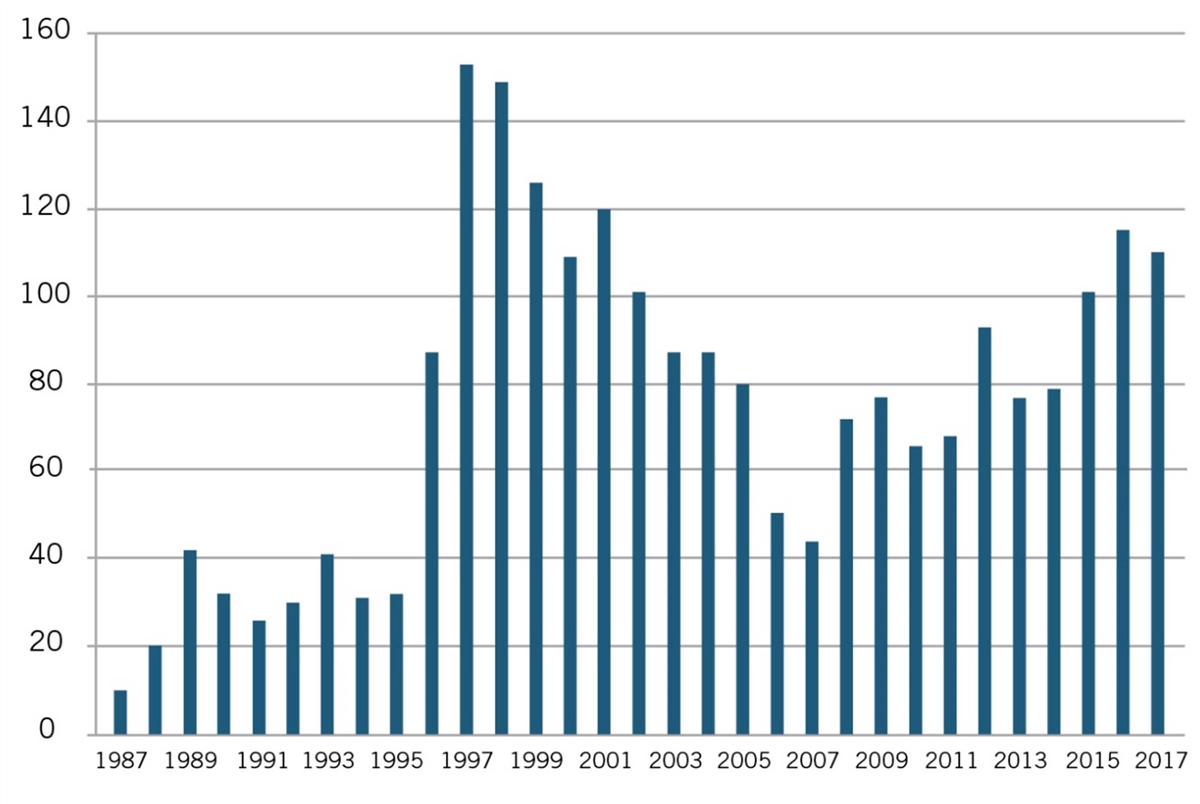

But as Joseph P. Allen notes, such “attempts to impose artificial ‘reasonable pricing’ requirements on developers of government supported inventions did not result in cheaper drugs. Rather, companies simply walked away from partnerships.”[73] Use of CRADAs began in 1987 and rapidly increased until the reasonable pricing requirement hit in 1989, after which they declined through 1995. (See figure 2).

Figure 2: Private-sector CRADAs with NIH, 1987–2017[74]

Recognizing that the only impact of the reasonable pricing requirement was undermining scientific cooperation without generating any public benefits, NIH eliminated the reasonable pricing requirement in 1995. In removing the requirement, then NIH director Dr. Harold Varmus explained, “An extensive review of this matter over the past year indicated that the pricing clause has driven industry away from potentially beneficial scientific collaborations with PHS scientists without providing an offsetting benefit to the public. Eliminating the clause will promote research that can enhance the health of the American people.”[75] As figure 2 shows, after NIH eliminated the requirement in 1995, the number of CRADAs immediately rebounded in 1996, and grew considerably in the following years.[76] The case represents a natural experiment showing the harm pricing requirements can inflict. Somewhat similarly, as the California Senate Office of Research has noted, “Granting agencies such as the National Institutes of Health (NIH) ultimately have abandoned policies that require a financial return to the government after concluding that removing barriers to the rapid commercialization of products represents a greater public benefit than any potential revenue stream to the government.”[77]

Recognizing that the only impact of the reasonable pricing requirement was undermining scientific cooperation without generating any public benefits, NIH eliminated the reasonable pricing requirement in 1995. In removing the requirement, then NIH director Dr. Harold Varmus explained, “An extensive review of this matter over the past year indicated that the pricing clause has driven industry away from potentially beneficial scientific collaborations with PHS scientists without providing an offsetting benefit to the public. Eliminating the clause will promote research that can enhance the health of the American people.”[75] As figure 2 shows, after NIH eliminated the requirement in 1995, the number of CRADAs immediately rebounded in 1996, and grew considerably in the following years.[76] The case represents a natural experiment showing the harm pricing requirements can inflict. Somewhat similarly, as the California Senate Office of Research has noted, “Granting agencies such as the National Institutes of Health (NIH) ultimately have abandoned policies that require a financial return to the government after concluding that removing barriers to the rapid commercialization of products represents a greater public benefit than any potential revenue stream to the government.”[77]

A more recent case involved biopharmaceutical company Sanofi possibly taking a license from the U.S. Army to develop a vaccine for the Zika virus. U.S. Army scientists from the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research developed two candidate vaccines for the Zika virus and posted a notice in the federal register offering to license them on either a nonexclusive or exclusive basis. No company responded to the nonexclusive license, and Sanofi was the only company that submitted a license application for the Army’s Zika candidate vaccine, with the U.S. Army and Sanofi reaching a licensing agreement in June 2016 that would enable Sanofi to continue the development and clinical trial work necessary to turn the candidate vaccine into a market-ready product. As a U.S. Army official noted, “Exclusive licenses are often the only way to attract a competent pharma partner for such development projects,” and are needed because the military lacks “sufficient” research and production capabilities to develop and manufacture a Zika vaccine.[78] Sanofi received a $43 million government grant to start undertaking clinical trial work on the virus candidate.

In July 2017, supported by Knowledge Economy International, an organization opposed to robust intellectual property rights, Sens. Bernie Sanders (D-VT) and Dick Durbin (D-IL) argued that the U.S. Army and Sanofi should insert reasonable pricing language into the exclusive license. Sanders even called on President Trump to cancel the deal.[79] In response, Army officials noted that they were not in a position to “enforce future vaccine prices.” For its part, Sanofi representatives noted, “We can’t determine the price of a vaccine that we haven’t even made yet,” and argued that “it’s premature to consider or predict Zika vaccine pricing at this early stage of development. As noted earlier, ongoing uncertainty around epidemiology and disease trajectory make any commercial projections theoretical at best.”[80] Sanofi noted that it had committed over 60 researchers to the effort, invested millions of dollars itself, and was “committed to leveraging its flavivirus vaccine development and manufacturing expertise to deliver and ultimately price a Zika vaccine in a responsible way.”[81]

Sanofi also noted that the proposed license would require it to pay milestone and royalty payments back to the government, and its exclusive license would not prevent other companies—such as GlaxoSmithKline, Takeda, and Moderna, which also had all struck their own Zika vaccine partnerships with U.S. agencies—from bringing competing products to market, and allow for robust competition in the market for Zika vaccines.[82] However, with both partners continuing to be attacked in the media, in September 2017, Sanofi announced it would “not continue development of, or seek a license from, the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research for the Zika vaccine candidate at this time.”[83] This is yet another case wherein some policymakers’ insistence on pricing requirements stifled innovation and the potential for a firm to bring a promising innovation to market.

It also takes the debate back to the central point that, in their push for lower drug prices through weaker private IP rights stemming from federally funded research, advocates fail to acknowledge that no drugs were created from federally funded inventions under the previous (to Bayh-Dole) regime.[84] In contrast, over 200 new drugs and vaccines have been developed through public-private partnerships facilitated in part by the Bayh-Dole Act since its enactment in 1980.[85]

Using Price as a Basis for March-In Rights Would Likely Harm Innovation Across All Sectors

It seems clear that the Biden administration’s desire to reform Bayh-Dole march-in rights stems from its misguided zeal to control drug prices. To wit, this line from the administration’s December 7, 2003 fact sheet announcing the proposed new guidelines: “Today, the Biden-Harris Administration is announcing new actions to promote competition in health care and support lowering prescription drug costs for American families, including the release of a proposed framework for agencies on the exercise of march-in rights on taxpayer-funded drugs and other inventions, which specifies that price can be a factor in considering whether a drug is accessible to the public.”[86]

But while changes to Bayh-Dole march-in rights would certainly have a highly damaging impact on U.S. biopharmaceutical innovation, its reach to control drug prices might be to some degree limited. In November 2023, the research organization Vital Transformation analyzed a cohort of 361 new FDA-approved medicines from 2011 to 2020 alongside the patent assets protecting them. The study found that 92 percent of the medicines researched were directly discovered by industry, and have no government-interest statement (GIS), federally funded co-development, or federal partnership program associated with any patents core to the development of the medicine.[87] The Vital Transformation research found that less than 10 percent of all drugs assessed had any inventive contribution from government funding, and only 5 of the 361 medicines included a government interest statement in their entire complement of composition of matter and mechanism of action patents.[88] As the authors conclude, this suggests “that less than 2 percent of the new therapies were invented entirely with federal funding support; another 8% have an inventive contribution from federal funding to only some aspect of the drug, and 92% were invented independently without federal support.”[89]

As Vital Transformation CEO Duane Schulthess interprets these findings in light of the proposed Bayh-Dole march-in rights changes, “Even if doing so were lawful, marching in on federally funded IP to only take back fewer than 2% of drugs from over 350 discoveries would have zero impact on national pharmaceutical spending, but would come at the cost of doing irreparable harm to the entire US public/private partnership ecosystem. It’s a policy devoid of economic or scientific reality regarding how the private market will respond to such actions.”[90] In other words, the proposed Bayh-Dole march-in rights changes would inflict indiscriminate and lasting damage across the entire U.S. innovation system, not just in the life-sciences.

The Proposed Framework Uses Ambiguous and Vague Terminology

The proposed interagency framework uses vague and ambiguous terminology, which could open the door to a range of legal disputes and tie up disputants in courts for years, another dynamic that could significantly throttle the commercialization of innovations that may trace their provenance in some degree to federal R&D funding. Most concerningly, the framework provides no clear definition of what constitutes a “reasonable price.” This suggests that application of a “reasonable price” standard would be arbitrary and likely determined on an “agency-by-agency basis.” This would no doubt constitute the basis for endless wrangling over the standard.

More concerningly, should price become a legitimate basis for the application of Bayh Dole march-in rights, this will undoubtedly lead to a flood of petitions that a great number of products (across many sectors) are priced too high. This will place great burdens on federal agencies, as resources—including staff and time—get reallocated toward adjudicating march-in petitions. This will mean that instead of focusing on core agency missions, or on how federal agencies can truly help support the development and commercialization of technologies in the public benefit, they’ll spend much more of their time and resources adjudicating march-in petitions. The interagency framework proposal asks, “Would march-in have an impact on public availability of the benefit of the invention in the short and long-term?” As this submission argues, not only will “price as a basis for march-in” have an impact on public availability of innovations—because the private sector will be commercializing far fewer technologies arising from federally funded R&D—there will also be fewer innovations because federal agencies will be forced to spend far more of their resources on adjudicating march-in petitions.

Another concern relating to terminology in the proposed framework pertains to the definition of “Practical Application.” The requirement to achieve practical application applies only to the contractor—usually the academic institution licensing the invention—not the licensee—which sets the price.[91]

In March 2023, the NIH rejected the sixth march-in petition for the prostate cancer drug Xtandi (manufactured by the firm Astellas) which had already been denied three times between the Obama and Biden administrations. Importantly, the decision noted the licensor (here, the University of California) not the licensee (here, Astellas) is obliged to meet the practical application requirement.[92] As the NIH concluded:

Astellas, the maker of Xtandi, estimates that more than 200,000 patients were treated with Xtandi from 2012 to 2021. Therefore, the patent owner, the University of California, does not fail the requirement for bringing Xtandi to practical application, as the drug is manufactured and on the market in the manner of other prescription drugs. NIH has reviewed the information submitted by the current petitioners, which is substantially the same as that submitted in 2016, and reached the conclusion that Xtandi is still widely available as a prescription drug.[93]

The Biden Administration’s Many Flawed Rationales for Its Flawed Proposal

It’s perhaps not a surprise that the Biden administration has resorted to a variety of flawed arguments in an attempt to justify such an equally flawed policy proposal. In particular, one of the administration’s justifications for this proposal—the assertion that America’s biopharmaceutical industry is excessively concentrated—is wholly fallacious.[94]

The administration palpitates that America’s 25 largest pharmaceutical companies command around 70 percent of industry revenues.[95] Yet that is hardly evidence of an overconcentrated market. To see one that truly is, just look at the pharmacy benefit managers (PBM) market, where just four companies—Express Scripts, OptumRx, Prime Therapeutics, and Kaiser Pharmacy—commanded 68 percent of the revenue in 2021.[96] That’s a concentrated market; America’s pharmaceutical sector is not.

Moreover, if anything, America’s biopharmaceutical industry has actually gotten less concentrated over time. For instance, in 2006, the top 10 drug producers accounted for 56 percent of global industry sales, while the top 60 accounted for 92 percent. But by 2019, the top 10 accounted for 43 percent, and the top 60 accounted for 86 percent.[97]

Further, looking at combined output for firms in the United States (not imports), using data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2020 Economic Census, the sales for the top four in each industry (the C4 ratio) in the Pharmaceutical Preparation Manufacturing and Biological Product Manufacturing industries (NAICS codes 325412 and 325414) increased only modestly from 2002 to 2017, from 36 percent to 43 percent, while the C8 ratio increased from 54 to 58 percent, and the C20 ratio fell slightly from 77 percent to 76 percent.[98]

Moreover, given that drugs are sold internationally, a more accurate measure of market concentration should take into account all drug firms. In 2019, the top 4 firms globally had just 21 percent of the market, with the top 8 having 37 percent, and the top 20 64 percent. While the C4 and C8 ratios were up slightly from 2006, when they were 18 percent and 31 percent, respectively, the C20 ratio actually fell to 64 percent.

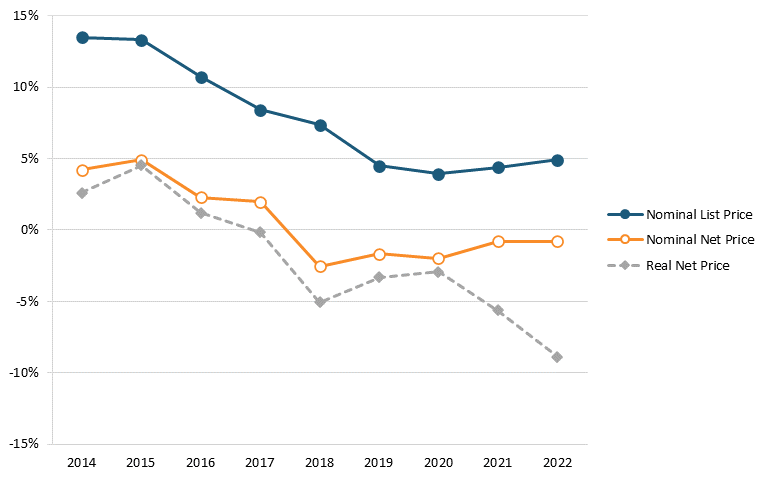

So, the Biden administration is flat wrong that America’s biopharmaceutical industry is excessively concentrated. It’s also flat wrong that U.S. drug prices are rising excessively out of control. For instance, data released by Drug Channels in January 2023 found that, for 2022, brand-name drugs’ net prices dropped for an unprecedented fifth consecutive year and, after adjusting for overall inflation, brand-name drug net prices plunged by almost 9 percent in 2022. In fact, Drug Channels’ Adam Fein has found that the growth in both list and net prices for drugs decreased from 2014 to 2021 and that net prices actually fell each year between 2018 and 2022. Specifically, the year-over-year growth rate in list prices fell from 13.4 percent in 2014 to 4.3 percent in 2021, and the year-over-year growth rate in net prices fell from 4.6 percent to -1.2 percent.[99] (See figure 3.) Furthermore, a recent report from the IQVIA Institute found, “Net manufacturer prices—the cost of medicines after all discounts and rebates have been paid—were unchanged in 2022 and continued below inflation for the fifth year.”[100]

Figure 3: Change in average list and net prices of brand-name drugs, 2014–2021[101]

The IQVIA Institute report also noted that, “Overall U.S. annual average inflation increased sharpy in 2021 and remains high, but net price growth for drugs is notably not following the same patterns in the wider economy.”[102] This dispels the canard that some drug price control advocates have asserted that drug prices have been a key driver of the spiraling inflation rates that have gripped the United States in recent years. For instance, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), over the 12-month period from May 2021 to May 2022, U.S. consumer prices for all goods increased by 8.6 percent, while prescription drug prices rose only 1.9 percent.[103]

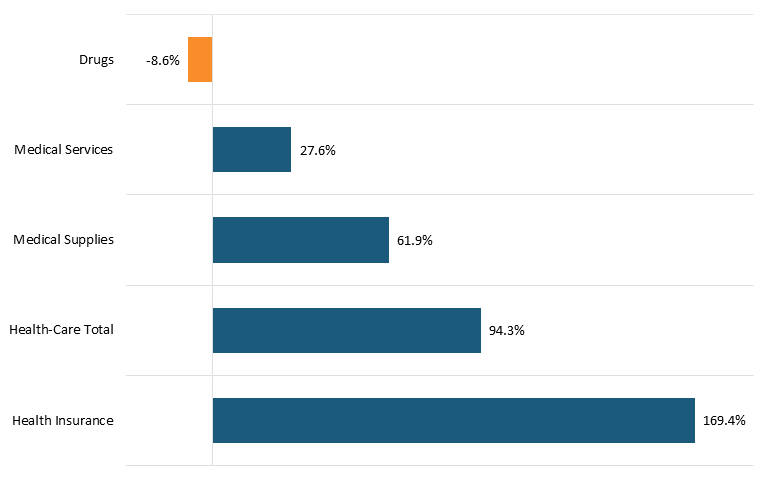

Nor is this recent trend unique. In fact, as calculated by BLS Statistics, from 2005 to 2020, Americans’ reported expenditures on health insurance increased by over 160 percent while their total healthcare expenditures increased 94 percent, but consumer expenditures on drugs actually fell by almost 9 percent over that period.[104] (See figure 4.) This does not necessarily mean overall drug expenditures fell, because health insurance and hospitals also purchase drugs, but it does address consumers’ out-of-pocket costs.

Figure 4: Percent change in consumers’ reported health-care expenditures, 2005–2020[105]

In short, trying to control drug prices represents a very weak rationale for upending over 40 years of established and effective practice regarding the Bayh-Dole Act.

Conclusion

America’s innovation system is fragile, and its leadership in advanced technology industries is never guaranteed or assured. As ITIF wrote in a 2021 report, “Going, Going, Gone? To Stay Competitive in Biopharmaceuticals, America Must Learn From Its Semiconductor Mistakes,” “Taking the [biopharmaceuticals] industry for granted and believing that government can impose regulations with no harmful effect—common policy views in Washington—will almost certainly mean passing the torch of global leadership to other nations, especially China, within a decade or two.”[106] Indeed, the United States has taken—only to sacrifice—its lead in a wide-range of advanced technology industries, including semiconductors, telecommunications equipment, televisions, solar panels, and chemicals, often in part because of significant policy lapses.[107]

In conclusion, it’s worth recollecting what The Economist wrote about the Bayh-Dole in 2002, about 20 years after the Act’s passage. The Bayh-Dole Act was:

Possibly the most inspired piece of legislation to be enacted in America over the past half-century. Together with amendments in 1984 and augmentation in 1986, this unlocked all the inventions and discoveries that had been made in laboratories throughout the United States with the help of taxpayers’ money. More than anything, this single policy measure helped to reverse America’s precipitous slide into industrial irrelevance.[108]

It's perhaps worth imagining what The Economist will write about the Biden administration’s 2024 march-in guidance in another 20 years, in 2044. It was:

Perhaps the most ill-advised regulatory change to be introduced by a U.S. agency over the past half-century. It severely undermined America’s successful technology transfer and commercialization system, particularly throttling academic transfer of technologies stemming from federally funded R&D, locking back up on university shelves discoveries that had been made in laboratories throughout the United States with the help of taxpayers’ money, all while precluding the formation of thousands of startups. The decision came on the heels of the 2022 passage of the CHIPS and Science Act, which pumped tens of billions into America’s science and innovation enterprise and was at the time heralded as a watershed moment to restore U.S. competitiveness, but the decision vitiated much of the Act’s impact. Indeed, the Act’s investments had done little to stimulate new waves of startups; deprived of their feedstock, the SBIR and regional tech hubs programs foundered; and academic technology transfer offices and staff at many American universities had shriveled as licensing activity dried up. More than anything, this single policy measure accelerated America’s precipitous slide into industrial irrelevance, economic drift, and continued loss of leadership in advanced technology industries that organizations like ITIF had already extensively documented as early as its 2023 Hamilton Index report.[109]

The Bayh-Dole Act has proven one of the most successful and effective pieces of legislation in U.S. history. It is working extremely well and is not in need of significant changes. The Draft Interagency Guidance Framework for Considering the Exercise of March-In Rights should be withdrawn immediately.

Thank you for your consideration and the opportunity to comment.

Endnotes

[1]. Department of Commerce, National Institute for Standards and Technology (NIST), “Request for Information Regarding the Draft Interagency Framework for Considering the Exercise of March-in Rights,” Federal Register Vol. 88, No. 235 (December 8, 2023), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2023-12-08/pdf/2023-26930.pdf.

[2]. Joe Kennedy, “How to Ensure That America’s Life-sciences Sector Remains Globally Competitive” (ITIF, March 2018), 37, https://itif.org/publications/2018/03/26/how-ensure-americas-life-sciences-sector-remains-globally-competitive; European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations (EFPIA), “The Pharmaceutical Industry in Figures, Key Data 2017,” 8, https://www.efpia.eu/media/219735/efpia-pharmafigures2017_statisticbroch_v04-final.pdf.

[3]. Justin Chakma et al., “Asia���s Ascent—Global Trends in Biomedical R&D Expenditures” New England Journal of Medicine 370, No. 1 (January 2014); ER Dorsey et al., “Funding of US Biomedical Research, 2003-2008” New England Journal of Medicine 303 (2010): 137–43, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20068207.

[4]. Neil Turner, “What’s gone wrong with the European pharmaceutical industry,” Thepharmaletter, April 29, 1999, https://www.thepharmaletter.com/article/what-s-gone-wrong-with-the-european-pharmaceutical-industry-by-neil-turner; David Michels and Aimison Jonnard, “Review of Global Competitiveness in the Pharmaceutical Industry” (U.S. International Trade Commission, 1999), 2-3, https://www.usitc.gov/publications/332/pub3172.pdf.

[5]. John K. Jenkins, M.D., “CDER New Drug Review: 2015 Update” (PowerPoint presentation, U.S. Food and Drug Administration/CMS Summit, Washington, D.C., December 14, 2015).

[6]. Jenkins, “CDER New Drug Review,” 23; Ian Lloyd, “Pharma R&D Annual Review 2020 NAS Supplement,” PharmaIntelligence, April 2020.

[7] Robert D. Atkinson, “Why Life-Sciences Innovation Is Politically “Purple”— and How Partisans Get It Wrong” (ITIF, February 2016), https://www2.itif.org/2016-life-sciences-purple.pdf.

[8]. B. Graham, “Patent Bill Seeks Shift to Bolster Innovation,” The Washington Post, April 8, 1978; Ashley J. Stevens et al., “The Role of Public-Sector Research in the Discovery of Drugs and Vaccines,” The New England Journal of Medicine Vol. 364:6 (February 2011): 1, https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMsa1008268.

[9]. Naomi Hausman, “University Innovation, Local Economic Growth, and Entrepreneurship,” U.S. Census Bureau Center for Economic Studies Paper No. CES-WP- 12–10 (July 2012): 5, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2097842.

[10]. Louis G. Tornatzky and Elaine C. Rideout, “Innovation U 2.0: Reinventing University Roles in a Knowledge Economy” (State Science and Technology Institute, 2014) 165, https://ssti.org/report-archive/innovationu20.pdf.

[11]. Joseph P. Allen, “When Government Tried March In Rights to Control Health Care Costs,” IPWatchdog, May 2, 2016, http://www.ipwatchdog.com/2016/05/02/march-in-rights-health-care-costs/id=68816/.

[12]. Statement of Elmer B. Staats, comptroller general of the United States, Before the Committee on the Judiciary United States Senate, “S. 414-The University and Small Business Patent Procedures Act,” May 16, 1979, https://www.gao.gov/assets/100/99067.pdf.

[13]. David Mowery, “University-Industry Collaboration and Technology Transfer in Hong Kong and Knowledge-based Economic Growth,” (working paper, University of California, Berkeley, 2009), http://www.savantas.org/cmsimg/files/Research/HKIP/Report/1_mowery.pdf.

[14]. “Innovation’s Golden Goose,” The Economist, December 12, 2002, http://www.economist.com/node/1476653.

[15]. Wendy H. Schacht, “Patent Ownership and Federal Research and Development (R&D): A Discussion of the Bayh-Dole Act and the Stevenson-Wydler Act” (Congressional Research Service, 2000), http://ncseonline.org/nle/crsreports/science/st-66.cfm.

[16]. Hausman, “University Innovation, Local Economic Growth, and Entrepreneurship,” 7. (Calculation based on NBER patent data.)

[17]. John H. Rabitschek and Norman J. Latker, “Reasonable Pricing—A New Twist for March-in Rights Under the Bayh-Dole Act” Santa Clara High Technology Law Journal Vol. 22, Issue 1 (2005), 150, https://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1399&context=chtlj; The Economist, “Innovation’s Golden Goose.”

[18]. AUTM, “Driving the Innovation Economy: Academic Technology Transfer in Numbers (2022),” https://autm.net/AUTM/media/Surveys-Tools/Documents/AUTM-Infographic-22-for-uploading.pdf.

[19]. Ibid.

[20]. Ibid.

[21]. Phone interview with Joe Allen, July 24, 2018.

[22]. Hausman, “University Innovation, Local Economic Growth, and Entrepreneurship,” 8.

[23]. Ibid.

[24]. Saul Lach and Mark Schankerman, “Incentives and Invention in Universities,” RAND Journal of Economics Vol 39, No. 2 (2008): 403–433, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/j.0741-6261.2008.00020.x.

[25]. Scott Shane, “Encouraging University Entrepreneurship? The Effect of the Bayh-Dole Act on University Patenting in the United States” Journal of Business Venturing 19 (2004): 127–151, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1495504.

[26]. Robert D. Atkinson, “Understanding the U.S. National Innovation System, 2020” (ITIF, November 2020), https://itif.org/publications/2020/11/02/understanding-us-national-innovation-system-2020/.

[27]. Innovators Legal, “The SBIR and STTR Extension Act of 2022 – What You Need to Know,” October 11, 2022, https://innovators.legal/the-sbir-and-sttr-extension-act-of-2022-what-you-need-to-know/.

[28]. Fred Block and Matthew Keller, “Where Do Innovations Come From? Transformations in the U.S. National Innovation System, 1970-2006” (ITIF, July 2008), 15, http://www.itif.org/files/Where_do_innovations_come_from.pdf.

[29]. Robin Gaster, “Impacts of the SBIR/STTR Programs: Summary and Analysis,” (Incumetrics, May 2017), 2-4, https://sbtc.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Impacts-of-the-SBIR-program.pdf.

[30]. Stephen Ezell, “Testimony Before the Committee on Small Business and Entrepreneurship, Hearing on Reauthorization of the SBA’s Innovation Programs” (ITIF, May 2019), https://itif.org/publications/2019/05/15/testimony-senate-small-business-and-entrepreneurship-committee-reauthorizing/.

[31]. Robert D. Atkinson, Stephen J. Ezell, and Luke A. Stewart, “The Global Innovation Policy Index” (ITIF and the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation, March 2012), 65, https://www2.itif.org/2012-global-innovation-policy-index.pdf.

[32]. California Senate Office of Research, “Optimizing Benefits From State-Funded Research” Policy Matters (March 2018), 12, https://sor.senate.ca.gov/sites/sor.senate.ca.gov/files/0842%20policy%20matters%20Research%2003.18%20Final.pdf.

[33]. Rabitschek and Latker, “Reasonable Pricing,” 150.

[34]. John R. Thomas, “March-In Rights Under the Bayh-Dole Act” (Congressional Research Service, August 2016), 7, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R44597.pdf.

[35]. David S. Bloch, “Alternatives to March-In Rights” Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment and Technology Law, Vol. 18:2:247 (2016): 253, http://www.jetlaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Bloch_SPE_6-FINAL.pdf.

[36]. Statement of Senator Birch Bayh to the National Institutes of Health (May 24, 2004), https://www.ott.nih.gov/sites/default/files/documents/2004NorvirMtg/2004NorvirMtg.pdf.

[37]. Stephen Ezell, “No, America’s Drug Prices Aren’t Climbing Radically Out of Control,” The Innovation Files, June 17, 2022, https://itif.org/publications/2022/06/17/no-americas-drug-prices-arent-climbing-radically-out-of-control/.

[38]. Thomas, “March-In Rights Under the Bayh-Dole Act,” 11.

[39]. Ibid, 14.

[40]. Joseph Allen, “Proposal from Senator King Won’t Reduce Drug Prices, Just Innovation,” IPWatchdog, July 17, 2017, https://www.ipwatchdog.com/2017/07/17/senator-king-reduce-drug-prices-innovation/id=85702/.

[41]. Thomas, “March-In Rights Under the Bayh-Dole Act,” 10.

[42]. Birch Bayh, “Statement of Birch Bayh to the National Institutes of Health,” May 25, 2014, http://www.essentialinventions.org/drug/nih05252004/birchbayh.pdf.

[43]. Birch Bayh and Bob Dole, “Our Law Helps Patients Get New Drugs Sooner,” The Washington Post, April 11, 2002, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/opinions/2002/04/11/our-law-helps-patients-get-new-drugs-sooner/d814d22a-6e63-4f06-8da3-d9698552fa24/?utm_term=.ddbf6876a380.

[44]. Ibid.

[45]. Allen, “When Government Tried March In Rights to Control Health Care Costs.”

[46]. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), “Return on Investment Initiative: Draft Green Paper” (NIST, December 2018), 30, https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/SpecialPublications/NIST.SP.1234.pdf.

[47]. Ibid, 30.

[48]. Thomas, “March-In Rights Under the Bayh-Dole Act,” 9.

[49]. Ibid.

[50]. Ibid.

[51]. Ibid., 11–12.

[52]. Elias A. Zerhouni, director, NIH, “In the Case of Norvir Manufactured by Abbott Laboratories, Inc.,” July 29, 2004, http://www.ott.nih.gov/sites/default/files/documents/policy/March-In-Norvir.pdf.

[53]. Rabitschek and Latker, “Reasonable Pricing,” 160.

[54]. Ibid, 167.

[55]. Peter Amo and Michael Davis, “Why Don’t We Enforce Existing Drug Price Controls? The Unrecognized and Unenforced Reasonable Pricing Requirements Imposed upon Patents Deriving in Whole or in Part from Federally Funded Research,” Tulane Law Review Vol. 75, 631 (2001), https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1754&context=fac_articles.

[56]. Ibid.

[57]. Rabitschek and Latker, “Reasonable Pricing,” 162–163.

[58]. Ibid, 163.

[59]. Ibid. Here, the Presidential Memoranda refers to memoranda produced by the Kennedy and Nixon administrations that pertained to government policy related to contractor ownership of inventions.

[60]. Ibid.

[61]. Stephen Ezell interview with Joseph P. Allen, November 18, 2018.

[62]. U.S. DoC NIST, “Request for Information Regarding the Draft Interagency Framework for Considering the Exercise of March-in Rights.”

[63]. Ibid.

[64]. Stephen J. Ezell, “Why Exploiting Bayh-Dole ‘March-In’ Provisions Would Harm Medical Discovery,” The Innovation Files, April 29, 2016, https://www.innovationfiles.org/why-exploiting-bayh-dole-march-in-provisions-would-harm-medical-discovery/.

[65]. Bloch, “Alternatives to March-In Rights,” 261.

[66]. Ibid.

[67]. U.S. DoC NIST, “Request for Information Regarding the Draft Interagency Framework for Considering the Exercise of March-in Rights.”

[68]. AUTM, “Better World Project,” https://autm.net/about-tech-transfer/better-world-project/about-better-world.

[69]. Congressional Budget Office (CBO), “Research and Development in the Pharmaceutical Industry”(CBO, April 2021), https://www.cbo.gov/publication/57126.

[70]. Trelysa Long, “Preserving U.S. Biopharma Leadership: Why Small, Research-Intensive Firms Matter in the U.S. Innovation Ecosystem” (ITIF, August 2023), 1, https://itif.org/publications/2023/08/21/preserving-us-biopharma-leadership-why-small-research-intensive-firms-matter/.

[71]. National Institutes of Health, “NIH News Release Rescinding Reasonable Pricing Clause,” news release, April 11, 1995, https://www.ott.nih.gov/sites/default/files/documents/pdfs/NIH-Notice-Rescinding-Reasonable-Pricing-Clause.pdf.

[72]. Ibid.

[73]. Allen, “Compulsory Licensing for Medicare Drugs—Another Bad Idea from Capitol Hill.”

[74]. National Institutes of Health, “OTT Statistics,” accessed January 13, 2019, https://www.ott.nih.gov/reportsstats/ott-statistics.

[75]. National Institutes of Health, “NIH News Release Rescinding Reasonable Pricing Clause.”

[76]. Allen, “Compulsory Licensing for Medicare Drugs—Another Bad Idea from Capitol Hill.”

[77]. California Senate Office of Research, “Optimizing Benefits From State-Funded Research,” 11.

[78]. Eric Sagonowsky, “Sanofi Pulls Out of Zika Vaccine Collaboration as Feds Gut its R&D Contract,” FiercePhrma, September 1, 2017, https://www.fiercepharma.com/vaccines/contract-revamp-sanofi-s-Zika-collab-u-s-government-to-wind-down; Ed Silverman, “Sanofi Rejects U.S. Army Request for ‘Fair” Pricing’ for a Zika Vaccine,” PBS, May 20, 2017, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/health/sanofi-army-request-pricing-Zika-vaccine.

[79]. Bernie Sanders, “Trump Should Avoid a Bad Zika Deal,” The New York Times, March 10, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/10/opinion/bernie-sanders-trump-should-avoid-a-bad-Zika-deal.html?_r=0.

[80]. Eric Sagonowsky, “Sanofi Executive Lays Out Case For Taxpayer Funding—And Exclusive Licensing—on Zika Vaccine R&D,” FiercePhrma, May 25, 2017, https://www.fiercepharma.com/vaccines/exec-says-corporate-responsibility-not-potential-profits-drove-sanofi-s-Zika-vaccine-r-d.

[81]. Jeannie Baumann, “Sanofi Never Rejected Fair Pricing for Zika Vaccine: Exec,”BloombergNews, July 18, 2017, https://www.bna.com/sanofi-rejected-fair-n73014461930/.

[82]. Sagonowsky, “Sanofi Executive Lays Out Case For Taxpayer Funding—And Exclusive Licensing—on Zika Vaccine R&D.”

[83]. Sagonowsky, “Sanofi Pulls Out of Zika Vaccine Collaboration as Feds Gut its R&D Contract.”

[84]. Joseph Allen, “Bayh-Dole Under March-in Assault: Can It Hold Out?” IP Watchdog, January 21, 2016, http://www.ipwatchdog.com/2016/01/21/bayh-dole-under-march-in-assault-can-it-hold-out/id=65118/.

[85]. AUTM, “Driving the Innovation Economy.”

[86]. The White House, “FACT SHEET: Biden-Harris Administration Announces New Actions to Lower Health Care and Prescription Drug Costs by Promoting Competition,” news release, December 7, 2023, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2023/12/07/fact-sheet-biden-harris-administration-announces-new-actions-to-lower-health-care-and-prescription-drug-costs-by-promoting-competition/.

[87]. Vital Transformation, “New study finds 92% of new approved medicines have no federally funded intellectual property or patents,” news release, November 30, 2023, https://vitaltransformation.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/FINAL-march-in-press-release-30Nov2023-1.pdf.

[88]. Gwen O’Loughlin and Duane Schulthess, “March-in rights under the Bayh-Dole Act & NIH contributions to pharmaceutical patents” (Vital Transformation, November 30, 2023), https://vitaltransformation.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/march-in_v11_BIO-approved-30Nov2023.pdf.

[89]. Vital Transformation, “New study finds 92% of new approved medicines have no federally funded intellectual property or patents.”

[90]. Ibid.

[91]. Bayh-Dole Coalition, “Bayh-Dole Coalition Comments on NIST Draft March-in Framework,” January 17, 2024, 4, https://bayhdolecoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Bayh-Dole-Coalition-Comments-on-NIST-Draft-March-in-Framework-2.pdf.

[92]. Ibid.

[93]. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, “Reply Letter to Robert Sachs and Clare Love, Re: Xtandi March-in Petition,” https://www.keionline.org/wp-content/uploads/NIH-rejection-Xtandi-marchin-21march2023.pdf.

[94]. Stephen Ezell, “Biden’s Assertion of Excessive Biopharma Industry Concentration Is a Flawed Rationale for a Flawed Policy,” Innovation Files, December 11, 2023, https://itif.org/publications/2023/12/11/biopharma-concentration-is-a-flawed-rationale-for-a-flawed-policy/.

[95]. The White House, “FACT SHEET: Biden-Harris Administration Announces New Actions to Lower Health Care and Prescription Drug Costs by Promoting Competition.”

[96]. Marc Iskowitz, “AMA analysis of PBM markets finds competition decline among drug middlemen,” Medical Marketing & Media, September 15, 2023, https://www.mmm-online.com/home/channel/ama-analysis-of-pbm-markets-finds-competition-decline-among-drug-middlemen/.

[97]. Robert D. Atkinson and Stephen Ezell, “Five Fatal Flaws in Rep. Katie Porter’s Indictment of the U.S. Drug Industry” (ITIF, May 2021), https://itif.org/publications/2021/05/20/five-fatal-flaws-rep-katie-porters-indictment-us-drug-industry/.

[98]. United States Census Bureau, 2002 Economic Census Tables (accessed May 11, 2021), https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2002/econ/census/manufacturing-reports.html; United States Census Bureau, 2017 Economic Census Tables (accessed May 11, 2021), https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2017/econ/economic-census/naics-sector-31-33.html.

[99]. Adam Fein, “Brand-Name Drug Prices Fell for the Fifth Consecutive Year—And Plummeted After Adjusting for Inflation,” Drug Channels, January 4, 2023, https://www.drugchannels.net/2023/01/brand-name-drug-prices-fell-for-fifth.html.

[100]. IQVIA Institute, “The Use of Medicines in the U.S. 2023: Usage and Spending Trends and Outlook to 2027,” (IQVIA Institute, April 2023), 35, https://www.iqvia.com/insights/the-iqvia-institute/reports/the-use-of-medicines-in-the-us-2023.

[101]. Fein, “Brand-Name Drug Prices Fell for the Fifth Consecutive Year.”

[102]. Ibid.

[103]. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Consumer Price Index,” (accessed June 10, 2022), https://www.bls.gov/cpi/.

[104]. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Expenditure Survey (Healthcare expenditures, 2005-2020) https://www.bls.gov/cex/.

[105]. Ibid.

[106]. Stephen Ezell, “Going, Going, Gone? To Stay Competitive in Biopharmaceuticals, America Must Learn From Its Semiconductor Mistakes” (ITIF, November 2021), https://itif.org/publications/2021/11/22/going-going-gone-stay-competitive-biopharmaceuticals-america-must-learn-its/

[107]. Sandra Barbosu, “Not Again: Why the U.S. Can’t Lose Its Biopharmaceutical Industry” (ITIF, Forthcoming, March 2024).

[108]. “Innovation’s Golden Goose,” The Economist.

[109]. Robert D. Atkinson and Ian Tufts, “The Hamilton Index, 2023: China Is Running Away With Strategic Industries” (ITIF, December 2023), https://itif.org/publications/2023/12/13/2023-hamilton-index/.

Editors’ Recommendations

November 22, 2021

Going, Going, Gone? To Stay Competitive in Biopharmaceuticals, America Must Learn From Its Semiconductor Mistakes

February 22, 2016

Why Life-Sciences Innovation Is Politically “Purple”— and How Partisans Get It Wrong

November 2, 2020