How to Address Political Speech on Social Media in the United States

Policymakers could improve content moderation on social media by building international consensus on content moderation guidelines, providing more resources to address state-sponsored disinformation, and increasing transparency in content moderation decisions.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Key Takeaways

Contents

The Debate Over Content Moderation on Social Media. 4

Crowdsourced Content Moderation. 12

Industry-Developed Best Practices 13

First Amendment Reinterpretation. 17

Regulations on Algorithms and Targeted Advertising. 18

Data Portability and Interoperability Requirements 19

Government-Run Social Media Platform. 24

Commissions, Boards, and Councils 25

Introduction

The primary reason the debate over how to regulate large social media companies’ content moderation policies and practices has become so polarized and intractable in the United States is the political Left and Right do not agree on the problem. Many conservatives believe that large social media companies have a liberal bias and censor conservative users and viewpoints, unfairly using their market power to advance a liberal agenda and promote a “cancel culture.” In contrast, many liberals believe that large social media companies insufficiently police hate speech, election disinformation, and other dangerous speech they believe undermines democracy. So while liberals are demanding social media companies more zealously take down content and deplatform users, conservatives are pushing for these same companies to show more restraint and prudence in their content moderation policies. In the end, both sides blame large social media companies, but offer little in terms of bipartisan consensus on how to move forward.

Social media companies face a no-win scenario: Policymakers have placed the onus on them to address complex content moderation questions, but then attack them when they do. When they remove controversial content, critics say they are eroding free speech; and when they allow that content to remain, critics say they are spreading misinformation and undermining democracy. The January 6 insurrection provides an illustrative example. One side blames social media companies for failing to act sooner against users sharing false allegations of a stolen election, while the other argues these companies overreacted by banning a sitting U.S. president from their platforms along with his supporters.[1]

As detailed in this report, there have been multiple proposals put forth to address this issue—usually by shifting more responsibility for content moderation on industry, users, or government—but all fall short for one reason or another. Therefore, a new approach is necessary to overcome this impasse. To create a path forward, the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) recommends the following:

First, the U.S. government should establish an international forum for participants from the Group of Seven (G7) nations to develop voluntary, consensus-based content moderation guidelines for social media based on shared democratic values. The goal would be to create a forum for individuals from businesses, governments, academia, and civil society to exchange insights and perspectives and create guidelines that help social media platforms ensure their content moderation processes prioritize transparency, accountability, and due process while balancing free speech and addressing harmful speech. By leveraging an open multistakeholder process, this international forum could develop best practices that not only positively impact content moderation on social media, but also gain acceptance among policymakers around the world.

Second, the U.S. government should help social media platforms respond to state-sponsored harmful content, such as Russian disinformation and Chinese bots. For example, U.S. government agencies could fund academic research to improve methods for identifying and responding to state-backed disinformation campaigns or develop better information sharing arrangements between government and social media companies about potential threats.

Third, Congress should pass legislation establishing transparency requirements for content moderation decisions of social media platforms. This legislation should require social media platforms to disclose their content moderation policies describing what content and behavior they allow and do not allow, how they enforce these rules, and how users can appeal moderation decisions—disclosures that most large social media platforms already make. Additionally, the law should require platforms to enforce their content moderation policies consistently and create an appeals process for users to challenge content moderation decisions, if one does not already exist. To increase transparency, platforms should publicly release annual reports on their content moderation enforcement actions.

Content moderation suffers from a crisis of legitimacy, and social media companies cannot resolve this issue on their own. There will always be people who disagree on specific content moderation policies or castigate social media companies for their role in enforcing these policies. However, by building international consensus on content moderation guidelines, providing more resources to address state-sponsored misinformation and disinformation, and increasing transparency in content moderation decisions, policymakers can address the most serious problems and offer social media platforms best practices that balance competing interests.

The Debate Over Content Moderation on Social Media

To paraphrase Bill Gates, the Internet has become the town square of a global village.[2] Before the Internet, the primary ways individuals could broadcast their unfiltered views were expensive and time consuming and had limited reach, such as by mailing newsletters, distributing flyers, placing posters in public places, or shouting from the street corner. The rise of user-generated content—especially blogs, podcasts, and social media platforms—has not only lowered the cost of direct communication, but has empowered anyone on the Internet to bypass traditional gatekeepers, such as print and broadcast news media, and make their views available to everyone else online. This development is exciting and transformative but has also brought new challenges with these new opportunities.

The promise and peril of social media in particular has become a focus of heated debate because it is the communication platform on which users wage ideological battles, campaign for elections, and strive to win hearts and minds during wars and revolutions. And unlike the town squares of the past, which fell directly under the jurisdiction of government, today’s digital town squares are owned and operated by private corporations. This change raises new questions about not only governance and regulation, but also the future of free speech.

While both the Internet and social media will continue to evolve, the technology has given voice to millions of users worldwide—and that genie cannot be put back in the bottle. Therefore, the task ahead is how to establish a governance system for social media that matches the nature of the medium. One of the biggest challenges is content moderation on social media.

This report provides an analysis of the various proposed solutions to improve content moderation of political speech on large social media platforms. “Political speech” refers not only to speech by political officials or about politics (including political ads) but any noncommercial speech protected by the First Amendment that involves matters of public concern. This definition encompasses a broad variety of speech on social media, from posts by government officials and those running for office to commentary about political issues from ordinary citizens. Naturally, this definition excludes commercial speech (e.g., advertising to promote business interests), as well as various types of unprotected speech, including obscenities, defamation, fraud, or incitement to violence.

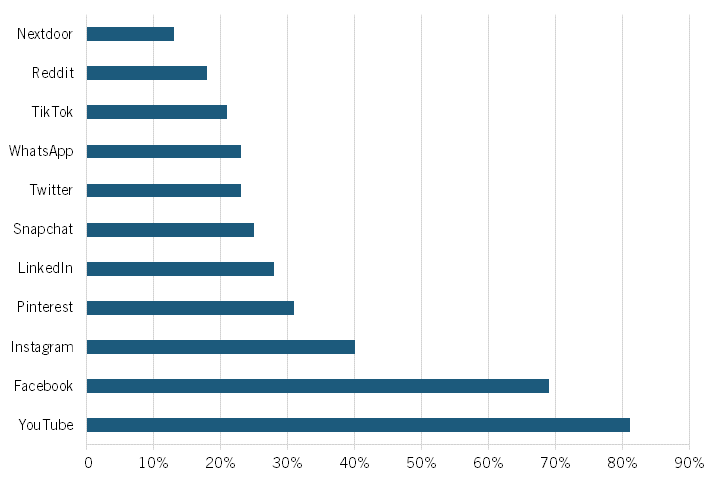

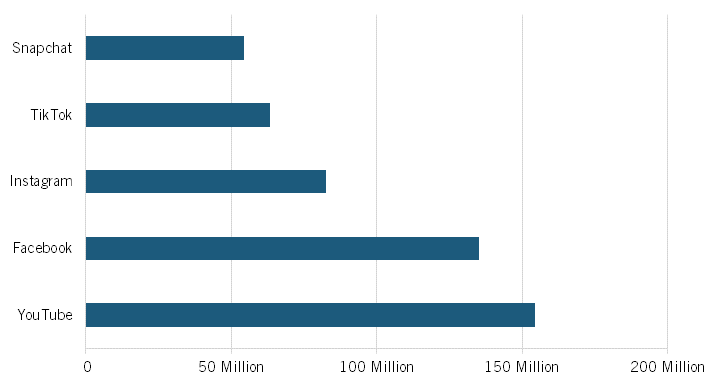

This report mostly considers the impact of proposals on the largest social media companies because they have been the primary focus of policymakers. However, the definition of “large” is subjective. The largest social media platforms globally include a number with over a billion active users, including Facebook, YouTube, WhatsApp, Instagram, WeChat, and TikTok. But many others also include hundreds of millions of active users worldwide, including QQ, Weibo, Telegram, Snapchat, Kuaishou, Pinterest, Twitter, and Reddit, and could hardly be called small.[3] Alternatively, policymakers could only target policies at social media companies based on the number of domestic users, and in the United States, there are a handful with over 10 million active monthly users that could be added to this list, including Reddit, Snapchat, and Discord (see figure 1 and figure 2).[4] In addition, if the goal is to impact influential platforms, policymakers should not ignore small and medium-sized social media platforms, including emerging ones, such as Gettr, Parler, Gab, and Truth Social. Although these platforms do not have as many users as larger ones do, prominent users on these platforms may still have a significant reach across these social networks.

Figure 1: Percentages of U.S. adults who use popular social media apps (Pew Research Center, 2021)[5]

Figure 2: Total unique U.S. adult mobile users of popular social media apps (ComScore, November 2021)

Finding common ground on moderating political speech is difficult because there are a number of areas of disagreement beyond the question of whether social media platforms should be removing more or less content. While many of these disagreements break down along party lines, others reflect other ideological disagreements, often about the role of government in regulating private companies:

▪ Should social media platforms prioritize protecting free speech, or should they prevent the spread of misinformation, harmful content, and objectionable material?

▪ Should social media platforms be politically neutral, or should they be allowed to have their own political biases?

▪ Should social media platforms set their own content moderation policies, or should someone else have this authority?

▪ Should social media platforms treat all users the same, or should certain users, such as elected officials, have special privileges?

▪ Should social media platforms be required to enforce their rules consistently, or should they be allowed to act arbitrarily?

▪ Should social media platforms be transparent about content moderation decisions, or should they be allowed to make decisions privately?

▪ Should social media platforms operate closed ecosystems, or should they be forced to be interoperable with other platforms?

▪ Should social media platforms be liable for harmful third-party content, or should those who produce that content be responsible?

Summary of Proposals

There have been a number of proposals for how to address political speech on social media, which generally fall into the following categories:

▪ Free market solutions: These proposals focus on minimal government intervention and instead rely on industry to address the issues as they see fit.

▪ Rule changes: These proposals involve legislative or regulatory changes that would impact how social media companies could do business, such as requiring platforms to offer equal access to their platform to all political candidates.

▪ Technical reforms: These proposals focus on incentives or requirements for companies to make technical reforms to their algorithms or services.

▪ Structural changes: These proposals would involve extensive government intervention to change the way social media operates on a structural level, such as by breaking up or nationalizing large social media companies.

▪ Commissions, boards, and councils: These proposals focus on building a consensus on what the problems are with the current state of online political speech and creating best practices companies can use for guidance in dealing with those problems that balance concerns over freedom of speech and harmful content.

Table 1: Summary of proposals to address political speech on social media

|

Proposal |

Description |

Pros |

Cons |

|

Free Market Solutions |

|||

|

Status Quo |

Maintain the status quo, with no additional government regulation and no industry-wide coordination. |

▪ Companies may best understand their users’ preferences ▪ Companies may respond to market forces |

▪ Companies still bear responsibility and blame ▪ Other countries may regulate online speech in the absence of U.S. government leadership ▪ Market forces alone are not always effective |

|

Crowdsourced Content Moderation |

Crowdsource content moderation decisions to social media platforms users. |

▪ Decisions are in the hands of users instead of companies or government |

▪ Requires many users to volunteer their efforts ▪ No guarantee that users will make the “right” decisions |

|

Industry-Coordinated Best Practices |

Develop a set of industry-wide best practices for moderating political speech among major social media platforms. |

▪ Companies share best practices ▪ Unified approach to content moderation problems |

▪ Fewer options for users seeking alternative content moderation policies ▪ Companies still bear blame for failures |

|

Rule Changes |

|||

|

Transparency Requirements |

Require social media platforms to be more transparent in their content moderation. |

▪ Companies must adhere to their own standards consistently |

▪ Effectiveness depends on specific requirements ▪ Certain requirements could do more harm than good |

|

Equal Time Rule |

Require social media companies to give political candidates equal access to political and targeted advertising on their platforms regardless of party. |

▪ Solves some problems related to targeted political advertising |

▪ Doesn’t affect political content that isn’t advertising ▪ Doesn’t address disinformation from other sources |

|

First Amendment Reinterpretation |

Reinterpret the First Amendment to apply the same limitations to social media platforms that currently apply to government actors. |

▪ Eliminates concerns about censoring or deplatforming users |

▪ Requires courts to ignore decades of precedent ▪ Implicates other First Amendment jurisprudence ▪ Protects harmful free speech |

|

Regulations on Algorithms and Targeted Advertising |

Impose regulations on social media algorithms and targeted advertising. |

▪ Addresses concern that algorithms amplify harmful content ▪ Companies have less incentive to keep users on the platform without targeted ads |

▪ Algorithms benefit users ▪ Targeted ads allow for free services ▪ Targeted ads benefit businesses |

|

Technical Reforms |

|||

|

Data Portability and Interoperability Requirements |

Require large social media platforms to adhere to data portability and interoperability requirements. |

▪ Easier for users to switch platforms if they’re dissatisfied with content moderation decisions |

▪ Could limit platforms’ ability to moderate effectively ▪ Harder to restrict bot accounts, leading to high rates of spam ▪ Technical challenges in implementation |

|

Public Funding |

Government provides funding for companies to improve their algorithms. |

▪ Government would provide funding for better algorithms |

▪ Doesn’t solve the lack of consensus ▪ Big companies have money to spend on algorithms and these are the companies that have met the most scrutiny |

|

Structural Changes |

|||

|

Antitrust |

Break up the social media companies that host the majority of online speech. |

▪ Would limit ability of any one platform to significantly influence politics and elections ▪ More platforms could provide users more choice with regard to content moderation practices |

▪ Network effects in social media naturally lead to large platforms ▪ Bigness is not an antitrust violation ▪ Smaller platforms would have fewer resources to moderate content ▪ Smaller platforms could contribute to polarization |

|

“Common Carrier” Regulation |

Require social media platforms to “carry” all legal speech. |

▪ No censorship or deplatforming |

▪ Much harmful speech is protected speech |

|

Nationalization |

Nationalize the largest social media companies. |

▪ No private sector decisions about content moderation |

▪ Much harmful speech is protected speech ▪ Government-owned platforms less likely to innovate ▪ Likely would be overturned by courts |

|

Government-Run Social Media Platform |

Government creates its own social media platform. |

▪ No private-sector censorship |

▪ Much harmful speech is protected speech ▪ Government may not be able to compete with private sector ▪ Government-run platform could still be biased |

|

Commissions, Boards, Councils, and Forums |

|||

|

Company Oversight Boards |

Create boards that make binding decisions about individual companies’ content moderation policies and decisions. |

▪ Companies not directly responsible for content moderation decisions |

▪ Public may doubt independence and legitimacy |

|

Company Advisory Councils |

Companies form advisory councils that provide voluntary guidance and feedback on content moderation decisions. |

▪ Companies have outside input on content moderation policies and decisions |

▪ Companies still responsible for their decisions ▪ Unlikely to increase perceived legitimacy of decisions |

|

National Commission |

Create a national commission to make recommendations for all social media companies that operate in the United States. |

▪ Establishes a consensus ▪ Many companies want societal guidance on what to do ▪ Companies would have someone to “blame” for failures |

▪ Guidelines would be voluntary ▪ Left and Right may not be able to compromise ▪ The debate over online speech is international ▪ Companies would have to adhere to many countries’ guidelines |

|

Multistakeholder Forum |

Create a multistakeholder forum of participants from democratic nations to develop guidelines for social media companies. |

▪ Establishes an international consensus ▪ Fewer conflicting rules |

▪ Social media companies may not follow voluntary guidelines ▪ The U.S. and Europe may not be able to compromise where values do not align |

Free Market Solutions

One category of proposals would involve no government regulation and would instead allow social media platforms to continue to set their own content moderation practices. These proposals include maintaining the status quo, implementing crowdsourced content moderation strategies, and creating industry-led best practices for content moderation. Because these proposals require no government intervention, they avoid questions of constitutionality, but are likely to raise questions of legitimacy among social media’s critics.

Status Quo

One proposal to address the issue of political speech on social media is to maintain the status quo, with no additional government regulation and no industry-wide coordination. Different social media platforms would continue to set their own content moderation policies regarding harmful-but-legal content, with users choosing which platforms to use based on their policies.

The benefit of this is it does not force a one-size-fits-all approach to online political speech. Currently, politicians and stakeholders are far from reaching a consensus on what type of lawful content is harmful and how much of this harmful-but-legal content should be allowed on social media. Forms of harmful or objectionable speech such as hate speech, misinformation and disinformation, and violence are not black and white, and even reasonable people disagree about where to draw the line on what is harmful and what is acceptable free speech.

In the absence of government regulation, market forces can and have motivated social media companies to change their content moderation policies and practices. For example, after Russian-backed disinformation campaigns used social media to attempt to influence the 2016 U.S. presidential election, Facebook implemented a series of changes to prevent deceptive advertising, including by making advertising more transparent, improving enforcement for improper ads, tightening restrictions on ad content, and increasing requirements to confirm the identity of advertisers.[6]

One of critics’ main arguments against maintaining the status quo and allowing social media platforms to continue to set their own policies is, when the dominant platforms make up a substantial portion of online speech—with 1.82 billion daily active users on Facebook and 126 million on Twitter—those platforms’ decisions have wide-reaching effects on the rest of society.[7] Critics argue that Facebook and Twitter have amassed such large user bases that choosing to abandon one or both platforms based on their content moderation decisions would cut people off from an important source of information and avenue for communication.

Facebook and Twitter do have competition, including from more established players such as Reddit and Snapchat—with 52 million and 293 million daily active users, respectively—as well as from newer players such as TikTok, which had 50 million daily active users in the United States in 2020 (and only continues to grow).[8] Additionally, YouTube, another dominant social media platform, has largely avoided political and media scrutiny compared with Facebook and Twitter.[9] Political discourse occurs on all of these platforms, as well as elsewhere online.

Facebook and Twitter also face competition from social media platforms, such as Parler, Gettr, Rumble, and Truth Social, designed to cater to those who believe mainstream platforms unfairly silence conservative voices. However, many of these social media companies have struggled to enact content moderation policies that allow controversial forms of content outside the mainstream. For example, following the January 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol, Apple and Google removed Parler from their respective app stores and Amazon Web Services removed the company from its cloud hosting service.[10] After Parler adjusted its content moderation policies and practices, including by excluding certain objectionable content from its iOS mobile app, Apple allowed the app back on the Apple Store in May 2021.[11] Google allowed the Parler app back in the Google Play Store in September 2022, although before then, Android users could load it from alternative app stores.[12] Similarly, Truth Social, the social media app backed by former president Trump, has found that it must comply with the content moderation standards of app stores if it wants to reach their users.[13] Although these actions are examples of companies exercising their right to freedom of association, they demonstrate the difficulty of establishing a social media platform that allows controversial content.

Different social media platforms have different content moderation policies that reflect their different uses, user bases, and goals. However, there are some forms of content—for example, extremist content—that pose a significant risk of harm to society that social media platforms have historically struggled to effectively address through their content moderation practices.[14] Many companies lack the expertise to effectively address this type of content without guidance, and others, especially the smaller ones, may lack the resources.[15] Additionally, there is a lack of consensus on which content to classify as harmful—as some may think certain content is harmful while others think it is legitimate—as well as the best response, such as allowing counter speech versus removing content.[16]

Some issues are especially complex and consequential, such as how to handle government officials who post harmful content or break companies’ terms of service—and there is no consensus on these issues. There are also questions about due process, such as whether there are sufficient appeals mechanisms when platforms make mistakes enforcing their rules and whether it is appropriate for social media companies to both make and enforce the rules.[17]

Although stakeholders do not agree on how to strike the right balance between reducing harmful content on social media and protecting free speech online, many critics on both sides of the aisle agree that the status quo is not tenable. One risk of maintaining the status quo too long is it may eventually generate enough opposition that lawmakers decide to impose objectionable changes that leave users worse off. For example, Germany passed the controversial Network Enforcement Law (NetzDG) in 2017 requiring social media companies with more than 2 million registered users in the country to respond quickly to online hate speech or face severe fines, a requirement critics say chills free speech online.[18] U.S. lawmakers have proposed a number of controversial laws that would impact content moderation—often with unintended consequences—and have likely generated interest less because of the specifics of the proposals and more due to the mounting frustration that lawmakers should be doing more to address a perceived problem.[19]

Another risk to maintaining the status quo for U.S. policymakers is other countries may enact their own laws and regulations for online political speech that impact not just those within their borders, but also Internet users globally. For example, the EU could unilaterally impose its own set of laws and regulations on the process large social media companies must use to respond to complaints about content moderation that would likely set a global baseline. If the United States intends to play a proactive role in shaping these debates in order to safeguard its national interests and values of free speech and innovation, simply upholding the status quo may not be in its best interests.

Crowdsourced Content Moderation

Another free market approach to online political speech would be for social media platforms to crowdsource their content moderation. Many platforms allow users to report inappropriate content, but users do not make content moderation decisions. In this approach, ordinary users would take part in directly moderating content on a platform, such as by making decisions to remove harmful content, ban users, or add labels to misinformation. Crowdsourced content moderation could either take the place of the platform’s own content moderators or supplement them.

Wikipedia, while not a social network, is perhaps the best-known website that uses crowdsourced content moderation. Since its inception, it has allowed ordinary users to write and edit articles on the site.[20] The platform has community-developed and -enforced policies and guidelines in place that determine permissible content and user behavior.[21] Wikipedia’s content moderation process is not perfect—for example, false information still can slip past its editors and some editors report regular harassment—but using volunteers allows Wikipedia to avoid hiring thousands of writers and editors.[22] The popular social network Reddit, which hosts many different communities, each with their own unique rules, also uses volunteer moderators rather than employees to moderate content on its platform.[23]

Twitter is testing out this approach with its Birdwatch pilot program, which allows regular users to place labels on content containing misinformation and rate each other’s labels. Currently, the labels are not visible for Twitter users who are not part of the program, but if the pilot is successful, Twitter plans to expand it to the main site. The goal is for the Twitter community to be able to react quickly when misinformation starts to spread.[24]

Community moderation could solve one of the problems currently facing social media platforms when it comes to political speech, which is that many people do not trust the social media companies to fairly moderate content. Increasingly, critics of social media have expressed their concerns that a few large companies can control a large portion of online political discourse. Community moderation would take some of that control out of the hands of companies and put it into the hands of ordinary users.

But the approach that has allowed Wikipedia to compile a global encyclopedia of facts and knowledge may not work as well when more subjective forms of content are involved, especially controversial political speech. Indeed, fiery debates and edit wars regularly engulf politically sensitive subjects on Wikipedia.[25] Social media platforms have to either enforce volunteer moderators guidelines, in which case they are still be making important decisions regarding which forms of online political speech are acceptable, or they have to trust their community to make the right decisions as a collective, which could damage online political discourse by drowning out controversial political beliefs.

Crowdsourced content moderation also requires a lot of volunteer time, especially to counter intentional efforts by an active minority of users to overrule the majority. And given the high stakes of controlling content moderation on some large platforms, there could be strong incentives for certain groups to try to gain control of content moderation decisions. Even with these shortcomings, crowdsourced content moderation could be an important tool in social media platforms’ tool kit. However, it is unlikely to solve the larger debate surrounding online political speech.

Industry-Developed Best Practices

The final free market proposal to address political speech on social media would be to encourage the major social media platforms to develop a set of industry-wide best practices for moderating political speech. These best practices would address the most pressing content moderation problems, including how to improve transparency, how to handle government figures posting prohibited content, how to find and remove illegal content most effectively, and how to address harmful-but-legal content. These best practices could also describe various remedies, such as removing, labeling, demonetizing, deprioritizing, or otherwise restricting content or users.

The benefit of a set of industry-wide best practices over social media companies’ current individualized approaches is it would allow companies to take a unified approach to important issues. This is especially important when it comes to harmful and illegal content: If certain platforms take a stricter approach to removing harmful and illegal content than others do, individuals and organizations involved in creating and proliferating that content will flock to the platforms that take a more lax approach. But if all major platforms work together to eliminate forms of harmful and illegal content, creators of that content will have few places to congregate and the content will be less visible to the larger online community.

There are examples of other industries that use self-regulation to protect consumers without involving the government. For instance, the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA), a trade association representing major film studios, established its ratings system in 1968 to inform parents on whether a film might be appropriate for children of various ages.[26] In the legal field, the American Bar Association (ABA) created standards for law school accreditation in 1921 and has developed standards of ethics in the legal field since 1908.[27]

However, there are downsides to an industry-wide approach. First, there is a benefit to different social media platforms having different content moderation policies. If all major social media companies moderated content in the same or similar ways, users who disagreed with certain moderation decisions would have fewer places to go to express themselves online.

Second, these best practices would not be legally binding, meaning social media companies could choose not to follow them. Even if all the major social media platforms adhered to industry best practices, there would likely be smaller services that did not, and creators of harmful and illegal content would gather there. This already occurs on an Internet where most major social media platforms have similar, though not identical, content moderation policies, leading bad actors to congregate on less-policed platforms. 4chan, an anonymous forum-based social media platform notable for its lack of rules, has become synonymous with harmful or controversial user behavior, including celebrity nude photo leaks, the Gamergate movement, cyberbullying, and fake bomb threats.[28] When 4chan cracked down on some of these activities, a similar platform with even fewer restrictions on user behavior, 8chan, grew in popularity, attracting conspiracy theorists and extremists.[29]

Finally, given the intense public and media scrutiny directed at major social media companies—part of the larger “techlash” against big tech companies—many critics would be skeptical of an industry-led approach.[30] Social media companies would still take the blame for content moderation failures or controversies. In order for both platforms and users to benefit from content moderation standards, there needs to be third-party involvement to lend legitimacy to the effort.

Rule Changes

Instead of relying solely on social media companies to solve the debate surrounding online political speech, the second category of proposals would involve legislative or regulatory changes that would impact how those companies could do business. These proposals include transparency requirements for social media platforms, an “equal time rule” for online political advertisements, reinterpreting the First Amendment to apply to social media companies, and regulations on social media algorithms and targeted advertising.

Government intervention could lend legitimacy to efforts to change the way social media handles political speech, but it could also create further polarization. For example, when the Biden administration established a Disinformation Governance Board at the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) in April 2022, critics quickly characterized it as an Orwellian “Ministry of Truth,” until DHS eventually shut down the board in response to the backlash.[31] Without bipartisan consensus, legislative or regulatory changes could seesaw back and forth with changes in political power, as has occurred with other partisan issues such as net neutrality.

Moreover, government intervention risks disrupting innovation in an ecosystem that has thrived for more than two decades in part due to the U.S. government’s light-touch approach to regulation. For example, some proposals could tie the hands of social media companies, preventing them from addressing controversial content that degrades the experience of their platforms or limits their ability to deliver targeted advertising to users and keep their services free to use.

Transparency Requirements

One proposed rule change would require social media platforms to be more transparent in their content moderation. A transparency requirement would continue to allow companies to set their own rules for what content is not allowed on their platforms but would require them to be clear about those rules and how they enforce them. Platforms would also be responsible for enforcing their rules consistently. Some advocates also want social media companies to increase transparency of their algorithms used to recommend content.

More transparent content moderation would help address concerns that platforms are biased against certain demographics or ideas. Platforms would have to clearly lay out what content and behavior are not allowed, how the platforms find and respond to banned content, how users can report banned content, and how users can appeal moderation decisions. Platforms would then have to adhere to those standards consistently and report regularly on their content moderation, with publicly accessible data on how many posts were removed and users were banned in a given time period, why those actions were taken (i.e., what rules were violated), how many of those decisions were appealed, and how many of those appeals were successful.

This transparency would also have benefits for data collection and research. Social media researchers could more easily track trends in content moderation and the prevalence of different forms of harmful and illegal content. This would lead to increased platform accountability and potentially help platforms, governments, and other organizations formulate a response to forms of harmful and illegal content.

Algorithmic transparency, on the other hand, would require platforms to give information about how their various algorithms work. This could include information on how algorithms sort and recommend content, target advertisements, and moderate content. Proponents argue this would reveal whether platforms are amplifying harmful content. But algorithmic transparency requirements could reveal proprietary information competitors could use. The effectiveness of a social media company’s algorithms is part of what draws users to a platform, keeps users on the platform, and earns companies advertising revenue. Any algorithm transparency requirements should not compel companies to disclose proprietary information about their algorithms to the public.

One recent effort to mandate increased transparency from social media companies, the Platform Accountability and Consumer Transparency (PACT) Act, S. 797, would require increased transparency surrounding platforms’ content moderation policies and practices.[32] However, the bill’s requirement that platforms remove illegal content within four days could lead to platforms over-censoring content by removing content that is not actually illegal, which would negatively impact free speech online. In addition, the bill would also give the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) the power to take action against platforms for failing to remove policy-violating content, which would incentivize platforms to create lax policies that would allow more harmful-but-legal content most users do not want to see.[33]

Florida’s Transparency in Technology Act is another attempt to mandate increased transparency. But it also includes requirements that could create more problems than they solve. Related to transparency, it would require platforms to stop frequently changing their terms of service and obtain consent from users before changing their terms of service.[34] This would impede platforms’ ability to respond to new challenges and adapt to evolving situations.

Some transparency requirements are necessary to increase social media platform accountability, increase user trust, and improve social media research. But transparency requirements alone will still not solve the debate surrounding what forms of content should remain online.

Equal Time Rule

A second proposed rule change would specifically tackle the issue of political advertising on social media. This proposed “equal time” rule would require social media companies to give political candidates equal access to political and targeted advertising on their platforms regardless of party. Candidates would have the option to target the same audience their opponents target in order to combat opposing messages or correct false claims.[35]

The existing equal time rule, which applies to radio and television, arose from the Radio Act of 1927 and the Communications Act of 1934 and requires broadcasters to provide political candidates with equal treatment. If a broadcaster sells airtime to one political candidate, they must provide the same opportunity to that candidate’s opposition for the same price.[36]

Social media has become an increasingly important avenue for politicians to get their message to their intended audience. Between January 2019 and October 2020, Donald Trump’s campaign spent $107 million on Facebook ads, while Joe Biden’s campaign spent $94.2 million.[37] Proponents of an equal time rule argue that, given the gap in regulation between political ads on television and social media, candidates could take to social media to spread disinformation about their opponents, and target that disinformation to a specific audience. If opponents could target that same audience, they could correct that disinformation.

Additionally, proponents argue that, in the absence of an equal time rule, social media companies could sell ads to certain candidates and deny them to others, potentially influencing election outcomes. However, despite claims to the contrary, there is no evidence of major social media companies displaying political bias in their content moderation.[38] Additionally, not all false or misleading political ads come directly from politicians or their campaigns; they can instead come from unaffiliated individuals or organizations that support or oppose a certain candidate, party, or policy, as well as from bad actors such as the allegedly state-sponsored Russian “troll farms” that interfered in the 2016 U.S. presidential election.[39]

A more effective approach to false or deceptive political ads on social media would be legislation that would require social media companies to increase transparency of paid political advertising on their platforms and make reasonable efforts to ensure foreign entities do not purchase political ads. This type of requirement would create parity between the transparency requirements for online and offline political ads and reduce the risk of foreign interference in U.S. elections.

Even if Congress did create transparency requirements for online political advertising, doing so would not address the larger controversy surrounding political speech on social media. There is plenty of political content on social media that is not advertising, including misinformation, disinformation, and hate speech. These forms of content are difficult to regulate without infringing on users’ or companies’ First Amendment rights, and will require a different approach.

First Amendment Reinterpretation

The most significant proposed rule change to address political speech on social media involves reinterpreting the First Amendment. Currently, the First Amendment only protects Americans from government censorship: Government actors cannot place limits on legal forms of speech or punish people for their speech. However, private actors, including companies, can restrict speech. For example, an employer can fire an employee for saying rude things to customers, a theater can kick out audience members who disrupt the movie, and a social media company can set rules for what content is allowed on its platform.

Reinterpreting the First Amendment would apply the same limitations to social media platforms that currently apply to government actors. Platforms could only restrict illegal forms of content, such as defamation, copyright infringement, and child sexual abuse material.

Proponents of this change argue that the largest social media companies currently have too much power to restrict speech. They liken social media platforms to public forums such as public parks and streets, where speech is protected. If an individual is deplatformed from major social media platforms, they lose access to one of the primary forums where modern political discourse takes place.[40]

Applying the First Amendment to social media companies would require courts to reverse decades of precedent stating that the First Amendment only applies to government actors, denying that social media platforms are public forums, and protecting companies’ own First Amendment rights to exercise editorial control over the content on their platforms.[41] This would also have ramifications for other private actors’ speech restrictions. Courts would have to redraw the lines of when it is acceptable for private actors to restrict speech and when it is not.

Finally, holding social media companies to a First Amendment standard for their users’ speech would completely change the landscape of the Internet. Currently, social media platforms remove millions of posts containing prohibited content many users do not want to see. Between April and June 2020, Facebook removed 22.5 million posts that violated its hate speech rules, 35.7 million posts that violated its rules regarding adult nudity and sexual activity, and 7 million posts that contained COVID-related misinformation.[42]

The First Amendment standard for government censorship of free speech is strict because, left unchecked, governments have enormous power to control speech and punish people for speech deemed unacceptable. Authoritarian regimes throughout history and around the world have imprisoned and killed journalists for reporting on government misconduct and regular people for protesting against the government or expressing ideas the government disagrees with. Companies, no matter how large or well funded, do not have the power to imprison people or put them to death for their speech.

There are a number of clear and compelling reasons why the law treats censorship from government actors and private actors differently. Without some amount of discretion to remove harmful-but-legal speech, social media platforms would become cesspools of spam, violence, and hateful language, making the Internet a worse place overall. Efforts to solve the issue of political speech online must specifically address the forms of content reasonable people from both sides of the aisle agree is harmful and create a consensus on how platforms should respond to this content that does not rely on the strict standards in the First Amendment.

Regulations on Algorithms and Targeted Advertising

The final proposed rule change to address political speech on social media would impose regulations on social media algorithms and targeted advertising. Algorithms and targeted advertising are key components of social media companies’ business models. An innovative algorithm that recommends relevant content to users can help social media companies build and maintain a strong user base, and targeted advertising is most companies’ primary source of revenue.

Proposed regulations would bring about major changes to the social media ecosystem by restricting platforms’ ability to use algorithms to recommend content or target advertisements to users. Some of these proposals would tie these restrictions to an existing law, Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, which protects online services and users from liability for third-party content.[43]

H.R. 8922, the Break Up Big Tech Act of 2020, would eliminate Section 230 protections for online services that sell targeted advertisements or display content in any order other than chronological.[44] H.R. 492, the Biased Algorithm Deterrence Act of 2019, and H.R. 8515, the Don’t Push My Buttons Act, would both eliminate protections for online services that filter, sort, or curate user-generated content.[45] Finally, S. 4337, the Behavioral Advertising Decisions Are Downgrading Services (BAD ADS) Act, would eliminate Section 230 protections for any online service that engages in behavioral advertising.[46]

Proponents of placing limits on social media algorithms and targeted advertising in order to restrict harmful political speech argue that platforms intentionally hook users on radical or extremist content because it keeps users engaged on their sites.[47] Without those algorithms, platforms couldn’t serve content to users based on their political beliefs, which proponents argue would lead to users engaging with less misinformation, disinformation, and extremism. Meanwhile, without targeted advertising, social media companies would have less incentive to keep people on their platforms.

However, restricting or disincentivizing the use of algorithms would negatively impact many of the features social media platforms offer, such as news feeds that sort stories according to what is most likely to interest users, and features that allow users to explore or discover new content that is similar to content they have liked or interacted with in the past. These features add immense value to users, whereas simply displaying content in chronological order would force users to scroll through content that does not interest them.

Additionally, proposals targeting behavioral advertising fail to acknowledge the benefits of displaying ads according to users’ preferences. Not only is selling targeted ads an important source of revenue for many online services—enabling them to offer their services to users for free and to continue offering new features and innovations to the site—it also results in users seeing ads for products and services that are more likely to interest them.

Regulations on social media algorithms and targeted advertising would force platforms to reinvent their services, charging for services that they currently offer to users for free and eliminating many of the features users find most useful or engaging. Any approach to solving the issue of online political speech needs to fix what is wrong with social media without breaking the parts of social media that give users value.

Technical Reforms

The third category of proposed solutions would also require government involvement, but instead of changing the rules by which social media companies operate, the government would incentivize or require companies to make technical reforms to their algorithms or services. These proposals include either data portability and interoperability requirements or public funding for social media algorithms.

Data Portability and Interoperability Requirements

The first proposed technical reform would require large social media platforms to adhere to data portability and interoperability requirements. Data portability would allow users to export their data and transfer it between competing social media platforms. Meanwhile, interoperability would allow users of competing social media platforms to communicate with each other across those platforms, much like users of different email services can communicate with each other.[48]

The political speech argument behind data portability and interoperability requirements is similar to the argument behind many other proposed changes: that a few big companies host, and therefore control, the majority of online speech. This, proponents argue, gives those companies too much power over political discourse. It also means that, when users are banned from one of the major platforms or choose not to use it because they disagree with the platform’s content moderation policies, they lose access to the millions or billions of other users on that platform.

Data portability and interoperability would make it easier for users to switch between platforms when one platform bans them or enacts policies users disagree with. For example, users who take issue with Twitter’s misinformation policies could transfer their data to Parler but continue to communicate with their friends and colleagues on Twitter.

H.R. 3849, the Augmenting Compatibility and Competition by Enabling Service Switching (ACCESS) Act of 2021, would require large social media platforms, online marketplaces, and search engines to allow users to export and transfer their data and maintain interoperability with competing businesses. The FTC could take action against platforms that fail to meet these requirements for engaging in unfair competition.[49]

The downside of data portability and interoperability requirements is they would limit social media platforms’ ability to effectively moderate content by banning users who repeatedly violate their terms of service. A platform cannot effectively ban someone if that user can simply go to another platform and send messages to other users on the original platform. Though this would protect users who feel they were deplatformed for illegitimate reasons, it would also protect users who were deplatformed for legitimate reasons, such as threatening or harassing other users, selling counterfeit goods, spreading spam or malware, or posting illegal content.[50]

Social media platforms need effective mechanisms for keeping certain users off their platforms. Otherwise, these platforms would become overrun by bot accounts and spam, rendering them virtually unusable. Proposals to address political speech on social media need to protect users from being deplatformed for their political beliefs while also preserving platforms’ ability to deplatform users who engage in harmful or illegal behavior.

Public Funding

An alternative technical reform to address political speech on social media would involve the government providing funding for companies to improve their algorithms. This proposal is another response to claims that social media platforms’ algorithms, either intentionally to keep users hooked on a platform or unintentionally as a byproduct of how the algorithms work, promote objectionable content such as misinformation, extremist content, and conspiracy theories.

Social media algorithms are designed to maximize user engagement by prioritizing content that each user is likely to find entertaining, interesting, or useful. Algorithms use many different factors to rank content, including the content a user has engaged with in the past, searches the user has made, content similar users have engaged with, the amount of time the user spends viewing different forms of content, and who the user follows or frequently engages with on the platform.[51]

If an algorithm judges that a user has or is likely to have an interest in controversial political content, it may rank such content high on that user’s feed. This could lead to the user stumbling upon misinformation, conspiracy theories, or other content that could potentially lead the user down a rabbit hole of extremist content and even radicalization.

Although some critics accuse social media companies of purposefully designing their algorithms to radicalize users, the more likely explanation is that radicalization is a flaw in the way algorithms work to promote engaging content. To fix this flaw, the government could provide funding for social media companies to study how their algorithms end up promoting extremist content and either improve their algorithms or create better algorithms that do not promote this content.

However, many social media critics would oppose public funding going to social media companies, particularly the largest social media companies that have come under the most scrutiny for their handling of political speech. There is a perception that these companies have enough resources to fix all the flaws with their algorithms and choose not to do so in order to continue profiting off of radical content. Public funding going to these companies that critics believe are already too large and too profitable in order to fix problems the companies could afford to fix on their own would be highly controversial.

In addition, a lack of funding is not the main problem social media companies face when it comes to political content. A larger problem is the lack of consensus on how social media should handle political speech. Social media companies cannot create algorithms that do not promote extremist content, misinformation, or conspiracy theories if there is no consensus on what qualifies as extremist content, misinformation, and conspiracy theories. These are highly politicized terms, and until there is a consensus, social media companies risk just as much or more backlash for changing their algorithms.

Structural Changes

The fourth category of proposals would involve extensive government intervention to change the way social media operates on a structural level. This includes breaking up large social media companies, regulating them as “common carriers,” nationalizing them, or creating a government-run social media platform. For the most part, these proposals are an overreaction to the problems that exist in social media, are unlikely to effectively solve those problems, and could introduce new problems for consumers and businesses.

Antitrust

The first structural change to address political speech on social media would involve breaking up the social media companies that host the majority of online speech. The argument for this approach is similar to many other proposals: that a select few companies have too much control over online speech and political discourse. These companies make decisions about what content is or is not permitted on their platforms as well as how content is promoted.

Critics argue that social media companies’ power over the speech on their platforms is a threat to democracy. They claim that social media has exacerbated political polarization by creating echo chambers, powered both by algorithms that only show users content similar to what they have engaged with in the past and by the ease with which users can seek out people who agree with them and opinions that affirm their own. They also blame social media for the spread of misinformation and online attacks against marginalized groups. Finally, critics point out that social media is vulnerable to abuse by highly coordinated actors seeking to spread disinformation and influence election outcomes.[52]

Some critics even accuse social media companies themselves of interfering with election outcomes. During the 2020 U.S. presidential election, Twitter and Facebook restricted the spread of a New York Post article alleging that Hunter Biden, son of then-candidate Joe Biden, had connections to China and Ukraine. Some Republican lawmakers accused the platforms of interfering with the election and used the platforms’ actions as proof of their alleged bias against conservatives.[53]

Proponents of breaking up large social media companies would rather see several smaller social media companies that all compete with each other and have different user bases and content moderation practices. Each of these smaller companies would have power over a smaller portion of online speech, and it would be easier for users who disagree with one platform’s policies to move to a different platform.

However, breaking up the companies that currently dominate social media is no guarantee that other companies won’t take their place and become equally or more dominant. Network effects are particularly strong in social media: The value of a social media platform increases with its user base.[54] Users want to be on the same platform as their family, friends, and colleagues are.

Additionally, large firms are not inherently problematic or anticompetitive. In fact, there is a great deal of competition in social media, with smaller companies such as Reddit, Pinterest, Snapchat, and Tumblr able to coexist alongside Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube, and newer competitors such as TikTok able to capture a large, thriving user base over a relatively short span of time with new features that appeal to users. The goal of antitrust should be to promote consumer welfare and innovation, not simply to break up any firm that meets an arbitrary size-based threshold.[55]

When it comes to content moderation, large companies have many advantages over smaller ones. These larger companies have more resources to devote to content moderation, including hiring human moderators who can make more accurate and nuanced decisions than algorithms can. They can also continue to innovate and experiment with new ways to moderate content, such as Twitter’s Birdwatch program.

Finally, there is no guarantee that smaller companies would be any less vulnerable to manipulation or that having more small social media platforms would lead to less political polarization. In fact, the opposite may be true. Because of their larger user bases, platforms such as Facebook and Twitter have plenty of users across the political spectrum. But smaller platforms that cater to specific groups or ideologies could create insulated online communities, such as Parler’s largely conservative user base. This would strengthen polarization, not weaken it.

The economic arguments behind breaking up large social media companies are deeply flawed and based in an approach to antitrust that deprioritizes innovation and consumer welfare. Dividing up users among a larger variety of smaller platforms would only make it more difficult to come to a consensus on how to address political speech on social media.

Common Carrier Regulation

A second structural change would impose common carrier regulations on major social media companies. This would require social media platforms to “carry” all legal speech. They could no longer remove harmful-but-legal content or deplatform individuals who break the platform’s terms of service.

The term “common carrier” emerged in the context of transportation and was later applied to telecommunications.[56] When a transportation service such as a railroad or public bus, or a telecommunications service such as a telephone or broadband provider, makes its service available to the general public for a fee, as opposed to offering the services on a contract basis with specific customers under specific circumstances, it is classified as a common carrier.[57] Telecommunications common carriers are subject to regulations laid out in the Communications Act of 1934 (and amended in 1996), including nondiscrimination requirements that make it unlawful for these companies to deny their services to certain customers.[58]

Proponents of regulating major social media companies as common carriers argue that these companies currently have too much power and control over political discourse, which threatens free speech.[59] They can freely remove posts and ban users, including world leaders, for violating their terms of service.[60] With so much of modern discourse occurring online, particularly on a few key platforms, the decision of one or a few companies can have an outsized impact on the overall political landscape, even influencing election outcomes.

By this reasoning, proponents argue that it is in the public and national interests to regulate social media companies as common carriers. Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas has argued that such a law would not violate the First Amendment.[61] One such proposal currently facing Congress is S. 1384, the 21st Century Foundation for the Right to Express and Engage in (FREE) Speech Act, which would regulate social media platforms with more than 100 million users as common carriers.[62] Texas and Florida have both passed laws to treat social media platforms like common carriers, although these laws have faced legal challenges.[63]

Even if imposing common carrier regulation on major social media companies would pass First Amendment scrutiny, doing so would ruin social media for the majority of its users. Many of the major social media platforms’ terms of service bar content that is not illegal under U.S. law but that the platforms have determined is detrimental to their users. As common carriers, platforms would no longer be permitted to remove this content or ban users for posting it, which would lead to a flood of harmful and controversial content, including hate speech, violence, sexual content, and spam. Rather than improving social media for users, common carrier regulations would only make social media a worse environment overall.

Nationalization

Arguably the most extreme structural change the government could enact would be to nationalize the largest social media companies. This would involve the federal government taking ownership or control over companies that are currently owned by shareholders.

Nationalization frequently occurs in developing countries as a means of taking control of foreign-owned assets and businesses in critical industries such as oil, mining, and infrastructure.[64] However, developed countries such as the United States have a history of nationalizing companies as well, albeit usually temporarily. For instance, the U.S. government nationalized certain companies that were critical to the war effort during World War I and II, including railroads, telegraph lines, coal mines, and firearms manufacturers. It has also nationalized banks and other companies during times of financial crisis; during the Great Recession, the U.S. government temporarily nationalized General Motors.[65]

Two exceptions to the United States’ temporary nationalizations are Amtrak and the airline security industry. The U.S. government created Amtrak in the Congressional Rail Passenger Service Act of 1970, consolidating 20 privately-owned passenger railroads that were struggling as automobiles overtook trains as Americans’ preferred mode of transportation.[66] The U.S. government later created the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) on November 19, 2001, in the Aviation and Transportation Security Act as a response to the September 11 terrorist attacks.[67]

Proponents of nationalizing major social media companies echo many of the same arguments as those of proponents of imposing common carrier regulations on these companies. They argue that so much of modern discourse takes place on these companies’ platforms, and the platforms have become so integral to the average American’s daily life, that they should be classified as a public good.[68] They argue that these companies are monopolies that currently have too much power over Americans’ speech, including the power to censor or deplatform individuals for their political beliefs.[69]

If the government controlled social media, it would be bound by the First Amendment and could not restrict legal forms of speech. And even if the takeover were temporary, proponents argue that the government could restore public trust in social media before once again privatizing those social media companies.[70]

History demonstrates that the U.S. government only nationalizes companies under extreme circumstances (usually involving national security concerns) and these nationalizations are almost always temporary. Even proponents of nationalizing the largest social media companies acknowledge that this outcome is unlikely.[71]

Social media does not pose a significant national security risk, and the multitude of platforms and ascent of new popular platforms such as TikTok suggest that the largest social media companies are not natural monopolies. The government is also unlikely to restore public trust in social media companies, given that the American public’s trust in its government has been on the decline for most of the Internet era.[72]

Social media also relies heavily on innovation and efficiency—two areas where governments tend to lack. In the context of political speech, these companies are constantly improving their moderation algorithms to detect and remove harmful content. And because the government is constrained by the First Amendment, while social media companies are not, nationalizing social media would also result in harmful-but-legal content overwhelming the Internet. Once again, this would make social media worse, not better.

Government-Run Social Media Platform

Instead of nationalizing the largest social media companies, the government could instead create its own social media platform, similar to public broadcasting stations such as National Public Radio (NPR) and the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS). Rather than replacing existing platforms, this public-funded platform would compete with Facebook, Twitter, and others and provide users with an alternative to those platforms.

The argument for a government-run social media platform is similar to the argument for nationalizing social media. The government is bound by the First Amendment and cannot censor legal forms of speech or punish individuals for their protected speech, unlike private companies, which are free to set their own rules regarding acceptable content on their platforms.

Creating a separate, government-run social media platform would have fewer downsides than would nationalizing the largest social media companies, but its success would depend on both the government’s ability to create and operate—and the public’s willingness to use—a new, public-funded social media platform.

In the case of NPR, the organization has been successful despite a decrease in radio listenership by taking advantage of new mediums, including podcasts, live streams, and smart speakers. When radio listenership declined 22 percent during the COVID-19 pandemic as fewer people were commuting to work, the total number of people consuming NPR’s content in some form actually increased by 10 percent.[73] This demonstrates that public-funded organizations are capable of modernizing and innovating in order to capture an audience.

However, radio and social media pose very different challenges for new entrants to the market, in part due to network effects. Although these effects don’t prevent new entrants from succeeding, they do make such success more difficult to achieve. New social media platforms thrive by taking a different approach and offering new features users enjoy—for example, TikTok’s ease of use, highly customized feed, and focus on short-form video content have helped the app attract its user base.[74]

The free speech angle of a government-run social media platform could be enough to attract users, as has been the case with Parler, which grew exponentially during the 2020 U.S. presidential election, gaining over 7,000 users per minute that November.[75] However, this approach also comes with significant downsides. Plenty of harmful or controversial content is protected speech, meaning a government-run social media platform will be overrun with this content compared with other platforms. Many people would not want to use such a platform, and the platform would likely attract bad actors who want to post and spread harmful content. Additionally, people with low trust in the government may not want to give a government-run social media platform their personal information.

Because of these disadvantages, a government-run platform would find it difficult to compete with established platforms. It also would not affect the way social media companies moderate content; the debate around political speech on existing platforms would remain unsolved.

Commissions, Boards, and Councils

The final set of proposals focus on building a consensus on what the problems are with the current state of online political speech and creating best practices for dealing with those problems that balance concerns over freedom of speech and harmful content. This would take place at either the company, national, or international level, each of which would come with its own benefits and limitations.

Building a consensus on what the problem is and how to solve it is a necessary step to addressing political speech on social media. Proposed solutions that only address claims that social media companies remove too much content or don’t remove enough content would only satisfy one side or the other. It may be impossible to satisfy all social media’s critics, but a commission representing various interests would come closest to achieving a workable compromise.

Company Oversight Boards

Company oversight boards would make decisions about individual social media companies’ content moderation policies and decisions. The goal of these boards would be to create external checks and balances on large social media companies that otherwise have a significant amount of control over users’ speech. In order for these boards to have some legitimacy, they would need to operate independently from the companies they are associated with and their decisions would need to be binding.

A blueprint for other social media oversight boards, Facebook’s Oversight Board It was conceptualized in 2018 and began operations in 2020.[76] It consists of between 11 and 40 members serving a maximum of three three-year terms. Users who have exhausted their appeals of one of Facebook’s content moderation decisions can appeal that decision to the board, and Facebook can also submit its own decisions for review. The board has the power to request information from Facebook, interpret Facebook’s Community Standards, and instruct Facebook to allow or remove content or uphold or reverse an enforcement action.[77]

The Oversight Board’s May 5, 2021, decision regarding Facebook banning former president Trump from its platform gained media attention and scrutiny.[78] The board upheld Facebook’s ban but criticized Facebook for indefinitely suspending Trump rather than taking one of its typical enforcement actions of removing offending content or suspending an account for a specified length of time, rather than permanently banning Trump’s account.[79]

Critics of Facebook’s Oversight Board have called into question the board’s efficacy given the limited number and types of cases it can hear.[80] Despite efforts to ensure the Oversight Board’s independence, it is still associated with Facebook, one of the primary targets of the recent techlash. Other companies seeking to emulate Facebook’s approach would likely encounter similar criticism and public doubt about its credibility.

Additionally, not every company has the resources Facebook does, making the establishment of an independent and well-funded external company board unfeasible. Facebook’s Oversight Board is a step in the right direction toward increased transparency and accountability, but it is not a model most companies will be able to implement and is unlikely to solve the debate over political speech on social media.

Company Advisory Councils

Company advisory councils provide nonbinding feedback and expertise about individual social media companies’ content moderation policies and decisions. For example, the short-video-sharing social media company TikTok has set up a number of advisory councils for different regions, such as the United States, Europe, and Brazil.[81] Similarly, the photo messaging social media company Snap operates an advisory board to solicit feedback from experts across its global community.[82] Advisory councils provide an opportunity for companies to seek regular outside input about their content moderation decisions and help bring in different stakeholders’ perspectives.

However, companies are not bound by any of the recommendations given by their advisory councils, and the value and impact of any feedback depends on the composition of the council and the willingness of a company to engage with that feedback. Moreover, companies typically choose the members of their advisory councils, so stakeholders that do not have a seat at the table may not have their interests sufficiently represented. As a result, advisory councils may help individual companies better solicit feedback from outside stakeholders, but they will likely not do enough to impact the perceived public legitimacy of controversial content moderation decisions or set broader industry norms and practices.

National Commission

Whereas company oversight boards such as Facebook’s Oversight Board only oversee the content moderation policies and decisions of one company, a national commission would make recommendations for all social media companies that operate in the United States.

Congress would create this commission and the speaker and ranking member of the House of Representatives would select the commission’s members to ensure bipartisan representation. Membership could include experts and thought leaders from civil society, academia, social media, and news media. Once formed, the commission would create a set of best practices for social media companies to follow regarding controversial political speech.

These best practices should remain broad and flexible enough to apply to a multitude of scenarios and adapt to new circumstances. For example, guidelines on misinformation should focus on best practices for identifying and removing misinformation rather than outlining specifically which beliefs or opinions qualify as misinformation.

Because government would be involved in creating and funding this commission, the commission could not legally require companies to follow its guidelines, as this would be a violation of the First Amendment. Government cannot instruct companies on what speech is or is not appropriate or punish companies or individuals for their speech. But companies that do follow the commission’s guidelines could point to this as an example of their good moderation practices.

There is evidence that some companies would find this guidance useful. In February 2020, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg expressed that he would welcome government guidance or regulation regarding harmful content on social media, stating that it would “[create] trust and better governance of the Internet and will benefit everyone, including [Facebook] over the long term.”[83] Companies such as Facebook that have been at the center of the techlash would not only have a way to prove that they are following best practices for content moderation, but there would also be someone else to “blame” for content moderation failures.

The primary benefit of a national commission is it requires reaching a consensus or compromise on important issues related to online political speech. Although this would be a difficult process given current ideological divides, it is a necessary first step. Additionally, while proponents of government regulation may be skeptical of voluntary guidelines, this approach sidesteps many of the First Amendment concerns that come with regulation.

However, although a national commission would be a step in the right direction toward consensus-building and the creation of best practices for content moderation, the debate over online speech is international. Companies that adhere to a national commission’s guidelines would still likely face criticism overseas from other governments that would not be involved in the process of setting the guidelines and may have different ideas about what good moderation practices look like.

Multistakeholder Forum