Cross-Border Data Flows: Where Are the Barriers, and What Do They Cost?

A growing number of countries are making it more expensive and time consuming, if not illegal, to transfer data overseas. This reduces economic growth and undercuts social value.

Data is the lifeblood of the modern global economy. Digital trade and cross-border data flows are expected to continue to grow faster than the overall rate of global trade. Businesses use data to create value, and many can only maximize that value when data can flow freely across borders, yet a growing number of countries are enacting barriers that make it more expensive and time consuming, if not illegal, to transfer data overseas. Some nations base their decisions to erect such barriers on the mistaken rationale that it will mitigate privacy and cybersecurity concerns; others do so for purely mercantilist reasons. Yet, whatever the motivation, as this report demonstrates, the costs of these policies are significant, not just for the global economy, but for the nations that “shoot themselves in the foot” by using these policies.

(View hi-res infographic:JPEG | PDF)

The increased digitalization of organizations, driven by the rapid adoption of technologies such as cloud computing and data analytics, has increased the importance of data as an input to commerce, impacting not just information industries, but traditional industries as well. The use of data analytics in virtually all industries has streamlined business practices and increased efficiency, but also made the movement of data more important. Organizations increasingly rely on data for a number of purposes, including to monitor production systems, manage global workforces, monitor supply chains, and support products in the field in real time. Companies collect and analyze personal data to better understand customers’ preferences and willingness to pay, and adapt their products and services accordingly. It is a simple fact that international trade involving consumers cannot take place without collecting and sending personal data across borders—such as names, addresses, billing information, etc.

Despite the significant benefits to companies, consumers, and national economies that arise from the ability of organizations to easily share data across borders, dozens of countries—across every stage of development—have erected barriers to cross-border data flows, such as data-residency requirements that confine data within a country’s borders, a concept known as “data localization.” Data localization can be explicitly required by law or is the de facto result of a culmination of other restrictive policies that make it unfeasible to transfer data, such as requiring companies to store a copy of the data locally, requiring companies to process data locally, and mandating individual or government consent for data transfers. These policies represent a new barrier to global digital trade. Cutting off data flows or making such flows harder or more expensive puts foreign firms at a disadvantage. This is especially the case for small and solely Internet-based firms and platforms that do not have the resources to deal with burdensome restrictions in every country in which they may have customers. In essence, these tactics constitute “data protectionism” because they keep foreign competitors out of domestic markets.

This report first analyzes the privacy and security “justifications” nations offer for enacting barriers to data flows, concluding that, while such policies may be well intentioned, these rationales are generally not valid. (A forthcoming Information Technology and Innovation Foundation report will focus on a third motivation—to enable surveillance and government access for law enforcement—and will explain how governments need to develop a revised framework to help them determine jurisdiction over data while also facilitating cooperation among governments.) The report then examines the economic rationales countries provide to justify their data-localization policies, explaining the shortcomings in those arguments and noting that such policies impose large costs on countries’ own economies. The report then proceeds to review the emerging body of research that estimates the cost of barriers to data flows in terms of lost trade and investment opportunities, higher information technology (IT) costs, reduced competitiveness, and lower economic productivity and GDP growth. These studies show that data localization and other barriers to data flows impose significant costs: reducing U.S. GDP by 0.1-0.36 percent; causing prices for some cloud services in Brazil and the European Union to increase 10.5 to 54 percent; and reducing GDP by 0.7 to 1.7 percent in Brazil, China, the European Union, India, Indonesia, Korea, and Vietnam, which have all either proposed or enacted data localization policies.

Finally, the report offers recommendations for policymakers in both the United States and other countries.

The Trump administration should:

- Negotiate trade agreements that prohibit and eliminate digital barriers.

- Develop better measures of the digital economy and trade.

- Expand the focus on digital economy and trade issues.

- Initiate enforcement cases against countries, such as China, that have enacted digital-protectionism policies.

- Propose and negotiate a “data-services agreement” to address digital trade barriers.

- Propose and negotiate a “Geneva convention on the status of data” to establish international legal standards for government access to data, to improve mutual legal-assistance processes, and to decide on a framework to manage questions on data-related jurisdiction issues.

For policymakers in other countries:

- Recognize the critical role of data flows and prohibit data-localization policies.

- Promote international interoperability in privacy and data protection.

- Encourage international organizations, such as the World Trade Organization and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, to focus on digital trade barriers.

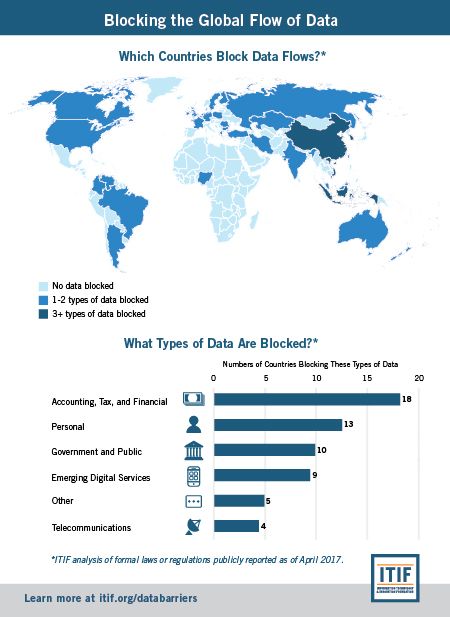

Data-Localization Policies Around the World

The table below captures most of the world’s data-localization policies. The entries with icons show where countries have enacted and implemented data localization policies targeting specific types of data. Other entries cover cases where countries have proposed, but not enacted, data localization policies or provide context for data-related policies, such as in the European Union. The list shows that data localization comes in many forms: While some countries enact blanket bans on data transfers, many are sector specific, covering personal, health, accounting, tax, gambling, financial, mapping, government, telecommunications, e-commerce, and online publishing data. Others target specific processes or services, such as online publishing, online gambling, financial transaction processing, and apps that provide services over the Internet (thereby bypassing traditional distribution).

In some cases (such as those for tax and accounting records), data localization stems from outdated legacy laws and rules formulated before the development of the Internet (e.g., laws that require documents to be held at the business’s premises). Other data localization stems from countries formulating laws to address technology issues (the Internet, data, or privacy). In a knee-jerk reaction, these countries, instead of tackling the actual issue (such as focusing on data protection or ensuring government access, instead of geography), require local data storage. For others, data localization is a mercantilist tool they think provides them with an advantage over foreign firms, often using public-policy concerns about privacy or cybersecurity as a smokescreen.

Results based on an ITIF analysis of formal measures (laws or regulations) that have been publicly reported as of April 2017. To suggest updates and additions, please contact [email protected].

Country | Type of Data | Data-Localization Policy |

Argentina |

| Argentina’s Data Protection Act prohibits the transfer of personal data to countries that do not have an adequate level of protection in place, but so far Argentina’s government has not determined which countries fall within this category. However, the Act states that the prohibition is not applicable when the data subject has given express consent to the data transfer. In addition, Argentina’s National Directorate for Personal Data Protection issued Provision no. 18/2015, which stated that cloud storage is considered an international transfer of data, so that software application that send data abroad must comply with the Data Protection Act. |

Australia | In 2012, Australia enacted the Personally Controlled Electronic Health Records Act, which requires that personal health records be stored only in Australia. | |

Belgium | Belgium’s laws require accounting and tax documents to be kept in the office, agency, branch, or other private premises of the taxpayer where they have been kept, prepared, or sent. Companies can apply to Belgian tax authorities for an exemption to this requirement. These accounting records may be kept in another place (such as overseas), provided that immediate access to the records can be granted or that such records can be provided on short notice. Furthermore, Belgium’s Companies Code requires companies to keep their register of shareholders and register of bonds at the registered office of the company. Since 2005, it has been possible to keep digital copies of these registries as long as they are accessible at the company’s registered office. | |

Brazil | In September 2013, Brazil began considering a policy that would have forced Internet-based companies, such as Google and Facebook, to store data relating to Brazilians in local data centers. It withdrew this provision from the final copy of the bill. Furthermore, in 2016, Brazilian government agencies, including the Secretary of Information Technology of the Ministry of Planning, Development, and Management, have included forced data localization as a requirement for public procurement contracts involving cloud-computing services. | |

Bulgaria | In 2012, Bulgaria enacted a new law—the Gambling Act—that required applicants for a gaming license to store all data related to operations in Bulgaria locally. Furthermore, the company’s communication equipment and central control point for IT must be in Bulgaria, another EU member country, or Switzerland. | |

Canada | Two Canadian provinces, British Columbia and Nova Scotia, have implemented laws mandating that personal data held by public bodies such as schools, hospitals, and public agencies must be stored and accessed only in Canada, unless certain conditions are fulfilled.The tender for the project to consolidate the federal government’s ICT services, including email, for 63 different agencies requires the contracting company to store the data in Canada (citing national security reasons). | |

China | China has one of the widest sets of data-localization policies, which stops the flow of data between China and the rest of the world. To start with, it has long limited data “imports.” For example, the Ministry of Public Security runs the Golden Shield program (commonly referred to as the “Great Firewall of China”), which restricts access to certain websites and services, particularly ones that are critical of the Chinese Communist Party. But, more importantly, from a trade perspective, China has made several policy changes in the wake of the Snowden revelations that restrict the cross-border transfer of data. For example:

| |

Colombia | In 2016, Colombia’s Ministry of Information and Communication Technology publicly called for data localization and released a document—on “Basic Digital Services”—that recommends that data-processing centers should be in Colombia, as they perceive storing data overseas to be too great a risk to network security and personal data. Furthermore, there are concerns that Colombia’s National Procurement Office (NPO) may include data localization requirements or other barriers to data flows as part of a cloud services procurement project for government agencies. Early drafts show the NPO is considering a vague and arbitrary “adequacy” assessment to decide which countries provide adequate data protection. The NPO has reportedly prepared a draft list of “adequate” countries, which does not include the United States, without detailing how these countries were assessed. | |

Cyprus |

| Cyprus has failed to replace several restrictive provisions under the Directive on Data Retention, which was declared invalid by the Court of Justice of the European Union (ECJ). This directive required data operators to retain certain categories of traffic and location data (excluding the content of those communications) for a period between six months and two years and to make them available, on request, to law-enforcement authorities for the purposes of investigating, detecting, and prosecuting serious crime and terrorism. |

Denmark | Since 2011, the Danish Data Protection authority has ruled in several cases against processing of local authorities' data in third countries (non-European Union) without using standard contractual clauses. Also, the Danish law on data retention is still in force after the ECJ ruled the Data Retention Directive invalid. In 2011, the Danish Data Protection Agency denied the city of Odense permission to transfer “data concerning health, serious social problems, and other purely private matters” to Google Apps, citing security concerns. Furthermore, Denmark’s Book Keeping Act requires companies to store accounting data in Denmark for five years. Under special circumstances, the Danish Commerce and Companies Agency may grant companies permission to preserve accounting records abroad. However, the practice has proven quite restrictive, and permission is seldom granted. | |

European Union | Data localization is a contentious issue in the European Union, as some members (such as France and Germany) push for localization in relevant policies, while others (such as the United Kingdom and Sweden) push for free flow of data across borders. The European Commission’s (EC) effort to build a Digital Single Market is a valiant attempt to remove barriers that inhibit digital economic activity, such as those that require data localization. Yet, as this report shows, many such barriers remain. Large U.S. firms ranked Europe as the area where data privacy and protection requirements represented the largest obstacle to doing business online. Andrus Ansip, EC vice president for the digital single market, has been pushing to remove localization barriers and wants to ban such measures, but his efforts are undermined by others (such as some in Germany and France) that do not want the EC to explicitly ban localization.A central part of the European Union’s policy platform that affects cross-border data transfers is its pursuit of global harmonization of privacy regimes. The EU’s law on personal data protection only allows for the transfer of such data to third countries outside the EU that it has determined provide an “adequate” level of protection. So far, the EU has only recognized 12 countries: Andorra, Argentina, Canada, Switzerland, the Faeroe Islands, Guernsey, Israel, the Isle of Man, Jersey, New Zealand, the United States (through the U.S.-EU Privacy Shield Framework), and Uruguay. EU personal data is technically not supposed to be transferred to any other country, although it is naïve to believe this is so. Europe has taken a hardline toward the United States about data transfers; however, when its own studies into data protection in other major countries, such as China, show that other countries have little or no level of data protection, it refrains from taking any action. This highlights how untenable the EU’s approach is as it tries to set up checkpoints for data flows to each and every country around the world. | |

Finland | Finland’s Account Act (1997) requires that a copy of companies’ accounting records be stored in Finland. Alternatively, the records can be stored in another EU country if a real-time connection to the data is guaranteed. | |

France | The French government has sought over the last few years to promote a local data-center infrastructure, which some have dubbed “le cloud souverain,” or the sovereign cloud. In 2016, a French government ministerial circular (dated April 5) on public procurement outlined that it is illegal to use a non-"sovereign" cloud (i.e., foreign cloud provider) for data produced by public (national and local) administration. All data from public administrations has to be considered as archives and therefore stored and processed in France. The French Blocking Statute (Law No. 80-538) makes it illegal to transfer information (such as data) overseas if the information is involved in legal proceedings, absent a French court order. | |

Germany | Germany, along with France, has been at the center of efforts to force companies to store data only in Europe or even in-country, such as through a “Bundescloud” (a cloud for government data) in Germany. This preference for digital protectionism stands in stark contrast to Germany’s otherwise open approach to global trade. Data requirements can vary by state in Germany. For example, the German state of Brandenburg requires that data on residents can only be stored on cloud computing services located in the state.On December 18, 2016, Germany introduced local data-storage requirements for a type of telecommunications metadata, through a law that will come into force on July 1, 2017. The law aims to generate and retain telecommunications metadata—the who, when, where, and how, not the what (the content)—of telecommunications for law enforcement and security purposes. This can include citizens’ call records, phone numbers, location information, Internet protocol addresses, time and data of Internet usage, and billing information. Germany’s Commercial Code requires companies to store accounting data and documents locally. Also, Germany’s tax code requires all persons and companies liable for German taxes to keep accounting records in Germany (with some exceptions for multinational companies). Furthermore, for data processed by public bodies, there does not seem to be a provision which expressly requires data to be held in Germany. However, such data processing outside the German territory has to be carefully checked. | |

Greece | In 2001, Greece introduced data-localization requirements through a law implementing the EU Data Retention Directive, which stated that “Data generated and stored on physical media, which are located within the Greek territory, shall be retained within the Greek territory.” Even though the Data Retention Directive was invalidated by the European Court of Justice, Greece has not yet reformed the law. The European Commission has also criticized the law as being inconsistent with the E.U. single market, but it remains in effect. | |

India | India has proposed a range, and enacted some, laws and regulations requiring data localization. India’s Ministry of Communications and Technology enacted data transfer requirements as part of a 2011 change to privacy rules that could be (but haven’t been) used to restrict data flows containing personal information. These rules limit the transfer of “sensitive personal data or information” abroad to only two restrictive cases—when “necessary” or when the subject consents to the transfer abroad. Because it is difficult to establish that a transfer data abroad is “necessary,” this provision would effectively ban transfers abroad except when an individual consents. The ministry clarified that these rules only apply to companies gathering data on Indians and only when the company is located in India. On paper these laws are restrictive, however, India has thus far not used the law to require local data storage.In 2012, India enacted a “National Data Sharing and Accessibility Policy,” which effectively means that government data (data that is owned by government agencies and/or collected using public funds) must be stored in local data centers.In February 2014, the Indian National Security Council proposed a policy that would institute data localization by requiring all email providers to set up local servers for their India operations and mandating that all data related to communication between two users in India should remain within the country.In 2014, India’s enacted the Companies (Accounts) Rules law that required backups of financial information, if primarily stored overseas, to be stored in India. In 2015, India released a National Telecom Machine-to-Machine roadmap that requires all relevant gateways and application servers that serve customers in India to be located in India. The Roadmap has not yet been implemented.Indian government agencies have also made data localization a requirement for cloud providers computing for public contracts. For example, in 2015, India’s Department of Electronics and Information Technology issued guidelines that cloud providers seeking accreditation for government contracts would have to require them to store all data in India. | |

Indonesia | Indonesia has a range of data-localization laws that cover a broad range of sectors and technologies. Indonesia has been expanding its range of localization policies as part of a persistent attachment to state-directed development and digital protectionism strategies.In 2012, Indonesia enacted a rule—regulation no. 82— regarding the Provision of Electronic System and Transactions, which requires “electronic systems operators for public service” to store data locally. Indonesian officials have stated that “public service” means any activity that provides a service by a public service provider, consistent with the broad definition of the term used in the implementing regulations to the 2009 Public Service Law. In 2014, Indonesia seemed to follow through on this as the government began considering a “Draft Regulation with Technical Guidelines for Data Centres” that would require Internet-based companies, such as Google and Facebook, to set up local data storage centers.The potentially broad effect of the law was evident by a spokesman’s comments that the law “covers any institution that provides information technology-based services.” Most recently, Indonesia’s Technology and Information Ministry issued regulation 20/2016 on personal data protection that stated that electronic system providers are required to process protected private data only in data centers and disaster recovery centers located in Indonesia.Localization policies are also spreading to other areas. In 2014, Indonesia’s central bank enacted a rule that requires e-money operators to store data locally. In 2016, Indonesia’s Ministry of Communications and Informatics issued Circular Letter No. 3, which notifies over-the-top service companies (such as Skype and WhatsApp) about new regulations, including the requirement to store data locally. | |

Iran | Iran does not have an explicit personal data-protection act, but it has been slowly moving toward developing its own national intranet—the Halal Internet—to separate itself (as best it can) from the rest of the Internet, including moves toward greater data localization. Iran’s government operates an extensive online censorship regime. During political protests in 2009, Iran blocked Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube. In 2015, Iran launched its own search engines, which only show approved websites. In August 2016, Iran set up its first government-paid cloud data center. In May 2016, Iran ordered foreign messaging apps, such as WhatsApp and Telegram, to store data from Iranian users locally. | |

Kazakhstan | Since 2005, Kazakhstan has required that all domestically registered domain names (i.e., those on the “.kz” top-level domain) operate on physical servers within the country). Furthermore, in 2015, Kazakhstan enacted an amendment to its personal data-protection law that requires owners and operators collecting and using personal data to keep such data in-country. The requirement for localization of personal data applies to companies established in Kazakhstan and individual proprietors in Kazakhstan, including branches and representative offices of foreign companies. It is not clear whether the localization requirement should apply to foreign companies without any legal presence in Kazakhstan but whose websites are accessible in Kazakhstan. | |

Kenya | In June 2016, Kenya released its draft National Information and Communications Technology Policy, which aims to update the government’s efforts to revise ICT-related economic policy. In the section on data centers, under the title of policy objectives, the report states that policy should “facilitate the development and enactment of legislation to support growth in IT service consumption—as an engine to spur data center growth.” While no data localization has been enacted (yet), this sounds suspiciously like an attempt to use localization for mercantilist ends. | |

Luxembourg | In 2012, Luxembourg’s financial services regulator issued a circular that financial institutions are required to process their data in-country, unless the overseas entity is part of the same company or if the data is transferred with explicit consent. | |

Malaysia | In 2010, Malaysia enacted the Personal Data Protection Act, which came into force in 2013. Personal data cannot be transferred outside Malaysia, unless the action has been approved by the Malaysian government. Exceptions to this rule include if the data subject has given approval, the transfer is part of a contract between the data subject and data user, if reasonable steps have been taken to protect the data, or if the transfer is necessary to protect the data subject’s vital interests. As with other countries, a consent requirement for transfer abroad is a burdensome requirement to satisfy. | |

The Netherlands | The Netherlands Public Records Act requires public records to be stored in archives in specific locations in the country. | |

Nigeria |

| In 2014, Nigeria enacted the “Guidelines for Nigerian Content Development in Information and Communications Technology (ICT),” which introduced several restrictions on cross-border data flows and mandated that all subscriber, government, and consumer data be stored locally. Furthermore, in 2011, Nigeria’s Central Bank introduced a measure that required all point-of-sale and ATM transactions to be processed locally. Under no circumstances are these transactions to be processed outside Nigeria. |

New Zealand | New Zealand’s Internal Revenue Act requires businesses to store business records in local data centers. | |

Poland | Poland required e-commerce entities to store customer details in Poland, but after an intervention by the European Commission, Poland was forced to lift the requirement, and it is now sufficient that the servers are in the EU. The Polish Gambling Act also requires online gambling firms to store all data relating to customer betting in the European Union. | |

Romania | In 2015, Romania enacted new online gambling regulations that requires all data on players and their gambling activities to be stored in Romania. | |

Russia | Russia operates one of the most extensive sets of data-localization policies in the world. In 2015, Russia enacted a Personal Data Law that mandates that data operators who collect personal data about Russian citizens must “record, systematize, accumulate, store, amend, update and retrieve” data using databases physically located in Russia. This personal data may be transferred out, but only after it is first stored in Russia. Russia has threatened to shut down and fine websites, such as LinkedIn, that refuse to store data locally.Furthermore, in 2016, Russia enacted extensive new data-localization requirements for telecommunications data. Russia’s approach is much broader than other countries’ telecommunications data-retention requirements, as it requires companies to store the actual content of users’ communications for six months, such as voice data, text messages, pictures, sounds, and video, not just the metadata (the who, when, and how long of communications). Second, it requires telecommunications companies and ISPs to cut services to users if they fail to respond to a request from law enforcement to confirm their identity (which raises a range of privacy issues). | |

South Korea | In South Korea, the Personal Information Protection Act requires companies to obtain consent from “data subjects” (i.e., the individuals associated with particular data sets) prior to exporting that data. The act also requires “data subjects” to be informed of who receives their data, the recipient’s purpose for having that information, the period that information will be retained, and the specific personal information to be provided. This is clearly a substantial burden on companies trying to send data across borders.Korea has used data localization requirements to protect local e-commerce and online payment operators. Korea’s Regulation on Supervision of Credit-Specialized Financial Business prohibited e-commerce firms from storing Korean customer’s credit card numbers outside the country. In 2013, Korea slightly revised this rule by allowing certain foreign e-commerce firms (those with stores in more than five countries) to store such data abroad.In 2014, South Korea enacted a law—Act on the Establishment, Management, Etc. of Spatial Data—that prohibits mapping data from being stored outside the country due to security concerns. Korea is the only significant market in the world that maintains data localization requirements for mapping data. Korea has defended the policy as it wants to limit the availability of high-resolution commercial satellite imagery of Korea for national security reasons, even though such imagery is already available commercially. In 2015, Korea enacted the Act on Promotion of Cloud Computing and Protection of Users. Subsequent guidelines—the Data Protection Standards for Cloud Computing Services Guidelines—contain rules that effectively require data localization as cloud computing networks serving public agencies have to be physically separate from networks serving the general public. While these guidelines are only “recommended” and there is no penalty for non-compliance, Korean institutions usually follow such guidelines. This discriminatory policy may have a significant affect as it applies to thousands of institutions, such as educational institutions, public banks, and public hospitals. | |

Sweden | Sweden’s Financial Services Authority requires “immediate” access to data in its market supervision, which, according to business, the supervisory body interprets as being given physical access to servers. This amounts to de facto localization, as companies are forced to store data in Sweden.Furthermore, Sweden has accounting requirements that force companies to store data about current company records and accounts in Sweden for seven years. In addition, there is the potential for Swedish government regulations to be interpreted such that data processed by a government agency needs to be held within Sweden, which would obviously affect cloud computing and ultimately result in data localization. | |

Taiwan | Article 21 of Taiwan’s Personal Data Protection Act permits government agencies the authority to restrict international transfers in the industries they regulate, under certain conditions, such as when the information involves major national interests, by treaty or agreement, inadequate protection, or when the foreign transfer is used to avoid Taiwanese laws. | |

Turkey | In 2013, Turkey enacted a law—the Law on Payments and Security Settlement Systems, Payment Services and Electronic Money Institutions—that forces Internet-based payment services, such as PayPal, to store all data in Turkey for ten years. PayPal withdrew from the country after refusing to abide by this data localization requirement.In 2016, Turkey enacted the Law on the Protection of Personal Data, which limits transfer of personal data out of Turkey and may require firms to store data on Turkish citizens in country. The law places burdensome obligations on data controllers and processors, requiring “express consent” from individuals to transfer personal data to another country. The need for specific and individual engagement holds the potential to act as de facto data localization. Turkey’s new law adopts a similarly untenable and unrealistic approach to international data flows and protection as that of the European Union by requiring country-by-country assessments of privacy protections. Turkey’s newly formed “Data Protection Board” (staffed with political appointees, not technical staff) will assess whether other countries provide an “adequate” level of privacy protection. Under this law, if the country receiving data from Turkey does not offer “adequate” protection, the Data Protection Board must provide permission for each transfer. | |

United Kingdom | According to the United Kingdom’s Companies Act 2006, "if accounting records are kept at a place outside the United Kingdom, accounts and returns ... must be sent to, and kept at, a place in the United Kingdom, and must at all times be open to such inspection." | |

United States | The United States has proposed or enacted a few data localization requirements, most of which focus on public procurement. Most recently, the United States pushed for financial services data to be exempt from rules in the Trans Pacific Partnership that prohibited countries from enacting barriers to data flows. However, after the agreement was finalized, the United States sought to limit the scope of this provision through bilateral discussions and via provisions in ongoing negotiations for a Trade in Services Agreement.In 2016, the U.S. Internal Revenue Service issued publication 1075—Tax Information Security Guidelines For Federal, State and Local Agencies—which outlined (section 9.3.15.7) that federal agencies must “restrict the location of information systems that receive, process, store, or transmit [federal tax information] to areas within the United States territories, embassies, or military installations.”In 2015, the U.S. Department of Defense issued revised rules that require all cloud-computing service providers that work for the department to store data domestically. Domestic data storage requirements are sometimes a requirement for other federal public procurement contracts, but are not an explicit government-wide policy.Similarly, some state and local governments impose these requirements in contracts. The City of Los Angeles, for example, required Google to store its data within the continental United States as a condition of its contract with the city. In 2004, Tennessee enacted a bill (SB 2344) that gives a preference to local providers when evaluating proposals for state-level procurement contracts requiring data entry and/or call center services. The preference is provided when the contract is provided by U.S. citizens and other persons authorized to work in the United States. Similarly, in 2004, an Ohio state representative proposed a bill (No. 459) that would prohibit transferring personal data overseas without written consent as part of any state procurement projects. The bill never became law. Similar laws were proposed in Missouri and other states. In 2011, a New York State senator proposed a law (S3713) that would prohibit the transfer of personal information outside the United States without the prior written consent of the consumer. It was intended to favor local companies, whilst tangentially trying to connect overseas data storage to consumer fraud and theft. | |

Vietnam | Vietnam has extensive data-localization policies in place as part of broad efforts to control Internet-based activities (for both political and commercial purposes). For example, Vietnam forbids direct access to the Internet through foreign ISPs and requires domestic ISPs to store information transmitted on the Internet for at least 15 days.In January 2016, Vietnam released a draft regulation—Draft Decree Amending Decree 72—for over-the-top services (such as WhatsApp and Skype) that included a forced data-localization requirement. In 2013, Vietnam enacted a law—Decree 72—on the management, provision, and use of Internet services and online information that requires a broad range of online companies (such as social networks, online game providers, and general information websites) to have at least one server in Vietnam “serving the inspection, storage, and provision of information at the request of competent state management agencies.” In 2008, Vietnam enacted a law—Decree 90—against spam (unwanted emails and text messages) that forces relevant advertising companies involved in these activities to send emails and texts only from servers in Vietnam. | |

Venezuela | Venezuela has passed regulations requiring that IT infrastructure for payment processing be located domestically. |