American Culture and the Decline of the Digital Spirit: Part II

To paraphrase Rodney Dangerfield, when it comes to explaining a nation’s techno-economic performance, culture gets no respect. It can’t be easily quantified, so economists tend to ignore it. It concerns the nation rather than the enterprise, so business scholars largely ignore it as well. And it’s removed from day-to-day politics, so political scientists often ignore it too. But despite this, culture plays a critical role in a nation’s techno-economic success.

I don’t mean culture in the narrow sense of just books, movies, and music. I mean the overarching narratives and shared views held by society, and especially by what Michael Lind calls the managerial overclass—"the university-credentialed elite that clusters in high-income hubs and dominates government, the economy, and the culture.” It’s the scribblings and pronouncements of these folks that shape the beliefs most Americans have on many issues, including digitalization and now AI.

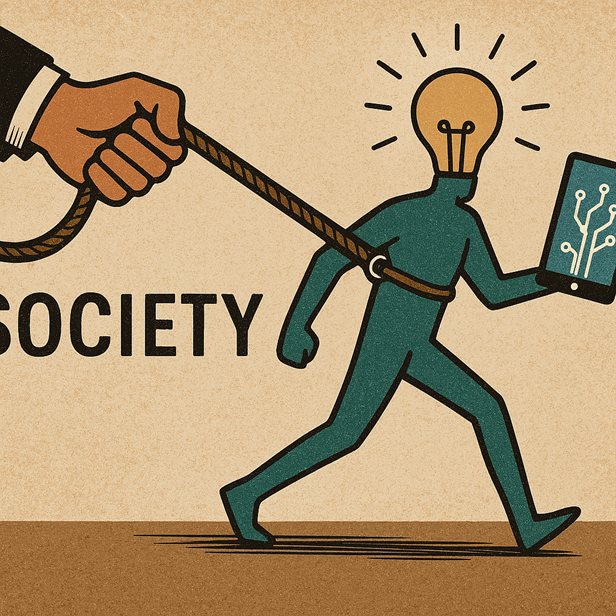

Unfortunately, this knowledge elite in America, as well as in Commonwealth nations and Europe, now forms a stiff collective headwind against digitalization—both against the competitive success of digital firms and against the overall process of digital transformation (i.e., the deep digitalization of most sectors of the economy and society, including through AI).

It’s hard to say when American culture turned from supportive to oppositional, but perhaps 2011, the year Steve Jobs died, is as good a demarcation point as any. Since then, the elite class narrative has transformed from one generally supportive of digital progress, or at worst neutral, to one of critique, disdain, and mockery.

Before 2011, if you wanted to be one of the “cool kids,” you waxed poetic about digital transformation, how it would spur growth and democratize information. Now, anyone seeking cocktail party acceptance or a TED Talk speaking slot must obligatorily offer one or more critiques of not just tech, but BIG TECH. If before you marveled at Moore’s Law, 3G, and Web 2.0, now you bemoan how tech is destroying democracy, eroding privacy, and killing jobs. And others nod their heads and murmur in affirmation.

The list of complaints seems endless, providing the cool kid skeptics with a panoply of causes and talking points. Indeed, elites now compete fiercely to produce the most aggressive takedown. Anti-establishment, anti-intellectual property “activist” Cory Doctorow coined the term “enshittification.” Very clever, Cory. But what about broken brains? That’s even better. Right wing commentator Matt Walsh says AI has declared “war on humanity.” Better still, we’re entering a “digital dark age.” Why not just be done with it and declare “digital: the spawn of Satan”? Kind of hard to top that one.

Let’s look at AI. Of course, according to its critics, AI is:

- Biased

- Killing jobs

- Violating privacy

- Creating security risks

- Destroying the environment

- Enabling price discrimination

- Facilitating anti-competitive collusion

- Jacking up electric rates

- Concentrating power into the hands of a few tech bros

- Flooding the internet with garbage

- Exploiting labor

- Enabling racially biased predictive policing

- Supporting digital redlining

- Creating data deserts

- Undermining learning

- Powering misinformation and disinformation

- Leading to polarization and echo chambers

- Enabling widespread manipulation

- Atrophying human capabilities

- Exacerbating economic inequality

- Deskilling professions

- Enabling theft of artists’ content

- Leading to social isolation

- Eroding trust

- Enabling avoidance of accountability

- Destroying small businesses

- Misdiagnosing medical issues

- Not accessible for the disabled

- Widening the digital divide

- Leading to financial or economic collapse

- Spurring addiction

- Limiting social development

- Atrophying critical thinking

- Limiting scientific progress through synthetic noise

- Homogenizing culture

- Enabling worker surveillance

- Leading to infrastructure dependency

- Aiding harassment and bullying

- Empowering liberals

- Empowering conservatives

- Fostering digital imperialism and colonialization

- Expanding pornography

- Disorienting people through the speed of change

- Letting corporations avoid accountability

- Powering the surveillance state

- Weakening the family

- Destroying the news business

- Making us poor

- Creating an algorithmic monoculture

- Apparently, even causing Alzheimer’s (a conference panelist once suggested this because we no longer read maps)

And of course: CREATING THE TERMINATOR so that EVERYONE will die (hopefully it spares our pets). Get your affairs in order and prepare to meet your maker.

I could easily compile a list ten times longer of the benefits of digital transformation. But why bother? ITIF and a few other pro-innovation organizations have been documenting those benefits for years. It is like spitting into the wind.

With the shift to a critical culture, evidence becomes superfluous. No one wants to be the uncool kid in the corner talking about the potential of AI adding three-tenths of a percentage point to annual productivity growth. Much better to warn that Open AI will overwhelm the electric grid. Ooooh.

As history shows, culture matters. A critical, rather than supportive, culture produces a business and entrepreneurial class that doubts itself and a society that hesitates rather than seeks faster progress. This should be obvious. If elites—including the intellectual and political classes—are not wholeheartedly behind technological progress and transformation, whether industrial or digital, progress will inevitably be more halting and less successful.

In a world where America faces intense international competition in the digital space, especially from China, this is a cultural posture we adopt at our peril.

This is a two-part blog. In the first installment, I examine the role culture played in industrial development and economic progress through England’s experience. It relies predominantly on Martin Wiener’s 2004 book, English Culture and the Decline of the Industrial Spirit, 1850-1980, which anyone interested in industrial development should read. Wiener’s heavily documented thesis is that although “England was the world’s first great industrial nation… the English have never been comfortable with industrialization,” that discomfort ultimately contributed to industrial weakness and decline.

Wiener argues that after roughly 40 or 50 years of support and enthusiasm at the dawn of English industrialization, Britain never quite seemed culturally “at home” with progress. Ultimately, this anti-industrial sentiment contributed to the decline of British industry and the “modern fading of national economic dynamism.”

England’s state of mind, like that of much of the United States today, was profoundly conservative in the sense of preserving the past while remaining skeptical of, or openly hostile to, the present and future.

According to Wiener, the English genius “was not economic or technical, but social and spiritual; it did not lie in inventing, producing or selling, but in preserving, harmonizing and normalizing.” He goes on to note that Britain’s greatest task—and achievement—lay in “taming and ‘civilizing’ the dangerous engines or progress it had unwittingly unleashed.”

English society did tame those engines, and in doing so, tamed the entrepreneurial spirits that sought to push forward and keep their country in the lead. Meanwhile, other nations, including the United States, Germany, and later Japan, got on with the task of unleashing and surged ahead.

But today, America is in the process of leashing itself. States compete to regulate first and most aggressively. Pundits rush to see who can write the harshest critique of our “digital dystopia.” Members of Congress battle to decry the harms of AI and introduce restrictive legislation.

So why did England invent the machine but then become ambivalent at best, and hostile at worst, toward industrialization? Wiener writes that “modernization has never been a simple and easy process. Wherever and whenever it has occurred, severe psychological and ideologic strains have resulted.” English elites resisted those strains, much as American elites do today. I wish “resistance is futile,” but in Britain’s case, it was not. It was effective. They made less progress and grew more feeble.

To be sure, there were a few dissenters who resisted the elite narrative. But not many. As Wiener notes, “Rarely were these canons challenged, and then only by self-possessed ‘rugged individualists’ who had a strong sense of swimming against the tide.”

Every day in America, fewer seem willing to swim against the tide. It is easier to retreat to the shore and observe—or better yet, turn to the preservation and fund massive anti-digitalization and anti-Big Tech campaigns, as so many guilt-ridden, cashed-out tech billionaires have done.

So what, you may ask? America is still the digital leader. But as Wiener reminds us, ideas have consequences. How could they possibly not? England was still the manufacturing leader as late as the 1880s and 1890s. Yet by then, English politics reflected deep ambivalence about industrial society and, in practice, helped dampen rather than stimulate industrial development. These widespread cultural values ended up discouraging “commitment to a wholehearted pursuit of economic growth,” explains Wiener.

It should therefore come as no surprise that the UK today is largely an industrial wasteland, with per-capita income roughly 30 percent lower than that of the United States. And, according to the World Happiness Report, English people are no happier for it (or than Americans, for that matter). Cultural ambivalence toward growth and industry carries long-term costs.

It is difficult to overstate the seriousness of this threat to America and the broader West. The culture of digital and AI opposition is one of two major threats to American prosperity and power, the other being the People’s Republic of China’s systematic effort to achieve global domination of national power industries.

It may be asking too much to return to unleashing progress or optimism. But unless U.S. (and allied) culture shifts at least back to neutrality, other nations unburdened by this self-doubt (even self-hatred) and digital fear will progress faster. We can expect to be outpaced and eventually surpassed, just as others once left the UK in the comfortable dust.

I can imagine the U.S. elite class 20 years from now looking at those “materialist,” shallow nations that have completely transformed their education and health care systems with AI, pitying them for losing the “human touch.” Decrying their wealth as environmentally irresponsible. Criticizing our dependence on their digital champions.

Meanwhile, we Americans will congratulate ourselves for preserving our lovely analogue world, reading paperback books, listening to vinyl records, and sending handwritten letters. Let’s hope we don’t revive fax machines, but who knows? Perhaps U.S. elites will turn to carrier pigeons. Owl mail from Harry Potter might be cool—although a “wizarding-adjacent” delivery system would likely be deemed too disruptive, too dystopian, or too innovative.

Critics, of course, defend themselves by arguing that they didn’t change; the internet did. Tim Wu, a longtime Big Tech and telecom critic, states that his new book, The Age of Extraction, “is the story of the last 20 years or so… of the dream of the internet. And then, what happened to wreck it essentially.” For Wu, “wreck” appears to mean an internet that is neither government-owned, worker-co-op-run, nor hacker-managed, yet is used daily by nearly every American and organization. For these digital purists, everything went downhill after Stewart Brand’s email system, The WELL, and the first spam message on ARPANET. Why can’t the internet be like Wikipedia and Craigslist, they ask?

But utopian techno-nurd nostalgia does not fully explain the turn to opposition. Tim and thousands of critics like him are intellectual descendants of the 1960s anti-establishment ethos: If it’s establishment, they’re against it. When Apple was the upstart challenging “Big Brother” IBM, it was cool. Now Apple is evil. When Google was taking on Bill Gates and the Microsoft monopoly, it was cool. Now it’s evil. When OpenAI first challenged Google, it too was cool. Now it is rapidly morphing into the next evil villain. It’s strange how many establishment elites cling to a prideful posture of adolescent anti-establishmentism.

And let’s not forget, Wu wants to be one of the cool kids. Who wouldn’t? Unless, of course, you care more about truth than popularity. If Tim wrote a book called “The Age of Prosperity” rather than The Age of Extraction, it would be met with yawns, not op-eds in The New York Times or The Guardian.

Now multiply this dynamic 10,000 times, across thousands of influential voices eager to join the cool kids club of digital opposition, and you get America’s (and the West’s) corrosive digital culture. In some respects, if one can believe it, Canada, the UK, Australia, and most of Europe are even worse off. These allied nations may be even further down this path, as they rail against both digitalization and American tech—which might help explain their lagging digital productivity growth relative to the United States.

That said, none of this fully explains the rise of an anti-digitalization culture over the last 15 or so years. Perhaps the most compelling explanation is America’s increasing selfishness—what Christopher Lasch termed “the culture of narcissism.” This orientation, which had been brewing since the self-absorption of the 1960s, emerged in full force in the 2010s.

In this mindset, everything is judged not by its collective contribution—what it does for the community or nation, since collective benefits are now dismissed as serving only wealthy elites and powerful corporations—but by its impact on the individual’s narrow self-interests, often in the role of victim rather than citizen.

The long list above of critics about AI reflects this. Is AI going to take my job? Who cares about societal productivity? Is AI going to harm my privacy? Who cares about data innovation? Is AI going to jack up my electric bill? Who cares if AI can make low-income communities safer?

There has almost never been a transformative technology that did not carry risks or cause harm. Automobiles kill people. Electricity causes house fires. Chemicals can cause cancer. Yet earlier generations balanced risk with ambition. Americans had courage and a communitarian spirit, accepting trade-offs in pursuit of national prosperity and progress. They rushed toward technological innovation rather than retreating to the barricades. As Robert Frost put it, “And that has made all the difference.” Today we have cowardice and selfishness, and we rush toward stopping digital innovation.

I wish I could be more optimistic that America will avoid the long, downward path England took. To be sure, the United Kingdom is richer and more technologically advanced than it was 75 years ago. But relative to its peers, it’s a shell of what it should be, underperforming its potential. Unless extremists seize control, which remains possible, the U.S. economy will continue to grow and advance technologically.

But without a fundamental shift in culture, America will gradually decline relative to other nations, ceding leadership. One could easily imagine a world in 2075 where China and India dominate advanced digital industries while the United States is a “pleasant country” with a mid-tier global economy and some “quaint ways.” Those who are 30 years old today will be entering their 80s, looking at their buddies and saying, “Ah, remember when?”

I have no desire to live in that country—one defined by animosity toward technology, fear of innovation, analogue envy, and the techno-economic stagnation that accompanies such attitudes. That is not the America I moved to as a boy from Canada. That is not the America I want for my two children and two grandchildren.

It is late in the game, but it is still not too late to overturn digital pessimism and hostility and recognize them as fundamentally misguided. As Wiener observed of England, it will require many more self-possessed “rugged individualists” willing to swim against the anti-digital tide.

Who wants to join me? The water’s great.

Editors’ Recommendations

Related

January 21, 2025