How NIH-Funded Science Supports US Biopharmaceutical Innovation

NIH-funded research supports the foundation for industry to develop vaccines and therapies, exemplifying deep public-private R&D complementarity. As global competition intensifies, expanding NIH funding will be key to protecting American health, supporting U.S. biopharmaceutical competitiveness, and ensuring national power and security.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Key Takeaways

Contents

The Role of NIH in the Biomedical Innovation Pipeline. 3

Case Studies of NIH-Enabled Breakthroughs 5

Emerging Frontiers for NIH Investment 8

Economic and Strategic Value of NIH. 11

Threats to U.S. Biopharmaceutical Leadership. 14

Introduction

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) is the federal government’s primary agency for biomedical and public health research, and the world’s largest public funder of biomedical research.[1] Established in the early 20th century, NIH has evolved into a network of 27 institutes and centers that support research on a wide range of conditions—from cancer and heart disease to rare genetic disorders and mental health.[2] Each year, NIH invests nearly $50 billion in its own laboratories and in research conducted at more than 2,500 universities, hospitals, and medical centers across the United States.[3]

Crucially, NIH plays a role that is complementary to private-sector research and development (R&D). Public investment supports basic and translational science, which generates the biological insights, targets, tools, and technologies that underlie future medical advances. Pharmaceutical companies then undertake the long, high-risk, and capital-intensive process of turning these early scientific discoveries into safe, effective, and commercially viable medicines. Both sectors are essential, and the United States’ global leadership in biopharmaceutical innovation depends on the strength of this public-private research ecosystem.

NIH is central not only to advancing science but also to sustaining the nation’s biomedical research capacity, supporting the development of homegrown skilled scientific talent and biopharmaceutical innovation. The administration’s proposed FY2026 budget would reduce NIH funding by 40 percent, from roughly $48 billion in 2025 to about $27 billion in 2026—a staggering cut that would also eliminate entire institutes, including the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities and the National Institute of Nursing Research.[4]

As of May 2025, more than 2,100 NIH grants—worth approximately $9.5 billion—had reportedly been terminated.[5] These disruptions are prompting universities to pause hiring, delay clinical trials, and scale back or shut down labs.[6] They also carry serious downstream implications for biopharmaceutical innovation. Modeling studies indicate that a sustained 10 percent reduction in NIH funding could reduce new drug launches by 4.5 percent a year—equivalent to roughly two fewer lifesaving medicines being developed each year.[7]

NIH pursues a dual mission: advancing fundamental knowledge about the nature and behavior of living systems and applying that knowledge to improve health, extend life, and reduce illness and disability.

We understand the Trump administration’s concerns about prior NIH leadership—particularly regarding mishandling certain aspects of its pandemic response and a lack of transparency about the agency’s role in supporting gain-of-function research in Wuhan, China. While the scientific debate over the origins of the COVID-19 remains ongoing, a report from the House Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Pandemic has suggested a Wuhan lab origin, although many involved in NIH-supported virology research have denied this possibility.[8] At the same time, certain NIH-funded institutions’ implementation of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives may, at times, have placed undue weight on identity considerations over merit.[9] But these cases are not universal and should be viewed in context. However, responding to such concerns by punishing NIH and universities by broadly reducing funding for medical research would be counterproductive—harming the American public and economy by slowing lifesaving innovation and reducing high-skilled scientific jobs. Accountability should focus on individuals responsible for past missteps, not on weaking the institutions that underpin U.S. biopharmaceutical leadership.

Sustained investment in NIH is therefore not just a matter of research budgets—it underpins the nation’s ability to accelerate medical breakthroughs, attract and retain top scientific talent, sustain U.S. leadership in the global biopharmaceutical industry amid rising competition, particularly from China, and ensure readiness for future public health and national security threats.

Public funding—as a precursor and complement to biopharmaceutical company investments—is essential for several reasons. It supports foundational research that may not yield immediate commercial returns but can pave the way to major breakthroughs and further incentivize private-sector investment. By funding research without direct commercial application or with high uncertainty, public investment fosters innovation that might otherwise be missed. It can also de-risk early-stage science and encourage private-sector investment.[10]

For example, the Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health’s (ARPA-H’s) mission to address large-scale health challenges mirrors past efforts such as the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency’s (DARPA’s) work to develop the early infrastructure for the Internet and Global Positioning System (GPS) technology. Once that foundation existed, private companies were able to build on it with significant investment—developing applications, scaling the technologies, and bringing commercial products to market. This pattern also applies to the biopharmaceutical innovation ecosystem: public funding provides the basic research groundwork, while industry undertakes the high-risk, capital-intensive work of turning those scientific discoveries into safe and effective therapies. Together, this division of labor shows how public investment can catalyze transformative advances the private sector then develops and commercializes.

The Role of NIH in the Biomedical Innovation Pipeline

NIH anchors America’s biomedical innovation ecosystem, contributing to nearly every modern medical advance through a mix of grant funding, intramural research, and strategic public-private partnerships, and by catalyzing complementary private investment. By sustaining a national research infrastructure that spans universities, hospitals, and industry R&D partners, NIH plays a unique role in turning early-stage scientific discoveries into transformative health innovations that improve health and extend the lives of millions of Americans.[11]

Mandate and Structure

NIH pursues a dual mission: advancing fundamental knowledge about the nature and behavior of living systems and applying that knowledge to improve health, extend life, and reduce illness and disability. The agency is composed of 27 institutes and centers, each focusing on specific areas such as cancer, mental health, and infectious diseases. NIH carries out its mission through two primary research arms. Its Intramural Research Program conducts cutting-edge science within NIH laboratories, which accounts for roughly 11 percent of its budget. Meanwhile, its Extramural Research Program distributes over 80 percent of NIH’s nearly $48 billion annual budget to more than 2,500 institutions, including universities, hospitals, research institutions, and companies across the United States. This dual structure enables NIH to both lead scientific discovery directly and support a broad national research ecosystem, strengthening the nation’s capacity to innovate, train the next generation of scientists, and maintain global biopharmaceutical leadership.[12]

Funding Basic Research

A core strength of NIH lies in its sustained investment in basic biomedical research—foundational studies on cells, genes, immune responses, and disease mechanisms. NIH funding is critical for these studies because they often do not produce immediate commercial applications and are therefore less attractive for private-sector investment. Yet, it provides the essential scientific groundwork on which private R&D can build to develop new medical technologies and therapies.

NIH supports basic research through competitive, peer-reviewed grant mechanisms such as the R01 Research Project Grant, which remains the agency’s primary funding vehicle for investigator-initiated science.[13] A rigorous two-tier review process ensures that public funds support only the most promising and important proposals. This model has delivered extraordinary returns—for example, between 2010 and 2016, NIH-funded research contributed at least some biological, chemical, or molecular insights to the development of all 210 new drugs approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).[14] These contributions occur overwhelmingly at the basic research stage—the early insights into biology and chemistry that open the door to later therapeutic advances. Translating basic scientific insights into safe, effective medicines requires pharmaceutical companies to undertake years of high-risk, capital-intensive R&D—including medicinal chemistry, preclinical work, large-scale clinical trials, manufacturing scale-up, and regulatory submissions. In this way, public and private investments play distinct but complementary roles in the biopharmaceutical innovation ecosystem.[15]

Bridging the Valley of Death

Despite NIH’s successes in advancing biomedical research, early-stage translational research often stalls in the “valley of death”—a high-risk, underfunded stage between laboratory discovery and commercial application. Because industry is reluctant to invest in early-stage basic research projects without clear market potential, many promising breakthroughs risk remaining undiscovered.[16]

Public funding therefore serves as both a precursor and complement to private biopharmaceutical investment. It supports foundational science—such as the basic research behind CRISPR gene editing, the Human Genome Project, and early mRNA platform development—efforts often too uncertain or long term for industry to pursue alone, but that can pave the way to major breakthroughs and further incentivize private-sector investment. By funding high-risk, early-stage research, NIH helps de-risk innovation, stimulate private investment, and ensure that scientific breakthroughs address broad public health needs, enhancing health equity. This role is especially critical in areas such as antimicrobial/antibacterial research, where private investment alone has been insufficient.[17]

NIH directly addresses the valley of death through several targeted efforts. The National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) supports preclinical development and drug repurposing. The Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) programs provide more than $1.4 billion annually in seed funding for biotechnology startups, helping reduce early-stage risk and scale promising technologies.[18]

Such programs supported the early development of successful firms such as Moderna—which leveraged NIH-backed mRNA research and funding for vaccine development—and Ginkgo Bioworks, a synthetic biology firm that leveraged federal SBIR funding to expand its microorganism engineering platform, as well as funding from NIH Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics Advanced Technology Platforms (RADx-ATP) program to expand high throughput SARS-CoV-2 testing during the COVID-19 pandemic.[19] Further, NIH leads the Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSA) program, a national network of roughly 60 hubs that accelerate clinical trials, train translational researchers, and improve development pipeline efficiency, which helped advance discoveries such as Aes-103, a promising sickle cell treatment nearly abandoned in its early stages.[20]

Public funding serves as both a precursor and complement to private biopharmaceutical investment.

Case Studies of NIH-Enabled Breakthroughs

The following are several prominent examples—such as the development of mRNA vaccine platform technologies, the CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing system, and the foundations of targeted cancer therapies—that show how federally supported basic research fuels scientific progress and builds the infrastructure necessary for rapid translation in times of crisis, such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

mRNA Vaccine Platforms

Messenger RNA (mRNA) is a molecule that delivers genetic instructions to cells, teaching them how to produce specific proteins. In vaccines, mRNA can safely allow the body to make a harmless piece of a virus, train the immune system to recognize it, and fight the real threat without using a live virus. NIH-supported scientists began laying the groundwork for mRNA vaccines in the late 1980s, decades before they would help enable the swift response to COVID-19.[21] Researchers first demonstrated that synthetic mRNA encapsulated in lipid droplets could enter cells and direct protein synthesis.

Although the technology showed early promise, it encountered major challenges, including instability, inefficient delivery, and unwanted immune activation. In 2005, Katalin Karikó and Drew Weissman, supported by grants from several NIH institutes, including the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), and the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR), overcame a major hurdle in mRNA research by discovering that substituting uridine with pseudouridine in mRNA strands suppresses innate immune detection. This breakthrough made therapeutic use viable.[22]

Building on this foundation, NIH funding throughout the 2010s advanced lipid nanoparticle (LNP) delivery systems, refined mRNA design, and improved scientists’ structural understanding of viral proteins. These developments allowed companies such as Moderna and BioNTech to establish mRNA vaccine platforms.[23] At the same time, scientists at NIH’s Vaccine Research Center (VRC) collaborated with researchers at the University of Texas at Austin to create a two-proline mutation that stabilizes the coronavirus spike protein.[24] Keeping the spike protein stable in this form allowed mRNA vaccines (like those from Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna) to train the body to mount a strong and precise immune response, improving both the efficacy and safety of the vaccine.

NIH-supported scientists began laying the groundwork for mRNA vaccines in the late 1980s, decades before they enabled the swift response to COVID-19.

After scientists sequenced and published the SARS-CoV-2 genome in January 2020, NIH’s decades of investments proved critical immediately. Within 24 hours, researchers at NIH’s VRC applied the prefusion-stabilizing mutation to the spike protein and partnered with Moderna to encode it in mRNA.[25] This quick application of prior research enabled the development of a highly targeted and effective vaccine candidate, demonstrating how foundational discoveries can rapidly translate into lifesaving therapeutics during a public health crisis. Just 63 days later, the first volunteer was dosed in NIH-led Phase 1 trial of mRNA-1273. As part of its official initiative to accelerate COVID-19 vaccine development, NIH’s National Clinical Trial Networks subsequently led the Phase 3 trials, which demonstrated approximately 95 percent efficacy for both the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines, enabling their emergency use authorizations by December 2020.[26] This success underscores the value of NIH’s sustained commitment to basic molecular biology, translational infrastructure, and public-private collaboration in addressing urgent public health needs.

CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing

The development of CRISPR-Cas9, a powerful genome editing technology, is rooted in decades of federally funded research—much of it supported by NIH. What began in 1987 as a basic scientific observation by Japanese researchers—unusual repetitive DNA sequences in E. coli—sparked curiosity among microbiologists. Over time, scientists uncovered that these sequences were part of a bacterial immune defense system. With sustained NIH funding, researchers were able to explore the underlying mechanisms of this system, ultimately leading to the development of CRISPR-Cas9, a programmable tool for precisely editing genes, and effectively translating the scientific discovery into a biotechnology advance with immense potential.[27] This breakthrough has since revolutionized biomedical research and holds immense potential for treating genetic diseases, demonstrating how long-term public investment in basic science can yield transformative health technologies.

In 2012, scientists Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier successfully reconstituted the CRISPR-Cas9 system in the lab and demonstrated that it could be programmed to cut DNA at precise locations.[28] Shortly thereafter, Feng Zhang and his team at the Broad Institute showed that the system could be used to edit genes in mammalian cells, establishing its feasibility for use in human biology.[29] These NIH-supported studies underscore the critical role of federal support in enabling foundational advances that have gone on to power gene-editing technologies and biotechnology innovation.

Building on foundational discoveries, NIH launched the Somatic Cell Genome Editing (SCGE) program in 2018, committing approximately $190 million to accelerate the safe and effective use of genome editing. The program prioritized improving delivery systems, increasing editing precision, and ensuring safety for clinical use.[30] By focusing on building shared tools and platforms, the SCGE program demonstrated NIH’s role not only as a funder but also as a builder, catalyst, convener, and coordinator of collaborative scientific infrastructure. This ecosystem enabled landmark milestones: in 2019, physicians successfully treated a patient for sickle cell disease with a CRISPR-based therapy that relied on decades of NIH-supported advances in hemoglobin biology and gene transfer.[31]Prominent scientists, including Doudna and Alex Marson, have publicly attributed CRISPR’s success to sustained NIH investments and have warned that future breakthroughs could be jeopardized by budget cuts.[32]

The development of CRISPR-Cas9, a powerful genome editing technology, is rooted in decades of federally funded research—much of it supported by NIH.

NIH has continued advancing genome editing toward clinical use. In 2023, the SCGE program awarded $22 million to a multi-institution research consortium—including the University of California Berkeley, Ohio State University, and University of California San Francisco (UCSF)—to develop in vivo CRISPR therapies for Huntington’s disease and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. The team continues to draw on expertise in genome engineering, neurology, and regulatory science, illustrating NIH’s role in coordinating interdisciplinary research.[33]

Importantly, NIH investments in CRISPR have not been made in response to a particular crisis. Rather, they reflect NIH’s long-term commitment to foundational research and platform technologies—ensuring that the tools, infrastructure, and scientific knowledge are in place when society needs them most.

Targeted Cancer Therapies

The development of targeted cancer therapies also traces back to decades of NIH-funded basic research. In 1960, cancer researchers Peter Nowell and David Hungerford discovered the Philadelphia chromosome—a genetic abnormality found in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).[34] During the 1970s and 1980s, researchers determined that this chromosome resulted from a translocation between two chromosomes, which fused two genes into a single BCR-ABL hybrid gene. Dr. Owen Witte and his colleagues demonstrated that this specific fusion gene causes CML by driving uncontrolled cell growth. Their discovery, supported in part by the National Cancer Institute (NCI), was the first time scientists had linked a specific genetic alteration to human cancer. By pinpointing BCR-ABL, they revealed an actionable molecular target for therapeutic intervention.[35]

In the 1990s, oncologist Brian Druker hypothesized that a drug could inhibit the BCR-ABL protein and selectively eliminate CML cells without harming healthy ones. He collaborated with pharmaceutical scientists from Novartis to screen drug candidates, which ultimately led to the discovery of imatinib (Gleevec), one of the early precision cancer therapies. In 1998, Druker led a clinical trial, partly funded by NIH, to test imatinib in patients with CML. The results showed that leukemia signs vanished in most early-stage patients. Five years later, 98 percent of those patients remained in remission, an outcome rarely seen in oncology.[36] In 2001, the FDA approved Gleevec, transforming CML from a fatal disease into a largely manageable chronic condition. Before Gleevec, only about 30 percent of CML patients survived five years from diagnosis. With Gleevec, that figure rose to 89 percent.[37]

NIH-backed research has enabled a similar targeted therapy breakthrough in breast cancer. In the 1980s, oncologist Dennis Slamon at the University of California Los Angeles, supported by NCI grants, found that 30 percent of breast tumors carried an overactive gene called HER2, which make the cancers grow rapidly and resist standard treatment.[38] Slamon partnered with Genentech (now part of Roche) to develop a therapy that would target this specific mutation in the HER2 gene. Their work led to the development of trastuzumab (Herceptin), a lab-engineered antibody designed to block the HER2 receptor on the surface of cancer cells, preventing it from receiving growth signals. In 1998, Herceptin became the first gene-targeted cancer drug approved for clinical use. Women once given three to five years to live now had some of the highest survival rates among breast cancer patients. Over the last 25 years, Herceptin has saved an estimated 3 million lives globally by precisely targeting HER2-driven tumors.[39] This journey, from basic discovery to targeted therapy, demonstrates the essential role NIH has played in enabling advances in cancer treatment through sustained investment in life sciences research.

Over the last 25 years, Herceptin has saved an estimated 3 million lives globally by precisely targeting HER2-driven tumors.

Emerging Frontiers for NIH Investment

Artificial Intelligence in Drug Development

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) are rapidly reshaping biopharmaceutical innovation, enabling discoveries that were once beyond human analytical capacity. Modern deep learning models can analyze vast datasets—from genomic sequences and medical images to electronic health records—to uncover patterns, predict outcomes, and identify promising therapeutic targets and drug candidates with unprecedented speed and precision.[40]

AI has the potential to accelerate every phase of drug development—from discovery and preclinical testing to clinical trials, regulatory review, and manufacturing. In the discovery stage, AI can rapidly identify promising compounds by analyzing massive chemical and biological datasets, cutting time and cost. During preclinical testing, AI models can simulate complex biological processes to predict how drugs will behave in humans, reducing the need for animal models. In clinical trials, AI can optimize patient selection, improve trial design, and speed data analysis, enabling faster and more reliable results. It can also support regulatory review by helping prepare complex submissions to the FDA and the European Medicines Agency (EMA), potentially shortening review timelines. Finally, in manufacturing and supply chains, AI can boost production efficiency, enhance quality control, and improve demand forecasting. Taken together, these applications could make drug development faster, more efficient, and more responsive to urgent medical needs.[41]

The real-world impact is already evident. In 2020, researchers used a deep learning algorithm to discover halicin, a new antibiotic effective against some of the world’s most dangerous drug-resistant bacteria.[42] The AI system rapidly screened over 100 million molecules and identified a previously unknown antibacterial compound in just days—far faster than traditional laboratory methods. In another breakthrough, DeepMind’s AlphaFold predicted the 3D structures of over 200 million proteins, creating a comprehensive “protein structure universe” that is already transforming drug discovery and biochemical research.[43] Notably, AlphaFold was trained on decades of publicly funded protein data, including NIH-supported protein sequence and structure databases—underscoring how federal investments and public science lay the groundwork for AI-enabled biopharmaceutical innovation.

Despite rapid progress, key challenges remain—particularly around data quality and integration into existing workflows. Biopharmaceutical AI models depend on large, diverse, and carefully curated datasets, yet many existing resources were not originally designed for AI applications. NIH is addressing this challenge through several initiatives. One effort is the All of Us Research Program, launched in 2018. The program has built one of the world’s most diverse genetic data repositories, intentionally including participants historically underrepresented in biomedical research. It also provides accessible, centralized data through a cloud-based research workbench, giving scientists a powerful resource to build more representative and reliable AI-enabled drug development models.[44]

Another effort is NIH’s Bridge to Artificial Intelligence (Bridge2AI) program, launched in 2022. This $130 million NIH Common Fund initiative supports the creation of novel biomedical datasets properly documented and ready for use by AI models, as well as the development of tools to accelerate the production of findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable (FAIR) datasets.[45] Bridge2AI represents NIH’s first major investment in biomedical AI at this scale, enabling the agency’s public funding to drive transformative AI breakthroughs where private-sector investment may be more limited.

By investing in synthetic biology and advanced biomanufacturing, NIH aims to enhance emergency preparedness, enable personalized therapeutics, and scale the production of complex biotechnology products.

Synthetic Biology and Next-Generation Manufacturing

Synthetic biology has emerged as a powerful frontier in biomedical science, enabling researchers to design and construct new biological components or reengineer organisms for useful purposes. Unlike traditional genetic engineering, which typically alters single genes, synthetic biology allows scientists to reprogram entire genetic pathways to produce predictable, programmable behaviors.[46] Researchers are now creating “designer” cells and molecules—such as bacteria that manufacture new antibiotics or selectively target and destroy tumors—and developing cell-based and cell-free systems that act as precise diagnostics or therapeutics. These innovations are opening the door to smart therapeutics that target disease pathways with unprecedented precision and diagnostics that rapidly and sensitively detect disease.[47]

Next-generation manufacturing is translating these discoveries into real-world health solutions. Traditional biomanufacturing—for example, for vaccines or monoclonal antibodies—relies on large, centralized facilities and long production timelines, which often cannot meet urgent or localized demand.[48] As the need for faster, more flexible, and portable biomanufacturing grows, NIH and other agencies are investing in research to close this gap. Synthetic biology breakthroughs are central to this transformation: cell-free systems and engineered microbes now enable the rapid, decentralized manufacture of vaccines, enzymes, and drugs in a matter of days.[49]

To accelerate progress, NIH has partnered with the National Science Foundation (NSF) on initiatives such as BRING (Biomedical Research Initiative for Next-Gen Biotechnologies), which helps turn novel fundamental synthetic and engineering biology advances into practical early-stage biomedical technologies.[50] By investing in synthetic biology and advanced biomanufacturing, NIH aims to enhance emergency preparedness, enable personalized therapeutics, and scale the production of complex biotechnology products.

Pandemic Preparedness and Antimicrobial Resistance

The COVID-19 pandemic underscored the critical role of research infrastructure in enabling the rapid development of vaccines, diagnostics, and therapeutics for emerging infectious threats. To strengthen future preparedness, NIH, particularly through NIAID, has launched major initiatives to counter future outbreaks. One example is the ReVAMPP (Research and Development of Vaccines and Monoclonal Antibodies for Pandemic Preparedness) network, through which NIAID plans to invest up to $100 million annually to advance countermeasures against high-risk virus families. Rather than waiting for the next unknown pathogen, researchers are proactively studying prototype viruses to build the knowledge and tools needed for rapid response, ensuring the development of “safe and effective medical countermeasures before the need becomes critical.”[51]

NIH also plays a vital role in addressing antimicrobial resistance (AMR)—a growing global health and security challenge. Drug-resistant infections directly cause more than 1.27 million deaths each year and contribute to nearly 5 million deaths worldwide. In the United States alone, they lead to more than 2.8 million antibiotic-resistant infections and over 35,000 deaths annually.[52] Yet, despite this escalating threat, new antibiotic development has slowed due to scientific challenges and weak market incentives. Bacteria evolve resistance so quickly that they can outpace the development of new antibiotics, creating a perpetual race between scientific progress and microbial adaptation. Moreover, low financial returns have pushed many pharmaceutical companies out of the antibiotics market, creating a critical gap in the pipeline.[53]

NIH also plays a vital role in addressing AMR—a growing global health and security challenge.

NIH investments help fill this gap by supporting basic and translational AMR research. In addition to traditional antibiotics, researchers are exploring alternative approaches such as bacteriophages and lysins to target resistant bacteria, potentiators to enhance the effectiveness of existing antibiotics, microbiome-based therapies to suppress harmful pathogens, and CRISPR-based methods to selectively remove resistance genes.[54] Through sustained support for early-stage discovery, clinical trials, and new drug development models, NIH strengthens U.S. defenses against future pandemics and drug-resistant “superbugs,” bolstering both national health security and global resilience.

Economic and Strategic Value of NIH

Return on Investment From Public Science

NIH investments provide a powerful engine of economic growth. Over the past decade, NIH funding has generated more than $787 billion in new economic output and supported an average of 370,000 jobs annually across all 50 states.[55] In 2024 alone, NIH awarded approximately $37 billion in research funding, supporting over 408,000 jobs and producing an estimated $94.5 billion in economic activity.[56] Each NIH dollar invested yields roughly $2.50 in short-term economic returns and stimulates an additional $8.30 in long-term private-sector R&D investment—underscoring the strong multiplier effect of public science funding.

Over the past decade, NIH funding has generated more than $787 billion in new economic output and supported an average of 370,000 jobs annually across all 50 states.

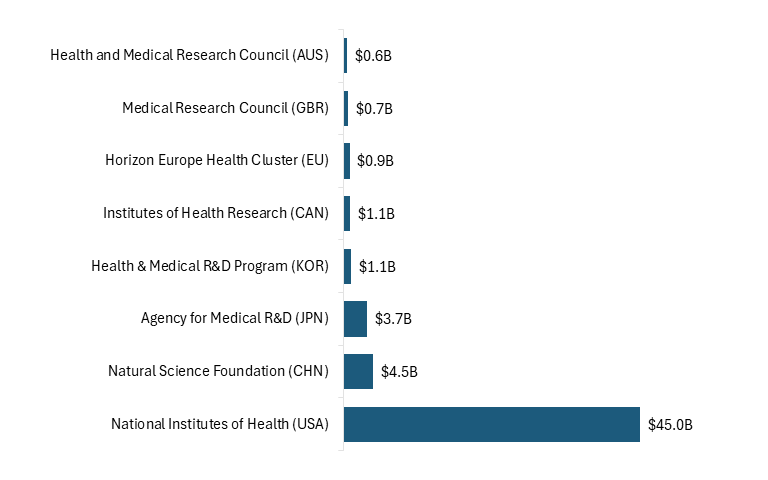

NIH represents a cornerstone of the U.S. innovation economy. NIH funding levels are substantially higher than those of comparable agencies in other countries, underscoring the United States’ dominant role in supporting early-stage biomedical research. (See figure 1.)

Figure 1: Public investment in life sciences R&D, 2022[57]

NIH-backed discoveries fuel commercialization by linking academic research to real-world applications. Approximately 31 percent of NIH grants lead to peer-reviewed research later cited by private-sector patents, and 8 percent contribute directly to patented inventions.[58] As noted, foundational NIH research on mRNA vaccine technology, for example, enabled rapid COVID-19 vaccine development by Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech, while NIH-supported basic science paved the way for breakthrough cancer immunotherapies such as Keytruda, useful in the treatment of melanoma and other forms of cancer.

These innovations spark startup creation, attract private capital, and strengthen the nation’s R&D base, while NIH funding also helps train the next generation of biomedical scientists, seeds regional innovation ecosystems, sustains U.S. biopharmaceutical leadership amid rising global competition, and enhances U.S. soft power through international research partnerships. The return on NIH investments is both immediate and enduring—fueling economic growth today while building the workforce, infrastructure, and resilience needed to sustain U.S. scientific leadership.

Building a Scientific Talent Pipeline

NIH plays a central role not only in funding research but also in sustaining the nation’s biomedical workforce. It supports graduate education, postdoctoral training, and career pathways for more than 300,000 researchers through nearly 50,000 competitive grants across 2,500 universities and research institutions.[59] In FY2024, 34,000 R01-equivalent investigators applied for NIH funding, with about 9,655 receiving awards.[60]

This talent pipeline represents a strategic national asset. A steady flow of skilled biomedical researchers is essential to respond to pandemics, biothreats, and health security challenges. Without sustained federal investment, this talent could be lost to other countries or diverted to different fields, weakening U.S. capacity for innovation and response. Initiatives such as France’s Choose France for Science campaign and the European Union’s Horizon Europe Strategic Plan 2021–2024, which have been explicitly designed to attract top international talent, especially from the United States, pose a risk to the United States’ ability to attract and retain talent.[61] In this competitive environment, sustained NIH support is critical to keep the United States an attractive global hub for world-class biomedical science to ensure that the nation can meet both public health and national security needs.

Catalyzing Regional Innovation Ecosystems

NIH programs such as the Institutional Development Award (IDeA) and its Centers of Biomedical Research Excellence (CoBRE) initiative play a critical role in expanding research capacity across historically underfunded states. IDeA supports 24 states and Puerto Rico through 247 awards totaling nearly $391 million, which help to build infrastructure, support faculty, and advance clinical and translational research across the United States.[62]

NIH programs such as IDeA and its CoBRE initiative play a critical role in expanding research capacity across historically underfunded states.

Examples include Rhode Island (21 awards, $28.6 million), Nebraska (20 awards, $23.9 million), and Oklahoma (19 awards, $34.1 million), which have grown strong regional research hubs anchored in academic research. States such as Nevada (4 awards, $7.2 million), Alaska (3 awards, $5.9 million), and Wyoming (3 awards, $5.8 million) remain at an earlier stage of capacity building—highlighting the importance of sustained and, where necessary, expanded federal support.[63] IDeA plays an important strategic role by distributing resources to underfunded regions, helping to develop a more geographically diverse research capacity and talent pool, and bolstering the entire U.S. biomedical ecosystem. Notably, 83.8 percent of junior investigators supported by CoBRE have gone on to receive a major independent NIH award within five years, demonstrating the program’s strong track record in cultivating research leadership.[64]

CoBRE grants provide sustained, multi-phase funding to help institutions in IDeA-eligible states build innovative biomedical and behavioral research centers. Many grantees—including universities in Nebraska, Oklahoma, and Nevada—have leveraged CoBRE support to launch research hubs, attract private investment, and train local scientific workforces. At the University of Nebraska Medical Center (UNMC), CoBRE funding combined with other federal awards contributed to a record $141 million in research funding in a single year, supporting more than 5,000 jobs in Nebraska.[65]

By distributing resources more equitably and fostering self-sustaining research ecosystems, IDeA and CoBRE grants strengthen U.S. competitiveness, expand the scientific talent pipeline, and enhance the nation’s ability to respond to health challenges.

Strengthening U.S. Competitiveness and National Security

Intensifying global competition in the life sciences—particularly from China—makes sustained NIH investment more critical than ever. Policymakers should view NIH as a strategic pillar of national security, economic growth, and global competitiveness.

China has recently developed a comprehensive national strategy to strengthen its biopharmaceutical innovation capacity, which includes subsidies, financial incentives, high-tech science parks, startup incubators, talent recruitment schemes, regulatory reforms to expedite drug review, enhanced intellectual property protections, and increased science funding. The National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC), the country’s largest public science funder, increased its investment in 2022 to CNY 32.699 billion (about $4.5 billion), up from CNY 31.2 billion ($4.2 billion) the previous year, supporting over 51,000 research projects.[66] As noted, Europe too is advancing through initiatives such as France’s Choose France for Science campaign and the European Union’s Horizon Europe Strategic Plan 2021–2024.[67]

Robust NIH funding amplifies U.S. R&D capacity, while cuts risk ceding leadership to global competitors. NIH investment supports training, infrastructure, and innovation ecosystems that yield downstream competitive advantages—such as biotech clusters, startups, and commercialization—that cannot be replicated quickly by competitors. NIH-backed research underpins hubs such as Boston-Cambridge, home to 1,000 biotech companies and North Carolina’s Research Triangle Park, which employs more than 42,000 individuals.[68]

Finally, NIH is central to national preparedness. Decades of NIH-supported research enabled the rapid development of mRNA vaccines during the COVID-19 pandemic, giving the United States a critical first-mover advantage.[69] Programs such as NIAID’s ReVAMPP are strengthening the nation’s ability to counter future pandemics and biothreats.[70] Sustained NIH investment is therefore essential not only for innovation but also for protecting national security.

Advancing U.S. Global Influence Through Science Diplomacy

NIH is not just a domestic research engine—it is also a key instrument of U.S. science diplomacy. By leading international research collaborations, NIH sets global standards, strengthens U.S. health security, and keeps American firms at the forefront of innovation.

Partnerships in sub-Saharan Africa to combat HIV, in coordination with the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), have saved millions of lives while bolstering U.S. influence in regions where China is expanding its presence.[71] During the COVID-19 pandemic, NIH-backed mRNA research gave the United States a critical geopolitical and scientific advantage.[72] Further, the Fogarty International Center amplifies this influence by training foreign researchers in U.S. scientific methods and standards and embedding American leadership in global networks.[73]

These global initiatives yield strategic returns: faster discovery pipelines, early access to breakthroughs, new jobs in the biopharmaceutical sector, and strengthened geopolitical influence. They also help prevent strategic competitors from shaping the global biopharmaceutical innovation agenda. In a world where health, technology, and power are intertwined, sustaining NIH’s international role is critical to preserving U.S. leadership and strategic advantage.

NIH is not just a domestic research engine—it is also a key instrument of U.S. science diplomacy. By leading international research collaborations, NIH sets global standards, strengthens U.S. health security, and keeps American firms at the forefront of innovation.

Threats to U.S. Biopharmaceutical Leadership

U.S. biopharmaceutical leadership is facing one of its most serious challenges in decades. Proposed deep cuts to NIH funding, paused federal grants, and surging foreign research investment are threatening the foundations of American scientific strength. Without decisive action, the United States risks losing its competitive edge in biopharmaceutical innovation, falling behind on the next generation of breakthrough therapies, and ceding global leadership to strategic competitors.

Proposed Cuts to NIH Funding

NIH is not just a science agency—it represents the backbone of America’s biopharmaceutical innovation ecosystem. It sustains the nation’s research capacity, supports a skilled scientific workforce, and drives medical breakthroughs that power U.S. economic and strategic leadership and protect national security.

The Trump administration’s proposed FY2026 budget would slash NIH funding by approximately 40 percent, from about $48 billion in 2025 to roughly $27 billion in 2026. This unprecedented reduction would eliminate entire institutes—including the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities and the National Institute of Nursing Research—dismantling core infrastructure built over decades.[74]

Already, $1.7 billion in funds have been withheld, and over 2,200 grants totaling $3.8 billion have been canceled, prompting universities to freeze hiring, delay clinical trials, and scale back or shut down laboratories.[75] Modeling studies show that an ongoing 10 percent cut in NIH funding would reduce new drug launches by 4.5 percent annually—the equivalent of losing roughly two new life-saving medicines each year.[76]

The implications are stark: cuts of this magnitude could hollow out America’s biopharmaceutical capacity, disrupt the innovation pipeline, and weaken national preparedness against health emergencies.

Global Competitors Are Rapidly Closing the U.S. Lead

While the United States considers steep NIH cuts, its competitors are dramatically increasing their public science investment. China is closing the R&D gap at unprecedented speed. Between 2019 and 2023, U.S. gross domestic R&D grew by 4.7 percent annually, while China’s grew by 8.9 percent. In 2023, China invested $781 billion in total R&D—nearly matching the U.S. level of roughly $823 billion. Analysts warn that if U.S. science budgets are cut, China could soon overtake the United States in R&D spending.[77]

China’s government has explicitly prioritized science and biotechnology as engines of national power. Under its 14th Five-Year Plan (2021–2025), China committed to increasing R&D investment by more than 7 percent annually and set a goal of raising R&D’s share of gross domestic product (GDP) to about 3 percent. In 2021 alone, China’s basic research investment rose by 10.6 percent—part of a deliberate push to build long-term scientific capacity. Beijing has also launched new national laboratories and innovation centers in strategic fields such as biopharmaceuticals, AI, and genomics.[78]

While the United States considers steep NIH cuts, its competitors are dramatically increasing public science investment. China is closing the R&D gap at unprecedented speed.

In 2022, China unveiled its first Bioeconomy Development Plan, establishing biomedicine as a strategic pillar alongside agriculture and biomanufacturing, with an expected 10 percent annual growth rate in these industries through 2025.[79] By 2023, Chinese government R&D investment on science reached $110 billion—far exceeding the $65 billion spent by the U.S. government on intramural research.[80] In short, China is channeling massive public funds into biopharmaceutical innovation to position itself as a global science leader by 2035—a trajectory that directly challenges U.S. leadership.

The European Union is also stepping up investment in health and science. In 2021, the EU launched Horizon Europe—its largest-ever R&D framework program—with a budget of €95.5 billion ($110.4 billion) for 2021–2027, up from €77 billion ($89 billion) in 2020.[81] The program includes a dedicated health cluster to support collaborative research on cancer, infectious diseases, health technologies, and more. The EU has also created targeted initiatives such as the European Health Emergency Preparedness and Response Authority (HERA) and EU4Health to bolster resilience and innovation capacity.[82]

Major member states are also pursuing their own ambitious national strategies. Germany is steadily increasing its science budget to reach 3.5 percent of GDP by mid-decade, and France’s Choose France for Science, part of France 2030, aims to attract top international scientific talent.[83] Collectively, the 27 EU member states account for about one-fifth of global R&D spending across all fields of science and technology. Although the United States still invests more in biomedical R&D than does any single country, Europe’s coordinated investment commitments are signaling a more competitive global landscape.[84]

Beyond China and the EU, other nations are also intensifying R&D investment. South Korea is now one of the leading countries in R&D spending, allocating over 5 percent of GDP to R&D.[85] Large family-owned conglomerates (chaebols) and the government are channeling significant resources into biotechnology, pharmaceuticals, and medical devices, fueling advances in cell therapy and vaccine development. Meanwhile, Japan supports one of the world’s largest public biotech research agencies, the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED), and has launched moonshot programs in regenerative medicine and AI-enabled drug discovery. India and other emerging economies are also expanding biomedical R&D, particularly in genomics and vaccine research.[86]

As a result, the global biopharmaceutical innovation landscape is far more crowded and competitive than it was a decade ago. Collectively, foreign public-sector investments now match or exceed U.S. levels. While NIH’s annual budget in recent years has exceeded $40 billion, this once-unmatched level of investment is no longer exceptional, and in 2024, the National Academy of Medicine noted that the rest of the world is rapidly catching up.[87]

This surge in international investment poses clear and immediate risks to U.S. leadership in biopharmaceutical innovation. If current trends continue, researchers and entrepreneurs abroad may increasingly produce the breakthrough discoveries that define the next generation of medicines. Other countries may outspend and out-hire U.S. institutions, eroding long-held U.S. advantages in drug development, genomics, and clinical research. Leadership in high-value markets, including novel cancer therapies and mRNA technologies, could shift toward Asia or Europe.[88]

The United States cannot rely on other nations’ basic research to sustain its own biopharmaceutical progress. Nations invest in life sciences to advance their own strategic, economic, and national security interests—not to serve as a public good for global competitors. Dependence on foreign investment would leave the United States reliant on other governments—some of them geopolitical rivals—for the scientific foundations of future medicines, vaccines, and technologies. It could also erode U.S. leadership in shaping global research priorities, regulatory standards, and the institutional excellence that underpins biopharmaceutical innovation. In a world where science is central to economic strength and national power, outsourcing basic research would amount to outsourcing America’s future competitiveness.

Without renewed policy commitment and sustained NIH investment, the United States risks forfeiting its scientific, economic, and strategic leadership position.

In a future global health crisis, nations investing more heavily in science may lead in vaccine and therapeutic development, leaving the United States in a reactive rather than proactive position. Countries that drive biomedical advances will set global standards, attract international collaboration, and shape innovation agendas, giving them significant geopolitical leverage. Without renewed policy commitment and sustained NIH investment, the United States risks forfeiting its scientific, economic, and strategic leadership position.[89]

Risk of Overreliance on Private-Sector and Philanthropic Funding

While global competitors are intensifying their public R&D support, the United States has proposed cuts. Budget increases for NIH have barely kept pace with inflation in recent years, and in FY2024, funding declined for the first time in a decade, to $47.3 billion—an 0.8 percent drop from 2023.[90] Adjusted for biomedical inflation, the NIH budget now has roughly the same purchasing power as it did two decades ago and remains below its 2003 peak following the early-2000s doubling, from $13 billion in 1998 to over $27 billion by 2003.[91]

In the meantime, private industry and philanthropy have filled part of the gap: by 2012, private industry had provided about 58 percent of total U.S. biomedical R&D funding, compared with 42 percent from public sources (primarily NIH).[92] Large philanthropies such as the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the Fred Hutch Cancer Center, and the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research have become especially influential.

While private and philanthropic investments are critical, they cannot substitute for public funding. Public agencies such as NIH have historically supported a broad, balanced portfolio of science—including high-risk, high-reward areas with no immediate commercial application—guided by public health priorities and peer review. By contrast, private investors focus on projects with near-term commercial applications, shifting the focus toward specific drug development rather than open-ended basic research exploration. In 2022, the top 20 pharmaceutical firms invested a combined $139 billion in R&D, much of it directed toward late-stage drug development rather than foundational research.[93] Over time, these dynamics skew the national research agenda toward short-term innovation, leaving foundational science that can provide the building blocks for next-generation breakthroughs underfunded.

While private and philanthropic investments are critical, they cannot substitute for public funding.

Many transformative health innovations—from the Human Genome Project to mRNA vaccine technology—originated in basic research. Such long-horizon, high-uncertainty work depends on sustained public funding. The Union of Concerned Scientists has notes that “basic science … requires sustained investment and a lot of patience because its benefits might not be apparent for decades.”[94] Private-sector R&D rarely supports such research, and even philanthropic donors may favor projects aligned with their interests or those offering more predictable outcomes. Heavy reliance on nongovernmental funding therefore puts the scientific discovery pipeline itself at risk.

Public funding provides the engine that powers long-term innovation. It supports foundational research; it de-risks early-stage innovation, creating opportunities for private-sector investment; it ensures that scientific agendas align with public health priorities; and it sustains work in underserved fields, such as AMR, where private investment is often insufficient. In short, public funding is not just complementary to private investment—it is indispensable. A biopharmaceutical innovation system built too heavily on private capital risks narrowing the scope of research, slowing the pace of discovery, and leaving critical public health needs unmet.

Recommendations

Sustain and Expand NIH Funding

NIH investments are both a health and economic imperative. Sustained NIH funding supports new industries, treatments, and jobs in communities across the country, and is critical to U.S. global competitiveness. Yet, federal science investment as a share of GDP has fallen to just 0.6 percent, far below the nearly 2 percent levels of the 1960s, while other countries are dramatically increasing their investment.[95] Strong, sustained NIH funding is essential to preserving America’s leadership in biopharmaceutical innovation, retaining top scientific talent, and sustaining the pipeline of medical breakthroughs. Policymakers should treat NIH funding as a strategic national priority and grow it at the rate of nominal GDP growth each year at least.

Basic research—the exploratory, early-stage science that expands fundamental knowledge—is the foundation of all biopharmaceutical innovation. Cutting it creates false savings: applied science and commercial innovation cannot thrive without the discoveries that basic science generates. Though its payoff takes time, steady support sustains the innovation pipeline and keeps U.S. science globally preeminent.

If opportunities decline, top U.S.-based scientists have warned that they will move their labs abroad.[96] Other countries are actively recruiting them, and when they produce breakthroughs, Europe or Asia—not the United States—will reap the benefits. This “brain drain” would weaken America’s scientific capacity and long-term innovation strength.

Policymakers should treat NIH funding as a strategic national priority and grow it at the rate of nominal GDP growth each year at least.

The economic consequences would be profound. A 25 percent reduction in federal research funding could slow the U.S. economy on a scale comparable to the Great Recession, while the long-term loss of scientific leadership would be incalculable.[97]

Basic science is a public good: it expands knowledge, produces unexpected breakthroughs, and underpins the applied research that industry pursues. As global competitors make strategic investments in science, the United States cannot afford to cede leadership in foundational research. Maintaining robust NIH funding is essential to America’s health, economy, and global competitiveness.

Incentivize Public-private Partnerships

Public-private partnerships can accelerate medical innovation by combining public scientific leadership with industry resources and expertise. NIH’s Accelerating Medicines Partnership—a collaboration among NIH, the FDA, pharmaceutical companies, and nonprofits—illustrates this model, working together to combat diseases such as Alzheimer’s, diabetes, and rheumatoid arthritis. Industry partners contribute roughly 25 percent of project costs and share data, while NIH provides core scientific leadership.[98] Similar collaborations have helped deliver breakthroughs such as the rapid co-development of mRNA vaccines during the COVID-19 pandemic. Policymakers such as Congress, NIH, and the FDA can encourage such partnerships through matching grants, translational research consortia, and data-sharing initiatives.

Improve Public Communication of NIH’s Impact

Despite its vast contributions to society, NIH’s role in improving public health is not widely understood. Public trust in science has eroded: by 2023, only 57 percent of Americans believed science had a mostly positive effect on society—a 16 percentage point drop since before the pandemic.[99] Strengthening NIH’s science communication efforts could help rebuild trust and sustain bipartisan support. To this end, NIH should translate complex science into clear, accessible narratives that highlight its real-world impact. Plain-language research summaries, patient stories, educational programs, and medical campaigns could show how NIH-funded research improves lives—from cancer immunotherapies to vaccines.[100] Collaborations with schools, libraries, and community organizations could promote science literacy and dialogue, and help make science part of everyday conversation. These efforts could be supported through modest, targeted outreach funds within NIH’s existing communications budget or through competitive grants that encourage community-based engagement. By clearly connecting NIH research to public benefit, the agency could foster durable public support, counter misinformation, and strengthen its legitimacy. Universities could also be required to identify NIH support in public announcements of research breakthroughs, improving visibility into the agency’s role.

Conclusion

NIH represents a cornerstone of U.S. strength in the biopharmaceutical industry. Its investments in basic scientific research generate early discoveries in biology and physiology, providing the foundation that industry builds on to develop novel vaccines and therapies—a relationship that exemplifies the deep complementarity between public and private R&D.

Eroding this foundation through funding cuts would weaken U.S. competitiveness and resilience at a time when other nations are accelerating their own research investments. Sustained—and ideally expanded—NIH support is essential to maintain America’s biopharmaceutical leadership, protect national security, and secure long-term health and economic prosperity.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Robert Atkinson and Stephen Ezell for helpful feedback on this report. Any errors or omissions are the authors’ sole responsibility.

About the Authors

Sandra Barbosu is associate director of ITIF’s Center for Life Sciences Innovation. She is also adjunct professor at New York University’s Tandon School of Engineering. She holds a Ph.D. in Strategic Management from the Rotman School of Management at the University of Toronto, and an M.Sc. in Precision Cancer Medicine from the University of Oxford.

Sarina Fereydooni is a life sciences fellow with ITIF’s Center for Life Sciences Innovation. She focuses on the intersection of health, science, and policy. She is currently pursuing a B.A. in Political Science and a certificate in Global Health at Yale University.

About ITIF

The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) is an independent 501(c)(3) nonprofit, nonpartisan research and educational institute that has been recognized repeatedly as the world’s leading think tank for science and technology policy. Its mission is to formulate, evaluate, and promote policy solutions that accelerate innovation and boost productivity to spur growth, opportunity, and progress. For more information, visit itif.org/about.

Endnotes

[1]. “About NIH,” National Institutes of Health, https://www.nih.gov/about-nih.

[2]. Kavya Sekar, Congressional Research Service, National Institutes of Health (NIH) Funding: FY1996–FY2025, Report No. R43341 (June 2024), https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/R43341.pdf.

[3]. “Grants & Funding,” National Institutes of Health (January 2025), https://www.nih.gov/grants-funding.

[4]. Richard G. Frank, “The 2026 health and health care budget” (Brookings Institution, June 2025), https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-2026-health-and-health-care-budget/.

[5]. Karen Feldscher, “Documenting grant cancellations that represent ‘a life’s worth of work’,” Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health (May 2025), https://hsph.harvard.edu/news/documenting-grant-cancellations-that-represent-a-lifes-worth-of-work/.

[6]. Andrew Matthius, “Senate Forum Examined the Ramifications of NIH Funding Cuts,” Cancer Research Catalyst (AACR Blog), April 16, 2025, https://www.aacr.org/blog/2025/04/16/senate-forum-examined-the-ramifications-of-nih-funding-cuts/.

[7]. Kritika Agarwal, “NIH Funding Cuts Will Result in Fewer Drugs Coming to Market, CBO Finds,” Association of American Universities, July 25, 2025, https://www.aau.edu/newsroom/leading-research-universities-report/nih-funding-cuts-will-result-fewer-drugs-coming.

[8]. “House panel concludes that COVID-19 pandemic came from a lab leak,” Science (December 2024), https://www.science.org/content/article/house-panel-concludes-covid-19-pandemic-came-lab-leak.

[9]. John D. Sailer, “A Death Knell for Diversity Statements,” City Journal, March 25, 2025, https://www.city-journal.org/article/a-death-knell-for-diversity-statements.

[10]. Sandra Barbosu, “Harnessing AI to Accelerate Innovation in the Biopharmaceutical Industry” (ITIF, November 2024), https://itif.org/publications/2024/11/15/harnessing-ai-to-accelerate-innovation-in-the-biopharmaceutical-industry/.

[11]. “Grants & Funding,” National Institutes of Health.

[12]. “NIH Data Book,” National Institutes of Health (January 2025), https://report.nih.gov/nihdatabook/report/.

[13]. “Research Project (R01)”, NIH Grants & Funding, National Institutes of Health (January 2025), https://grants.nih.gov/funding/activity-codes/R01.

[14]. Ekaterina G. Cleary et al., “Contribution of NIH Funding to New Drug Approvals 2010–2016,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences vol. 115, no. 10 (2018): 2329–2334, https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.1715368115.

[15]. Barbosu, “Harnessing AI to Accelerate Innovation in the Biopharmaceutical Industry.”

[16]. Ibid.

[17]. Ibid.

[18]. “Understanding SBIR and STTR,” NIH SEED, National Institutes of Health, https://seed.nih.gov/small-business-funding/small-business-program-basics/understanding-sbir-sttr.

[19]. “NIH-Moderna Investigational COVID-19 Vaccine Shows Promise in Mouse Studies,” National Institutes of Health (May 18, 2020), https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/nih-moderna-investigational-covid-19-vaccine-shows-promise-mouse-studies; “Gingko Bioworks Awarded $40MM RADx-ATP Contract to Expand High Throughput SARS-CoV-2 Testing,” PR Newswire (July 31, 2020), https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/ginkgo-bioworks-awarded-40mm-nih-radx-atp-contract-to-expand-high-throughput-sars-cov-2-testing-301104121.html.

[20]. “About the CTSA Program,” NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health (September 2025), https://ncats.nih.gov/research/research-activities/ctsa.

[21]. “Decades in the Making: mRNA COVID-19 Vaccines,” NIH National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health (April 2024), https://www.niaid.nih.gov/diseases-conditions/decades-making-mrna-covid-19-vaccines.

[22]. Katalin Kariko et al., “Suppression of RNA Recognition by Toll-like Receptors: The Impact of Nucleoside Modification and the Evolutionary Origin of RNA,” Immunity, vol. 23, no. 2 (2005): 165–175, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1074761305002116; Declan Butler, “Translational Research: Crossing the Valley of Death,” Nature vol. 453, no. 7197 (2008): 840–842, https://www.nature.com/articles/453840a.

[23]. “For mRNA, COVID Vaccines Are Just the Beginning,” Wired, April 18, 2022, https://www.wired.com/story/for-mrna-vaccines-covid-was-just-the-beginning/.

[24]. “Breakthrough Coronavirus Research Results in New Map to Support Vaccine Design,” The University of Texas at Austin Department of Molecular Biosciences, February 19, 2020, https://molecularbiosci.utexas.edu/news/research/breakthrough-coronavirus-research-results-new-map-support-vaccine-design; Marc Airhart, “COVID-19 Vaccines with UT Ties Arrived Quickly After Years in the Making,” The University of Texas at Austin Department of Molecular Biosciences, July 15, 2020, https://molecularbiosci.utexas.edu/news/research/covid-19-vaccines-ut-ties-arrived-quickly-after-years-making.

[25]. Kizzmekia S. Corbett et al., “SARS-CoV-2 mRNA Vaccine Design Enabled by Prototype Pathogen Preparedness,” Nature 586 (2020): 567–571, https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-020-2622-0.

[26]. “Moderna Announces Primary Efficacy Analysis in Phase 3 COVE Study for Its COVID-19 Vaccine Candidate and Filing Today with U.S. FDA for Emergency Use Authorization,” Business Wire, November 30, 2020, https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20201130005506/en/Moderna-Announces-Primary-Efficacy-Analysis-in-Phase-3-COVE-Study-for-Its-COVID-19-Vaccine-Candidate-and-Filing-Today-with-U.S.-FDA-for-Emergency-Use-Authorization.

[27]. Yoshizumi Ishino, Mart Krupovic, and Patrick Forterre, “History of CRISPR-Cas from Encounter with a Mysterious Repeated Sequence to Genome Editing Technology,” Journal of Bacteriology, vol. 200, no. 7 (2018): 10–1128, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29358495/.

[28]. Meilin Zhu, “Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier’s Experiment About the CRISPR/cas9 System’s Role in Adaptive Bacterial Immunity, ASU Embryo Project Encyclopedia, October 19, 2017, https://embryo.asu.edu/pages/jennifer-doudna-and-emmanuelle-charpentiers-experiment-about-crisprcas-9-systems-role-adaptive.

[29]. “Broad Institute-MIT team identifies highly efficient new Cas9 for in vivo genome editing,” Broad Institute, April 1, 2015, https://www.broadinstitute.org/news/broad-institute-mit-team-identifies-highly-efficient-new-cas9-vivo-genome-editing; F Ann Ran et al., “Genome engineering using the CRISPR-Cas9 system,” Nature Protocols, vol. 8 (2013): 2281–2308, https://www.nature.com/articles/nprot.2013.143.

[30]. Krishanu Saha et al., “The NIH Somatic Cell Genome Editing program,” Nature, vol. 592 (2021): 195–204, https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-021-03191-1.

[31]. Kevin Davies, Alex Philippidis, and Rodolphe Barrangou, “Five Years of Progress in CRISPR Clinical Trials (2019-2024),” The CRISPR Journal vol. 7, no. 5 (2024): 227–230, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39436279/.

[32]. Jennifer Doudna and Alex Marson, “Federal funding for basic research led to the gene-editing revolution. Don’t cut it.” Vox, April 22, 2017, https://www.vox.com/the-big-idea/2017/4/22/15392912/genes-science-march-nih-funding-basic-research-doudna.

[33]. “$22 million NIH award will accelerate ‘CRISPR’ research at UC Berkeley, Ohio State,” The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, June 27, 2023, https://wexnermedical.osu.edu/mediaroom/pressreleaselisting/nih-crispr-award.

[34]. Peter C. Nowell, “Discovery of the Philadelphia Chromosome: A Personal Perspective,” Journal of Clinical Investigation vol. 117, no. 8 (2007): 2033–2035, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1934591/.

[35]. “How Imatinib Transformed Leukemia Treatment and Cancer Research,” National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health (April 2018), https://www.cancer.gov/research/progress/discovery/gleevec.

[36]. Ibid.

[37]. Brian J. Druker et al., “Five-Year Follow-Up of Patients Receiving Imatinib for Chronic Myeloid Leukemia,” New England Journal of Medicine vol. 355, no. 23 (2006): 2408–2417, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17151364/; Leslie A. Pray, “Gleevec: the Breakthrough in Cancer Treatment,” Nature Education, vol. 1, no. 1 (2008): 37, https://www.nature.com/scitable/topicpage/gleevec-the-breakthrough-in-cancer-treatment-565/.

[38]. Dennis J. Slamon et al., “Human Breast Cancer: Correlation of Relapse and Survival with Amplification of the HER-2/neu Oncogene,” Science, vol. 235, no. 4785 (1987): 177–182, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3798106/.

[39]. “25 Years of Herceptin®: A Groundbreaking Advancement in Breast Cancer Treatment,” UCLA Health News, October 18, 2023, https://www.uclahealth.org/news/release/25-years-herceptin-groundbreaking-advancement-breast-cancer.

[40]. Barbosu, “Harnessing AI to Accelerate Innovation in the Biopharmaceutical Industry.”

[41]. Ibid.

[42]. Ian Sample, “Powerful Antibiotic Discovered Using Machine Learning for First Time,” The Guardian, February 20, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/feb/20/antibiotic-that-kills-drug-resistant-bacteria-discovered-through-ai.

[43]. Linda Geddes, “DeepMind Uncovers Structure of 200M Proteins in Scientific Leap Forward,” The Guardian, July 28, 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2022/jul/28/deepmind-uncovers-structure-of-200m-proteins-in-scientific-leap-forward.

[44]. Barbosu, “Harnessing AI to Accelerate Innovation in the Biopharmaceutical Industry.”

[45]. “NIH Launches Bridge2AI Program to Expand Use of Artificial Intelligence in Biomedical and Behavioral Research,” National Institutes of Health, October 19, 2022, https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/nih-launches-bridge2ai-program-expand-use-artificial-intelligence-biomedical-behavioral-research.

[46]. “NOT-EB-23-002: Notice of Special Interest: Synthetic Biology for Biomedical Applications, National Institutes of Health, April 14, 2023, https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-EB-23-002.html.

[47]. Tian Gao et al., “Sonogenetics-Controlled Synthetic Designer Cells for Cancer Therapy in Tumor Mouse Models,” Cell Reports Medicine vol.5, no. 5 (2024), https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38608697/.

[48]. Chenwang Tang et al., “On-Demand Biomanufacturing Through Synthetic Biology Approach,” Materials Today Bio (2022), https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9830231/.

[49]. Aidan Tinafar, Katariina Jaenes, and Keith Pardee, “Synthetic Biology Goes Cell-Free,” BMC Biology vol. 17, no. 1 (2019): 64, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6688370/.

[50]. “Biomedical Research Initiative for Next-Gen BioTechnologies (BRING-SynBio),” NSF Funding Opportunity, National Science Foundation, https://www.nsf.gov/funding/opportunities/bring-synbio-biomedical-research-initiative-next-gen-biotechnologies.

[51]. Darren Incorvaia, “NIH Establishes Pandemic Preparedness Network, Announces $100M Yearly Funding for Development,” Fierce Biotech, September 18, 2024, https://www.fiercebiotech.com/research/nih-establishes-pandemic-preparedness-network-announces-100m-yearly-funding-development.

[52]. “Antimicrobial Resistance: Data & Research – Highlights,” CDC, February 4, 2025, https://www.cdc.gov/antimicrobial-resistance/data-research/facts-stats/index.html#:~:text=Highlights.

[53]. Mark A. T. Blaskovich and Matthew A. Cooper, “Antibiotics Re-Booted—Time to Kick Back Against Drug Resistance,” npj Antimicrobials & Resistance vol. 3, no. 1 (2025), https://www.nature.com/articles/s44259-025-00096-1.

[54]. Jayaseelan Murugaiyan et al., “Progress in Alternative Strategies to Combat Antimicrobial Resistance: Focus on Antibiotics,” Antibiotics vol. 11, no. 2 (2022), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8868457/.

[55]. “UMR Releases Annual NIH Economic Impact Report: 2025 Update,” United for Medical Research, March 2025, https://www.unitedformedicalresearch.org/statements/umr-releases-annual-nih-economic-impact-report-2025-update/.

[56]. Sy Boles, “NIH Funding Delivers Exponential Economic Returns,” Harvard Gazette, March 11, 2025, https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2025/03/nih-funding-delivers-exponential-economic-returns/.

[57]. NIH, https://www.aip.org/fyi/2022/nih-budget-fy22-outcomes-and-fy23-request; China’s National Natural Science Foundation, https://www.nsfc.gov.cn/english/site_1/pdf/NSFC%20Annual%20Report%202022.pdf; Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development, https://www.amed.go.jp/content/000145346.pdf; Korea Ministry of Health and Welfare Health & Medical R&D Program, https://www.mohw.go.kr/board.es?act=view&bid=0027&list_no=369052&mid=a10503010100&tag=0; Canadian Institutes of Health Research, https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/53661.html; European Commission's Horizon Europe - Health Cluster, https://www.ukro.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/factsheet_heu_cluster_1_May-2025-Update.pdf; UK’s Medical Research Council, https://www.ukri.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/UKRI-02082023-8563-UKRI-Annual-Report-2022-23-Acc.pdf; Australian National Health and Medical Research Council, https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/reports/Annual%20reports/Annual-Report-2022-23.pdf.

[58]. Peter Dizikes, “Study: NIH Funding Generates Large Numbers of Private-Sector Patents,” MIT News, March 30, 2017, https://news.mit.edu/2017/study-nih-funding-generates-large-numbers-private-sector-patents-0330.

[59]. “Budget, Research for the People,” National Institutes of Health, June 13, 2025, https://www.nih.gov/about-nih/organization/budget.

[60]. “RePORT NIH Data Book,” National Institutes of Health, January 2025, https://report.nih.gov/nihdatabook/category/14.

[61]. “Choose France for Science: launch of the dedicated platform for applications to host international researchers,” Republique Francaise, April 17, 2025, https://anr.fr/en/latest-news/read/news/choose-france-for-science-launch-of-the-dedicated-platform-for-applications-to-host-international-r/; Horizon Europe Strategic Plan 2021 – 2024, Directorate General for Research and Innovation, 2021, https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/horizon_europe_strategic_plan_2021-2024.pdf.

[62]. IDeA Interactive Portfolio Dashboard, NIH National Institute of General Medical Sciences, https://www.nigms.nih.gov/Research/DRCB/dashboard/IDeA.

[63]. Ibid.

[64]. Michael D. Schaller, “Efficacy of Centers of Biomedical Research Excellence (CoBRE) grants to build research capacity in underrepresented states,” The FASEB Journal vol., 38, no. 6 (2024): e23560, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37577479/.

[65]. John Keenan, “UNMC research continues to reach new levels,” University of Nebraska Medical Center, November 1, 2024, https://www.unmc.edu/newsroom/2024/11/01/unmc-research-continues-to-reach-new-levels/.

[66]. Sandra Barbosu, “How Innovative Is China in Biotechnology?” (ITIF, July 2024), https://www2.itif.org/2024-chinese-biotech-innovation.pdf.

[67]. “Choose France for Science: launch of the dedicated platform for applications to host international researchers,” Republique Francaise; Horizon Europe Strategic Plan 2021 – 2024, Directorate General for Research and Innovation.

[68]. “Boston is the Largest Biotech Hub in the World,” EPM Scientific, February 2023, https://www.epmscientific.com/en-us/industry-insights/career-advice/boston-is-the-largest-biotech-hub-in-the-world; “A Global Life Science Hub,” Work in the Triangle, https://www.workinthetriangle.com/working-here/key-industries/life-sciences/.

[69]. “Decades in the Making: mRNA COVID-19 Vaccines,” National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, April 2024, https://www.niaid.nih.gov/diseases-conditions/decades-making-mrna-covid-19-vaccines.

[70]. “NIH awards establish pandemic preparedness research network,” National Institutes of Health: Turning Discovery Into Health, September 13, 2024, https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/nih-awards-establish-pandemic-preparedness-research-network.

[71]. “The United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief,” U.S. Department of State, https://www.state.gov/pepfar/.

[72]. “Decades in the Making: mRNA COVID-19 Vaccines,” National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

[73]. Fogarty International Center, https://www.fic.nih.gov.

[74]. Richard G. Frank, “The 2026 health and health care budget” (Brookings Institution, June 2025), https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-2026-health-and-health-care-budget/.

[75]. Andrew Matthius, “Senate Forum Examined the Ramifications of NIH Funding Cuts,” Cancer Research Catalyst (AACR Blog), April 16, 2025, https://www.aacr.org/blog/2025/04/16/senate-forum-examined-the-ramifications-of-nih-funding-cuts/.

[76]. Agarwal, “NIH Funding Cuts Will Result in Fewer Drugs Coming to Market, CBO Finds.”

[77]. Trelysa Long, “China Is Catching Up in R&D — and May Have Already Pulled Ahead” (ITIF, April 2025), https://itif.org/publications/2025/04/09/china-catching-up-rd-may-have-already-pulled-ahead/.

[78]. “China’s 14th Five-Year Plan (2021–2025) and Its Impact on Your IP Portfolio,” JD Supra, August 4, 2021, https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/china-s-14th-five-year-plan-2021-2025-7673093/.

[79]. Xu Zhang et al., “The roadmap of bioeconomy in China,” Engineering Biology, vol. 6, no. 4 (2022): 71–81, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9995158/

[80]. Long, “China Is Catching Up in R&D — and May Have Already Pulled Ahead.

[81]. “Horizon Europe,” Health-NCP-Net, https://www.healthncp.net/horizon-europe.

[82]. “About the Horizon Europe – Health Programme,” European Health and Digital Executive Agency (HaDEA), European Commission, https://hadea.ec.europa.eu/programmes/horizon-europe/health/about_en.

[83]. “Tomorrow’s Innovations: Expenditure on Research and Development,” Institute for Economic Structures Research (GWS), April 17, 2025, https://www.gws-os.com/en/the-gws/news/detail/our-figure-of-the-month-05-2025

[84]. “Cross-National Comparisons of R&D Performance, Science and Engineering Indicators” (National Science Foundation), https://ncses.nsf.gov/pubs/nsb20203/cross-national-comparisons-of-r-d-performance.

[85]. “Research and development expenditure as a share of GDP in South Korea from 1976 to 2023,” Statista, https://www.statista.com/statistics/1326558/south-korea-randd-spending-as-share-of-gdp/.

[86]. The State of the U.S. Biomedical and Health Research Enterprise: Strategies for Achieving a Healthier America (Washington DC: The National Academies Press, 2024), Ch. 3, https://nap.nationalacademies.org/read/27588/chapter/5.

[87]. Congressional Research Service, “National Institutes of Health (NIH) Funding: FY1996–FY2025,” June 25, 2024, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/R43341.pdf.

[88]. “U.S. Investments in Medical and Health R&D 2016–2020,” Research!America (January 2022), https://www.researchamerica.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/ResearchAmerica-Investment-Report.Final_.January-2022-1.pdf.

[89]. The State of the U.S. Biomedical and Health Research Enterprise: Strategies for Achieving a Healthier America.

[90]. Congressional Research Service, “National Institutes of Health (NIH) Funding: FY1996–FY2025.”