EU Should Improve Transparency in the Digital Services Act

The implementation of the Digital Services Act’s transparency obligations fails to provide meaningful insight into online platforms’ content moderation decisions, the extraterritorial effects of the act, and its effects on online speech.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Key Takeaways

Contents

Content Moderation and Transparency 4

Introduction

Regulating media to protect consumers while respecting free expression has always been a delicate balancing act. From the invention of the printing press, which made books accessible to the masses, to the advent of radio and television, which brought live entertainment into people’s homes, policymakers and industry stakeholders have grappled with how to facilitate the dissemination of information and entertainment while limiting the spread of illegal and harmful content.

To date, no media technology has posed a more complex challenge for both government and industry than social media. Social media allows billions of people around the world to publish information and communicate with others. This unprecedented communications channel has kick-started important social and political movements, connected users with distant friends and family, facilitated the spread of knowledge and ideas, and brought endless entertainment to anyone with an Internet-connected device. However, while social media has undoubtedly transformed society in many positive ways, it has also exacerbated existing challenges and introduced new ones by making it easier than ever to create and spread harmful or illegal content. Moreover, a lack of agreement about what content is harmful makes content moderation decisions politically charged.

Thus, content moderation is one of the key challenges social media platforms have to grapple with in today’s globally interconnected online ecosystem. Complicating this further, different governments have taken different approaches to regulating online content, and platforms that offer their services in multiple jurisdictions (i.e., most online services) must comply with all these different regulations. Businesses then must make difficult trade-offs between tailoring their services to each jurisdiction’s rules and standardizing their practices as much as possible across jurisdictions, leading the strictest set of rules to take precedent.

The EU’s DSA is one of the most ambitious content moderation regulatory frameworks developed to date.[1] The law applies to social media and other online platforms offering services within the EU. Conceived to “create a safer digital space where the fundamental rights of users are protected,” the DSA establishes strict content moderation for illegal content, as well as accountability and transparency requirements.[2]

The DSA’s transparency requirements focus on illuminating platforms’ existing practices. Specifically, Article 17 of the DSA requires online platforms to provide “a clear and specific statement of reasons” each time they remove or restrict content that is illegal or violates a platform’s terms of service.[3] Platforms must submit these statements of reasons to the European Commission’s DSA Transparency Database, which offers tools for the public to access, analyze, and download those statements.[4] This transparency requirement has multiple benefits. First, it helps to avoid infringing on users’ free speech rights. Second, it allows regulators and researchers to measure the scope and effectiveness of different platforms’ content moderation practices. Third, it contributes toward efforts to measure the extent of harmful and illegal content and activity online. Finally, it encourages accountability in the form of fairer and more effective content moderation by making platforms’ actions public.

This report focuses on social media platforms, a subset of online platforms that host a large quantity and variety of user-generated content. This feature of social media, as well as certain platforms’ individual content moderation decisions, has generated controversy and global debate over whether platforms effectively balance preventing harm, including to users, while safeguarding free speech. Many policymakers believe platforms have not struck the right balance, leading to regulation such as the DSA.

Unless the EU makes changes to the reporting requirements, other countries will have little insight into the potential extraterritorial impact of the law on free speech or the extent to which the EU is imposing its own speech regulations on the rest of the world.

The report also explores the impact of the DSA’s transparency requirements on social media content moderation within and outside the EU and the effectiveness of these requirements at providing adequate insight into social media content moderation. In order to do so, the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) extracted data from the DSA Transparency Database and then processed this dataset using Python Pandas within a Jupyter Notebook environment.

First, this report explains the DSA’s content moderation and transparency provisions, which require online platforms to remove illegal content—including content that violates EU law or the laws of any individual member state—and submit statements of reasons for content moderation decisions, among other measures, and explores the effect these requirements have had in Europe and may have on the rest of the world. Next, it explains the methodology used to evaluate data from the DSA Transparency Database. Then, it presents the findings and analysis from this data, including a lack of important information regarding the types of content social media platforms have restricted or removed and whether those content moderation decisions applied outside the EU.

Ultimately, this report shows that the EU DSA’s transparency reporting obligations fail to provide meaningful insight into the impact of the DSA on free speech online, both in the EU and abroad. Unless the EU makes changes to the reporting requirements, other countries will have little insight into the potential extraterritorial impact of the law on free speech or the extent to which the EU is imposing its own speech regulations on the rest of the world. This report offers recommendations for the EU to improve the transparency provisions within the DSA. The European Commission should:

▪ replace vague content removal rationales, such as “scope of platform service,” with clear and specific categories;

▪ separate the category of “illegal or harmful speech” into two categories, “illegal speech” and “harmful speech”;

▪ require online platforms to indicate whether they restricted or removed content for violating European law, including the laws of individual member states, or a separate provision in the platform’s terms of service; and

▪ require online platforms to include information in their statements of reasons on whether they also applied their content moderation decisions in the EU outside the EU.

Content Moderation and Transparency

Virtually every online platform, including social media, has terms of service, or a list of rules users must agree to follow in order to use the platform. Typically, these terms include community guidelines that outline content and behavior that is forbidden on the platform, such as depictions of graphic violence, threats of violence, sexually explicit content, promotion of harmful behavior (e.g., eating disorders, self-harm, and suicide), hate speech (as defined by the platform), spam, and more.

Community guidelines vary from platform to platform depending on the community the platform wants to foster. For example, a social media platform geared toward an adult audience might have fewer restrictions on sexually explicit content than one geared toward a general audience. Additionally, a platform that prioritizes a more curated online experience might engage in stricter moderation practices than one that prioritizes unrestricted free speech. This freedom of platforms to determine their own rules, within legal boundaries, is important to maintaining a diverse online world. If every platform had to adopt the same community guidelines, users would have less freedom to choose how to express themselves online.

The negative impact on free speech is the primary weakness of regulations that would prescribe certain moderation practices for social media platforms. In contrast, regulations that focus more on providing transparency in content moderation aim to address problems of online safety and fairness in content moderation without placing limits on users’ freedom of expression. Rather than dictating platforms’ terms of service or community guidelines, these regulations would instead give insight into how and why platforms make certain content moderation decisions. Regulators can use analysis of this information to hold platforms accountable for enforcing their terms of service and community guidelines fairly across the board.

The DSA’s transparency requirements—including those in Article 17, which lays out requirements for transparency surrounding content moderation practices—are an example of this approach. First, by requiring social media and other online platforms to provide clear and easily accessible terms and conditions, the DSA aims to ensure that users understand each platform’s community guidelines. Second, by requiring platforms to submit statements of reasons—information about individual content moderation decisions, including specific actions taken and reasons behind taking those actions—and annual reports on content moderation decisions, the DSA aims to provide insight into platforms’ moderation practices. Third, by requiring platforms to provide certain information about advertisements, the DSA aims to allow consumers to make informed purchasing decisions. And finally, by requiring platforms to provide certain information about their algorithms, the DSA aims to dispel some of the uncertainty around how and why platforms promote certain content and deprioritize other content.

If every platform had to adopt the same community guidelines, users would have less freedom to choose how to express themselves online.

Taken together, these measures could help increase impartiality in content moderation, which would ideally increase users’ trust in social media platforms. These measures could also increase safety by providing policymakers and stakeholders with greater insight into the challenges social media platforms face and methods they utilize when addressing harmful or illegal content and activity.

The Digital Services Act

The DSA is an EU regulation that went into effect in 2022 and applies to all online platforms, including social media networks, e-commerce marketplaces, app stores, and other digital service providers. The DSA exempts online platforms from legal liability for third-party content if they adhere to certain requirements. It also includes transparency and safety obligations for online platforms.

The stated goal of the DSA is to make the online world a safer, more predictable, and more trustworthy place by placing obligations on online platforms, including by:

▪ removing illegal content upon receiving an order to do so from a European judicial or administrative authority;

▪ providing information to the authorities on specific users that the platform has already collected upon receiving an order to do so;

▪ providing clear, plain, intelligible, user-friendly, and unambiguous terms and conditions that are publicly available and easy to access;

▪ providing annual reports on content moderation practices;

▪ creating mechanisms for users to report illegal content and responding to those notices by removing the content if the information and allegations within the notice are accurate;

▪ providing a statement of reasons for removing or restricting content and suspending, banning, or restricting a user’s account;

▪ notifying the authorities of suspected offenses that are criminal within the EU;

▪ avoiding deceptive or manipulative interface design;

▪ providing certain information about advertisements on the platform;

▪ providing certain information about algorithms on the platform;

▪ ensuring a high level of privacy, safety, and security for minors; and

▪ imposing additional requirements for “very large online platforms,” including risk assessments, crisis response mechanisms, independent audits, additional advertising transparency, and annual “supervisory fees” paid to the European Commission.

Transparency Requirements

The DSA’s transparency requirements for content moderation are contained in Article 17. This section of the DSA requires social media and other online platforms to “provide a clear and specific statement of reasons” when restricting the visibility of content (including removal), suspending or terminating monetization of content, or suspending or terminating a user’s account.[5]

The statement of reasons must contain certain information, including which measures the platform took regarding the content (e.g., removal, demonetization, account suspension), why the platform took those measures, whether an automated process found or removed the content, and options for the user to appeal the content moderation decision.[6] The DSA Transparency Database collects these statements of reasons in a publicly accessible format, meaning platforms’ moderation decisions—at least in the EU—are visible not only to regulators but also to the general public within and outside the EU.

Before the DSA, social media and other online platforms were not required to provide transparency around their content moderation decisions. Some platforms had already established voluntary transparency measures, such as Google’s Transparency Report, or oversight measures, such as Meta’s Oversight Board, but these measures are not universal.[7] The so-called “black box” of content moderation has raised concerns over safety and fairness: Are social media platforms doing enough to remove illegal content and content that violates their terms of service?[8] And are they enforcing their terms and conditions in a uniform way?

Increased transparency surrounding content moderation is one way to address these concerns, and Article 17 of the DSA is the first major attempt to implement such measures via regulation. If it is successful in increasing transparency and trust in social media platforms, countries outside Europe may want to replicate the DSA’s approach, because while the DSA’s content moderation rules may have an extraterritorial impact, its transparency provisions only apply to content moderation decisions in the EU.

Global Impact

Although the DSA is an EU regulation, its effects have the potential to impact other countries due to the global nature of many social media and other online platforms. Large online services, in particular—such as social media and e-commerce platforms—often operate in multiple regions and must comply with many different countries’ laws. As a result, these platforms may choose to apply certain DSA standards globally to maintain consistency and simplify compliance across markets. This raises concerns over regulatory overreach, regulatory imperialism, and the extraterritorial application of the DSA.

Regulatory overreach occurs when laws in one jurisdiction reach into other regions, sometimes unintentionally and sometimes by design. The DSA does not require platforms to take down illegal content outside the EU, meaning platforms could simply disable content that is illegal in certain countries only in those countries while leaving it up for users in other countries. However, social media platforms may choose to apply the DSA’s relatively strict approach to content moderation globally to simplify compliance, thereby impacting users outside the EU. For example, they could remove or restrict content that would be allowed in non-EU regions, thus affecting global content availability and user experience. Content moderation aside, the DSA applies to all online platforms that offer their services in EU countries. Moreover, with its additional requirements for “very large online platforms,” the DSA targets predominantly American firms, effectively punishing them for their success.

EU policymakers and proponents of the DSA maintain that the law does not censor speech.[9] But many U.S. policymakers, global companies, and civil society organizations have their doubts.[10] A 2024 report by the Future of Free Speech, a nonpartisan think tank, finds that, under the DSA, “Legal online speech made up most of the removed content from posts on Facebook and YouTube in France, Germany, and Sweden.”[11] Depending on the sample, between 87.5 percent and 99.7 percent of deleted comments were legally permissible, with Germany having the highest percentage of deleted legal speech. Additionally, a 2025 report by House Judiciary Committee Republicans finds that the DSA was forcing companies to change their global content moderation policies and targeted political speech, humor, and satire.[12]

While the United States has led the world in technological innovation, Europe has taken a different road by leading the world in technological regulation.

Regulatory imperialism describes one country’s or region’s outsized influence on other countries’ policies. In the case of the EU, this is known as the Brussels effect. In part due to a lack of American action and leadership on digital policy, and in part due to the EU’s extraterritorial regulation—including the DSA—many countries have modeled their own tech regulations after Europe’s. Via the Brussels effect, the EU has taken a global lead on certain digital policy issues, exporting its approach outside its borders and even into the United States.[13]

While the United States has led the world in technological innovation, Europe has taken a different road by leading the world in technological regulation. This is a symptom of Europe’s precautionary approach to innovation driven by fears—mostly unfounded—of technology’s potential negative impact on society.[14] This means that, in most cases, the Brussels effect has been a net negative for the United States’ pro-innovation approach to digital policy.

Regardless of the effectiveness of the DSA’s transparency requirements, the United States should remain cautious when it comes to the law’s other provisions, of which extraterritorial application could have implications for free speech in the United States and beyond. Europe’s restrictions on speech are stricter than the United States’, and if social media platforms use the EU’s standard for content moderation outside the EU for the sake of simplified compliance, this will affect American and global users’ ability to express themselves freely online.

The current Trump administration has raised concerns over the DSA’s potential impact on free speech multiple times. In February 2025, President Donald Trump signed a memorandum directing his administration to “prevent the unfair exploitation of American innovation” and named the DSA as one of many actions by foreign governments that would face scrutiny.[15] Then in May 2025, the State Department sent letters requesting “examples of government efforts to limit freedom of speech,” including the DSA, which one State Department official categorized as part of “the global censorship-industrial complex.”[16]

Methodology

For this research, ITIF extracted data from the DSA Transparency Database, focusing on a 24-hour span of content moderation actions taken on July 31, 2024. The dataset, originally in CSV format, was substantial, containing millions of rows. To manage the large volume of data, ITIF merged all CSV files into a single dataset and then processed this dataset using Python Pandas within a Jupyter Notebook environment.

The key data points analyzed include the following:

▪ Platform name: Which platform removed the content?

▪ Content type: What type of content was removed (e.g., text, image, video)?

▪ Category of statement of reasons: What category does the reason for content removal or restriction fall under (e.g., hate speech, privacy violation)?

▪ Decision visibility: What decision was made regarding the visibility of the content (e.g., removed, disabled, demonetized)?

▪ Decision on account: What actions were taken concerning the account that posted the content (e.g., suspension, account removal)?

▪ Automated detection: Was the content flagged by automated detection systems?

▪ Automated decision: Was the content moderation decision made by an automated system?

▪ Source type: Was the content removed voluntarily by the platform or in response to a notice?

This range of metrics provided a comprehensive view of content moderation actions across multiple platforms.

ITIF ran a statistical analysis of content removal trends based on statements, breaking down this data by platform to see which services were most active in content moderation, whether content moderation decisions were driven by internal platform policies or external legal frameworks, the type of content most frequently targeted by content moderation decisions, and the level of automation involved in detecting and removing content.

Results

ITIF’s analysis of the DSA Transparency Database indicates a number of trends in content moderation decisions and their impact across different platforms. These key patterns relate to categories of restricted content, types of decisions, and automation or human consideration.

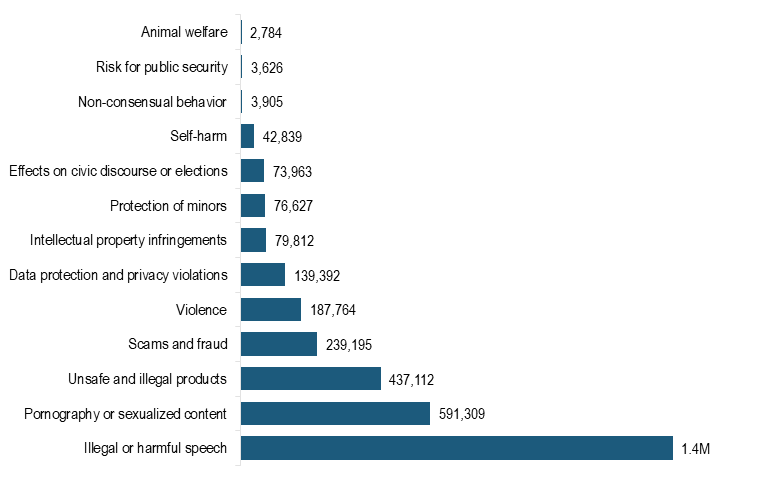

Figure 1: Categories of online platforms’ statements of reasons (excluding “scope of platform service”)

Online platforms had several categories to choose from when selecting the reason content was restricted or removed. Unfortunately, many platforms chose the vague category “scope of platform service.” Platforms can choose this category when the platform decides that the moderated content violates its community guidelines or terms of service, such as content in an unsupported language, involving nudity, or referring to prohibited goods or services. Given the variety of reasons contained within this category, including overlap with other categories, it provides little insight into what rule or law the content violated.

Figure 1 charts those statements that were for a more specific category, revealing that “illegal or harmful speech” was by far the most common reason platforms restricted or removed content, indicating the potential effect the DSA has on online speech. For example, certain content is illegal in certain European countries that is not illegal in other countries, including the United States—such as Holocaust denial in Germany. Additionally, there is a major difference between illegal speech and speech that is legal but considered harmful. The latter category often requires highly subjective analysis on issues for which reasonable people’s opinions can differ. Pornographic content, unsafe or illegal products, scams and fraud, and violent content also made up significant portions of content restricted or removed; however, these categories carry fewer free speech concerns. Content judged to have a negative effect on civic discourse or elections, another category with strong ties to free speech, made up a relatively small portion of content restricted or removed.

Across all online platforms, the most common response to problematic content was to disable the content rather than remove it entirely (see figure 2). The ability of platforms to disable content only in certain locations allows platforms to adhere to country- or region-specific rules, including the DSA, without impacting the availability of that content worldwide. The prevalence of disabling rather than removing content is a promising signal that social media platforms may not apply the EU’s content rules around the world.

However, when it comes to content containing illegal or harmful speech, online platforms overwhelmingly removed the content rather than disabling or otherwise restricting it, with these decisions representing over 98 percent of decisions made regarding this type of content (see figure 3). Since there is no data in the DSA Transparency Database to indicate whether platforms removed content for violating their own terms of service rather than European law, it is difficult to determine the impact of the DSA and other European regulations on global content moderation and online free speech.

Figure 2: Decisions online platforms made regarding content visibility

Figure 3: Decisions online platforms made regarding content containing illegal or harmful speech

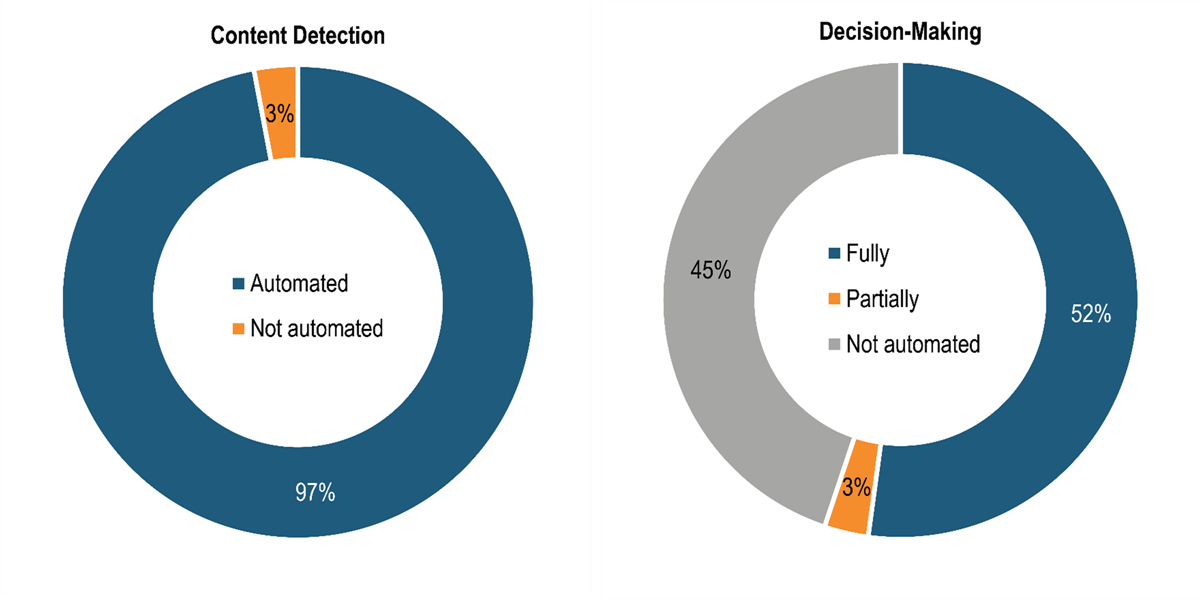

Finally, online platforms provided information in their statements of reasons on the extent to which automated tools played a role in content detection and removal. Ninety-seven percent of content detection was automated and over half of content removal decisions were fully automated, indicating a high level of automation in content moderation (see figure 4). This approach has some major benefits, as well as potential risks. Automated content detection and removal is faster and cheaper than human moderation and avoids issues that might stem from human bias. But it also prevents human moderators from being repeatedly exposed to horrific violent or sexually graphic content that can cause serious negative mental health impacts.[17]

Since there is no data in the DSA Transparency Database to indicate whether platforms removed content for violating their own terms of service rather than European law, it is difficult to determine the impact of the DSA and other European regulations on global content moderation and free speech.

However, automated tools can miss important context that human moderators might be more likely to catch, which may lead platforms to remove content that is not problematic or miss content that is problematic.[18] Ideally, as technology advances, these tools will become increasingly sophisticated, reducing concerns over accuracy and reliability. However, there is likely no way to ensure that content moderation is 100 percent accurate, regardless of whether platforms use human moderators, automated tools, or a combination of both, especially since many content moderation decisions are highly subjective and reasonable people can disagree as to the best way to respond to certain content.

Figure 4: Online platforms’ use of automated content detection and decision-making (57.4 million decisions sampled on July 31, 2024)

There were multiple barriers to drawing detailed conclusions based on the data contained in the DSA Transparency Database, primarily related to a lack of detail in that data. While it is important to both consider the burden transparency requirements may pose on social media and other online platforms and avoid imposing overly burdensome requirements, it is equally important to ensure that transparency requirements do what they set out to do: in this case, provide insight into social media platforms’ content moderation practices.

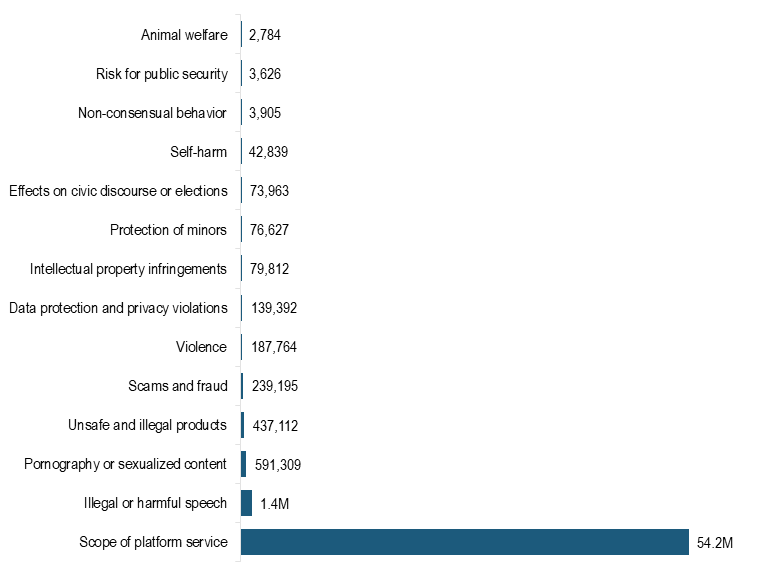

The first barrier was vague categorization. When categorizing why platforms restricted or removed content, the overwhelming majority—nearly 90 percent—of statements fell into the category labeled “scope of platform service” (see figure 5). This incredibly vague category includes any content that the online platform submitting the statement forbids according to its terms and conditions and community guidelines, and thus encompasses many different categories of content and types of harm, from violence and nudity to hate speech and election misinformation. ITIF excluded these statements from its analysis due to their vagueness.

Figure 5: Categories of online platforms’ statements of reasons

The second barrier was a lack of information as to what actions platforms took that affected users outside the EU. Platforms were only required to state which countries within the EU were affected by content moderation decisions. Given that the vast majority of affected content violated platforms’ terms of service, it would stand to reason that platforms removed or restricted this content globally and not only within the EU; however, the DSA Transparency Database does not provide this information. Thus, analysis of the DSA Transparency Database alone cannot answer questions regarding potential extraterritorial application of the DSA.

Finally, a barrier ITIF encountered in its research that has since been resolved was the lack of an application programming interface (API) that researchers could use to analyze the data within the DSA Transparency Database. The European Commission made such an API available in February of 2025, after ITIF had concluded its data collection.[19] While ITIF was still able to analyze the data from within a 24-hour period using third-party tools, it will be easier going forward for other researchers to analyze DSA transparency data.

Previous research supports ITIF’s findings that the DSA’s transparency mechanisms are insufficient. For example, a 2025 study by researchers from Italy finds inconsistencies between the DSA Transparency Database and VLOPs’ (Very Large Online Platforms’) transparency reports.[20] A separate 2024 study by researchers from the Netherlands finds that the database allows platforms to “remain opaque on the grounds behind content moderation decisions,” particularly for content moderation decisions based on terms of service infringements.[21] The report claims that “platforms can strategize their use of the database as a means to show their compliance, even though in practice it may be insufficient.”[22]

Despite these barriers, the data within the DSA Transparency Database provided some insight into content moderation trends in Europe. Above all, it revealed a large variation of content moderation patterns and priorities between different social media platforms. This variation is a key feature of the digital ecosystem for multiple reasons. First, it provides users with a variety of different online experiences to choose from, from heavily moderated spaces that prioritize a specific user experience to more lightly moderated spaces that prioritize free speech. Second, it promotes competition between social media platforms. If a social media platform changes how it moderates content in a way that some users do not like, those users can move to another platform that more closely aligns with their wants and needs.

While it is important to consider the burden transparency requirements may pose on social media and other online platforms and avoid imposing overly burdensome requirements, it is equally important to ensure that transparency requirements do what they set out to do.

Therefore, it is crucial that regulation of social media platforms preserve platforms’ ability to tailor their own content moderation practices to the user base they wish to cultivate. If every platform were forced to abide by a strict set of moderation practices, consumers would have limited choices and smaller or emerging social media platforms would have fewer ways to attract new users by differentiating themselves from existing, dominant platforms.

The data within the Transparency Database also revealed that platforms proactively and voluntarily moderate the vast majority of content. In other words, social media and other online platforms primarily restrict or remove content that their own human moderators, automated systems, or users flag and report, rather than waiting to receive a takedown notice or government order (see figure 6). Mainstream platforms do not want to host illegal content or other content that violates their terms of service, not only to avoid liability for the content, but also to avoid harming their users and damaging their own reputation among users and advertisers. Most users do not want to use platforms that are riddled with harassment, violence, hate speech, scams, and exploitation. Likewise, most companies do not want advertisements for their products and services to appear alongside these types of content.

Figure 6: Sources of online platforms’ content restriction or removal

While these trends of variety on content moderation and voluntary removal of problematic content are encouraging, partial or inconsistent reporting, vague categorization, and a complete lack of data on the extraterritorial effects of content moderation in the EU indicate significant room for improvement. Transparency requirements are ineffective at best and superfluous at worst if they do not fully reveal important information about platforms’ practices. Reforms to these requirements would facilitate increased trust and accountability across the digital ecosystem.

Recommendations

In order to provide true transparency into social media platforms’ content moderation practices in the EU, the European Commission should reform the DSA transparency requirements to address challenges posed by partial or inconsistent reporting, vague categorization, and a lack of data on the extraterritorial effects of the DSA. There are four specific and relatively minor reforms that would solve these problems.

First, the European Commission should remove the statement category “scope of platform service” for online platforms reporting why they restricted or removed certain content. This category is vague and unhelpful in providing transparency into platforms’ content moderation practices, and the DSA cannot meaningfully accomplish true transparency in content moderation as long as the vast majority of statements fall into this category as they currently do. If needed, the European Commission should also expand the list of categories platforms can choose from when reporting why they restricted or removed content if the current categories do not cover the breadth of platforms’ reasons. These new categories should be specific enough to illuminate the specific European law or platform policy the content violated.

Second, the European Commission should separate the category of “illegal or harmful speech” into two categories—“illegal speech” and “harmful speech”—as the free speech implications of each are very different. Illegal speech is defined by law, and online platforms are obligated to remove it under the DSA, whereas harmful speech is a subjective category not defined in the DSA that platforms are not required to remove but often choose to remove. Reasonable people can disagree on what constitutes “harmful speech,” and when platforms remove too much speech—including speech that is merely controversial—they have deemed “harmful,” free speech suffers.

Third, the European Commission should require online platforms in their statements of reasons to indicate whether platforms restricted or removed content for violating European law or a separate provision in the platforms’ terms of service. Combined with the first reform, this would indicate to researchers and policymakers the extent to which the DSA impacts content moderation in the EU. If platforms would already remove certain content for violating their terms of service, then the DSA likely has little impact on the availability of that content. However, if platforms are more motivated by European law than by their own policies, then global policymakers and free speech advocates may have more cause for concern.

Fourth, the European Commission should require online platforms in their statements of reasons to include information on whether their content moderation decisions in the EU, such as restricting or removing content or banning or suspending users, were also applied outside the EU. For example, if a platform removes content containing hate speech that is illegal in certain European countries but legal in other countries such as the United States, did it remove that content globally, or can users in non-European countries still see it? These are the kinds of decisions that have the biggest potential to negatively impact free speech around the world. The rest of the world should not be subject to European laws.

The European Commission should reform the DSA transparency requirements to address challenges posed by partial or inconsistent reporting, vague categorization, and a lack of data on the extraterritorial effects.

Together, these four changes would solve the lack of adequate transparency in the DSA. Requiring more detailed reasons from platforms as to why they made certain content moderation decisions would allow governments and researchers to track trends in content moderation in the EU in greater detail, informing policy decisions and hopefully increasing users’ trust in those platforms. Additionally, platforms would no longer be wasting their own time and resources submitting statements of reasons that provide only a limited amount of transparency.

Meanwhile, requiring platforms to reveal the global impact of their content moderation decisions in Europe would shed light on concerns of regulatory overreach and extraterritorial impact. If the data reveals that the DSA and other EU laws do impact the types of content that are available to users worldwide, other countries could take steps to mitigate that impact. If, on the other hand, the data does not show such an impact—either because platforms are removing content only in Europe while maintaining its availability elsewhere or because platforms would remove that content regardless because it violates their terms of service—then the EU can dispel and disprove concerns of extraterritorial impact. Until then, the lack of data will continue to fuel concerns and create friction between the EU and other parts of the world.

Conclusion

Analysis of data from the DSA Transparency Database reveals some positive trends in content moderation in the EU, such as variety among social media platforms’ content moderation practices and proactive rather than reactive content moderation. However, there are multiple barriers in this database that prevent in-depth analysis of content moderation trends in Europe, the DSA’s impact on free speech, and its potential extraterritorial impact. The European Commission could address these barriers with relatively minor changes to the DSA, which would ensure true transparency as well as address concerns over the DSA’s potential impact on global content moderation.

About the Authors

Ash Johnson is a senior policy manager at ITIF specializing in Internet policy issues including privacy, security, platform regulation, e-government, and accessibility for people with disabilities. Her insights appear in numerous prominent media outlets such as TIME, The Washington Post, NPR, BBC, and Bloomberg. Previously, Johnson worked at Software.org: the BSA Foundation, focusing on diversity in the tech industry and STEM education. She holds a master’s degree in security policy from The George Washington University and a bachelor’s degree in sociology from Brigham Young University.

Puja Roy was a Google Public Policy Fellow at ITIF working at the intersection of technology, policy, and data analysis. She has a computer science and engineering background and her expertise includes web development, data science, AI, and machine learning. Puja previously interned at NASA, LinkedIn, American Express, CVS Health, NOAA, and the MTA. She is currently pursuing her master’s in Data Science at CUNY School of Professional Studies and has a bachelor’s degree in Computer Engineering Technology from CUNY New York City College of Technology.

About ITIF

The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) is an independent 501(c)(3) nonprofit, nonpartisan research and educational institute that has been recognized repeatedly as the world’s leading think tank for science and technology policy. Its mission is to formulate, evaluate, and promote policy solutions that accelerate innovation and boost productivity to spur growth, opportunity, and progress. For more information, visit itif.org/about.

Endnotes

[1]. Regulation (EU) 2022/2065 of the European Parliament and of the Council of October 19, 2022 on a Single Market For Digital Services and amending Directive 2000/31/EC (Digital Services Act).

[2]. “The Digital Services Act package,” European Commission, accessed March 5, 2025, https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/digital-services-act-package.

[3]. Regulation (EU) 2022/2065 (Digital Services Act), Article 17.

[4]. “DSA Transparency Database,” European Commission, accessed March 5, 2025, https://transparency.dsa.ec.europa.eu/?lang=en.

[5]. Regulation (EU) 2022/2065 (Digital Services Act), Article 17.

[6]. Ibid.

[7]. “Google Transparency Report,” Google, accessed August 18, 2025, https://transparencyreport.google.com/?hl=en; “Oversight Board,” Oversight Board, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.oversightboard.com/.

[8]. See, for example, Renée Diresta et al., “It’s Time to Open the Black Box of Social Media,” Scientific American, April 28, 2022, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/its-time-to-open-the-black-box-of-social-media/.

[9]. See, for example, Anda Bologa, “Are Europe’s Speech Rules Censorship? No.”, CEPA, March 12, 2025, https://cepa.org/article/are-europes-speech-rules-censorship-no/.

[10]. See, for example, Claire Pershan, “DSA not a tool for censorship: Demanding clarity from EU Commissioner,” Mozilla Foundation, July 26, 2023, https://www.mozillafoundation.org/en/blog/the-dsa-is-not-a-justification-for-censorship/.

[11]. “Preventing ‘Torrents of Hate’ or Stifling Free Expression Online?” (The Future of Free Speech, May 2024), https://futurefreespeech.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Preventing-Torrents-of-Hate-or-Stifling-Free-Expression-Online-The-Future-of-Free-Speech.pdf.

[12]. The Foreign Censorship Threat: How the European Union’s Digital Services Act Compels Global Censorship and Infringes on American Free Speech (Committee on the Judiciary of the U.S. House of Representatives, July 2025), https://judiciary.house.gov/sites/evo-subsites/republicans-judiciary.house.gov/files/2025-07/DSA_Report%26Appendix%2807.25.25%29.pdf.

[13]. Ash Johnson, “Restoring US Leadership on Digital Policy” (ITIF, July 2023), https://itif.org/publications/2023/07/31/restoring-us-leadership-on-digital-policy/.

[14]. Ash Johnson, “Europe Might Wrap the Tech Industry in Even More Red Tape” (ITIF, October 9, 2024), https://itif.org/publications/2024/10/09/europe-might-wrap-the-tech-industry-in-even-more-red-tape/.

[15]. “Fact Sheet: President Donald J. Trump Issues Directive to Prevent the Unfair Exploitation of American Innovation,” White House, February 21, 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/fact-sheets/2025/02/fact-sheet-president-donald-j-trump-issues-directive-to-prevent-the-unfair-exploitation-of-american-innovation/.

[16]. Daniel Michaels, Michael R. Gordon, and Kim Mackrael, “Trump Administration Targets Europe’s Digital Laws as a Threat to Basic Rights and U.S. Business,” The Wall Street Journal, May 15, 2025, https://www.wsj.com/politics/policy/trump-administration-targets-europes-digital-laws-as-a-threat-to-basic-rights-and-u-s-business-20db1016.

[17]. Zoe Kleinman, “‘I was moderating hundreds of horrific and traumatising videos,’” BBC, November 10, 2024, https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/crr9q2jz7y0o.

[18]. Spandana Singh, “Everything in Moderation: An Analysis of How Internet Platforms Are Using Artificial Intelligence to Moderate User-Generated Content,” New America, July 22, 2019, https://www.newamerica.org/oti/reports/everything-moderation-analysis-how-internet-platforms-are-using-artificial-intelligence-moderate-user-generated-content/.

[19]. “Commission releases Research API to facilitate the programmatic analysis of data in the Digital Services Act’s Transparency Database,” European Commission, February 19, 2025, https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/news/commission-releases-research-api-facilitate-programmatic-analysis-data-digital-services-acts.

[20]. Amaury Trujillo, Tiziano Fagni, and Stefano Cresci, “The DSA Transparency Database: Auditing Self-reported Moderation Actions by Social Media,” Proceedings of the 2025 ACM Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing 9, no. 2 (2025), https://arxiv.org/pdf/2312.10269.

[21]. Rishabh Kaushal et al., “Automated Transparency: A Legal and Empirical Analysis of the Digital Services Act Transparency Database,” Proceedings of the 2024 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (2024), https://facctconference.org/static/papers24/facct24-75.pdf.

[22]. Ibid.

Editors’ Recommendations

July 31, 2023

Restoring US Leadership on Digital Policy

October 9, 2024

Europe Might Wrap the Tech Industry in Even More Red Tape

January 13, 2020