How the Universal Service Fund Can Better Serve Consumers While Spending Less

Congress should reform and refocus the Universal Service Fund. It spends too much money, prioritizes the wrong problems, and funds it all with a high, sector-specific tax rate. Congress should reduce the overall size of the program and fund it with general revenue.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Key Takeaways

Contents

Introduction

The Universal Service Fund (USF), operated by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) in conjunction with the Universal Service Administrative Company (USAC), has grown old, expensive, and ineffective. It is past time for Congress to shrink, modernize, and retool it to address today’s broadband ecosystem. While the Supreme Court recently upheld the legal legitimacy of USF’s funding mechanism, the need to reform the program persists.[1]

The goal of many USF programs has been to close the deployment gap in America.[2] But thanks to ongoing investment from private Internet service providers (ISPs), the Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment (BEAD) program, and USF programs’ past success, the future of USF will be in a country that has achieved universal broadband deployment.[3]

Therefore, the first step toward reform should be distribution changes to focus funding on the remaining, and more pressing, causes of the digital divide, particularly broadband affordability. While programs such as E-Rate and Rural Healthcare need to be scrutinized to ensure that they are effective and targeted, this report focuses on the parts of USF that are most in need of reform: sunsetting the High-Cost program and reforming and augmenting the Lifeline program.[4]

Once policymakers have determined updated spending priorities, they should also turn to contribution reform to make USF sustainable without undue burdens on consumers.[5]

Distribution Reform

Effective distribution of USF funds should be consumer-focused and account for the broadband market as it exists today. The High-Cost program is out of step with that goal. Congress should move away from subsidizing ISPs’ operating expenditures (op-ex) and cut back on duplicative spending for deployment across government programs to eventually eliminate the High-Cost program. Future USF subsidies should focus on alleviating affordability issues that keep consumers from purchasing Internet service.

Broadband Deployment Success Calls for New Priorities

After BEAD and other federal broadband deployment programs succeed, the United States will have universal broadband deployment, or at least all the deployment subsidies can buy. Policymakers should make a fundamental decision not to subsidize op-ex for ISPs. If a company cannot effectively serve an area after receiving capital expenditure (cap-ex) subsidies to deploy a network, then serving that area is a profit opportunity for another company and not a justification for spending additional taxpayer dollars to prop up a failing provider. To be sure, broadband service in some areas will be unaffordable to consumers at market rates necessary to cover operating expenses, but that is an affordability problem USF should address via consumer-centric vouchers, not a reason to prop up uneconomical incumbents.

Federal Deployment Subsidies Are Numerous, Disjointed, and Obsolete

Across the federal government, there is poor coordination and there are duplicative programs focused on subsidizing broadband deployment, particularly ones that target rural areas. The Government Accountability Office (GAO) has released two reports on the issue over the last three years, and the overlapping missions of the BEAD program and USF’s High-Cost fund are a major part of the problem.[6]

The BEAD program provides $42.5 billion in funding to achieve high-speed broadband access throughout the United States, which is almost as much as was spent on broadband deployment by the entire federal government from 2009 to 2017.[7] BEAD’s one-time injection of capital will close the deployment gap in America, and yet, USF continues to spend the majority of its funds on a problem that, even before it was solved, only accounted for three percent of the digital divide in the United States.[8] The most recent GAO report highlights that the High-Cost program obligated $14.3 billion from 2021 to 2023 to address, ostensibly, the same problem that BEAD is going to resolve.[9]

Policymakers should make a fundamental decision not to subsidize op-ex for ISPs.

This overlap is just one example of a much larger problem. The first GAO report from 2023 finds that there were “more than 133 funding programs administered by 15 agencies,” of which 25 were mainly focused on broadband, and 13 on broadband deployment specifically.[10] In addition to BEAD and High-Cost, the list of duplicative deployment programs includes the Department of Agriculture’s ReConnect and Telecommunications Infrastructure programs and the National Telecommunications and Information Administration’s (NTIA’s) Broadband Infrastructure Program. Any overlapping spending on deployment is a mismanagement of government subsidies that Congress should address. In the USF context, a logical and impactful place to start would be by eliminating the USF’s High-Cost program, but Congress should pair its USF reform efforts with the elimination of other federal broadband deployment subsidies.

Eliminate the High-Cost Program

High-Cost is USF’s most expensive program, having spent $4.5 billion dollars in 2024—more than half of USF’s total spending that year.[11] High-Cost is broken down into different funds that all focus on broadband deployment to various regions and demographics.[12] Here, the programs that make up the High-Cost fund are grouped into three categories: 1) programs with committed funds that should be completed and then sunset (either because they are close to completion or would present undue complications in unwinding committed funds), 2) obsolete cap-ex subsidies that should be eliminated immediately, and 3) poor-policy op-ex subsidies that should also be eliminated immediately.

1. Programs to Sunset After Completion

▪ Connect USVI/Puerto Rico Fund ($950 million total, $50 million spent in 2024): This fund was created to restore, expand, and upgrade fixed and mobile communications infrastructure after Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands were devastated by hurricanes Irma and Maria in 2017. [13] The FCC allocated $950 million across a 10-year support period to ensure high-quality connectivity in Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. The support period will expire in 2029. Even though this fund does provide op-ex payments to carriers, the program is a one-time, disaster recovery and broadband expansion effort and should be completed and sunset at the end of the support period.

▪ Connect America Fund Phase II Auction (CAF II Auction) ($1.5 billion total, $148 million spent in 2024): The CAF II Auction is a blend of cap-ex and op-ex.[14] Given that deployment for this program will be complete this year, it is worthwhile to let the program run its course and then sunset when funding is fully obligated by 2029.

▪ Rural Digital Opportunity Fund (RDOF) ($20.4 billion total, $605 million spent in 2024): RDOF’s goal is to deploy networks and provide broadband and voice service to unserved homes and businesses in rural America.[15] The program began in 2020 with a support period of 10 years. Since it is halfway done and has already committed funding, RDOF should be completed and then sunset in 2030.

▪ Rural Broadband Experiments (RBE) ($100 million total, $1.6 million spent in 2024): The RBE fund provides subsidies from 2015 through 2025 to test the impact of deploying next-generation networks in rural areas of the United States. Given that the funding period of this relatively small program will end this year, it would be simplest to allow it to finish.

▪ Alaska Plan ($1.5 billion total, $129 million spent in 2024): The Alaska Plan was established in 2016 and provides op-ex funding to 23 carriers across a 10-year support period.[16] The program should be sunset after the support period ends in 2026.

2. Obsolete Cap-Ex Subsidies

▪ Enhanced Alternative Connect America Model (Enhanced ACAM) ($18 billion total, $1.3 billion spent in 2024, program runs through 2038): Enhanced ACAM was established to subsidize carriers that were already receiving CAF funding and willing to meet higher speed thresholds along with other stricter requirements. This large, long-term program is likely set to spend more than necessary to accomplish its goals. Indeed, many locations slated to get service via Enhanced ACAM may have become served by other means in the meantime. While the program already has obligated funds, the purpose of those funds is to connect households, not funnel money to ISPs for a problem that’s already been solved. Therefore, Congress and the FCC should evaluate the status of broadband available in Enhanced ACAM areas and recalibrate the program to serve only remaining gaps in an economically, cost-capped way. As the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) has argued for other subsidies, a cap of $1,200 per location served is a reasonable limit, given the development and availability of low-Earth orbit (LEO) satellite technology.

Congress and the FCC should craft the best language to rescind as much of this program as possible while managing litigation risk. It should be prepared to settle with or buy out Enhanced ACAM awardees rather than lock up over $18 billion until 2038; policymakers should cut their losses and reprioritize those funds where they would make a bigger dent in the digital divide.

3. Poor-Policy Op-Ex Subsidies

▪ Frozen High-Cost Support ($365 million spent in 2024): This program began in 2012 and was established to support the transition from telecommunications infrastructure to broadband infrastructure deployment in sparsely populated areas that have less return on investment.[17] Federal programs such as BEAD and private investment in network upgrades have rendered the need for subsidies such as this program obsolete, as next-generation networks are already being deployed.

▪ High-Cost Loop ($219 million spent in 2024): This program was established in 2012 and aims to help carriers maintain and improve services in high-cost areas.[18] Rather than continue to prop up carriers that would not survive in a normal marketplace, carriers should charge prices required to remain operational, and USF should focus on addressing costs for consumers who cannot afford the market price.

▪ Connect America Fund Broadband Loop Support (CAF BLS) ($994 million spent in 2024): CAF BLS has a deployment component, but mainly it provides funding to carriers to help recover costs of providing voice and broadband service.[19] The fund was established to replace an older op-ex fund and has since been made obsolete by the Enhanced ACAM program, which was designed to replace several CAF programs, including CAF BLS.

▪ Intercarrier Compensation Recovery (ICC Recovery) ($346 million spent in 2024): ICC Recovery is a component of CAF that supports changes to the intercarrier compensation system, which is the system of payments among carriers for phone calls that cross networks.[20] Like the other High-Cost op-ex programs, continuing to provide funding for carriers that would otherwise not be able to sustain themselves is poor policy that interferes with the normal functionality of the market. USF subsidies should be narrowly focused on the needs of consumers and should not continue to dole out funding to carriers simply because that is the status quo.

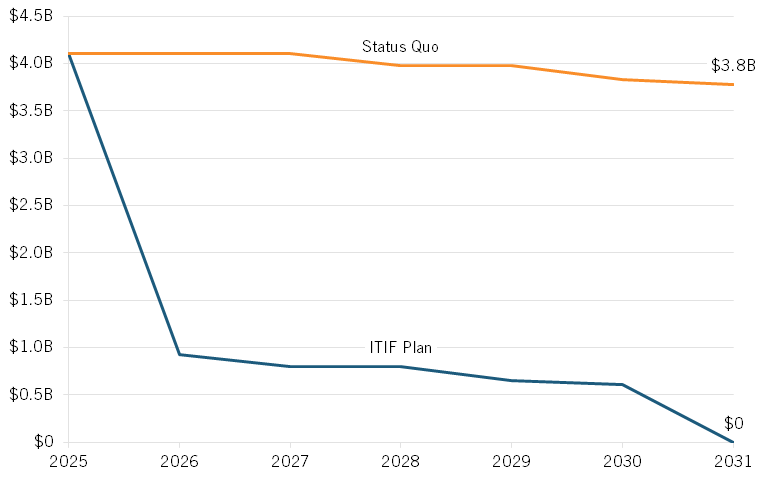

This plan for eliminating the High-Cost fund over the next five years would save a total of $20.9 billion in spending. Figure 1 and table 1 show the annual and total differences in spending for the ITIF plan versus the status quo for 2025 to 2031, if Congress and the FCC enacted these proposed reforms. The data is based on the full-year obligation amounts for 2024.[21]

Figure 1: ITIF plan vs. status quo spending on the High-Cost fund

Table 1: Annual reduction in High-Cost fund spending in ITIF’s plan vs. status quo

|

Status Quo |

ITIF’s Plan |

|||||||

|

Program |

2025 |

2026 |

2027 |

2028 |

2029 |

2030 |

2031 |

Total Reduction |

|

PR/USVI |

$50M |

$50M |

$50M |

$50M |

$50M |

$0 |

$0 |

$101M |

|

CAF II Auction |

$148M |

$148M |

$148M |

$148M |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$444M |

|

RDOF |

$605M |

$605M |

$605M |

$605M |

$605M |

$605M |

$0 |

$605M |

|

RBE |

$2M |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$9M |

|

AK Plan |

$129M |

$129M |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$643M |

|

ACAM |

$1.3B |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$7.5B |

|

FHCS |

$365M |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$2.2B |

|

HCL |

$219M |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$1.3B |

|

CAF BLS |

$994M |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$6.0B |

|

ICC |

$346M |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$2.1B |

|

Annual Spending |

$4.1B |

$932M |

$803M |

$803M |

$656M |

$605M |

$0 |

$20.9B |

|

Total Reduction |

$0 |

$3.2B |

$3.3B |

$3.3B |

$3.5B |

$3.5B |

$4.1B |

$20.9B |

The 5G Fund

The FCC’s 5G Fund is unique among the other High-Cost programs because of its scope and status.[22] The fund is designed to replace the Mobility Fund and was adopted by the FCC in 2020, with the auction to select providers set to take place in 2022. However, the program stalled and in 2024 Chairman Brendan Carr, a commissioner at the time, dissented on the vote for the program’s second report and order.[23] As of today, the program is still in limbo.

The FCC should not move forward with the 5G Fund until several necessary prerequisites are completed. First, the BEAD program should finish its deployment projects to ensure that the 5G Fund is not duplicative in the way most other High-Cost programs are. Second, subsidies for wireless infrastructure deployment should focus on areas that have no wireless options. Ensuring that every American has a mobile connection is critical for access to emergency services, but funding deployment in areas that already have mobile broadband would be wasteful. Finally, additional subsidies for mobile buildout must be preceded by universal copper line retirement.[24] With mobile access deployed across the country, there is no longer any need for legacy telephone networks.

A New and Improved Distribution Model: Modernized Lifeline Should Be the Flagship

With deployment complete, affordability and adoption are the two most substantial causes of the digital divide. Within USF, the Lifeline program could be reformed to effectively make broadband affordable for American consumers.[25] The program is already designed to provide affordability assistance to qualifying customers. Congress and the FCC should adjust Lifeline to be more targeted, flexible, and consumer focused. This change would make substantial headway toward achieving universal affordability.

ITIF previously proposed a broadband affordability plan that features a $30 per month voucher program for households that either have an income at or below 135 percent of the federal poverty line (already a feature of the Lifeline program) or are within the first three months of receiving unemployment insurance.[26] Recipients should be allowed to spend their $30 voucher on any broadband service of their choosing, without regard to technology or specific service plan details. The estimated annual cost of the ITIF plan is $3.4 billion, compared with the combined $5.4 billion price tag of High-Cost and Lifeline in 2024.[27]

A $30 per month voucher would make a $75 per month broadband subscription fall within the commonly used benchmark of 2 percent of income affordability for a two-person household at 135 percent of the federal poverty level.[28] While $30 is higher than the current support amounts provided to carriers via Lifeline, this new program would be implemented in tandem with the elimination of the High-Cost fund, meaning low-income households could get these benefits even while overall USF funding could shrink.[29]

In this way, a modernized Lifeline would also continue to support broadband buildout in a better way than High-Cost op-ex support can. Most private ISP deployments recoup their op-ex through monthly user fees. In high-cost areas, that monthly fee must be higher to recoup the higher operating costs. Helping low-income consumers afford that market-price service through Lifeline would thus preserve the investment incentives and competitive pressure in the ISP market by tying receipt of governments funds to provision of a service consumers value.

Low-income households could get these modernized Lifeline benefits even while overall USF funding could shrink.

Plus, a flexible, technology neutral approach for how the voucher is spent is critical to the reformed program’s success and reflects technological convergence in today’s broadband market.[30] With multiple technologies now providing high-speed Internet service to customers, allowing Lifeline recipients to choose whatever technology and plan works for them would make the program more concentrated on the specific needs of individual recipients.

Closing the digital divide should remain a priority for American broadband policy, but the causes of that divide have changed. The status quo disregards effective solutions for broadband affordability and continues to spend large sums on both broadband deployment and covering the operating expenses of unprofitable ISPs.[31] Shifting the priorities of USF spending from deployment to affordability is a necessary change for reforming the program so that it focuses on the connectivity challenges faced by American consumers today and in the future.

Contribution Reform

While the primary method of reducing the USF contribution factor should be to shrink the overall fund, reforming the contribution base for that smaller fund is still important. The current system is flawed in that it taxes “telecommunications services,” a sector-specific intermediate good, rather than being a neutral, broad-based tax. Many reform proposals seek simply to create more sector-specific taxes on more intermediate goods in a way that may forestall but will ultimately reproduce the deleterious effects of the current system. Instead, Congress should fund the aforementioned distribution priorities with general appropriations, or, failing that, some other system that approximates revenue drawn from all taxpayers.

Sector-Specific Fees Are No Free Lunch; Consumers Will Pay for USF

When deciding where to place the burden of a tax, such as the USF contribution factor, Congress must recognize that there is no free lunch to be had by legislating that businesses, rather than consumers, pay a tax. It is an economic fact that the incidence of a tax—that is, who really bears its burden—does not depend on who writes the check to the government. Indeed, the current contribution factor, while borne by consumers on their phone bills, is de jure on telecommunications companies.

A tax on a particular industry increases the cost of production for firms in that industry by the amount of the tax. Since the cost of production is the lowest price a producer will accept for any given good, an increase in production cost will result in higher prices for consumers. Faced with higher prices, some consumers will decide to no longer buy the taxed product; others will pay the higher price but get a smaller net benefit than they would without the tax.

While there can be reasonable debate about how to design a tax, Congress cannot legislate away the laws of economics. No clever mechanism exists to make only producers, and not consumers, bear some burden of a commodity tax.

Rather than chasing pots of gold at the end of any particular industry’s balance sheet, Congress should seek to keep the overall USF rate as low as possible.

A recent proposal suggests that the deadweight loss of sector-specific taxes is lower than that of drawing funding from general income tax revenues.[32] Reducing deadweight loss—the value of trades that don’t occur because of the tax—is an important consideration in crafting a tax plan. But taxing business inputs has hidden costs and inefficiencies that go beyond the lost transactions caused by the higher cost of the taxed good itself.[33] Inputs, such as advertising and cloud services, are intermediate steps in producing a final good. Therefore, an increase in their prices, caused by taxes, affects prices and business decisions at multiple other steps along the production process.

At whatever point a tax is placed, the next stage of production will have to account for it. The stage after that will, in turn, face the cost of the tax too. This expanding distortion, or tax pyramiding, produces inefficient outcomes beyond the specific transaction taxed.[34] Therefore, estimates of deadweight loss from a bespoke tax on an intermediate good likely underestimate its full cost.

Furthermore, sector-specific taxes would subject the program to the same kind of volatility that has caused the current predicament. The high USF contribution factor today is largely the result of the market shifting away from telecommunications services toward broadband services. Since the statute set a sector-specific fee mechanism, however, there is no way to cope with market shifts other than through ever higher rates. The same will be true for other sector-based contribution bases.

Digital ads, video streaming, cloud services, and artificial intelligence might seem like perpetual sources of revenue, but the future for any business model is uncertain, especially in dynamic and competitive technology markets. Some proposals explicitly target “big tech,” implying a size threshold for the companies whose customers would see the tax. Such a design only introduces unfairness alongside the distortions.[35]

Moreover, selecting only a few sectors as the contribution base would make USF subject to short-term economic downturns in those sectors. Even if a whole sector wouldn’t dry up for good, the contribution factor may have to change dramatically from quarter to quarter as business cycles shrink or grow revenues. This effect would inject uncertainty into the taxed markets, disincentivizing risk-taking and productivity-enhancing investments because they must hedge against the prospect of suddenly higher taxes.

These negative impacts of sector-specific USF fees would be dampened if the contribution factor had a much larger base.

A Better Way: “All Taxpayers” Is the Broadest Possible Base

Rather than chasing pots of gold at the end of any particular industry’s balance sheet, Congress should seek to keep the overall USF rate as low as possible.

Sector-specific proposals expand the base too little; because a broader base is best, Congress should tap the largest possible base: all taxpayers. Such a large base would result in an extremely low rate, estimated less than 0.1 percent to fund the current program, which Congress should substantially reduce, as described. This option would thus minimize economic distortions of USF fees without undue deadweight loss.

Given the entire tax base as USF contributors, legislative appropriations are the best funding mechanism for the remaining USF programs. Creating funding programs to achieve federal policy goals and then appropriating the money to pay for them is a standard government function. There is nothing special about USF programs that makes them unfit for appropriations.

There are, however, valid concerns that the appropriations process itself is beset by political uncertainty that will undermine the effectiveness of USF programs. Therefore, it is worthwhile to consider alternative funding structures than traditional annual appropriations.

One option would be to make a one-time appropriation after the fashion of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB).[36] The CFPB’s statute permits the agency to draw necessary funds from the Federal Reserve, thus appropriating funds while insulating that process from annual political battles. This type of expansive funding authority has already been blessed by the Supreme Court.[37] Congress could enable a similar mechanism for the FCC to fund USF from the same or a different funding source.

Another option would be to redesignate leftover BEAD funds to Lifeline. There are likely to be significant leftover BEAD funds now that NTIA’s updated guidance has reduced the total spending necessary to complete universal broadband deployment. The best use of these funds is for nondeployment activities that address the remaining causes of the digital divide, such as states establishing their own affordability and adoption programs within their own borders. But if Congress or NTIA will not let states keep the money they’ve saved from more economical deployment, a logical step would be for Congress to give the FCC authority to use leftover BEAD funds for the reformed Lifeline program previously described until High-Cost programs expire such that additional funding is not needed.

Under FCC v. Consumers’ Research, Congress Can Enable the FCC to Collect Contributions From All Taxpayers

In Consumers’ Research, the Supreme Court upheld USF’s contribution mechanism because the statute’s use of the term “sufficient” provided a “floor and ceiling” to the amount of money it raises—and the rest of Section 254 provides appropriate guidance about the nature and content of universal service.[38] Nothing in that holding depends on the identity of the contribution base. Indeed, the dissenting justices critiqued the majority for holding that even an expansive tax and spend system would be permissible.[39] But the majority opinion is binding. Congress can, therefore, expand the contribution base to sweep in not only certain industries but also all taxpayers. A statutory amendment to effect this change might look something like the following:

▪ Section 254(d) of the Communications Act of 1934 (47 U.S.C. § 254(d)) is amended as follows:

– Strike “telecommunications carrier that provides interstate telecommunications services” and insert “taxpayer”

– Strike “on an equitable and nondiscriminatory basis” and insert “from his gross income”

– Strike “The Commission may exempt a carrier” and all that follows.

▪ Add definitions:

– The term “taxpayer” has the meaning given to it by Section 7701(a)(14) of the Internal Revenue Code (26 U.S.C. § 7701).

– The term “income” has the meaning given to it by Section 61 of the Internal Revenue Code (26 U.S.C. § 61).

The FCC and USAC can work with the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) to implement this contribution mechanism efficiently, which should be less administratively burdensome for the FCC since the IRS already has access to data about taxpayers and their income. There would be no need to incur the administrative costs of assessing industry sectors’ revenue in a bespoke revenue scheme.

Ultimately, if Congress does not think that the societal benefits of USF are worth taxpayers in general paying for them, it should alter its distribution plan until they are worth it. A scheme of parochial taxes to fund parochial subsidies is bad for everyone except the rent seekers who get those subsidies.

Legislation Is Necessary to Alter the Contribution Base

FCC chairs from both parties agree that expanding the USF contribution base would require an act of Congress; the FCC does not have the authority to expand the base on its own. Chairwoman Rosenworcel informed Congress that imposing USF fees on business-to-business transactions would be a “significant undertaking and the Commission would require authority from Congress” as those transactions are “conducted by companies over which the Commission does not currently have authority” and “authorizing the Commission to assess edge providers for USF purposes” would “require congressional action.”[40] Chairman Carr proposed expanding the base, but when specifying what action is needed wrote, “Congress should enact legislation.”[41] In a post-Loper Bright world, the FCC has less discretion to claim authority over sectors that the statute as written does not directly encompass.[42] Since, therefore, legislation will be necessary for any base-widening endeavor, Congress should use the full breadth of its authority, as defined by the Supreme Court, to exact neutral contributions from the broadest possible base.

Conclusion

USF reform should be an urgent congressional priority. The program is spending too much money on programs with too little effect on the digital divide. A leaner USF that prioritizes broadband affordability and adoption, rather than ongoing op-ex subsidies, would better serve consumers and steward taxpayer funds.

About the Authors

Joe Kane is director of broadband and spectrum policy at ITIF. Previously, he was a technology policy fellow at the R Street Institute, where he covered spectrum policy, broadband deployment and regulation, competition, and consumer protection. Earlier, Kane was a graduate research fellow at the Mercatus Center, where he worked on Internet policy issues, telecom regulation, and the role of the FCC, where he interned in the office of Chairman Ajit Pai. He holds a J.D. from The Catholic University of America, a master’s in economics from George Mason University, and a bachelor’s in political science from Grove City College.

Ellis Scherer is a policy analyst at ITIF covering broadband and spectrum policy. He previously interned with NTIA and worked as a cybersecurity consultant. He holds a master’s degree in terrorism and homeland security policy from American University and a bachelor’s degree in politics and history from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

About ITIF

The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) is an independent 501(c)(3) nonprofit, nonpartisan research and educational institute that has been recognized repeatedly as the world’s leading think tank for science and technology policy. Its mission is to formulate, evaluate, and promote policy solutions that accelerate innovation and boost productivity to spur growth, opportunity, and progress. For more information, visit itif.org/about.

Endnotes

[1]. FCC v. Consumer’s Research, 606 U.S., (2025), https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/24pdf/24-354_0861.pdf.

[2]. “Universal Service” Universal Service Administrative Co. (USAC), accessed August 25, 2025, https://www.usac.org/about/universal-service/.

[3]. Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, H.R. 3684, Division F, Title 1, Section 60102(b), Broadband, Equity, Access, and Deployment Program, 117th Congress, https://www.congress.gov/117/plaws/publ58/PLAW-117publ58.pdf.

[4]. “E-Rate,” Universal Service Administrative Co., accessed August 25, 2025, https://www.usac.org/e-rate/; “Rural Health Care,” Universal Service Administrative Co., accessed August 25, https://www.usac.org/rural-health-care/; “High Cost,” Universal Service Administrative Co., accessed August 25, 2025, https://www.usac.org/high-cost/; “Lifeline,” Universal Service Administrative Co., accessed August 25, 2025, https://www.usac.org/lifeline/.

[5]. Joe Kane, “Sustain Affordable Connectivity By Ending Obsolete Broadband Programs” (ITIF, July 2023), https://itif.org/publications/2023/07/17/sustain-affordable-connectivity-by-ending-obsolete-broadband-programs/.

[6]. “A National Strategy Needed to Coordinate Fragmented, Overlapping Federal Programs,” GAO, May 2023, https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-23-106818.pdf; “Broadband Programs: Agencies Need to Further Improve Their Data Quality and Coordination Efforts,” April 2025), https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-25-107207.pdf.

[7]. “A National Strategy Needed to Coordinate Fragmented, Overlapping Federal Programs,” GAO, https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-23-106818.pdf;Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, H.R. 3684, Division F, Title 1, Section 60102(b), Broadband, Equity, Access, and Deployment Program, https://www.congress.gov/117/plaws/publ58/PLAW-117publ58.pdf.

[8]. Doug Brake and Alexandra Bruer, “How to Bridge the Rural Deployment Gap Once and For All” (ITIF, March 22, 2021), https://itif.org/publications/2021/03/22/how-bridge-rural-broadband-gap-once-and-all/; NTIA Data Explorer: Internet Use Survey Non-Use of the Internet at Home, updated November 2023, https://www.ntia.gov/data/explorer#sel=noNeedInterestMainReason&demo=&pc=prop&disp=chart.

[9]. “Broadband Programs: Agencies Need to Further Improve Their Data Quality and Coordination Efforts,” GAO, https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-25-107207.pdf.

[10]. “A National Strategy Needed to Coordinate Fragmented, Overlapping Federal Programs,” GAO.

[11]. “2024 Annual Report,” USAC, 2025, https://www.usac.org/wp-content/uploads/about/documents/annual-reports/2024/2024_USAC_Annual_Report.pdf.

[12]. “High Cost,” USAC, accessed August 27, 2025, https://www.usac.org/high-cost/.

[13]. “Bringing Puerto Rico (Uniendo a Puerto Rico) Fund and the Connect USVI Fund,” USAC, accessed August 27, 2025, https://www.usac.org/high-cost/funds/bringing-puerto-rico-together-uniendo-a-puerto-rico-fund-and-the-connect-usvi-fund/.

[14]. “CAF Phase II Auction,” USAC, accessed August 27, 2025, https://www.usac.org/high-cost/funds/caf-phase-ii-auction/.

[15]. “Rural Digital Opportunity Fund,” USAC, accessed August 27, 2025, https://www.usac.org/high-cost/funds/rural-digital-opportunity-fund/.

[16]. “Alaska Plan,” USAC, accessed August 27, 2025, https://www.usac.org/high-cost/funds/alaska-plan/.

[17]. “Frozen High Cost Support,” USAC, accessed August 27, 2025, https://www.usac.org/high-cost/funds/legacy-funds/frozen-high-cost-support/.

[18]. “High Cost Loop,” USAC, accessed August 27, 2025, https://www.usac.org/high-cost/funds/legacy-funds/high-cost-loop/.

[19]. “CAF Broadband Loop Support,” USAC, accessed August 27, 2025, https://www.usac.org/high-cost/funds/caf-broadband-loop-support/.

[20]. “ICC Recover,” USAC, accessed August 27, 2025, https://www.usac.org/high-cost/funds/legacy-funds/icc-recovery/.

[21]. “High Cost,” USAC.

[22]. “Mobility Fund Phase II (MB-II),” Federal Communications Commission (FCC), accessed August 27, 2025, https://www.fcc.gov/mobility-fund-phase-ii-mf-ii.

[23]. Brendan Carr, “DISSENTING STATEMENT OF COMMISSIONER BRENDAN CARR, Re: Establishing a 5G Fund for Rural America,” FCC, August 2024, https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/FCC-24-89A3.pdf.

[24]. Ellis Scherer, “California Should Modernize Its Carrier-of-Last-Resort Challenge” (ITIF, June 2025), https://itif.org/publications/2025/06/23/california-should-modernize-its-carrier-of-last-resort-requirements/.

[25]. “Lifeline,” USAC, accessed August 27, 2025, https://www.usac.org/lifeline/.

[26]. Joe Kane, “A Blueprint for Broadband Affordability” (ITIF, January 2025), https://itif.org/publications/2025/01/13/a-blueprint-for-broadband-affordability/.

[27]. Kane, “A Blueprint for Broadband Affordability”; “The Universal Service Fund and Related FCC Broadband Programs: Overview and Considerations for Congress,” CRS, July 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R47621.

[28]. Kane, “A Blueprint for Broadband Affordability.”

[29]. “Code of Federal Regulations: Subpart E—Universal Service Support for Low-Income Consumers,” National Archives, accessed August 19, 2025, https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-47/chapter-I/subchapter-B/part-54/subpart-E.

[30]. Ellis Scherer and Joe Kane, “Broadband Convergence Is Creating More Competition” (ITIF, July 2025), https://itif.org/publications/2025/07/07/broadband-convergence-is-creating-more-competition/.

[31]. Kane, “A Blueprint for Broadband Affordability.”

[32]. James E. Prieger, “An analysis of options for reforming the Universal Service Fund funding mechanism” (Digital Progress, July 2025), https://digitalprogress.tech/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/USF-funding-reform-Prieger.pdf.

[33]. Jared Walczak, “Modernizing State Sales Taxes: A Policymakers Guide” (Tax Foundation, September 2024), https://taxfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/FF845.pdf; Jared Walczak, “Worse Than Advertised: The Legal and Economic Pitfalls of Maryland’s Digital Advertising Tax” (Tax Foundation, March 2020), https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/state/maryland-digital-advertising-tax/.

[34]. Ibid.

[35]. Joel Thayer and Roslyn Layton, “The Court Did Its Job, Now It’s Time for Congress to Get Millions of Americans Online,” Broadband Breakfast, August 22, 2025, https://broadbandbreakfast.com/the-court-did-its-job-now-its-time-for-congress-to-get-millions-of-americans-online/.

[36]. “Consumer Financial Protection Bureau,” USA.gov, accessed August 28, 2025, https://www.usa.gov/agencies/consumer-financial-protection-bureau.

[37]. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau v. Community Financial Services Association of America, Limited, 601 U.S. 416 (2024), https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/23pdf/22-448_o7jp.pdf.

[38]. FCC v. Consumer’s Research, 606.

[39]. Ibid, 34.

[40]. Jessica Rosenworcel, “Letter to Senator Ben Ray Lujan,” FCC, January 2024, https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/DOC-400113A1.pdf.

[41]. Brendan Carr, “Ending Big Tech’s Free Ride,” Newsweek, May 24, 2021, https://www.newsweek.com/ending-big-techs-free-ride-opinion-1593696.

[42]. Loper Bright v. Raimondo, 603 U.S. (2024), https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/23pdf/22-451_7m58.pdf.

Editors’ Recommendations

March 22, 2021

How to Bridge the Rural Broadband Gap Once and For All

January 13, 2025

A Blueprint for Broadband Affordability

February 17, 2022

Comments to the FCC on the Future of the Universal Service Fund

Related

September 15, 2025