Comments to the FCC Regarding Modernizing Spectrum Sharing for Satellite Broadband

The Commission’s Methodology Should Seek to Maximize the Productivity of Satellite Spectrum. 1

The Satellite Broadband Ecosystem Is Vastly Different From 25 Years Ago. 2

The Commission Should Adopt the Degraded Throughput Threshold From the NGSO-NGSO Sharing Framework 3

Introduction and Summary

The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation appreciates the opportunity to comment on the review of the spectrum sharing regime between geostationary (GSO) and non-geostationary (NGSO) satellites in the 10.7–12.7, 17.3–18.6, and 19.7–20.2 GHz bands.[1] The Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (“NPRM”) investigates ways to improve satellite spectrum sharing to get the most productive use of the spectrum and ensure continued growth and innovation in the U.S. space economy. To achieve these goals, the Commission should apply the degraded throughput methodology from the NGSO-NGSO sharing rules to create a more effective alternative to the existing rules based on equivalent power-flux density (EPFD) limits.

The Commission’s Methodology Should Seek to Maximize the Productivity of Satellite Spectrum

The goal of spectrum policy should be to maximize the productivity of spectrum. Efficient management of interference is key to that goal, but the optimal level of interference is not zero.[2] The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) should seek to facilitate productive use of the spectrum, which entails not leaving capacity on the table.

EPFD limits are rules set by the International Telecommunications Union (ITU) and adopted by the FCC that aim to ensure effective spectrum sharing by preventing harmful interference between satellites.[3] However, the rules are based on an outdated understanding of the NGSO-GSO satellite ecosystem, resulting in over-restrictive sharing rules that reduce the productivity of satellite spectrum and, in particular, prevent consumers from realizing the full potential of NGSO broadband service. NGSOs could be operating in ways that would violate EPFD limits but would not cause harmful interference to GSO satellites.

The extreme restrictiveness of the current EPFD produces absurd results. For example, EPFD limits must be adhered to even for areas where there is no GSO earth station.[4] This approach unnecessarily limits the ability of satellites to increase capacity in areas where fewer restrictions would not lead to harmful interference. EPFD limits for NGSOs relative to GSOs are also far more restrictive than what is required for GSOs sharing with each other.[5] These are some indications that the current rules unnecessarily inhibit the productivity of shared NGSO-GSO satellite spectrum.

The Satellite Broadband Ecosystem Is Vastly Different From 25 Years Ago

While GSO operations used to dominate the space economy, the rapid growth of NGSO constellations necessitates revisiting the rules from the GSO-only days to ensure they are not holding back the next generation of the space economy.

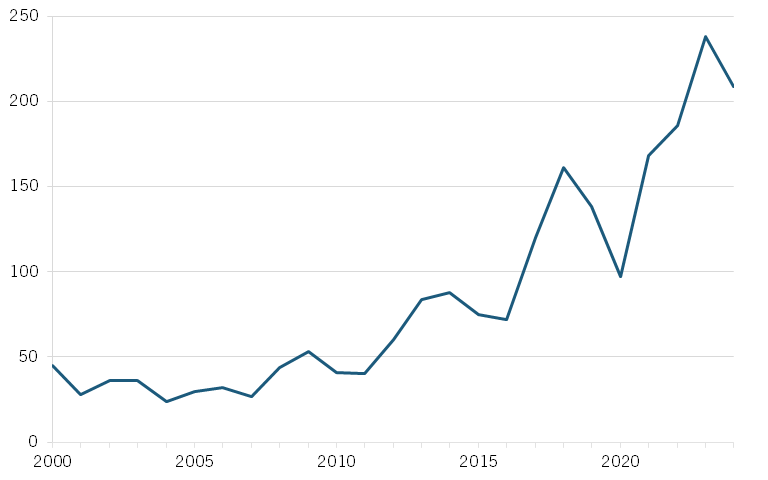

The satellite economy is unrecognizable today compared to when EPFD limits were set a quarter-century ago. There has been a steady increase in entrants, with four times the number of different owners and operators in today’s global satellite marketplace than in 2000.[6] The growth in the number of providers has stressed the old system and revealed the need for more effective spectrum sharing methods.

Figure 1: Number of owners and operators launching satellites globally per year, 2000–2024[7]

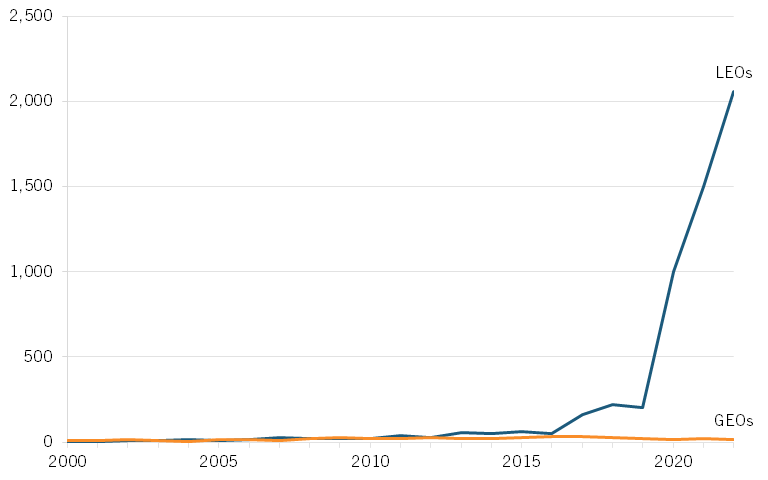

Within the U.S. satellite economy specifically, the number of NGSO satellites launched annually has dramatically increased.[8] The current largest constellation of NGSO satellites, owned by SpaceX, has nearly 8,000 operational satellites in orbit—thousands more than there were just five years ago, let alone a quarter-century ago.[9]

Figure 2: Number of GEO and LEO satellites launched from the United States annually, 2000–2022[10]

These statistics are indicative of the immense growth of the satellite industry since the ITU first introduced EPFD limits. This growth necessitates an updated framework for satellite spectrum sharing that reflects the satellite market as it exists today. EPFD limits are a blunt instrument calibrated to prevent any possibility of any interference with timeworn incumbents, not maximize productivity.

The Commission Should Adopt the Degraded Throughput Threshold From the NGSO-NGSO Sharing Framework

The Commission should replace EPFD limits with the degraded throughput methodology that is used for NGSO-NGSO spectrum sharing and for NGSO-GSO sharing in the V-band.[11] This change would increase the productivity of shared satellite spectrum as compared to what can be achieved through using EPFD limits.

The Commission’s adoption of a degraded throughput methodology in the bands under consideration would acknowledge the fact that sometimes the cost of mitigating all interference makes the spectrum far less usable. Using a degraded-throughput regime in these bands will protect the existing rights of GSO operations while allowing NGSOs to increase their capacity and avoid needless constraints on future entrants to the market. Degraded throughput accounts for the dynamic design and operational capabilities of NGSO satellites, while the rigid design of EPFD limits does not.[12]

Conclusion

Satellite service has already become a critical part of the U.S. broadband ecosystem. Satellite broadband has proven indispensable for serving the most rural and low-income parts of the country, providing life-saving connectivity during natural disasters and emergencies, and will play an increasingly important role in national security. The Commission should facilitate necessary improvements to existing spectrum sharing frameworks that focus on setting a workable backdrop for coordination and negotiation that promotes the productive use of satellite spectrum. Thank you for your consideration.

Endnotes

[1]. Founded in 2006, ITIF is an independent 501(c)(3) nonprofit, nonpartisan research and educational institute—a think tank. Its mission is to formulate, evaluate, and promote policy solutions that accelerate innovation and boost productivity to spur growth, opportunity, and progress. ITIF’s goal is to provide policymakers around the world with high-quality information, analysis, and recommendations they can trust. To that end, ITIF adheres to a high standard of research integrity with an internal code of ethics grounded in analytical rigor, policy pragmatism, and independence from external direction or bias. For more, see: “About ITIF: A Champion for Innovation,” https://itif.org/about; “Modernizing Spectrum Sharing for Satellite Broadband,” Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (SB Docket No. 25-157, July 28, 2025) https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/FCC-25-23A1.pdf (NPRM).

[2]. See, Ronald Coase, “The Federal Communications Commission,” The J. of L. and Econ., Oct. 1959, 27. “It is sometimes implied that the aim of regulation in the radio industry is to minimize interference. But this would be wrong. The aim should be to maximize output.”

[3]. See, International Telecommunications Union, “Radio Regulations,” Chapter V, Article 22, Section 22.5D, 2000, https://life.itu.int/radioclub/rr/art22.pdf.

[4]. Ibid.

[5]. NPRM, para. 12.

[6]. “Satellite statistics: Number of organizations,” Jonathan’s Space Pages, accessed July 16, 2025, https://www.planet4589.org/space/stats/out/nowner.txt.

[7]. Ibid.

[8]. “UCS Satellite Database,” Union of Concerned Scientists, accessed July 17, 2025, https://www.ucs.org/media/11491.

[9]. “Starlink Statistics,” Jonathan’s Space pages, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.planet4589.org/space/con/star/stats.html.

[10]. “UCS Satellite Database,” Union of Concerned Scientists, accessed July 17, 2025, https://www.ucs.org/media/11491.

[11]. See “Revising Spectrum Sharing Rules for Non-Geostationary Orbit, Fixed-Satellite Service,” Second Report and Order and Order on Reconsideration (IB Docket No. 21-456, November 4, 2024), para. 11, https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/FCC-24-117A1.pdf and International Telecommunications Union, “Radio Regulations,” Chapter V, Article 22, Section 22.5D, 2000, https://life.itu.int/radioclub/rr/art22.pdf.

[12]. See Kuiper Comments in IB Docket No. 21-456 and RM-11855, 7, https://www.fcc.gov/ecfs/document/1032530465068/1.