Mission-Oriented Innovation or Mission-Enabled Innovation?

Like any field, innovation policy is not immune to fads. Fads are a convenient substitute for the hard work of critical thinking applied to specific times and places, which is why they spread. The latest is “mission-oriented innovation” (MOI). The idea is that the central organizing principle for government innovation policy should be to invent missions tied to societal challenges in order to justify public innovation efforts and interventions.

If there’s an international guru of MOI, it’s Mariana Mazzucato, a UK economist who proudly describes herself as “one of the world’s most influential economists... on a mission to save capitalism from itself.” Perhaps the most enthusiastic disciple of Mazzucatonomics is the European Union—an institution perennially in search of purpose. And in Mazzucatonomics, it seems to have found one.

The EU has plunged headfirst into the MOI pool, launching new innovation programs around missions such as curing cancer, restoring soil health, reviving oceans, and, of course, saving the planet from climate change.

It would be one thing if the EU were the only place drinking the MOI Kool-Aid. Europe is already lagging far behind in innovation, in part due to its rigid adherence to the precautionary principle in regulation, so we can’t expect much from Brussels in terms of boosting global technological progress.

But MOI is catching on elsewhere, too. Think tanks, scholars, advocates, and policymakers across Canada, Korea, Japan, the UK, and even the United States are getting on board. The Biden administration’s “cancer moonshot” and climate change initiatives are clear nods to the MOI playbook.

So what’s the problem?

Nothing—if you believe that growing the economy and ensuring Western nations stay ahead of China in the advanced technology race are irrelevant or even harmful. But if you care about either of those things, there’s plenty to worry about.

The core issue is that MOI diverts innovation policy from its historical focus on economic growth and global competitiveness, reorienting it toward broad social concerns. That might be fine if a democratic society decides that cleaning up the oceans is its top priority. But the MOI advocates don’t sell their formula as a tradeoff.

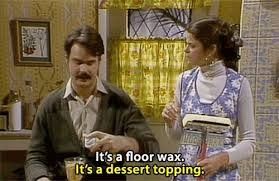

Instead, they promise, in the words of Dan Aykroyd and Gilda Radner’s classic SNL skit, that MOI is both a floor wax and a dessert topping. Stated differently, MOI will simultaneously solve pressing social problems and supercharge your nation’s lagging innovation and tech competitiveness.

Really?

What’s more likely to boost EU growth and competitiveness in the global tech race: a targeted innovation strategy for AI and robotics or one focused on cleaner oceans? Healthier soil or a revitalized European auto industry? Just asking.

Mazzucato has cleverly deployed a sleight-of-hand trick: hijack innovation policy in service of left-wing social goals, which have always been the ultimate aim. Much of the political left now explicitly rejects growth-oriented capitalism (which Mazzucato, thankfully, aims to rescue us from) and instead champions a vision of society that looks more like Hobbiton—idyllic, deindustrialized, and with perfect income equality.

The goal is to redirect industrial and innovation policy away from productivity and competitiveness and toward a utopian, post-growth vision.

In this way, Mazzucato is a 21st-century heir to 19th-century rural socialists like Robert Owen, Charles Fourier, and Henri de Saint-Simon. But instead of communal farms, her motor to achieving this new utopia is government-led innovation policy. Personally, I’d be delighted to live in Hobbiton—so long as my income doesn’t shrink and I still have access to today’s technology. Who wouldn’t? But that’s not the agenda the MOI degrowth advocates have in mind.

So what should policymakers do when confronted with a proposed innovation “mission”? They should ask themselves three questions:

- Is this particular problem worth devoting scarce public resources to solve, given real tradeoffs and other national priorities? Just because a challenge tugs at the heartstrings doesn’t mean it merits billions in R&D spending, especially if it crowds out more growth-relevant investments.

- Is innovation policy the best tool for addressing the problem or achieving the goal? Sometimes it might be. Sometimes regulation or direct public investment, like building infrastructure, might be more effective.

- Will the proposed innovation mission actually generate the economic benefits its proponents claim, such as higher wages, stronger productivity, or more competitive domestic firms? MOI pitchmen routinely sell their ideas on these grounds—because they know that voters aren’t exactly clamoring for a communist Hobbiton. But the evidence backing their economic claims is often thin or nonexistent.

This is not to say there are no good missions. Some can offer dual-use benefits, like addressing social problems while also advancing productivity and competitiveness. That’s the sweet spot policymakers should look for.

One promising example: housing construction innovation. Many advanced nations face a housing affordability crisis. Innovation in construction could play a meaningful role, especially by advancing emerging technologies such as building information modeling (BIM), 3D printing, robotic assembly, and new materials. For countries that implement a construction innovation mission, there’s potential to lower housing costs and cultivate internationally competitive firms in these technologies and related industries.

That’s mission-enabled innovation—where a real-world mission unlocks growth-oriented innovation, not the other way around.

Ultimately, the most important question policymakers must ask is: What problem(s) do we want innovation policy to solve? If the answer is “faster growth in living standards, a stronger industrial base, and sustained global competitiveness,” then tread carefully with MOI. It’s an appealing vision, but one that may deliver neither the economic gains nor the social progress its champions promise.