Europe’s Innovation Lethargy Should Be a Lesson of What Not to Do, Even for a Leading US

Europe was once the epicenter of global innovation, giving birth to the Industrial Revolution and shaping the trajectory of the modern economy. However, over the last few decades, it has lost its edge. In the global race for technological leadership, the United States and China have seized the lead in many emerging technologies, including artificial intelligence (AI) and advanced computing. While the reasons are multifaceted, Europe’s ambiguity toward new technology—and its embrace of the precautionary principle—plays a key role.

Despite being home to some of the world’s best engineers, universities, and research institutions, Europe has failed to retain top talent and technology companies compared to the United States and China. For instance, DeepMind, one of the world’s earliest AI labs, was founded in the United Kingdom in 2010. However, it was acquired by Google in 2014 after struggling to secure funding from more risk-averse European venture capitalists. Today, DeepMind underpins Google’s AI leadership and stands alongside the sector’s American frontrunners, including OpenAI, Anthropic, and xAI.

Similarly, China is emerging as a formidable AI powerhouse, with platforms such as DeepSeek and Alibaba’s Qwen models performing on par with their American counterparts. Although promising European AI companies exist, such as France’s Mistral and Hugging Face, they remain few and suffer from a lack of venture funding compared to their American rivals.

Europe’s preference for secure, low-risk investments over bold bets on disruptive innovation has led to a shallower venture capital market. More risk-tolerant investors in the United States are pouring billions into AI development, while Europe has yet to produce a single trillion-dollar tech company. In fact, all seven of the world’s trillion-dollar tech firms are American, but Europe can claim only 28 businesses with valuations over $100 billion.

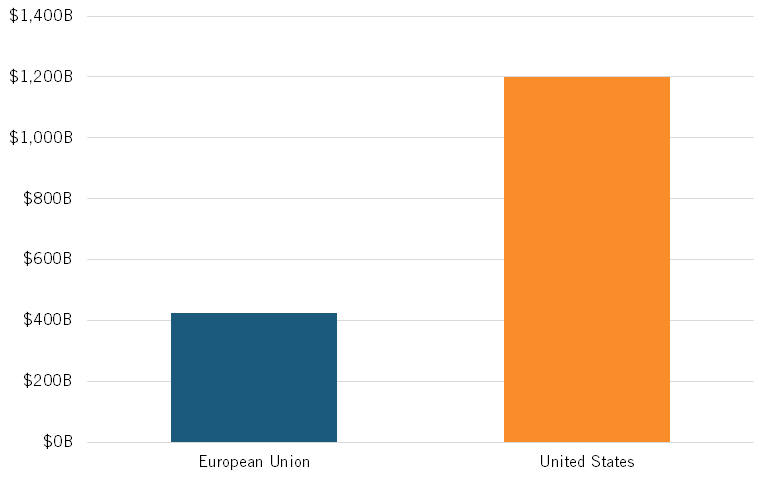

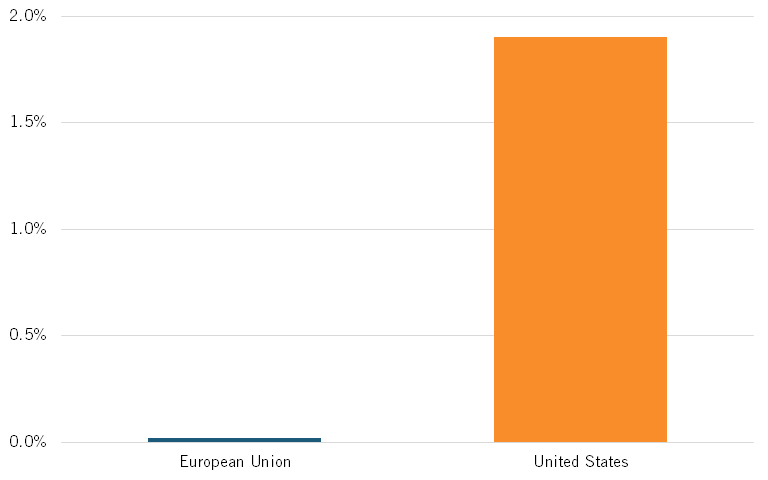

According to the 2024 State of European Tech report, European firms raised $426 billion over the past decade, roughly $800 billion less than U.S. firms during the same period. (See figure 1.) In China, government guidance funds have successfully facilitated public-private partnerships in venture capital-like investments, raising $700 billion as of 2021. Meanwhile, European pension funds, which manage around $9 trillion in assets, allocate just 0.018 percent to venture capital—more than 100 times less than the 1.9 percent invested by American pension funds. (See figure 2.) This lack of early-stage investment has impeded Europe’s ability to scale its start-ups into global competitors.

Figure 1: Private technology funding for Europe and the United States in the last decade

Figure 2: Pension fund allocation towards venture capital

Europe’s R&D spending is also lagging. According to the National Science Foundation’s National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, the United States invested nearly $900 billion—equivalent to 3.59 percent of GDP—into research and development in 2022. That same year, China, where development costs are significantly lower, allocated $450 billion (2.56 percent of GDP) toward R&D. The EU, by contrast, invested just over $400 billion in 2023, or 2.22 percent of GDP, according to Eurostat—roughly half the U.S. investment in both relative and absolute terms. While nominally similar to China’s total, Europe’s higher research costs diminish the impact of its spending. This chronic underinvestment has left Europe struggling to keep pace in high-tech industries and has weakened its ability to foster homegrown innovation.

Simultaneously, an adversarial relationship has emerged between the European Union government and the tech sector. While stringent regulations—such as the Digital Market Act, Digital Services Act, Artificial Intelligence Act, Cyber Resilience Act, and General Data Protection Regulation—are aimed at protecting consumers and European businesses, they prioritize control and oversight at the expense of flexibility. The result is a significant compliance burden that can stifle innovation. The AI Act, adopted in 2024, is the world’s first major legal framework for artificial intelligence. It classifies AI systems by risk level and imposes strict requirements on those deemed high-risk, including facial recognition and health technologies. For small start-ups, such onerous rules can be nearly impossible to navigate, deterring novel technologies from even getting off the ground and pushing cutting-edge R&D outside the EU.

By contrast, the United States and China offer far more supportive environments for innovation. U.S. initiatives, such as the CHIPS and Science Act and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act—and Chinese programs like Made in China 2025 and the Torch Program—are fueling progress by collectively allocating trillions toward emerging technologies. In China, designated “green zones” promote start-up growth by drastically reducing bureaucratic barriers, offering tax incentives and subsidized office space, and providing streamlined access to state-backed venture capital. These zones serve as high-tech incubators, standing in stark contrast to the fragmented, regulation-heavy environment that European start-ups face. Additionally, the EU’s patchwork of 27 different national regulatory systems creates a maze of complex legal, tax, and financial reporting requirements, hindering scalability and cross-border investment.

The results for Europe have been troubling. Since 2008, EU GDP has grown only marginally—from $16.4 trillion to $18.6 trillion in 2023, according to the World Bank. Over the same period, U.S. GDP nearly doubled, from $14.9 trillion to $27.9 trillion, while China’s GDP ballooned from $4.6 trillion to $17.8 trillion.

Europe’s innovation drag should serve as a stark warning. While the Draghi Report was a wake-up call for European policymakers, it’s unclear whether it was loud enough to disrupt them from their slumber.

It should also serve as a cautionary lesson for the United States that technological leadership is a position that must be actively defended. While the U.S. currently enjoys a strong innovation ecosystem, China is rapidly closing the gap with a coherent industrial policy and massive state support. To remain competitive and safeguard the slowing innovation pipeline, the federal government must continue investing in long-term science R&D, supporting robust public-private partnerships, and fostering dynamic start-up ecosystems by expanding programs like the CHIPS and Science Act while reducing barriers for emerging tech companies.

The United States should also avoid looking eastward to Europe for regulatory inspiration. It must remain vigilant about the consequences of regulatory overreach and legal fragmentation—especially as states begin to chart independent paths on AI, data privacy, and digital markets. For example, the California Privacy Rights Act imposes stricter data protection standards than other states. At the same time, New York’s Algorithmic Accountability Act and Illinois’ Biometric Information Privacy Act differ significantly from the more limited federal guidelines. Though these laws aim to address legitimate concerns, they risk creating a compliance minefield that could undermine entrepreneurship and innovation. That’s why Congress should maintain the ten-year moratorium on state-level AI regulation. And, as ITIF has written, Congress should enact much broader federal preemption of state digital rules that undercut interstate digital commerce.

American policymakers must likewise resist the urge to constrain the tech sector under the guise of consumer protection or antitrust. Doing so risks burdening firms and pushing talent and investment overseas. A cohesive national strategy is vital to sustaining an innovative economy. The EU’s decline illustrates how overregulation and fragmented markets can stifle innovation.

Protecting America’s position at the forefront of technological progress will require sustained investment, coordinated national policy, and a willingness to prioritize long-term technological strength over short-term political gain. Without this focus, the United States risks ceding its competitive edge to a more strategically aligned global rival.

Related

October 16, 2025