Broadband Convergence Is Creating More Competition

Multiple broadband technologies are delivering high-speed Internet service to consumers, creating even more robust competition. Yet, regulations are misaligned with market realities and should be updated to help maximize the consumer benefits of this increasing competition.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Key Takeaways

Contents

Convergence: Advances In Substituable Broadband Technologies 3

More Substitutes Have Led To More Competition. 6

Policies Are Out of Step With Today’s Competitive Marketplace 10

Mergers Could Benefit Broadband Consumers 13

Introduction

The U.S. broadband market is experiencing even stronger competition than in years past, driven in large part by technological convergence and new players entering the home broadband market. Where once home broadband service was only available from incumbent cable or telephone companies, new technologies have entered the fray, and incumbents themselves have had to reconceptualize their networks around broadband rather than specialized video or voice service.

Today, there are four broad categories of home broadband technology that deliver substitutable performance for most consumer applications: fiber optic networks (referred to here as fiber), coaxial cable (cable), fixed wireless access (FWA), and low-earth-orbit (LEO) satellite constellations. This convergence increases the competitive dynamics that were already present but limited by the footprint of incumbent telephone and cable companies. These new avenues of competition benefit consumers.

There are numerous indicators of strong competition in today’s broadband market, including normal industry profit margins, active promotional activities, diverse consumer choice patterns, and competitive pricing dynamics, that together demonstrate that there is genuine competitive pressure across the entire market, regardless of the technology used to provide service. Moreover, the rise of new broadband technologies is in itself evidence of healthy competition.

In this competitive environment, many regulatory frameworks are outdated, and some policy proposals are out of step with the new market realities. Rate regulation initiatives, obsolete universal service mechanisms, calls for Title II utility-style oversight, and government-owned network deployments reflect policy approaches more appropriate for legacy monopoly industries, not today's multiplatform environment. Spectrum policies that lack flexibility or tie up valuable bandwidth in inefficient federal holdings are increasingly harmful to consumers. It is time for policy frameworks to adapt to recognize and bolster competitive outcomes rather than perpetuate interventions designed for past segmented markets which have now converged.

Convergence: Advances In Substituable Broadband Technologies

For years, high-speed home broadband Internet access has been the principal province of wireline providers. That world is gone.

While high-bandwidth applications have proliferated, so too have the technologies for delivering them. Today, new wireline broadband networks are largely made up of fiber optic cables; traditional cable has enhanced its own capabilities; 5G has become an in-home, not just mobile, option; and LEO satellites are providing high-speed, low-latency broadband, including to places that have never had it before. While all these technologies can complement each other in an overall connectivity ecosystem, they also offer comparable broadband for how most consumers use the Internet. This substitutability has important implications for competition and regulatory policy.

What Makes Broadband Technologies Substitutes

The consumer experience is the ultimate metric for whether a broadband connection is good enough. If a consumer wouldn’t have a worse experience accessing their applications of choice with one technology versus another, then those technologies are substitutes. This evaluation should also incorporate price-quality trade-offs: a lower-quality technology at a lower price that can still provide adequate connectivity for a consumer’s applications of choice is still a viable substitute for more expensive technologies with more capabilities that a consumer does not think are worth the price.

This approach is more realistic and consumer focused than setting arbitrary cardinal numerical definitions of broadband that climb upward for political or marketing reasons unconnected to how consumers actually use the Internet. Just as we don’t consider someone who has a Toyota Camry to be any less capable of driving on the highway than someone who has a Lamborghini, we shouldn’t gerrymander the definition of broadband without reference to actual use cases. The important thing is that they can both reach the speeds necessary to drive where they want to go.

Consumer experience is the ultimate metric for whether a broadband connection is good enough.

Comparing the Performance of Different Technologies

The Federal Communications Commission’s (FCC’s) current definition of broadband—100 megabits per second (Mbps) download and 20 Mbps upload (100/20)—is one such arbitrary definition. The 20 Mbps upload metric is especially problematic because it often ends up excluding terrestrial wireless and LEO satellite services even if they could meet all consumers’ needs. Regardless, we use the 100/20 benchmark in this analysis because it provides a conservative estimate of today’s broadband capabilities and is used by data sources that are otherwise most complete.

The most common consumer broadband technologies today routinely meet or exceed the 100/20 metric. It is important to note that a consumer broadband connection often relies on a number of different technologies both within the last-mile Internet service provider’s (ISP’s) network and across the Internet backbone used to deliver data from across the world. Furthermore, ISPs will offer services at various speed tiers that may fall below the full capabilities of the technology they use. This practice is a way of managing overall network capacity and providing consumers with reasonable certainty that they will get the experience they pay for. Furthermore, technological advances continue with all technologies. For example, DOCSIS 4.0 continues to roll out faster cable speeds, 6G will bring greater FWA capacity and coverage, and next-generation LEO satellites promise gigabit speeds.[1]

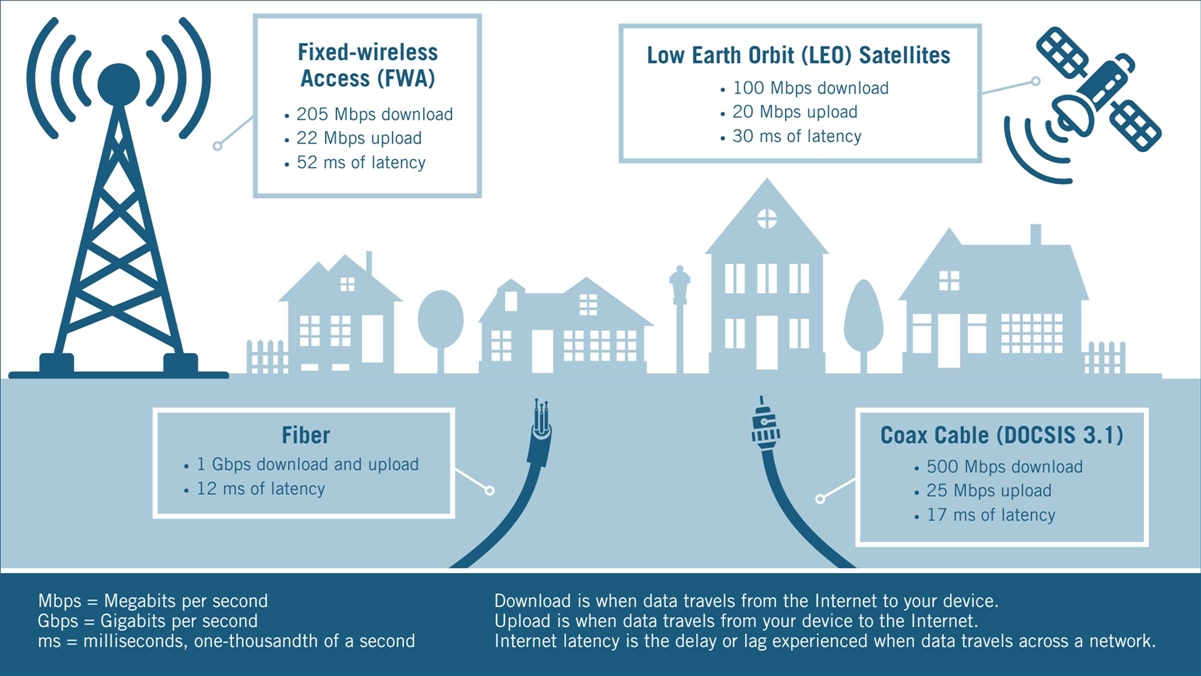

Taking a snapshot in time, therefore, here are some general benchmarks for expected performance of home broadband connections using different technologies:

▪ Fiber: 1 Gigabit per second (Gbps) download and upload, and 12 milliseconds (ms) of latency[2]

▪ FWA: 205 Mbps download, 22 Mbps upload, and 52 ms of latency[3]

▪ Cable (using DOCSIS 3.1): 500 Mbps download, 25 upload, and 17 ms of latency[4]

▪ LEO satellites: 100 Mbps download, 20 Mbps upload, and 30 ms of latency[5]

Figure 1: Types of broadband technologies and their expected performance

Compare these capabilities with the recommended Internet speeds for common applications:

▪ Netflix recommends a minimum download speed of 15 Mbps for 4K video streaming.[6]

▪ Zoom recommends a minimum of 4 Mbps symmetrical (both download and upload) for HD group video calling.[7]

▪ For basic activities such as sending emails and browsing the web, a speed of 1 Mbps is recommended.[8]

▪ Playing Roblox requires at least 5 Mbps download for an optimal experience.[9]

▪ Twitch streaming requires around 8 Mbps upload.[10]

Household bandwidth calculator: Select the number of devices that will be using each application simultaneously to find out which broadband technologies support your household's needs

The New Bottleneck: Home Networking

Lurking in the background of all broadband performance comparisons is what happens to the capacity once it gets into the consumer’s walls. Most often, a router or router-modem combo is the main consumer interface, and most devices will connect to it with Wi-Fi. These steps from the ISP’s network to the consumer’s device are potential bottlenecks.[11] Depending on how applications use data, congestion in the router can have significant impacts on consumers’ experience.[12] For online gaming, for example, low latency and a consistent flow of data are more important than massive throughput at any given time. If other applications, such as 4K video, are pulling large amounts of data all at once in order to buffer a stream, that could cause congestion that would not be alleviated by a higher speed broadband subscription.

Wi-Fi is a flexible technology that uses unlicensed spectrum to connect many types of devices in a home network.[13] To maximize its capabilites, however, consumers must understand its limitations. Wi-Fi largely uses the 2.4 and 5 gigahertz (GHz) bands with 6 GHz devices beginning to roll out too.[14] As with any wireless technology, Wi-Fi transmissions are subject to the laws of physics. Lower frequencies travel further than high frequencies and better penetrate walls, but they also have lower capacity and, in the case of the 2.4 GHz band, have been in use for so long that they are often congested in densely populated areas. On the other hand, higher frequencies, such as 5 and 6 GHz, have great capacity and offer wide channels without much competition, but they will also have more trouble reaching every corner of a large house or one with thick walls. There are technical solutions to many of these trade-offs, ranging from low-tech (e.g., putting a router in a central location rather than an enclosed corner closet) to more advanced solutions such as mesh networking and more extensive in-building wiring.[15]

While ISPs can and should help customers set up a home network that will maximize their connections, competition policy should differentiate between ISP-side and consumer-side bottlenecks. Treating any “slow” connection as a problem with an ISP or the ISP market in general will be more likely to undermine ongoing investment in network capacity than benefit consumers.

More Substitutes Have Led To More Competition

The competition between broadband providers using different technologies has become fierce. The overlay of new technologies on top of existing wireline deployments is a significant competitive development. But competition is not just about the number of competitors in a market. Rather, given two substitutable broadband options, consumers will generally choose the lower-price option. The broadband service itself is not very differentiated between providers. Under such circumstances, even a small number of ISPs will behave in a competitive fashion if they have sufficient capacity and are substitutes from consumers’ perspective.[16] In short, the combination of entry of new competitors alongside the fact that any of those choices could deliver the same user experience to most consumers is the source of competition.

More People Have More Options

While the number of providers alone doesn’t dictate competition or consumer benefit, the presence of at least two ISPs with sufficient capacity will generally lead to competitive pressure to offer lower prices or otherwise differentiate offerings.

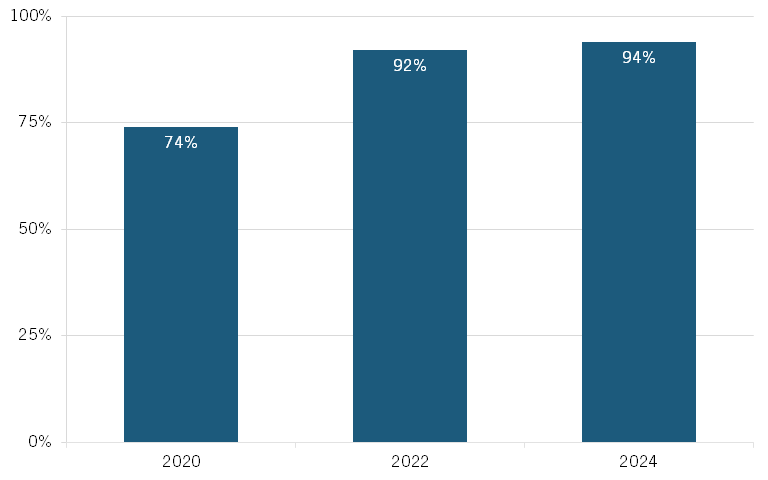

The number of consumers with multiple options is increasing. Over the last four years, the number of Broadband Serviceable Locations (BSLs) that have at least two providers offering 100/20 speeds has increased by 20 percent, meaning 94 percent of BSLs have at least two choices.[17] While the FCC reports this data without including satellite broadband providers that meet the performance benchmarks, it notes that LEO satellite service with 100/20 service covers every BSL; therefore, we have added one to the number of providers in each area.[18]

Figure 2: Percentage of all BSLs with at least two providers offering 100/20 Mbps service[19]

This data comes from the FCC’s Form 477, which, despite being the most recent and comprehensive source available, has limitations. Because it inquires about coverage by census block, it can overstate availability if an ISP is capacity constrained or has only partially deployed within a census block. Nevertheless, we are confident that there are multiple providers offering sufficient speeds for the vast majority of BSLs, and this fact is reflective of a competitive marketplace.

The combination of entry of new competitors alongside the fact that any of those choices could deliver the same user experience to most consumers is the source of competition.

Evidence of Consumers’ Switching Between Options

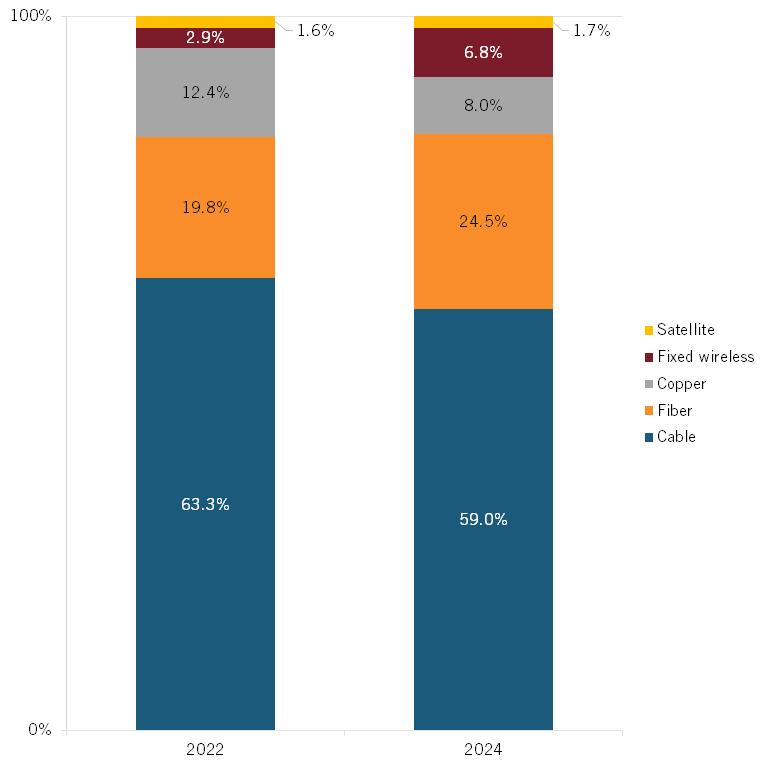

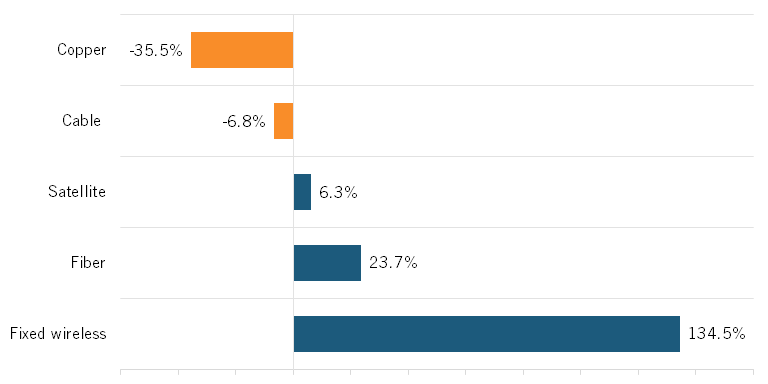

Even as original cable and telephone networks have increased their capacity and been supplemented or replaced by fiber, other technologies are challenging their dominance. If these technologies are legitimate competitors to wireline options, we should expect to see them make inroads to cable and fiber market share. And that’s exactly what we find: Data from the FCC shows that, over a two-year period, FWA’s share of the market more than doubled, and while satellite connections did not increase much as a relative share of the market in this time period, Starlink, which started taking customers in 2021, went from zero subscribers to nearly 2 million over a three-year period.[20]

Figure 3: Shares of U.S. broadband connections by technology, 2022 and 2024[21]

Figure 4: Percentage change in shares of U.S. broadband connections by technology, from 2022 to 2024[22]

Cable companies have seen a substantial decline in customers, as reflected by the 4 percentage point drop in the chart above. The largest cable companies have lost hundreds of thousands of subscribers to competitors in the last year alone.[23] This change shows that cable’s long-time dominance is fading due to new alternatives entering the market or existing companies expanding their footprint and capacity. Importantly, however, an ISP’s market share is not necessarily indicative of market power. If an ISP can keep its customers only by keeping prices low, that is a competitive outcome even if it does in fact keep those customers. So while erosion of market share is evidence of competition, it would not necessarily be a reversal of competition if cable were to regain ground.

Lack of Monopoly Profits

Profit margins for the broadband industry can be indicative of a competitive market for Internet service. If the market were not competitive and ISPs exercised considerable market power, we would expect them to earn profits well above average for the competitive U.S. economy.[24] Data compiled by Professor Aswath Damodaran shows that the current net profit margin across U.S. industries is 8.7 percent, and the average for the U.S. broadband industry is 7 percent.[25] In other words, even if all profit were competed away, broadband prices would fall by only 7 percent.

And really, there is even less margin than that. The resources expended to provide broadband service could be invested in other projects. As soon as the rate of return on broadband falls below the rate of return of the next best alternative use, the broadband network is not net profitable from an economic perspective. Therefore, we should not expect broadband networks to be sustainable unless their profits are well above the rate of return of safer investments, such as Treasury bonds.

Profit-seeking companies don’t offer lower prices than they have to or give away other products without expecting return, so extensive promotions are a sign that ISPs believe that they will lose customers if they don’t keep up with the competition.

Evidence of Competitive Pressure: Promotional Rates and Programs

Another piece of evidence of broadband competition is the extensive promotions ISPs are now offering to try to attract customers. Profit-seeking companies don’t offer lower prices than they have to or give away other products without expecting return, so extensive promotions are a sign that ISPs believe that they will lose customers if they don’t keep up with the competition. While prices vary widely across the country, $63/month is the median price across a sample of 250 different service plans for all available speeds.[26] But today, ISPs routinely offer far lower prices and attempt to differentiate their services by offering other valuable benefits. Some current examples:

1. Comcast’s five-year, $55 per month price lock with no annual contract allows customers to cancel at any time.[27]

2. Spectrum offers home Internet and two unlimited mobile lines for $30 per month with a two-year price lock guarantee and free Wi-Fi equipment.[28]

3. Verizon ran a limited-time offer in May and June wherein if customers signed up for a 5G home Internet plan, they could lock in the $35 price (for the lowest-speed tier) for 3 years and receive a Nintendo Switch after maintaining the service for at least 65 days.[29]

4. T-Mobile offers $300 cash-back, a Netflix subscription, and a five-year price lock guarantee on plans starting at $50 per month for new customers.[30]

5. Optimum offers cash back up to $400 and an iPhone 16 with a trade-in for their Internet & Mobile and Internet & Mobile & TV bundles starting at $40 per month.[31]

6. AT&T’s new service guarantee promises customers a bill credit for a full day of service in the event of a service outage lasting more than 20 minutes, no equipment charges, and same-day technician service.[32]

This dynamic of undercutting competitors and finding other methods of differentiating on price is indicative of a competitive marketplace. Notably, many promotions come without contractual obligations to stay with an ISP, so these promotions are more likely signs of competitive pressure, not loss leaders to lock in customers.

Policies Are Out of Step With Today’s Competitive Marketplace

Regulations have grown up alongside broadband technologies, but policies created for siloed marketplaces of video, telephone, and mobile service have become less rational and less necessary as convergence and competition have produced pro-consumer outcomes. Today, legacy regulations are more likely to hold back the development of a competitive marketplace than foster it. Out-of-step policies and regulations come from many directions; the following are some of the most egregious.

Rate Regulation Is Inapt and Ineffective

In a competitive marketplace, market prices effectively drive resources to productive uses and produce pro-consumer outcomes. But rather than let the market work, some states are pursuing broadband rate regulation. These efforts are a poor fit for today’s market and ultimately counterproductive for broadband affordability.

The primary example of state-level rate regulation is New York’s 2021 Affordable Broadband Act, which limits the amount that ISPs can charge for service to $15 per month.[33] After being blessed by the courts, it took effect in January 2025. A similar law, also with a $15 cap, was introduced in the California legislature around the same time.[34]

The unstated premise behind these proposals is that broadband prices could be lower and still preserve the quality of service and investments needed to grow networks to accommodate future consumer needs. But this premise is false. As shown, ISP profits are relatively low; they are not earning monopoly rents that could be substantially diminished while also covering the costs of widespread deployment and ongoing improvements.

Profit-seeking ISPs make decisions on the margin: they try to make every transaction for which their expected benefit exceeds their expected cost. Capping that expected benefit by regulating rates also caps the costs an ISP will be willing to incur to provide new services or upgrade existing networks.

Moreover, U.S. broadband prices reflect the competitive marketplace, falling well within the recognized benchmark for affordability.[35] To be sure, affordable average prices do not mean that every household can afford broadband. There is a strong case for giving low-income households assistance to make broadband affordable: the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) has proposed a $30 per month voucher for households at 135 percent or less of the Federal Poverty Level.[36]

This proposal would make broadband affordable for low-income households in a way that rate regulation does not. No matter how low the regulated rate, there will always be a subset of people who cannot afford it, while at the same time there would be a dramatic reduction in revenue from well-off households that would otherwise cover maintenance and expansion costs. That's why giving vouchers for market-rate service to households that truly need them is more effective than rate regulation.

Ongoing Rural Broadband Subsidies Are Obsolete

Since the Internet became an essential part of everyday life, much of broadband policy has revolved around how to fund deployment of broadband infrastructure to remote areas, which are inherently expensive to reach with wireline technology. One of the biggest programs directed toward this problem is the FCC’s High-Cost Fund, which averages $4.8 billion in spending per year.[37] But as broadband has expanded deeper into rural areas and new technologies are reducing the number of areas that cannot be reached economically, the High-Cost Fund has become obsolete.[38] Yet, it continues to spend billions of dollars per year to prop up less-economical deployments that still need subsidies for their operating expenses even after having already received subsidies for their capital expenses.

By subsidizing only traditional technologies to reach areas that they cannot profitably sustain, the High-Cost Fund undermines profit opportunities for someone who can invent a way of serving those areas sustainably. LEO satellites appear to be those inventions for many remote areas.[39] But LEO ISPs have been excluded from High-Cost Fund subsidies.[40] So not only does the High-Cost Fund undermine long-run sustainable deployment, but it also subsidizes exclusively the competitors of the sustainable solution. That thumb on the scale is incompatible with market realities in which technological advancements and fair competition, not government subsidies, are expanding consumers’ options. Congress and the FCC should sunset the High-Cost Fund and reprioritize all FCC funding programs to focus on the remaining causes of the digital divide.[41]

As long as the license holder is still legally responsible for ensuring compliance with the terms of its license, there should be no usage limitations.

Productive and Flexible Spectrum Allocation Is Essential

Because many new competitors in the broadband market are wireless ISPs, the availability of electromagnetic spectrum to provide broadband services is a potential ceiling for consumer benefits. If FWA (using licensed or unlicensed spectrum) or LEO providers only have enough spectrum to serve a small number of customers, then the breadth of the competitive pressure they exert on other ISPs will be limited. Allocating more spectrum for commercial use is therefore an essential step in maintaining and expanding the benefits of converging home-broadband technologies. Today, the bulk of midband spectrum (which is most useful for home broadband) is controlled by the federal government.[42] Executive-branch leadership, legislative oomph, and FCC initiative will be crucial in identifying federal spectrum that could be more productive in commercial uses while also protecting and enhancing critical federal missions. The alternative of federal spectrum hoarding is a drag on broadband competition.

When making new commercial allocations, the FCC should take account of how changing technological realities affect the concept of flexible use, which means the FCC sets basic technical rules to manage harmful interference within a spectrum band without mandating the particular applications the band can support.[43] The FCC has been moving in the direction of more flexibility, especially in the mobile marketplace. But in an age of LEO satellites, terrestrial-only flexibility is insufficient. The FCC has taken note of this fact with its Supplemental Coverage From Space proceeding, which allows terrestrial mobile licensees to use their spectrum for satellite service as well under other certain circumstances.[44] But rather than being a special case, this kind of flexibility should be the norm: all terrestrial mobile spectrum should be allowed to be used by satellites without FCC permission.[45] As long as the license holder is still legally responsible for ensuring compliance with the terms of its license, there should be no usage limitations. This change would expand the possible uses of future spectrum allocations and create new opportunities for satellite use of existing terrestrial mobile spectrum, further enhancing the potential for consumers to benefit from these new technologies.

Title II for Broadband Should Be Rejected Permanently

Twice in the last decade, the FCC has sought to regulate broadband under Title II of the Communications Act. Title II is the regulatory framework designed for the old telephone monopoly. It is therefore inapt for the competitive broadband marketplace. Market outcomes are not independent of the regulations that shape them; a regulatory regime designed for monopoly will be likely to produce the kinds of sclerotic outcomes and diminished investment one would expect from a genuine monopoly.

While it was always misguided, today, Title II advocacy is transparently anticonsumer.

Recently, a federal court declared that the application of Title II to broadband is inconsistent with the Communications Act, and the current FCC chairman is unlikely to attempt to reapply it. But insofar as Title II proponents are waiting for their chance to try again, they should abandon that ideological crusade and recognize that the competitive broadband market is serving consumers better than utility-style regulation is. While it was always misguided, today, Title II advocacy is transparently anticonsumer.

The Case for Government-Owned Networks Diminishes and Private Competition Increases

Prior ITIF analysis has defined the circumstances in which a government-owned network (GON) is a good policy choice.[46] The developments in the broadband market previously described reduce the circumstances that satisfy the third prong of that test: the growth and development in the private home broadband market has diminished the areas unserved by private ISPs. As technology reaches more unserved areas with higher quality service, local governments should enable their deployment by eliminating regulatory barriers rather than taxing their citizens to fund a GON that can only survive through special treatment not afforded to the private sector.[47]

Regulatory Silos Are Outdated

Much regulation of the broadband industry has grown from legacy regulations of particular technologies. The cable industry, for example, is subject to federal and state regulations intended to force wide deployment of linear video by a single provider.[48] But these regulations make little sense in a world in which cable providers are basically ISPs competing against other ISPs that use different technologies.

Likewise, legacy carrier-of-last-resort rules often divert funds to maintain obsolete infrastructure when technological developments could give consumers continuity of coverage while allowing capital to flow to expanding and enhancing more advanced networks for all consumers.[49]

Evidence of out-of-date siloing is visible in the structure of the FCC, which dedicates an entire bureau to “Wireline Competition.” That distinction is essentially meaningless. In today’s multimodal, highly competitive marketplace, technology-specific competition regulation distorts regulators’ view of the market, which is more likely to encourage regulatory mission creep than benefit consumers.[50]

Mergers Could Benefit Broadband Consumers

The data presented herein suggests that there could be consumer benefits from mergers in the broadband marketplace. The broadband industry is capital intensive: ISPs must invest a lot of money to deploy and maintain their network infrastructure so they can offer competitive service quality and prices. To stay in business, therefore, ISPs need to sell their product to a substantial share of the marketplace, earning a small profit from large number of customers.

Suppose ISPs need to sell their product to at least 40 percent of the customers in their service area to cover their fixed costs. This fact, combined with the fact that households generally buy only one home broadband subscription, means that no more than two ISPs can sustainably serve the same market.

Rather than silos for home and mobile connectivity with a nascent satellite component on the side, ISPs may need to become generalized connectivity companies that offer fixed and mobile service everywhere all the time by means of wires, terrestrial wireless, and satellite components.

The particular market share will vary based on the magnitude of an ISP’s fixed costs, but it is not the case that adding more and more ISPs will always drive prices down. Instead, mergers between ISPs may be the best way to reduce fixed costs and give consumers the benefits of sustainable networks.

Technological convergence may also push ISPs to reconceptualize their offerings in a way that restructures the market. Rather than silos for home and mobile connectivity with a nascent satellite component on the side, ISPs may need to become generalized connectivity companies that offer fixed and mobile service everywhere all the time by means of wires, terrestrial wireless, and satellite components. Unifying these components into one offering would be a more efficient way of providing them and, therefore, result in lower consumer prices in a competitive marketplace than purchasing each component separately would.[51]

We are already seeing this kind of market convergence with agreements between market participants to provide these kinds of integrated services, with cable companies leasing spectrum from mobile operators to offer their own mobile service that can be bundled with a wireline home broadband service.[52] Mobile providers have also partnered with satellite companies to provide connectivity in even the most remote areas.[53]

Conclusion

Technological convergence has fundamentally reshaped the U.S. broadband landscape, creating a competitive marketplace that continues to evolve to the benefit of consumers. This transformation represents a success story for market-driven innovation, wherein private investment and technological advancement have delivered expanded consumer choice and competitive pricing without extensive regulatory intervention.

The policy implications of this competitive transformation demand comprehensive regulatory realignment. Legacy rules now actively undermine the competitive dynamics that best serve consumers. Instead of perpetuating interventions designed for a fundamentally different market structure, policymakers should focus on enabling competitive outcomes through recognition that strategic industry consolidation would enhance rather than diminish consumer benefits. The convergence in the broadband marketplace demonstrates that when regulatory frameworks align with technological and market realities, American consumers benefit from expanded choice, improved service quality, and competitive pricing.

About the Authors

Joe Kane is director of broadband and spectrum policy at ITIF. Previously, he was a technology policy fellow at the R Street Institute, where he covered spectrum policy, broadband deployment and regulation, competition, and consumer protection. Earlier, Kane was a graduate research fellow at the Mercatus Center, where he worked on Internet policy issues, telecom regulation, and the role of the FCC, where he interned in the office of Chairman Ajit Pai. He holds a J.D. from The Catholic University of America, a master’s in economics from George Mason University, and a bachelor’s in political science from Grove City College.

Ellis Scherer is a research assistant at ITIF covering broadband and spectrum policy. He previously interned with the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) and worked as a cybersecurity consultant. He holds a master’s degree in terrorism and homeland security policy from American University and a bachelor’s degree in politics and history from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

About ITIF

The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) is an independent 501(c)(3) nonprofit, nonpartisan research and educational institute that has been recognized repeatedly as the world’s leading think tank for science and technology policy. Its mission is to formulate, evaluate, and promote policy solutions that accelerate innovation and boost productivity to spur growth, opportunity, and progress. For more information, visit itif.org/about.

Endnotes

[1]. Jessica Dine, “ITIF Technology Explainer: DOCSIS 4.0” (ITIF, August 28, 2023), https://itif.org/publications/2023/08/28/itif-technology-explainer-docsis4/; Francesco Pica and Dr. Lola Awoniyi-Oteri, “Path to 6G: Envisioning next-gen use cases for 2030 and beyond,” Qualcomm, https://www.qualcomm.com/news/onq/2024/06/path-to-6g-envisioning-next-gen-use-cases-for-2030-and-beyond; Michael Kan, “SpaceX Preps New Starlink Dishes, Including One for Gigabit Speeds,” PCMag, March 24, 2025, https://www.pcmag.com/news/spacex-preps-new-starlink-dishes-including-one-for-gigabit-speeds.

[2]. Kate Fan, “DSL vs. Cable vs. Fiber: What’s the Best Wired Internet?” BroadbandNow, May 30, 2025, https://broadbandnow.com/guides/dsl-vs-cable-vs-fiber; “Performance Characteristics,” AT&T, accessed June 3, 2025, https://about.att.com/sites/broadband/performance.

[3]. Sue Marek, “In a boost of confidence for FWA, both T-Mobile and Verizon announced plan to expand their service beyond their initial subscriber targets,” Ookla, March 24, 2025, https://www.ookla.com/articles/fwa-gets-robust-speeds.

[4]. Fan, “DSL vs. Cable vs. Fiber: What’s the Best Wired Internet?”; “Cox Internet Service Disclosures,” Cox, updated December 16, 2024, https://www.cox.com/aboutus/policies/internet-service-disclosures.html.

[5]. “Starlink Specifications,” Starlink, accessed June 3, 2025, https://www.starlink.com/legal/documents/DOC-1470-99699-90; “Starlink Map,” Starlink, accessed June 3, 2025, https://www.starlink.com/map.

[6]. “Netflix-recommended internet speeds,” Netflix, accessed May 28, 2025, https://help.netflix.com/en/node/306#:~:text=Table_title:%20Netflix%2Drecommended%20internet%20speeds%20Table_content:%20header:%20%7C,Recommended%20speed:%2015%20Mbps%20or%20higher%20%7C.

[7]. “Zoom system requirements: Windows, macOS, Linux,” Zoom, accessed May 28, 2025, https://support.zoom.com/hc/en/article?id=zm_kb&sysparm_article=KB0060748.

[8]. “Network Guidelines” Microsoft, July 3, 2024, https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows-server/remote/remote-desktop-services/network-guidance.

[9]. “Roblox Mobile System Requirements,” Roblox, accessed June 3, 2025, https://en.help.roblox.com/hc/en-us/articles/203625474-Roblox-Mobile-System-Requirements.

[10]. “How Do I Stream FAQ,” Twitch, accessed June 3, 2025, https://help.twitch.tv/s/article/how-do-i-stream-faq?language=en_US.

[11]. Speed Test, “Understanding Internet Speeds: What’s Delivered vs. What You Experience,”Ookla, accessed June 4, 2025, https://www.speedtest.net/about/knowledge/understanding-internet-speeds.

[12]. The Vault, “Broadband Network Congestion: A Complete Guide,” OpenVault, accessed June 4, 2025, https://openvault.com/resources/the-vault/broadband-network-congestion-a-complete-guide-openvault/#:~:text=Causes%20of%20Network%20Congestion,sufficient%20resources%20to%20prevent%20congestion.

[13]. Kate Lohnes, “How Does Wi-Fi Work?” Britannica, accessed June 4, 2025, https://www.britannica.com/story/how-does-wi-fi-work.

[14]. Ibid.

[15]. Whitson Gordon, “10 Pro Tips To Boost Your Wi-Fi Signal,” PC Mag, updated February 18, 2025, https://www.pcmag.com/how-to/10-ways-to-boost-your-wi-fi-signal.

[16]. Mike Walker “Bertrand-Nash Equilibrium,” Concurrences, accessed October 7, 2024, https://www.concurrences.com/en/dictionary/bertrand-nash-equilibrium.

[17]. Office of Economics and Analytics, Internet Access Services: Status as of June 30, 2024 (Washington DC: FCC, May 2025), 9, https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/DOC-411463A1.pdf; Office of Economics and Analytics, Internet Access Services: Status as of June 30, 2022 (Washington DC: FCC, May 2024), 9, https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/DOC-402310A1.pdf; Office of Economics and Analytics, Internet Access Services: Status as of June 30, 2020 (Washington DC: FCC, August 2023), 6, https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/DOC-395961A1.pdf.

[18]. “Starlink Map,” Starlink, accessed June 11, 2025, https://www.starlink.com/map.

[19]. Office of Economics and Analytics, Internet Access Services: Status as of June 30, 2024, https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/DOC-411463A1.pdf; Office of Economics and Analytics, Internet Access Services: Status as of June 30, 2022, https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/DOC-402310A1.pdf; Office of Economics and Analytics, Internet Access Services: Status as of June 30, 2020, https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/DOC-395961A1.pdf.

[20]. Joe Supan, “The Rise and Inevitable Downfall of 7,000 Starlink Satellites,” Broadband Breakfast, February 19, 2025, https://broadbandbreakfast.com/joe-supan-the-rise-and-inevitable-downfall-of-7-000-starlink-satellites/.

[21]. Office of Economics and Analytics, Internet Access Services: Status as of June 30, 2024, https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/DOC-411463A1.pdf; Economics and Analytics, Internet Access Services: Status as of June 30, 2022, https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/DOC-402310A1.pdf.

[22]. Ibid.

[23]. Jake Neenan, “Charter Broadband Losses Better Than Expected,” Broadband Breakfast, November 1, 2024, https://broadbandbreakfast.com/charter-broadband-losses-better-than-expected-2/?ref=alerts-newsletter; Jon Brodkin, “Comcast president bemoans broadband customer losses: ‘We are not winning,’” Ars Technica, April 24, 2025, https://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2025/04/after-losing-customers-comcast-admits-prices-are-too-confusing-and-unpredictable/.

[24]. Hadi Houalla and Aurelien Portuese, “The Great Revealing: Taking Competition in America and Europe Seriously” (ITIF, May 2023), https://www2.itif.org/2023-us-eu-competition.pdf.

[25]. Using a weighted average of wireline and wireless firms; satellite margins are not available. “US Operating and Net Margins by Industry Sector,” Damodaran Online, 2025, https://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~adamodar/pc/datasets/margin.xls.

[26]. Joe Supan, “The Average Monthly Cost of Internet is $78. Here’s How to Lower It,” CNET, May 24, 2025, https://www.cnet.com/home/internet/the-average-monthly-cost-of-internet-is-78-heres-how-to-lower-it/.

[27]. “Comcast Launches Five-Year Price Guarantee for Xfinity Internet Customers,” Comcast, April 15, 2025, https://corporate.comcast.com/press/releases/comcast-launches-five-year-guarantee-for-xfinity-internet-customers.

[28]. David Anders, “Best Internet and Mobile Bundles for May 2025,” CNET, May 5, 2025, https://www.cnet.com/home/internet/best-internet-and-mobile-bundles/.

[29]. “Get the Nintendo Switch system, on us with any Verizon Home Internet plan,” Verizon, accessed May 29, 2025, https://www.verizon.com/home/internet/.

[30]. “Home Internet Deals,” T-Mobile, accessed May 29, 2025, https://www.t-mobile.com/home-internet/deals?INTNAV=tNav%3AInternetDeals.

[31]. “Bundles,” Optimum, accessed May 30, 2025, https://www.optimum.com/bundles.

[32]. “AT&T Unveils First & Only Customer-First Promise Across Both Wireless & Fiber Networks; Plus, Customer Care & Deals,” AT&T, January 8, 2025, https://about.att.com/story/2025/guarantee.html.

[33]. Broadband Service for Low-Income Consumers, 2021-A6259, New York State Assembly. (2021). https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2021/A6259/amendment/original.

[34]. California Affordable Home Internet Act of 2025, California State Assembly. (2025). https://legiscan.com/CA/text/AB353/id/3229482.

[35]. Joe Kane, “A Blueprint for Broadband Affordability” (ITIF, January 13, 2025), https://itif.org/publications/2025/01/13/a-blueprint-for-broadband-affordability/.

[36]. Ibid.

[37]. Joe Kane, “Sustain Affordable Connectivity by Ending Obsolete Broadband Programs” (ITIF, July 17, 2023), https://itif.org/publications/2023/07/17/sustain-affordable-connectivity-by-ending-obsolete-broadband-programs/.

[38]. Ibid.

[39]. Kane, “A Blueprint for Broadband Affordability.”

[40]. Wireline Competition Bureau, In the Matter of Rural Digital Opportunity Fund and Rural Digital Opportunity Fund (Auction 904) Order on Reconsideration (Washington DC: Federal Communications Commission WC Docket No. 19-129 and Docket No. 20-34, August 30 2024), https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/DA-24-883A1.pdf.

[41]. Kane, “A Blueprint for Broadband Affordability.”

[42]. “United States Frequency Allocation Chart,” National Telecommunications and Information Administration, accessed June 12, 2025, https://www.ntia.doc.gov/files/ntia/publications/2003-allochrt.pdf.

[43]. Joe Kane, “Five Principles for Spectrum Policy: A Primer for Policy Makers” (ITIF, September 6, 2022), https://www2.itif.org/2022-spectrum-principles-primer.pdf.

[44]. Single Network Future: Supplemental Coverage from Space; Space Innovation (Washington DC: FCC, GN Docket No. 23-65 and IB Docket No. 22-271, April 30, 2024, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2024-04-30/pdf/2024-06669.pdf.

[45]. Joe Kane and Ellis Scherer, “Comments to the FCC Regarding the Upper C-Band” (ITIF, April 20, 2025), https://itif.org/publications/2025/04/30/comments-to-fcc-regarding-upper-c-band/.

[46]. Ellis Scherer, “Government-Owned Broadband Networks Are Not Competing on a Level Playing Field” (ITIF, December 2, 2024), https://itif.org/publications/2024/12/02/government-owned-broadband-networks-are-not-competing-on-a-level-playing-field/.

[47]. Ibid.

[48]. Joe Kane, Jeffrey Westlin, and Thomas Stuble, “2018 Broadband Scorecard Report” (R-Street, November 29, 2018), https://www.rstreet.org/research/2018-broadband-scorecard-report/.

[49]. Ellis Scherer, “California Should Modernize Its Carrier-of-Last-Resort Requirements,” ITIF Innovation Files commentary, June 23, 2025, https://itif.org/publications/2025/06/23/california-should-modernize-its-carrier-of-last-resort-requirements/.

[50]. Kane and Scherer, “Comments to the FCC Regarding Identifying and Eliminating Unnecessary Rules and Regulations.”

[51]. Alex Tabarrok, “Double Marginalization Problem,” Marginal Revolution University, September 14, 2015, https://mru.org/courses/development-economics/double-marginalization-problem.

[52]. Mike Dano, “Verizon inks ‘expanded and extended’ MVNO deals with Comcast, Charter,” Light Reading, November 11, 2020, https://www.lightreading.com/5g/verizon-inks-expanded-and-extended-mvno-deals-with-comcast-charter.

[53]. “Satellite with Starlink,” T-Mobile, accessed June 12, 2025, https://www.t-mobile.com/coverage/satellite-phone-service.

Editors’ Recommendations

January 13, 2025

A Blueprint for Broadband Affordability

August 28, 2023

ITIF Technology Explainer: What Is DOCSIS 4.0?

September 6, 2022

Five Principles for Spectrum Policy: A Primer for Policymakers

April 30, 2025

Comments to the FCC Regarding the Upper C-Band

Related

September 3, 2019

A Policymaker’s Guide to Broadband Competition

November 21, 2008