“Big Pharma” Is a Normal Industry

President Trump has announced his intention to regulate U.S. drug prices. But the arguments in favor of doing so are wrong. Price controls reduce development of new treatments and cures, and hurt U.S. biopharmaceutical competitiveness.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Key Takeaways

Contents

Introduction

“Big Pharma” has long been a target of the anti-capitalist, left populists who want to transform the sector by imposing strict price controls, weakening patents, and/or instituting a government-run drug development system, all of which would slow the development of important new drugs.

The calls for radical change are legion. The liberal Center for American Progress has proposed a wide array of policies to reduce drug prices, including price controls and reducing the period of data exclusivity (the time which companies can keep data proprietary).[1] Progressive economist Dean Baker has urged lawmakers to “expand the public funding going to NIH or other public institutions and extend their charge beyond basic research to include developing and testing drugs and medical equipment.”[2] Liberal commentator Robert Reich has proposed reducing drug patent terms from 20 years to three, while Knowledge Ecology International, a leading drug populist organization, wants to eliminate drug patents, especially in developing economies.[3] (Eliminating patents would make available more generic versions of today’s drugs, but alas, few new drugs.)

Now the new populist, anti-corporate right under President Trump’s leadership is making the same proposals, particularly when it comes to drug pricing. Trump wants to implement international reference pricing whereby drugs in the U.S. would be priced at the same level as other countries that impose drug price controls.

If the populists can show the free-market system has failed, then fundamentally transforming the biopharma industry becomes much easier. But the facts show otherwise.

To justify such a dramatic shift, both left and right proponents need to discredit the current private-sector-led model that has made America the world leader in pharma and biopharma innovation.[4] They must convince policymakers and the public that the drug industry no longer serves the public interest of effectively delivering new drugs. To do this, they claim that the industry earns excess profits from rapidly rising drug prices, spends too much money on stock buybacks and advertising, and too little on new drug development. If the populists can advance these claims and show that the free-market system has failed, fundamentally transforming the industry becomes much easier. But the facts show otherwise.

Normal Profits

Start with profits. The populists argue that drug prices are high because profits are excessive. Moreover, they claim, there is plenty of money for the industry to develop drugs, even if its revenues are significantly lowered as a result of price controls or reduced intellectual property protection. They rationalize this assertion with claims of excess profits and wasted spending.

U.S. Rep. Katie Porter (D-CA), deputy chair of the Congressional Progressive Caucus, issued a scathing report in 2021 titled “Killer Profits,” attempting to make the case that the industry makes too much money.[5] Two years earlier, the Center for American Progress made the same claim that “Big Pharma Reaps Profits.”[6] More recently, the self-described “democratic socialist” Senator Bernie Sanders (VT), has claimed that “Greedy pharma firms rip off Americans.”[7] Notably, these critiques span the political spectrum. Figures on the right, including President Donald Trump, have voiced similar concerns. Trump stated in January, “We’re the largest buyer of drugs in the world. And yet we don’t bid properly. We’re going to start bidding. We’re going to save billions of dollars over a period of time.”[8]

The reality is that, when adjusting for risk and comparing it to other industries, pharmaceutical firms’ profits are not excessive, nor are drug prices driving up overall health-care expenditures. Researchers Sood, Mulligan, and Zhong compared excess profits of pharmaceutical companies and S&P 500 firms.[9] They defined excess profit as “higher than expected profits given the risk associated with their investments” and found that pharmaceutical companies’ excess profits were actually 1.7 percentage points lower than the 3.6 percent average among S&P 500 firms.[10]

The reality is that, when adjusting for risk and comparing it to other industries, pharmaceutical firms’ profits are not excessive, nor are drug prices driving up overall health-care expenditures.

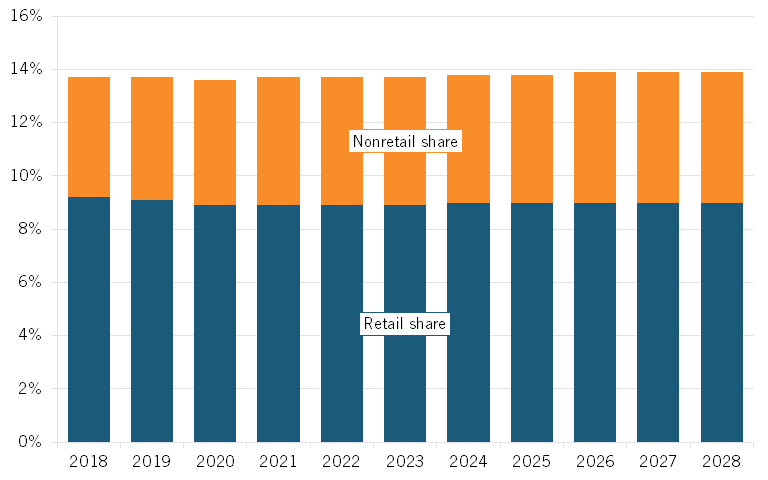

Moreover, an analysis in PLosONE found that pharmaceutical “returns were substantially lower than [those of] the other eight health care industries.”[11] Despite today’s rhetoric, prescription medicines have accounted for only about 14 percent of U.S. health-care spending in recent years, and that share is expected to remain stable going forward.[12] Similarly, the research firm Altarum found in a 2020 report that the retail pharma share will likely remain stable in the 9 percent range through most of this decade, with non-retail expenditures also roughly stable in the 4.5 to 4.9 percent range. (Figure 1.) This puts the United States right in line with other OECD nations.[13]

Yet, over the last 10 years, the annualized return on the Standard & Poor’s (S&P) Biotech Index averaged 7.95 percent and the Pharmaceutical Select Index averaged 3.29 percent, both lower than the S&P 500 index return of 12.49 percent, which undercuts the argument that stock buybacks are being used to “prioritize short term financial returns,” as one article contended.[14]

Figure 1: Projected prescription drug share of national health-care expenditures[15]

When it comes to marketing, the charge is just as specious. An analysis in JAMA Network, which included all promotional activities, physician education, advertising, and unbranded disease awareness campaigns as “medical marketing,” puts the total of these activities (many of which have significant value to patients) at one-third of R&D expenditures.[16] When looking just at pharmaceutical advertising, total spending reached was $6.58 billion in 2020, a small fraction of the $122 billion the industry invested in R&D in the United States that year.[17]

Opponents of large drug companies also claim that the companies are not investing in R&D. The progressive think tank Roosevelt Institute has argued that, “as prices have skyrocketed over the last few decades, these same companies’ investments in research and development have failed to match this same pace.”[18] In reality, from 2012 to 2016, drug sales increased $5.8 billion a year, while R&D actually increased $6.8 billion a year.[19]

America’s pharmaceutical industry is the most R&D-intensive industry in the world, investing over 20 percent of its sales into R&D each year, which accounts for 18 percent of the total U.S. business R&D investment.

Drug companies in America are highly R&D-intensive and have become even more so, with their R&D-to-sales ratio increasing from 11 percent in 2006 to 20 percent in 2018.[20] The ratio for the top 20 U.S. drug companies increased from 15 percent in 2006 to 23.6 percent.[21] Further, while drug revenues increased 56 percent from 2006 to 2018 (in nominal dollars), R&D increased by 85 percent, and it is the largest firms, not the smallest, that are the most R&D intensive.[22] The non-partisan Congressional Budget Office reports that “In 2019, the pharmaceutical industry spent $83 billion dollars on R&D. Adjusted for inflation, that amount is about 10 times what the industry spent per year in the 1980s.”[23]

In fact, America’s pharmaceutical industry is the most R&D-intensive industry in the world, investing over 20 percent of its sales into R&D each year, which accounts for 18 percent of the total U.S. business R&D investment.

Pricing Realities

The populists tell us that prices are rising way too fast because of “corporate greed.” The Kaiser Family Foundation rails that “Prices Increased Faster Than Inflation for Half of all Drugs Covered by Medicare in 2020.”[24] But of course that means that prices increased less than inflation for the other half. Three professors of medicine at Harvard agree, claiming that drug prices are “skyrocketing.”[25]

To be sure, there are cases where individuals confront large and sudden medical bills: One study found that nearly 40 percent of commercially insured individuals incurred half of their annual out-of-pocket drug spending on one purchase, and 26 percent incurred 90 percent of their annual health-care spending in only one or two encounters.[26] (This is why policies such as “smoothing” Medicare beneficiaries’ out-of-pocket costs over the course of a year are often warranted.)[27] Yet overall, the data shows that American consumers’ out-of-pocket expenditures on drugs over the past two decades have grown much less than their overall health-care and health insurance expenditures.

Furthermore, the distinction between net prices and list prices is critical because while list prices may be on the rise, the share of expenditures being paid to drug manufacturers in recent years is lower than before. For instance, Andrew Brownlee at the Berkeley Research Group found that the share of revenues accruing to drug manufacturers for all drugs decreased by over 17 percentage points from 2013 to 2020, from 66.8 percent to 49.5 percent, while the share going to intermediaries (wholesalers, pharmacies, PBMs, and insurance companies) increased from 33.2 to 50.5 percent.[28]

American consumers’ out-of-pocket expenditures on drugs over the past two decades have grown much less than their overall health-care and health insurance expenditures.

In other words, less than half of every dollar Americans spend on drugs actually goes to the companies developing and making them. Overall, Brownlee found that brand manufacturers retain just 37 percent of total spending on all prescription medicines.[29] Similarly, researchers at the University of Southern California examined the “net price” of insulin and found that list prices did increase between 2014 to 2018, but that the share of insulin drug sales flowing to manufacturers decreased, with more than half of insulin expenditures going to intermediaries by 2018.[30] Indeed, there has been a 140 percent increase in insulin list prices over the past eight years, but net prices actually declined by 41 percent, casting a new light on Angelis and colleagues’ argument that “old and common drugs” like insulin “have seen inexplicable price increases.”[31]

What about the claim that drugs costs less in many other nations? For example, Senator Josh Hawley (R-MO) has argued, “For too long, Americans have subsidized prescription drug costs for foreigners while paying outrageous prices for their own medications.”[32] While it is generally true that drug prices are lower in other developed countries than in the United States, this is not due to monopoly or market power of U.S. drug companies. The reason is that foreign governments free-ride off American drug innovation by imposing draconian price controls. After adjusting for GDP per capita, 30 of 32 OECD countries had lower prescription drug prices than the United States. These price controls reduced manufacturer revenue in 2018 by 77 percent, or $254 billion. Lifting pharmaceutical price regulations would have resulted in $56.4 billion of additional R&D expenditures and 25 new drugs annually.[33] If just five rich nations—Japan, Germany, France UK, and Italy—had paid their fair share, humanity would have benefited from 12 new drugs every year. It is striking that many countries are willing to sacrifice their economic welfare by paying higher energy prices to save the planet from climate change. Yet, when it comes to curing diseases, they free ride on the investments of the United States.

Why not impose price controls in the United States? We could, but the result would be fewer drugs developed every year. Virtually every peer-reviewed academic paper on the subject finds that drug price controls would mean less R&D and fewer drugs.[34] How could they not as it is sales revenue that funds drug company R&D labs? So rather than impose drug price controls in the United States, U.S. policy makers should press other nations to roll back their controls and contribute their fair share to global drug development.

Early Access

Moreover, by focusing solely on prices, drug populists neglect to mention that Americans enjoy access to innovative medicines far earlier than citizens in other nations do.[35] For instance, 87 percent of new medicines launched globally from 2011 through year-end 2019 were available first in the United States, a wide gap over Germany and the United Kingdom, where only 63 and 59 percent of medicines were available there, with percentages declining to as low as 46 percent in Canada and 39 percent in Australia.[36]

By focusing solely on prices, drug populists neglect to mention that Americans enjoy access to innovative medicines far earlier than citizens in other nations do.

Considering the percentage of drugs available within one year of their global launch, U.S. residents again enjoyed the greatest access, with 80 percent of drugs available to them first, followed by Germany and the United Kingdom at 47 and 41 percent, respectively, and then Canada and Australia trailing at 26 percent and 19 percent, respectively.[37] For these medicines, the average delay in availability averaged 0 to 3 months from launch in the United States, 10 months in Germany, 11 in the United Kingdom, 15 in Canada, 16 in Japan, 18 in France, and 20 in Australia. These are hug differences.

The Pace of Development

Finally, to press the case for dismantling the U.S. drug development system, opponents argue that the system is not effectively performing its core function: producing effective treatments and cures. Given that the leading drug companies came up with COVID-19 vaccines in record time, using breakthrough technologies, this case is much harder to make now. But undeterred, the Porter report states, “Rather than producing breakthrough, lifesaving drugs for diseases with few or no cures, most companies focus on small, incremental changes to existing drugs in order to kill off generic threats to their government-granted monopoly patents.”[38]

But in reality, new drug approvals have significantly accelerated. The FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research’s five-year rolling approval average stood at 44 new drugs per year in 2019, double the five-year rolling average of 22 drugs approved, as happened in 2009. And the number of drugs in development globally increased from 5,995 in 2001 to 13,718 in 2016.[39] Moreover, the share of drugs that are new has risen since the 1970s, not fallen.[40]

At the end of the day, the America’s private sector-led drug development system, coupled with the support of university research and the National Institutes of Health, has made the United States the medicine chest of the world, responsible for more new drugs than any nation. As much as the drug populists would like us to think otherwise, the truth is the current system is not just working; it’s the envy of the world.

But Trump’s cuts to the National Institutes of Health, combined with steep drug price controls will inevitably lead to fewer new drugs, worse public health outcomes, and the loss of U.S. biopharma leadership to China. That reversal of fortune will not occur overnight, in part because of the heretofore strong U.S. life sciences innovation system. But it doesn’t take a weatherman to know which way the wind blows. Can you say, “China as the medicine cabinet of the world”?

About the Author

Dr. Robert D. Atkinson (@RobAtkinsonITIF) is the founder and president of ITIF. His books include Technology Fears and Scapegoats: 40 Myths About Privacy, Jobs, AI and Today’s Innovation Economy (Palgrave McMillian, 2024), Big Is Beautiful: Debunking the Myth of Small Business (MIT, 2018), Innovation Economics: The Race for Global Advantage (Yale, 2012), Supply-Side Follies: Why Conservative Economics Fails, Liberal Economics Falters, and Innovation Economics Is the Answer (Rowman Littlefield, 2007), and The Past and Future of America’s Economy: Long Waves of Innovation That Power Cycles of Growth (Edward Elgar, 2005). He holds a Ph.D. in city and regional planning from the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

About ITIF

The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) is an independent 501(c)(3) nonprofit, nonpartisan research and educational institute that has been recognized repeatedly as the world’s leading think tank for science and technology policy. Its mission is to formulate, evaluate, and promote policy solutions that accelerate innovation and boost productivity to spur growth, opportunity, and progress. For more information, visit itif.org/about.

Endnotes

[1]. The Center for American Progress (CAP), “The Senior Protection Plan: $385 Billion in Health Care Savings Without Harming Beneficiaries” (CAP Health Policy Team, November 2012), https://cdn.americanprogress.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/SeniorProtectionPlan-3.pdf.

[2]. Dean Baker, “Malpractice” (Center for Economic Policy Research (CEPR), May/June 2009), http://cepr.net/publications/op-eds-columns/malpractice.

[3]. James Love, “Groups, individuals write to Senator Wyden, appalled at pressure on India over drug patents,” Knowledge Ecology International, June 2017, https://www.keionline.org/?s=drug+patents.

[4]. Stephen Ezell, “Ensuring U.S. Biopharmaceutical Competitiveness” (ITIF, July 2020), https://itif.org/publications/2020/07/16/ensuring-us-biopharmaceutical-competitiveness/.

[5]. Office of Congresswoman Katie Porter, “Killer Profits: How Big Pharma Takeovers Destroy Innovation and Harm Patients” (January 2021), https://porter.house.gov/uploadedfiles/final_pharma_ma_and_innovation_report_january_2021.pdf.

[6]. Abbey Meller and Hauwa Ahmed, “How Big Pharma Reaps Profits While Hurting Everyday Americans,” (CAP Health Policy Team, August 2019), https://www.americanprogress.org/article/big-pharma-reaps-profits-hurting-everyday-americans/.

[7]. Bernie Sanders, “Greedy pharma firms rip off Americans while Pfizer, Moderna swim in profits,” (Bernie Sanders, January 2023), https://www.sanders.senate.gov/op-eds/greedy-pharma-firms-rip-off-americans-while-pfizer-moderna-swim-in-profits/.

[8]. “Trump says drug industry ‘getting away with murder,’ Politico, January 11, 2017, https://www.politico.com/story/2017/01/trump-press-conference-drug-industry-233475.

[9]. Neeraj Sood, Karen Mulligan, and Kimberly Zhong, “Do companies in the pharmaceutical supply chain earn excess returns?” International Journal of Health Economics and Management Vol. 21, No. 1 (2021), https://doi.org/10.1007/s10754-020-09291-1.

[10]. Neeraj Sood, Karen Mulligan, and Kimberly Zhong, “Do companies in the pharmaceutical supply chain earn excess returns?” International Journal of Health Economics and Management Vol. 21, No. 1 (2021), https://doi.org/10.1007/s10754-020-09291-1.

[11]. Ge Bai et al., “Profitability and risk-return comparison across health care industries, evidence from publicly traded companies 2010–2019,” PLoS ONE Vol. 17, Issue 11 (November 16, 2022), 1, https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0275245.

[12]. Rabah Kamal, Cynthia Cox Twitter, and Daniel McDermott, “What are the recent and forecasted trends in prescription drug spending?” (Peterson Center on Healthcare and Kaiser Family Foundation, February 20, 2019), https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/recent-forecasted-trends-prescription-drug-spending.

[13]. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, “Pharmaceutical spending as % total health spending, 2020 (or latest available year),” https://data.oecd.org/healthres/pharmaceutical-spending.htm.

[14]. S&P Biotechnology Select Industry Index (accessed August, 2023), https://www.spglobal.com/spdji/en/indices/equity/sp-biotechnology-select-industry-index/#overview; S&P Pharmaceuticals Select Industry Index (accessed August, 2023), https://www.spglobal.com/spdji/en/indices/equity/sp-pharmaceuticals-select-industry-index/#overview.

[15]. Altarum, “Projections of the Non-Retail Prescription Drug Share of National Health Expenditures,” September 2020, 3, https://altarum.org/publications/projections-non-retail-prescription-drug-share-national-health-expenditures.

[16]. Lisa M. Schwartz and Steven Woloshin, “Medical Marketing in the United States, 1997-2016” Journal of the American Medical Association Vol. 321, Issue 1 (2019): 80–96, DOI:10.1001/jama.2018.19320.

[17]. Beth Snyder Bulik “The top 10 ad spenders in Big Pharma for 2020,” Fierce Pharma, April 19, 2021, https://www.fiercepharma.com/special-report/top-10-ad-spenders-big-pharma-for-2020.

[18]. Ibid. p. 5

[19]. Scrip 100, (In Vivo Informa Pharma Intelligence, 2018), https://invivo.pharmaintelligence.informa.com/outlook.

[20]. Ibid.

[21]. Ibid

[22]. Ibid.

[23]. “Research and Development in the Pharmecutical Industry,” (Congressional Budget Office, April 2021) https://www.cbo.gov/publication/57126.

[24]. Juliette Cubanski and Tricia Neuman, “Prices Increased Faster Than Inflation For Half of all Drugs Covered by Medicare in 2020,” (KFF, February 2022) https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/prices-increased-faster-than-inflation-for-half-of-all-drugs-covered-by-medicare-in-2020/.

[25]. Benjamin Rome, Alexander Egilman, and Aaron Kesselheim, “Prices for New Drugs Are Rising 20 Percent a Year. Congress Needs to Act,” New York Times, June 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/08/opinion/us-drug-prices-congress.html.

[26]. Alan Goforth, “Time to revisit out-of-pocket expenses calculations? Consumers burn through their share in a matter of days,” ALM Benefits Pro, February 4, 2021, https://www.benefitspro.com/2021/02/04/time-to-revisit-out-of-pocket-expenses-calculations-consumers-burn-through-their-share-in-a-matter-of-days/.

[27]. Stephen Ezell, “Testimony to the Senate Finance Committee on ‘Prescription Drug Price Inflation’,” (ITIF, March 2022), https://itif.org/publications/2022/03/16/testimony-senate-finance-committee-prescription-drug-price-inflation/.

[28]. Andrew Brownlee and Joran Watson, “The Pharmaceutical Supply Chain, 2013-2020,” (Berkeley Research Group, 2022), 3, https://www.thinkbrg.com/insights/publications/pharmaceutical-supply-chain-2013-2020/.

[29]. Ibid.

[30]. Karen Van Nuys et al., “Estimation of the Share of Net Expenditures on Insulin Captured by US Manufacturers, Wholesalers, Pharmacy Benefit Managers, Pharmacies, and Health Plans From 2014 to 2018” Journal of the American Medical Association Vol. 2, Issue 11 (2021), https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama-health-forum/fullarticle/2785932.

[31]. Adam Fein, “Drug Channels News Roundup, March 2020: Sanofi’s Gross-to-Net Bubble, Drug Pricing Findings, Amazon Replaces Express Scripts, and Drug Channels Video,” Drug Channels, March 31, 2021, https://www.drugchannels.net/2020/03/drug-channels-news-roundup-march-2020.html.

[32]. “In Bipartisan Push, Hawley &. Welch Introduce Major Legislation to Lower Prescription Drug Prices,” Josh Hawley, U.S. Senator for Missouri, May 5, 2025, https://www.hawley.senate.gov/in-bipartisan-push-hawley-welch-introduce-major-legislation-to-lower-prescription-drug-prices/

[33]. Trelysa Long and Stephen Ezell, “The Hidden Toll of Drug Price Controls: Fewer New Treatments and Higher Medical Costs for the World” (ITIF, July 2023), https://itif.org/publications/2023/07/17/hidden-toll-of-drug-price-controls-fewer-new-treatments-higher-medical-costs-for-world/.

[34]. Academic studies consistently show that a reduction in current drug revenues leads to a fall in future research and the number of new drug discoveries.

[35]. Kevin Haninger, “New analysis shows that more medicines worldwide are available to U.S. patients,” The Catalyst, June 5, 2018, https://catalyst.phrma.org/new-analysis-shows-that-more-medicines-worldwide-are-available-to-u.s.-patients; Patricia M. Danzon and Michael F. Furukawa, “International Prices And Availability Of Pharmaceuticals In 2005” Health Affairs Vol. 7, No. 1 (January/February 2008), https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/abs/10.1377/hlthaff.27.1.221.

[36]. PhRMA analysis of IQVIA Analytics Link, U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), European Medicines Agency (EMA), Japan’s Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA), Health Canada and Australia’s Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) data. June 2020. Note: New active substances approved by FDA, EMA, PMDA, Health Canada and/or TGA and first launched in any country between January 1, 2011 and December 31, 2019.

[37]. Ibid.

[38]. https://itif.org/publications/2021/05/20/five-fatal-flaws-rep-katie-porters-indictment-us-drug-industry/.

[39]. In Vivo: The Business and Medicine Report, vol34, no. 1 (January 2016), 25, https://invivo.pharmaintelligence.informa.com/outlook/industry-data/-/media/marketing/Outlook%202019/pdfs/2016.PDF (subscription only).

[40]. Ibid.

Editors’ Recommendations

Related

December 11, 2023