South Korean Policy in the Trump and China Era: Broad-Based Technological Innovation, Not Just Export-Led Growth

In the Trump and China era, South Korea must move beyond export-led growth. Scaling up small firms and boosting productivity in services must be national imperatives.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Key Takeaways

Contents

Diagnosing South Korea’s Productivity Gap: The Two-Speed Economy 6

Why South Korea’s Model Is Stuck: Structural and Policy Barriers 17

South Korea Needs a New Economic Playbook. 26

Conclusion: Toward a Productivity-Led Growth Model 31

Introduction

For decades, South Korea stood at the center of global supply chains—a fast follower in industrial technology, developer of an agile manufacturing base, and a model of export-led growth. This strategy propelled the country from postwar poverty to industrial prominence, creating world-class champions in semiconductors, electronics, shipbuilding, and autos. It was a success story built on scale, capital intensity, and exports—and for many years, it worked.

But the world has changed. The Trump era marks a fundamental rupture in the rules of global commerce. The United States is shifting toward strategic protectionism, treating tariffs not as threats but as policy baselines. And China, once a market for South Korean exports, is becoming an increasingly aggressive and dominant rival. Global markets are fragmenting and competition for South Korea’s core sectors is rising—and South Korea, heavily reliant on high-tech exports, stands directly in the crosshairs. Simply exporting more, even cutting-edge goods is no longer enough.

At home, structural headwinds are compounding this challenge. South Korea’s growth model is still anchored in large-scale manufacturing, while much of the domestic nonmanufacturing economy remains highly underproductive. Despite ranking first globally in research and development (R&D) intensity, South Korea’s innovation system is overly concentrated in a few capital-intensive sectors. Services, small firms, and consumer-facing industries remain disconnected from this innovation pipeline. The result is a two-speed economy: world-class at the top, stagnant at the base.

The symptoms are clear:

▪ SMEs account for 99.9 percent of registered firms and 81 percent of employment, but their productivity remains less than half that of large firms in manufacturing—and less than 40 percent in services.[1]

▪ While manufacturing productivity grew 19 percent from 2013 to 2022, service-sector productivity rose only 6 percent, even though services now employ over 70 percent of South Korea’s workforce.[2]

▪ Due to this structural imbalance, high-quality jobs in large enterprises account for only 13.9 percent of total employment in South Korea, which is dramatically lower than the 57.6 percent found in the States.[3] The shortage of stable, well-paying jobs accelerates early retirement, pushes older workers into low-productivity self-employment, wastes the potential of highly educated youth in low-quality small and medium-sized enterprise (SME) jobs, and contributes to South Korea’s record-low fertility rate.

These gaps are not accidental. They are policy driven.

For too long, South Korea has prioritized firm survival over scale. More than 1,600 SME support programs, credit guarantees, and regulatory protections have encouraged fragmentation, discouraging consolidation, automation, and innovation diffusion. South Korea’s regulatory systems are wrongly biased toward small firms, and stability, rather than creative destruction. Overall, SME policy has emphasized survival, not growth—trapping small firms in low-productivity equilibrium.

At the same time, South Korea’s innovation strategy remains concentrated in capital-intensive, export-oriented sectors. More than 70 percent of R&D spending goes to a narrow band of manufacturing industries, with minimal technology diffusion to services, small firms, or consumer-facing sectors such as healthcare, logistics, retail, and agriculture. Digital adoption among firms, especially SMEs, remains low, especially for transformative tools such as Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) systems, cloud computing, and artificial intelligence (AI).

These structural weaknesses—particularly South Korea’s overreliance on small firms—are colliding with severe demographic headwinds: the fastest aging population in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the world’s lowest fertility rate, widespread education-to-employment mismatch among university graduates, and one of the earliest effective retirement ages. Put simply, South Korea is producing more retirees and college graduates than its economy can absorb—especially given the limited number of high-quality jobs in large enterprises. To sustain future growth, the productivity of SMEs must rise dramatically, approaching the standards of large firms.

This is the challenge of South Korea’s next economic chapter: to shift from a fragmented, export-heavy model to a broad-based, productivity-led growth strategy—anchored in innovation diffusion, SME scale-up, and sector-wide digital transformation.

South Korea is producing more retirees and college graduates than its economy can absorb—especially given the limited number of high-quality jobs in large enterprises. To sustain future growth, the productivity of SMEs must rise dramatically, approaching the standards of large firms.

The Road Ahead: A National Productivity Reset

South Korea cannot navigate the new era of economic nationalism with an outdated playbook. The old model—centered on exports, chaebol dominance, and survival-based SME policy—is no longer fit for purpose. What’s needed is a full-spectrum reset: from fragmented growth to economy-wide innovation diffusion; from firm preservation to performance-driven scale; from educational attainment to high-quality employment.

This report outlines a next-generation productivity strategy built on the following four pillars:

1. Move beyond protectionist, survival-focused SME policy and toward growth-oriented frameworks that reward scale, productivity, and innovation. Level the playing field by eliminating institutional biases that keep firms small and unproductive. South Korea must adopt size-neutral policies that incentivize growth rather than fragmentation.

2. SME support should be tied to measurable improvements in productivity and scales, such as the adoption of data analytics solutions, while phasing out regulatory protections that shield inefficiency.

3. Diffuse innovation across all sectors, not just the export elite. South Korea’s next productivity surge will come not from chip fabs alone but also from bringing modern tools—AI, cloud, automation—to lagging service sectors such as logistics, construction, and agriculture. That means launching a national digital transformation program tailored to these industries, backed by bundled tech subsidies and last-mile delivery mechanisms.

4. Rebuild the labor market around mobility, not rigidity. South Korea must expand its footprint of mid- and large-sized enterprises to generate more high-quality jobs—and create new transition frameworks that allow workers to move, reskill, and reenter. This includes designing flexible labor standards, reemployment safety nets, modular higher education, and globally competitive talent systems.

Specifically, South Korea policy makers should take the following steps:

▪ Eliminate the National Commission for Corporate Partnership (KCCP) and the Livelihood-Supporting Industry designation.

▪ Craft a new charter for the Korean Fair Trade Commission (KFTC) to eliminate explicit or implicit mandates that prioritize the protection of small firms as a class.

▪ The KFTC should withdraw its push for both the Platform Competition Promotion Act (PCPA) and the Partial Amendment Bill (PAB).

▪ Reconstitute the Ministry of SMEs and Startups (MSS) into a new Ministry of Enterprise Growth.

▪ Eliminate size-based tax distortions.

▪ Redirect SME support to drive productivity gains.

▪ Launch a graduation accelerator fund.

▪ Establish a microbusiness exit and reallocation fund.

▪ South Korea’s science and technology agencies develop sector-specific strategies to boost productivity in lagging areas through tailored digital tools.

▪ Accelerate technology adoption in low-productivity sectors.

▪ Expand technology tax credits to all firms—regardless of size or sector—that adopt ERP, AI, or robotics.

▪ Establish a productivity-centered labor framework.

▪ Modernize infrastructure for innovation diffusion.

▪ Build a national productivity dashboard to track sectoral output gains and digital adoption in real time.

▪ Replace South Korea’s permission-based regulatory system with a negative-list approach that enables innovation by default.

▪ Expand the share of high-quality jobs by growing large enterprises.

▪ Build a “Closure-to-Reemployment” safety net.

▪ Design a flexible and fair labor framework.

▪ Transform universities into lifelong learning institutions.

▪ Create a global talent mobility package.

South Korea’s next economic chapter won’t be written in port terminals. It will be written in algorithms, Application Programming Interfaces (APIs), and productivity gains across the entire economy. The Trump 2.0 era is not just a risk; it is a structural test—and an opportunity to reset South Korea’s growth model for a world in which innovation is survival.

Diagnosing South Korea’s Productivity Gap: The Two-Speed Economy

After decades of rapid growth led by large, industrialized chaebol firms, South Korea has reached the technology frontier in many of its flagship manufacturing industries. But this success masks a deeper, structural problem: the emergence of a “two-speed economy” wherein gains made by large, export-oriented manufacturers are slowing and still not matched by the broader domestic economy, especially in services and small businesses generally.

To sustain long-term growth in the Trump 2.0 era, South Korea must confront the internal imbalances that now constrain its economy. The following sections examine four key dimensions of this productivity divide: the firm-size gap, the manufacturing–services divide, the innovation mismatch, and labor market constraints.

Large Corporations vs. SMEs: Scale, Structure, and Survival

The South Korean economy is severely out of balance, with far too many low-productivity SMEs, which account for 99.9 percent of all registered firms and employ 81 percent of the workforce.[4] Over the past decade, most advanced economies have seen a notable increase in the employment share of large firms. In contrast, South Korea has experienced a rising concentration of employment in small enterprises. According to the 2020 Economic Census, 65.5 percent of all workers in South Korea were employed by firms with fewer than 50 employees, the highest proportion among 31 OECD countries.[5]

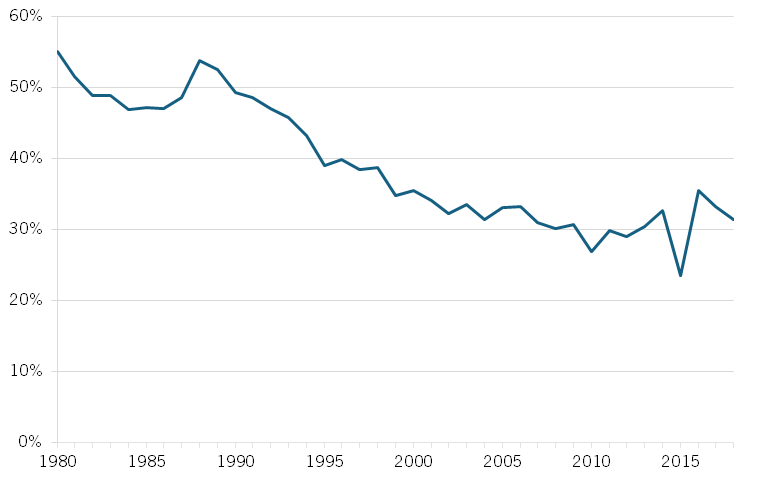

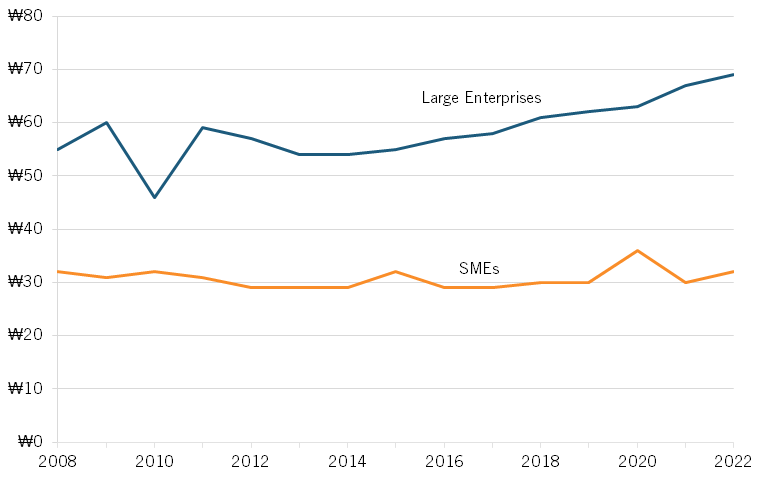

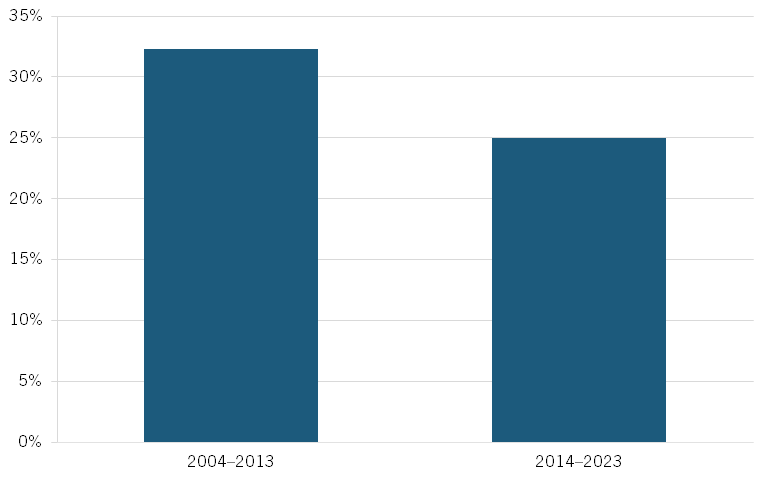

Yet, despite their structural dominance, South Korean SMEs remain chronically underproductive, especially when compared with large firms (figure 1). The result is a dual economy: world-class export champions on one end and a long tail of low-productivity firms on the other.

Figure 1: Value added per employee in SMEs relative to large firms[6]

The employment share of SMEs in South Korean is the highest in OECD, and SME productivity is only about one third of that of large companies, compared with around half in other OECD countries. And while large firms consistently outperform SMEs in labor productivity, and the gap is continuing to widen over time (figure 1).

Most advanced economies have seen a notable increase in the employment share of large firms, while South Korea has experienced a rising concentration of employment in small enterprises.

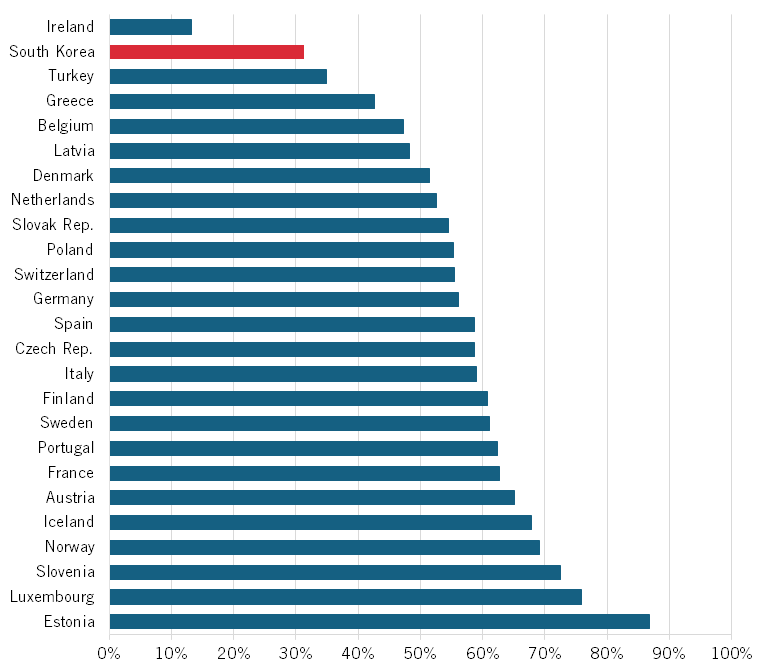

Figure 2: Value added per employee in OECD SMEs relative to large firms, 2020

In South Korea’s manufacturing sector, labor productivity among SMEs typically reaches less than 50 percent of that of large firms, with sector-specific ratios frequently falling below 40 percent. This productivity gap is significantly wider than in most other advanced economies.

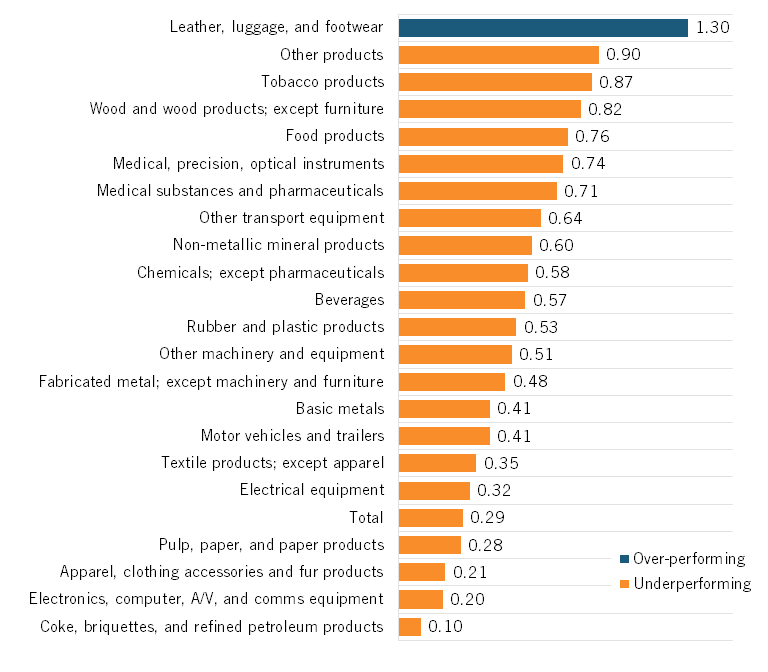

Notably, in high-value sectors such as electronics, chemicals, and machinery—industries that serve as foundational pillars of South Korea’s industrial ecosystem—SMEs consistently underperform relative to their larger counterparts, despite accounting for a substantial share of total employment. In figure 3, a value greater than 1 indicates SMEs are as productive or more productive than large enterprises in that industry. Values than 1 indicate SMEs are less productive than large enterprises in that industry. Gap is even wider than in manufacturing across most subsectors.

Figure 3: Manufacturing labor productivity in SMEs relative to large enterprises[7]

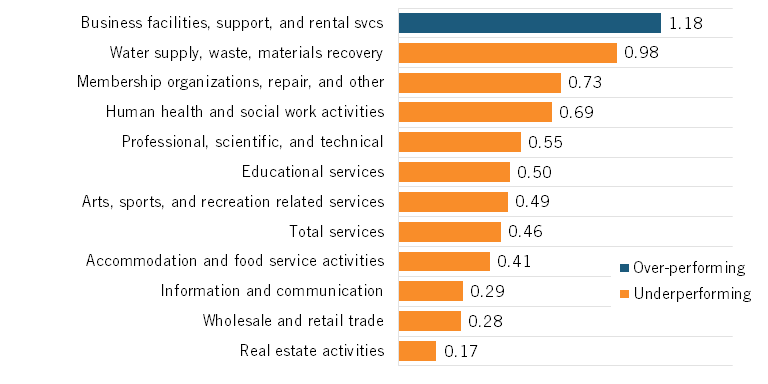

In services (figure 4), the productivity gap is even more pronounced. Between 2013 and 2023, productivity among large service firms grew by 21 percent, while SME productivity in the same sector declined by 3 percent. Service-sector SMEs operate at less than 50 percent of the productivity of large firms. This productivity gap is particularly severe in real estate activities, accommodation, and retail—sectors that are employment heavy but innovation light. This divergence reflects structural differences in scale, digital adoption, and investment capacity between large enterprises and SMEs.

Figure 4: Service labor productivity in SMEs relative to large enterprises[8]

The productivity gap is particularly severe in real estate activities, accommodation, and retail—sectors that are employment heavy but innovation light. This divergence reflects structural differences in scale, digital adoption, and investment capacity between large enterprises and SMEs.

Manufacturing vs. Services: A Widening Divide

South Korea’s global economic reputation is anchored in its success as a manufacturing giant. Semiconductors, automobiles, and steel have long defined the country’s export competitiveness; however, this sectoral strength obscures a fundamental imbalance.

While manufacturing continues to drive productivity, South Korea’s services sector—responsible for 62.3 percent of total value added and 71.2 percent of employment in 2023—remains a persistent productivity weak spot.[9]

Labor productivity in manufacturing grew by 19 percent between 2013 and 2022, while services increased by only 6 percent over the same period. This already significant gap continues to widen. While the manufacturing productivity growth rate is relatively low, especially compared with South Korean history, the service sector growth rate remains anemic.

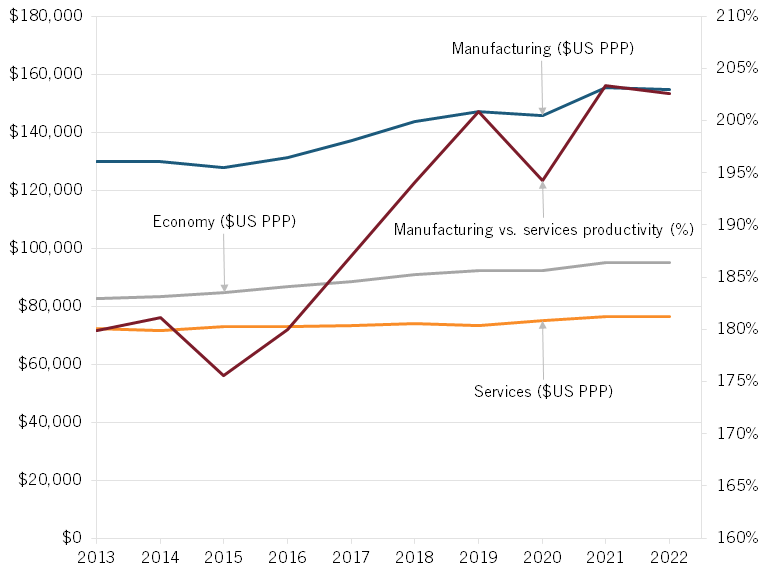

Productivity growth in South Korea’s manufacturing sector has consistently outpaced that of services by a factor of three to one (figure 5). This divergence is evident not only in growth rates but also in absolute productivity levels. In 2022, labor productivity in manufacturing reached $154,555 in U.S. purchasing power parity (PPP) per worker, compared with $76,280 PPP per worker in the services sector. In other words, manufacturing workers produce more than twice as much value as do their counterparts in services—a productivity gap of 103 percent. The persistent underperformance of the services sector remains a critical structural challenge for South Korea’s broader economic competitiveness.

Figure 5: Manufacturing vs. services productivity per employed person ($US PPP per worker)[10]

Productivity growth in South Korea’s manufacturing sector has consistently outpaced that of services by a factor of three to one. This divergence is evident not only in growth rates but also in absolute productivity levels.

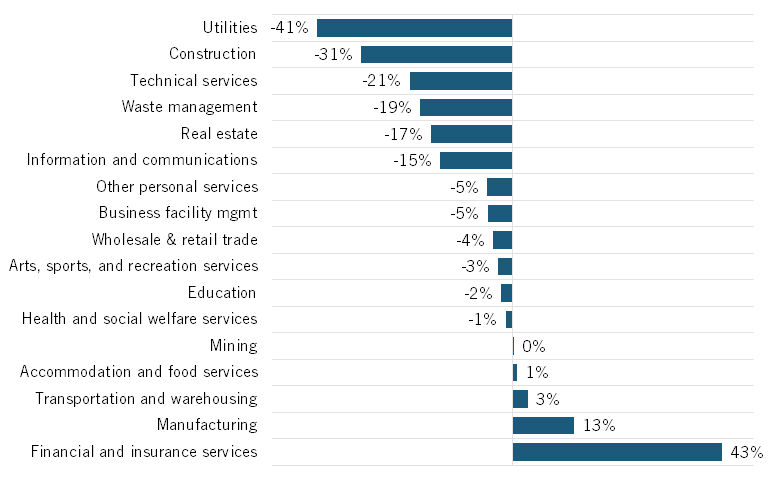

The productivity ratio of manufacturing to services has exceeded 200 percent in recent years. An industry-level breakdown reveals the systemic nature of this challenge (figure 6). Between 2013 and 2023, several foundational service sectors saw significant productivity declines: utilities at -41 percent, construction at -31 percent, technical services at -21 percent, waste management at -19 percent, real estate at -17 percent, and information communications at -15 percent. This flat or negative productivity performance is also evident in key social and consumer services.

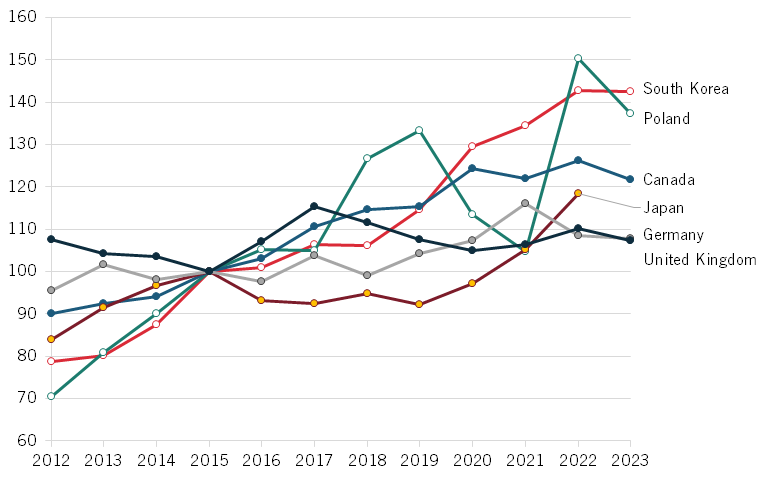

OECD data further underscores these patterns. South Korea’s productivity in agriculture, forestry, and fishing (figure 7) consistently ranks among the lowest across major OECD economies and has actually declined since 2015.

Figure 6: Productivity change by industry, 2013–2023[11]

Figure 7: Agriculture, forestry, and fishing productivity (gross value added per person, index, 2015 = 100)[12]

In contrast, finance and insurance services report productivity levels that are broadly in line with the OECD median (figure 8). These gaps mirror the broader technology divide between large enterprises and SMEs observed across sectors, with higher productivity typically associated with greater digital adoption and scale.

Figure 8: Finance and insurance productivity (gross value added per person, 2015 = 100)[13]

Notably, sectors with the weakest productivity—such as agriculture, construction, and real estate—tend to be labor-intensive and critical to infrastructure and housing. Their stagnation reflects chronic underinvestment in process innovation, limited adoption of automation, and persistent industry firm fragmentation.

The decline in ICT-related services productivity (-15 percent) is particularly striking, given South Korea’s reputation for broadband penetration and 5G infrastructure. This suggests that South Korea’s digital economy remains heavily hardware centric, with weak productivity growth and adoption at the software and service layers.[14]

Meanwhile, other high-employment but low-productivity sectors have remained stagnant: business facility mgmt. at -5 percent, other personal services at -5 percent, wholesale & retail trade at -4 percent, education at -2 percent, health & social welfare at -1 percent.

These sectors are often public or semi-informal, with limited performance incentives, low adoption of digital tools, and little scope for consolidation or automation.

Figure 9: Services labor productivity (KRW millions)[15]

Figure 10: South Korean services productivity growth[16]

South Korea’s manufacturing sector continues to serve as the anchor of its economic model. Over the last decade, manufacturing saw steady productivity gains (+13 percent), with particular strength in information and communications technology (ICT) hardware, automotive, and advanced materials. This confirms South Korea’s comparative advantage in high-capital, export-driven industrial production.

However, manufacturing’s share of employment continues to shrink. According to Statistics Korea’s Employment Trends, March 2025, the share of employment in manufacturing fell to 15.39 percent of total employment (28.59 million workers), down from 15.89 percent a year earlier.[17] This represents the lowest level since comparable data collection began in 2013 when the manufacturing employment share was 17.23 percent. The decline reflects a continuing structural shift in South Korea’s labor market toward services and automation-driven productivity in manufacturing.

Without productivity gains in services, overall national productivity will stagnate.

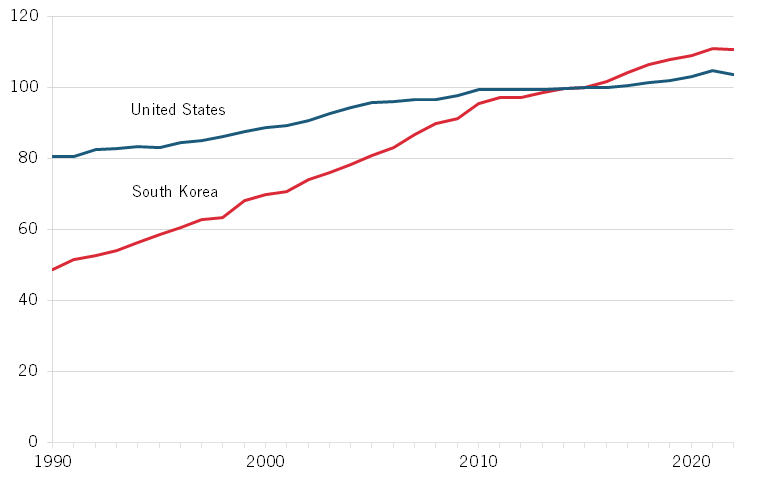

Despite South Korea’s high investment, U.S. firms achieve more output per unit of input due to stronger innovation diffusion.

Without productivity gains in services, overall national productivity will stagnate.

Figure 11: Multifactor productivity (index, 2015 = 100)[18]

SME & Services Are Too Big to Fail—But Too Small in Productivity

The problem is not just low service productivity; it’s also the fact that services now employ the majority of the population. The services sector not only lags behind in performance, but it also dominates the economy in terms of jobs.

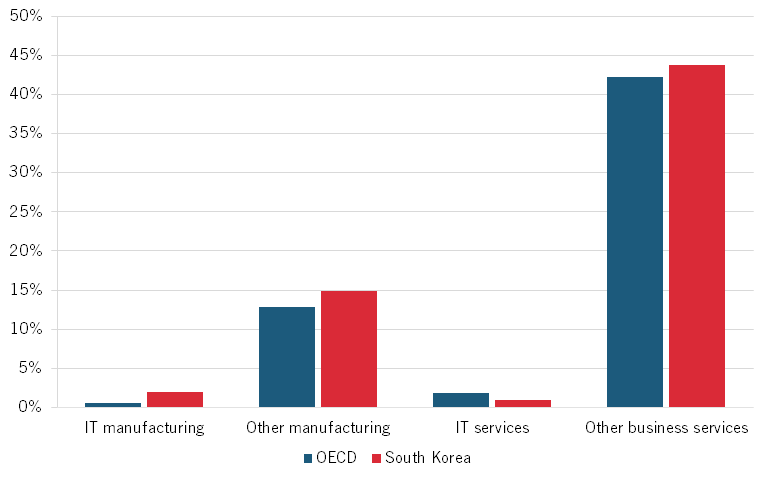

Figure 12: Sectors’ share of employment[19]

Services employment is high, while the sector’s productivity is low. Low-productivity sectors—such as wholesale and retail trade, transportation, accommodation, and food services—account for a larger share of total employment in South Korea (28 percent) than the OECD average (25 percent).

A significant portion of job creation within South Korea’s SMEs also occurs in these low-productivity sectors.[20] In 2017, 56 percent of jobs generated by new SME formation were concentrated in trade, transportation, accommodation, and food services, mirroring trends observed across many OECD economies.[21]

Even within high-productivity sectors such as manufacturing, SMEs account for a large share of both enterprises and employment—but their productivity remains substantially lower than that of large manufacturers. While the productivity gap between SMEs and large enterprises is a common feature across OECD countries, it is noticeably wider in South Korea.[22] This gap underscores the challenges South Korea faces in fostering productivity growth across its SME sector, particularly in industries that are critical to industrial competitiveness.

SMEs and the service sector continue to drag down South Korea’s overall productivity—and manufacturing is not immune.

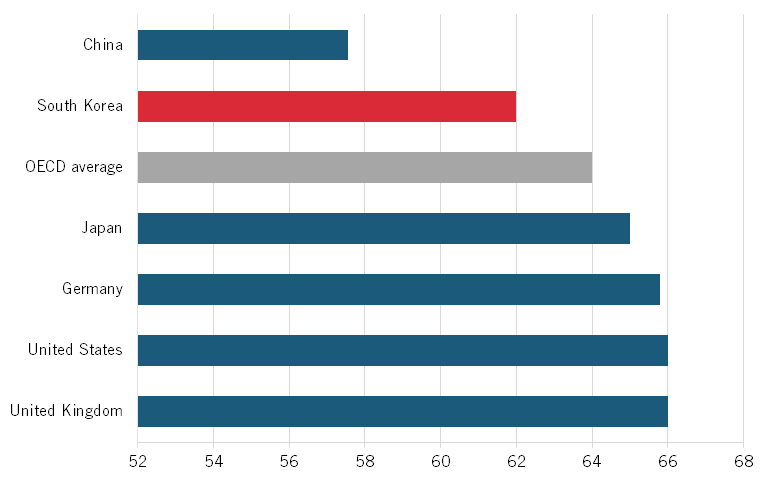

Labor Market Outcomes and Societal Consequences

Even if South Korea successfully addresses firm- and sector-level inefficiencies, deeper structural challenges remain embedded within the labor market. South Korea’s highly imbalanced industrial structure—characterized by the dominance of SMEs and the limited scale of its large enterprise sector—continues to constrain the creation of high-quality jobs. According to a report by the Korea Development Institute (KDI), only 13.9 percent of South Korean jobs were in large enterprises as of 2021, the lowest share among 32 OECD countries, and less than half the OECD average of 32.2 percent. By comparison, 57.6 percent of U.S. jobs are in large firms, followed by 41.1 percent in Germany and 40.9 percent in Japan.[23]

The shortage of stable, well-paying jobs accelerates early retirement, pushes older workers into low-productivity self-employment, wastes the potential of highly educated youth in low-quality SME jobs, and contributes to South Korea’s record-low fertility rate.

This matters because employment in large firms is closely associated with superior labor conditions: higher wages, greater job stability, and broader access to benefits.[24] In 2023, workers in micro-enterprises (5–9 employees) earned just 54 percent of the wages paid to those in large firms (300 or more employees).[25] Even workers in mid-sized firms (100–299 employees) earned just 71 percent as much. Similar disparities exist in access to parental leave and other work-life balance benefits. A 2023 government survey finds that 95.1 percent of employees at large firms reported full access to parental leave, compared with 88.4 percent in mid-sized firms and just 71.9 percent in small firms.[26]

These labor market imbalances are not merely economic; they carry significant demographic and societal consequences. The shortage of stable, well-paying jobs accelerates early retirement, pushes older workers into low-productivity self-employment, wastes the potential of highly educated youth in low-quality SME jobs, and contributes to South Korea’s record-low fertility rate.

OECD data confirms that South Korea has one of the earliest effective retirement ages among advanced economies, something that the country can no longer afford given its demographic crisis (figure 13). At the same time, its fertility rate remains the lowest in the world, a dynamic partly driven by the lack of secure, family-friendly employment—especially for younger workers in their prime childbearing years.

South Korea exhibits one of the weakest alignments between educational attainment and job quality in OECD, despite having one of the highest tertiary education rates—nearly 70 percent of adults ages 25–34 hold a university degree. [28] According to OECD, 31 percent of degree holders report being overqualified for their current jobs. The underemployment rate—graduates working in roles that do not require a university education—exceeded 49 percent in 2019, more than double the OECD average of 23 percent. [29]South Korea is also the only OECD country where there is virtually no correlation between the field of study and occupational placement, indicating an absence of labor market payoff from academic specialization. These outcomes reflect a deeper structural dysfunction: a labor market that underutilizes talent, mismatches skills, and squanders years of public and private investment in higher education.

South Korea’s SMEs face a “triple trap”: they dominate employment but suffer from low productivity and weak digital integration. This “two-speed” economy is unsustainable for long-term growth, particularly amid heightened geopolitical uncertainty. Closing this divide is not only an economic priority, it is also a national imperative.

Why South Korea’s Model Is Stuck: Structural and Policy Barriers

South Korea’s remarkable ascent to industrial power has been driven by a focused, export-led strategy centered on large manufacturing firms and a goal of moving up the value chain. However, this success has made it easy for policymakers and thought leaders to paper over deep structural imbalances. These imbalances are not merely market outcomes; they are the result of deliberate institutional choices. The country’s current policy architecture reinforces the dual economy at the top, while regulatory and financial ecosystems inhibit transformation among the rest.

This section analyzes two central barriers: (1) an excessive and fragmented SME ecosystem locking the nation into a low-productivity trap and (2) a national innovation strategy that fails to spur broad-based innovation.

Policy Architecture That Rewards Staying Small and Inefficient

SMEs account for 99.9 percent of South Korean businesses and 81 percent of employment. While many look at this is a positive sign, the reality is that it is neither healthy nor the result of market forces alone.

Indeed, Article 123, Clause 3 of the Constitution of the Republic of South Korea states, “The State shall foster and protect small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).”[30] However, SME policy to date has focused more on protection than on fostering. This architecture has failed to deliver productivity gains or graduation from small to mid-sized status, entrenching small inefficient, low-wage firms that do not merit protection from market forces.

Instead of enabling scale and competitiveness, the system has locked in inefficiency—allowing underproductive microbusinesses to survive indefinitely without either growing or exiting. South Korea’s corporate lending heavily favors small firms regardless of performance, while public loan guarantees further insulate these firms from market discipline. One study of SME programs between 2003 and 2009 found that such policies had no measurable impact on profitability and in some cases even reduced sales growth.[31]

SMEs account for 99.9 percent of South Korean businesses and 81 percent of employment. While many look at this is a positive sign, the reality is that it is neither healthy nor the result of market forces alone.

Support Is Often Redundant Across Ministries and Excessive

The structural weakness of SMEs is not incidental—it is policy induced. South Korean SME policy has long prioritized survival over scaling, with broad protection and subsidies aimed at keeping firms afloat rather than enhancing performance. The reality is that if South Korea is to escape its economic malaise, it will need to not only accept but also embrace creative destruction that rebalances the economy away from so much activity in small firms.

▪ Over 1,600 SME-specific programs are run across ministries and levels.[32]

▪ South Korea operates a mandatory SME lending quota system, requiring commercial banks to allocate at least 45 percent of their loan increases to SMEs (60 percent for regional banks, 35 percent for certain others).[33]

▪ Credit guarantees and tax benefits are widespread but rarely tied to productivity outcomes.

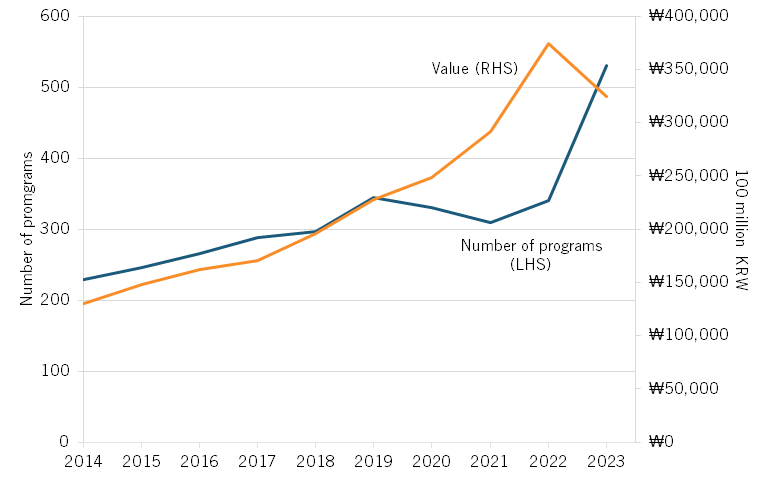

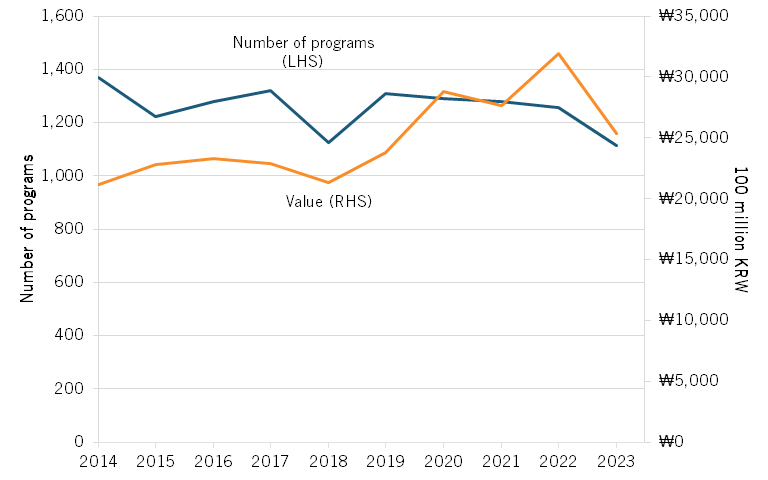

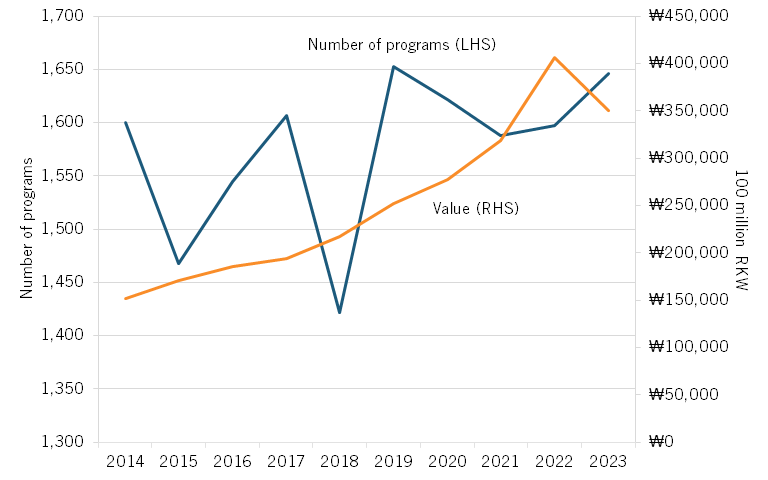

Figure 14: Central government programs to support SMEs[34]

Figure 15: Regional government programs to support SMEs[35]

Figure 16: Total programs supporting SMEs[36]

Between 2014 and 2023, the number of SME programs grew significantly—rising to 530 at the central level and 1,116 at the regional level—with combined annual spending exceeding ₩350 billion in recent years.

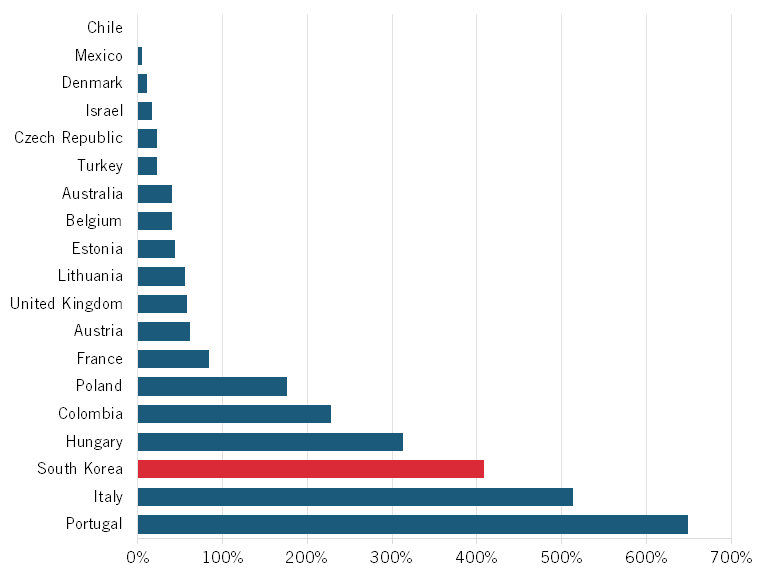

Figure 17: Government-guaranteed loans to SME, 2021 (percentage of GDP)[37]

Loan guarantees have also expanded steadily, further insulating firms from market-based discipline and not allowing “zombie” firms to die.

Regulations That Protect Small Firms From Market Forces

Regulatory agencies and regulations work to reinforce market protections for a small-firm economy.

First, the “SME-Suitable Industry” designation system (중소기업 적합업종 제도), implemented under the 2011 Act on the Promotion of Collaborative Cooperation between Large Enterprises and SMEs (상생협력법), restricts large firms from entering or expanding in industries deemed appropriate for small enterprises.[38] These include service-heavy, livelihood-related sectors such as bakeries, coin laundromats, and after-school tutoring. The designation leads to limitations on new store openings or regional market entry by large companies, lasts for three years, and can be extended through mutual agreement.

Second, the “Livelihood-Supporting Industry Protection System” (생계형 적합업종 제도), enacted in 2018, provides even stricter protections for micro-enterprises and traditional small merchants. In designated sectors—such as tofu, fermented sauce and bakery manufacturing, and book stores—large firms are effectively barred from entry, acquisition, or expansion for a minimum of five years.[39]

These systems were introduced to preserve competition and support vulnerable sectors—but have since created disincentives for growth:

▪ Firms stay small to retain access to benefits.

▪ Consolidation and scale-up are discouraged.

▪ Inefficiencies are preserved, not corrected.

Rather than narrowing the divide, government support policies have frequently entrenched it. Instances of firms graduating from SME status remain exceedingly rare. Between 2002 and 2012, only 696 firms transitioned out of SME status.[40] More recent data indicates that this trend persists, with only 96 firms advancing to middle-market enterprise (MME) status by 2018, and 89 of them reverting to SME status due to declining sales. Since 2014, a mere five firms have progressed from MME to large enterprise status.[41] The overwhelming majority remain small, fragmented, and dependent on public support—what some scholars call “policy-induced stagnation.”

Regulatory agencies and regulations work to reinforce market protections for a small-firm economy.

At the same time, the KFTC, unlike most of its OECD counterparts, prioritizes the protection and promotion of SMEs as a policy orientation embedded in its operational mandate, policy initiatives, and enforcement practices. Beyond its core role in competition enforcement, which can be biased against firms for the sin of being large, the KFTC administers a range of regulatory frameworks that institutionalize support for SMEs and reinforce their role in South Korea’s economic structure. One of the key statutes enforced by the KFTC is the Act on Fair Transactions in Subcontracting, which aims to establish fair trade practices between large enterprises and their SME subcontractors.[42] The act seeks to “correct unfair transactional practices of large enterprises in the course of transactions between large enterprises and small and medium enterprises and protect small and medium enterprises that are in a financially weaker position.”[43] In addition, Article 25 provides the KFTC with powers to regulate issues such as delayed payments, coercive transactions, and the misappropriation of proprietary information. The KFTC can intervene directly, investigate unfair practices, and impose corrective orders or administrative penalties. Some of the legal protections for SMEs stem from the Act on the Promotion of Collaborative Cooperation between Large Enterprises and SMEs, which states, “The purpose of this Act is to sharpen the competitiveness of large enterprises and small and medium enterprises by consolidating mutually beneficial cooperation between them and to attain their shared growth by resolving the polarization between large enterprises and small and medium enterprises with the aim of laying the foundation for sustainable growth of the national economy.”[44]

Furthermore, the KFTC’s pursuit of the PCPA (a proposed ex ante regulatory framework targeting designated large digital platforms) and the PAB to the Monopoly Regulation and Fair Trade Act (MRFTA) (an ex-post enforcement tool expanding the abuse of superior bargaining position doctrine) reflects a deliberate effort to expand its institutional mandate in digital markets, with a strong emphasis on protecting smaller market participants.[45] While differing in procedural design, both proposals include overlapping substantive obligations on large platforms, such as bans on self-preferencing, restrictions on tying, and enhanced data separation provisions that closely parallel the European Union’s Digital Markets Act.[46] The alignment across both legislative tracks suggests that South Korea, through the KFTC, is not merely modernizing competition law but also embedding SME protection as a structural principle within platform regulation. The cumulative effect of this dual-track approach—combining ex ante controls with broadened ex post remedies—places South Korea among the jurisdictions seeking to reconfigure digital competition policy around platform accountability, but with a distinctively actor-centric orientation rooted in longstanding pro-small-business priorities.

Unlike most of its OECD counterparts, the Korean Fair Trade Commission prioritizes the protection and promotion of SMEs as a policy orientation embedded in its operational mandate, policy initiatives, and enforcement practices.

Finally, the KFTC’s enforcement practices further illustrate its commitment to protecting smaller market participants, particularly in the digital economy. For example, in June 2024, the KFTC fined Coupang over 140 billion KRW and issued a corrective order for allegedly manipulating search algorithms to favor its private-label products over third-party sellers.[47] The commission is also investigating Google’s alleged bundling of YouTube Music with paid YouTube subscriptions, amid concerns about foreign platform dominance and declining market share for domestic services. These actions are taking place alongside the KFTC’s policy initiatives (i.e., the push for the previously mentioned PCPA or the PAB).[48]

While these systems were introduced with the intention to limit chaebol dominance, they limit scale, discourage innovation, and reduce the incentive for productivity-enhancing competition. By locking firms into protected low-margin sectors, these frameworks reinforce fragmentation and slow transformation. Moreover, the idea that massive numbers of small companies enable competition is simply wrong. The opposite of monopoly is not massive fragmentation and concentration ratios of 1.[49]

Additional institutional features further reinforce this dynamic. South Korea’s policy framework often unintentionally incentivizes self-employed individuals to remain in low-productivity, survival-mode businesses rather than scale up or formalize. These institutional rigidities make it rational for many entrepreneurs to prioritize stability over growth. Key factors include:

▪ size-based eligibility for tax relief and subsidies;[50]

▪ labor law thresholds that exempt businesses with fewer than five employees from core provisions of the Labor Standards Act;[51]

▪ the simplified value-added tax (VAT) regime, which increases tax and administrative obligations when revenue surpasses 104 million KRW;[52] and

▪ public training programs that focus heavily on traditional, low-margin services rather than high-growth potential sectors.[53]

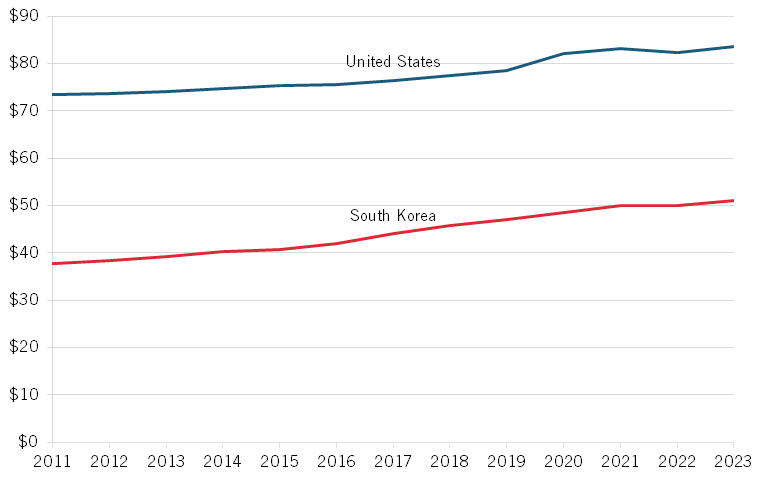

These policies do not just shape firm behavior—they have national implications. South Korea’s SME inefficiencies drag down overall productivity, including that of large firms embedded in the same ecosystems. In OECD benchmarking, South Korea trails the United States by 20–30 percent in labor productivity across most major sectors. And this raises costs for large and mid-sized exporting firms, making them less competitive in global markets.

Figure 18: South Korea vs. United States labor productivity (GDP per hour worked, PPP, 2020 prices)[54]

In short, South Korea’s productivity challenge is not a lack of innovation and scale—it is a lack of diffusion. The country’s digital and innovation ecosystem is hierarchical and closed. Services and SMEs remain disconnected from the R&D pipeline, locked into survival-mode structures.

The idea that massive numbers of small companies enable competition is simply wrong. The opposite of monopoly is not massive fragmentation and concentration ratios of 1.

South Korean SMEs Often Lack Technological Capabilities

A Legacy of Low-Value Entrepreneurship and Talent Gaps in High-Tech Services

One of the core obstacles to scaling SMEs in South Korea stems from the underlying composition of its industrial and entrepreneurial ecosystem. A disproportionately high share of business creation is concentrated in low-value-added service sectors—primarily retail, food, and accommodation—driven largely by necessity-based self-employment. As of 2020, self-employed workers accounted for 21.3 percent of South Korea’s total employment, ranking 6th among 37 OECD countries.[55] However, the vast majority of these businesses fall under subsistence entrepreneurship, with limited potential for growth or innovation.

In 2021, only 16.9 percent of newly established firms were in technology-based industries such as information and communications or professional, scientific, and technical services—sectors known to generate broader economic spillovers. In contrast, 83.1 percent of new businesses were in non-technology-based sectors.

This imbalance is compounded by a chronic shortage of R&D talent in high-value, knowledge-intensive services. In 2019, just 26.7 percent of full-time R&D personnel in South Korea’s service sector were employed in professional, scientific, and technical services—placing South Korea 23rd among 29 OECD countries.

South Korea must address the oversupply of low-productivity service businesses and foster conditions that enable self-employed individuals to transition into sustainable, growth-oriented enterprises. Yet, historically, government policy toward the self-employed has focused more on protection than on strengthening their long-term competitiveness or resilience.

Hardware-Rich, Software-Poor

Firm size is a substantially stronger determinant of adoption for data-intensive technologies and enterprise software solutions than for Internet of Things (IoT) technologies or cloud computing. According to Statistics Korea’s Statistical Research Institute, the adoption rate of emerging technologies in South Korea shows significant disparities by firm size. Among large enterprises with 300 or more employees, 24.5 percent have adopted at least one advanced technology, compared with just 12.1 percent of medium-sized firms (50–299 employees).[56] The gap is particularly pronounced for AI, with an adoption rate of 9.2 percent among large firms versus only 2.9 percent among medium-sized firms—more than a threefold difference. A similar pattern holds for industrial robotics (4.7 percent for large firms versus 1.2 percent for medium-sized firms). Across the SME segment, adoption rates for key digital technologies remain in the single digits: cloud computing at 6.3 percent, big data analytics at 5.3 percent, and AI at 4.0 percent.

The services sector, wherein most South Korean jobs are concentrated, remains labor intensive, under-digitized, and highly informal.[57] More than 20 percent of the workforce is self-employed, often in low-value-added activities.

The gap is particularly pronounced for AI, with an adoption rate of 9.2 percent among large firms versus only 2.9 percent among medium-sized firms—more than a threefold difference.

As of 2022, self-employed workers accounted for 23.5 percent of South Korea’s total employment—dramatically higher than in advanced economies such as the United States (6.28 percent), Canada (7.24 percent), Germany (8.75 percent), and Japan (9.6 percent). While this may appear to reflect a robust entrepreneurial spirit on the surface, it is in fact a byproduct of deep structural issues: labor market rigidity, weak reemployment pathways, and insufficient social safety nets. In the absence of sufficient high-quality jobs, self-employment often serves as a last-resort livelihood strategy. Yet, this pattern significantly undermines national productivity, economic efficiency, and long-term resilience.[58]

While over 55 percent of large firms adopt cloud-based technologies, fewer than 10 percent of SMEs do. Adoption of AI, machine learning, or even basic analytics remains negligible. E-commerce capacity also lags behind OECD peers.

These domestic patterns are broadly consistent with international comparisons reported by OECD, which also highlight significant adoption gaps between SMEs and large enterprises across advanced economies.

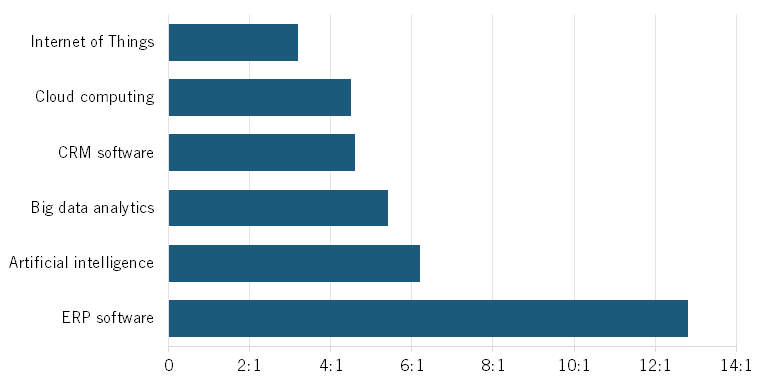

Figure 19: Average odds of adopting advanced software or data-intensive technologies in large enterprises vs. small enterprises, 2013–2023[59]

Note: Odds ratios reflect OECD data comparing firms with 250+ employees vs. firms with 10–49 employees.

Self-employed workers accounted for 23.5 percent of South Korea’s employment—dramatically higher than in advanced economies such as the United States (6.28 percent), Canada (7.24 percent), Germany (8.75 percent), and Japan (9.6 percent). This pattern significantly undermines productivity.

As illustrated in figure 19, large enterprises are three to seven times more likely than SMEs to adopt systems such as enterprise resource planning AI and big data analytics—technologies that typically require greater organizational scale, technical capacity, and investment in complementary assets. In South Korea, the gap between large and small firms is consistent with the OECD average—but SME adoption rates remain among the lowest across OECD countries, particularly in cloud computing and data analytics. In contrast, adoption gaps for Internet of Things and cloud computing are comparatively narrower, reflecting their lower barriers to entry and broader applicability across firm sizes.

This digital lag is not solely a matter of infrastructure or technical capacity. According to KDI studies, SMEs in South Korea face a range of systemic barriers, including limited access to digital skills, underdeveloped support systems, and a fragmented ecosystem for SME-oriented software and digital solutions.[60] While broadband access is near universal, most small firms lack the advisory, integration, and scaling tools necessary to make digital transformation viable.

South Korea Needs a New Economic Playbook

For decades, South Korea’s growth model was built on scale manufacturing, fast technology adoption, and export-led integration into global markets. This “fast follower” strategy worked spectacularly well in an era of open markets and stable globalization. But that world is over. The global trade and technology environment is now being reshaped by two structural forces: the rise of Chinese technology leadership and protectionist American trade policy.

Why the Old Playbook No Longer Works

“The model worked—until it didn’t.”

U.S. Strategic Retrenchment: Protectionism as Policy

The return of Donald Trump to the White House marks not just a policy swing but a systemic reordering of global commerce. Tariffs, reshoring mandates, and “Buy American” rules are no longer negotiating tactics—they are the starting point. Signature initiatives such as proposed tariffs on imported chips reflect a long-term shift toward industrial policy retrenchment.

Trump’s trade war is now a permanent feature of U.S. policy.[61] South Korea—with its heavy reliance on semiconductor, electric vehicle (EV) battery, and high-tech component exports—faces growing risks of market exclusion across these now-politicized supply chains.

China’s Self-Reliance Drive: Disintermediation, Not Decoupling

Beijing is doubling down on its Made-in-China ambitions, targeting self-sufficiency in chips, batteries, AI, and industrial machinery. This is not mere decoupling. It is disintermediation: the systematic substitution of South Korean and foreign suppliers with domestic alternatives across China’s industrial base—and on top of that, aggressive exports from China of key goods South Korea has long specialized in.

China’s 70 percent self-sufficiency target in semiconductors, its dominance in battery materials, its rapid rise in displays and autos, and its rare earth supply chain strategies are already redrawing the regional trade map.

Domestic Bottlenecks: A Growth Model That No Longer Delivers

Even before these global shocks, South Korea’s growth engine was sputtering at home, as evidenced by:

▪ a two-speed economy with large chaebol-led global productivity while SMEs and services stagnate;

▪ the lowest SME graduation rates in OECD, with most small firms stuck in survival mode;

▪ world-class R&D spending remaining concentrated in manufacturing, with little diffusion to services or small firms; and

▪ the labor market being dominated by SMEs (81 percent of employment), with the lowest share of jobs in large firms (13.9 percent) across OECD countries.

In this environment, simply exporting more—even cutting-edge goods—is no longer sufficient. South Korea now faces the difficult but necessary task of moving from fast follower to first mover. This means shifting from scale-based, export-heavy growth toward broad-based, productivity-led innovation.

Core Strategies for a Next-Generation Economy

Embrace Size Neutrality and Help Competitive Firms Expand

South Korea’s economic ecosystem remains structurally skewed toward small firms—not because they are more productive or innovative, but because policy has made it rational to stay small. For decades, South Korean policymakers have operated under the assumption that small businesses are the backbone of inclusive growth. In practice, however, this has evolved into a system that subsidizes fragmentation, distorts competition, and penalizes firms for growing.

The result is an economy wherein firm size, not productivity, determines market position. Low-margin firms remain afloat for decades with minimal pressure to consolidate, modernize, or exit. Meanwhile, competitive firms—particularly innovative mid-sized companies with growth potential—are crowded out by policies that reward stagnation.

To restore dynamism, South Korea must embrace size neutrality. That means reforming institutions and incentives to support firm growth and competition rather than perpetuating underperformance.

To foster a dynamic, productivity-driven economy, South Korea must reform or abolish the current system—anchored in agencies whose core mission is to protect small firms from market forces—and build a new ecosystem that rewards growth, not status quo preservation.

To restore dynamism, South Korea must embrace size neutrality. That means reforming institutions and incentives to support firm growth and competition—rather than perpetuating underperformance.

Recommended actions:

1. Eliminate or Reform Legacy Structures

▪ Parliament should eliminate the KCCP and the Livelihood-Supporting Industry designation. These frameworks are emblematic of outdated industrial thinking and restrict competition by barring larger firms from entering “protected” sectors such as food service, publishing, and laundromats—regardless of efficiency or consumer benefit. Such rules entrench inefficiency, limit economies of scale, and lock talent and capital into low-productivity traps. These institutions should be phased out entirely. The KCCP states on its website that its mission is to alleviate economic polarization.[62] If that is the case, then phasing out zombie firms—not shielding them through outdated protections—should be a top priority. Policymakers should eliminate such legacy support measures and focus on scaling competitive, innovation-driven firms.

▪ Parliament should craft a new charter for the KFTC to eliminate explicit or implicit mandates that prioritize the protection of small firms as a class. Instead, it should adopt a size-neutral competition framework that focuses on firm conduct—targeting anticompetitive behavior regardless of firm size.

▪ The KFTC should withdraw its push for both the PCPA and the PAB. Before adopting the PCPA as a new ex ante regulatory regime, the KFTC should rigorously assess whether genuine market failures exist in digital markets—such as persistent exclusionary conduct or suppressed innovation harming consumers—that cannot be addressed through existing tools. In the absence of such evidence, South Korea should defer broad structural regulation and instead focus on enforcing and refining its current competition law framework. Likewise, the PAB to the MRFTA, while presented as an ex post tool, effectively replicates DMA-style provisions—such as structural presumptions and expanded theories of harm—into traditional antitrust law. This hybrid approach risks regulatory overreach without clear justification, particularly when existing laws already provide the KFTC with adequate tools to address genuinely anticompetitive conduct. The KFTC should favor targeted, evidence-based refinements to current enforcement mechanisms.

Policy instruments—grants, credit, procurement preferences—should be redesigned around this mission of “graduation,” with clear productivity thresholds and firm-level targets.

▪ The new administration should reconstitute the MSS into a new Ministry of Enterprise Growth. The revised ministry would shift its mandate from protection to progression—from sustaining small firms to enabling scale—with a core focus on helping competitive SMEs graduate into mid-sized and large firms through digital adoption, platform integration, and mergers and acquisitions. Policy instruments—grants, credit, procurement preferences—should be redesigned around this mission of “graduation,” with clear productivity thresholds and firm-level targets.

▪ Eliminate size-based tax distortions. South Korea should adopt a size-neutral corporate tax regime. The current preferential rates for SMEs—ranging from 10 percent to 20 percent—create perverse incentives for firms to remain small and avoid surpassing thresholds such as 10 billion KRW in revenue or having only five employees. A unified tax structure would reduce growth disincentives and foster a level playing field.

▪ Redirect SME support to productivity gains. Rather than blanket subsidies, SME programs should deliver targeted, performance-linked assistance. All support should be conditioned on measurable productivity improvements—such as ERP implementation, digital adoption, or workforce upskilling. Existing subsidies should be converted into competitive grants or concessional loans tied to output metrics.

2. Create or Initiate New Institutions

▪ Launch a graduation accelerator fund. The government should establish a dedicated fund to promote consolidation, mergers and acquisitions, and platform integration in over-fragmented service sectors—such as food service, tutoring, and personal care. These sectors are often protected under SME-friendly regulations, yet remain low productivity and oversaturated. The fund would offer scale-up capital and operational support to help viable firms “graduate” from microenterprise status.

▪ Establish a microbusiness exit and reallocation fund. To reduce labor misallocation and improve workforce matching, South Korea should create a fund to facilitate the orderly exit of inefficient sole proprietorships and self-employed enterprises. Exit support should be paired with targeted reskilling subsidies and job placement programs that link displaced workers to higher-productivity employers, particularly in manufacturing and technology-intensive sectors.

In sum, South Korea’s SME and service sector policy must move away from reflexive protectionism. The country’s next growth chapter will depend on fostering competition, scaling up productivity, and ensuring that success is based on outcomes—not organizational form.

Scale Domestic Productivity Across All Sectors and Bridge the Digital Divide

Over 70 percent of South Korean workers are employed in the service sector, yet productivity in these industries remains less than half that of manufacturing. Sectors such as retail, logistics, construction, agriculture, and traditional markets operate with limited digitization and low adoption rates of automation, cloud, or data tools.

South Korea should take the following actions:

▪ Urgently develop sector-specific strategies among science and technology agencies to boost productivity in lagging areas through tailored digital tools—such as AI-enabled logistics, smart farming, and ERP-based operations in construction.

▪ Accelerate technology adoption in low-productivity sectors. Industries designated under livelihood and SME-suitable protections should shift from regulatory shelter to modernization and scale-up. The country should launch a targeted digital adoption program for traditional sectors—agriculture, construction, logistics, and retail—combining vouchers, training, and advisory services. Continued support should be conditional not on firm size, but rather on outcomes such as ERP installation, AI adoption, data analytics integration, core material management, automation, and measurable value-added-per-worker increases within five years.

▪ Expand technology tax credits to all firms—regardless of size or sector—that adopt ERP, AI, or robotics by building a national productivity dashboard to monitor sectoral output gains and digital adoption in real time.

▪ Establish a productivity-centered labor framework. to transition from time-based to performance-based labor metrics, develop sector-specific productivity benchmarks, and align public sector evaluations and procurement standards with output-driven criteria. This shift would help reorient labor incentives from hours worked to value-added per worker.

▪ Modernize infrastructure for innovation diffusion by building a national productivity dashboard to track sectoral output gains and digital adoption in real time.

▪ Replace South Korea’s permission-based regulatory system with a negative-list approach that enables innovation by default. Unlike in jurisdictions where experimentation is allowed unless explicitly banned, South Korea’s current framework delays new business models until regulations are in place—undermining first-mover advantages in fast-moving digital sectors. A politically neutral “control tower” with cross-agency authority is needed to coordinate tech policy, reduce regulatory fragmentation, and ensure that innovation is not held back by outdated rulebooks.

South Korea’s next productivity surge will not come from labs and chip fabs alone. It will depend on bringing modern tools to the bottom of the economy—where most people work. A productivity playbook that prioritizes digital diffusion, sectoral modernization, and output-based labor incentives is essential for inclusive, future-proof growth.

Modernize Labor Markets and Human Capital for the Innovation Economy

An innovative-driven economy requires a labor system that’s built for mobility, reskilling, and growth. South Korea must expand high-quality jobs by scaling up mid- and large-sized firms while overhauling labor and education frameworks to support career transitions, lifelong learning, and global talent attraction.

A productivity playbook that prioritizes digital diffusion, sectoral modernization, and output-based labor incentives is essential for inclusive, future-proof growth.

Additional recommended actions:

▪ Expand the share of high-quality jobs by growing large enterprises. Shift from protecting small-scale employment to scaling high-quality employment. Encourage SME consolidation and platform integration not only as economic policy, but also as labor policy. Focus support on firms that can offer stable wages, benefits, and advancement opportunities at scale.

▪ Build a “closure-to-reemployment” safety net. Establish a permanent labor transition framework for displaced workers—particularly those exiting low-productivity SMEs or changing industries. Offer time-limited basic income, retraining stipends, and job placement services tied to growth sectors. Create regional reemployment hubs linked to mid-sized and large employers, especially in emerging tech and green industries.

▪ Design a flexible and fair labor framework. Replace rigid employment rules with balanced flexibility. Allow contract and hours-based adjustments while preserving key protections such as severance, insurance, and leave benefits. Enable phased re-entry for caregivers, career switchers, and older workers—turning underutilized labor into productive capacity.

▪ Transform universities into lifelong learning institutions. Redefine higher education as a dynamic, modular ecosystem. Encourage stackable credentials, part-time and evening options, and industry-aligned curricula for adults. Tie funding to job placement and upskilling outcomes, not just enrollment. Position universities as central infrastructure for lifelong workforce development.

▪ Create a global talent mobility package. Seize the window of opportunity created by restrictive U.S. immigration policies. Launch a South Korea–United States Tech Talent Exchange modeled on student visa systems, allowing engineers, researchers, and entrepreneurs to rotate across borders. Complement this with visa packages for global start-up founders—including housing assistance, language training, and family support.

If South Korea is to remain competitive in an era of demographic contraction, it must make a deliberate shift: from labor rigidity to mobility, from fragmentation to consolidation, and from education to lifelong capability-building. A dynamic innovation economy requires a dynamic labor system—and the time to build it is now.

Conclusion: Toward a Productivity-Led Growth Model

South Korea’s next economic transformation will not be driven by exports alone—nor will it come from protecting the status quo. In the face of geopolitical fragmentation, technological disruption, the rise of China as a techno-economic juggernaut, and demographic decline, South Korea must transition from a model based on scale and specialization to one centered on broad-based, performance-driven innovation.

The Trump and China 2.0 era is not just a policy challenge—it is a structural test. South Korea’s resilience will depend on its ability to evolve beyond the fast-follower playbook.

That transition requires three core shifts: first, toward size-neutrality, replacing SME protectionism with support for scalable, productive firms—regardless of size; second, toward domestic diffusion, ensuring digital and productivity tools reach low-performing sectors and workers at the base of the economy; and third, toward human capital and labor flexibility, enabling people to adapt, move, and thrive in a dynamic economy.

The Trump and China 2.0 era is not just a policy challenge—it is a structural test. South Korea’s resilience will depend on its ability to evolve beyond the fast-follower playbook. To lead in a fragmented global order, South Korea must compete on productivity, not just price; on systems, not just sectors. That will take courage, reform, and a national commitment to growth through diffusion—not protection.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Meghan Ostertag, research assistant for economic policy at ITIF, and Lilla Nóra Kiss, Senior Policy Analyst Schumpeter Project on Competition Policy. The authors would also like to thank Randolph Court for his editorial assistance.

Any errors or omissions are the authors’ responsibility alone.

About the Authors

Dr. Robert D. Atkinson (@RobAtkinsonITIF) is the founder and president of ITIF. His books include Technology Fears and Scapegoats: 40 Myths About Privacy, Jobs, AI and Today’s Innovation Economy (Palgrave McMillian, 2024), Big Is Beautiful: Debunking the Myth of Small Business (MIT, 2018), Innovation Economics: The Race for Global Advantage (Yale, 2012), Supply-Side Follies: Why Conservative Economics Fails, Liberal Economics Falters, and Innovation Economics Is the Answer (Rowman Littlefield, 2007), and The Past and Future of America’s Economy: Long Waves of Innovation That Power Cycles of Growth (Edward Elgar, 2005). He holds a Ph.D. in city and regional planning from the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

Sejin Kim is a tech policy analyst specializing in AI, blockchain, and semiconductors for ITIF’s Center for Korean Innovation and Competitiveness. Drawing on technology journalism experience bridging South Korean and U.S. tech ecosystems, she brings cross-cultural insights into national competitiveness and policy dynamics. Notable publications include “On the Recent Development of Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC)” (December 2020, listed in Reuters Refinitiv), “WeMix, Web3 Gaming and Ethics” (January 2023), and “2025 Global Tech Trends: 17 of The Trend Revolution is Coming” (November 2024).

About ITIF

The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) is an independent 501(c)(3) nonprofit, nonpartisan research and educational institute that has been recognized repeatedly as the world’s leading think tank for science and technology policy. Its mission is to formulate, evaluate, and promote policy solutions that accelerate innovation and boost productivity to spur growth, opportunity, and progress. For more information, visit itif.org/about.

About Center for Korean Innovation and Competitiveness

As part of the Washington DC-based ITIF, the Center for Korean Innovation and Competitiveness develops actionable policy solutions to help South Korea navigate its next economic chapter. The Center’s mission is to strengthen South Korea’s long-term competitiveness by advancing its shift to an innovation-driven economy—rooted in emerging tech industries, industrial scale-up, and labor market reform. The Center engages with stakeholders across government, industry, and academia in both South Korea and the United States. For more information, visit, itif.org/centers/korea.

Endnotes

[1]. 중소기업벤처부(MSS), ‘21년 기준 중소기업・소상공인 771만 개, 전체 기업의99.9%’, 2023년 8월 24일, https://www.mss.go.kr/site/smba/ex/bbs/View.do?cbIdx=86&bcIdx=1043937&parentSeq=1043937.

[2]. 한국생산성본부(KPC), “생산성통계 DB.” Labor Productivity per Employed Person (PPP Adjusted, US$), https://stat.kpc.or.kr/integration/index.

[3]. 고영선(2022), 더 많은 대기업일자리가 필요하다. (KDI Focus No. 132)Korea Development Institute. https://www.kdi.re.kr/kdipreview/doc.html?fn=18232_47991&rs=/kdidata/preview/pub.

[4]. 중소기업벤처부(MSS), 2022년 기준 「중소기업 기본통계」 결과 발표. 2024년08월29일, https://www.mss.go.kr/site/smba/ex/bbs/View.do?cbIdx=86&bcIdx=1052875&parentSeq=1052875; 중소기업벤처부(MSS), 중소기업 고용 동향 분석과 시사점, 2025년3월11일, https://mss.go.kr/site/smba/foffice/ex/linkage/linkageView.do?target=R001&cont_knd=R001&b_idx=1583.

[5]. 통계형(KOSTAT), 2020년 기준 경제총조사 결과, 2022년6월28일, https://kostat.go.kr/synap/skin/doc.html?fn=7dfb11df2cd7fcd1a34c84bf71679f1a2a6d364e7df31cfc19b6c1ab15627fb5&rs=/synap/preview/board/10920/.

[6]. OECD Structural and Demographic Business Statistics (ISIC Rev. 4) (database), https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/oecd-economic-surveys-korea-2024_c243e16a-en/full-report/red-light-green-light-reforms-to-boost-productivity_1e59e1af.html#section-d1e4824-b308ebcf91.

[7]. 한국생산성본부(KPC), “생산성통계 DB.” https://stat.kpc.or.kr/integration/index.

[8]. 한국생산성본부(KPC), “생산성통계 DB.” https://stat.kpc.or.kr/integration/index.

[9]. 한국은행(BoK) ‘경제활동별 GDP 통계’, 통계청 ‘산업별 취업자통계’; 국회입법조사처, 서비스업 생산성진단 및 제고방안, 아슈와논점 제 2321호, 2025년2월5일, https://www.nars.go.kr/report/view.do?cmsCode=CM0043&brdSeq=46771.

[10]. Ibid.

[11]. Ibid.

[12]. OECD, Productivity by Industry, Agriculture, gross value added per person employed, https://www.oecd.org/en/data/indicators/value-added-by-activity.html.

[13]. OECD, Productivity by industry: Financial and insurance activities; accessed April 10, 2025, https://data-explorer.oecd.org/vis?tm=construction%20productivity&pg=0&hc[Topic]=&hc[Economic%20activity]=&snb=199&vw=tb&df[ds]=dsDisseminateFinalDMZ&df[id]=DSD_PDB%40DF_PDB_ISIC4_I4&df[ag]=OECD.SDD.TPS&df[vs]=1.0&dq=JPN%2BKOR%2BPOL%2BGBR%2BDEU%2BCAN%2BAUS.A.GVAEMP.K.IX....&pd=2012%2C2023&to[TIME_PERIOD]=false.

[14]. CT services are represented by Information and Communications (KISC Code J), consistent with OECD and Statistics Korea classifications of the ICT service sector.

[15]. Korean Productivity Center(KPC), “생산성 통계 DB.” https://stat.kpc.or.kr/integration/index.

[16]. OECD, Productivity by industry: services of the business economy excluding real estate; accessed April 10, 2025), https://data-explorer.oecd.org/vis?tm=construction%20productivity&pg=0&hc[Topic]=&hc[Economic%20activity]=&snb=199&vw=tb&df[ds]=dsDisseminateFinalDMZ&df[id]=DSD_PDB%40DF_PDB_ISIC4_I4&df[ag]=OECD.SDD.TPS&df[vs]=1.0&dq=JPN%2BKOR%2BPOL%2BGBR%2BDEU%2BCAN%2BAUS.A.GVAEMP.GTNXL.IX....&pd=2012%2C2023&to[TIME_PERIOD]=false.

[17]. 통계청(Statistics Korea), 2025년 3월 고용동향, https://kostat.go.kr/synap/skin/doc.html?fn=9304d2a7393b4f3b3a49fdf6d103a974cad30953a1c3fe97e08a3c298c26c0b0&rs=/synap/preview/board/210/.

[18]. OECD, OECD Data Archive, Multifactor Productivity, annual; accessed April 11, 2025, https://data-explorer.oecd.org/vis?lc=en&df[ds]=DisseminateArchiveDMZ&df[id]=DF_DP_LIVE&df[ag]=OECD&df[vs]=&av=true&pd=%2C2022&dq=USA%2BKOR%2BOECD%2BOAVG.MFP...A&to[TIME_PERIOD]=false&vw=tb.

[19]. OECD, OECD Economic Surveys: Korea (Paris: OECD, July 2024), https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2024/07/oecd-economic-surveys-korea-2024_9343c046/c243e16a-en.pdf.

[20]. Chalaux, T. and Y. Guillemette (2019), “The OECD potential output estimation methodology,” OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1563, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/4357c723-en.

[21]. OECD (2018), OECD Economic Surveys: Korea 2018, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-kor-2018-en.

[22]. OECD (2020), OECD Economic Surveys: Korea 2020, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/2dde9480-en.

[23]. 고영선(2022), 더 많은 대기업일자리가 필요하다. (KDI Focus No. 132)Korea Development Institute. https://www.kdi.re.kr/kdipreview/doc.html?fn=18232_47991&rs=/kdidata/preview/pub.

[24]. Robert D. Atkinson and Michael Lind, Big is Beautiful: Debunking the Myth of Small Business (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2018).

[25]. 고용노동부(MOEL), 2023년 고용형태별근로실태조사 보고서, 44페이지, https://www.xn--vb0b6f546cmsg6pn.com/sub/reference/reference01.asp?mode=view&bid=1&idx=1155.

[26]. 고용노동부, 「일가정양립실태조사」, 2022, 2025.04.28, 육아휴직제도-사용가능현황, https://kosis.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?sso=ok&returnurl=https%3A%2F%2Fkosis.kr%3A443%2FstatHtml%2FstatHtml.do%3Fconn_path%3DI2%26tblId%3DDT_118045_A015%26orgId%3D118%26.

[27]. OECD, Pensions at a glance; accessed April 10, 2025, https://data-explorer.oecd.org/vis?tm=pensions&pg=0&hc[Unit%20of%20measure]=&snb=174&df[ds]=dsDisseminateFinalDMZ&df[id]=DSD_PAG%40DF_PAG&df[ag]=OECD.ELS.SPD&df[vs]=1.0&dq=.A.CRPLF22%2BFRPLF22%2BGPRR100%2BATRW%2BATRAEP%2BATRPPAE%2BNPRR100%2BGPW100%2BNPW100%2BFR%2BLE%2BER%2BOAWAR%2BELMEA%2BEYLME%2BEDIOP%2BPTOP%2BOCOP%2BCIOP%2BEIOP%2BAWGW%2BOAIP%2BPEP%2BPPEP....&pd=2019%2C2022&to[TIME_PERIOD]=true.

[28]. OECD (2024), Education at a Glance 2024: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/c00cad36-en.

[29]. OECD (2024), Survey of Adults Skills 2023: Korea, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/survey-of-adults-skills-2023-country-notes_ab4f6b8c-en/korea-republic-of_5f95963c-en.html.

[30]. Republic of Korea. (1987). Constitution of the Republic of Korea, Article 123, Clause 3, https://www.law.go.kr/lsLinkProc.do?lsClsCd=L&lsNm=%EB%8C%80%ED%95%9C%EB%AF%BC%EA%B5%AD%ED%97%8C%EB%B2%95&lsId=prec20080109&joNo=012300&efYd=20080109&mode=11&lnkJoNo=undefined.

[31]. Korea Development Institute, Korea Small Business Institute and Research Institute, for the Assessment of Economic and Social Policies, In-Depth Study on Fiscal, Programs 2010: the SME Sector, Seoul (2011) (in Korean); Robert Atkinson, “The Real Korean Innovation Challenge: Services and Small Businesses,” Korea’s Economy 2014 (Vol. 30, pp. 47–54), Korea Economic Institute of America, https://keia.org/publication/the-real-korean-innovation-challenge-services-and-small-businesses/.

[32]. OECD, OECD Economic Surveys: Korea (Paris: OECD, July 2024), https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2024/07/oecd-economic-surveys-korea-2024_9343c046/c243e16a-en.pdf.

[33]. Bank of Korea. (n.d.), SME mandatory lending system, https://terms.naver.com/entry.naver?docId=299160&cid=42103&categoryId=42103.

[34]. OECD, OECD Economic Surveys: Korea (Paris: OECD, July 2024), https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2024/07/oecd-economic-surveys-korea-2024_9343c046/c243e16a-en.pdf;

1. Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy. 2. Ministry of Science and ICT. 3. Ministry of SMEs and Startups. 4. Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries. 5. Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs. 6. Ministry of Employment and Labor. 7. Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism. 8. Ministry of Environment. 9. Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport. 10. Ministry of Economy and Finance. 11. Financial Services Commission. 12. Ministry of Interior and Safety. 13. Korean Intellectual Property Office. 14. Forest Service. 15. Public Procurement Service. 16. Ministry of Food and Drug Safety. 17. Communications Commission. 18. Customs Service.

[35]. Ibid.

[36]. OECD, OECD Economic Surveys: Korea (Paris: OECD, July 2024), https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2024/07/oecd-economic-surveys-korea-2024_9343c046/c243e16a-en.pdf.

[37]. Ibid.

[38]. KDI 경제정보센터,「소상공인 생계형 적합업종 제도」 본격 시행, <붙임> 시행령주요내용, 생계형 적합업종 지정 절차 및 중소기업 적합업종과 생계형 적합업종 비교, https://eiec.kdi.re.kr/policy/materialView.do?num=183386&topic=.

[39]. 동반성장위원회, 소상공인 생계형 적합업종 지정현황, 검색일: 2025년 4월 17일, https://www.winwingrowth.or.kr/site/cntnts/CNTNTS_030.do.

[40]. OECD, SME and Entrepreneurship Outlook 2023, https://www.oecd.org/industry/smes/outlook/; Atkinson, “The Real Korean Innovation Challenge: Services and Small Businesses.”

[41]. Minseo Kim, Seongbae Lim, and Yeong-wha Sawng, “A Study on Growth Engines of Middle Market Enterprise (MME) of Korea Using Meta-Analysis” Sustainability 14, no. 3, 2022, 1469, https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031469.

[42]. The purpose of the Fair Transactions in Subcontracting Act (hereinafter referred to as “the Subcontracting Act”) is to prevent prime contractors (mainly, large enterprises) from abusing their dominant positions in the course of subcontracting transactions, protecting interests of subcontractors that are in a financially weaker position (mainly, small and medium enterprises), and ultimately establish a fair order in subcontracting transactions. Fair Trade Commission, “Subcontract Policy,” https://www.ftc.go.kr/eng/contents.do?key=550.

[43]. Ibid.

[44]. Korea Legislation research Institute(KLRI, 2024), ACT ON THE PROMOTION OF COLLABORATIVE COOPERATION BETWEEN LARGE ENTERPRISES AND SMALL-MEDIUM ENTERPRISES, https://elaw.klri.re.kr/eng_mobile/viewer.do?hseq=64589&type=part&key=28.

[45]. Lilla Nóra Kiss, “Why South Korea Should Resist New Digital Platform Laws” (ITIF December 9, 2024), https://itif.org/publications/2024/12/09/why-south-korea-should-resist-new-digital-platform-laws/; Korea Fair Trade Commission, Monopoly Regulation and Fair Trade Act (partial amendment, Act No. 11406, March 21, 2012), unofficial English translation by Korea Legislation Research Institute, https://elaw.klri.re.kr/eng_service/lawView.do?hseq=25318&lang=ENG; Joseph V. Coniglio et al., “A Policymaker’s Guide to Digital Antitrust Regulation,” (ITIF, March 31, 2025), https://itif.org/publications/2025/03/31/policymakers-guide-digital-antitrust-regulation/.

[46]. Regulation (EU) 2022/1925 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 September 2022 on contestable and fair markets in the digital sector and amending Directives (EU) 2019/1937 and (EU) 2020/1828 (Digital Markets Act), Official Journal (OJ), L 265/1, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32022R1925&qid=1698952729244.

[47]. 공정거래위원회, “쿠팡(주) 및 씨피엘비(주)의 위계에의한 고객유인행위 건 제재”, https://www.ftc.go.kr/www/selectBbsNttView.do?pageUnit=10&pageIndex=1&searchCnd=all&searchKrwd=%EC%BF%A0%ED%8C%A1&key=12&bordCd=3&searchCtgry=01,02&nttSn=43448.

[48]. 공정거래위원회, “플랫폼공정경쟁 촉진 및 티몬·위메프 사태 재발방지를 위한 입법방향” 2024년9월9일, https://www.ftc.go.kr/viewer/synap/skin/doc.html?fn=2024090906264410797_000001.hwp&rs=/viewer/synap/preview/; “수수료 부담 완화 등 소상공인, 소비자, 배달플랫폼 간 상생방안 도출 적극 지원”, 2024년10월8일, https://www.ftc.go.kr/www/selectBbsNttView.do?pageUnit=10&pageIndex=3&searchCnd=all&searchKrwd=%ED%94%8C%EB%9E%AB%ED%8F%BC&key=12&bordCd=3&searchCtgry=01,02&nttSn=43613.

[49]. 중소기업연구원, ‘생계형적합업종 제도’의 주요 쟁점 및 향후 과제, 2018, https://db.kosi.re.kr/kosbiDB/front/subjectResearchDetail?dataSequence=J180702K01&issueID=333b87901ea64174998dca7833674a88.

[50]. 중소벤처기업부, 2022년 중소기업 세제혜택 개요, https://www.bizinfo.go.kr/web/lay1/bbs/S1T122C128/AS/74/view.do?pblancId=PBLN_000000000078224.

[51]. 법제처국가법령정보센터, 근로기준법 [법률 제20520호, 2024. 10. 22., 일부개정], https://www.law.go.kr/%EB%B2%95%EB%A0%B9/%EA%B7%BC%EB%A1%9C%EA%B8%B0%EC%A4%80%EB%B2%95/%EC%A0%9C11%EC%A1%B0.

[52]. 국세청, 부가가치세 개요, https://www.nts.go.kr/nts/cm/cntnts/cntntsView.do?cntntsId=7693&mi=2272.

[53]. 한겨레, “중소기업 매출 기준 1500→1800억…혁신 유도 대신 ‘피터팬’ 키울라”, 2025년5월1일, https://www.hani.co.kr/arti/economy/economy_general/1195396.html.

[54]. OECD Data Archive, Indicator: GDP per hour worked, Subject: Total, Measure: US dollars, Frequency: Annual, https://data-explorer.oecd.org/vis?lc=en&tm=gdp%20per%20hour%20worked&pg=0&hc[Measure]=&hc[Unit%20of%20measure]=&snb=14&vw=tb&df[ds]=dsDisseminateFinalDMZ&df[id]=DSD_PDB%40DF_PDB_LV&df[ag]=OECD.SDD.TPS&df[vs]=1.0&dq=KOR%2BDEU%2BAUS%2BUSA%2BGBR%2BJPN%2BPOL.A.GDPHRS..USD_PPP_H.Q...&pd=2011%2C2023&to[TIME_PERIOD]=false.

[55]. 전국경제인연합회(FKI), 서비스업 고용구조 및 노동생산성 국제비교, 2022년 5월 1일, https://m.fki.or.kr/bbs/bbs_view.asp?cate=news&content_id=09ba86e3-b375-485d-90ed-33282533efd7.

[56]. 통계청(KOSTAT),「KOSTAT 통계플러스」2024년 봄호, 2024년3월25일, https://kostat.go.kr/board.es?mid=a10301010000&bid=246&list_no=430060&act=view&mainXml=Y.

[57]. OECD, “OECD Digital Economy Outlook,” Authors’ elaboration based on OECD (2023[5]) and Eurostat (2024[95]), https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/oecd-digital-economy-outlook-2024-volume-1_a1689dc5-en/full-report/component-7.html#sect-65.

[58]. KBR경영연구소, [심층분석]왜 한국만 자영업자가 이렇게 많을까? 세계 최고 수준 자영업 비율의 충격과 해법, 2025년5월2일, https://www.koreabizreview.com/detail.php?number=6068&thread=24.

[59]. OECD, “OECD Digital Economy Outlook.”

[60]. Korea Development Institute (KDI) (2021), Digital Transformation Strategy for Digital-Based Growth, https://www.kdi.re.kr/eng/research/reportView?pub_no=17620.

[61]. See: Robert D. Atkinson and Stephen Ezell, “Toward Globalization 2.0: A New Trade Policy Framework for Advanced-Industry Leadership and National Power” (ITIF, March 2025), https://itif.org/publications/2025/03/24/globalization2-a-new-trade-policy-framework/.

[62]. 동반성장위원회(KCCP), “Who we are-Our Purpose”, 검색일: 2025년5월4일, https://www.winwingrowth.or.kr/site/cntnts/CNTNTS_009.do.

Editors’ Recommendations

Related

December 25, 2025

Korea’s $700B Export Record Is an Achievement, Not a Growth Strategy

October 31, 2025