Comments to OMB Regarding Deregulation

Contents

Clarify Bayh-Dole March-in Rights Provisions 2

Rescind NIH Access Planning Policy 4

Maintain FDA Funding Structure Through PDUFA. 6

Make Up Cuts to Indirect Research Costs Through Increased Biomedical R&D Funding. 6

Rescind FRA Regulation Requiring Two-Person Train Crews 7

Clarify Requirements for Manually Operated Driving Controls 7

Protect America’s Innovative Clean Energy Technologies 7

Streamline Regulatory Permitting for Semiconductors 9

Introduction

ITIF is an independent 501(c)(3) nonprofit, nonpartisan research and educational institute that has been recognized repeatedly as the world’s leading think tank for science and technology policy. ITIF focuses on a host of critical issues at the intersection of technological innovation and public policy—including economic issues related to innovation, productivity, and competitiveness; technology issues in the areas of information technology and data, broadband telecommunications, advanced manufacturing, life sciences, and clean energy; and overarching policy tools related to public investment, regulation, antitrust, taxes, and trade. ITIF’s goal is to provide policymakers with high-quality information, analysis, and actionable recommendations they can trust. To that end, ITIF adheres to a high standard of research integrity with an internal code of ethics grounded in analytical rigor, original thinking, policy pragmatism, and editorial independence.

ITIF is pleased to offer this input in response to the OMB’s request for information on deregulation.[1]

Clarify Bayh-Dole March-in Rights Provisions

The Patent and Trademark Act Amendments of 1980, commonly referred to as “the Bayh-Dole Act” in recognition of its principal sponsors Birch Bayh (D-IN) and Bob Dole (R-KS), established a uniform federal patent policy allowing funding recipients to retain patent rights on inventions made with federal funding, subject to certain conditions.[2]

The legislation has played a catalytic role in advancing America’s innovation economy, in particular by helping to turn American universities into engines of innovation. The Economist would hail the Bayh-Dole Act as, “possibly the most inspired piece of legislation to be enacted in America over the past half-century.” It noted that the legislation “unlocked all the inventions and discoveries that had been made in laboratories throughout the United States with the help of taxpayers’ money” and “more than anything, this single policy measure helped to reverse America's precipitous slide into industrial irrelevance.”[3]

Before Bayh-Dole (i.e., pre-1980), the federal government had a very weak track record in commercializing the intellectual property (IP) it owned as a result of publicly funded research conducted at universities (or federal laboratories). As late as 1978, the federal government had licensed less than 5 percent of the as many as 30,000 patents it owned.[4] And one assessment found that “not a single drug had been developed when patents were taken from universities [by the federal government.”[5] Likewise, throughout the 1960s and 1970s, many American universities shied away from direct involvement in the commercialization of research.[6] Indeed, before the passage of Bayh-Dole, only a handful of U.S. universities even had technology transfer or patent offices.[7]

But passage of the Bayh-Dole Act led to an almost immediate increase in academic patenting activity and the formation of new start-up companies as a result thereof. For instance, while only 55 U.S. universities had been granted a patent in 1976, 240 universities had been issued at least one patent by 2006.[8] Similarly, while only 390 patents were awarded to U.S. universities in 1980, by 2009, that number had increased to 3,088—and by 2015, to 6,680. Another analysis found that in the first two decades of Bayh-Dole (i.e., 1980 to 2002) American universities experienced a tenfold increase in their patents and had spun out or created more than 2,200 companies to exploit their technology.[9]

This impact has only continued to increase. From 1996 to 2020, U.S. academic technology transfer activities have led to 554,000 inventions disclosed, 141,000 U.S. patents issued, 18,000 new start-ups formed, and the creation of over 200 new drugs and vaccines.[10] Moreover, over that time, academic technology transfer contributed $1.9 trillion to U.S. gross industrial output, $1 trillion to U.S. gross domestic product (GDP), and over 6.5 million jobs supported.[11] The Bayh-Dole Act fundamentally underpins this academic technology transfer ecosystem.

The Bayh-Dole Act included so-called “march-in rights” that permit the government, in specified circumstances, to require patent holders to grant a “nonexclusive, partially exclusive, or exclusive license” to a “responsible applicant or applicants.”[12] The architects of the Bayh-Dole Act principally intended for march-in rights to be used to ensure patent owners commercialized their inventions.[13] As Senator Birch Bayh himself explained, “When Congress was debating our approach fear was expressed that some companies might want to license university technologies to suppress them because they could threaten existing products. Largely to address this fear, we included the march-in provisions.”[14]

The Bayh-Dole Act proscribes four specific instances in which the government is permitted to exercise march-in rights:

1. If the contractor or assignee has not taken, or is not expected to take within a reasonable time, effective steps to achieve practical application of the subject invention;

2. If action is necessary to alleviate health or safety needs not reasonably satisfied by the patent holder or its licensees;

3. If action is necessary to meet requirements for public use specified by federal regulations and such requirements are not reasonably satisfied by the contractor, assignee, or licensees; or

4. If action is necessary, in exigent cases, because the patented product cannot be manufactured substantially in the United States.[15]

In other words, lower prices are not one of the rationales laid out in the act. In fact, as senators Bayh and Dole have themselves noted, the Bayh-Dole Act’s march-in rights were never intended to control or ensure “reasonable prices.”[16] Indeed, as Senators Bayh and Dole wrote in a 2002 Washington Post op-ed titled, “Our Law Helps Patients Get New Drugs Sooner,” the Bayh-Dole Act:

Did not intend that government set prices on resulting products. The law makes no reference to a reasonable price that should be dictated by the government. This omission was intentional; the primary purpose of the act was to entice the private sector to seek public-private research collaboration rather than focusing on its own proprietary research.[17]

In 2023, the Biden administration sought to issue guidelines, via the “Draft Interagency Guidance Framework” that would permit governmental use of march-in rights on the basis of the resulting price of a product, such as a drug or an electric vehicle battery.[18] But while adding reasonable price terms to march-in rights legislation could in theory reduce prices by spurring more competition, the reality is it would not do that because companies would not engage with universities in licensing technologies in the first place if they were aware that the risk to their investments would be extremely high. Indeed, if a government ever had the capacity to march in decades later and compulsorily license the IP underpinning a novel biologic drug on the grounds that some of it may have in part been contributed by federally funded scientific research—and now the government deems the price for that drug “unreasonable”—it would seriously undermine the mechanics of America’s life-sciences innovation system, giving enterprises considerable pause about investing the additional hundreds of millions, even billions, required to bring innovative drugs to the marketplace.

It's for this reason that a report issued by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) during the first Trump administration called the “Return on Investment Initiative: Draft Green Paper” found that, “The use of march-in is typically regarded as a last resort, and has never been exercised since the passage of the Bayh-Dole Act in 1980.”[19] The report further noted that the, “NIH determined that that use of march-in to control drug prices was not within the scope and intent of the authority.”[20] The Trump administration should build upon the findings of the 2018 NIST Green Paper and affirmatively declare that price is not a legitimate basis for the exercise of Bayh-Dole march-in rights.

Rescind NIH Access Planning Policy

Separately, on January 10, 2025, in one of the Biden administration’s final actions, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) issued an Intramural Research Program (IRP) Access Planning Policy whose objective was to “expand equitable patient access to products that emerge from NIH-owned patents.”[21] The directive required “organizations applying to NIH for certain commercial patent licenses to submit Access Plans to NIH outlining steps they intend to take to promote patient access to those licensed products.”[22] Pricing was a central focus of the Access Planning Policy, the guidance noting that ways applicants could “promote equitable access and affordability in product deployment” could include by “Committing to keep prices in the U.S. equal to those in other developed countries” or by “Committing to price reductions once preset sales, revenue, or profit thresholds are reached.”[23] The Access Planning Policy requires industry licensees to submit continuous and burdensome reports, covering a number of topics that are not required by the Bayh-Dole Act, including how a resulting product would be priced. The Access Planning Policy also potentially creates a mechanism for the agency to revoke a recipient’s license (i.e., if in the agency’s view the license weren’t fulfilling terms of the access plan), even if the license might have subsequently invested considerable sums to bring an innovative product to market.

But bringing a drug to market represents a complex, risky, lengthy, and costly process that can take 14 or more years at costs measured in the billions of dollars. The notion that a small start-up licensing prospective IP in the form of a novel chemical compound from a university is in any kind of position to reliably price a potentially resulting product over a decade and hundreds of millions, if not billions, in further development and clinical trials is simply not realistic.

The U.S. government has tried to include reasonable pricing provisions or guidelines in NIH contracts before. Notable, in 1989, NIH’s Patent Policy Board adopted a policy statement and three model provisions to address the pricing of products licensed by public health service (PHS) research agencies on an exclusive basis to industry, or jointly developed with industry through Cooperative Research and Development Agreements (CRADAs). In doing so, the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) became the only federal agency at the time (other than the Bureau of Mines) to include a “reasonable pricing” clause in its CRADAs and exclusive licenses.[24] The 1989 PHS CRADA Policy Statement asserted:

DHHS has a concern that there be a reasonable relationship between pricing of a licensed product, the public investment in that product, and the health and safety needs of the public. Accordingly, exclusive commercialization licenses granted for the NIH/ADAMHA [Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration] intellectual property rights may require that this relationship be supported by reasonable evidence.

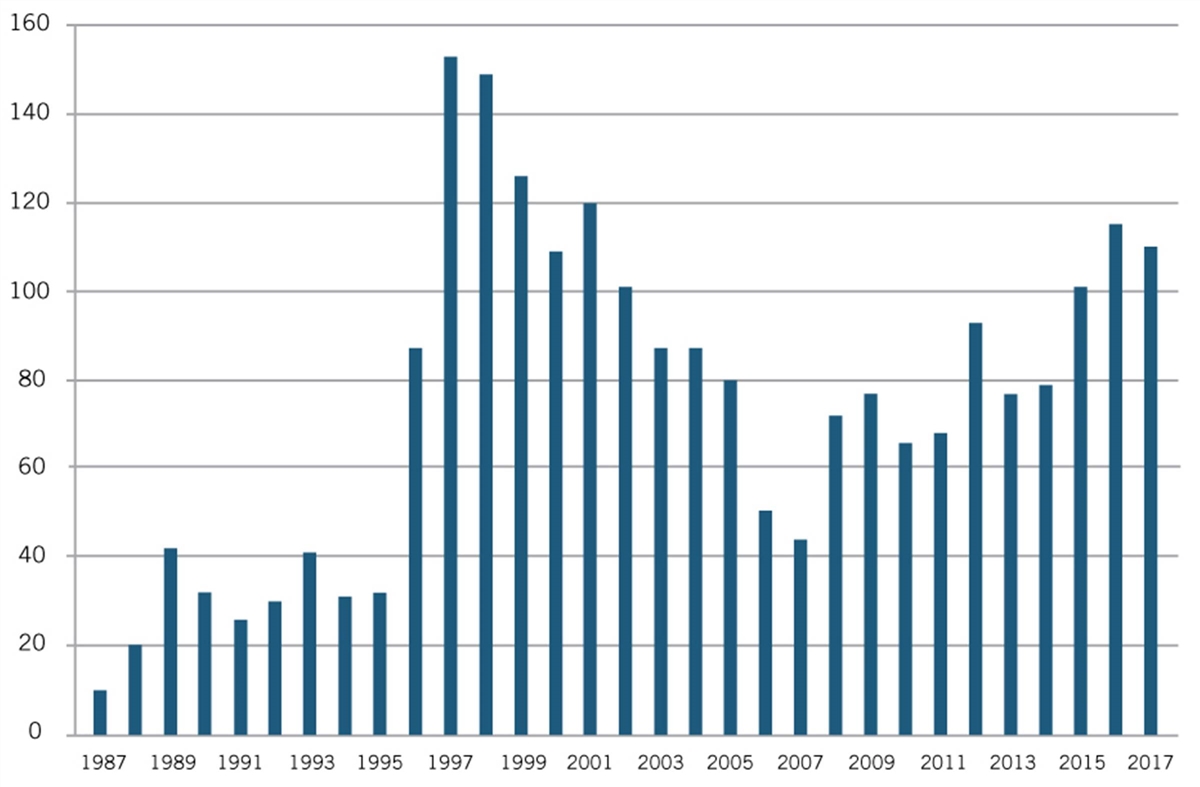

But as Joseph P. Allen notes, such “attempts to impose artificial ‘reasonable pricing’ requirements on developers of government supported inventions did not result in cheaper drugs. Rather, companies simply walked away from partnerships.”[25] Use of CRADAs began in 1987 and rapidly increased until the reasonable pricing requirement hit in 1989, after which they declined through 1995 (see figure 1).

Figure 1: Private-sector CRADAs with NIH, 1987–2017[26]

Recognizing that the only impact of the reasonable pricing requirement was undermining scientific cooperation without generating any public benefits, NIH eliminated the reasonable pricing requirement in 1995. In removing the requirement, then NIH director Dr. Harold Varmus explained, “An extensive review of this matter over the past year indicated that the pricing clause has driven industry away from potentially beneficial scientific collaborations with PHS scientists without providing an offsetting benefit to the public. Eliminating the clause will promote research that can enhance the health of the American people.”[27] As figure 1 shows, after NIH eliminated the requirement in 1995, the number of CRADAs immediately rebounded in 1996, and grew considerably in the following years.

Requiring licenses to accurately predict years in advance how a product resulting from a license of IP would be priced would stifle U.S. biopharmaceutical innovation. The Trump administration should direct the NIH to withdraw its Intramural Research Program Access Planning Policy.

Maintain FDA Funding Structure Through PDUFA

Recent policy shifts under the Trump administration have raised serious concerns about the future of drug development in the United States. Budget and staffing cuts at the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) slow drug research and review processes, undermining the agency’s ability to perform critical regulatory and oversight functions, and delaying access to new therapies.

These cuts also jeopardize the Prescription Drug User Fee Act (PDUFA), enacted in 1992 to allow the FDA to collect industry fees to fund drug review. PDUFA enabled the FDA to hire additional reviewers and reduced median drug review times from over two and a half years in 1987 to about 10 months today, without compromising safety standards.[28]

However, the law includes a “trigger mechanism” requiring Congress to fund the FDA above a baseline set in 1997, adjusted for inflation. If appropriations fall below that threshold, the FDA must return collected fees, significantly hurting its review processes. The Trump administration’s reductions risk activating this mechanism, threatening to reverse decades of progress. To safeguard drug innovation and timely patient access, preserving the PDUFA user fee framework is essential.

Make Up Cuts to Indirect Research Costs Through Increased Biomedical R&D Funding

Despite the importance of federal support for U.S. biopharmaceutical innovation, the Trump administration’s efforts to reduce the size of the federal government have already resulted in decreased funding. One significant cut involves capping indirect costs for National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants at 15 percent, down from an average of 27-28 percent.[29] Indirect costs are vital to “keeping the lights on,” because they cover expenses associated with lab facility maintenance, equipment, and insurance, utilities, and administrative personnel.[30] Even beyond funding new scientific knowledge and technological tools, public funding also cultivates a highly skilled scientific workforce, crucial to continuing biopharmaceutical progress.

While some private foundations offer lower indirect rates than federal agencies, their grants are complementary to federal funding, and universities are able to accept such lower rates precisely because federal grants provide the baseline foundational research support that serves future project-specific funding.[31] Moreover, private foundations tend to prefer supporting specific research projects that align with their funding priorities, which is another reason why broader federal support is so important for scientific progress. Reducing federal funding will discourage research projects that require large-scale investments due to a simple lack of funding, harming U.S. biopharmaceutical innovation.

At a time when the United States is scaling back its life-sciences funding, China is expanding its federal investment in this sector to advance its vision of becoming a global biotechnology superpower. China’s primary science funding agency, the National Natural Science Foundation, has been increasing support for basic research as part of a broader national strategy to strengthen its entire biotechnology sector.[32] As a result, reductions in U.S. federal life-sciences funding risk slowing the development of life-saving treatments and weakening global biopharmaceutical competitiveness. Sustained NIH funding and continued support for indirect costs at prior levels are essential to maintaining U.S. leadership in biopharmaceutical innovation. If the Trump administration maintain the stringent caps on indirect R&D costs, it should balance this by increasing NIH funding for biomedical research.

Rescind FRA Regulation Requiring Two-Person Train Crews

The Office of Management and Budget should rescind the Federal Railroad Administration’s (FRA) regulation requiring two-person train crews. This mandate lacks a foundation in safety data and appears to be driven primarily by labor group pressures rather than evidence-based policy. Technological advances such as Positive Train Control (PTC) and other automatic braking systems are designed specifically to prevent the types of accidents caused by human error, rendering the crew-size mandate obsolete. By enforcing a rigid staffing requirement, the FRA is not only impeding safety innovation but also disincentivizing rail operators from investing in automation that would enhance both efficiency and long-term safety. Eliminating this rule would promote modern rail operations and align U.S. freight rail policy with global best practices.[33]

Clarify Requirements for Manually Operated Driving Controls

The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) should clarify—through regulatory changes or formal interpretation—that existing requirements for manually operated driving controls and certain driver-focused indicators do not apply to vehicles equipped with Level 4 or Level 5 Automated Driving Systems (ADS) that are designed to operate without a human driver.[34] These requirements were developed for traditional vehicles with in-cabin drivers and, when applied to ADS-dedicated vehicles, can impede deployment without offering corresponding safety benefits. Removing or exempting these outdated requirements will support autonomous vehicle innovation and deployment while ensuring that safety regulations are appropriately tailored to the vehicle’s design and use case.

Protect America’s Innovative Clean Energy Technologies

In the waning days of the Biden administration, the Nuclear Research Program at the Department of Energy misguidedly opened up U.S. clean energy technology to the world. The Nuclear Research Program actually mandated that any interventions supported by its funding be given away—even to foreign rivals.[35] The memo, which was not initially made public outside of the DOE National Laboratories, stated:

The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Nuclear Energy (NE) is issuing this guidance regarding the commercialization of NE-funded technologies. With this guidance, NE is establishing a policy preference for the dedication to the public of such technology, where it is made freely available to the public with few or no intellectual property restrictions, or the non-exclusive licensing of technology developed with NE funding. [Emphasis added.]

Recognizing that the contractors who manage National Laboratories for DOE according to Management & Operating (M&O) contracts (DOE National Laboratory contractors) generally have rights under the Bayh-Dole Act, including the right to elect title to federally-funded inventions and license those inventions per the technology transfer mission clauses of M&O contracts this policy is intended to be a significant factor that the National Laboratory M&O contractors are expected to weigh when structuring and negotiating the licensing of NE-funded technologies, even when owned by the contractor. In the extraordinary circumstances in which a National Laboratory wants to exclusively license a NE funded technology, NE expects the National Laboratory M&O contractor to consult with NE leadership and the DOE Patent Counsel prior to entering into such an exclusive license. The purpose of this consultation is to verify that all parties agree that the exclusive license is the best vehicle for advancing DOE’s mission and interests, including maximizing commercialization and broadly disseminating NE-funded technology.

Giving away U.S. nuclear technology is a poor strategy when China has already begun to surpass the United States in the research into and deployment of fourth-generation nuclear reactor technologies and to at least be close to, if not at par, with the United States in nuclear fusion.[36] The DOE should follow established technology licensed practices as codified in the Bayh-Dole Act.

What’s also ironic is that this give away of technology was completely in contravention to a series of sweeping DOE policy changes the agency made in June 2021 that stipulated that all inventions developed with taxpayer funding through DOE Science and Engineering programs be “substantially manufactured” in the United States.[37]

While certainly that is a laudable goal, and while certainly the Bayh-Dole Act forbids the manufacture of federally funded inventions outside the United States, it does permits innovators to seek a waiver from the funding agency if “reasonable but unsuccessful efforts have been made to grant licenses on similar terms to potential licensees that would be likely to manufacture substantially in the United States” or “under the circumstances domestic manufacture is not commercially feasible.”[38]

But that waiver process has been chaotic, inconsistent, and variable by agency. A survey of university tech transfer offices conducted by the Association of University Technology Managers (AUTM) found one-quarter reporting that it took more than one year to receive a waiver request response from the funding agency.[39] The survey included a response that, “The waiver process is completely busted. Not only did we spend precious non-profit research dollars on requesting legal help in navigating the waiver process, it was useless. The end result is that because the company could not get a US waiver, the availability of the product for US patients was blocked. The product is available globally except in the US because of this issue. So, US patients are suffering.” Federal agencies need to be much more alacritous when responding to such waiver requests.

Unfortunately, there are cases where American innovators simply can’t manufacture their products in the United States. Given the hollowing out that’s happened to so much of American manufacturing, and America’s dependence on countries such as China for a variety of rare earths, critical minerals, and inputs to industrial processes such as rare earth magnets, and superabrasives (e.g., diamond cutting tools) (with one report finding that the United States is entirely dependent on China for superabrasive materials, for instance).[40] The best way to deal with this broader challenge would be to craft a serious advanced industry competitiveness strategy for the United States, such that more innovators coming out of America’s universities and national labs could have better opportunity to manufacture their products in the United States.[41]

Streamline Regulatory Permitting for Semiconductors

The stringent environmental review processes that applied to semiconductor facilities built with CHIPS Act funds have delayed some of their construction.[42] CHIPS Act applicants have been required to submit an “A-Z” environmental questionnaire to the Department of Commerce. But as The Wall Street Journal reports:

The most immediate threat to the timely construction is the National Environmental Policy Act [NEPA], which requires large federally funded projects to pass environmental review before grants are released, regardless of whether they have already obtained state and local government permits. Full NEPA reviews took an average of 4.5 years between 2013 and 2018, according to a federal government report.[43]

Observers contend that each year of delay in receiving environmental permitting review adds roughly 5 percent to the cost of a constructing a semiconductor chip plant.[44] The establishment within the Department of Commerce of the United States Investment Accelerator, dedicated to reducing regulatory burdens, speeding up permitting, and coordinating responses to investor issues across multiple federal agencies certainly represents an important step in addressing this challenge.[45]

Thank you for your consideration.

Endnotes

[1] Office of Management and Budget, “Request for Information: Deregulation,” FR Doc. 2025-06316, April 11, 2025, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2025/04/11/2025-06316/request-for-information-deregulation.

[2] Congressional Research Service (CRS), “Pricing and March-In Rights Under the Bayh-Dole Act,” (CRS, December 3, 2024), https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/IF12582.

[3] “Innovation’s Golden Goose,” The Economist, December 12, 2002, http://www.economist.com/node/1476653.

[4] B. Graham, “Patent Bill Seeks Shift to Bolster Innovation,” The Washington Post, April 8, 1978; Ashley J. Stevens et al., “The Role of Public-Sector Research in the Discovery of Drugs and Vaccines” The New England Journal of Medicine Vol. 364:6 (February 2011): 1, https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMsa1008268.

[5] Joseph P. Allen, “When Government Tried March In Rights to Control Health Care Costs,” IPWatchdog, May 2, 2016, http://www.ipwatchdog.com/2016/05/02/march-in-rights-health-care-costs/id=68816/.

[6] Naomi Hausman, “University Innovation, Local Economic Growth, and Entrepreneurship,” U.S. Census Bureau Center for Economic Studies Paper No. CES-WP- 12–10 (July 2012): 5, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2097842.

[7] Louis G. Tornatzky and Elaine C. Rideout, “Innovation U 2.0: Reinventing University Roles in a Knowledge Economy” (State Science and Technology Institute, 2014) 165, https://ssti.org/report-archive/innovationu20.pdf.

[8] Hausman, “University Innovation, Local Economic Growth, and Entrepreneurship,” 7. (Calculation based on NBER patent data.)

[9] John H. Rabitschek and Norman J. Latker, “Reasonable Pricing—A New Twist for March-in Rights Under the Bayh-Dole Act” Santa Clara High Technology Law Journal Vol. 22, Issue 1 (2005), 150, https://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1399&context=chtlj.

[10] Association of University Technology Managers (AUTM), “Driving the Innovation Economy: Academic Technology Transfer in Numbers” (AUTM, 2024), https://autm.net/AUTM/media/SurveyReportsPDF/AUTM-Infographic-23-DIGITAL.pdf.

[11] Ibid.

[12] John R. Thomas, “March-In Rights Under the Bayh-Dole Act” (Congressional Research Service, August 2016), 7, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R44597.pdf.

[13] Stephen Ezell, “The Bayh-Dole Act’s Vital Importance to the U.S. Life-Sciences Innovation System,” (ITIF, March 2019), https://itif.org/publications/2019/03/04/bayh-dole-acts-vital-importance-us-life-sciences-innovation-system/.

[14] Statement of Senator Birch Bayh to the National Institutes of Health (May 24, 2004), https://www.ott.nih.gov/sites/default/files/documents/2004NorvirMtg/2004NorvirMtg.pdf.

[15] Thomas, “March-In Rights Under the Bayh-Dole Act,” 10.

[16] Birch Bayh, “Statement of Birch Bayh to the National Institutes of Health,” May 25, 2014, http://www.essentialinventions.org/drug/nih05252004/birchbayh.pdf.

[17] Birch Bayh and Bob Dole, “Our Law Helps Patients Get New Drugs Sooner,” The Washington Post, April 11, 2002, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/opinions/2002/04/11/our-law-helps-patients-get-new-drugs-sooner/d814d22a-6e63-4f06-8da3-d9698552fa24/.

[18] Stephen Ezell, “Comments to the National Institutes of Health on “Maximizing NIH’s Levers to Catalyze Technology Transfer” (ITIF, August 2023), https://itif.org/publications/2023/08/18/maximizing-nih-levers-to-catalyze-technology-transfer/.

[19] National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), “Return on Investment Initiative: Draft Green Paper” (NIST, December 2018), 30, https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/SpecialPublications/NIST.SP.1234.pdf.

[20] Ibid., 30.

[21] National Institutes of Health (NIH), “NIH Intramural Research Program Access Planning Policy,” Notice NOT-OD-25-062, (NIH, January 10, 2025), https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-25-062.html.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ibid.

[24] National Institutes of Health, “NIH News Release Rescinding Reasonable Pricing Clause,” news release, April 11, 1995, https://www.ott.nih.gov/sites/default/files/documents/pdfs/NIH-Notice-Rescinding-Reasonable-Pricing-Clause.pdf.

[25] Joe Allen, “Compulsory Licensing for Medicare Drugs—Another Bad Idea from Capitol Hill.,” IP Watchdog, August 23, 2018, https://ipwatchdog.com/2018/08/23/compulsory-licensing-medicare-drugs-bad-idea/id=100608/.

[26] National Institutes of Health, “OTT Statistics,” accessed January 13, 2019, https://www.ott.nih.gov/reportsstats/ott-statistics.

[27] National Institutes of Health, “NIH News Release Rescinding Reasonable Pricing Clause.”

[28] Stephen Ezell, “How the Prescription Drug User Fee Act Supports Life-Sciences Innovation and Speeds Cures” (ITIF, February 2017), https://www2.itif.org/2017-pdufa-life-sciences-innovation.pdf; PhMRA, “The Prescription Drug User Fee Act: Promoting the timely availability of safe and effective medicines to patients,” https://phrma.org/policy-issues/research-development/pdufa.

[29] National Institute of Health, “Supplemental Guidance to the 2024 NIH Grants Policy Statement: Indirect Cost Rates,” Notice Number: NOT-OD-25-068, February 7, 2025, https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-25-068.html#_ftnref2.

[30] Heidi Ledford, “Indirect costs: Keeping the lights on,” Nature, December 23, 2014, https://www.nature.com/news/indirect-costs-keeping-the-lights-on-1.16376.

[31] National Institute of Health, “Supplemental Guidance to the 2024 NIH Grants Policy Statement: Indirect Cost Rates”; Alexandra Graddy-Reed et al., “The Distribution of Indirect Cost Recovery in Academic Research” Science and Public Policy Volume 48, Issue 3 (June 2021): 364–386, https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scab004.

[32] The State Council, The People’s Republic of China, “China's science foundation ups research budget to 33b yuan,” news release, March 25, 2022, https://english.www.gov.cn/news/topnews/202203/25/content_WS623d8d30c6d02e5335328459.html.

[33] Daniel Castro, “Trump Has Opportunity to Usher In a Golden Age of Transportation By Embracing Automation,” Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, January 3, 2025, https://itif.org/publications/2025/01/03/trump-has-opportunity-to-usher-in-golden-age-of-transportation/.

[34] Daniel Castro, “Trump Has Opportunity to Usher In a Golden Age of Transportation By Embracing Automation,” Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, January 3, 2025, https://itif.org/publications/2025/01/03/trump-has-opportunity-to-usher-in-golden-age-of-transportation/.

[35] Joe Allen, “The Department of Energy’s Technology Giveaway,” IP Watchdog, February 19, 2025, https://ipwatchdog.com/2025/02/19/department-energys-technology-giveaway/id=186280/.

[36] Stephen Ezell, “How Innovative Is China in Nuclear Power?” (ITIF, June 2024), https://itif.org/publications/2024/06/17/how-innovative-is-china-in-nuclear-power/; Sha Hua, “Atomic Power Is In Again—and China Has the Edge,” The Wall Street Journal, December 7, 2023, https://www.wsj.com/world/china/atomic-power-is-in-againand-china-has-the-edge-5f8a8b84; Jennifer Hiller and Sha Hua, “China Outspends the U.S. on Fusion in the Race for Energy’s Holy Grail,” The Wall Street Journal, July 8, 2024, https://www.wsj.com/world/china/china-us-fusion-race-4452d3be.

[37] Joe Allen, “More DOE Bureaucracy Equals Less Innovation,” IP Watchdog, May 15, 2023, https://ipwatchdog.com/2023/05/15/doe-bureaucracy-equals-less-innovation/id=160837/.

[38] Stephen Ezell, “The “Invent Here, Make Here” Act Should Fully Advance, Not Partially Impede, Bayh-Dole’s Mission,” Innovation Files, May 15, 2024, https://itif.org/publications/2024/05/15/invent-here-make-here-act-should-fully-advance-bayh-dole/.

[39] Association of University Technology Managers (AUTM), “U.S. Manufacturing Waiver Survey,” (AUTM, May 2023), https://autm.net/AUTM/media/Events/Images/AUTM-US-Manufacturing-Waiver-Survey-Results_VF.pdf.

[40] Aadil Brar, “China's Raw Material Control Could Strangle US Defense Industry—Ex-Official,” Newsweek, February 16, 2024, https://www.newsweek.com/china-raw-material-us-defense-industry-ex-official-1870125.

[41] Robert D. Atkinson, “Why the United States Needs a National Advanced Industry and Technology Agency” (ITIF, June 2021), https://itif.org/publications/2021/06/17/why-united-states-needs-national-advanced-industry-and-technology-agency/.

[42] Stephen Ezell, “The CHIPS Program Office Needs to Think Like Economic Developers, Not Bankers,” Innovation Files, February 1, 2024, https://itif.org/publications/2024/02/01/the-chips-program-office-needs-to-think-like-economic-developers-not-bankers/.

[43] Yuka Hayashi, “Eager for Economic Wins, Biden to Announce Billions for Advanced Chips,” The Wall Street Journal, January 27, 2024, https://www.wsj.com/politics/policy/eager-for-economic-wins-biden-to-announce-billions-for-advanced-chips-7e341e30.

[44] Ibid.

[45] The Trump White House, “Fact Sheet: President Donald J. Trump Establishes the United States Investment Accelerator,” news release, March 31, 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/fact-sheets/2025/03/fact-sheet-president-donald-j-trump-establishes-the-united-states-investment-accelerator/.

Related

February 6, 2024

Comments to the NIST Regarding the Draft Interagency Guidance Framework for Considering the Exercise of March-In Rights

March 4, 2019