The EU Has Been Taking Advantage of America’s Effort to Combat Chinese Economic Mercantilism

In his first term, President Trump called out and took action against systematic Chinese innovation mercantilism, as ITIF had long argued America must. Yet many critics accused Trump of starting a trade war—and in the EU, many disavowed the administration’s actions, calling it the “U.S.-China trade war.” It was a reality-defying attempt to stake out a neutral position, even though Chinese techno-economic aggression was and is a threat to the free world—and in some ways a bigger threat to the EU economy than to the U.S. economy.

Indeed, rather than thank the United States for serving as the tip of the spear by sacrificing our economic resources to push back against a common adversary, the prevailing view in European policy circles was that the EU should take advantage of the situation. For example, a leading EU think tank, Bruegel, published a piece in 2018 titled, “How could Europe benefit from a U.S.-China trade war?” The piece suggested that while the United States tangled with China alone, there was an opening for Europe to profit by positioning itself as a friendlier trading partner. As Bruegel argued, “the trade war … offers Europe a far larger opportunity. Under pressure from the U.S., Beijing is set to be more open to make new allies.” How would the EU like it if a major U.S. think tank argued, “the Russian invasion of Ukraine offers the United States a far larger opportunity”?

Bruegel went on to stipulate that China does not follow the WTO rules. Moreover, it rightly noted that “Beijing can’t afford having Japan, the U.S. and the EU form a united front as they recently did with a declaration on forced technology transfer that was clearly targeted at China.” But then it proceeded to argue that the EU swoop in and selfishly take advantage of China’s closing its market to U.S. firms.

One Spanish think tank went so far as to say Trump’s actions present “opportunities for the strengthening of relations between the EU and China,” including a military alliance! In May 2017, German Chancellor Merkel hosted a red carpet ceremony for Xi Jinping where she said that it was a “good opportunity” to expand relations between Germany and China.

European leaders knew that if they joined with the United States, then China would punish them just as it punished the United States with tariffs, direct import bans, and bogus investigations into U.S. companies. So, the EU took the low road: betraying a core ally to curry favor and drive exports to China.

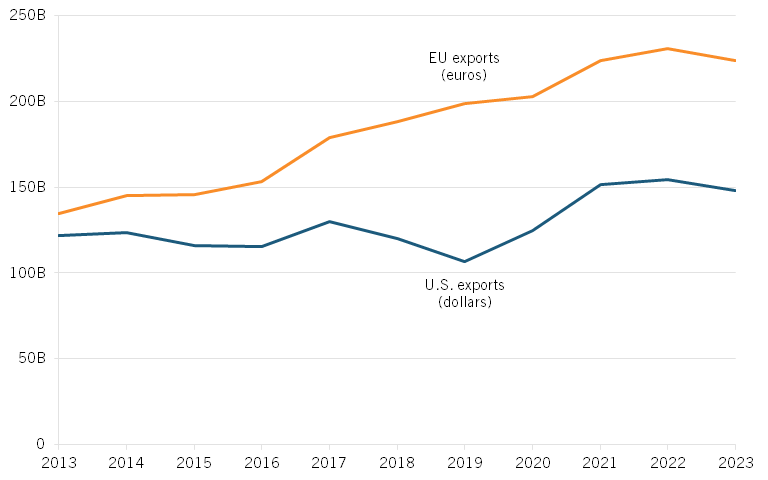

And it worked. We can see that in the change in exports to China from the United States and the EU, respectively. Though it started in a similar place to the United States just a decade ago, the EU’s exports to China have since diverged from U.S. exports to China, growing by 66 percent while U.S. exports have grown just 21 percent. (See figure 1.)

Figure 1: EU exports to China (in euros) versus U.S. exports to China (in dollars)

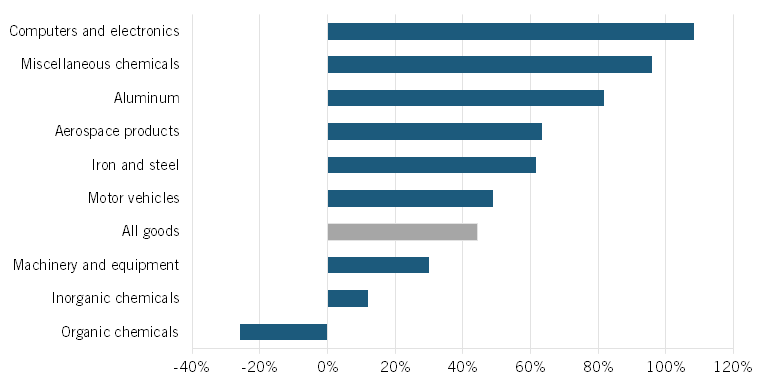

But even more concerning is how the EU has increased exports of goods in key advanced industries. EU exports of strategically important products such as machinery, electronics, semiconductors, and aerospace equipment have dramatically increased over the past decade, demonstrating an increased reliance on China as a market. Figure 2 shows the change in EU exports to China in select advanced industries from 2013 to 2023, less the change in U.S. exports to China in the same period. In most cases, exports from the EU grew at a far greater rate than exports from the United States. In the motor vehicle industry, exports of U.S. cars dropped by 21 percent, while EU exports grew by 28 percent. In computer and electronics, a broad category that includes semiconductors and computers, U.S. exports grew by just 2 percent while EU exports rocketed up by 111 percent.

China more or less banned Boeing from its domestic market in retaliation for Trump’s actions, and as a result Boeing has not sold a plane there since 2017. Meanwhile, rather than stand with America and refuse to sell jets to China, the EU swooped in and took those sales. We see the same pattern in other industries, including auto parts and machinery and equipment.

Figure 2: Change in EU exports to China, relative to change in U.S. exports, 2013–2023

With friends like these, who needs enemies? But 2017 is not 2025. In recent years, at least some in Europe have cast off their rose-colored glasses and come to better understand the core threat China poses to EU advanced industries. We can hope that this time around EU leaders will not be blinded by “Trump derangement syndrome” or seduced by the siren song from Beijing. Regardless, the Trump administration will need to make it clear to European officials that if the EU and its members want to maintain close relationships with the United States, including militarily, then they will need to stop taking advantage of the U.S.-China trade conflict and start taking a more active role as a true ally.