Comments to the Departments of Justice and Transportation Regarding Competition in Air Transportation

Common Critique of Airline Consolidation Is Wrong. 2

Competition on Individual Routes Has Gone Up, Not Down. 2

Discount Carriers Have Taken an Increasing Share of Passengers Away From the Big Three. 4

Air Fares Have Continued to Decline. 4

Capacity Changes Are Harder to Assess, But Consumers Have Not Seen Any Increase in Air Fares 5

The Quality of Airline Service Has Declined, But Not Because of Consolidation. 6

Two Misunderstood Elements of Service Quality 6

Introduction

Nowhere is the gap between punditry and reality greater than on the subject of U.S. airline consolidation and competition.

Between 2008 and 2014, the Department of Justice (DOJ) approved a series of mergers that reduced the number of large U.S. airlines from eight to four, as Delta Air Lines acquired Northwest Airlines, United Airlines merged with Continental Airlines, American Airlines combined with US Airways, and Southwest Airlines acquired AirTran Airways. U.S. carriers argued at the time—and DOJ ultimately agreed—that the mergers would combine route networks that were largely non-overlapping and thus not lessen competition.

DOJ called it right: The mergers have not harmed competition or consumers. Moreover, by combining complementary networks and fleets, the mergers allowed U.S. carriers to return to profitability following the one-two punch of 9/11 and the 2008 financial crisis. As a result, carriers have been able to offer broader, overlapping route maps for flyers, expand their global networks, and provide significant benefits to airline workers.

Despite the dearth of supporting evidence, a group of pundits and policymakers have espoused a contrary narrative that has gained unwarranted traction. According to this populist narrative, the mergers reduced the robust competition that American travelers had previously enjoyed, allowing the remaining “Big Four” carriers to cut capacity, decrease service quality and raise prices.

One disseminator of this false narrative is Columbia law professor Tim Wu, who wrote The Curse of Bigness and was an architect of President Biden’s controversial antitrust policy. In a 2023 essay in the New York Times that cited no statistics, Wu argued that the history of modern airline mergers demonstrates one thing: “The bigger airlines get, the worse they become. The prices get higher, the seats smaller, the service ever snarkier.”[1]

Berkeley professor Robert Reich has made similar claims:

[A]ntitrust laws have been relaxed for corporations with significant market power, such as … big airlines… As a result, Americans pay more for … airline tickets … than the citizens of any other advanced nation.[2]

Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-MA), the most vocal congressional critic of corporate mergers, generally, has echoed these assertions. In a 2022 letter to Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg, she wrote that “Airline industry competitiveness is in free fall” as the result of “a series of airline mega-mergers that have reduced service quality and increased fares.”[3]

Common Critique of Airline Consolidation Is Wrong

The pundits and their congressional followers could not be more wrong. Three economic indicators, all based on publicly available data collected by the Department of Transportation (DOT), tell the real story:

▪ The number of competitors on individual routes has gone up, not down.

▪ Discount carriers have taken a growing share of passengers away from the Big Three legacy carriers (American, Delta and United) and now carry nearly half of all domestic passengers.

▪ Air fares (adjusted for inflation) have continued the 45-year decline that began with airline deregulation.

The impact of any changes in capacity following a merger is harder to assess, but the continued decline in fares is the best indicator that consumers were not harmed.

The (perceived) quality of airline service has gone down but not because of consolidation; rather, deregulation has allowed carriers to give passengers what they consistently show a preference for: lower fares at the expense of amenities.

Competition on Individual Routes Has Gone Up, Not Down

Critics of airline consolidation assert, as if it were a smoking gun, that “the “Big Four” carriers [American, Delta, United and Southwest] control 80 percent of the domestic airline market.” While this statistic is roughly accurate (the four carriers transported 76 percent of domestic passengers in the first half of 2024), it is highly misleading for two reasons.

First, statistics on nationwide market share say little about the state of airline competition because airlines compete on individual routes. (The media’s preoccupation with nationwide market share is the single biggest source of misleading claims about airline competition.) To understand the effect of recent mergers on competition, one must look at data at the individual route level—or what DOT refers to as city-pair markets.

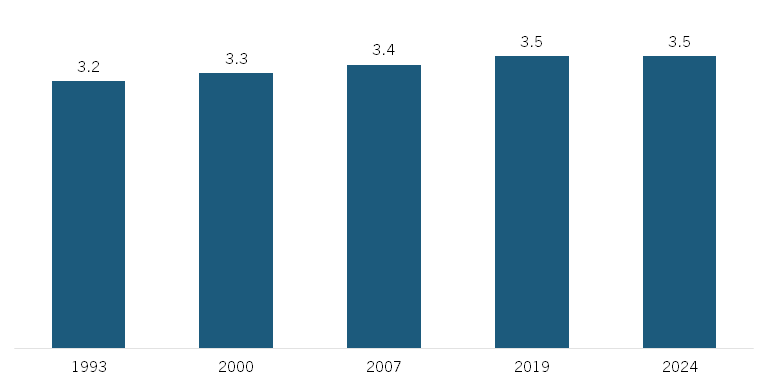

An analysis of DOT data conducted by Compass Lexecon, an economic consulting firm, shows that the average number of competitors in domestic U.S. city-pair markets has increased steadily albeit marginally over the last three decades.[4]

Figure 1: Average number of competitors in U.S. city-pair markets

(Note that while Compass Lexecon typically works for airline clients, its analysis is used in litigation and thus must withstand rigorous scrutiny. Compass Lexecon economists routinely publish their analyses in peer-reviewed academic journals.)

These figures include carriers with a market share of at least 5 percent, which is the DOT standard for what constitutes an effective competitor. If one limits the analysis to carriers with at least 10 percent of the local market, the number of competitors per route is somewhat smaller but the trend is the same.

Second, the “Big Four” assertion ignores the distinction between the “Big Three” legacy hub-and-spoke carriers (American, Delta and United) and Southwest Airlines, a point-to-point low-cost carrier (LCC). In the decades following airline deregulation in 1978, Southwest was the major driver of competition, because when it entered a market—or even threatened entry—legacy carriers reduced their fares by 30 percent on average to remain competitive—what’s known as “the Southwest Effect.”[5] Southwest’s success gave rise to other LCCs such as JetBlue Airways and Virgin America, and eventually to ultra-low-cost carriers (ULCCs) such as Frontier Airlines, Spirit Airlines and Allegiant Air.

Contrary to what consolidation critics assert or imply, Southwest has not become a Big-Three lookalike. According to DOT data reported by Compass Lexecon, Southwest’s cost per available seat mile, or CASM, is substantially below that of the Big Three network carriers, as is its domestic price per mile, or “yield.”[6] Although Southwest is adapting its no-frills, economy-seat-only business model in response to business challenges and a changing customer demographic, there is no reason to think it will not remain a competitive maverick that imposes significant pricing discipline on the legacy carriers.

Discount Carriers Have Taken an Increasing Share of Passengers Away From the Big Three

In the last 20+ years, discount carriers (including Southwest) have grown at rates several times those of the Big Three. ULCCs, whose ultra-low fares stimulate demand on the part of people who could not otherwise afford to fly, have seen the fastest growth—from 2 percent of the market in 2000 to 14 percent in 2024.[7] LCCs such as JetBlue and Alaska Airlines, whose business model combines discount fares with some of the amenities of legacy-carrier service, have also seen robust growth.

Notably, 2021 saw the launch of two discount carriers: Breeze Airways, an LCC owned by JetBlue founder David Neeleman, and Avelo Airlines, a ULCC operated by former Allegiant chief executive Andrew Levy. Both carriers fly to underutilized airports in smaller cities such as New Haven, CN, and Wilmington, SC. Less than four years in, Breeze and Avelo are serving 66 and 54 U.S. airports, respectively, and both carriers are approaching profitability.[8]

As a result of this growth, discount carriers (including Southwest) now carry nearly half of all U.S. domestic passengers—up from 24 percent in 2000. Conversely, the legacy hub-and-spoke carriers have seen their collective market share drop from 73 percent in 2000 (and 85 percent in 1990) to only 52 percent in 2024.[9] This is a remarkable shift in the competitive landscape.

No less important, fully 90 percent of U.S. domestic passengers now fly on routes that are served by at least one LCC or ULCC.[10] (Half of all domestic passengers fly on routes served by at least one ULCC.) Because of the fare discipline that discount carriers, generally—not just Southwest—impose, these passengers enjoy lower fares even if they choose to fly on a non-discount carrier.[11]

To be sure, a number of discount carriers face significant business challenges. In part, this reflects the fact that full-service legacy carriers, having lost many of their business passengers to online video technology (why fly to a corporate meeting when you can “attend” virtually?), are actively courting leisure travelers. In response, ULCCs are beginning to offer legacy-style options (e.g., expanded legroom, reserved middle seat) even as legacy carriers offer unbundled fares—a pricing option that ULCCs developed to reach potential travelers at the “bottom of the demand curve.” While the outcome of this dynamic contest between (and among) discount and legacy carriers is far from clear, it is almost certain to benefit consumers.

Air Fares Have Continued to Decline

Air fares are the ultimate measure of competition. In the decades following airline deregulation, demand for air travel grew by 4 percent a year (compared to a 2.4 percent average annual growth in the economy overall), and fares dropped steadily. Fares today are 30–55 percent lower in real terms than they were in 1978.[12] As a result, commercial air travel, which was considered an elite activity prior to deregulation, is now a routine experience for most adult Americans.

Air fares spiked temporarily in 2022, as the result of a unique set of conditions, including COVID-related factors (significant pent-up demand and an acute pilot shortage that grounded hundreds of planes) and a Ukraine-related surge in oil prices (fuel is a key driver of airline costs). However, by the end of October 2024, air fares were 20 percent below their 2019 (pre-COVID) level, which at the time had marked a historic low.[13]

The democratization of air travel that deregulation made possible has continued apace with the growth of ULCCs and the price response they elicit from legacy and other discount carriers. According to Compass Lexecon’s analysis of DOT data, fares at the bottom end of the fare distribution (the lowest 10 percent) have fallen by nearly half over just the last decade—a larger drop than for any other part of the fare distribution.[14]

Capacity Changes Are Harder to Assess, But Consumers Have Not Seen Any Increase in Air Fares

In its 2021 complaint against the American-JetBlue Northeast Alliance, DOJ said that each significant legacy airline merger in recent years had been followed by substantial reductions in capacity.[15] In the report it submitted for this proceeding, Compass Lexecon takes direct issue with the DOJ assertion:

[I]ndustry consolidation did not precipitate network carrier capacity reductions as some airline merger critics have wrongly alleged. The vast majority of underutilized capacity removed by the network carriers pre-dated their respective mergers, as shown in Figure 13 below… [footnotes and figure omitted].[16]

The impact of changes in capacity following a merger is tricky to assess. Without wading into the analytic disagreement between DOJ and Compass Lexecon, one can make several basic observations.

The most obvious one is that fares did not go up following the mergers, which is the main reason to worry about capacity reductions. Carriers can reduce capacity for a variety of reasons other than to try to raise fares—e.g., to remove money-losing or low net revenue flights. Whatever the explanation, the fact that fares did not increase following the mergers indicates that consumers were not harmed.

Second, one reason carriers cut capacity on some routes is to expand it on other, more lucrative ones, and that appears to have happened here. For example, Delta eliminated Cincinnati and Memphis as secondary hubs following its 2008 merger with Northwest. At the same time, Delta strengthened its presence at Salt Lake City and priority cities like Raleigh-Durham, and it built a new hub at Seattle, competing squarely with Alaska Airlines. During the post-merger period, American, Delta and United all expanded aggressively in one another’s hub cities.

Third, although the legacy carriers’ “de-hubbing” decisions resulted in significant cuts in service to affected cities, discount carriers added new service in response. For example, Southwest, along with ULCCs Allegiant and Frontier backfilled empty gates at Cincinnati, and other former hubs (Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Memphis and St. Louis) saw a similar response.[17] This may help explain why fares did not go up.

Finally, small communities, which are served largely by regional airlines on behalf of the full-service legacy carriers, have benefited from consolidation because they contribute traffic that supports the carriers’ hub-and-spoke system. According to Compass Lexecon, the legacy carriers’ have increased their capacity (daily seats) to and from small communities by 29 percent over the last decade.[18]

The Quality of Airline Service Has Declined, But Not Because of Consolidation

Properly defined, airline service has improved in many ways in recent decades, including network breadth, service frequency, nonstop offerings, and safety performance. Other improvements include amenities like in-seat power, WiFi and upgraded lounges.

However, by the more common measures—seat width, number of empty middle seats, availability of “free” amenities–service quality has gone down. Late-night comedians routinely make poor airline service the butt of their jokes, and at a recent congressional hearing, a senator asked an airline executive if he had any idea how unpleasant an experience it was to fly.

The decline in (perceived) service quality is real but it is the result of airline deregulation, not consolidation, and it reflects consumer choice. Overall, airlines are giving passengers what they consistently show a preference for: lower fares at the expense of amenities.

To elaborate, flying is less enjoyable largely because of the increase in load factor: planes that typically flew half empty prior to 1978 now operate 80–85 percent full on average. Deregulation also marked the end of piano bars, prime rib served on fine china, and flight attendants wearing skimpy uniforms—all ways in which the regulated airlines competed on quality because they were prohibited from competing on price. Finally, deregulation paved the way for ULCCs, whose business model generally calls for the elimination of amenities.

It is not much of an overstatement to say that the back of the plane is brought to you by airline deregulation. Air carriers can offer cheap economy fares because they serve to fill seats that once flew empty. Travelers who want the comforts of pre-deregulation service can always fly business class, and they will be paying about what they would have paid absent deregulation. While some flyers select that option, most choose the combination of low fares and lean service.

Two Misunderstood Elements of Service Quality

Ancillary Fees

Two other elements of service quality broadly defined are worth noting. The first is ancillary fees. Spirit introduced them as a way to lower its base (unbundled) fare and thereby make travel affordable to those at the bottom of the demand curve. (The practice began when Sprit discovered that 30 percent of its passengers did not check a bag. Spirit lowered its base fare by $20 and imposed a $20 bag-check fee. No passengers were worse off, and passengers who did not check their bags saved $20 on their fare. Spirit extended the practice to other services that not all passengers took advantage of—lowering the base fare while imposing a comparable but optional service fee.)[19] Other discount and legacy carriers followed suit.

Economists love ancillary fees (unbundled fares) because they are pro-consumer, and DOJ has lauded Spirit for introducing them. While President Biden made the airline industry Exhibit A in his campaign against “junk fees,” he apparently had not read DOJ’s complaint to block the Spirit-JetBlue merger, which repeatedly applauded Spirit’s disruptive influence on pricing as evidenced by its introduction of unbundled fares.

In short, the growing use of ancillary fees ought not be seen as a way airlines are reducing service quality (or raising the cost of travel). It should be seen as a way airlines are giving travelers additional choice—namely, the option to fly at a bare-bones price.

Flight Delays

The second element of service quality worthy of comment is flight delays. Flight delays and cancellations genuinely reduce the quality of the travel experience, and they impose significant costs on travelers and carriers alike. According to a study done for the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) by a consortium of universities, in 2007, the direct cost of U.S. flight delays was $32.9 billion, including $8.3 billion in increased airline expenses (e.g., crew, fuel and maintenance); $16.7 billion in passenger time lost due to schedule buffer, delayed flights, flight cancellations and missed connections; and $3.9 billion in lost demand (i.e., the welfare loss incurred by passengers who avoided air travel as a result of delays).[20]

This is a complex topic on which much has been written (including by this author).[21] Simply stated, air traffic control is a 24/7, capital-intensive, high-tech service “business” trapped in a regulatory agency (FAA) that is constrained by federal procurement and budget rules, burdened by a flawed financing system, and micro-managed by Congress and the Office of Management and Budget. To be sure, air traffic control must be regulated for safety. But air traffic control is not inherently governmental, and the current approaches to governance and financing of the system are directly to blame for the problems we observe, including flight delays, antiquated technology, deteriorating facilities, and (more recently) a shortage of air traffic controllers.[22]

The debate over whether and how to reform the U.S. air traffic control system will hopefully continue. The point here is that the federal government operates the U.S. air traffic control system, and it, not the airline industry—and certainly not airline consolidation—is responsible for the flight delays resulting from the system’s shortcomings.

Conclusion

Competition in the U.S. aviation sector is alive and well. Airline deregulation unleashed enormous pent-up demand for air travel, as U.S. carriers (most of whom, along with labor, had opposed deregulation in favor of the comfortable status quo) responded with low fares and appealing service options. Deregulation also positioned the U.S. government to negotiate with foreign governments for “open skies” agreements, and U.S. carriers, having been battle-tested at home, were poised to compete internationally.

DOJ was a strong advocate for airline deregulation (John Shenefield, who died last month, led the Antitrust Division from 1977–1979 and helped persuade a skeptical Congress), and DOJ’s steadfast concern with preserving competition has been key to the success of deregulation. Likewise, DOT has been a staunch advocate for airline competition, including through its oversight of the FAA.

Deregulation has been a chaotic process, entailing dozens of bankruptcies and mergers. The through line has been robust competition, largely as a result Southwest and other discount carriers, leading to ever lower fares and greater choice for travelers. The 2008-2014 mergers that pundits decry did nothing to slow that beneficial process and, if anything, may have helped to propel it.

The weak link in the chain has always been aviation infrastructure, as evidenced by chronic congestion and flight delays.[23] On the eve of deregulation, Alfred Kahn, the charismatic chair of the Civil Aeronautics Board, warned the FAA that the demand about to be unleashed would put new pressure on the country’s runway infrastructure. To no avail, Kahn encouraged the FAA to put a price on scarce runway infrastructure—what amounts to congestion pricing. Two decades later, Kahn became a champion for “corporatization” of the air traffic control system, to allow for more efficient use of scarce airways.

More recently, with controller shortages and the FAA’s failure to widely deploy technology to prevent runway incursions, the shortcomings of the air traffic control system have come to pose a threat to aviation safety, not just efficiency.

To be sure, the federal government should never let up on the antitrust “pedal” when it comes to aviation. Competition is critical. However, it is past time to give the same attention to aviation infrastructure. Fred Kahn, a self-described trustbuster, would agree.

Thank you for your consideration.

Endnotes

[1]. Tim Wu, “The Bigger Airlines Get, the Worse They Become,” Guest Essay, New York Times, December 4, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/12/04/opinion/jetblue-spirit-airlines-merger.html.

[2]. Robert Reich, “Opinion: Why We Must End Upward Pre-Distributions to the Rich,” The Christian Science Monitor, September 30, 2015, https://www.csmonitor.com/Business/Robert-Reich/2015/0930/Opinion-Why-we-must-end-upward-pre-distrubtions-to-the-rich.

[3]. Letter from Senator Elizabeth Warren to Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg, September 15, 2022, https://beatofhawaii.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Elizabeth-Warren-Comments-on-Meger.pdf.

[4]. See Darin Lee, Erin Secatore, Ethan Singer, and Eric Amel, Compass Lexecon, “Comments in Response to the Joint Request for Information on Competition in Air Transportation, by the Departments of Justice and Transportation,” January 3, 2025 (hereafter the “Compass Lexecon Report”), pp. 7-8. Here and elsewhere, Compass Lexecon statistics for 2024 are based on data for the first half of the year.

[5]. Clifford Winston, Jia Yan and Associates, Revitalizing a Nation: Competition and Innovation in the U.S. Transportation System, Brookings Institution Press, 2024, Chapter 7. See also Clifford Winston, “Airline Competition, Regulatory Policy, and Constructive Policy Improvements,” Statement to the U.S. Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation, February 9, 2023, https://www.commerce.senate.gov/2023/2/executive-session.

[6]. Compass Lexecon Report, op. cit., pp. 21-22.

[7]. Compass Lexecon Report, op. cit., Figure 2.

[8]. Niraj Chokshi, “Coming to a Tiny Airport Near You: New Airlines,” New York Times, December 25, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/12/25/business/avelo-breeze-small-airports.html.

[9]. Compass Lexecon Report, op. cit., Figure 2.

[10]. Compass Lexecon Report, op. cit., p. 7.

[11]. Brookings’ Clifford Winston and two associates estimated the impact on fares if a European LCC were to enter all U.S. domestic routes that were not served by a U.S. LCC or ULCC. The effect of introducing this hypothetical service (“cabotage”), which U.S. law currently prohibits, was surprisingly modest because so much of the U.S. market already enjoys low-cost service. Clifford Winston, Jia Yan and Associates, Revitalizing a Nation, op. cit., Chapter 7.

[12]. Compass Lexecon estimates that fares have dropped by 55 percent in real terms since deregulation. See Compass Lexecon Report, op. cit., p. 46. The lower-range estimate is based on an analysis by Clifford Winston and two associates which concluded that Southwest Airlines’ entry in U.S. markets reduced fares by 30 percent from 1994–2014. See footnote 5 above. It is worth noting that Winston himself cited (an earlier iteration of) the higher-range estimate, which he attributed to Airlines for America, in 2023 congressional testimony. See Winston, Statement to the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation, op. cit., p. 1.

[13]. Compass Lexecon Report, op. cit., pp. 46-47.

[14]. Compass Lexecon Report, op. cit., p. 49.

[15]. Complaint, United States of America, et al. v. American Airlines Group Inc. and JetBlue Airways Corporation, September 21, 2021, p. 12, https://www.justice.gov/opa/press-release/file/1434621/dl.

[16]. Compass Lexecon Report, op. cit., p. 30.

[17]. Winston, Jia Yan and Associates, Revitalizing a Nation, op cit., Chapter 7.

[18]. Compass Lexecon Report, op. cit., p. 35.

[19]. Ben Baldanza, “Airline Fees Are Not ‘June Fees’ – That Term Poisons the Debate,” Forbes, July 13, 2023, https://www.forbes.com/sites/benbaldanza/2023/07/12/airline-fees-are-not-junk-fees---that-term-poisons-the-debate/.

[20]. Michael Ball, et al., “Total Delay Impact Study: A Comprehensive Assessment of the Costs and Impacts of Flight Delay in the United States” (October 2010), available at: http://www.isr.umd.edu/NEXTOR/pubs/TDI_Report_Final_10_18_10_V3.pdf.

[21]. See, for example, Dorothy Robyn with Kevin Neels, “Air Support: Creating a Safer and More Reliable Air Traffic Control System,” Hamilton Project, Brookings Institution, July 2008, https://www.hamiltonproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Air_Support-_Creating_a_Safer_and_More_Reliable_Air_Traffic_Control_System.pdf.

[22]. “Options for FAA Air Traffic Control Reform,” Statement of Dorothy Robyn before the House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure, Subcommittee on Aviation, March 24, 2015, https://transportation.house.gov/uploadedfiles/2015-03-24-robyn.pdf.

[23]. Dorothy Robyn, “The Unfinished Business of Transportation Deregulation,” TR News, May-June 2018, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/POV-Robyn.pdf. TR News is a publication of the National Academy of Science’s Transportation Research Board.

Editors’ Recommendations

December 15, 2023

US Airline Consolidation Has Not Harmed Competition or Consumers

February 14, 2019