Corporate Concentration Is Good for Productivity and Wages

Despite claims by anticorporate neo-Brandeisians, corporate concentration appears positively correlated with higher productivity and wages. So, the push to break up large companies is antiworker and anti-middle class.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Key Takeaways

Contents

Rebutting The Argument That Concentration Hurts Productivity and Wages 5

Concentration and Labor Productivity 8

Concentration and Labor Compensation. 12

Implications and Policy Recommendations 18

Introduction

In recent years, a growing group of neo-Brandeisian, anti-big business proponents have argued that rising concentration is causing a series of economic ills in order to advocate for policy that will weaken and shrink large businesses. These advocates assert that concentration is causing problems ranging from poor job reallocation to declining new business formation. More recently, the neo-Brandeisians and their allies have doubled down on the link between concentration and productivity, arguing that concentration has negatively affected productivity growth in the economy.[1] Similarly, they have argued that rising concentration has depressed wages. However, many of these assertions about the link between concentration and productivity or wages are based on weak or nonexistent evidence. Nevertheless, the calls for the breakup of large businesses continue unabated.

Rising concentration can also boost productivity if firms are gaining market share because of more-productive practices, especially through economies of scale and other efficiencies.

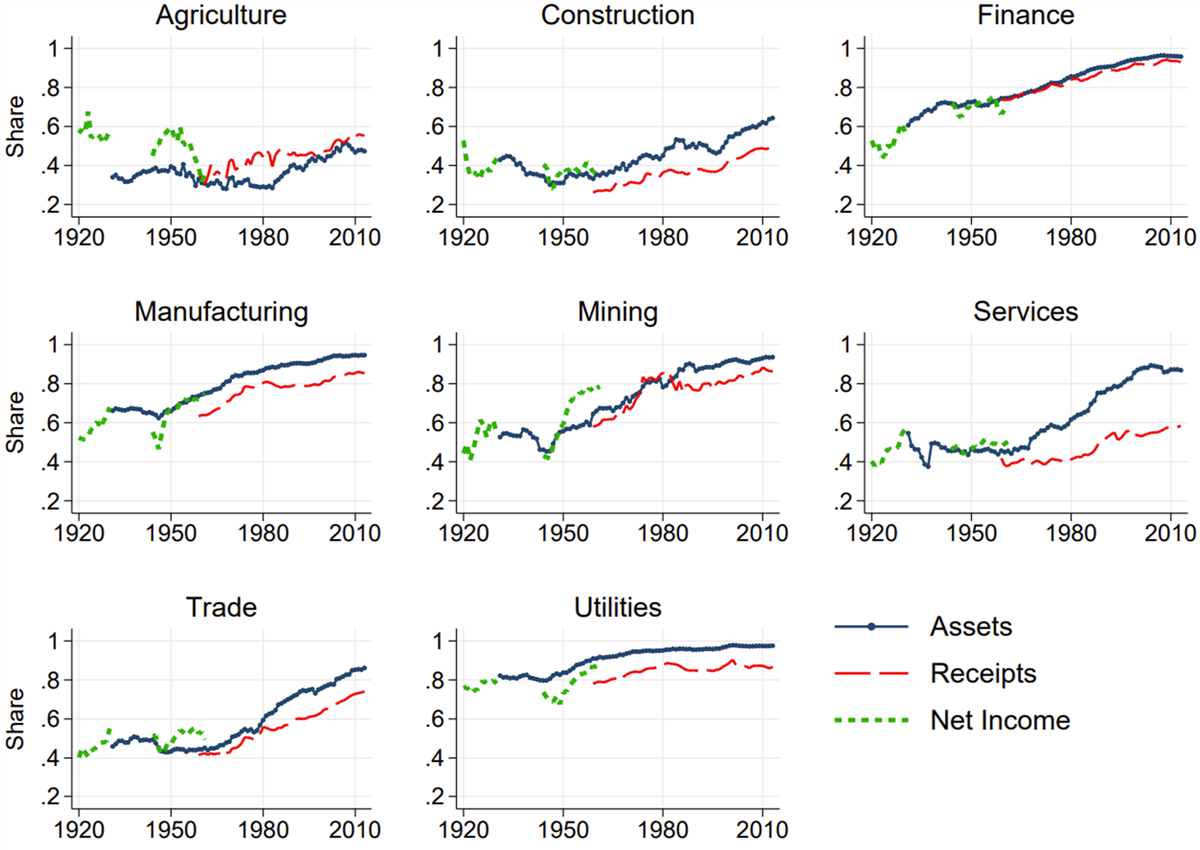

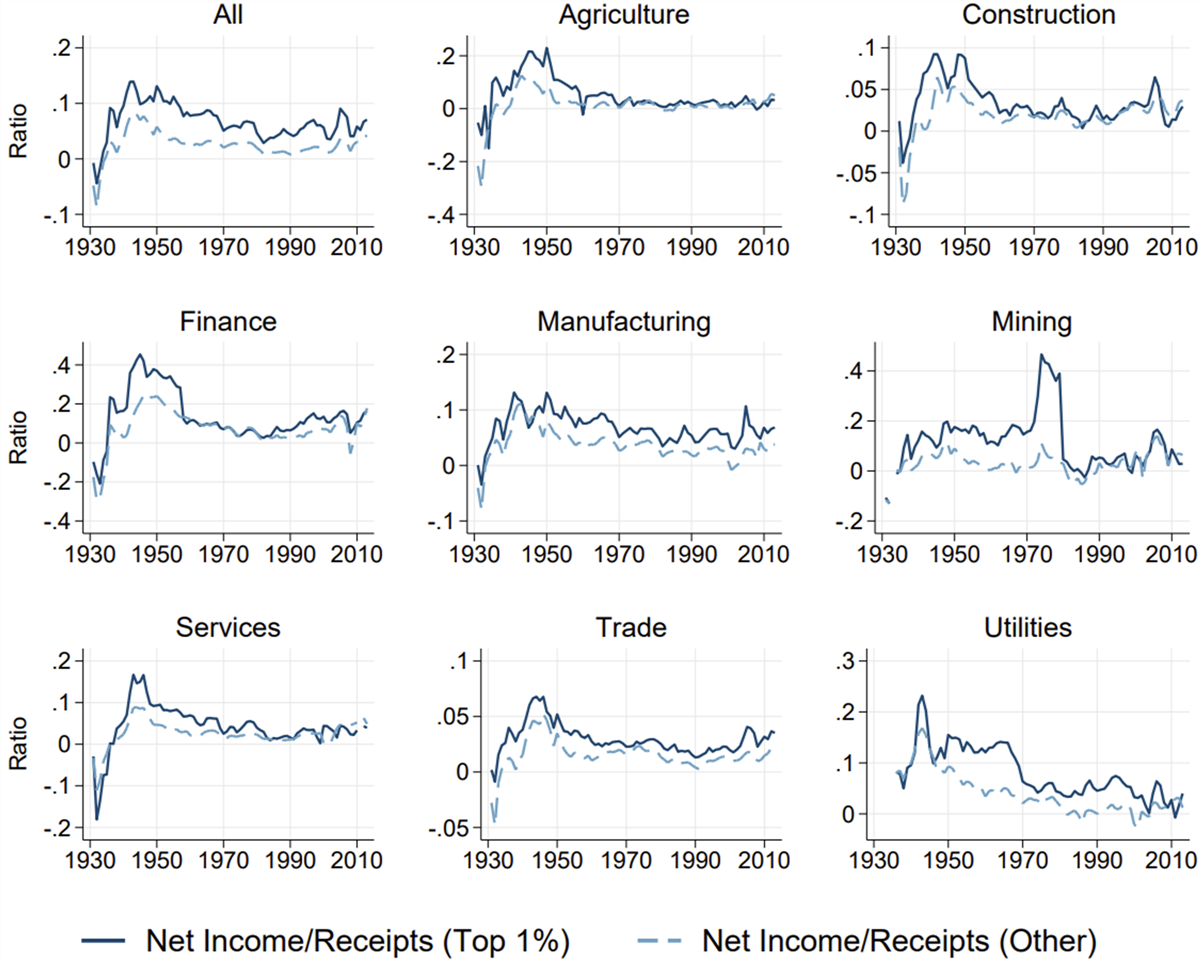

In fact, the effect of concentration on productivity and wages is theoretically ambiguous. Rising concentration can negatively impact productivity if firms become “fat and happy” and reduce investment. However, it can also boost productivity if firms are gaining market share because of more-productive practices, especially through economies of scale and other efficiencies. Similarly, rising concentration could hurt wages if firms use their rising labor market power to depress wages, although that is extremely difficult to do because, unlike some product markets, virtually all labor markets are highly competitive. On the other hand, concentration can also increase wages. This is because concentration enables firms to boost productivity and, in turn, raise wages—although much of the benefits of productivity are, in fact, passed on to consumers in the form of lower prices (which has an indirect effect of increasing real wages).[2] In support of this, a study by Kwon et al. finds that the profit rates of the top 1 percent of corporations for multiple sectors have remained about the same while concentration (share of receipts for the top 1 percent) has risen since the 1960s, meaning firms are passing on productivity gains to workers and consumers rather than keeping them.[3] (See figure 1 and figure 2.)

Figure 1: Top 1 percent corporations’ assets, receipts, and net income[4]

Figure 2: Profitability of the top 1 percent of corporations by assets[5]

As such, rather than focusing principally on the purported downsides of firm size, policymakers should not discount the benefits to the economy from firms that can gain efficiencies from the scale. This means policymakers need to reject neo-Brandeisian ideology and instead empirically examine the impact of rising concentration in each industry. Moreover, they need to revise the 2023 Merger Guidelines to encourage more mergers, especially those that result in minimal increases in concentration but generate significant productivity gains. This would ensure that larger, highly productive firms can continue to operate in the market, benefiting consumers, workers, and the economy alike.

This report 1) rebuts the neo-Brandeisian claims that concentration invariably negatively affects productivity and wages, 2) shows that concentration and productivity can have a positive relationship, and 3) shows that concentration and wages can have a positive relationship. Policymakers should:

▪ Modify the merger guidelines so that mergers are not presumed illegal based on market shares.

▪ Modify the guidelines so that regulators continue to give more consideration to efficiency defenses.

▪ Expand the type of efficiency defenses a firm can use to justify a merger under the consumer welfare model to include those under the general welfare model.

Rebutting The Argument That Concentration Hurts Productivity and Wages

In recent years, anticorporate advocates and policymakers have exaggerated a slight increase in corporate concentration and its impact on the economy as an excuse to break up large companies. In a recent report by the House Committee on Small Businesses, the authors argued that concentration has increased for 75 percent of U.S. industries, leading to market power for large incumbent firms.[6] As a result, they advocate for stronger antitrust regulations that would level the playing field for small businesses.[7] Similarly, in 2021, the White House’s Council of Economic Advisors wrote that “there is evidence that in the United States, markets have become more concentrated and perhaps less competitive across a wide array of industries.”[8] As a result, they claim this rise in concentration has hurt labor markets, consumers, and other businesses. Similarly, the Economic Innovation Group has also recently published a report claiming that concentration has increased and resulted in fewer small businesses entering the market.[9] Although less biased, other academic studies have also concluded that concentration has increased significantly. For example, a Federal Reserve study claims that the U.S. economy has become more than 50 percent more concentrated than it was in 2005.[10]

The market share of the four largest firms in a given industry rose only 1 percentage point, from 34.3 percent to 35.3 percent, from 2002 to 2017.

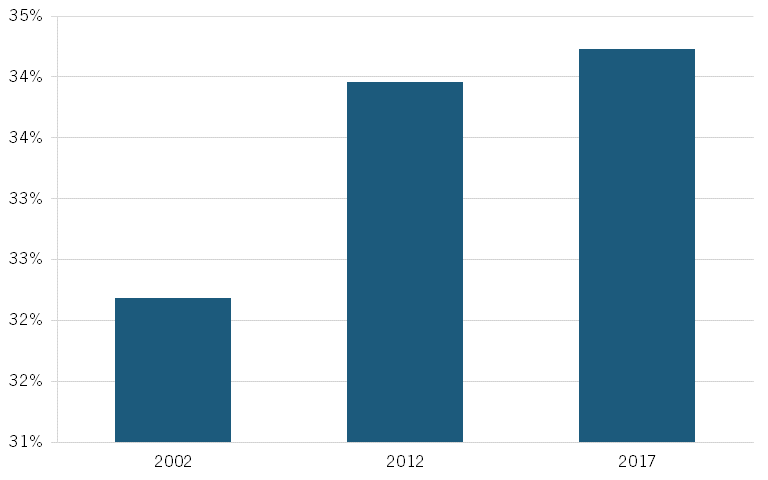

However, on closer examination, concentration has only risen slightly, and has actually decreased in the most concentrated industries. Using the most recent Census data on concentration, productivity, and compensation at the six-digit level of the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS), an Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) report concludes that the average C4 ratio, or the market share of the four largest firms in a given industry, rose only 1 percentage point, from 34.3 percent to 35.3 percent, from 2002 to 2017.[11] Further corroborating this, a simple average of the C4 ratios for 755 industries yields similar results: an increase of about 1.8 percent from 2002 to 2012 and 0.2 percent from 2012 to 2017.[12] (See figure 3.) Meanwhile, the ITIF study finds that the C8 ratio was even lower, rising from 44.1 to 44.7 percent in the same period.[13] But more importantly, it finds that the most concentrated industries in 2002 became less concentrated by 2017.[14] An analysis of 755 six-digit NAICS industries also gives similar results: the correlation between the change in the C4 ratio from 2002 to 2017 and the C4 ratio in 2017 was -0.28.[15] In other words, rising concentration (or less competition) cannot be attributed as the primary cause—and possibly is not a cause at all—of a series of economic ills, despite proponents’ claims.

Figure 3: Average C4 ratio for all available industries[16]

Indeed, further corroborating these findings, a study by Rossi-Hansbert et al. finds that rising national concentration does not always result in less competition because top firms contribute to rising national concentration and also to declining local concentration, a better measure of market power and competition.[17] More importantly, a study by Kwon et al. examining changes in concentration for the last century finds that steady increases in national concentration are a natural feature of the economy and a signal of industry growth.[18]

The reality is that, for the most part, economists are still trying to explain the productivity slowdown, which opens up a window for neo-Brandeisians to blame it on their bogeyman: big business.

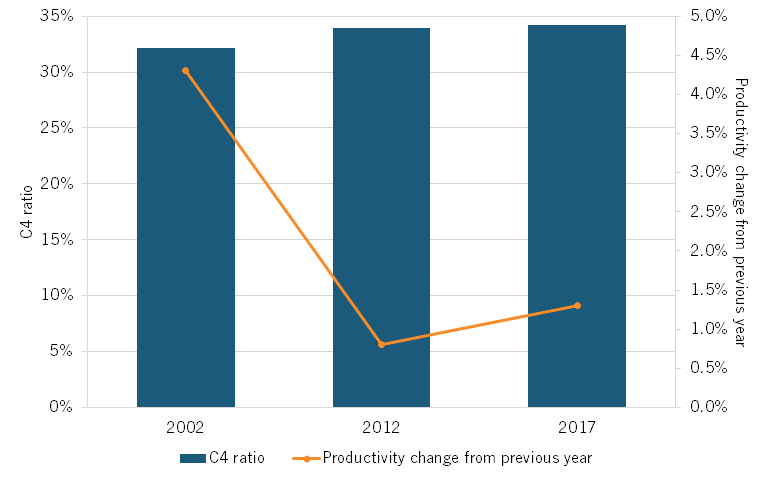

Yet, despite what evidence suggests about changes in concentration and the potential benefits, anticorporate activists continue to assert that concentration is the central problem facing the American economy. One of their claims is that rising concentration is leading to lower productivity growth rates, partly because rising concentration has coincidentally occurred alongside declining productivity growth. (See figure 4.) For example, a recent study by the House Committee on Small Business implies that rising concentration is hurting productivity growth, as it asserts that rising concentration has led to fewer start-ups, which neo-Brandeisians claim are better at allocating resources more efficiently.[19] The White House also made similar claims when it stated that “large businesses make it harder for Americans with good ideas to break into markets,” resulting in less competition and slow productivity growth.[20] Moreover, an EIG report develops a theoretical model linking rising concentration to low productivity growth.[21] However, the evidence that these reports base their claims on about the relationship between concentration and productivity growth is often flawed. For instance, part of the EIG report’s conclusion is based on the rise in concentration coinciding with productivity, but in no way does that show causality.[22]

Figure 4: C4 ratio and change in productivity from previous year[23]

Indeed, economists have attributed low productivity growth to a range of factors, but few have concluded that rising concentration is the primary and direct cause of low productivity growth. The reality is that, for the most part, economists are still trying to explain the productivity slowdown, which opens up a window for neo-Brandeisians to blame it on their bogeyman: big business. For example, a study by the San Francisco Fed concludes that “the relationship between concentration, competition, and productivity growth is subtle: rising concentration does not necessarily imply declining competition, and more competition does not necessarily stimulate growth.”[24] And what good evidence there is does not support the claim that concentration is causing low productivity growth: an Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) study shows that every OECD nation has seen productivity decline even though their changes in concentration levels differ.[25]

To further bolster their anticorporate campaign, neo-Brandeisians also allege that rising concentration is associated with, and the likely cause of, stagnating wages. In a 2018 article, the now-FTC Chair Lina Khan claimed that “the decline in competition is so consistent across markets that excessive concentration and undue market power now look to be not an isolated issue … this is troubling because monopolies and oligopolies … depress wages and salaries.”[26] Indeed, more recently, Chair Khan remarked in a White House Roundtable in 2022 that mergers can worsen labor market concentration, further depressing wages.[27] Similarly, the progressive Economic Policy Institute (EPI) has argued that product market concentration may have reduced wages by about 0.08 percent annually from 1979 to 2015.[28] The EPI has also highlighted that product market concentration can also increase labor market concentration, which further hurts wages.[29]

However, studies show that these claims are, at best, questionable. Indeed, a study by Azar et al. finds that wages are not negatively associated with product market concentration.[30] Furthermore, studies also show that stagnating wages are due to factors other than labor market concentration. For instance, an ITIF case study on nurses’ wages finds that nurses’ preferences on job location rather than changes in labor market concentration are the cause for wage markdowns.[31] Moreover, the study also finds that labor market concentration has declined despite stagnating wages.[32] Further corroborating these findings, a Cato Institute study finds a series of flaws in studies that conclude that labor monopsony power is negatively affecting wages.[33] Finally, the Cato Institute also found that a study by Azar et al. concludes that moving from the 25th to 75th percentiles in labor market concentration could be associated with a 4 percent increase in wages.[34]

Concentration and Labor Productivity

Despite claims to the contrary, rising concentration has been linked to increased productivity. In a study using data from 1972 to 2012, Ganapati found that increases in industry concentration are positively correlated with productivity growth.[35] Specifically, he concluded that “a 10 percent increase in the market share of the largest four firms is linked to a 1.6 percent increase in labor productivity.”[36] Corroborating these findings, another paper examining manufacturing industries from 1982 to 2015 concludes that industries with large increases in concentration and industries that are already highly concentrated tend to have better productivity growth.[37] This positive association between concentration and productivity is partly because the firms investing more in both IT and other intangible assets that boost productivity are bound to gain market shares. Indeed, an OECD study examining data from 2002 to 2014 finds that a 10 percentage point increase in intangible assets in an industry is associated with a 1.5 to 2.2 percentage point higher concentration.[38] Meanwhile, a study by Bessen concludes that proprietary software is related to top firms’ higher efficiency and can explain the 3 to 5 percent rise in industrial concentration since 1980.[39]

The positive association between concentration and productivity is partly because the firms investing more in both IT and other intangible assets that boost productivity are bound to gain market shares.

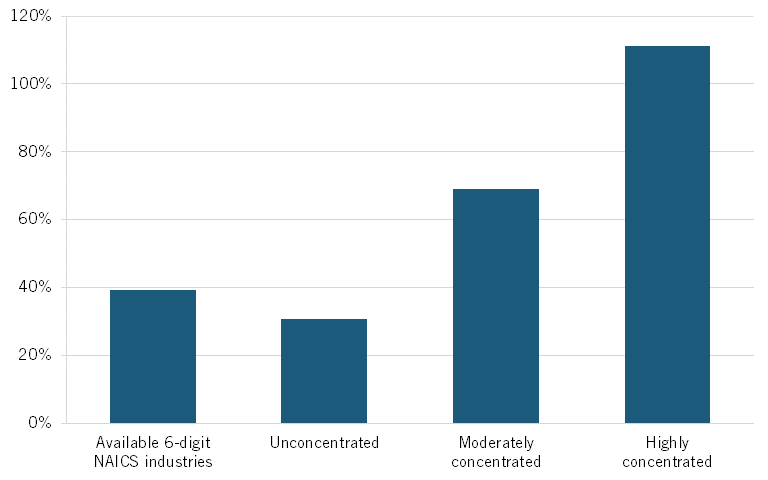

Indeed, ITIF examined 83 six-digit NAICS industries (with available concentration and productivity data) and similarly concluded that concentration can have a positive impact on productivity. In this analysis, industries with C4 ratios, or the market share of the four largest firms in an industry, above 80 percent are considered “highly concentrated,” industries with levels between 50 percent and 80 percent are considered “moderately concentrated,” and industries with levels below 50 percent are considered “unconcentrated.”

In 2017, the four industries that were highly concentrated experienced an average productivity growth of 111 percent from 2002 to 2017.[40] The 10 industries that were moderately concentrated had an average productivity growth of 68.9 percent and the remaining 69 industries that were unconcentrated had a growth of 30.8 percent.[41] This is compared with the average productivity growth of 39.3 percent for all 83 industries.[42] (See figure 5.) In other words, this shows that the more concentrated an industry is, the higher the average change in productivity, meaning that concentration can potentially be beneficial to the economy.

Figure 5: Average change in productivity index, 2002–2017, based on concentration levels in 2017[43]

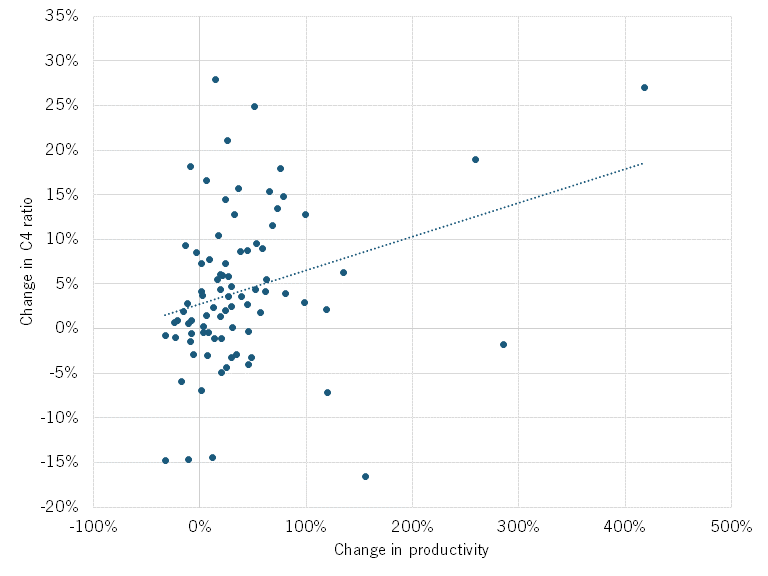

To better assess the relationship between concentration and productivity, this analysis also examines the relationship between changes in concentration and changes in productivity from 2002 to 2017. Figure 6 presents this relationship, with the y-axis showing the percentage point change in C4 ratio and the x-axis showing the percentage change in productivity from 2002 to 2017. As the trendline in the figure shows, the relationship between change in concentration and change in productivity is positive, with a correlation coefficient of 0.29.[44] Even when the three outlier industries (travel agencies, cable and other subscription programming, and video tape and disc rental) are removed, the relationship remains positive, with a correlation coefficient of 0.14.[45] In other words, industries that got more concentrated also got more productive in this period.

Figure 6: Change in C4 ratio and change in productivity, 2002–2017[46]

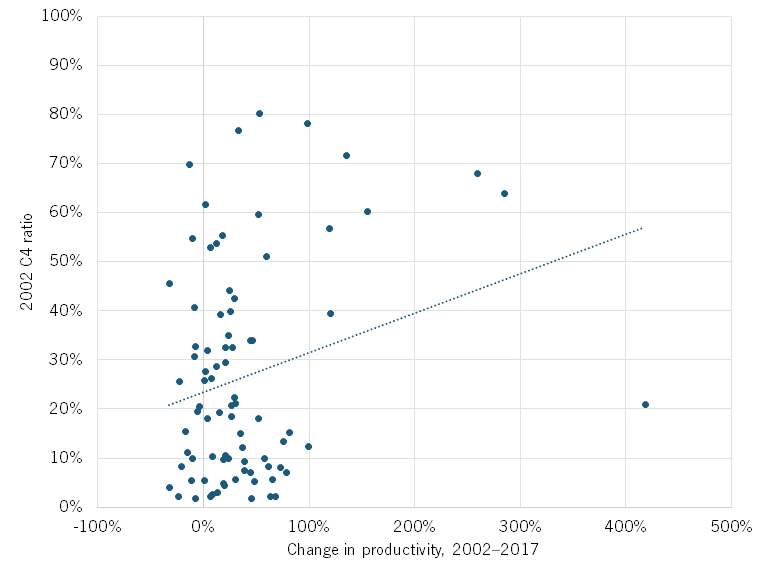

Another way to assess the relationship between concentration and productivity is to examine how productivity has changed for industries with varying levels of concentration. Figure 7 examines this relationship, with the y-axis presenting the 2002 C4 ratios and the x-axis presenting the change in productivity from 2002 to 2017. As the trendline in the figure shows, the relationship between industry concentration and changes in productivity is positive, with a correlation coefficient of 0.25.[47] In other words, the more concentrated an industry was in 2002, the higher productivity growth it experienced from 2002 to 2017. Again, when the three outlier industries (travel agencies, cable and other subscription programming, and video tape and disc rental) are removed, the relationship is still positive, with a correlation coefficient of 0.21.[48]

Figure 7: 2002 C4 ratio and change in productivity, 2002–2017[49]

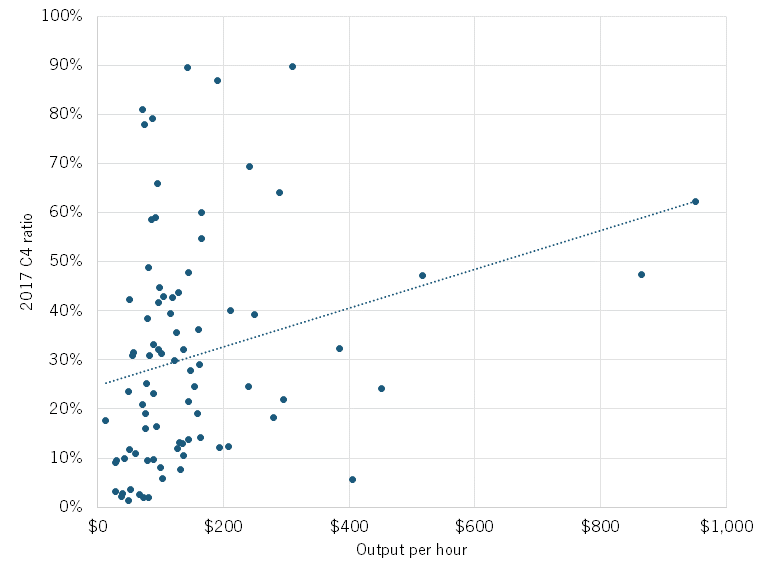

Finally, the analysis also examines whether more concentrated industries also tend to have higher productivity. Using Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) data on sectoral output and total labor hours, the sectoral output per hour worked was calculated for each industry to be used as a proxy for absolute labor productivity levels. Figure 8 shows this relationship, with the y-axis showing the 2017 C4 ratio and the x-axis showing the output per hour worked in 2017.[50] As the trendline shows, the relationship between industry concentration and output per hour worked is positive, with a correlation coefficient of 0.26.[51] Even when the three outlier industries (cable and other subscription programming, drugs and druggists sundries merchant wholesalers, and other gasoline stations) are removed, the relationship is still positive, with a coefficient of 0.20.[52] In other words, industries that are more concentrated also tend to have higher productivity.

Figure 8: C4 ratio and output per hour worked in 2017[53]

Numerous studies and data show that rising concentration is positively correlated with higher productivity and wages. It is very likely that this relationship follows an inverted U, as it has been shown to with innovation (highly concentrated and minimally concentrated industries innovate less while moderate concentration and market power boost innovation).[54] In sum, the economy can be better off with more firms with higher productivity.

Concentration and Labor Compensation

Notwithstanding claims that rising product market concentration leads to lower wage growth, the relationship between the two is not as clear-cut as anticorporate, anti-big business proponents make it seem. This is because large firms generally pay higher wages than do their smaller counterparts. Indeed, a World Bank study of more than 45,000 firms in more than 100 countries finds that larger firms generally pay wages that are twice as high as their small enterprises.[55] Furthermore, a study by Oi and Idson finds that firms with 500 or more employees pay wages that are 30 to 50 percent higher than firms with fewer than 25 employees.[56] A more recent ITIF analysis also finds that workers in firms with more than 500 employees earn about 38 percent more than those in firms with less than 100 employees.[57] At the state level, a study measuring the relationship between wages and firm size in Utah finds a positive relationship between wages and firm size.[58]

Studies have long attributed this wage premium to the higher productivity of larger firms. For instance, an article by Miller examining 450 industries finds that the four largest firms in an industry are about 37 percent more productive and offer 17 percent higher wages. Indeed, higher productivity is also why the World Bank study observes that larger firms tend to be more productive and offer higher wages.[59] Moreover, a recent study by Lallemand on the Belgian private sector finds that the size-wage premium is partly because of the “higher productivity and stability of the workforce in large firms.”[60] At the bottom, rising concentration may signal that firms are becoming more productive and growing larger in an industry, leading to higher wages for employees and, possibly, a growing economy.

Based on an analysis of 83 six-digit NAICS industries (with available data), the relationship between concentration and compensation, or wages, can be positive or negative.

Indeed, ITIF’s study of 83 six-digit NAICS industries (with available concentration and labor compensation data) similarly concludes that concentration has a positive impact on wages. Although hourly labor compensation is not an exact measure of wages for each industry, it is used as a proxy for wages because “wages and salaries” generally account for about 80 percent of compensation.[61] The categorization of C4 ratios as highly concentrated, moderately concentrated, and unconcentrated is the same as noted in the previous section. (Also, on average, large firms pay more in non-wage compensation than small firms do.[62])

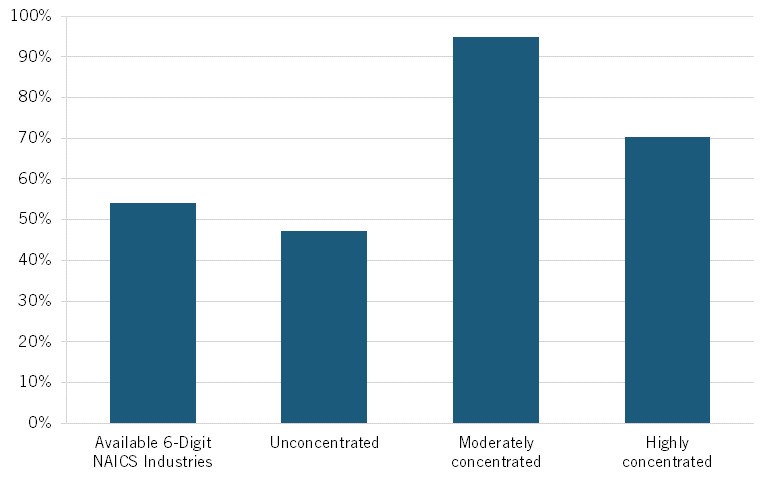

In 2017, the four highly concentrated industries experienced an average growth in hourly compensation of about 70 percent.[63] The 10 moderately concentrated industries saw an average growth in their hourly compensation of about 95 percent, and the remaining 69 unconcentrated industries only had a growth of about 47 percent.[64] This is compared with the average growth in hourly compensation of all industries of 54 percent.[65] (See figure 9.) Based on these findings, the relationship between concentration and compensation, or wages, can thus be positive or negative.

Figure 9: Average change in hourly compensation index, 2002–2017, based on concentration levels in 2017[66]

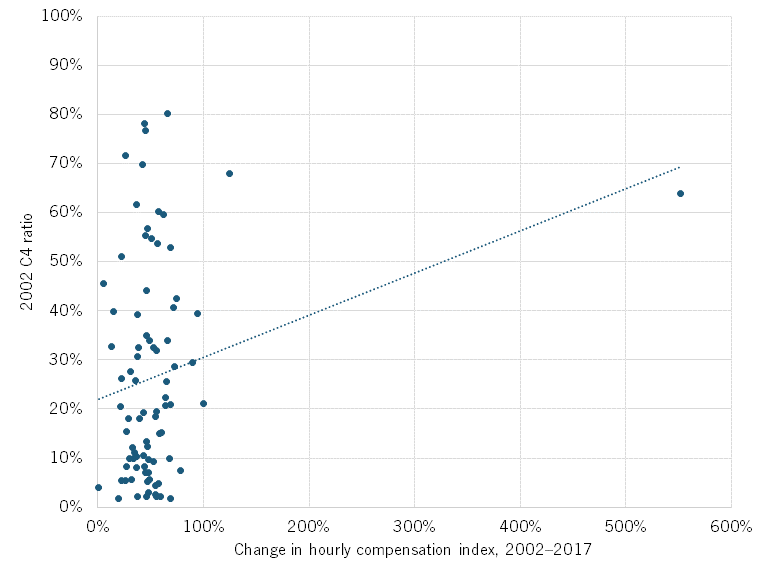

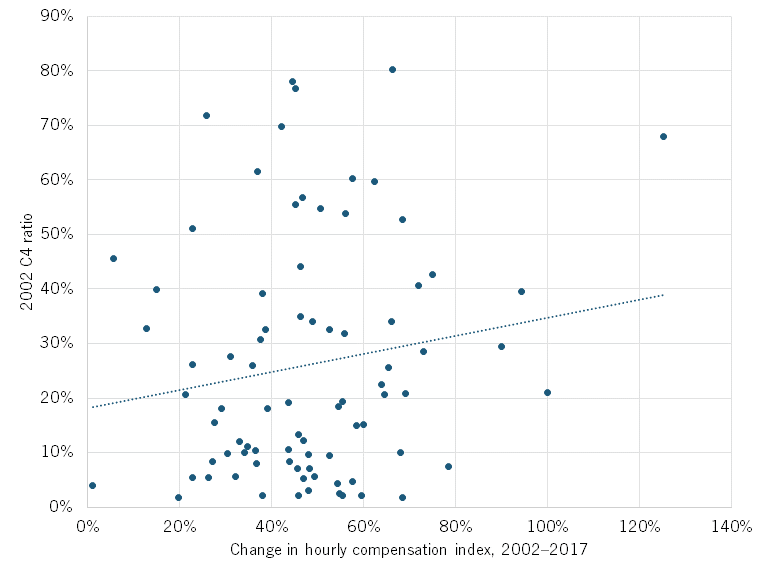

ITIF’s analysis also examines how concentration levels are related to changes in hourly compensation for the 83 industries with available data. In other words, do more concentrated industries tend to see more increases in their wages? Figure 10 presents this relationship, with the y-axis showing the 2002 concentration ratios for the four largest firms and the x-axis presenting the change in the hourly compensation index from 2002 to 2017.[67] As the trendline shows, the relationship between concentration and change in hourly compensation is positive, with a correlation coefficient of 0.23.[68] In other words, industries that were more concentrated in 2002 also saw a more significant change in their hourly compensation from 2002 to 2017.[69] Even when the outlier industry (cable and other subscription programming) is removed, the relationship still remains positive, with a coefficient of 0.16—albeit with some qualifications (see endnote).[70] (See figure 11.) As a result, concentration is positively correlated with stronger wage growth.

Figure 10: 2002 C4 ratio and change in hourly compensation index, 2002–2017 (with outlier)[71]

Figure 11: 2002 C4 ratio and change in hourly compensation index, 2002–2017 (no outlier)

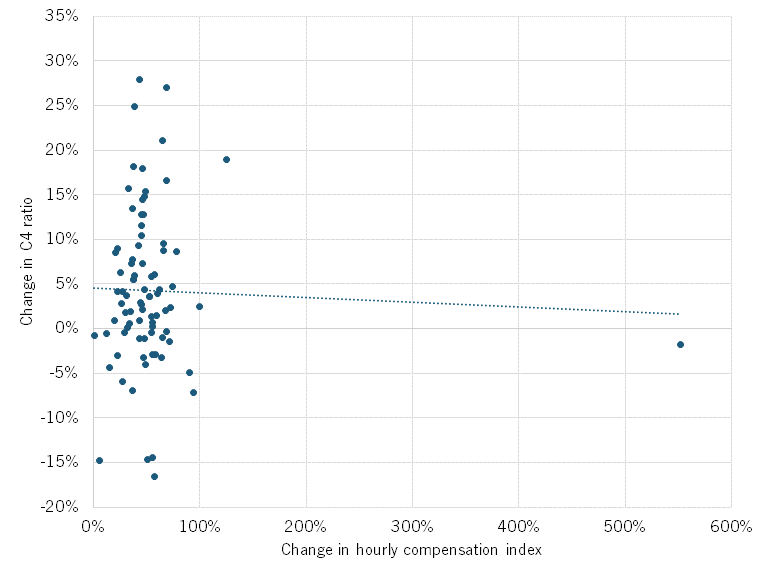

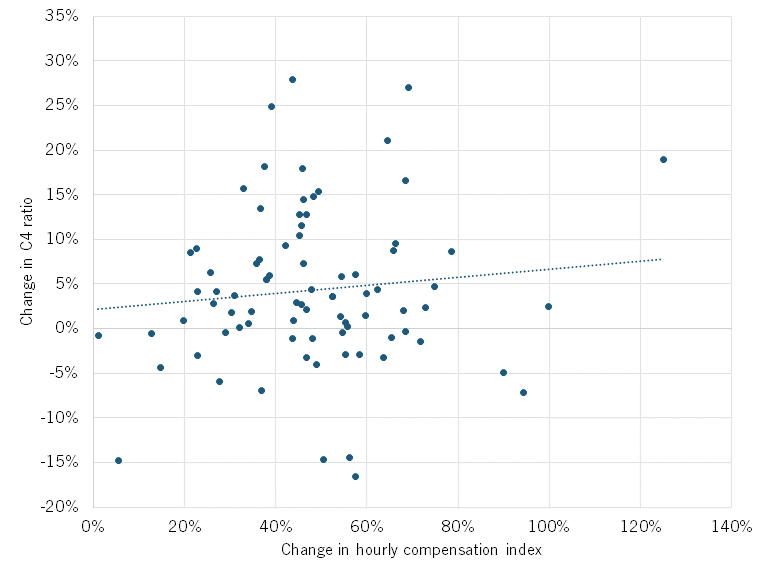

ITIF also looked at whether industries that became more concentrated also experienced more changes in their hourly compensation. Figure 12 presents this relationship, with the y-axis showing the change in C4 ratios from 2002 to 2017 and the x-axis showing the change in the hourly compensation index in the same period.[72] As the trendline in the figure shows, the relationship between the change in C4 ratios and the change in hourly labor compensation is slightly negative, with a correlation coefficient of -0.03.[73] However, this negative relationship is dependent on a single outlier industry: the cable and other subscription programming industry.[74] (See endnote for why this outlier industry’s numbers may be inaccurate and should be excluded from the analysis.[75]) When this outlier industry is removed, the relationship becomes positive, with a correlation coefficient of 0.11.[76] (See figure 13.) In other words, as an industry became more concentrated, generally its labor compensation also grew more, although the relationship was not strong.

Figure 12: Changes in C4 ratio and hourly compensation index, 2002–2017 (with outlier)[77]

Figure 13: Changes in C4 ratio and hourly compensation index, 2002–2017 (no outlier)

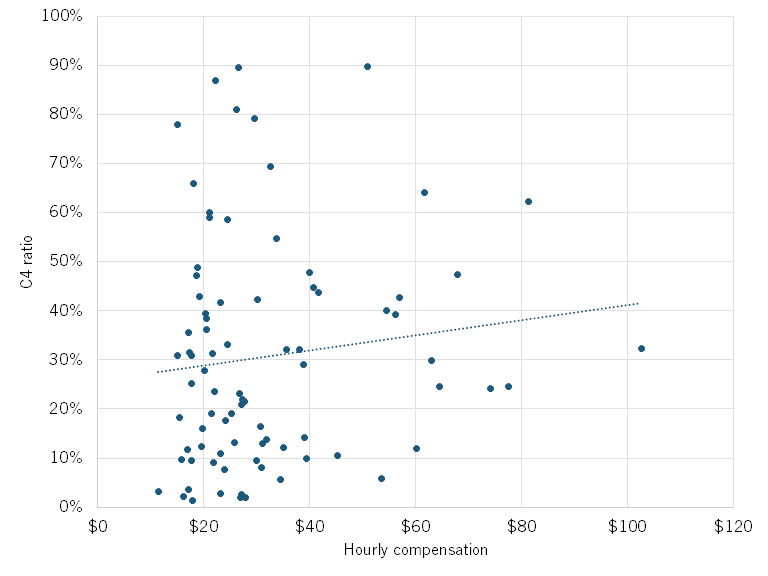

A third way to examine the relationship between concentration and compensation is to examine whether industries with higher concentration also have higher hourly labor compensation. Figure 14 presents this relationship, with the y-axis showing the 2017 C4 ratios and the x-axis showing the hourly labor compensation in 2017.[78] As the trendline shows, the relationship between concentration and labor compensation is positive, with a correlation coefficient of 0.12.[79] In other words, the more concentrated an industry is, the higher the hourly labor compensation it offers.

Figure 14: 2017 C4 ratios and hourly compensation[80]

In sum, the literature and data support the notion that concentration can potentially have a positive impact on labor compensation and its subcomponents, such as wages. As such, neo-Brandeisians and other anticorporate crusaders should not jump to the conclusion that rising concentration will automatically mean the economy is worse off and workers are harmed. If firms are becoming larger and paying higher wages because they are more productive, concentration will rise, but so will the number of people receiving higher wages. This can be beneficial to the economy.

Implications and Policy Recommendations

The policy implications are clear: Policymakers should reject the neo-Brandeisian antitrust program that demonizes bigger firms, as they usually benefit productivity and workers. This includes abandoning opposition to mergers.

Large firms have more resources to invest in intangible assets that boost their productivity. As a result of this higher productivity, corporate concentration will undoubtedly rise, but that does not automatically mean the economy is worse off. This higher productivity can increase output and lower prices, benefiting the economy. Moreover, this higher productivity will also benefit workers with higher wages. As such, in contrast to neo-Brandeisian claims that workers work for large companies because of monopsony power, a vast proportion of workers actually choose to work at these big companies because they are paid a higher wage. In other words, they are not forced to work for these companies; they want to because it is usually a ticket to the middle class. Thus, large firms boost the economy’s overall productivity while keeping the middle class healthy with opportunities for workers to achieve a higher wage. Given the benefits they provide, breaking up large companies would be both anticapitalist and antiworker.

However, rejecting neo-Brandeisian, anticorporate efforts to break up large firms is not enough. Policymakers need to take action to encourage firms to become larger so that they can boost both their own and the economy’s productivity. Indeed, one way increased concentration can be achieved is through mergers, which neo-Brandeisians and their allies often state is a central cause for increased concentration.[81]

First, policymakers should modify the merger guidelines so that mergers are not presumed illegal based on market shares. In the 2023 Merger Guidelines, the FTC and DOJ restored a structural approach to mergers when they declared that a merger is presumed illegal if its Herfindahl Hirschman index (HHI) is higher than 1,800 or the combined market share is greater than 30% and the delta HHI is over 100.[82] However, the issue with this approach is that it assumes the same level of HHI or that concentration has the same impact on all industries. But the reality is that high concentration may lead to scale economies and lower prices in one industry (e.g., aerospace) while having opposite effects for another. As such, instead of relying on structural presumptions, the guidelines should encourage regulators to examine the specific effects of increasing concentration from individual mergers. If a merger results in higher concentration but also higher wages, lower prices, increased output, or accelerated innovation, regulators should approve the merger. A policy like this would encourage firms to maximize their productivity gains from scale, thereby benefiting the economy.

Policymakers need to take action to encourage firms to become larger so that they can boost both their own and the economy’s productivity.

Second, policymakers should modify the guidelines so that regulators continue to give more consideration to efficiency defenses. In the 2023 Merger Guidelines, the agencies expressed skepticism that mergers can result in efficiencies and have now made it more challenging to assert pro-competitive effects as a justification for a merger.[83] The merger guidelines should return to the precedent set by previous guidelines wherein procompetitive effects and efficiency defenses are more readily credited and considered. This greater ability to defend their deals would encourage more firms to merge and allow the economy to benefit from productivity gains. Moreover, mergers that result in reduced jobs should be welcomed, not demonized, as this productivity enhancement is the key source of increases in living standards.

Lastly, policymakers should expand the types of efficiency defenses a firm can use to justify a merger under the consumer welfare model to include those under the general welfare model. Under the consumer welfare standard, firms have to show that the efficiency gains from a merger would be passed on to consumers. In other words, as Professor Hovenkamp has explained, “[A] ‘consumer welfare’ standard effectively requires a form of actual compensation … efficiency gains would satisfy the test if [the gains] were actually passed on to consumers, thus yielding prices that are no higher than they were prior to the merger.”[84] However, this approach is somewhat problematic because it does not seek to maximize efficiency in the economy, only the consumer surplus. Indeed, some mergers can result in higher productivity for the resulting firm post-merger that outweighs the price increases. For Hovenkamp, these deals would be approved under a general or total welfare standard: “[A] merger that produced $5 million in efficiency gains while raising aggregate prices by $4 million would be counted as efficient, assuming it did no other harm beyond raising prices.”[85]

The upshot is that firms with significant productivity potential from growth should be allowed to merge even if the merger would result in price increases, albeit with some limit, but to the benefit of the overall economy.

As such, adopting a general welfare standard would be another way for policymakers to modify the merger guidelines to accept and strongly consider efficiency defenses that may justify deals that result in minimal price increases but also significant productivity gains. However, policymakers could also set a threshold on the share of price increases that can occur post-merger for these efficiency defenses. This is because maximizing economic efficiency is important, but so is limiting the harm to consumers. The upshot is that firms with significant productivity potential from growth should be allowed to merge even if the merger would result in price increases, albeit with some limit, but to the benefit of the overall economy.

Conclusion

Despite claims by neo-Brandeisian and other anticorporate ideologues, increasing corporate concentration can boost productivity and wages. As we have seen, firms that have grown and acquired high levels of market shares tend to be more productive. Indeed, the rising concentration that results from these more productive firms gaining market shares is beneficial because it signals that an industry has higher-productivity firms producing more of its output. Moreover, as these firms become more productive and grow larger, they also tend to pay higher wages to their employees, reduce prices for consumers, and invest more in innovation.

Thus, policymakers should reject neo-Brandeisian efforts to break up large firms and instead encourage smaller firms that can benefit from productivity gains when they grow to become larger. The best way to encourage firms to maximize their productivity is to modify the 2023 Merger Guidelines to be more favorable to mergers, especially those that result in some minimal price increases but also significant productivity gains. Taking these actions would ensure that more firms become larger and more productive, thereby benefiting the overall economy.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Robert D. Atkinson and Joseph Coniglio for their guidance on this report. Any errors or omissions are the author’s responsibility alone.

About the Author

Trelysa Long is a policy analyst for antitrust policy with ITIF’s Schumpeter Project on Competition Policy. She was previously an economic policy intern with the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. She earned her bachelor’s degree in economics and political science from the University of California, Irvine.

About ITIF

The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) is an independent 501(c)(3) nonprofit, nonpartisan research and educational institute that has been recognized repeatedly as the world’s leading think tank for science and technology policy. Its mission is to formulate, evaluate, and promote policy solutions that accelerate innovation and boost productivity to spur growth, opportunity, and progress. For more information, visit itif.org/about.

Endnotes

[1]. Ufuk Akcigit et al., “Trends in U.S. Business Dynamism and the Innovation Landscape” (Economic Innovation Group, September 2023), https://eig.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Trends-in-U.S.-Business-Dynamism-and-the-Innovation-Landscape.pdf

[2]. Helena Vieira, “When productivity goes up, firms raise salaries,” London School of Economics, November 29, 2016, https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/businessreview/2016/11/29/when-productivity-goes-up-firms-raise-salaries/.

[3]. Spencer Kwon, Yueran Ma, and Kaspar Zimmerman, “100 Years of Rising Corporate Concentration” (Becker Friedman Institute for Economics working paper, February 13, 2023), https://bfi.uchicago.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/BFI_WP_2023-20.pdf.

[4]. Ibid.

[5]. Ibid.

[6]. Nydia Velazquez, “A Report on Competition in the Small Business Economy” (Washington DC: House Committee on Small Business, December 2023), https://democrats-smallbusiness.house.gov/uploadedfiles/sbc_report_on_competition_in_the_u.s._final.pdf.

[7]. Ibid.

[8]. Heather Boushey and Helen Knudsen, “The Importance of Competition for the American Economy,” The White House Council of Economic Advisors, July 9, 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/cea/written-materials/2021/07/09/the-importance-of-competition-for-the-american-economy/.

[9]. Akcigit et al., “Trends in U.S. Business Dynamism and the Innovation Landscape.”

[10]. Falk Brauning et al., “Cost-Price Relationships in a Concentrated Economy” (article in the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston 2022 Series on Curry Policy Perspectives, May 2022), https://www.bostonfed.org/publications/current-policy-perspectives/2022/cost-price-relationships-in-a-concentrated-economy.aspx.

[11]. Robert Atkinson and Filipe Lage De Sousa, “No, Monopoly Has Not Grown” (ITIF, June 2021), https://itif.org/publications/2021/06/07/no-monopoly-has-not-grown/.

[12]. U.S. Census Bureau, Economic Census 2002, 2012, and 2017 (concentration ratios of the 4, 8, 20, and 50 largest firms in 2002, 2012, and 2017), https://data.census.gov/all?q=Concentration+Ratio.

[13]. Atkinson and De Sousa, “No, Monopoly Has Not Grown.”

[14]. Ibid.

[15]. U.S. Census Bureau, Economic Census 2002, 2012, and 2017.

[16]. Ibid.

[17]. Esteban Rossi-Hansberg et al., “Diverging Trends in National and Local Concentration” (working paper in Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, February 2019, https://www.richmondfed.org/-/media/RichmondFedOrg/publications/research/working_papers/2018/pdf/wp18-15.pdf.

[18]. Spencer Kwon et al., “100 Years of Rising Corporate Concentration” (working paper from Becker Friedman Institute, February 2023), https://bfi.uchicago.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/BFI_WP_2023-20.pdf.

[19]. Velazquez, “A Report on Competition in the Small Business Economy.”

[20]. The White House, “Fact Sheet: Executive Order on Promoting Competition in the American Economy,” statements and releases, July 9, 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/07/09/fact-sheet-executive-order-on-promoting-competition-in-the-american-economy/.

[21]. Akcigit et al., “Trends in U.S. Business Dynamism and the Innovation Landscape.”

[22]. Ibid.

[23]. U.S. Census Bureau, Economic Census 2002, 2012, and 2017U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Labor Productivity and Cost Measures for Major sectors: nonfarm business, business, nonfinancial corporate, and manufacturing (labor productivity, costs, and hours measures), accessed March 25, 2024, https://www.bls.gov/productivity/tables/.

[24]. Peter Klenow et al., “Is Rising Concentration Hampering Productivity Growth?” (article by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, November 2019), https://www.frbsf.org/research-and-insights/publications/economic-letter/2019/11/is-rising-concentration-hampering-productivity-growth/#:~:text=The%20bottom%20line%20is%20that,does%20not%20necessarily%20stimulate%20growth.

[25]. Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development, The Future of Productivity (Paris: 2015), https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/economics/the-future-of-productivity_9789264248533-en.

[26]. Lina Khan, “The Ideological Roots of America’s Market Power Problem,” Yale Law Journal 127 (2018), https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3812&context=faculty_scholarship.

[27]. Lina Khan, “Remarks of Chair Lina M. Khan White House Roundtable on the State of Labor Market Competition in the U.S. Economy,” Federal Trade Commission, March 2022, https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/ftc_gov/pdf/Opening%20Remarks%20of%20Chair%20Lina%20M.%20Khan%20at%20WH%20Labor%20Roundtable.pdf.

[28]. Josh Bivens et al., “It’s not just monopoly and monopsony” (Economic Policy Institute, April 2018), https://files.epi.org/pdf/145564.pdf.

[29]. Ibid.

[30]. Jose Azar et al., “Concentration in U.S. labor Markets, Evidence from Online Vacancy Data” (NBER working paper, March 2018), https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w24395/w24395.pdf.

[31]. Julie Carlson, “Monopolies Are not Taking a Fifth of Your Wages” (ITIF, May 2022), https://itif.org/publications/2022/05/02/monopolies-are-not-taking-fifth-your-wages/.

[32]. Ibid.

[33]. Pedro Aldighieri et al., “Is There Monopsony Power in U.S. Labor Markets?” (CATO Institute, Summer 2022), https://www.cato.org/regulation/summer-2022/there-monopsony-power-us-labor-markets#a-review-of-the-evidence.

[34]. Ibid.

[35]. Sharat Ganapati, “Growing Oligopolies, Prices, Output, and Productivity” (paper by the Center for Economic Studies, November 2018), https://www2.census.gov/ces/wp/2018/CES-WP-18-48.pdf.

[36]. Ibid.

[37]. Sam Peltzman, “Productivity and Prices in Manufacturing During an Era of Rising Concentration” (paper from SSRN, May 2018), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3168877.

[38]. Matej Bajgar, Chiara Criscuolo, and Jonathan Timmis, “Supersize Me: Intangibles and Industry Concentration” (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, DSTI/CHE, September 13, 2019), https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/ce813aa5-en.pdf?expires=1715633814&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=A9C90FB64CECC85EA542982417345BEF.

[39]. James Sessen, “Information Technology and Industry Concentration,” Journal of Law and Economics 63, no. 531 (2020), https://scholarship.law.bu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1269&context=faculty_scholarship.

[40]. U.S. Census Bureau, Economic Census 2002, 2012, and 2017; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Labor Productivity and Cost Measures for Detailed Industries (labor productivity, costs, and hours measures, accessed March 1, 2024), https://www.bls.gov/productivity/tables/.

[41]. Ibid.

[42]. Ibid.

[43]. Ibid.

[44]. Ibid.

[45]. Ibid.

[46]. Ibid.

[47]. Ibid.

[48]. Ibid.

[49]. Ibid.

[50]. Ibid.

[51]. Ibid.

[52]. Ibid.

[53]. Ibid.

[54]. Philippe Aghion et al., Competition and Innovation: An Inverted-U Relationship, 120 Q. J. Econ. 701 (2005); Michael R. Peneder and Martin Woerter, Competition, R&D and Innovation: Testing the Inverted-U in a Simultaneous System, 24 J. of Evolutionary Econ. 653 (2014) (Switzerland); Michiyuki Yagi and Shunsuke Managi, Competition and Innovation: An inverted-U relationship using Japanese industry data, Discussion Papers 13062, Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI) (2013) (Japan); Michael Polder and Erik Veldhuizen, Innovation and Competition in the Netherlands: Testing the Inverted-U for Industries and Firms, 12 J. of Ind. Competition and Trade 67 (2012) (Netherlands); Chiara Peroni and Ivete Gomes Ferreira, Market competition and innovation in Luxembourg, 12 J. of Ind, Competition and Trade 93 (2012) (Luxembourg).

[55]. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherland et al., IFC Jobs Study (January 2013), https://www.handinhand.co.zw/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/IFC_JobStudyCondensedReport..pdf.

[56]. J. Adam Cobb, “Growing Apart: The Changing Firm-Size Wage Effect and Its Inequality Consequences” (paper from the University of Pennsylvania), https://faculty.wharton.upenn.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/fswe_orgsci-v3.3.pdf.

[57]. Robert Atkinson, “Reality Check: Facts About Big Versus Small Businesses” (ITIF, March 2021), https://itif.org/publications/2021/03/12/reality-check-facts-about-big-versus-small-businesses/.

[58]. Ari Fenn, “Firm Size and Wages” (paper by Utah Data Research Center, November 2023), https://udrc.ushe.edu/research/ra14/documents/firm_size_and_wages_november.pdf.

[59]. Judy Yang, “Large firms are more productive, offer higher wages, and more training (English),” The World Bank Group, January 2012, https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/651051467990379863/large-firms-are-more-productive-offer-higher-wages-and-more-training.

[60]. Robert Plasman and Francois Rycx, “Why do large firms pay higher wages? Evidence from matched worker-firm data,” International Journal of Manpower 26, no. 7/8 (2005), https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235316243_Why_do_Large_Firms_Pay_Higher_Wages_Evidence_from_Matched_Worker-Firm_Data.

[61]. Bureau of Economic Analysis, “Chapter 10: Compensation of Employees,” November 2019, https://www.bea.gov/system/files/2019-12/Chapter-10.pdf; U.S> Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Industry Productivity Measures: Concepts,” https://www.bls.gov/opub/hom/inp/concepts.htm.

[62]. Robert Atkinson and Michael Lind, Big is Beautiful: Debunking the Myth of Small Business (Massachusetts: MIT press, 2019).

[63]. U.S. Census Bureau, Economic Census 2002, 2012, and 2017; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Labor Productivity and Cost Measures for Detailed Industries.

[64]. Ibid.

[65]. Ibid.

[66]. Ibid.

[67]. Ibid.

[68]. Ibid.

[69]. Ibid.

[70]. The hourly compensation index for the cable and other subscription programming industry may be inaccurate. A change in absolute hourly labor compensation from 2002 to 2017 was positively correlated for 102 six-digit NAICS industries with a coefficient of 0.67. However, when the outlier industry is removed, the correlation is 0.86. This means that most industries have similar changes in the hourly compensation index and changes in absolute hourly compensation except for this outlier industry, signaling an error.; U.S. Census Bureau, Economic Census 2002, 2012, and 2017; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Labor Productivity and Cost Measures for Detailed Industries.

[71]. U.S. Census Bureau, Economic Census 2002, 2012, and 2017; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Labor Productivity and Cost Measures for Detailed Industries.

[72]. Ibid.

[73]. Ibid.

[74]. Ibid.

[75]. The hourly compensation index for the cable and other subscription programming industry may be inaccurate. A change in absolute hourly labor compensation from 2002 to 2017 was positively correlated for 102 six-digit NAICS industries with a coefficient of 0.67. However, when the outlier industry is removed, the correlation is 0.86. This means that most industries have similar change in hourly compensation index and change in absolute hourly compensation except for this outlier industry, signaling an error.

[76]. U.S. Census Bureau, Economic Census 2002, 2012, and 2017; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Labor Productivity and Cost Measures for Detailed Industries.

[77]. Ibid.

[78]. Ibid.

[79]. Ibid.

[80]. Ibid.

[81]. Michael Vita and F. David Osinski, “John Kwoka’s Mergers, Merger Control, and Remedies: A Critical Review,” Antitrust Law Journal 82, no. 361 (2018), https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/biographies/michael-g-vita/10_vita_osinski_alj_82-1_final_pdf.pdf.

[82]. Ted Bolema, “Decoding the 2023 FTC and DOJ Merger Guidelines: insights into Shifting Antitrust Enforcement,” Mercatus Center, February 15, 2024, https://www.mercatus.org/research/policy-briefs/decoding-2023-ftc-and-doj-merger-guidelines-insights-shifting-antitrust.

[83]. Ibid.

[84]. Herbert Hovenkamp, “Appraising Merger Efficiencies” (paper in University of Pennsylvania’s All Faculty Scholarship, 2017), https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2764&context=faculty_scholarship.

[85]. Ibid.

Editors’ Recommendations

June 7, 2021

No, Monopoly Has Not Grown

March 12, 2021