America Doesn’t Import Too Much From China; the Real Problem Is U.S. Exports Are Too Low

When looked at in isolation, the numbers are scary. America runs a goods and services trade deficit with China of more than $350 billion per year, and China holds over $800 billion in U.S. debt. Similarly large numbers have persisted for many years.

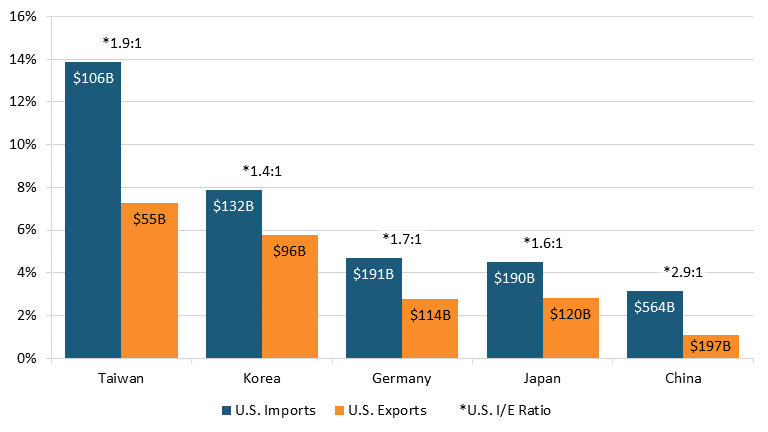

But when viewed from an Asian and global perspective, these imbalances are more predictable than shocking. America’s imports from China accounted for 3.1 percent of China’s GDP in 2022. (See figure 1.) In contrast, U.S. imports from Japan accounted for 4.5 percent of Japan’s GDP and 4.7 percent of Germany’s. For South Korea, it was 7.9 percent, while U.S. imports from Taiwan accounted for a whopping 13.9 percent of Taiwan’s GDP. America’s exports lag far behind its imports in all five nations, but the export shortage is especially wide with China. Similarly, as a share of their GDP, Japan, Taiwan and many other nations hold substantially more U.S. debt than China does. The main problem is the vast amount of U.S. debt in circulation.

Figure 1: U.S. imports and exports as a share of select trading partners’ GDP, 2022[1]

Adopting a cross-country perspective helps us see that while America’s dependence on imports from China grabs most of the headlines, the lack of U.S. exports to China and elsewhere is a bigger problem. Consider the data in figure 1, drawn from U.S. Census Bureau reports:

▪ The U.S. runs a large trade deficit with all five nations, but as a percent of GDP America’s imports from China and exports to China are less than with the other four.

▪ The ratio of U.S. imports from Japan to exports to Japan is 1.6 to 1, whereas with China it is 2.9 to 1. If America’s exports increased enough for it to have the same import/export ratio with China as it does with Japan, the U.S./China annual trade deficit would shrink by some $200 billion. The numbers for South Korea (1.4 to 1) are similar.

▪ The fact that the U.S. import to export ratio for Germany is around 1.7 to 1 suggests that the lack of U.S. exports is not just because of protectionism within Asia.

▪ The United States exports about one-fourth as much to Taiwan as it does to China. But the Chinese economy is more than 23 times the size of Taiwan’s. If U.S. exports to China were 23 times those to Taiwan, America would run a large trade surplus with China.

As the figure shows, when adjusted for GDP size, U.S. imports from China are significantly lower than those from the other four nations. Of course, U.S. exports to Japan, Korea, and Taiwan have a large defense component, which isn’t relevant to China. But this only reinforces the overall weakness of U.S. exports. It’s also true that many U.S. imports from China are made on behalf of American companies such as Apple, Dell, Walmart, Nike et al., whereas U.S. imports from Japan, Korea, and Germany are mostly from companies based in those nations—Toyota, Honda, Samsung, LG, Mercedes, Bosch, etc.

This difference in the nature of U.S. imports from China compared to those from Japan, Korea, and Germany is a complex and insufficiently discussed dynamic. Arguably, America’s imports from China are more benign than those from the other tigers as they often contribute directly to the success of U.S.-based firms. On the other hand, it means that some of America’s most important firms are even more dependent on China than the United States as a whole.

Moreover, if the goods that America imports from China could not be sourced from China, most of them would still have been made somewhere overseas, even the high-value ones. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, in 2022, America imported $634 billion worth of “Advanced Technology Products,” but only exported $391 billion, resulting in a deficit of $243 billion—an imbalance that has been rising over time.[2] Clearly, a core part of America’s trade deficit is that the United States lags in the competitive manufacturing of must-have, high-value goods.

Why Trade Deficits Matter

Export and import figures only tell part of the trade story. American firms such as Apple, Intel, Microsoft, Tesla, McDonalds, Marriott, Starbucks, Walmart, and many others do a great deal of business within China, which isn’t counted as U.S. exports. For example, Apple has China revenues of some $80 billion a year, about 20 percent of its total. According to The Economist, U.S., European, and Japanese firms did some $700 billion of business in China in 2021.[3] If half of this were from U.S. firms, the $350 billion would match the current trade deficit. Even if it is just a third, most of the deficit would be offset. But although America’s imports from China and the revenues of U.S. companies in China roughly balance out, trade deficits still matter. Consider these five reasons:

1. The success of U.S. multinationals in China is great for those companies and their shareholders, but, unlike export-driven manufacturing, it does relatively little in terms of creating jobs for U.S. workers.

2. The lack of domestic manufacturing in high-value areas raises important concerns regarding national and corporate resiliency and self-sufficiency, especially when these goods are sourced from China.

3. Manufacturing at scale is an important form of learning and a source of future innovation.

4. It’s generally much easier to move up the value chain from commodity manufacturing to advanced innovation than it is to move down the value chain from high-end services to competitive manufacturing.

5. U.S. trade deficits increase America’s indebtedness all around the world. The success of U.S. multinationals in China doesn’t significantly improve this situation.

Given all this, it seems safe to conclude that even though U.S. firms do a lot of business in China, it does not offset the downsides of today’s U.S./China trade deficit.

Debt Similarities

Similar alarms are sounded whenever China’s holdings of U.S. debt are viewed in isolation. China currently owns some $860 billion in U.S. government securities (which is down from previous highs of more than $1 trillion). Again, this seems like an enormous and dangerous number. But as with trade, it seems less so in context. China’s holdings are less than 3 percent of America’s total federal government debt of $32 trillion. Even compared to other nations, China’s U.S. holdings are not particularly large.

Foreign countries hold roughly 25 percent America’s federal government debt, or some $8 trillion. China holds about 10 percent of this total. However, Japan owns even more, and taken together, Europe holds more than Japan. Taiwan alone holds some $230 billion, despite having a GDP one-twentieth that of China.[4] America’s national debt is a serious problem and evidence of declining national governance and fiscal responsibility, but China is only a small part of the story. China’s large holdings are the predictable result of America’s massive debts, the essential international role of the dollar, and the large U.S./China trade deficit.

Managing Tiger Trade

Given the export-based strategies of all the Asian tigers, there have always been international trade tensions, especially during the 1980s between the United States and Japan. As they did with Japan, many pundits and policymakers now argue that China should reduce trade tensions by buying more American products. President Trump tried to bargain with President Xi toward this end. But as happened with Japan, no amount of American pressure and jawboning has led to a game-changing increase in exported high-value U.S. goods. America’s China export successes have been largely limited to agricultural products, timber, fossil fuels, and other commodities. Outside of military equipment, U.S. exports to Japan and Korea are similar in nature.

Unless and until American high-value exports become more competitive—which won’t happen quickly—there is only one proven way to address the trade deficit problem: requiring or incenting Asian companies to make more products in the United States. This was particularly important with cars. Once the major Japanese (as well as German and Korean) auto makers established large plants throughout the United States, trade tensions were substantially reduced. Efforts by Samsung and TSMC to make semiconductors in America could someday achieve similar results, but this is far from assured.

Unfortunately, Chinese investments in the United States are increasingly unwelcome (as they once were with Japan). While understandable, this could prove counterproductive. If America is to reduce tensions and increase mutual dependencies, then allowing, incenting, and/or requiring Chinese manufacturing in the United States—for batteries, solar panels, and electric vehicles, for example—is a strategy that could help. However, the political headwinds against such cooperation are currently very strong in both nations.

Sales, Not Decoupling

As we have previously written, China’s economy should be viewed primarily as a giant Asian tiger, not as a new form of state-sponsored capitalism.[5] This isn’t to dismiss China’s aggressive techno-economic practices, and the need for America to respond with much more effective and reciprocal policies that match China’s investments, subsidies, barriers, and other policies. It’s to remind western audiences that China has largely followed the same developmental playbook as the other major Asia economies, which also limited imports and subsidized exports, especially in their developing years. That Japan, Germany, and Korea all export many hi-tech products to China and have relatively balanced bilateral trade with China reinforces this view.

For many decades, the United States has run substantial trade deficits and suffered trade tensions with all its major Asian trading partners, as global manufacturing moved decisively to the Pacific region. China has followed this pattern but is different in three important ways: It is vastly larger than the other tigers in terms of both population and GDP; its competitive challenge to American industry is wider and deeper than the other tigers, and it is not a military or geopolitical ally. These important differences have led many in Washington to want to decouple from China by engaging in what is effectively a new cold war, featuring export bans, investment limits, sanctions, tariffs, and other forms of separation.

But broadly adopting such a confrontational strategy would be a fundamental mistake, as the Biden administration seems to have realized with its recent emphasis on de-risking, not decoupling. It’s important that U.S. firms succeed in China (albeit not in militarily sensitive areas). Not participating in the world’s largest market is a formula for competitive decline, and every dollar of U.S. sales reduces China’s global market influence. Unless the United States exports more to China, increases its sales within China, or encourages Chinese production within the United States, the only alternative to today’s bilateral trade deficit is to reduce Chinese imports. This is certain to increase tensions and reduce the prosperity of both nations. Unfortunately, this is the path that we are currently on.

Endnotes

[1]. Important export data from the U.S. Census Bureau, U.S. International Trade in Goods and Services (FT900), Part C: Seasonally Adjusted (by Geography), Exhibit 20. U.S. Trade in Goods and Services by Selected Countries and Areas, 2022 - BOP Basis, https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/Press-Release/current_press_release/index.html; GDP figures from The World Bank, DataBank, World Development Indicators, Gross domestic product 2022, https://databankfiles.worldbank.org/public/ddpext_download/GDP.pdf; Taiwan GDP from the International Monetary Fund via Statista, https://www.statista.com/statistics/727589/gross-domestic-product-gdp-in-taiwan/.

[2]. U.S. Census Bureau, “Trade in Goods with Advanced Technology Products,” accessed September 26, 2023, https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/balance/c0007.html.

[3]. The Economist, “Multinational firms are finding it hard to let go of China,” November 24, 2022, https://www.economist.com/business/2022/11/24/multinational-firms-are-finding-it-hard-to-let-go-of-china.

[4]. Statista, “Major foreign holders of United States treasury securities as of April 2023,” accessed September 26, 2023, https://www.statista.com/statistics/246420/major-foreign-holders-of-us-treasury-debt/.

[5]. David Moschella, “China Hasn’t Invented A New Type of Capitalism; It’s Following A Proven One” ITIF China’s Tech Challenge blog, April 24, 2023, https://itif.org/publications/2023/04/24/china-hasnt-invented-a-new-type-of-capitalism-its-following-a-proven-one/.