The Internet Didn’t Destroy Local Languages; It’s Helping Preserve Them

If you Google the question “Is the Internet killing local languages and cultures,” you will receive a lot of results that suggest the answer is yes. But if you look at them a bit more closely, you will see that the most dire warnings tend to be from 2010 to 2017. More recent results often take the opposite stance—that technology actually helps preserve local languages. It’s arguably one of the few areas where perceptions about the impact of the digital world have become more positive in recent years.

Advances in machine translation are clearly part of this shift in opinion. But there are also important economic, geopolitical, and cultural forces at work. Languages have always evolved as if in a marketplace. They compete against one another, with shifting winners and losers over time. Having a common cross-country language (Latin, French, English) is useful in that it can facilitate understanding and lower transaction costs, especially as the world becomes more globally integrated. But the roles of local and shared languages are always shifting, and right now they’re tilting back toward the local.

At an individual level, learning languages isn’t easy, so the learning process competes with other possible uses of our time. People often criticize Americans for only speaking English. But there’s no need to blame this on laziness or cultural arrogance. The main issue is that Americans have much less incentive to learn another tongue, as more than 1.4 billion people speak English all around the world. In contrast, if you are born in, for example, Denmark, then learning English opens up a great many career and personal possibilities, as opposed to limiting yourself to the market of 5.5 million people who speak Danish. While the global incentives to learn English are still very strong, they are less compelling than they were when American-led globalization was in its ascendancy.

Viewed more abstractly, the world’s 7,000 languages can be grouped into three main categories. The 300 most widely spoken ones are used by 90 percent of the world’s population. The remaining 10 percent speak some 6,700 languages, many having little or no written form at all.[1] Obviously, these are two very distinct “markets” that need to be assessed separately. A third group consists of the languages that dominate online. It’s estimated that just 20 languages account for some 95 percent of all Internet content, with nearly 60 percent of this content being in English.[2] Machine translation will be a decisive factor in determining how these three groups relate to one another going forward.

Peak English?

Even before deep learning, large language models, and inexpensive computer storage and processing power enabled major advances in machine translation, significant changes in language learning incentives were already underway. Consider the shifts that have taken place in recent years:

▪ The rise of China. The appeal of English was driven by America’s global leadership, the dominance of its tech firms, and the lasting influences of the former British Empire. China challenges all three factors. In addition to its economic and technological power, it is developing close bilateral relationships all around the world. In many countries, speaking Chinese is now often more valuable (because it is more scarce) than speaking English.

▪ A divided America. The flip side of the rise of China is the fact that America’s image around the world has been tarnished by wars, mass shootings, crime, drugs, political polarization, January 6, and more. Work and student visa restrictions have also lowered the value of speaking English for many individuals.

▪ Brexit. Over time, the United Kingdom’s departure from the European Union will tend to decrease the role of the English language within Europe. European citizens’ incentives to learn and use French and German will inevitably increase.

▪ “Splinternet.” Countries are increasingly asserting technological sovereignty within their borders in areas such as media ownership, permissible speech, and data usage, as well as in e-commerce, transportation services, payments, and other digital applications. This splintering of the Internet strongly favors the increased use of local languages.

▪ Cultural preservation. In every part of the world, there are renewed efforts to protect local languages, often with substantial national and citizen support.[3] For example, requiring at least some teaching and use of indigenous languages in K-12 schools is important for their long-term survival. Such initiatives will sometimes make learning English a third or fourth option.

All of the above have changed the global demand for languages, and explain why the dire warnings of an all-pervasive English Internet have receded. Taken together, the five dynamics above suggest that the world has probably passed its peak English period (at least for now). For the foreseeable future, English will continue to be the most common language for science, business, entertainment, and many other global activities. Nevertheless, country and regional languages are strengthening.

AI’s Impact

We can use the groupings of 20, 300, and 6,700 languages to better understand the likely economic and cultural impact of greatly improved machine translation. By looking at how AI changes both the competition between languages and incentives to learn one, we can see that the overall impact of technology on local language resiliency is most likely to be positive. AI will reduce—but far from eliminate—the economic value of speaking a common second language, and thus it will reduce—but far from eliminate—the incentive to learn one. Consider the patterns within each group today:

The Top Twenty

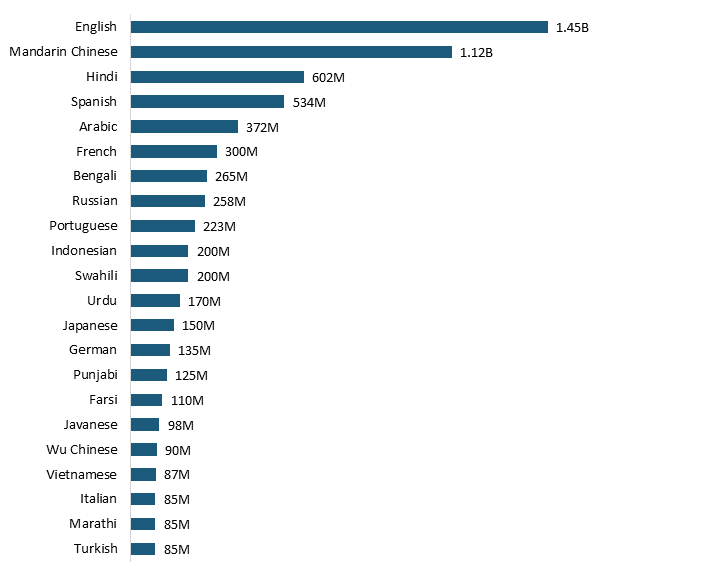

Google supports all of the world’s top 20 most widely spoken languages (figure 1), and firms such as Baidu have important Chinese translation capabilities, which will be essential in serving China both internally and internationally. The fact that six of these languages are widely used across India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh suggests significant machine-translation opportunities in the Indian subcontinent as well.

Figure 1: Top 20 most widely spoken languages by number of speakers, 2023[4]

While the quality of each translation pairing varies, it’s fair to say that useful and ever-improving capabilities will be available for pretty much all 20 of these languages. If so, it seems likely that users of web sites, other online content, devices such as Alexa, and even via mobile phone conversation in real time will increasingly be able to toggle between languages quite effectively. This will tend to reduce the online competition between languages because one won’t always have to choose one language over another. Similarly, from an individual perspective, the knowledge that one can reliably translate English language content into one’s native tongue could substantially reduce the incentive to become highly fluent in English.

To be clear, the incentives to learn English or another second language won’t go away. There are still many important career, cultural, and personal benefits to being bilingual or multilingual. But on the margin, the necessity of such efforts will likely be less than during the peak English years from 2005 to 2015, and this bodes well for the vitality of the top 20 languages.

The Core 300, or Is It 1,000?

As noted earlier, 300 languages are used by some 90 percent of the human population, so when thinking about the impact of technology on the world’s languages, this is obviously the most influential group. It’s also the hardest one to predict. Today, Google’s translation services support 133 languages. It seems logical that for those languages where quality translation services are available, the dynamics will be similar to those for the Top 20. On the margin, effective machine translation services will tend to strengthen the use of local languages and reduce the incentive or need to learn new ones.

But for those languages that do not have effective translation services, the logic would seem to run the other way. From a career, cultural, and personal perspective, important forms of content might not be available in one’s native tongue, and thus the incentive to learn English or another widely used language would rise. Once the need for a second language increases, competition with the local language intensifies, especially in business. Overall, it seems likely that availability and quality of translation for the 170 languages not yet supported will be a decisive factor going forward.

This is why the 1,000 Languages Initiative that Google announced in November 2022 could be so important.[5] While there are other important translation companies—Microsoft, Amazon, DeepL, Systran, Baidu, Youdao, and others—Google is still the market leader. If the company, or one of its rivals, can successfully get to anywhere near 1,000, the machine translation era will have fully arrived, along with all of the dynamics that come with it. As Google research scientist Yu Zhang and software engineer James Qin wrote in a recent blog post:

Last November, we announced the 1,000 Languages Initiative, an ambitious commitment to build a machine learning (ML) model that would support the world’s one thousand most-spoken languages, bringing greater inclusion to billions of people around the globe. However, some of these languages are spoken by fewer than twenty million people, so a core challenge is how to support languages for which there are relatively few speakers or limited available data. Today, we are excited to share more about the Universal Speech Model (USM), a critical first step towards supporting 1,000 languages. USM is a family of state-of-the-art speech models with 2B parameters trained on 12 million hours of speech and 28 billion sentences of text, spanning 300+ languages.[6]

We wish them luck.

Indigenous Preservation

For the 6,700 less-used languages, the dynamics are entirely different. Here, there is much less emphasis on the competition between languages. These languages will never be competitive in the sense of largely replacing much more widely used ones. Individual economic incentives are also much less of a factor, as the career benefits of learning rarely used languages are relatively low. What drives efforts in this area is cultural and familial demand—the sense that these languages are worth preserving regardless of their economic impact. It’s an entirely different mindset.

The main question is whether technology will help or hurt such efforts. As more and more communication takes place online, the lack of digital support for indigenous languages is a significant negative factor, especially for those languages with little to no written form at all. On the other hand, there are many examples of how technology is now helping preserve local languages, including:

▪ Local languages no longer have to stay local, as people can move around the world and still be closely connected to a particular language community.

▪ Apps, emojis, and dual-language stories are being used to better appeal to children who learn languages much more easily than adults.

▪ Technology can preserve the past, so that whatever language data is digitally captured—dictionaries, grammar, pronunciations, scripts, stories—is never lost.

▪ Machine learning can leverage whatever data is available to see language patterns that humans either can’t or don’t have time or energy for. AI is even being used to better understand “dead languages,” such as ancient Greek.[7]

But in the end, the preservation of rarely used languages is a primarily matter of will at an individual, local community, and increasingly at a regional and national level. While some indigenous languages will continue to disappear, given the many organizations now focused on preserving them, there is reason for optimism. In this sense, the indigenous language situation closely resembles efforts to protect and revitalize endangered species, which presents a similarly mixed picture of some surviving and others not.

A Boon for Translators

One of the worst language predictions has been that machine translation services will increasingly eliminate the need for human translators. This is clearly not the case. Regardless of language, for documents that need a high-quality translation—laws, government, business, creative expressions, and more—human review and editing is typically required. Even moderately sensitive content often requires at least some level of human oversight to avoid embarrassing errors. Most importantly, the use of AI to produce the first translation draft can make skilled and scarce human translators vastly more productive. AI greatly lowers the overall cost of translation, and when costs go way down, volumes go way up, with just about everyone benefiting.

About This Series

ITIF’s “Defending Digital” series examines popular criticisms, complaints, and policy indictments against the tech industry to assess their validity, correct factual errors, and debunk outright myths. Our goal in this series is not to defend tech reflexively or categorically, but to scrutinize widely echoed claims that are driving the most consequential debates in tech policy. Before enacting new laws and regulations, it’s important to ask: Do these claims hold water?

About the Author

David Moschella is a non-resident senior fellow at ITIF. Previously, he was head of research at the Leading Edge Forum, where he explored the global impact of digital technologies, with a particular focus on disruptive business models, industry restructuring and machine intelligence. Before that, David was the worldwide research director for IDC, the largest market analysis firm in the information technology industry. His books include Seeing Digital—A Visual Guide to the Industries, Organizations, and Careers of the 2020s (DXC, 2018), Customer-Driven IT (Harvard Business School Press, 2003), and Waves of Power (Amacom, 1997).

About ITIF

The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) is an independent, nonprofit, nonpartisan research and educational institute focusing on the intersection of technological innovation and public policy. Recognized by its peers in the think tank community as the global center of excellence for science and technology policy, ITIF’s mission is to formulate and promote policy solutions that accelerate innovation and boost productivity to spur growth, opportunity, and progress. For more information, visit us at www.itif.org.

Endnotes

[1]. The Rosetta Project, “About the 300 Languages Project,” webpage accessed July 27, 2023, https://rosettaproject.org/projects/300-languages/about/.

[2]. Statista, “Languages most frequently used for web content as of January 2023, by share of websites,” accessed July 27, 2023, https://www.statista.com/statistics/262946/most-common-languages-on-the-internet/.

[3]. See, for example, the Endangered Languages Project, https://www.endangeredlanguages.com/.

[4]. Federico Blank, “Most Spoken Languages in the World in 2023,” blog post, Lingua Language Center, Broward College, April 23, 2023, https://lingua.edu/the-most-spoken-languages-in-the-world/.

[5]. Jeff Dean, “3 ways AI is scaling helpful technologies worldwide,” Google blog post in The Keyword, November 2, 2022, https://blog.google/technology/ai/ways-ai-is-scaling-helpful/.

[6]. Yu Zhang and James Qin, “Universal Speech Model (USM): State-of-the-art speech AI for 100+ languages,” Google blog post in Research, March 6, 2023, hhttps://ai.googleblog.com/2023/03/universal-speech-model-usm-state-of-art.html.

[7]. Jane Recker, “A New A.I. Can Help Historians Decipher Damaged Ancient Greek Texts,” Smithsonian Magazine, March 16, 2022, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/a-new-ai-can-help-historians-decipher-damaged-ancient-greek-texts-180979736/.