Export Controls Shrink the Global Markets U.S. Semiconductors Need to Survive

If the United States is to win the techno-economic battle instigated by China, then trade policy must prioritize global market access for advanced industries with high fixed costs, like aerospace, software, biopharmaceuticals, and especially semiconductors. Yet, the current export controls on chips and semiconductor equipment reduce the available market size for U.S. firms, potentially hurting America’s mid- to long-term competitive advantage.

Semiconductors, like virtually all advanced-technology industries, are characterized by high fixed costs compared to marginal costs. That means they must incur very high upfront costs before they can even produce the first chip for sale. As such, the average cost of a chip usually significantly exceeds its marginal cost. Economists describe such industries as experiencing increasing returns to scale, meaning that each additional unit sold yields a higher rate of profit because costs decline. McKinsey estimates that:

Designing a 5 nm [nanometer] chip costs about $540 million for everything from validation to IP qualification. That is well above the $175 million required to design a 10 nm chip.... We expect that R&D costs will continue to escalate, especially for leading-edge products.

That does not include construction costs. Fabrication module construction costs for a 5 nm chip facility are estimated to be $5.4 billion, compared to $1.7 billion for a 10 nm chip fab. Since all these costs must be incurred before a single chip is sold, companies often must sell millions of chips before they can even break even. And importantly, each additional chip costs less to make than the one before it (in terms of total costs, fixed plus marginal) and the company’s profit per chip sold also increases, enabling the company to boost research and development (R&D).

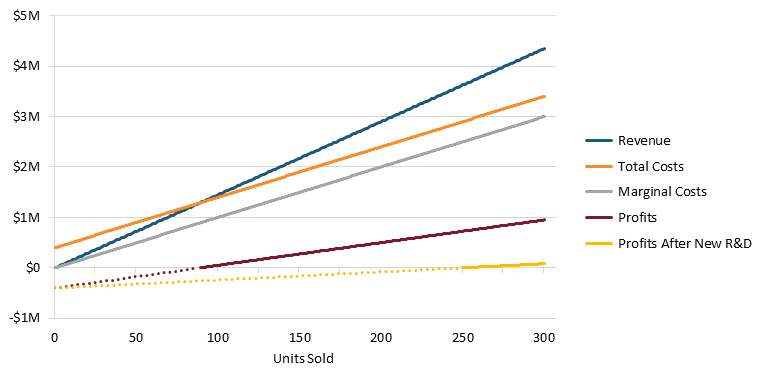

Figure 1 illustrates the cost structure of a hypothetical firm for which fixed costs are 40 times marginal costs—$400,000 and $10,000, respectively. In other words, the company must spend $400,000 on R&D, design, machinery, and other fixed costs before it can produce its first unit. It then costs $10,000 to make each unit in terms of energy, materials and labor, and the company can sell them for $14,450 per unit. Because of its high fixed costs, the company loses money until it sells at least 88 units. At that point, it makes an increasing profit on each additional unit sold. For these industries, scale is everything. Imagine if, because of export controls, the size of the market is limited to 75 units. In this case, the company would suffer a loss of $62,500. But if there are no export controls, then the company could earn a profit of $50,000 after selling 100 units. Meanwhile, whereas the total cost for producing the 75th chip would be $15,333, the total cost for producing the 100th chip would drop to $14,000. Now imagine the company needs to invest 20 percent of its revenues in new R&D to remain competitive. That moves the goalpost; it would require selling more than 250 units to become profitable.

Figure 1: Hypothetical firm with fixed costs 40 times greater than marginal costs

This is why scale is so critical for semiconductors, and why if America wants to regain its semiconductor lead—which the CHIPS Act will help accomplish—the federal government must do all it can to maximize the available market. Doing so will allow U.S. firms to sell products at more competitive prices and maximize R&D investments to stay competitive in future product cycles. Given that U.S. and allied semiconductor firms are in increasingly stiff competition with China, a critical factor for success is which country captures more marginal new sales.

If U.S. export policy limits sales to China, then U.S. costs won’t fall as much as they would otherwise, which will make their products less competitive. American companies will be less profitable, so they will have less to invest in critically needed R&D. In contrast, export controls will enable China to gain scale, allowing it to sell its chips for lower prices and achieve higher profits (or lower levels of government-subsidized losses) to invest in next-generation semiconductors.

Global market access is existential for industries with high fixed costs. Otherwise, costs won’t fall, R&D won’t increase, and competitors will gain structural advantages that ultimately can lead to the demise of advanced U.S. firms and industries with high fixed costs. It’s time for U.S. trade and national security policy to recognize this more nuanced and sophisticated reality.

Editors’ Recommendations

Related

November 10, 2025

Decoupling Risks: How Semiconductor Export Controls Could Harm US Chipmakers and Innovation

December 19, 2025