NFTs: US Policies and Priorities in 2023

Non-fungible tokens, or NFTs, offer unique policy challenges. While the United States has taken some important steps to address the potential risks and benefits of the technology, there is more policymakers can do to protect consumers while encouraging innovation.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Key Takeaways

Contents

Executive Order on Digital Assets 13

Pass Legislation Clarifying Regulatory Responsibilities 17

Strengthen Enforcement Capabilities 18

Create an Online Hub for Digital Asset Policies 18

Appendix: Example NFT Metadata for BAYC #599. 19

Introduction

Non-fungible tokens, or NFTs, are an increasingly popular technology that acts as a digital certificate of ownership. Initially used for digital collectibles, including digital art and virtual pets, they have become more mainstream in the past couple years, in part due to widespread speculation in the market driven by volatile prices and significant earnings by early adopters. As the technology has matured, different sectors have experimented with new use cases for it, including in gaming, entertainment, and fashion, and the technology is poised to be a key component of the metaverse—a shared, immersive virtual space where people can interact online.

NFTs raise many different policy issues, including those related to financial regulation, intellectual property (IP) rights, consumer protection, energy consumption, privacy, and content moderation. While policymakers in the United States have struggled to keep pace with the rapid evolution of the technology, they have already taken many steps to address some of these issues. But there is more they can do, including passing legislation to clarify regulatory responsibilities, strengthening enforcement capabilities across federal agencies, simplifying tax compliance, and creating an online hub for policies about NFTs and other digital assets.

Overview of the Technology

Blockchains are digital ledgers that record information that is distributed among a network of computers. Blockchains consist of a series of digital “blocks” that are securely linked together using cryptography. These blocks record information such as financial transactions, agreements between parties, and ownership records. Each computer in the network, referred to as a node, can store a copy of the blockchain. The nodes form a distributed peer-to-peer network, where updates are shared and synchronized between all nodes.[1]

Whereas in the past users needed a trusted intermediary, such as a bank or government agency, to ensure the integrity of these types of records, blockchains eliminate the need for a centralized authority. Instead, blockchains maintain agreement between all participants using a “consensus protocol”—a set of rules that allow nodes to determine when to add new information to the blockchain. Consensus protocols are designed to make the blockchain resistant to tampering.

The first and most well-known blockchain is Bitcoin. Created in 2009, Bitcoin uses a “proof of work” consensus protocol that requires nodes in the network to compete to solve complex cryptographic puzzles before a new block can be added. These nodes are called “miners” and they receive a reward for being the first to complete a puzzle. Other blockchains use alternative consensus methods, which reduce the computer power, and thus energy, needed to operate the network.

One popular use of blockchain is for cryptocurrencies. A cryptocurrency is a digital currency that uses cryptography to record and secure transactions. For example, bitcoin is a cryptocurrency that uses the Bitcoin blockchain. (Bitcoin with a capital “B” refers to the protocol, while bitcoin will a lowercase “b” refers to the cryptocurrency.) Other popular cryptocurrencies include ether, which runs on the Ethereum blockchain; XRP, which runs on the XRP ledger; and BNB (Binance Coin), which runs on the BNB Chain. There are also popular stablecoins, such as Tether and USD Coin, which are cryptocurrencies pegged to the U.S. dollar. Cryptocurrencies, like fiat currencies, are fungible, meaning one unit of the currency is interchangeable for another one.

NFTs are another popular use of blockchain technology. They can be thought of as digital certificates of ownership. In fact, the original technical specification for NFTs referred to them as “deeds.”[2] NFTs have interesting properties. First, NFTs (as the name implies) are non-fungible, meaning they are not interchangeable. Unlike coins in cryptocurrencies, NFTs are unique and one NFT is not a perfect substitute for another. Second, NFTs (again, as the name implies) make use of asset tokenization, a process that involves creating a digital token to represent a tradeable digital or physical asset. Tokens can represent almost any digital asset, such as digital art and domain names, or physical assets, such as real estate or vehicles. Third, NFTs are programmable, and include code stored on the blockchain. This code is called a “smart contract.”

A smart contract is code stored on the blockchain that runs automatically when certain conditions are met. Developers can customize this code, allowing for many different uses. However, once written to the blockchain, the code is immutable (i.e., it cannot be changed). As with anything on the blockchain, the code is public, so anyone can inspect it. The benefit of smart contracts is they execute automatically, so contracting parties do not need to involve a third party or spend time manually completing transactions. As discussed later, smart contracts are a key feature of NFTs that enable many interesting applications.

NFTs are created through a process called “minting.” When an NFT is minted, metadata about the token is added to the blockchain (see the appendix for sample metadata). The metadata includes information such as a name, description, and other details about the NFT. It also contains technical details, such as a token ID, a token standard, a creation date, and an address on the blockchain for the smart contract. All this information is publicly available on the blockchain, allowing buyers and sellers to track and trace ownership of NFTs to help verify their authenticity.

Digital assets, such as images or videos, are not typically stored on the blockchain itself. Instead, the NFT’s metadata includes a URL to the digital file. This link needs to be stable and persistent, since it cannot change. Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP), the protocol used widely for websites, is not ideal for this purpose, as someone could change the file on a server or redirect a domain name to a different IP address. In other words, whoever controls the link controls the content. Many NFTs instead use InterPlanetary File System (IPFS), a peer-to-peer file sharing protocol that uses content-addressed storage, which means users can store and retrieve files based on a hash, or a fingerprint, of the content. This method ensures that URLs for off-chain content are permanent and preserves the integrity of the data.[3]

Users buy and sell NFTs through private sales, auction houses (e.g., Sotheby’s or Christie’s), and online marketplaces. Popular online marketplaces include OpenSea, Rarible, Binance, Nifty Gateway, and SuperRare. Users purchase NFTs on these marketplaces using fiat currency or cryptocurrency. Once a user purchases an NFT, it is either held by a third party (e.g., the online marketplace) or a user’s cryptocurrency wallet.

There are two primary technical standards for creating NFTs. The first, ERC-721, was originally created by the Canadian company Dapper Labs in 2017.[4] The company used the standard to develop its popular CryptoKitties game wherein users can buy, breed, and trade virtual cats (a.k.a. “furrever friends”) with different features.[5] Developers then created a second NFT standard, ERC-1155, to make it possibly for buyers and sellers to bundle multiple tokens into a single transaction. Since blockchain transactions incur fees, allowing batch transactions can save significantly on transaction costs.[6]

Emerging Use Cases

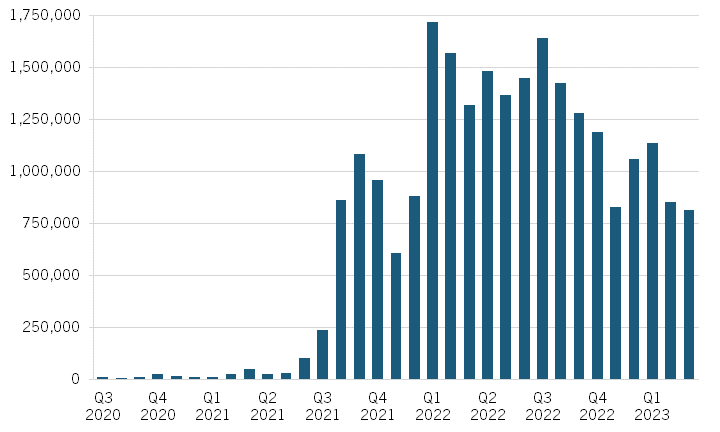

There are a variety of use cases for NFTs, including in areas such as digital art, collectibles, gaming, entertainment, fashion, and more. Many NFT use cases are still in their early stages, and while many Americans have heard of the technology, they still might not understand exactly what it is, and most have not purchased one.[7] In addition, the inability for most consumers to purchase NFTs with credit cards, rather than cryptocurrency, holds back broader adoption.[8] But the technology remains popular among early adopters. As shown in figure 1, the number of NFTs bought and sold on the popular NFT exchange OpenSea has soared since early 2021, but has decreased some over the past year, likely due to significant declines in cryptocurrency markets during that period.

Figure 1: Number of monthly NFT transactions on OpenSea, July 2020–March 2023[9]

Digital Art

One of the most notable use cases for NFTs is to buy and sell digital art. NFTs act as a digital certificate of ownership that makes it possible to easily buy and sell art online. Artists can attest to the authenticity of their works, as well as prove that they are only selling a limited number of copies, which can create more value for the buyer. Perhaps most importantly, NFTs can contain smart contracts, and these contracts can be designed such that the artist receives income from not only the initial purchase but also royalties for all future trades. This feature is especially appealing to artists who may become more commercially successful in the future, as the smart contract ensures they receive additional compensation as the value of their work appreciates over time. Buyers can display their NFTs, including on social media, such as with Twitter’s NFT Profile Pictures feature, which verifies that the Twitter user owns the NFT on display by connecting to their crypto wallet.[10]

The NFT art market has seen rampant speculation. In March 2021, Mike Winkelmann, a digital artist known as Beeple, sold an NFT for $69.3 million at Christie’s auction house, a significant record, especially since only a few months earlier the most the artist had ever sold a print for was $100.[11] The work, a digital collage titled Everydays: The First 5000 Days, inspired both artists and collectors, as well as speculators, to take note of the impact of NFTs in the art world. However, speculators have dominated the market for NFT art, buying these digital assets with the hope of selling them later for a profit, rather than because they want to own a particular piece of art. This dynamic has resulted in significant price volatility, which discourages more-traditional art collectors.

Collectibles

NFTs make it possible to create digital collectibles. Since anything, digital or physical, can be tokenized, the possibilities are nearly endless. For example, in December 2021, U.S. Senate candidate Blake Master sold 99 NFTs based on the cover art from his book Zero to One, raising over half a million dollars from this fundraiser in 36 hours.[12] But, as with digital art NFTs, there is also much speculation in the NFT collectibles market. Twitter founder Jack Dorsey famously sold an NFT of his first tweet for $2.9 million in March 2021. However, when the man who bought the NFT tried to resell it a year later, the top offer was only a few thousand dollars.[13]

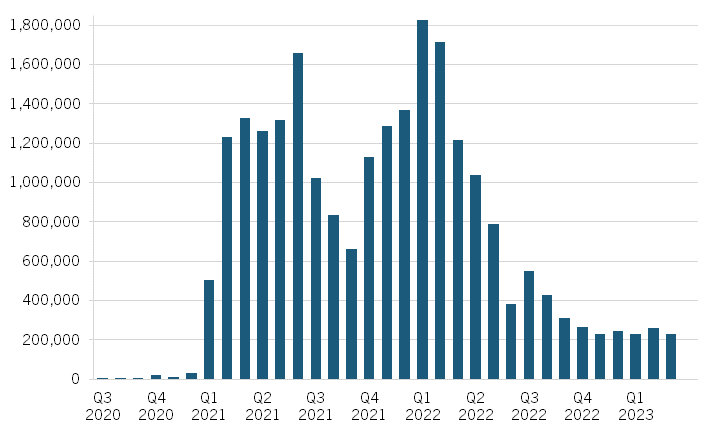

NFT collectibles have seen mixed success. For example, NBA Top Shot is an officially licensed collection of NFTs from the National Basketball Association (NBA) and the Women’s National Basketball Association (WNBA). Created in October 2020 by Dapper Labs in partnership with the NBA, these NFTs are essentially virtual basketball trading cards.[14] Each NFT captures a video clip of a player, called a “moment,” from a game, such as Lebron James dunking during a fastbreak. While, at its peak in February 2021, NBA Top Shot generated approximately $224 million in monthly sales, those sales have significantly declined since then, averaging about $3 million per month in early 2023.[15] The decrease is due to both lower average prices per transaction and a lower number of transactions. As shown in figure 2, the total number of monthly transactions averaged less than 300,000 between October 2022 and March 2023.

Figure 2: Number of monthly NBA Top Shot transactions, July 2020–March 2023[16]

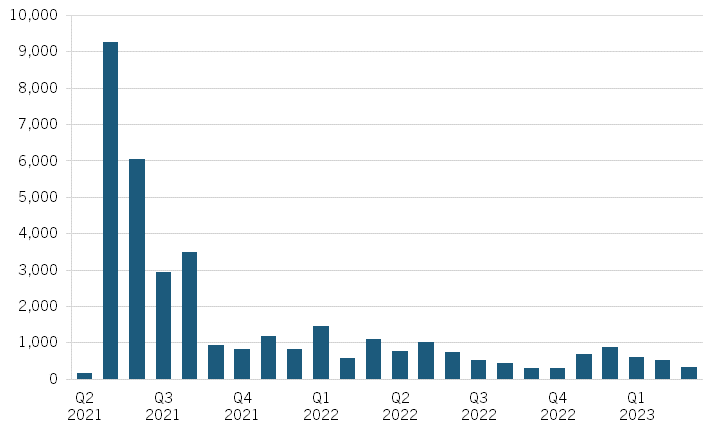

Another popular NFT collection, which has subsequently spurred many copycats, is Bored Ape Yacht Club (BAYC). Created in April 2021 by Yuga Labs, the collection consists of 10,000 NFTs that represent different cartoon-like apes with around 170 different traits, such as clothing, facial expressions, and backgrounds. Ownership of a BAYC NFT entitles the owner to commercial usage of their ape avatar, as well as membership in a virtual social club.[17] The popularity of BAYC surged in part because a number of high-profile celebrities, including Justin Bieber, Serena Williams, Madonna, Gwyneth Paltrow, Paris Hilton, Jimmy Fallon, Kevin Hart, DJ Khaled, and Steph Curry, were linked to the NFT collection.[18] As shown in figure 3, the number of monthly transactions has significantly declined since its peak.

Figure 3: Number of monthly BAYC transactions, April 2021–March 2023[19]

Some brands are using NFTs for physical collectible items. For example, BlockBar is an online platform that creates NFTs for luxury liquor brands. The NFT owner can redeem the NFT for the physical bottle. Users can buy and sell the NFTs, each of which corresponds to specific physical bottles the company stores in its warehouse. By keeping all this information on the blockchain, collectors can trade bottles without the associated shipping costs and delays or concerns about authenticity.[20]

Gaming

Another popular use of NFTs has been for gaming. As mentioned previously, CryptoKitties was one of the first major NFT-based games to gain widespread use. In this game, players can collect, breed, and trade virtual cats. Each cat has certain attributes, which can be passed on through breeding, with different levels of rarity. Launched in November 2017, the game became so popular that within a month, it accounted for 11 percent of the traffic on the Ethereum blockchain and had generated $4.5 million in sales.[21] While the CryptoKitties mania has passed, as of March 2023, there were approximately 2 million CryptoKitties NFTs in existence with 119,000 owners.[22]

CryptoKitties paved the way for more-advanced NFT games. Axie Infinity is another NFT-based digital pet game. In this game, created by the Vietnamese company Sky Mavis in March 2018, players can collect, breed, raise, and battle digital pets called “Axies” (inspired by the axolotl, a type of salamander), as well as buy virtual land. Similar to other card-battler games, players can battle each other in real time and earn rewards using an in-game cryptocurrency. Like many NFT games, Axie Infinity is a “play-to-earn” game in which players can cash out their rewards. Early adopters have also created guilds that rent out their Axies to other players who cannot afford their own, in exchange for part of their earnings. At its peak, in January 2022, Axie Infinity had nearly 2.8 million active monthly players. Its popularity has since declined. In March 2023, the game had approximately 389,000 active monthly players.[23]

However, other games have kept players engaged. One of the most popular ones is Alien Worlds, a sci-fi game in which players can earn NFTs and cryptocurrency as they mine, own, and rent virtual land, complete missions, and participate in planetary politics.[24] Other popular NFT games include Benji Bananas (a play-to-earn action-adventure game) and Splinterlands, an NFT-based online collectible card game.[25]

Entertainment

The entertainment industry has experimented with using NFTs to offer consumers unique offerings, as they offer a number of potential opportunities for entertainers, such as creating NFT-based tickets that limit scalping—the practice of buying tickets to an entertainment event in order to resell them at inflated prices—by setting a maximum price in the smart contract and ensuring authenticity by allowing anyone to trace its origins on the blockchain. Entertainers can also use NFTs as rewards, such as providing an exclusive NFT to attendees of a particular event as a type of virtual memorabilia.

Kings of Leon was the first major band to release an album as an NFT in March 2021. The band partnered with YellowHeart, a U.S.-based ticketing company, to create different types of NFTs for its album When You See Yourself. One NFT was for a special digital album. The band sold the token for $50, and buyers received not only the token but also a digital download of the album, access to exclusive album cover art, and a limited-edition vinyl of the album. The band limited sales of this NFT to two weeks, after which it would no longer mint additional ones.[26] The band also auctioned six “golden ticket” NFTs that grant each owner four front-row seats to one show in every Kings of Leon headlining tour for life, along with a VIP experience that includes a personal driver, a concierge at the concert, and an opportunity to hang out with the band.[27]

Warner Bros has begun experimenting with NFTs for films. In October 2022, the studio partnered with Eluvio, a California-based start-up, to release NFTs for The Lord of the Rings: Fellowship of the Ring. The NFT was the studio’s first step in building its “WB’s Movieverse,” an online marketplace wherein users can buy and sell NFTs for its films.[28] The studio created two versions: a $30 “Mystery Edition” and a $100 “Epic Edition.” For the Mystery Edition, NFT owners receive access to a 4K extended edition of the film, along with hours of special features, image galleries, augmented reality collectibles, and an interactive navigation menu tied to a specific location-based theme from the film (i.e., The Shire, Rivendell, or Mines of Moria). The Epic Edition includes everything in the Mystery Edition, plus additional image galleries. Much like collectible DVDs, Warner Bros offered only a limited number: 999 copies of the Epic Edition, and 10,000 of the Mystery Edition.[29]

Fashion

Fashion brands can use NFTs to sell virtual clothing, shoes, bags, jewelry, and more. Consumers can purchase these items for use in the metaverse, including virtual games and other immersive experiences. Leading fashion brands earned $245 million from NFTs in 2022. Nike, which acquired the virtual sneakers company RTFKT in 2021, was a major player, earning $184 million in revenue in 2022, with half of that from direct sales and the other half from royalties from resellers.[30] Other top earners include the luxury fashion brands Dolce & Gabbana, which made $25.6 million; Tiffany & Co., which made $12.6 million; and Gucci, which made $11.6 million.[31]

Dolce & Gabbana sold NFTs that combined virtual fashion with physical items. Its first NFT collection, which sold at auction for a total of $5.7 million, included five physical items (which come with virtual counterparts) and four purely virtual ones. The most expensive of these was The Doge Crown, a headdress inspired by the Doge’s Palace in Venice and embellished with 7 sapphires and 142 diamonds.[32] Notably, the owner received not only the physical item and a digital 4K replica but also a number of experiential benefits, including access to fashion shows and a private tour of the Dolce & Gabbana studio in Milan.[33]

Consumers can also use NFTs to trade physical fashion items. The online retailer StockX offers an Internet marketplace for people to buy and sell shoes, apparel, and other products from popular brands. The company receives the items, verifies their authenticity, assesses their quality, and then lists the products. The company now also creates NFTs that allow users to buy and sell certain physical products without taking actual possession of the items. Trading an NFT instead of the physical item allows a product to trade hands multiple times with minimal costs.[34]

Key Policy Issues

NFTs raise several policy issues lawmakers and regulators are still grappling with. These include appropriate financial regulations, IP rights, consumer protection, energy consumption, privacy, and content moderation. This section describes some of these key issues, and the following section describes specific policy actions taken in the United States.

Financial Regulation

Some NFTs are likely subject to financial regulation, but it is not always clear which rules apply or which regulator has jurisdiction. Generally, different rules apply depending on whether regulators classify NFTs as securities, commodities, or some other type of asset class. Securities are investment instruments, such as stocks and bonds, intended to produce returns from a common enterprise. Commodities are raw materials, such as oil, wheat, or gold, that are used as input to produce other goods or services; investors can speculate on the price of commodities with futures contracts. Other asset classes also exist, such as currency and real estate, and can be used both to store value and for speculation. Given the diversity of NFTs and applications of the technology, the rules for NFTs may depend on context.

Financial regulations may impose several important obligations on those buying and selling NFTs. Policymakers design financial regulations for a variety of reasons, including for market efficiency and stability, consumer and investor protection, and to prevent illegal activity.[35] For example, NFTs may trigger anti-money laundering (AML) and know-your-customer rules to prevent criminals and terrorists from using NFTs to perform illicit transactions or engage in fraud. Similarly, those offering NFTs may be subject to certain transparency and reporting obligations to prevent money laundering and tax evasion, as well as to adhere to government sanctions.

IP Rights

NFTs have created several questions around IP rights. In particular, there are sometimes disputes over who has the right to create an NFT about some other asset. For example, the studio Miramax sued the filmmaker Quentin Tarantino in 2021 after the latter created an NFT based on the film Pulp Fiction. Tarantino argued that the NFT was based on the screenplay, which he owns the rights to, whereas Miramax argued that his NFTs would infringe on its rights to the film itself.[36] The parties eventually settled the dispute out of court in 2022 without revealing the terms of the settlement.[37]

Or consider the myriad IP issues that have plagued Yuga Lab’s BAYC NFT project. In most cases, buying an NFT does not confer any IP rights. However, Yuga Labs explicitly states that its NFT owners receive all commercial usage rights associated with the Bored Ape image tied to their NFT. For example, actor Seth Green bought a Bored Ape and stated his intention to develop a television series around the character. When someone reportedly stole his NFT, many speculated that he would be unable to continue the project because he no longer owned the IP rights. He eventually paid to reacquire the NFT but has not announced any further details about his television project.[38]

Indeed, the IP issues around BAYC are even more complex. Yuga Labs has not registered copyright protection for its NFTs, and indeed, because each of the 10,000 ape images is algorithmically generated, the U.S. Copyright Office may not grant them copyright protection because they do not involve direct human authorship.[39] If these NFTs do not have copyright protection, their owners may ultimately find them to be less valuable. BAYC has also spurred several copycat projects, including some NFT collections that are nearly identical. While Yuga Labs has not pursued copyright infringement claims against imitators, it has pursued trademark infringement claims.[40]

Conflicts can also arise between digital IP rights and physical IP rights. For example, IP law gives rightsholders the right to use their registered trademark and prevent others from using it without authorization. However, once an item has been sold, the rightsholder no longer has the right to control its distribution, a principle referred to as the “first sale doctrine.” In other words, entities other than the rightsholder are allowed to resell products. The conflict arises when an online retailer creates an NFT of a physical good it has legally purchased and that confers ownership of that product and then sells that NFT. Is the NFT a new digital asset that infringes on the trademark owner’s rights? Or is it a lawful use protected by the first sale doctrine, such as when a seller on eBay shows a photo of a product bearing a trademark? This question is at the heart of a lawsuit between the online marketplace StockX and Nike.[41] In other cases, the distinction is clearer. For example, the luxury fashion brand Hermès successfully sued an artist who developed a “MetaBirkins” NFT collection for trademark infringement of its Birkin handbag.[42]

Consumer Protections

Regulators often try to protect consumers from unfair, deceptive, or abusive practices, and these are serious issues for consumers who purchase NFTs. For example, the NFT marketplace OpenSea reported that after it had made it possible for creators to offer NFTs on its marketplace without paying any initial listing fees, 80 percent of the items created using that feature were “plagiarized works, fake collections, and spam.”[43] Consumers who buy fraudulent NFTs can suffer heavy losses. For example, one individual spent $300,000 on an NFT from someone who claimed to be the street artist Banksy, only to later discover that the artist had no involvement with the NFT.[44] Other buyers have similarly fallen victim to scammers who have impersonated other artists to sell fake NFTs, although few on such a large scale.

In addition to counterfeit NFTs, consumers face other NFT scams, particularly those designed to defraud individuals purchasing NFTs as an investment. One method is rug pull scams, wherein fraudsters sell NFTs for a project they have no intention of completing. After selling the NFTs, the fraudsters shut down the project, transfer all funds, and disappear, leaving those who purchased the NFTs with nothing of value.[45] Some scams involve old-fashioned Ponzi schemes, where money from new investors goes to pay returns to earlier investors. Some of the ways these schemes draw in new money is by selling NFTs.[46] Another method scammers use is wash trading, in which scammers sell NFTs to wallets that they control, making the NFT collection appear more popular and thus more valuable.[47] This type of scam is similar to pump-and-dump schemes in which fraudsters promote an asset with false claims to artificially inflate its price and then quickly sell the asset, leaving the new investors with a worthless asset.[48] Pump-and-dump scams are especially common with new tokens.[49]

Scammers can also use cyberattacks, such as phishing attacks or malware, to obtain credentials to a victim’s crypto wallet and then steal their NFTs. The anonymity of blockchain transactions, combined with the ability of scammers to quickly transfer assets to multiple wallets and then exchange them for other cryptocurrencies, makes it incredibly difficult, if not impossible, for victims to regain stolen digital assets. One cryptocurrency risk management firm estimates that between July 2021 and July 2022, more than $100 million of NFTs were publicly reported stolen.[50]

Energy Consumption

Many policymakers have concerns about the energy consumption of blockchain technologies.[51] Most of this has to do with stems from blockchain protocols, such as Bitcoin, that use a proof-of-work protocol. Before participants can confirm new transactions to the blockchain, they must first solve a mathematical proof of work (PoW). The difficulty of the proof can vary based on the quantity and efficiency of the miners. For example, Bitcoin is structured such that the average time to find a new block is approximately 10 minutes.[52] In theory, miners would not spend more on these activities than the economic value they generate (otherwise, it would be a money-losing proposition). However, as the price of many popular digital cryptocurrencies is likely highly inflated due to speculation, there is a large financial incentive to engage in mining. As more miners participate, the PoW difficulty increases, and thus the overall energy use increases.[53] Generally, if the price of Bitcoin rises, energy usage will increase, and if the price of Bitcoin drops, energy usage will fall. In addition, the payout to miners halves approximately every four years, so unless the price of Bitcoin doubles in that period, miner revenue, and thus the incentive to mine and resulting energy use, will decrease as well.

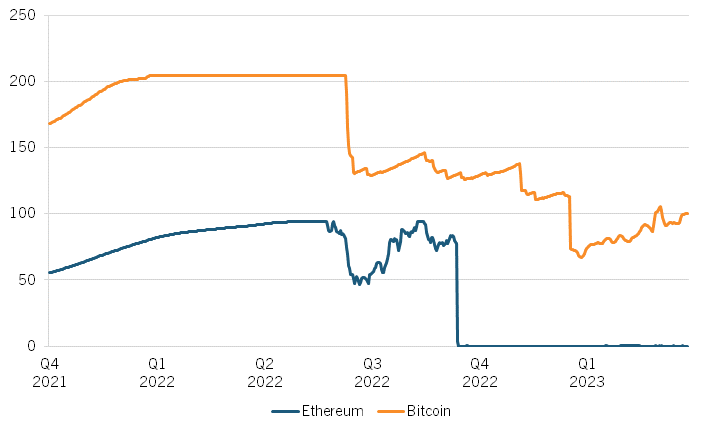

However, most NFTs do not use the Bitcoin blockchain. As previously noted, many of the earliest projects use Ethereum. Ethereum was initially used a PoW consensus mechanism as well, but on September 15, 2022, the network converted to an alternative consensus mechanism known as “proof-of-stake.” Proof-of-stake protocols require multiple “validators” in the network to verify that blocks are legitimate before they add them to the blockchain. Validators are chosen randomly, but each one must stake a certain amount of coins, and those who risk greater amounts have a higher chance of being selected as a validator. Validators risk losing their stake if they attempt to cheat. Using proof-of-stake significantly reduces the amount of computational work necessary. As a result, as shown in figure 4, the Ethereum network has reduced its energy consumption by 99.84 percent, significantly more so than has Bitcoin.[54] Other popular blockchain networks for NFTs, including Solana and Polygon, similarly do no use PoW and have significantly lower energy consumption compared with Bitcoin.[55]

Figure 4: Bitcoin and Ethereum energy usage (estimated TWh per year), October 2021–March 2023[56]

Privacy

NFTs raise a number of privacy issues policymakers may want to address. One issue is even though blockchain allows for anonymous transactions, it is sometimes possible to identify the person behind a particular transaction because transactions on the blockchain are linked to crypto wallets. For example, someone buying or selling an NFT will use a crypto wallet to complete the transaction. Crypto wallets do not store NFTs, as these tokens are stored on the blockchain. Instead, when purchasing an NFT, the blockchain entry for that NFT will be updated to reflect the unique public identifier of the new owner’s crypto wallet.

Sometimes the individuals themselves reveal their identities intentionally. For example, a new NFT project may reveal the identities of the project founders, in part to increase trust in the project. However, other times, individuals may reveal their identities unintentionally. For example, if an individual links an NFT profile picture to their social media account, anyone can inspect the blockchain and find other transactions associated with that wallet. Because these details may be linked to someone’s identity, some privacy laws may treat this information as personally identifiable information. This information on the blockchain may even reveal sensitive information, such as location information. As described earlier, some events may issue proof-of-attendance NFTs to attendees, which serve as a virtual ticket stub and, depending on the event, may identify somebody’s location at a specific point in time.[57] Finally, NFTs could themselves potentially contain personally identifiable information, and since information on the blockchain is immutable, the existence of the NFT can conflict with privacy laws that give individuals the right to erase information about them.[58]

Content Moderation

NFTs also raise questions about content moderation, especially for online platforms that allow users to buy and sell these tokens. NFTs can contain illegal, harmful, or prohibited content. These NFTs may violate an online platform’s terms of service, and policymakers will likely have questions about how effectively they monitor their platforms and enforce their policies. OpenSea, a popular marketplace for NFTs, reported in 2022 that it was taking down 3,500 NFT collections every week that violated its policies around copyright and counterfeits.[59] Laws that limit intermediary liability, such as Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, protect online platforms from liability for the speech of others.

U.S. Policy Developments

There have been a number of recent policy developments that have shaped the U.S. approach to NFTs, including an executive order on digital assets, important developments at key regulatory agencies, tax implications, and criminal prosecutions by law enforcement.

Executive Order on Digital Assets

On March 9, 2022, President Biden issued an Executive Order (EO) on Ensuring Responsible Development of Digital Assets.[60] The EO represented the first whole-of-government approach in the United States to cryptocurrencies and other digital assets. It outlined six major objectives: 1) protect consumers, investors, and businesses; 2) promote U.S. and global financial stability and mitigate risks to financial systems; 3) combat and prevent illicit finance and national security risks posed by misuse of digital assets; 4) reinforce U.S. leadership in the global financial system and in technological and economic competitiveness, including in payment innovations and digital assets; 5) promote access to safe and affordable financial services; and 6) support responsible technological innovation in the development and use of digital assets.

The EO set in motion multiple activities in many federal agencies to develop and coordinate policies on digital assets across all of these objectives, including establishing a U.S. Central Bank Digital Currency. The EO also directed federal agencies to produce reports on key issues and increase engagement on these issues with foreign partners in international forums and through bilateral partnerships. By September 2022, the participating agencies had transmitted nine of these reports to the president, which outlined an overall U.S. approach to digital assets, as well as detailed recommendations in key areas.[61] For example, the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy issued a series of recommendations on how to responsibly develop digital assets in light of the U.S. government’s climate objectives.[62] In terms of the overall framework, a few main themes emerged: 1) the Federal Reserve will continue its research and experimentation to develop a U.S. Central Bank Digital Currency; 2) regulators will increase enforcement of existing laws to protect consumers, investors, and businesses; 3) the administration will expand its interagency efforts to combat illicit activity from digital assets, such as money laundering and financing terrorism; and 4) the administration will promote research and development in digital assets to help U.S. firms gain traction in global markets.[63]

Regulatory Agencies

There is significant regulatory uncertainty about NFTs, in part because they may be subject to multiple regulators. These regulatory agencies, including the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), as well as a number of other regulators, have potential oversight and impact on NFTs in the United States.

Securities and Exchange Commission

The SEC regulates securities, so a key question is whether an NFT qualifies as a security. As the director of the SEC’s Division of Enforcement has stated, “We are not concerned with labels, but rather the economic realities of an offering.”[64] NFTs, as well as other digital assets, may qualify as securities if they meet the so-called “Howey test.” According to this standard, a digital asset may qualify if it involves “investment of money in a common enterprise with a reasonable expectation of profits to be derived from the efforts of others.”[65] If NFTs qualify as securities, then these transactions would fall under U.S. securities laws, which means sales must be registered with the SEC, sellers would have to register as broker-dealers, and online marketplaces would have to register as securities exchanges. Federal securities laws also require those paid to promote securities to disclose this information. For example, Kim Kardashian paid $1.26 million in 2022 to settle SEC charges that she unlawfully touted a crypto asset security on social media.[66]

Many NFTs, such as virtual pets, likely do not meet this standard. Even if they appreciate in value over time, most of these NFTs are comparable to fine art or real-world collectibles, which the SEC does not regulate as an investment vehicle. However, some NFTs likely would qualify as securities. For example, NFTs that generate passive income for their owners from underlying assets, whether those assets or physical or digital, would likely fall under the SEC’s jurisdiction.[67]

The SEC appears to be looking more closely at NFTs. The agency nearly doubled the size of its enforcement unit for crypto markets, expanding to 50 dedicated positions in May 2022. The renamed “Crypto Assets and Cyber Unit” is tasked with investigating securities laws violations related to NFTs, as well as other crypto asset offerings, crypto asset exchanges, crypto asset lending and staking products, and more.[68] According to news reports, the SEC has issued subpoenas to investigate multiple NFT projects. Since some of the NFT projects are anonymous, the SEC must issue subpoenas through social media sites such as Twitter and Discord.[69] Notably, Yuga Labs, maker of the popular Bored Ape Yacht Club, is one of the companies SEC is investigating.[70]

The SEC may also consider some fractionalized NFTs (F-NFTs) to be securities. F-NFTs allow a single NFT to be divided up so that multiple individuals can pool their resources and share ownership. This division is appealing to those who may not be able to purchase an NFT because of its high cost or want to spread the potential risk of investing in NFTs across multiple items. Although F-NFTs are linked to an NFT, most F-NFTs are themselves not actually NFTs. Instead, they represent fungible fractional shares of ownership of an NFT.[71]

The SEC has also signaled that staking-as-a-service providers might be treated as securities. These providers allow users to lend their coins to others, who pool them to compete for rewards on proof-of-stake blockchains. As noted previously, many blockchains now use proof-of-stake as an alternative consensus mechanism to PoW. The SEC considers these types of arrangements to be securities.[72] Since some NFT games allow staking with an in-game cryptocurrency, as well as renting and lending digital assets, these could potentially fall under SEC’s authority.

Commodity Futures Trading Commission

CFTC regulates the derivatives market in the United States. While historically focused on futures contracts, options, and swaps in the agricultural sector, CFTC has emerged as a key regulator for the crypto industry.[73] Both the SEC and CFTC appear to agree that bitcoin is a commodity, but have expressed mixed views on whether ether or other cryptocurrencies are also commodities.[74] But even if CFTC regulates some cryptocurrencies, it will not necessarily regulate NFTs directly, since NFTs do not share the properties of commodities (in particular, commodities typically are fungible). Any digital assets CFTC considers commodities would have to adhere to the Commodity Exchange Act, a law that would impose rules on deceptive and manipulative trading as well require that any margin trading occur on registered derivatives exchanges.[75]

Office of Foreign Assets Control

In the U.S. Treasury Department, OFAC administers and enforces economic sanctions against countries and individuals, such as terrorists and narcotraffickers.[76] U.S. entities must comply with U.S. sanctions regardless of whether a transaction uses fiat currency or cryptocurrency.[77] As of April 1, 2023, OFAC listed more than 1,000 crypto wallet addresses on its list of sanctioned individuals.[78] Of these, 761 were for Bitcoin wallets and 252 were for Ethereum ones.[79] By placing these crypto wallets on its sanction list, OFAC makes it unlawful for someone in the United States to do business with them, such as purchasing NFTs held by those wallets. U.S.-based NFT traders and marketplaces must ensure that they do not engage in, or facilitate, NFT transactions involving the sanctioned addresses.[80]

Financial Crimes Enforcement Network

The Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) is a bureau of the U.S. Department of Treasury responsible for safeguarding the financial system from illicit use. In particular, it enforces federal anti-money laundering and counter-terrorism financing (AML/CFT) rules as part of the Bank Secrecy Act.[81] In 2022, FinCEN released a study on how illicit actors use trade in works of art to evade money laundering restrictions. As part of this study, FinCEN highlighted how the emerging digital art market, including NFTs, can be used for illicit purposes and how applying AML/CFT recordkeeping and due diligence requirements could mitigate these risks.[82]

Additional Regulators

There are additional regulators that may have some impact on digital assets generally or NFTs specifically. These include the following:

▪ Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC): OCC is an independent bureau in the Treasury Department that regulates and supervises banks. It is primarily focused on financial stability, including liquidity risks from banks holding digital assets as well as the stability of stablecoins (cryptocurrencies whose value is tied to a fiat currency).[83]

▪ Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB): CFPB enforces consumer financial protection laws to protect Americans from errors, theft, and fraud. As part of its remit, it collects and tracks consumer complaints, including those about digital assets. Between October 2018 and September 2022, CFPB received approximately 8,300 such complaints, with 40 percent being about crypto fraud and scams.[84]

▪ Federal Trade Commission (FTC): The FTC is responsible for enforcing consumer protection laws prohibiting unfair and deceptive business practices. It provides guidance to consumers about crypto scams and collects data from law enforcement about reported fraud, identity theft, and related issues, including those involving the use of cryptocurrency.[85] The FTC also provides oversight of truth-in-advertising practices, including disclosure requirements for endorsements and testimonials, which are prevalent among NFT projects.

▪ Copyright Office and U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO): The U.S. Copyright Office is responsible for issuing copyright registrations and USPTO is responsible for granting patents and registering trademarks. In response to a congressional request in 2022, the two offices have begun a joint study on the IP issues arising from the use of NFTs.[86]

▪ Office of Government Ethics (OGE): OGE oversees the ethics program used across executive branch agencies to prevent financial conflicts of interest. It issued guidance in July 2022 for when government workers should disclose ownership of NFTs and F-NFTs: Filers must disclose holding any NFTs or F-NFTs that exceed $1,000 in value or produce over $200 in income during the reporting period, and must also disclose the purchase, sale, or exchange of any NFTs or F-NFTs when the transaction is over $1,000.[87]

Tax Policy

Transactions involving digital assets can have tax implications for individuals and businesses. All digital assets, including NFTs, are treated as property for tax purposes, regardless of whether they are bought, sold, or traded. Tax rates for NFTs vary depending on context. In general, taxpayers are responsible for taxes on capital gains and losses, as they would for any other property.[88] However, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) has specific rules for collectibles. The IRS’s policy is to treat an NFT as a collectible if the NFT confers ownership or rights to another asset that meets the IRS’s definition of a collectible, such as a gem. Taxpayers are still responsible for paying capital gains on collectibles.[89] In addition, creators who make their own NFTs may treat that revenue as ordinary income.

Taxpayers are obligated to report digital asset activity on their tax returns, including those involving NFTs. The IRS has made enforcement of these rules a priority. In 2019, the IRS sent out more than 10,000 letters to taxpayers as part of its “Virtual Currency Compliance campaign.”[90] More recently, the IRS revised its tax forms for 2022, and a question on digital assets now appears at the top of Form 1040, the primary form used for individual income tax returns.[91]

Businesses also have new reporting obligations. In November 2021, President Biden signed the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, a bipartisan law to increase investment in infrastructure. This legislation includes a provision requiring crypto exchanges to send an annual tax form to the IRS reporting yearly profits or losses from digital assets. The legislation also requires businesses to report to the U.S. government all transactions involving $10,000 or more in digital assets, extending existing rules that apply to cash transactions.[92]

Criminal Enforcement

The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) established the National Cryptocurrency Enforcement Team (NCET) in October 2021. DOJ tasked NCET with pursuing “complex investigations and prosecutions of criminal misuses of cryptocurrency, particularly crimes committed by virtual currency exchanges, mixing and tumbling services, and money laundering infrastructure actors” and assisting in “tracing and recovery of assets lost to fraud and extortion, including cryptocurrency payments to ransomware groups.”[93] NCET is responsible for bringing its own cases as well as supporting U.S. Attorney’s Offices across the country.[94] NCET combined experts from DOJ’s Money Laundering and Asset Recovery Section and Computer Crime and Intellectual Property Section and DOJ appointed the NCET’s first director in February 2022.[95]

DOJ has subsequently brought a number of criminal cases, some of which have focused on rug pull schemes. In March 2022, the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York brought charges against two individuals alleged to have defrauded buyers out of $1.1 million in a scam involving the NFT project “Frosties.” The project promised buyers that the NFTs would provide buyers early access and other rewards and exclusive passes to future seasons in a metaverse game. Instead, once buyers had purchased all the NFTs, the individuals behind the scam immediately shut down the project and transferred all the funds to crypto wallets they controlled.[96] Similarly, in January 2023, the U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of New York brought charges against a French national who allegedly defrauded nearly $3 million from people who purchased Mutant Ape Planet NFTs. As with the Frosties project, this project made several false promises about what NFT buyers would receive, but once it had sold all the NFTs, the perpetrator transferred all the funds to his own crypto wallets without delivering anything to buyers.[97]

DOJ has also gone after individuals for insider trading related to NFTs. In June 2022, the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York indicted a former product manager at OpenSea for an insider trading scheme. DOJ alleged that the former OpenSea employee, who was responsible for selecting which NFTs would be featured on OpenSea’s homepage, used his advanced knowledge to anonymously purchase NFTs before their release and then sell them shortly afterward for a profit.[98] Interestingly, it was other OpenSea users who first identified the suspicious transactions and accused the OpenSea employee of insider trading.[99]

Recommendations

President Biden’s executive order on digital assets has provided a strong foundation for U.S. leadership on forward-looking policies for NFTs that protects consumers, addresses risks, and promotes innovation. But as the technology matures, there is still more the U.S. government can do, including passing legislation to clarify regulatory responsibilities, strengthening enforcement capabilities, simplifying tax compliance, and creating an online hub for the government’s digital asset policies.

Pass Legislation Clarifying Regulatory Responsibilities

Not only do both the SEC and CFTC claim jurisdiction over digital assets, but they also take differing approaches to how to regulate digital assets. This regulatory uncertainty makes it harder for businesses that are developing new products and services for digital assets to operate. For example, regulators should provide more guidance to developers on play-to-earn games to separate out those who are creating legitimate products from those whose business models more closely resemble a pyramid scheme. To resolve these issues, Congress should clarify when each agency has regulatory authority over various types of digital assets and direct the lead regulator to produce clear guidance for compliance, including for crypto exchanges and online marketplaces for digital assets. Either would likely be a sufficiently capable regulator, but clarifying which agency has authority would help ensure that consumers and businesses know where to report potential violations and prevent bad actors from exploiting regulatory uncertainty in order to evade oversight.

Strengthen Enforcement Capabilities

Law enforcement agencies have pursued cases against bad actors involving digital assets, and both DOJ and the SEC have created enforcement bureaus focused on these digital assets. However, no U.S. regulator has yet developed advanced capabilities to detect fraud from analyzing public transactions on the blockchain. Notably, the first two cases brought by DOJ for insider trading of digital assets—one for NFTs and the other for cryptocurrency—were the result of a Twitter user publicly flagging the alleged fraud.[100] While whistleblowers can and should play a role in reporting fraud, historically, regulators have also relied on in-house analytics teams to identify illegal activity from trading activity. Given that this expertise is likely necessary across multiple agencies, including the SEC, CFTC, FinCEN, and IRS, agencies should establish a joint Digital Asset Analysis and Detection Center to develop and house these capabilities.

Simplify Tax Compliance

Given that digital assets are treated by the IRS as property, many transactions involving cryptocurrencies and NFTs can create taxable events. For example, consider someone who wants to buy an NFT. First, they convert some bitcoin and dollars to ether. Each of those transactions are taxable events. Then they purchase the NFT using ether. That’s another taxable event. If they decide to sell or trade the NFT, that is another taxable event. These taxable events can add up, and those who regularly buy, sell, and trade digital assets can quickly find that they have created enormously complex tax reporting obligations for themselves. When these digital assets are analogous to buying and selling securities, this level of record keeping for tax purposes might make sense. But when they are closer to virtual ticket stubs or in-game rewards, it is unnecessary. Complex tax requirements force consumers to use specialized crypto tax compliance software to streamline their compliance, but using these tools can create security risks if consumers connect their crypto wallets. To simplify compliance, Congress should establish a de minimis exemption for transactions below a certain threshold.

Create an Online Hub for Digital Asset Policies

The Biden administration’s executive order kicked off a whole-of-government approach to addressing digital assets. While it is reasonable and appropriate for many agencies to be involved in creating and coordinating policies about digital assets, the average consumer and developer cannot possibly be expected to know where to look to find all the latest guidance from policymakers, especially since much of this information is spread across dozens of agency websites. To address this problem, the administration should create a single, customer-friendly website to serve as a hub of information about federal government resources regarding digital assets, including cryptocurrencies and NFTs, for consumers and businesses.

Conclusion

NFTs represent a growing category of digital assets with a variety of potential uses. However, NFTs raise important policy questions policymakers are still grappling with. Over the past few years, U.S. policy on NFTs has advanced rapidly to address emerging risks and continues to involve multiple regulators and law enforcement agencies. U.S. policymakers will likely continue to resolve unanswered questions, creating more regulatory certainty for the industry and better protection for consumers and investors.

Appendix: Example NFT Metadata for BAYC #599

About the Author

Daniel Castro is vice president of the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation and the director of the Center for Data Innovation. He has a B.S. in foreign service from Georgetown University and an M.S. in information security technology and management from Carnegie Mellon University.

About ITIF

The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) is an independent 501(c)(3) nonprofit, nonpartisan research and educational institute that has been recognized repeatedly as the world’s leading think tank for science and technology policy. Its mission is to formulate, evaluate, and promote policy solutions that accelerate innovation and boost productivity to spur growth, opportunity, and progress. For more information, visit itif.org/about.

Endnotes

[1]. Alan McQuinn and Daniel Castro, “A Policymaker’s Guide to Blockchain” (ITIF, April 30, 2019), https://itif.org/publications/2019/04/30/policymakers-guide-blockchain/.

[2]. William Entriken et al., “ERC-721: Non-Fungible Token Standard,” Ethereum Improvement Proposals, January 24, 2018, https://eips.ethereum.org/EIPS/eip-721.

[3]. “What is IPFS,” IPFS, n.d., accessed March 31, 2023, https://docs.ipfs.tech/concepts/what-is-ipfs/.

[4]. Dapper Team, “The History Of NFTs,” Dapper Blog, September 15, 2022, https://blog.meetdapper.com/posts/the-history-of-nfts.

[5]. CryptoKitties, n.d., https://www.cryptokitties.co/.

[6]. Witek Radomski et al., “ERC-1155: Multi Token Standard,” Ethereum Improvement Proposals, June 17, 2018, https://eips.ethereum.org/EIPS/eip-1155.

[7]. Alex Silverman, “Millennials, Not Gen Zers, Are Driving the Recent Physical and Digital Collectibles Boom,” Morning Consult, April 5, 2021, https://morningconsult.com/2021/04/05/millennials-nfts-collectibles/.

[8]. “Behavior Report – What Do Consumers Want from NFTs?” DappRadar, February 15, 2023, https://dappradar.com/blog/behavior-report-what-do-consumers-want-from-nfts.

[9]. “OpenSea monthly NFTs sold,” Dune.com, n.d., accessed April 1, 2023, https://dune.com/queries/1958394/3234005.

[10]. Sarah Perez, “Twitter launches NFT Profile Pictures — but only for Twitter Blue subscribers,” TechCrunch, January 20, 2022, https://techcrunch.com/2022/01/20/twitter-blue-subscription-users-are-first-gain-access-to-a-new-nft-profile-picture-feature/.

[11]. Jacob Kastrenakes, “Beeple sold an NFT for $69 million,” The Verge, March 11, 2021, https://www.theverge.com/2021/3/11/22325054/beeple-christies-nft-sale-cost-everydays-69-million.

[12]. Emily Brooks, “NFTs propel Blake Masters fourth-quarter fundraising: 40% of $1.38M haul from digital tokens,” Washington Examiner, January 5, 2022, https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/news/blake-masters-nft-fundraising-2021-arizona.

[13]. Elizabeth Howcroft, “Bought for $2.9 million, NFT of Jack Dorsey tweet finds few takers,” Reuters, April 14, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-fintech-nft-tweet-idTRNIKCN2M617P.

[14]. Shaker Samman, “What’s all the fuss bout NBA Top Shot?” Sports Illustrated, March 17, 2021, https://www.si.com/nba/2021/03/17/nba-top-shot-crypto-daily-cover.

[15]. “NBA Top Shot Sales Volume Data, Graphs & Charts,” CryptoSlam, n.d., accessed April 1, 2023, https://www.cryptoslam.io/nba-top-shot/sales/summary.

[16]. Ibid.

[17]. “Welcome to the Bored Ape Yacht Club,” BAYC, n.d., accessed March 30, 2023, https://boredapeyachtclub.com/.

[18]. Sam Tabahriti, “The company behind Bored Ape Yacht Club NFTs is being sued for using celebrities to promote their products,” Business Insider, December 11, 2022, https://www.businessinsider.com/celebrities-named-lawsuit-against-company-behind-bored-ape-nfts-2022-12.

[19]. “Bored Ape Yacht Club,” Crypto Slam, n.d., accessed April 1, 2023, https://www.cryptoslam.io/bored-ape-yacht-club?tab=historical_sales_volume.

[20]. “FAQs: Getting Started,” BlockBar, n.d., accessed March 31, 2023, https://blockbar.com/faq.

[21]. Olga Kharif, “CryptoKitties Mania Overwhelms Ethereum Network's Processing,” Bloomberg, December 4, 2017, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-12-04/cryptokitties-quickly-becomes-most-widely-used-ethereum-app; “CryptoKitties craze slows down transactions on Ethereum,” BBC, December 5, 2017, https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-42237162.

[22]. “CryptoKitties NFT,” NFT Stats, n.d., accessed March 31, 2023, https://www.nft-stats.com/collection/cryptokitties.

[23]. “Axie Infinity Live Monthly Player Count,” Active Player, n.d., March 31, 2023, https://activeplayer.io/axie-infinity/.

[24]. Alien Worlds, n.d., accessed March 31, 2023, https://alienworlds.io/.

[25]. “NFT games with the highest player count in the last 30 days as of November 29, 2022,” Statistica, November 29, 2022, https://www.statista.com/statistics/1266486/blockchain-games-user-number/.

[26]. Tatiana Cirisano, “Kings of Leon NFTs Generate $2M in Sales & Benefit Crew Nation Fund,” Billboard, March 9, 2021, https://www.billboard.com/pro/kings-of-leon-nft-sale-2-million-sales-crew-nation/.

[27]. Samantha Hissong, “Kings of Leon Will Be the First Band to Release an Album as an NFT,” Rolling Stone, March 3, 2021, https://www.rollingstone.com/pro/news/kings-of-leon-when-you-see-yourself-album-nft-crypto-1135192/.

[28]. Charles Pulliam-Moore, “Warner Bros.’ Lord of the Rings NFT ‘experience’ is just The Fellowship in 4K,” The Verge, October 20, 2022, https://www.theverge.com/2022/10/20/23413237/lord-of-the-rings-movie-nft-wb-movieverse-metaverse.

[29]. “Warner Bros. to Sell ‘Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring’ in Limited-Edition NFT Bundles, First for a Major Studio,” Variety, October 20, 2022, https://variety.com/2022/digital/news/lord-of-the-rings-fellowship-of-the-ring-nft-release-1235406247/.

[30]. Maya Ernest, “Nike has already made $185 million off of NFTs,” Inverse, August 24, 2022, https://www.inverse.com/input/style/nike-most-revenue-nft-sales-list.

[31]. Ibid.

[32]. Dana Thomas, “Dolce & Gabbana Just Set a $6 Million Record for Fashion NFTs,” New York Times, October 4, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/04/style/dolce-gabbana-nft.html.

[33]. “The Doge Crown,” UNXD, n.d., accessed March 30, 2023, https://unxd.com/drops/collezione-genesi/the-doge-crown.

[34]. “NFTs,” StockX, n.d., accessed March 31, 2023, https://stockx.com/lp/nfts/.

[35]. “Who Regulates Whom? An Overview of the U.S. Financial Regulatory Framework,” Congressional Research Service, March 10, 2020, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/R44918.pdf.

[36]. Adi Robertson, “Miramax sues Quentin Tarantino over Pulp Fiction NFTs,” The Verge, November 17, 2021, https://www.theverge.com/2021/11/17/22787216/miramax-pulp-fiction-quentin-tarantino-nft-lawsuit.

[37]. Adi Robertson, “Quentin Tarantino settles NFT lawsuit with Miramax,” The Verge, September 9, 2022, https://www.theverge.com/2022/9/9/23344441/quentin-tarantino-pulp-fiction-nft-miramax-lawsuit-settled.

[38]. Sarah Emerson, “Seth Green's Stolen Bored Ape Is Back Home,” BuzzFeed News, June 9, 2022, https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/sarahemerson/seth-green-bored-ape-nft-returned.

[39]. Kyle Barr, “Yuga Labs Claims Its Bored Apes Have Copyright, Even if It Never Filed for Protection,” Gizmodo, January 27, 2023, https://gizmodo.com/yuga-labs-nfts-bored-apes-copyright-1850042639.

[40]. Ibid.

[41]. “Nike v. StockX Case Highlights Many Unanswered Questions About IP and NFTs,” JDSupra, September 7, 2022, https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/nike-v-stockx-case-highlights-many-9205701/.

[42]. Zachary Small, “Hermès Wins MetaBirkins Lawsuit; Jurors Not Convinced NFTs Are Art,” The New York Times, February 8, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/08/arts/hermes-metabirkins-lawsuit-verdict.html.

[43]. Jordan Pearson, “More Than 80% of NFTs Created for Free on OpenSea Are Fraud or Spam, Company Says,” Vice, January 28, 2022, https://www.vice.com/en/article/wxdzb5/more-than-80-of-nfts-created-for-free-on-opensea-are-fraud-or-spam-company-says.

[44]. Mitchell Clark, “Someone paid more than $300K for a fake Banksy NFT — and the scammer gave it all back,” The Verge, August 31, 2021, https://www.theverge.com/2021/8/31/22650594/banksy-nft-scam-pranksy-ethereum-returned-duplicates-art.

[45]. Benjamin Pimentel, “Anatomy of an NFT art scam: How the Frosties rug pull went down,” Protocol, February 24, 2022, https://www.protocol.com/fintech/frosties-nft-rug-pull.

[46]. David Segal, “The Crypto Ponzi Scheme Avenger,” New York Times, November 11, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/11/11/business/crypto-ponzi-scheme-hyperfund.html.

[47]. “Crime and NFTs: Chainalysis Detects Significant Wash Trading and Some NFT Money Laundering In this Emerging Asset Class,” Chainalysis, February 2, 2022, https://blog.chainalysis.com/reports/2022-crypto-crime-report-preview-nft-wash-trading-money-laundering/.

[48]. “24% of New Tokens Launched in 2022 Bear On-Chain Characteristics of Pump and Dump Schemes,” Chainalysis, February 16, 2023, https://blog.chainalysis.com/reports/2022-crypto-pump-and-dump-schemes/.

[49]. “The 2023 Crypto Crime Report,” Chainalysis, February 2023, accessed March 31, 2023, http://chainalysis.com.

[50]. “NFTs and Financial Crime,” Elliptic, 2022, https://www.elliptic.co/hubfs/NFT%20Report%202022.pdf.

[51]. “Climate and Energy Implications of Crypto-Assets in the United States,” The White House, September 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/09-2022-Crypto-Assets-and-Climate-Report.pdf.

[52]. “Frequently Asked Questions,” Bitcoin, n.d., accessed May 2, 2023, https://bitcoin.org/en/faq.

[53]. “Blockchain Charts,” n.d., Blockchain.com, accessed May 2, 2023, https://www.blockchain.com/charts/.

[54]. “Ethereum Energy Consumption Index,” Digiconomist, n.d., accessed April 1, 2023, https://digiconomist.net/ethereum-energy-consumption.

[55]. “Solana’s Energy Use Report: September 2022,” Solana Foundation, September 20, 2022, https://solana.com/news/solanas-energy-use-report-september-2022; “The Merge to Erase 60,000 Tonnes of Polygon’s Carbon Footprint,” Polygon Labs, September 6, 2022, https://polygon.technology/blog/the-merge-to-erase-60000-tonnes-of-polygons-carbon-footprint.

[56]. “Bitcoin Energy Consumption Index,” Digiconomist, n.d., accessed April 1, 2023, https://digiconomist.net/bitcoin-energy-consumption; “Ethereum Energy Consumption Index,” Digiconomist, n.d., accessed April 1, 2023, https://digiconomist.net/ethereum-energy-consumption.

[57]. Matthew Murphy, “NFTs: Privacy Issues for Consideration,” JDSupra, January 27, 2022, https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/nfts-privacy-issues-for-consideration-7804114/.

[58]. Andrea Vittorio, “Blockchain’s Forever Memory Confounds EU ‘Right to Be Forgotten,’” Bloomberg Law, August 3, 2022, https://news.bloomberglaw.com/privacy-and-data-security/businesses-adopting-blockchain-question-eus-strict-privacy-law.

[59]. Lois Beckett, “‘Huge mess of theft and fraud:’ artists sound alarm as NFT crime proliferates,” The Guardian, January 29, 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/global/2022/jan/29/huge-mess-of-theft-artists-sound-alarm-theft-nfts-proliferates.

[60]. “Executive Order on Ensuring Responsible Development of Digital Assets,” The White House, March 9, 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2022/03/09/executive-order-on-ensuring-responsible-development-of-digital-assets/.

[61]. “FACT SHEET: White House Releases First-Ever Comprehensive Framework for Responsible Development of Digital Assets,” The White House, September 16, 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/09/16/fact-sheet-white-house-releases-first-ever-comprehensive-framework-for-responsible-development-of-digital-assets/.

[62]. “Climate and Energy Implications of Crypto-Assets in the United States,” The White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, September 8, 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/09-2022-Crypto-Assets-and-Climate-Report.pdf.

[63]. “FACT SHEET: White House Releases First-Ever Comprehensive Framework for Responsible Development of Digital Assets,” The White House, September 16, 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/09/16/fact-sheet-white-house-releases-first-ever-comprehensive-framework-for-responsible-development-of-digital-assets/.

[64]. “SEC Charges Former Coinbase Manager, Two Others in Crypto Asset Insider Trading Action,” U.S. Securities and Exchange, July 21, 2022, https://www.sec.gov/news/press-release/2022-127.

[65]. “Framework for ‘Investment Contract’ Analysis of Digital Assets,” U.S. Securities and Exchange, March 8, 2023, https://www.sec.gov/corpfin/framework-investment-contract-analysis-digital-assets.

[66]. “SEC Charges Kim Kardashian for Unlawfully Touting Crypto Security,” SEC, October 3, 2022, https://www.sec.gov/news/press-release/2022-183.

[67]. “Reed Smith Guide to the Metaverse – 2nd Edition,” ReedSmith, August 2022, https://www.reedsmith.com/en/perspectives/metaverse/2022/08/is-my-nft-a-security.

[68]. “SEC Nearly Doubles Size of Enforcement’s Crypto Assets and Cyber Unit,” U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, May 3, 2022, https://www.sec.gov/news/press-release/2022-78.

[69]. Insha Zia, “The SEC Doubles Down on NFT Projects with Subpoenas,” Daily Coin, February 22, 2023, https://dailycoin.com/the-sec-doubles-down-on-nft-projects-with-subpoenas/.

[70]. Matt Robinson, “Bored-Ape Creator Yuga Labs Faces SEC Probe Over Unregistered Offerings,” Bloomberg, October 11, 2022, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-10-11/bored-ape-creator-yuga-labs-faces-sec-probe-over-unregistered-offerings.

[71]. Mark Cianci et al., “The Limits of Howey: What the SEC May Be Signaling Through its Approach to NFTs and F-NFTs,” Law.com, November 28, 2022, https://www.law.com/legaltechnews/2022/11/28/the-limits-of-howey-what-the-sec-may-be-signaling-through-its-approach-to-nfts-and-f-nfts/.

[72]. Olga Kharif, Lydia Beyoud, and Allyson Versprille, “What Is Crypto Staking and Why Is the SEC Cracking Down?” The Washington Post, February 11, 2023, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/what-is-crypto-staking-and-why-is-the-sec-cracking-down/2023/02/10/b815851e-a996-11ed-b2a3-edb05ee0e313_story.html.

[73]. “Digital Assets,” CFTC, n.d., accessed March 30, 2023, https://www.cftc.gov/digitalassets/index.htm.

[74]. Andrew Throuvalas, “CFTC Chair Says Ethereum Is a Commodity—Despite Gensler’s ‘Bitcoin Only’ Position,” Decrypt, March 8, 2023, https://cointelegraph.com/news/cftc-declares-ether-as-a-commodity-again-in-court-filing.

[75]. “NFTs: Key U.S. Legal Considerations for an Emerging Asset Class,” Jones Day, April 2021, https://www.jonesday.com/en/insights/2021/04/nfts-key-us-legal-considerations-for-an-emerging-asset-class.

[76]. “Action Plan to Address Illicit Financing Risks of Digital Asset,” U.S. Department of Treasury, September 12, 2022, https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/Digital-Asset-Action-Plan.pdf.

[77]. “Questions on Virtual Currency,” Office of Foreign Assets Control, October 15, 2021, https://ofac.treasury.gov/faqs/topic/1626.

[78]. “Specially Designated Nationals And Blocked Persons List (SDN) Human Readable Lists,” Office of Foreign Assets Control, April 5, 2023, https://ofac.treasury.gov/specially-designated-nationals-and-blocked-persons-list-sdn-human-readable-lists.

[79]. Ibid.

[80]. Jordan Pearson, “The US Government Made It Illegal to Buy These NFTs,” Vice, November 11, 2021, https://www.vice.com/en/article/jgmqvg/the-us-government-made-it-illegal-to-buy-these-nfts.

[81]. “What We Do,” Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, n.d., accessed March 29, 2023, https://www.fincen.gov/what-we-do.

[82]. “Study of the Facilitation of Money Laundering and Terror Finance Through the Trade in Works of Art,” Department of the Treasury, February 2022, https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/Treasury_Study_WoA.pdf.

[83]. “Digital Assets,” Office of the Comptroller of the Currency,” n.d., accessed March 20, 2023, https://www.occ.gov/topics/supervision-and-examination/digital-assets/index-digital-assets.html.

[84]. “Complaint Bulletin: An Analysis of Consumer Complaints Related to Crypto-Assets,” Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, November 2022, https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_complaint-bulletin_crypto-assets_2022-11.pdf.

[85]. “What To Know About Cryptocurrency and Scams,” Federal Trade Commission, May 2022, https://consumer.ftc.gov/articles/what-know-about-cryptocurrency-and-scams; “Consumer Sentinel Network Data Book 2022,” Federal Trade Commission, February 2023, https://www.ftc.gov/reports/consumer-sentinel-network-data-book-2022.

[86]. “Non-Fungible Token Study,” U.S. Copyright Office, n.d., accessed March 31, 2023, https://www.copyright.gov/policy/nft-study/.

[87]. “Financial Disclosure Reporting Considerations for Collectible Non-Fungible Tokens and Fractionalized Non-Fungible Tokens,” U.S. Office of Government Ethics, July 15, 2022, https://www.oge.gov/web/oge.nsf/News+Releases/CCA3DB10F40D247985258883006B5222/$FILE/LA-22-05.pdf.

[88]. “Digital Assets,” IRS, April 6, 2023, https://www.irs.gov/businesses/small-businesses-self-employed/digital-assets.

[89]. “IRS issues guidance, seeks comments on nonfungible tokens,” IRS, March 21, 2023, https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/irs-issues-guidance-seeks-comments-on-nonfungible-tokens.

[90]. “IRS has begun sending letters to virtual currency owners advising them to pay back taxes, file amended returns; part of agency's larger efforts,” IRS, July 26, 2019, https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/irs-has-begun-sending-letters-to-virtual-currency-owners-advising-them-to-pay-back-taxes-file-amended-returns-part-of-agencys-larger-efforts.

[91]. “IRS: Updates to question on digital assets; taxpayers should continue to report all digital asset income,” IRS, January 24, 2024, https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/irs-updates-to-question-on-digital-assets-taxpayers-should-continue-to-report-all-digital-asset-income.

[92]. “SEC. 80603. INFORMATION REPORTING FOR BROKERS AND DIGITAL ASSETS” in Public Law No. 117-58 (11/15/2021), November 11, 2021, https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/3684/text.

[93]. “Deputy Attorney General Lisa O. Monaco Announces National Cryptocurrency Enforcement Team,” U.S. Department of Justice, October 6, 2021, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/deputy-attorney-general-lisa-o-monaco-announces-national-cryptocurrency-enforcement-team.

[94]. Ibid.

[95]. “Justice Department Announces First Director of National Cryptocurrency Enforcement Team,” U.S. Department of Justice, February 17, 2022, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-announces-first-director-national-cryptocurrency-enforcement-team.

[96]. “Two Defendants Charged In Non-Fungible Token (‘NFT’) Fraud And Money Laundering Scheme,” U.S. Department of Justice, March 24, 2022, https://www.justice.gov/usao-sdny/pr/two-defendants-charged-non-fungible-token-nft-fraud-and-money-laundering-scheme-0.

[97]. “Non-Fungible Token (NFT) Developer Charged in Multi-Million Dollar International Fraud Scheme,” U.S. Department of Justice, January 5, 2023, https://www.justice.gov/usao-edny/pr/non-fungible-token-nft-developer-charged-multi-million-dollar-international-fraud.

[98]. “Former Employee Of NFT Marketplace Charged In First Ever Digital Asset Insider Trading Scheme,” U.S. Department of Justice, June 1, 2022, https://www.justice.gov/usao-sdny/pr/former-employee-nft-marketplace-charged-first-ever-digital-asset-insider-trading-scheme.

[99]. Andrew Wang, “OpenSea product chief accused of flipping NFTs using insider information,” The Verge, September 15, 2021, https://www.theverge.com/2021/9/15/22676075/opensea-insider-information-nft-trading-nate-chastain.

[100]. “Three Charged In First Ever Cryptocurrency Insider Trading Tipping Scheme,” U.S. Department of Justice, July 21, 2022, https://www.justice.gov/usao-sdny/pr/three-charged-first-ever-cryptocurrency-insider-trading-tipping-scheme.

Editors’ Recommendations

April 30, 2019

A Policymaker’s Guide to Blockchain

October 3, 2018

ITIF Technology Explainer: What Is Blockchain?

Related

April 24, 2023

New Report Proposes Four NFT Policy Steps to Protect Consumers and Encourage Continued Innovation

April 4, 2023