History Shows How Private Labels and Self-Preferencing Help Consumers

Private label products have been important for consumers and the economy since the 19th century because retailers can sell them at lower prices with greater efficiency than brand-name alternatives. Legislation that prevents retailers from putting their own products front and center—either online or on store shelves—would jeopardize those benefits.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Key Takeaways

Contents

1800–1900: The Rise of Private Labels 3

Private Label Emergence: The Beginning of Lower Price, Better Quality 4

Early Private Labels: Why Implement Them in the First Place? 4

Early Private Labels: Contributions to the Economy 5

1900–1980: Expanding Private Labels 6

Private Label Boom: Variety Encompassing Multiple Product Lines 6

Growth of Private Labels: Every Reason To Implement Them. 7

More Private Labels, More Benefits for the Economy 8

1980–Present: Imagine a Product Without a Private Label Alternative. 10

No Reason to Not Implement Private Label Programs 11

Private Label Economic Benefits Not Stopping Anytime Soon. 12

Proposed Laws Stifling Private Labels and Self-Preferencing 12

Private Label Self-Preferencing Offers Economic Benefits 14

Network Effects Addressing Self-Preferencing Antitrust Concerns 17

Antitrust Enforcement: Exclusion of a Specifically Named Competitor 19

Introduction

Private labels are products retailers produce or acquire from third-party manufacturers to sell under their own brands—typically at lower prices than name-brand products, because retailers order or produce their private labels in bulk and spend less to market them. The first private labels appeared in the 19th century from retailers such as Brooks Brothers and Macy’s. Today, private labels have grown to encompass approximately one-sixth of all consumer packaged-goods sales, including many of the staples we buy regularly and depend on to live our lives, such as groceries, household supplies, and baby- and pet-care products.[1] Since they cost 20 to 30 percent less than brand-name alternatives, private labels improve people’s quality of life by serving as a counter-inflationary force in the economy.[2]

Often, retailers give preference to their own private labels by showcasing them at eye level on store shelves or by listing them higher than other products in online search results. This common practice, known as “self-preferencing,” has drawn scrutiny from critics who claim it is unfair to competing producers and should be remediated through antitrust regulations or legislation. But that analysis is misguided. Carried to its logical conclusion, the attack on self-preferencing amounts to an attack on private labels themselves, because self-preferencing is integral to the private-label model: A big reason retailers can sell their private-label products at lower prices than name-brand products is that self-preferencing allows them to spend less on other forms of marketing. So, if self-preferencing is prohibited, the number of private brands will be reduced, which will hurt consumers and the economy.

Although extreme forms of self-preferencing (e.g., exclusionary conduct) can lead to antitrust violations, retailers want to attract customers; hence, they have no incentive not to sell competing branded products. Antitrust enforcement is only needed when retailers practice exclusionary conduct of a specifically named competitor—and current antitrust laws already address this practice. There is no reason to enact legislation limiting self-preferencing practices. To do so would be to protect for-profit producers at the expense of consumers.

Moreover, while critics of self-preferencing are primarily concerned about it on large online retail platforms, the fastest-growing private label brands are not just from the likes of Amazon, but also from chain grocers and big box retailers such as Aldi, Costco, Sam’s Club, and Trader Joe’s.[3] The over-arching principle guiding today’s digital regulations—“what is illegal offline must also be illegal online”—should also guide the practice of self-preferencing.[4] Practicing reasonable forms of self-preferencing is legal offline; therefore, it is legal online.

History of Private Labels

1800–1900: The Rise of Private Labels

Private labels have offered consumers immense benefits. Regardless of when a private label product emerged, they have only lowered prices and offered quality comparable to branded products. According to Phillip B. Fitzell’s Private Labels: Store Brands & Generic Products, “In the nineteenth century, merchants dealing in the mail order and/or retail-wholesale business recognized the need for lower priced merchandise, but of high quality … Market conditions at the time were not favorable for the consumer … caveat emptor was the watchword for customers.”[5]

Private labels relieved consumers of unfavorable buying conditions from price-hiking peddlers of the nineteenth century to the more expensive branded merchandise in modern-day brick-and-mortar stores and online retailing platforms.

Private Label Emergence: The Beginning of Lower Price, Better Quality

Retailers, or merchants, developed the first private labels in the clothing market as they sought to lower prices while maintaining quality for consumers. As these merchants and retailers found that producing their own clothing brands enabled lower prices for consumers, private labels expanded in the fashion industry, generating product variety and innovations for consumers. For example, the Brooks Brothers, a ready-to-wear clothing store, produced one of the earliest private-label clothing brands; their private-label brands innovated and sold lightweight summer suits and cotton blended shirts as early as the nineteenth century.[6] When department stores emerged in the latter half of the century, they also implemented private labels for various clothing items. The department store Macy’s adopted and has sold private label products since its inception as a retailer.[7] Other department stores quickly followed.

The growth of private labels in the food industry accompanied that of the clothing industry. For example, the chain grocery store Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company (A&P) became one of the first to introduce private-label food products in the form of four private-brand teas: Cargo, High Cargo, Fine, and Finest.[8] Their success influenced other retailers to implement store brands.

Private labels also penetrated other product categories, including medicinal products, stationary, and perfume.[9] Consumers no longer had to navigate the hostile high-priced buying environment, yet they had a wider variety of high-quality products.

Early Private Labels: Why Implement Them in the First Place?

Retailers adopt private labels to gain a strategic advantage over rivals or a financial reward. According to Andres Cuneo et al.’s research,

Studies have revealed that retailers are motivated to develop PLB [private label brands] when they can derive superior benefits, either economic or strategic … PLBs is attractive to retailers when market conditions are set to maximize profits and growth as well as to build differentiation from competitors and improve store image.[10]

Retailers gain greater independence from suppliers when implementing high-quality, low-priced private labels for consumers. Wanamaker, a department store, and Sears, a mail-order house that morphed into a brick-and-mortar store, provide examples of how private brands benefit retailers. Private labels enabled Wanamaker to set strict quality standards and specifications for manufacturers.[11] Alternatively, Sears produced private labels in their facilities and controlled product quality.[12] The drive to gain control of product quality increased consumer welfare because consumers gained more value from better quality private labels sold at a lower price. According to Eric Almquist et. al.’s research, "When customers evaluate a product or service, they weigh its perceived value against the asking price."[13]

Lower costs also incentivized private label implementation. Regardless of whether retailers acquired private label products from manufacturers or produced them themselves, the products’ costs declined compared with non-private label products. The cost reduction primarily stemmed from eliminating middleman wholesalers who inflated prices for the retailer.[14] Essentially, the retailer experienced double marginalization: The manufacturer increases prices for the wholesaler to make a profit, and subsequently, the wholesaler further incorporates this price increase and some percentage of profit they want to receive in the price they quote to retailers.[15]

Early Private Labels: Contributions to the Economy

Private-label products generated three significant economic benefits: lower consumer prices, increased product variety, and enhanced innovation. The cost reduction from eliminating the middleman wholesaler enabled retailers to lower consumer prices.[16] For example, Macy's private label prices were 20 to 50 percent lower than its competitors' prices.[17] Lower consumer prices consequently fostered higher economic welfare. According to R. S. Khemani and D. M. Shapiro, “Consumer welfare refers to the individual benefits derived from the consumption of goods and services. In theory, individual welfare is defined by an individual’s own assessment of his/her satisfaction, given price and income.”[18]

Private labels also augmented economic welfare because they saturated the market with product alternatives. Consumers were no longer constrained to manufacturer-produced, or non-private-label, products. For example, the Brooks Brothers offered consumers a choice between shirts produced to a manufacturer’s specifications and its blended cotton shirts.[19] As a result, the enhanced product variety fostered greater economic welfare.[20]

To demonstrate how private labels increased welfare, consider cotton blended shirts as a novel product—even slightly modified products are new products. Before entering the market, their virtual price is infinite, where demand and quantity are zero. When cotton blended shirts finally appear in the market, their actual price reduces and output increases, resulting in enhanced economic welfare.

Private labels also contributed to economic growth and productivity because they spurred innovation. For example, the Brooks Brothers' private brand innovated the lightweight summer suit with seersuckers and cotton blended shirts in the fashion industry.[21] According to economist Cherroun Reguia, “The innovation output of one company becomes part of the innovation input of another … [thus] improv[ing] existing products and processes [and] contributing to higher productivity.”[22]

Private labels improved consumer welfare, producer welfare, and the overall well-being of the economy. However, antitrust attacks on the efficient practices of retailers that produced the most private labels hindered private label development, despite their contributions.

Stifling Department Store Practices Harmed Private Label Programs

In the late nineteenth century, a growing group of critics attacked department stores with claims that their practices harmed less-efficient competitors. As a result, legislators proposed bills targeting these retailers' efficient practices. For instance, in 1897, New York Assemblyman Barry advocated for legislation limiting department store operations because they had eliminated “numerous previously prosperous tradesmen, and the desolation of an army of employe[e]s.”[23] Barry asserted, “Every corrective provision here sought to be applied to other monopolies may well be used against [the department store]. With an added provision, however, to limit the number of distinctive wares which may be dealt in by one management under one roof.”[24]

This provision called for a limitation to the number of departments, or areas dedicated to a specific product category, these retailers could possess. Such sentiments and advocacy resulted in a New York City Council resolution imposing a $500 annual license fee on each department store department.[25] At the state level, Missouri enacted legislation that imposed a license tax “at not less than $300 nor more than than $500 for each class or group” of products a department store sold.[26] However, these provisions disrupted the development of private labels because department stores could only sell a limited selection of products, thereby having to choose which lines of products they wanted to include and which to eliminate from their stock. If they decided to sell shoes and not kitchenware, they would no longer produce private-label kitchenware, limiting the development of private labels.

These local and state legislations targeting department stores' business practices disrupted private label development and innovations to protect inefficient competitors. Fortunately, the Supreme Court of Illinois and the Supreme Court of Missouri set the precedents in City of Chicago v. Netcher and Wyatt v. Ashbrooke et al., respectively, to overturn these anti-department stores on the basis that they violated constitutional rights.[27] Private labels continued to grow after this backlash subsided.

1900–1980: Expanding Private Labels

Private Label Boom: Variety Encompassing Multiple Product Lines

Private labels expanded in the twentieth century as retailers continued to introduce private label brands, encompassing even more product lines. Despite its declining image, private label development grew at a rapid pace. According to Harper Boyd Jr. and Robert Frank’s research, “In 1958, 84 per cent of all supermarkets reported carrying some private labels. Today this figure is probably closer to 90 per cent, but more important is the fact that many organizations have expanded the number of private labels carried and have intensified their efforts to sell them.”[28]

As a result, supermarket and chain store private labels accounted for approximately 20 percent of annual sales volume in 1965.[29] Private-label products ranged from food products and beauty aids sold at regional chain stores to home electronics and clothing sold at big box stores.[30]

Private labels in the food product industry expanded to perishable and nonperishable goods.[31] A retailer’s top 10 most important private label products were all in the food category.[32] Fifty-two percent of firms listed “regular coffee” as their number one most important private label product; 44 percent listed “oleomargarine” as their second.[33] The 1970s experienced an even more significant expansion of private-label food products. Inflation in the 1970s encouraged private label growth as consumers became more price conscious. Mary Ellen Shoup noted in Food Navigator USA, “As inflation pushes consumers to seek out more affordable products, retailers are seeing a surge in unit sales in certain private label categories.”[34] This statement reflects the inflationary environment of the 1970s.

Nongrocery retailers also responded to consumer demands and expanded their private-label products. For instance, J. C. Penney diversified its private label offerings to encompass home electronics (e.g., television sets and stereo equipment).[35] J. C. Penney, Sears Roebuck, Montgomery Ward, and others sold private-label clothing.[36] Private labels even encompassed jewelry. [37]

Growth of Private Labels: Every Reason To Implement Them

Private labels continued to offer retailers greater independence from branded product manufacturers due to retailers’ control over quality. However, retailers also sought independence due to antitrust attacks on chain stores. For example, in the 1915 A&P v. Cream of Wheat case, the Second Circuit ruled, “Before the Sherman Act it was the law that a trader might reject the offer of a proposing buyer, for any reason that appealed to him … that was purely his own affair … Neither the Sherman Act, nor any decision of the Supreme Court … has changed the law.”[38]

As a result, retailers could not rely on branded product manufacturers to provide consistent product inventory. Hence, they turned to implementing and manufacturing private labels. For instance, chain grocery store Safeway operated nearly 40 manufacturing facilities by the 1930s and produced at least 100 private label brands; similarly, A&P, which lost the Cream of Wheat case, also ramped up its private label manufacturing capabilities.[39]

Private labels continued to lower retailers’ costs. As retailers enhanced their manufacturing capabilities, they also eliminated the outside manufacturer in order to reduce inventory acquisition costs.[40] The Kroger Company eliminated outside bakers when producing private-label bread, cutting costs by 2.4 cents per loaf. [41] The lower costs encouraged retailers to implement private labels and pass the savings on to consumers through lower prices.

Retailers also pursued private labels due to their high sales volume, which is especially critical for large retailers relying on a high stock turn model. For instance, A&P’s private labels represented about 25 percent of sales in the 1960s.[42] More generally, a survey of 16 large retailers reports anywhere between 20 and 50 percent of private label sales.[43] The percentage of private label sales signaled that the product attracted consumers. Lower costs and higher sales encouraged retailers to implement private label brands and generate greater product variety for the consumer’s benefit.

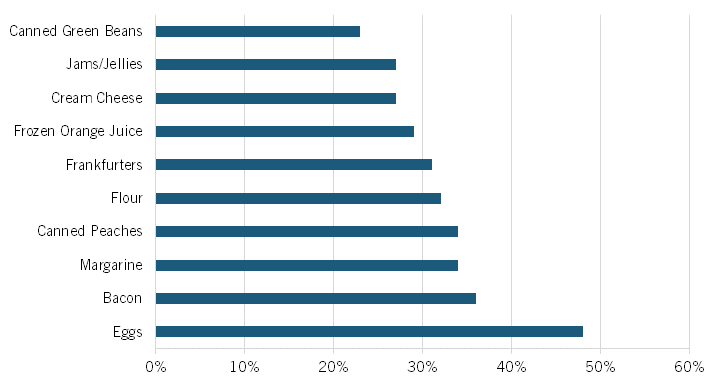

Figure 1: Low and middle-income households’ preference for private labels by product (1971)[44]

Retailers also implemented private labels due to a growing consumer base interested in a low-price, high-quality alternative to national brands and more product variety.[45] For example, Kroger offered at least 10 types of lettuce and exotic fruits and vegetables in response to customer demand for more variety.[46] A survey of 25 products reveals that at least 20 percent of low and middle-income households preferred private-label products over national brands.[47] See figure 1 for an illustration of the percentage of private-label products low- and middle-income families preferred.

More Private Labels, More Benefits for the Economy

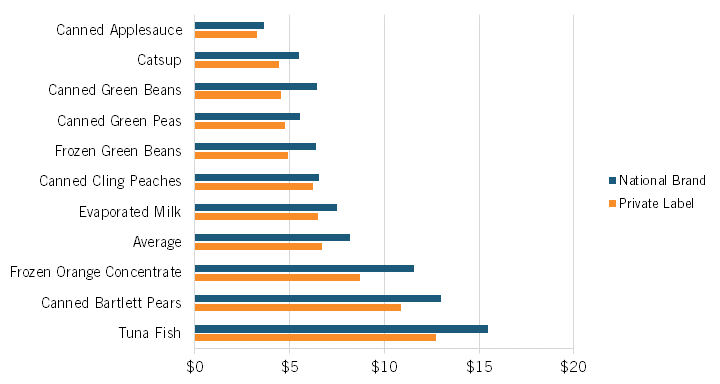

Private labels expanded to include more products, further augmenting their economic contributions: lower prices, increased product variety, and enhanced innovation. Due to lower costs, retailers continued to offer private label products as a low-price alternative to consumers who became increasingly aware of value and savings.[48] A study of 10 products (1967) in the Journal of Consumer Affairs found private labels priced 21.6 percent lower than national brands’ average of $8.16.[49] According to David L. Call who conducted the study, “On average for 10 products, the advertised brand was priced 21.6 percent higher than the private label products with which they competed. This difference in price ranged from a high 41 percent on canned green beans to a low five percent on canned cling peaches.”[50] See figure 2. Despite low prices, most retailers maintained “first-tier, top quality private label lines,” providing consumers with a cost-effective substitute.[51] Consequently, lower prices and quality maintenance augmented consumer and overall economic welfare.

Figure 2: Private label prices compared with national brand prices (1967)[52]

Private labels also continued to foster innovation. Private label implementation encouraged retailers to dedicate large amounts of capital to enhancing and improving their store brand products. For example, Kroger actively sought the development of novel products, and in the 1980s, successfully developed a novel baker’s yeast syrup from whey.[53] Competition between private labels and branded products necessitated product innovation. According to Anne ter Braak and Barbara Deleersnyder’s research, “To stay ahead of competition, retailers can offer an innovative assortment that reflects the latest developments in the industry … retailers may also pursue an imitation strategy and introduce a P.L. [private label] product that contains the innovative feature pioneered by a [sic] N.B. [name brand].”[54]

Moreover, in response to competition, branded product manufacturers innovated novel products to “obtain growth in sales and profits,” thus further stimulating innovation.[55] The product innovations that private labels generated enhanced economic productivity and growth as many became “part of the innovation input to another” industry.[56]

Private label innovations resulting in more product variety continued to increase welfare. For example, while Kroger innovated a new syrup, Acme introduced different quality products—under the names Glenside, Glenwood, Wincrest, and Fireside—within a similar product line, thereby expanding product choices for consumers.[57] Concludingly, private labels cultivated lower prices and more innovation, and increased product choice, thus stimulating growth, boosting productivity, amplifying welfare, and encouraging economic competition.

Robinson-Patman Act: Disincentivizing Private Labels to Protect Competitors

Although private labels continued to foster economic benefits, critics of large retailers, particularly chain stores, nevertheless developed obstacles that harmed private label development in their attempts to protect inefficient retailers. With nearly 141,492 chain stores in 1929, antichain sentiments spread quickly among inefficient retailers and their supporters.[58]

Harsh taxation encompassing at least 20 states illustrated the antichain sentiments of the 1930s. These sentiments against chains that state legislation and courts encouraged fostered a federal legislation that diminished retailers’ incentives to produce private labels, thereby hindering the economic benefits these products offered: the Robinson-Patman Act.

The Robinson-Patman Act, written by senator Joseph Robinson and representative Wright Patman, aimed to protect independent retailers from competition with chain stores—it was known as the Anti-A&P Act.[59] The Act punished large retailers with provisions prohibiting price discrimination. According to the 1998 FTC Secretary of the Commission, Donald S. Clark:

Section 2(a) of the Act requires sellers to sell to everyone at the same price, while section 2(f) of the Act requires buyers with the requisite knowledge to buy from a particular seller at the same price as everyone else. Sections 2(c), 2(d), and 2(e)—as elaborated by the Commission through the FTC Act—prohibit sellers and buyers from using brokerage, allowances, and services to accomplish indirectly what sections 2(a) and 2(f) directly prohibit.[60]

However, the Act also disincentivized private label development in targeting chains’ efficient buying practices. Retailers implementing private labels are responsible for “the added burdens and responsibilities [that] require [them] to seek reduced prices for the private label merchandise, if the program is to succeed financially.”[61] Therefore, private labels only succeed when manufacturers are not constrained to charging all retailers a single price; however, the Robinson-Patman Act explicitly prohibits this action.

The impediment created for private label development is most illustrative in the Federal Trade Commission v. Borden Co. case. Borden Co., an evaporated-milk manufacturer, began offering private label evaporated milk alongside its branded milk in the mid-1950s, resulting in retailers shifting their private label milk business over to Borden.[62] Relying on FTC v. Morton Salt Co., William Jaeger noted that the FTC claimed, “The price differential between the Borden brand and the private label brands constituted a ‘price discrimination’ between purchasers of products of ‘like grade and quality’ under the Robinson Patman Act. The Commission … issued an order directing Borden to cease and desist from discriminating in price between its brand milk and private label milk.”[63]

Despite the Fifth Circuit’s ruling that there was a difference between Borden’s branded and private label milk due to the “commercial significance of the consumer appeal of the Borden label,” the Supreme Court reversed the Fifth Circuit’s decision and affirmed the FTC’s claims.[64]

The decision disrupted the development and innovation of private labels, as manufacturers could not reduce prices for retailers, thereby decimating the cost incentives retailers received when implementing private labels. Fortunately, since the landmark case Brooke Group Ltd. v. Brown & Wiliamson Tobacco Corp., recent cases regarding a violation of the Robinson-Patman Act have rarely been successful.[65] According to Ryan Luch et. al.’s research, “Cases brought by private party plaintiffs were successful … less than 5% for the period 2006–2010. The results indicate a downward trend in the threat of RP. We suggest that this trend stems from an evolvement of antitrust thinking of “competitive harm” or injury to competition.”[66]

Private label implementation continued to expand into the present.

1980–Present: Imagine a Product Without a Private Label Alternative

Today, private labels continue to benefit consumers and the economy. According to a report from DataWeave, “Grocery categories with the highest inflation saw the most private label penetration. Private-label brands also gained volume share in high-inflation food categories such as poultry, meat and frozen foods in 2021.”[67]

Consumers are reducing their brand loyalty in preference of private labels amidst price inflation.

Private Label Products Everywhere: Hard to Think of a Product Line Without Private Label Alternatives

Private labels have continued to expand since the 1980s. Private label sentiments have improved in the last 40 years, and consumers now accept private labels as an alternative to branded products. Consequently, retailers have scaled up their private label production.[68] The 2021 “retail market share of private label brands in the United States was 17.7 percent” and 19.5 percent in 2020, according to Statista.[69]

Grocery retailers are expanding their extensive private-label product lines to include edible and nonedible items. For example, these retailers moved from mostly private-label staple items, such as milk, to nonfood items, such as diapers and health products.[70] In 2021, private label penetration in the online and in-store category was 18 percent (e.g., 20 percent of Whole Foods Market’s products are private labels).[71]

Big box stores’ private-label products extend to electronics, clothing, and food items. For example, in 2020, Walmart debuted its Free Assembly clothing line, and Target debuted its Heyday electronic line in 2018.[72] Brick-and-mortar retailers contribute tremendously to introducing private labels in new product categories.

However, online retailers also contribute to expanding private-label products in this age of digitalization. Online retailers have grown their private label product selections in response to the growing consumer segments interested in branded product substitutes. For example, Amazon introduced its AmazonBasics brand selling batteries and a few other hardware items in 2009; only a decade later, it has developed at least 45 brands and sells approximately 158,000 private label products.[73] These products encompass many consumer goods, including clothing, exercise equipment, and pet products.[74] The sheer range of private label products Amazon sells indicates that private labels proliferate in almost every product category.

No Reason to Not Implement Private Label Programs

Retailers have continued to seek independence from manufacturers, especially as branded product manufacturers raised prices while simultaneously diluting quality in the 1980s.[75] Consequently, many retailers continued to implement private labels to maintain quality while providing a low-price alternative for consumers.[76] Private label quality improved during this period and now rivals, if not exceeds, those of branded products. A Nielsen survey reports, “Sixty-three percent of consumers said they believe that the private label brand quality is as good as name brands and one-third (33 percent) of consumers told Nielsen they consider some store brands are higher quality than name brands.”[77]

Retailers continue to pass on cost savings to consumers through price cutting due to the low cost of private label production. Marketing branded products and developing their respective brands are necessities private labels do not face.[78] Even when retailers market private labels, they control the amount dedicated to advertising, preventing costs from exceeding those of branded products.

Positive consumer sentiments have also encouraged retailers to forge ahead with private label development. According to Berman (2010), 80 percent of United States consumers purchase private labels regularly because they rationalize that private label quality is decent, if not better, than that of branded products.[79] A more recent study by Nielsen corroborates this finding, as 78 percent of consumers in the United States perceive private labels to have increasingly improved qualities.[80] Private brands have gained traction since the 1980s, as consumers have altered their perspective on private label quality.

Moreover, store loyalty and traffic reveal consumer interest in private labels.[81] According to a study of 103 households, consumers’ perception of a store’s private brand impacts their view of the store.[82] According to Colleen Collins-Dodd and Tara Lindley, who conducted the study: “A regression analysis demonstrates a positive relationship between consumers’ perceptions of individual store own brands and their associated store’s image dimensions.”[83]

In other words, when customers perceive a private brand positively, they will also view a store positively, compelling them to return and drive up store traffic. A 2004 study finds that private label implementation enables retailers to attract and serve varying segments of consumers.[84]

Private labels had annual sales of nearly $199 billion in 2021, according to the Private Labels Manufacturing Association.[85] Even with pandemic panic buying taken into account, private labels still generated growth in dollar sales of 5 percent and 6.2 percent in 2018 and 2019, respectively.[86] Hence, private labels are a profitable endeavor for retailers and a bargain for consumers.

Private Label Economic Benefits Not Stopping Anytime Soon

Private labels continue to offer low prices to their consumers. Private label prices are, on average, 20 to 30 percent lower, since retailers do not experience extra costs (e.g., marketing costs) that branded products require.[87] For example, Costco sells its private labels at least 20 percent lower than competing brand names.[88] Costco also eliminated supply chain intermediaries, such as choosing to transport products from production plants to distribution centers rather than relying on distributors, thereby reducing costs and prices.[89]

Private labels further encourage lower prices when they become a substitute for consumers due to price competition. According to Robert Steiner’s research, “Leading advertised brand …‘have had imitators whose price competition has driven down the prices and gross margins of the originators and thereby has brought a limitation on the competition in non-price forms and on the profits of the originating manufacturers.’”[90]

These lower prices translate into increased welfare as more consumers can afford to purchase a product, preventing product market contractions that reduce surplus.[91] Nearly 31 percent of SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) households are loyal to store brands, and 72 percent of private label loyalists actively search for low prices.[92]

Private labels continue to be drivers of innovation, promoting economic growth and productivity. For example, Costco created the square cashew jar to accommodate higher quantities in transporting trucks: A pallet could transport 432 jars of cashews rather than 288.[93] Consequently, this novel product packaging increased Costco’s productivity and introduced a new type of packaging to consumers and retailers. Retailers that replicated this design also boosted their productivity.[94] The overall productivity boost generated economic growth.[95] Additionally, these novel, efficient products and processes replaced inefficient incumbent products and processes, activating what Joseph Schumpeter termed “the gales of creative destruction.”[96]

Private labels continue to offer consumers more choices, once again enhancing welfare. In a study of orange juice quality, participants could not tell the difference between private label and branded orange juice.[97] Hence, private labels are an equal-quality yet low-price alternative that enhances consumer choice. Private-label options activate the variety effect, generating greater economic welfare.[98] According to a yogurt study, private-label yogurts generated 14 percent of producer surplus and 7 percent of consumer surplus in Italy from 2006 to 2007.[99] In other words, families and retailers were better off with the introduction of private-label yogurts. Moreover, welfare also increased for those who purchased national-brand yogurts.[100]

Proposed Laws Stifling Private Labels and Self-Preferencing

Despite the economic benefits private labels offer, critics are again targeting the efficient business practices that incentivize private label development in order to protect competitors from competition. Some critics have even called for the repeal of the consumer welfare standard and the revival of the Robinson-Patman Act to protect inefficient competitors. According to the American Economic Liberties Project, “In truth, a major underpinning of dominant middlemen and retailers is policy, namely government enforcers’ and federal courts’ embrace of a consumer welfare standard that wholly undermined a law Congress passed with the goal of protecting small businesses against the threat of power buyers.”[101]

Today, neo-Brandeisians target the pro-competitive and efficient practice of private-label self-preferencing of online marketplaces. However, prohibiting self-preferencing diminishes the incentive to implement private labels, thereby stifling their economic benefits.

Recently, proposed legislation targeting large tech companies has moved through Congress. Although some bills have reasonable provisions, others solely exist to break up these companies due to their size. Critics claim that these large companies practice unfair methods of competition through self-preferencing and the use of big data in their business decisions; hence, antitrust enforcers should break them up. For instance, now-FTC chair Lina Khan asserted, “Amazon exploits this dual role—marketplace operator and marketplace merchant—in two ways: first, by implementing Marketplace policies that privilege Amazon as a seller and give it greater control over brands and pricing, and, second, by appropriating the business information of third-party merchants.”[102]

As a result of Amazon’s practice of self-preferencing its private labels, Khan called for the structural separation of its marketplace. In other words, Khan claimed that these practices compel ex ante regulations even though self-preferencing incentivizes private labels, and the dual role permits their growth. Neo-Brandeisians’ use of self-preferencing as their reason for targeting large tech companies illustrates that their interest is protecting not consumers but rather inefficient competitors.

In 2021, President Biden furthered the sentiment that competitors are more important than consumers when he released the Executive Order on Promoting Competition in the American Economy, calling for the regulation of online marketplaces because “too many small businesses across the economy depend on those platforms and a few online marketplaces for their survival.”[103] The executive order encouraged the FTC chair to use its “rulemaking authority … [on] unfair competition in major Internet marketplaces,” further emboldening the neo-Brandeisian FTC to pursue antitrust actions against self-preferencing.[104] As they continue to shift the consumer welfare standard toward a producer welfare standard, critics will disrupt private label implementation incentives and harm consumers.

This sentiment that protecting competitors is most important has led to pending bills prohibiting online marketplaces' private label self-preferencing, whether through regulations or structural separation. The Subcommittee on Antitrust, Commercial, and Administrative Law recommended in their Investigation of Competition in Digital Markets the following remedies to address self-preferencing: “Structural separations and prohibitions of certain dominant platforms from operating in adjacent lines of business; Nondiscrimination requirements, prohibiting dominant platforms from engaging in self-preferencing, and requiring them to offer equal terms for equal products and services.”[105]

These recommendations prohibiting self-preferencing and the dual role of marketplaces will reduce private label incentives for retailers, thereby reducing private labels’ economic contributions. Despite the potential economic harm from these recommendations, critics continue their attacks on online marketplaces and their self-preferencing practices.

In 2021, legislators proposed two bills that would harm private label implementation and diminish their economic contributions: the AICOA (S. 2992) and the Ending Platform Monopolies Act (H.R. 3825).[106] The AICOA is most blatant in its attempt to protect inefficient competitors because it directly prohibits online marketplaces’ private label self-preferencing, thereby both diminishing the incentive for retailers to implement private labels and raising consumer prices.[107] The bipartisan Ending Platform Monopolies Act Representative Jayapal (D-WA) introduced does not directly target the self-preferencing of private labels; however, it does prohibit this practice and stifles private labels as it advocates for eliminating “dominant platforms [from leveraging] their control over across multiple business lines.”[108] Both these bills diminish the likelihood that online marketplaces implement private labels because the incentive for implementation (self-preferencing) or permission to offer private labels (a dual role) is not permitted. As a result, enacting these bills will hurt consumer welfare and economic efficiency.

Private Label Self-Preferencing Offers Economic Benefits

Self-preferencing is a standard business practice that incentivizes brick-and-mortar and online retailers to implement private label programs that encourage innovation, generate consumer welfare, and increase economic efficiency. Brick-and-mortar retailers often place their products on favorable, eye-level shelves next to comparable branded products to facilitate product comparison and encourage private-label purchases. According to Jean-Pierre Dube’s research, “Since the perceived risks from making a purchase error can reduce consumer interest in P.L.s, retailers typically position their P.L. aggressively against N.B.s. Academic research also recommends such marketing and positioning of P.L.s close to the N.B.s against which they compete.”[109]

This positioning of private labels in brick-and-mortar stores constitutes a form of self-preferencing that has generally been expected of retailers and accepted by antitrust authorities without question. However, private-label self-preferencing has recently received intense scrutiny from politicians and antitrust enforcers, who have claimed that large tech companies’ practice of private label self-preferencing is anti-competitive conduct that warrants harsh remedies. For instance, FTC Chair Khan asserted, “A second way Amazon has favored itself as a seller is through implementing Marketplace policies that enable it to become the exclusive merchant of certain products … Integration by dominant platforms gives rise to the sort of harm previously addresses through [structural] separations.”[110]

However, the prohibition of self-preferencing for online marketplaces harms innovation, consumers, and the economy.

Innovation

Critics of online marketplaces’ private label self-preferencing complain that this practice stifles innovation. They reason that online marketplaces adjust their algorithms to only recommend their brands to customers, resulting in the unlikely discovery of third-party sellers’ products and eliminating any incentives for third-party sellers to innovate. Critics seem only to consider the most extreme form of self-preferencing. Andrei Hagiu et al. described the most extreme form of self-preferencing with the following:

To model the possibility of [an online marketplace] engaging in self-preferencing, we assume that consumers rely on [the marketplace]'s recommendation to discover [a third-party seller’s] novel product, so that [the online marketplace] can steer consumers by determining whether or not they are aware of [the third party seller's] existence (e.g., through its recommendation algorithm).[111]

However, self-preferencing is not so extreme that online marketplaces altogether remove third-party sellers’ products from customer recommendations. Marketplaces may elect to place their products as the first search result and third-party products as the second or third search result; however, they seldom remove all third-party products from their platforms. Removing all third-party products is counterproductive to the platform because online marketplaces’ value stems from network effects, which is defined as “the value of a product, service, or platform depends on the number of buyers, sellers, or users who leverage it.”[112] In other words, the greater the number of sellers, the more value an online marketplace derives. Online marketplaces have every incentive to keep third-party products on their platform, thereby only practicing an acceptable form of self-preferencing that does not disincentivize innovation.

Online marketplaces’ self-preferencing instead promotes innovation by incentivizing marketplaces to innovate through imitation, which is beneficial to society and innovation.[113] According to Mingyue Hue’s research, “Imitation innovation as a way of innovation, focus on imitating creative adaptation, on the basis of technological leapfrogging, purpose is through to adapt to the new environment, meet customer demand, thus improve enterprise innovation performance, beyond the competitors.”[114]

The introduction of private-label products—whether these products are novel innovations or imitations of branded products—incentivizes online marketplaces when there is a cost advantage that can result in lower consumer prices. According to Federico Etro’s research, “Intuitively, Amazon would enter as a direct seller when its cost advantage is large relative to the advantage of sellers in marketing, generating more profits from direct sales than commissions from 3P sellers.”[115]

The removal of self-preferencing would reduce the likelihood that consumers are aware of the cheaper private label, therefore potentially generating fewer sales than from collecting commission from 3P sellers. Analogously, this prohibition is the same as prohibiting brick-and-mortar retailers from placing their private labels on an eye-level shelf, eliminating any benefits of implementing a private label in the first place. Self-referencing prohibition stifles innovation, even if that innovation is from imitation.

Consumer Welfare

Antitrust laws follow a consumer welfare standard that “directs courts to focus on the effects that challenged business practices have on consumers, rather than on alleged harms to specific competitors.”[116] Online marketplaces’ practice of self-preferencing their private labels does not violate this standard but promotes it. When self-preferencing is allowed, online marketplaces implement private labels when profits are more substantial than third-party commissions.[117] Although a marketplace’s private label entry could potentially hurt competitors due to increased competition, the implementation of private labels nevertheless benefits consumers in the form of lower prices. According to Federico Etro’s research:

The intuition is that P.L. products avoid the double marginalization created by commissions and high markups of 3P sellers, while 1P retail is less profitable when manufacturers with high market power exploit the advantage of the platform in logistics by increasing their wholesale prices … Entry has a beneficial effect on prices from the point of view of consumers.[118]

Additionally, private labels also lower prices on third-party products, which further benefits consumers. Andrei Hagiu et. al. further noted in their research “that such a ban often benefits third-party sellers at the expense of consumer surplus or total welfare. The main reason for this is that in dual mode, the presence of the platform’s products constrains the pricing of the third-party sellers on its marketplace, which benefits consumers.”[119]

There is no reason to challenge online marketplaces’ self-preferencing of private labels because it incentivizes the implementation of private labels, benefitting consumers with lower prices.

Moreover, self-preferencing resulting in private label implementation also increases product variety, enhancing overall consumer welfare. Consumers generally prefer a more extensive selection of products.[120] According to German Gutierrez’s research, “Consumers value … product variety. Intervention that eliminate … [product variety decreases] consumer as well as total welfare. By contrast, interventions that preserve … product variety but increase competition—such as increasing competition in fulfillment services—may increase welfare.”[121]

Although there are concerns that online marketplaces are using data on third-party sellers to price products and adjust product offerings—a form of self-preferencing—this practice is not new. Brick-and-mortar shops also collect “sales data to shape their product offering,” often benefitting consumers through “lower prices and an increase in the variety of products available.”[122]

Online marketplaces’ private label self-preferencing is appropriate pro-competitive behavior that benefits consumers at the expense of competitors. According to D. Bruce Hoffman and Garrett D. Shinn’s article:

Self-preferencing should generally be expected to be efficient and pro-competitive. This is because a platform is agnostic to its source of revenue. Its primary interest is in maximizing traffic on the platform to drive revenue, and it will not likely take actions that endanger this interest. Because the platform’s highest interest is in maximizing traffic, the platform’s interests are a good proxy for consumer interests and welfare.[123]

Its prohibition eliminates the incentive to implement private labels, decreasing welfare and stifling price competition.

Economic Efficiency

Self-preferencing incentivizes online marketplaces to implement private labels and play a dual role of seller and marketplace for others to sell. Prohibiting private label self-preferencing for online marketplaces can lead marketplaces to abandon their dual role and become only a seller or marketplace, resulting in consequences to economic efficiency.[124] Andrei Hagiu et al. noted in their study that “a blanket ban on the dual mode, that is, one that requires platforms to choose the same mode (either seller or marketplace) across all products, is more likely to be harmful for consumers and welfare than just banning the dual mode at the level of an individual product or a narrowly defined product category.”[125]

For instance, operating as only a seller or marketplace means consumers can no longer go to a single marketplace to find all their desired products, thereby increasing transaction costs and diminishing economic efficiency. The lack of dual-role price competition will also raise consumer prices, reducing welfare and lowering economic efficiency.

Moreover, self-preferencing is a form of vertical integration that reduces costs and boosts efficiency. Although critics assert that online marketplaces' self-preferencing puts them in an unfair position as both an “umpire and a team,” leading to conflicts of interest, it is rational for firms to give preference to their affiliates due to efficiencies.[126] According to Alessandra Tonazzi and Gabriele Caravano’s CPI Antitrust Chronicles article, “it is reasonable for an undertaking to preference (to a certain extent) its downstream services as a means to boost efficiencies, economies of scales, and recoup upstream investments. The efficiency arguments for self-preferencing are indeed similar to those that traditionally apply to vertical integration.”[127]

Self-preferencing private labels is a standard and rational practice contributing to an efficient economy.

Network Effects Addressing Self-Preferencing Antitrust Concerns

Self-preferencing is usually a reasonable business practice; however, it can also take more insidious forms that antitrust laws prohibit. Extreme forms of self-preferencing that violate antitrust laws include the following exclusionary conduct: raising rivals’ costs, foreclosure of competitors, and monopoly leveraging. However, online marketplaces do not have the incentive to partake in these practices due to network effects (e.g., consumers will not value a marketplace that sells only private-label mouthwash when they want Listerine).

The predatory conduct of raising a rival’s costs is often described as a means of forcing them to exit the market.[128] In Klor’s, Inc. v Broadway-Hale Stores, the Supreme Court asserted:

Group boycotts, or concerted refusals by traders to deal with other traders, have long been held to be in the forbidden category … “such agreements, no less than those to fix minimum prices, cripple the freedom of traders and thereby restrain their ability to sell in accordance with their own judgment.” This combination takes from Klor's its freedom to buy appliances in an open competitive market, and drives it out of business as a dealer in the defendants' products.[129]

There are concerns that online marketplaces utilize this anti-competitive practice when they only charge third-party sellers a commission fee—a form of self-preferencing—resulting in higher upstream costs for third-party sellers.[130] However, despite charging a commission fee, online marketplaces have no incentive to force these sellers to exit the market because a marketplace’s value to consumers depends on the number of sellers using the marketplace. According to Kevin Adam et. al.’s research:

[C]ompared to traditional one-sided businesses where downstream firms buy inputs from upstream sellers, a platform may have more limited incentives to raise rivals’ costs. Digital marketplaces create value by facilitating the interactions between sellers and buyers … they are typically characterized by strong indirect network effects, meaning that more or higher-quality sellers increase the attractiveness of the marketplace to buyers.[131]

Foreclosure of competitors is another antitrust concern when discussing online marketplaces’ private label self-preferencing practices. In Europe’s Google Search (Shopping) case, the European Commission argued that Google’s self-preferencing behavior resulted in the foreclosure of competing shopping sites, thereby harming consumer choice of using other shopping sites.[132] But Google did not block these other sites; it only self-preferenced its own site.

Analogously, the self-preferencing antitrust concerns in the United States are that online marketplaces' private label self-preferencing practices could potentially cause third-party competitors selling similar products on the marketplace to foreclose. However, network effects prevent the foreclosure of third-party sellers because forcing sellers to exit the market harms the value of the marketplaces for both consumers and future third-party sellers the marketplaces depend on for commission. In other words, online marketplaces practice a reasonable form of self-preferencing to maintain value.

Monopoly leveraging, described as “using a monopoly in one market to gain an advantage in another” by D. Bruce Hoffman and Garrett D. Shinn of Cleary Gottlieb, is especially concerning because the largest online marketplaces tend to hold a dominant position. Critics fear that online marketplaces will leverage their dominant position as a marketplace connecting buyers to sellers to create a monopoly in the downstream sellers’ market. In other words, they will leverage their dominant position as a marketplace to self-preference their private labels, creating a monopoly in those product markets. However, network effects once again constrain this practice from occurring. Although online marketplaces may have monopoly power as a marketplace, they will not leverage self-preferencing to create a monopoly in the downstream sellers’ market because that would reduce the number of sellers on their platform and thus their overall value as a marketplace. Self-preferencing is in line with the Supreme Court’s Verizon Communications Inc. v. Law Office of Curtis V. Trinko, LLP precedent: “The Court of Appeals also thought that respondent’s complaint might state a claim under a ‘monopoly leveraging’ theory. We disagree. To the extent the Court of Appeals dispensed with a requirement that there be a ‘dangerous probability of success’ in monopolizing a second market, it erred.[133]

These three antitrust concerns over online marketplaces’ private label self-preferencing practice all fall under the broad umbrella of exclusionary conduct, or “a firm raising the costs or reducing the revenues of competitors in order to induce the competitors to raise their prices, reduce output, or exit from the market” with a goal to achieve monopoly power.[134] However, network effects limit most extreme self-preferencing behaviors that aim to achieve monopoly power; hence, antitrust enforcers should not condemn this practice, and legislations prohibiting self-preferencing are not necessary.

Antitrust Enforcement: Exclusion of a Specifically Named Competitor

Network effects remove online marketplaces’ incentives to practice extreme forms of self-preferencing (e.g., preferencing their private labels with the intent to foreclose rivals) that result in exclusionary conduct, which is illegal under antitrust laws. However, one type of exclusionary conduct needs antitrust enforcement: exclusion of a specifically named competitor. When a specific competitor is named and targeted with self-preferencing practices, antitrust violations may arise. According to Aurelien Portuese of the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF):

When a company names a competitor and treats that competitor differently from other competitors without objective justification, the active exclusion or demotion may generate anti-competitive effects that constitute a violation of antitrust laws. Absent objective justifications such as quality standards, the active exclusion or demotion of a named competitor without similar treatment imposed to other competitors could constitute an anti-competitive practice subject to a rule of reason.[135]

Regardless of whether retailers operate a physical store or an online marketplace, self-preferencing their private label products with the sole intention of eliminating a specific competitor violates antitrust laws because their motive is to eliminate competition to achieve monopoly power. In this scenario, antitrust authorities should follow existing laws to impose consequences on a firm. However, new legislation prohibiting self-preferencing is still not necessary to address this antitrust concern.

Conclusion

Throughout history, private labels have benefited consumers, retailers, and the economy. They enhance consumer welfare and economic growth, while also spurring innovation. Despite these benefits, critics have nevertheless decried them, including today. The attempts to stifle retailers’ efficient business practices diminish the incentive to implement private labels, reducing consumer welfare.

Online marketplaces’ private label self-preferencing is not an anti-competitive practice. Network effects constrain the likelihood of self-preferencing resulting in anti-competitive exclusionary conduct. Antitrust enforcement is only necessary when a competitor is specifically named and subjected to exclusionary conduct with the intent to attain monopoly power. However, current antitrust laws already address this anti-competitive conduct; hence, the practice of private label self-preferencing does not warrant further legislation.

The over-arching principle “what is illegal offline must also be illegal online” guiding today’s digital regulations should also guide the practice of self-preferencing.[136] Practicing reasonable forms of self-preferencing is legal offline, therefore it is legal online, warranting no new legislation.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Rob Atkinson and Aurelien Portuese for their guidance on this report.

About the Author

Trelysa Long is a research assistant for antitrust policy with ITIF’s Schumpeter Project on Competition Policy. She was previously an economic policy intern with the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. She earned her bachelor’s degree in economics and political science from the University of California, Irvine.

About ITIF

The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) is an independent, nonprofit, nonpartisan research and educational institute focusing on the intersection of technological innovation and public policy. Recognized by its peers in the think tank community as the global center of excellence for science and technology policy, ITIF’s mission is to formulate and promote policy solutions that accelerate innovation and boost productivity to spur growth, opportunity, and progress. For more information, visit us at itif.org.

Endnotes

[1]. Numerator, “Private Label Trends,” webpage accessed November 21, 2022, https://www.numerator.com/private-label-trends.

[2]. Radojko Lukic, “The Effect of Private Brands on Business performance in Retail,” Economia. Seria Management 14, no. 1 (2011), 28, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/227490103_The_Effect_of_Private_Brands_on_Business_Performance_in_Retail.

[3]. Numerator, “Private Label Trends,” op. cit.

[4]. “The EU’s Digital Services Act–what you need to know,” The Stack, April 26, 2022, https://thestack.technology/eu-digital-services-act-what-you-need-to-know/.

[5]. Phillip B. Fitzell, Private Labels: Store Brands & Generic Products (Connecticut: AVI Publishing Co., 1982), 27.

[6]. Ibid., 28.

[7]. Ibid., 30

[8]. Ibid., 35

[9]. Ibid., 30–32.

[10]. Andres Cuneo et al., “The Growth of Private Label brands: A Worldwide Phenomenon,” Journal of International Marketing 23, no. 1 (2015): 74, https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/43966481.pdf.

[11]. Fitzell, Private Labels: Store Brands & Generic Products, 31.

[12]. Ibid., 40.

[13]. Eric Almquist et. al., “The Element of Value,” Harvard Business Review, September 2016, https://hbr.org/2016/09/the-elements-of-value.

[14]. Fitzell, Private Labels: Store Brands & Generic Products, 28.

[15]. James L. Hamilton and Ibrahim Mqasqas, “Double marginalization and Vertical Integration: new Lessons from Extensions of the Classic Case,” Southern Economic Journal 62, no. 3 (1996): 567, https://www.jstor.org/stable/1060880#metadata_info_tab_contents.

[16]. Phillip B. Fitzell, The Explosive Growth of Private Labels in North America: Past, Present, and Future (Global Books Production, 1998), 35.

[17]. Fitzell, Private Labels: Store Brands & Generic Products, 30.

[18]. Glossary of Industrial Organisation Economics and Competition Law, compiled by R. S. Khemani and D. M. Shapiro, commissioned by the Directorate for Financial, Fiscal and Enterprise Affairs, OECD, 1993, https://stats.oecd.org/glossary/detail.asp?ID=3177.

[19]. Fitzell, Private Labels: Store Brands & Generic Products, 28.

[20]. Jerry A. Hausman, Ariel Pakes, and Gregory L Rosston, “Valuing the Effect of Regulation on New Services in Telecommunications,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Microeconomics 1997 (1997): 2, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2534754#metadata_info_tab_contents.

[21]. Fitzell, Private Labels: Store Brands & Generic Products, 28.

[22]. Cherroun Reguia, “Product Innovation and the Competitive Advantage,” in Principles of State-Building: The Case of Kosovo (Macedonia: European Scientific Institute, ESI, 2014), 148–149.

[23]. “Barry’s Anti-Trust View,” The New York Times, March 19, 1897. https://www.proquest.com/hnpnewyorktimes/docview/95534784/CE49FCC058254EFEPQ/1?accountid=6579.

[24]. “Barry’s Anti-Trust View,” The New York Times, March 19, 1897. https://www.proquest.com/hnpnewyorktimes/docview/95534784/CE49FCC058254EFEPQ/1?accountid=6579.

[25]. “The Municipal Assembly: Important Resolutions Offered at Yesterday’s Meeting of City Council,” The New York Times, February 16, 1898.

[26]. J. A. Hill, “Taxes on Department Stores,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 15, no. 2 (1901) 299, https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/1884900.pdf.

[27]. Aurelien Portuese and Trelysa Long, “The Process of Creative Destruction, Illustrated: the US Retail Industry” (ITIF, October 2022), https://itif.org/publications/2022/10/03/the-process-of-creative-destruction-illustrated-the-us-retail-industry/.

[28]. Harper W. Boyd Jr. and Ronald E. Frank, “The Importance of Private Labels in Food Retailing,” Business Horizons 9, no. 2 (1966): 81, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/0007681366900371.

[29]. Herbert D. Smith, “The Fight for Inner Space: Brand Name and Private Label,” Vital Speeches of the Day 31, no. 16 (1965): 493, https://search-ebscohost-com.ezproxylocal.library.nova.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=buh&AN=9871242&site=ehost-live.

[30]. “National brands Continue to Gain: Growth of Self-Service Stores held Responsible for Lag in Private Label Foods,” The New York Times, March 17, 1950, https://www.proquest.com/hnpnewyorktimes/docview/111473216/B4E5E51ACD648AFPQ/13?accountid=6579; Fitzell, The Explosive Growth of Private Labels in North America: Past, Present, and Future, 29, 73.

[31]. Fitzell, The Explosive Growth of Private Labels in North America: Past, Present, and Future, 36–37, 69.

[32]. United States National Commission on Food Marketing, Special Studies in Food Marketing: Private Label Products in Food Retailing; Retail Food Prices in Low and Higher Income Areas; Notes on Economic Regulation (United States, U.S. National Commission on Food Marketing, 1966), https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=yLdKAQAAMAAJ&rdid=book-yLdKAQAAMAAJ&rdot=1.

[33]. Ibid.

[34]. Mary Ellen Shoup, “Inflation is Pushing Consumers Towards Private Label, Says Catalina,” Food Navigator USA, July 22, 2022, https://www.foodnavigator-usa.com/Article/2022/07/22/inflation-is-pushing-consumers-towards-private-label-says-catalina.

[35]. Gene Smith, “RCA Plans to Produce Penney’s Private Brand,” The New York Times, June 12, 1973, https://www.proquest.com/hnpnewyorktimes/docview/119873698/AB0E962C2E104739PQ/1?accountid=6579.

[36]. Isadore Barmash, “The New Brand Game is Private Labels: inflation Aids Those of Little Renown,” The New York Times, April 14, 1974, https://www.proquest.com/hnpnewyorktimes/docview/120087621/B4E5E51ACD648AFPQ/2?accountid=6579.

[37]. Leonard Sloane, “Jewelers Assess Battle of Brands: Debaters Say National and Private Labels Are Vital,” The New York Times, August 18, 1964, https://www.proquest.com/hnpnewyorktimes/docview/115912321/464944CD5E344BCPQ/7?accountid=6579.

[38]. United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, “Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Co. v. Cream of Wheat Co., 227 F. 46 91915),” Caselaw Access Project, https://cite.case.law/f/227/46/.

[39]. Fitzell, The Explosive Growth of Private Labels in North America: Past, Present, and Future, 59, 73.

[40]. Ibid., 69.

[41]. Ibid., 37.

[42]. Harper W. Boyd Jr. and Ronald E. Frank, “The Importance of Private Labels in Food Retailing,” Business Horizons 9, no. 2 (1966): 81, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/0007681366900371; Fitzell, The Explosive Growth of Private Labels in North America: Past, Present, and Future, 71.

[43]. David L. Call, “Private Label and Consumer Choice in the Food Industry,” Journal of Consumer Affairs 1, no. 2 (1967): 151, https://web-p-ebscohost-com.ezproxylocal.library.nova.edu/ehost/detail/detail?vid=5&sid=d4f34e2e-7c61-4f1f-b4ce-5c6028f78ff6%40redis&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#AN=5098120&db=buh.

[44]. Ibid.

[45]. Fitzell, The Explosive Growth of Private Labels in North America: Past, Present, and Future, 131.

[46]. Ibid., 133.

[47]. Barbara Davis Coe, “Private Versus National Preference Among Lower- and Middle-Income Consumers,” Journal of Retailing 47, no. 3 (1971): 61–72, https://search-ebscohost-com.ezproxylocal.library.nova.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=buh&AN=4673386&site=ehost-live.

[48]. Fitzell, The Explosive Growth of Private Labels in North America: Past, Present, and Future, 29, 69.

[49]. Call, “Private Label and Consumer Choice in the Food Industry,” 155.

[50]. Ibid.

[51]. Fitzell, The Explosive Growth of Private Labels in North America: Past, Present, and Future, 30, 91–92.

[52]. Call, “Private Label and Consumer Choice in the Food Industry,” 155.

[53]. Fitzell, The Explosive Growth of Private Labels in North America: Past, Present, and Future, 134.

[54]. Anne ter Braak and Barbara Deleersnyder, “Innovation Cloning: The Introduction and Performance of Private Label Innovation Copycats,” Journal of Retailing 94, no 3 (2018): 312, https://www.proquest.com/citedreferences/MSTAR_2108831812/F53C14B5E8474C0DPQ/1?accountid=6579.

[55]. Call, “Private Label and Consumer Choice in the Food Industry,” 160.

[56]. Reguia, “Product Innovation and the Competitive Advantage,” 148–149.

[57]. Fitzell, The Explosive Growth of Private Labels in North America: Past, Present, and Future, 96.

[58]. Paul Ingram and Hayagreeva Rao, “Store Wars: The Enactment and repeal of Anti-Chain Store Legislation in America,” American Journal of Sociology 110, no. 2 (2004): 450, http://www.columbia.edu/~pi17/ingram_rao.pdf.

[59]. Barry C. Lynn, “Breaking the chain: The antitrust case against Wal-Mart,” Harper Magazine, 2006, https://harpers.org/archive/2006/07/breaking-the-chain/.

[60]. Donald S. Clark, “The Robinson-Patman Act: Annual Update,” public statement, April 2, 1998, https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/speeches/robinson-patman-act-annual-update.

[61]. Arthur Medow, “Difference in Cost and brand Valuation as Justification for Private Label Prices,” Antitrust Law Journal 39, no. 4 (1970): 858, https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/40841869.pdf.

[62]. William L. Jaeger, “Antitrust: Dual Distribution by Brand and a Test of Like Grade and Quality Under the Robinson-Patman Act,” California Law Review 55, no. 2 (1967): 535-536, https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/3479360.pdf; The Borden Company, Petitioner, v. Federal Trade Commission, Respondent, 381 F.2d 175 (5th Cir. 1967), https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/appellate-courts/F2/381/175/55641/.

[63]. Ibid.

[64]. The Borden Company, Petitioner, v. Federal Trade Commission, Respondent, 381 F.2d 175 (5th Cir. 1967), https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/appellate-courts/F2/381/175/55641/ (where the Fifth Circuit notes, “We are of the firm view that where a price differential between a premium and nonpremium brand reflects no more than a consumer preference for the premium brand, the price difference creates no competitive advantage to the recipient of the cheaper private brand product on which injury could be predicated.”); Jaeger, “Antitrust: Dual Distribution by Brand and a Test of Like Grade and Quality Under the Robinson-Patman Act,” 535–536.

[65]. Ryan Luchs et. al., “The End of the Robinson-Patman Act? Evidence from Legal Case Data,” Management Science 56, no. 12 (2010): 2124, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40959625#metadata_info_tab_contents.

[66]. Ibid.

[67]. Zachary Russell, “Inflation Continues to Grow Private Label, Per Study,” Store Brands, March 8, 2022, https://storebrands.com/inflation-continues-grow-private-label-study.

[68]. John Quelch and David Harding, “Brands Versus Private Labels: Fighting to Win,” Harvard Business Review, January-February 1996, https://hbr.org/1996/01/brands-versus-private-labels-fighting-to-win.

[69]. T. Ozbun, “U.S. Private Label Market - Statistics & Facts,” Statista, August 19. 2022, https://www.statista.com/topics/1076/private-label-market/#dossierKeyfigures.

[70]. John Quelch and David Harding, “Brands Versus Private Labels: Fighting to Win,” Harvard Business Review, January–February 1996, https://hbr.org/1996/01/brands-versus-private-labels-fighting-to-win.

[71]. Russell, “Inflation Continues to Grow Private Label, Per Study.”

[72]. Maria Monteros, “Target Shaped Private Labels Into Powerhouse Brands. Now Other Want to Do the Same,” Retail Dive, November 10, 2021, https://www.retaildive.com/news/target-shaped-private-labels-into-powerhouse-brands-now-others-want-to-do/609762/; Tonya Garcia, “Walmart Launches Private-Label Clothing Brand Free Assembly,” Market Watch, September 21, 2020, https://www.marketwatch.com/story/walmart-launches-private-label-clothing-brand-free-assembly-11600707760.

[73]. Julie Creswell, “How Amazon Steers Shoppers to Its Own Products,” The New York Times, June 23, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/23/business/amazon-the-brand-buster.html; Hearing of the Subcommittee on Antitrust, Commercial, and Administrative law and Committee on the Judiciary, “Responses to Questions for the Record Following the July 16, 2019, Hearing of the Subcommittee on Antitrust, Commercial, and Administrative Law, Committee on the Judiciary, Entitled "Online Platforms and Market Power, Part 2: Innovation and Entrepreneurship” (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Congress, October 2019), https://www.ecomcrew.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/HHRG-116-JU05-20190716-SD038.pdf; Amazon, “Amazon.com Introduces AmazonBasics,” press release, September 19, 2009, https://press.aboutamazon.com/news-releases/news-release-details/amazoncom-introduces-amazonbasics.

[74]. Greg Bensinger, "Amazon to Expand Private-Label Offering—From Food to Diapers; The First of the Brands Could Appear on the Company's Website in Coming Weeks," The Wall Street Journal, May 15, 2016, https://www.wsj.com/articles/amazon-to-expand-private-label-offeringsfrom-food-to-diapers-1463346316.

[75]. Fitzell, The Explosive Growth of Private Labels in North America: Past, Present, and Future, 31.

[76]. Ibid.

[77]. “More Consumers Choosing Private Label, Says Nielsen,” Progressive Grocer, November 18, 2008, https://progressivegrocer.com/more-consumers-choosing-private-label-says-nielsen.

[78]. Bensinger, “Amazon to Expand Private-Label Offering—From Food to Diapers; The First of the Brands Could Appear on the Company’s Website in Coming Weeks.”.

[79]. “The Effect of Private Brands on Business performance in Retail,” 28.

[80]. “The Rise and Rise Again of Private Label” (industry report, The Nielsen Company, 2018), https://www.nielsen.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2019/04/global-private-label-report.pdf.

[81]. Jin Young Park, Kyungdo Park, and Alan J. Dubinsky, “Impact of Retailer Image on Private brand Attitude: Halo Effect and Summary Construct,” Australian Journal of Psychology 63, no. 3 (2011): 173, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/j.1742-9536.2011.00015.x.

[82]. Colleen Collins-Dodd and Tara Lindley, “Store Brands and Retail Differentiation: The Influence of Store Image and Store brand Attitude on Store Own Brand Perception,” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 10, no. 6 (2003): 350-351, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0969698902000541?via%3Dihub.

[83]. Ibid.

[84]. Park, Park, and Dubinsky, “Impact of Retailer Image on Private brand Attitude: Halo Effect and Summary Construct,” 173.

[85]. “PLMA’s 2022 Private Label Report” (industry report, Private Label Manufacturers Association, 2022), https://plma.com/sites/default/files/files/2022-02/feb-16annualreport01.pdf.

[86]. Ibid.

[87]. Lukic, “The Effect of Private Brands on Business performance in Retail,” 28,.

[88]. Shailendra Singh Bisht and Jitesh Nair, “Kirkland Signature Private Label Powering Costco,” IUP Journal of Marketing Management 20, no. 4 (2021): 353, https://search-ebscohost-com.ezproxylocal.library.nova.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=buh&AN=154745301&site=ehost-live.

[89]. Ibid.

[90]. Robert L. Steiner, “The Nature and Benefits of National Brand/Private Label Competition.” Review of Industrial Organization 24, no. 2 (2004): 114, https://doi.org/10.1023/b:reio.0000033351.66025.05.

[91]. Giulia Tiboldo et al., “Competitive and Welfare Effects of Private Label Present in Differentiated Food Markets,” Applied Economics 54, no. 24 (2021): 2715, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00036846.2020.1866160.

[92]. “Private Brands 2021: Consumer Demand for Private Brands” (industry report, IRI, December 2021), https://www.iriworldwide.com/IRI/media/Library/Consumer-Demand-for-Private-Brands-Dec-2021.pdf.

[93]. Singh Bisht and Nair, “Kirkland Signature Private Label Powering Costco.”. ../../../../../Users/TrelysaLong/Dropbox (ITIF)/PC/Desktop/ITIF-Trelysa/Private Labels August/Section 3 Sources/kirkland powering costco.pdf

[94]. Reguia, “Product Innovation and the Competitive Advantage,” 148–149.

[95]. Ibid.

[96]. Joseph A. Schumpeter, Socialism, Capitalism, and Democracy (Dancing Unicorn Books, 2016), 169.

[97]. Nina Veflen Olsen et al., “Consumer Liking of Private Labels. An Evaluation of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Orange Juice Cues,” Appetite 56, no. 3 (2011): 775–776 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0195666311001085.

[98]. Giulia Tiboldo et al., “Competitive and Welfare Effects of Private Label Present in Differentiated Food Markets,” 2722.

[99]. Ibid, 2714, 2722.

[100]. Ibid.

[101]. Katherine Van Dyck, “Price Discrimination and Power Buyers: Why Giant Retailers Dominate the Economy and How to Stop It” (American Economic Liberties Project, September 2022), https://www.economicliberties.us/our-work/price-discrimination-and-power-buyers-why-giant-retailers-dominate-the-economy-and-how-to-stop-it/.

[102]. Lina M. Khan, “The Separation of Platforms and Commerce,” Columbia Law Review 199, no. 4 (2019), https://columbialawreview.org/content/the-separation-of-platforms-and-commerce/.

[103]. White House, Executive Order on Promoting Competition in the American Economy.

[104]. Ibid.

[105]. Jerrold Nadler and David N Cicilline, Investigation of Competition in Digital Markets (Washington, D.C.: House of Representatives, July 2022), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CPRT-117HPRT47832/pdf/CPRT-117HPRT47832.pdf.

[106]. American Innovation and Choice Online Act, S. 2992, 117th Cong. (2021–2022), https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/senate-bill/2992/text; Ending Platform Monopolies Act, H.R. 3825, 117th Cong. 2021–2022), https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/3825/text.

[107]. Aurelien Portuese, “Is Congress Committed to Making American Consumers’ Lives Costlier?” Washington Legal Foundation, January 12, 2022, https://www.wlf.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/011122Portuese_LP.pdf.

[108]. Pramila Jayapal, “Jayapal and Lawmakers Release Anti-Monopoly Agenda for 'A Stronger Online Economy: Opportunity, Innovation, Choice,'” news release, June 11, 2021, https://jayapal.house.gov/2021/06/11/antitrust-legislation/.

[109]. Jean-Pierre H. Dube, “Amazon Private Brands: Self-Preferencing vs Traditional Retailing,” SSRN, (2022): 8, https://ssrn.com/abstract=4205988 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4205988.

[110]. Khan, “The Separation of Platforms and Commerce.”

[111]. Andrei Hagiu, Tat-How Teh, and Julian Wright, “Should platforms be allowed to sell on their own marketplaces?” The Rand Journal of Economics 53, no. 2 (2022), https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1756-2171.12408.

[112]. Tim Stobierski, “What Are Network Effects?” Harvard Business Review, November 12, 2020, https://online.hbs.edu/blog/post/what-are-network-effects.

[113]. Mingyue Hu, “Literature Review on Imitation Innovation Strategy,” American Journal of Industrial and Business Management 8, no. 8 (2018), https://file.scirp.org/Html/3-2121275_86751.htm.

[114]. Ibid.

[115]. Federico Etro, “Product selection in online marketplaces,” Journal of Economics & Management Strategy 30, no. 3 (2021), https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/jems.12428.

[116]. Samuel Bowman, “TL;DR- Consumer Welfare Standard,” International Center for Law and Economics, February 9, 2021, https://laweconcenter.org/resource/tldr-consumer-welfare-standard/.

[117]. Etro, “Product selection in online marketplaces.”

[118]. Ibid.

[119]. Andrei Hagiu, Tat-How Teh, and Julian Wright, “Should platforms be allowed to sell on their own marketplaces?”

[120]. German Gutierrez, “The Welfare Consequences of Regulating Amazon,” (2022), http://germangutierrezg.com/Gutierrez2021_AMZ_welfare.pdf.

[121]. Ibid.

[122]. Kevin C. Adam, Juliette Caminade, and Christopher R. Knittel, “The Intersection of Self-Preferencing and pricing practices in the Digital World,” American Bar Association June 2022 (2022): 6, https://www.analysisgroup.com/globalassets/insights/publishing/2022-price-point-june-2022-monthly-highlight-newsletter.pdf.

[123]. D. Bruce Hoffman and Garrett D Shinn, “Self-Preferencing and Antitrust: Harmful Solutions for an Improbable Problem,” CPI Antitrust Chronicle June 2021 (2021): 7, https://www.clearygottlieb.com/-/media/files/cpi--hoffman--final-pdf.pdf.

[124]. Andrei Hagiu, Tat-How Teh, and Julian Wright, “Should platforms be allowed to sell on their own marketplaces?”

[125]. Ibid.