With Customer Satisfaction at a New Low, Federal Agencies Still Fail to Measure It Well or Provide Enough Digital Services

The Biden administration has made improving customer experience (CX) a top priority for federal agencies. That hinges on providing robust digital services. But agencies are behind in digital adoption, and they don’t do enough to measure CX via digital platforms, much less to improve.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Key Takeaways

Contents

The Federal Government’s Continued Focus on Customer Experience 3

What Does Customer Experience Mean in the Federal Government? 3

What Are Federal High-Impact Service Providers? 4

Why Is Customer Experience an Important Focus Area for Federal Services? 4

Why Are Digital Services Important for Customer Experience in the Federal Government? 6

HISP Efforts to Measure Customer Experience 8

Level of Digital Services at HISPs 10

Introduction

The U.S. federal government is enormous. Hundreds of agencies with millions of employees spend trillions of dollars annually, often acting as the sole-source service provider to a diverse customer base with varying needs. Within this sprawling bureaucracy, federal HISPs oversee large, critical programs such as Medicare, Social Security, and small business loans. And yet, according to multiple recent studies, customer satisfaction with the federal government—which has never had a strong reputation for customer service—has steadily declined to historic lows.[1]

In response, the Biden administration, like other administrations before it, has crafted a management agenda for federal agencies that designates improving customer experience as a key priority across government. When customers can do practically everything from their laptops or smartphones, digital technology disproportionally contributes to greater customer satisfaction in service delivery—especially following a pandemic that saw digital transformation accelerate across all industries. This customer preference for digital technology is likely one reason why the Biden administration’s guidance and other legislation emphasize digital services in support of improved customer experience. Despite this guidance, however, the level of adoption of digital services in HISPs is still too low. If federal agencies hope to make a meaningful impact in improving customer experience, they need to increase digital adoption more quickly, and that will require making these service as easy to use as going to a major online retailer and ordering an item. This report recommends enhancing oversight and addressing HISPs’ non-compliance with existing requirements for digital experiences that focus on modernizing websites and expanding mobile friendliness, improving how federal agencies use data to drive continuous improvements to digital services based on customer feedback, and giving HISPs the financial and regulatory clearance that catalyzes digital transformation. Otherwise, these executive priorities and laws are lip service to federal customers who will continue to find interacting with the government underwhelming, convoluted, and frustrating.

The Federal Government’s Continued Focus on Customer Experience

Due to historic lows in customer satisfaction, recent presidential administrations and Congress have made improving customer experience—particularly through advancing digital technologies—a foundational priority for federal service providers.

What Does Customer Experience Mean in the Federal Government?

OMB—the federal agency that oversees presidential management priorities across the executive branch—defines federal customers as “any individual, business, or organization (such as a grantee or State, local, or Tribal entity) that interacts with an agency or program, either directly or through a federally-funded program administered by a contractor, nonprofit, or other Federal entity.”[2] The federal government is one of the largest organizations and employers in the world, providing a wide variety of services—from Medicare and Green Cards to farm loans and duck stamps—to a large, diverse, and recurring customer base.[3]

Who Are Federal Customers?

§ 88.3 million Americans with low income or limited resources enrolled in Medicaid[4]

§ 261 million individuals and businesses that file tax returns each year[5]

§ 64 million Americans over the age of 65 enrolled in Medicare[6]

§ 4 million businesses that received COVID economic injury disaster loans[7]

§ Half of the 20 million veterans receiving government benefits[8]

§ And many more

OMB describes customer experience both transactionally (“a combination of factors that result from touchpoints between an individual, business, or organization and the Federal Government over the duration of an interaction and relationship”) and experientially (“the public’s perceptions of and overall satisfaction with interactions with an agency, product, or service”).[9] Additionally, the Biden administration includes equity and accessibility in customer experience.[10] Taken as a whole, customer experience with the federal government involves one-off, cumulative, and recurring interactions between hundreds of federal departments and individual people, organizations, or businesses of different backgrounds and needs that result in degrees of customer satisfaction regarding the service received.[11]

What Are Federal High-Impact Service Providers?

Federal HISPs are “those Federal entities designated by OMB that provide (or fund) high impact customer-facing services, either due to a large customer base or a high impact on those served by the program.”[12] Current HISPs include 35 service providers across 17 federal agencies.[13]

Figure 1: OMB-designated federal high-impact service providers (HISPs)

HISPs are primarily civilian agencies, such as the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS), Social Security Administration (SSA), Internal Revenue Service (IRS), and Food and Nutrition Service (FNS), that oversee large programs and services millions of federal customers rely on, such as Medicare, Medicaid, food assistance, and supplemental income. These programs and services are “high touch” regarding their day-to-day interactions with federal customers. In the first quarter of FY 2022, for example, HISPs reported over 370 million service interactions with the American public.[14]

Why Is Customer Experience an Important Focus Area for Federal Services?

Federal agencies are the sole-source service providers for many services, such as filing taxes, renewing a passport, and applying for a visa. Due to law or circumstance, customers who want these services have no choice but to interact with the federal government. Given the critical nature of many federal services and the sheer number of customers, it’s understandable—necessary, in fact—that quality customer experience is central to federal agencies’ operations. And yet, there have been historical challenges with customer satisfaction in the federal government.

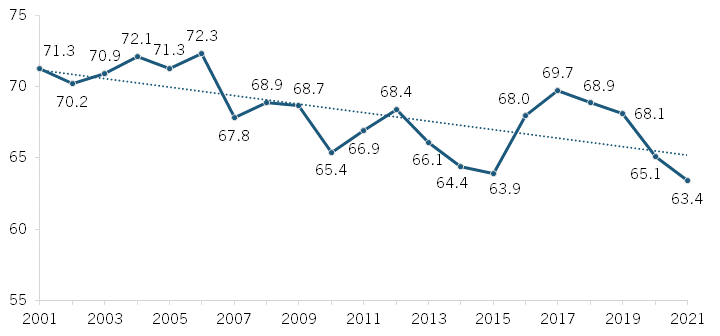

The 2021 report from the American Customer Satisfaction Index (ACSI)—a national indicator of the quality of economic output for goods and services as experienced by consumers of that output—finds that citizen satisfaction with federal government services dropped to an all-time low after steady declines over the past five years.[15]

Figure 2: Citizen satisfaction with federal government services, 2001–2021 (index scores, 0–100)[16]

Similarly, Forrester’s U.S. 2022 Customer Experience Index ranks the federal government last in customer experience among 13 industries, with most federal customers reporting their experience as “poor” or “very poor.”[17]

Given these findings, it’s not surprising that both the Trump and Biden administrations sought to reverse trends in customer dissatisfaction with the federal government. Both administrations updated and expanded OMB Circular A-11 Section 280, “Managing Customer Experience and Improving Service Delivery.” [18] These guidelines aim to “establish a more consistent, comprehensive, robust, and deliberate approach to CX across government” and subject HISPs to tracking and reporting on improvements in customer satisfaction in their agency. [19]

Furthermore, the November 2021 Biden-Harris President’s Management Agenda (PMA)—an executive roadmap for management priorities across federal agencies—includes customer experience as one of three priorities.[20] Like OMB Circular A-11 Section 280, the PMA focuses on improving customer experience across HISPs in the short term and specifies a shift to customer-designated, cross-agency life experiences in the long term. Other strategies of the PMA CX priority emphasize HISPs reporting on customer experience and recruiting staff with expertise in user testing, service design, and human-centered design.

Finally, the Biden administration issued a December 2021 executive order (EO) “Transforming Federal Customer Experience and Service Delivery to Rebuild Trust in Government” that directs federal agencies to “put people at the center of everything the Government does.”[21] Though the EO doesn’t specify timelines, it does outline actions HISPs are expected to take to improve customer experience for specific services.

Notably, OMB Circular A-11 Section 280, PMA, and CX EO emphasize the role of digital services in enhancing overall customer experience.

Why Are Digital Services Important for Customer Experience in the Federal Government?

Research findings over the past decade have confirmed customer preference in accessing government services through digital channels, such as websites, smartphones, or public-access computer kiosks, over traditional service channels, such as in-person office visits, telephone calls, or mail. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic—which further accelerated digital-first interactions across practically all industries—customers used their phones and desktops to manage their money, order groceries, and schedule dental appointments.[22] Customers have come to expect digital experiences with businesses in their day-to-day lives and have extended that expectation to government.

Digital services make more distant (federal) government feel closer, offering more accessible interactions and thus improving customer satisfaction.

Customer preference for digital services isn’t new or revelatory information. A Pew Research Center survey in 2010 found that “fully 82% of internet users (representing 61% of all American adults) looked for information or completed a transaction on a government website,” and another Pew study from 2015 found that two-thirds of Americans use the Internet to connect with government.[23] These preferences have held steady. More recently, in 2019, a Brookings survey found that 51 percent of Americans prefer digital access to government services over phone calls or personal visits to agency offices.[24] As demonstrated in the previous section, customer satisfaction in government has been low and declining for some time, and it is likely the preference for digital channels would be even higher if government services were better. In fact, a 2021 report from Deloitte Insights finds that “a citizen’s digital experience with a government agency was a strong predictor of their overall level of trust” and that state and local agencies’ stronger emphasis on digital services is part of the reason they experience relatively higher levels of customer satisfaction.[25] Customers generally favor closer (local) governments. Digital services make more distant (federal) government feel closer, offering more accessible interactions and thus improving customer satisfaction.

Customer demand for digital is further reflected by the fact that 19 of the 35 HISP websites are among the top 100 most visited according to the Digital Analytics Program (DAP), which collects web traffic from 400 executive branch government domains across 5,700 total websites.[26]

Table 1: Most-visited federal HISP websites (August 2022)

|

Department |

HISP |

Website |

Monthly Visits |

Federal Ranking |

|

Treasury |

Internal Revenue Service |

irs.gov |

37,485,512 |

10 |

|

Social Security Administration |

Social Security Administration |

ssa.gov |

24,823,279 |

11 |

|

Education |

Federal Student Aid |

studentaid.gov |

21,363,476 |

13 |

|

State |

Passport Services |

travel.state.gov |

19,568,905 |

16 |

|

Interior |

National Park Service |

nps.gov |

18,325,639 |

17 |

|

Homeland Security |

Citizen and Immigration Services |

uscis.gov |

16,458,316 |

19 |

|

Health and Human Services |

Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services |

medicare.gov |

7,692,403 |

25 |

|

Veterans Affairs |

Veterans Health Administration |

myhealth.va.gov |

6,950,324 |

29 |

|

Homeland Security |

Transportation Security Administration |

tsa.gov |

6,222,795 |

33 |

|

Homeland Security |

Customs and Border Protection |

esta.cbp.dhs.gov |

5,860,648 |

34 |

In response to preference and increased demand for digital services over the past few decades, Congress and presidential administrations have passed laws and issued guidance to improve customer-facing digital services. These include:

▪ E-Government Act, or E-Gov Act, of 2002: Established the role of the Federal Chief Information Officer (CIO) within OMB and specified a framework for federal agencies to use “Internet-based information technology to enhance citizen access to Government information and services.”[27]

▪ Executive Order 13571, Streamlining Service Delivery and Improving Customer Service (April 27, 2011): Emphasized the use of “the Internet or mobile phone” and “innovative technologies to accomplish … customer service activities.”[28]

▪ Digital Government Strategy of 2012: Sought to implement a strategic plan around the federal government’s use of digital technology, with objectives focusing on access via multiple platforms, secure shared services, and data. While the strategy includes a directive for the General Service Administration (GSA) to “identify tools and guidance for measuring performance and customer satisfaction on digital services,” the strategy itself doesn’t specify metrics or outcomes—measuring the impact of digital services on customer experience continues to be an issue today.[29]

▪ GSA IT Modernization Center of Excellence (COE) for Customer Experience (2017): The Trump administration established COEs within GSA to accelerate “IT modernization across the government to improve the public experience and increase operational efficiency,” with the CX COE explicitly focusing on customer needs.[30]

▪ 21st Century Integrated Digital Experience Act, or 21st Century IDEA, of 2018: Focuses on improving government customers’ digital experience when accessing public-facing federal websites.[31]

21st Century IDEA is the latest substantive legislation reflecting the federal government’s continued awareness that digital services are pivotal to improving customer experience. The law requires all executive branch agencies to modernize their websites, digitize services and forms—including accelerating adoption of e-signatures—and transition to centralized shared services, including complying with standards from the U.S. Web Design System (USWDS), the federal government’s resource to build accessible, mobile-friendly websites.[32] 21st Century IDEA also tasks agency CIOs with aligning digital experiences with programs and strategies of the agency overall.[33]

In addition, 21st Century IDEA clearly informs recent updates and guidance in OMB Circular A-11 Section 280 related to the priority of digital experiences over traditional channels: “Agencies should ensure, to the greatest extent practicable, that all services are made available through a digital channel using customer experience industry best practices and human centered design.”[34]

In fact, both the Biden-Harris PMA and CX executive orders emphasize leveraging digital channels to improve overall customer experience. Like 21st Century IDEA, one of the PMA’s strategies includes prioritizing the adoption of shared services and “modular, common building blocks for digital services.”[35] Of the 67 designated services in the PMA that HISPs are expected to improve, 29 are explicitly for digital services. Similarly, 17 of the 36 improvement “commitments” included in the CX EO target digital services, and nearly all are directed at HISPs. Finally, the Federal CIO shared an IT Operating Plan in June 2022 that includes “Digital-First Customer Experience” as a key priority when using money from dedicated information technology (IT) funding channels.

Summary

Historically, customer satisfaction with the federal government has fallen short. In response, recent legislation and executive guidance, such as 21st Century IDEA, OMB Circular A-11 Section 280, the Biden-Harris PMA, and CX EO, have sought to improve overall customer experience across the board, particularly for designated services provided by HISPs. Because recent findings demonstrate that robust digital services enhance customer experience overall, federal policies and guidance explicitly emphasize the use of digital technology in federal service delivery.

And yet, even after more than 20 years of congressional and administration efforts, the federal government continues to struggle in measuring customer satisfaction with and growing digital services to improve customer experience overall, particularly compared with leading-edge private sector companies.

HISP Efforts to Measure Customer Experience

The PMA references the poor ranking of the federal government in Forrester’s Customer Experience Index and aspires for the federal customer experience to be on par with the private sector.[36] As such, reporting on HISP customer experience is a central component of the Biden-Harris PMA.

Findings

To measure progress toward improved customer experience, HISPs must report customer experience data and planning activities to OMB through three mechanisms. The first is quarterly customer feedback data collected via phone, email, and online surveys across seven categories: satisfaction, confidence/trust, quality, ease/simplicity, efficiency/speed, equity/transparency, and employee helpfulness. HISPs are also required to provide annual “CX Action Plans” and “CX Capacity Assessments,” which aim to keep OMB informed regarding HISPs’ various activities and projects focused on improving customer experience, as well as share any barriers or challenges the HISPs may be facing in these efforts.

Based on the most recent data from Q2 of FY 2022 available on the “Customer Feedback on Federal Service Performance” dashboard available at performance.gov/cx, 23 of 35 HISPs are currently collecting customer feedback (with the 10 newest HISPs to begin reporting by FY 2023 Q1). These HISPs received over 1.3 million responses from federal customers during this period. Nearly all seven indicators measuring customer experience fell from the previous quarter. Overall satisfaction across reporting HISPs was down to 4.15 out of 5, with confidence/trust also going down to 3.83.[37]

These results aren’t necessarily bad—and more quarter-to-quarter data over time will be needed to better understand what’s happening—but close to half of these responses came from telephone interactions. Many HISPs have struggled to answer phone calls from customers—for example, only 11 percent of citizens that tried calling the IRS in FY 2021 reached a customer service representative—which leaves a sizable portion of federal customers who are likely dissatisfied but do not end up completing a survey over the phone.[38] This measurement gap could be substantial and, given that 43 percent of customer data is collected by phone, calls into question the accuracy of reported customer satisfaction. The equity/transparency score also conflicts with results from Forrester’s 2021 Customer Experience Index, which finds customer experience to vary widely by demographic group and generally concludes “the quality of HISPs’ customer feedback collection efforts [to be] weak, which throws into doubt the accuracy and usefulness of their data.”[39]

Many HISPs have struggled to answer phone calls from customers, which leaves a sizable portion of federal customers who are likely dissatisfied but do not end up completing a survey over the phone.

For FY 2021 CX Action Plans and Capacity Assessments, HISPs self-reported using an OMB-provided template that asks agencies to reflect on and summarize their relevant customer experience activities, including sharing pandemic-related initiatives, an equity assessment, and specific customer experience commitments. Of the 35 HISPs, 13 did not have publicly available action plans and assessments on the performance.gov/cx website. The template does not directly ask HISPs to report on how digital services are being used to enhance customer experience. However, 19 of the 22 available plans included initiatives focusing on digital services. (The in-progress FY 2022 CX Action Plan template does ask HISPs to share information around digital services through two high-level questions: “How are you leveraging digital products or self-service tools?” and “How are you leveraging technology and digital improvements?”[40]) Also worth noting is 18 plans expressed a need to improve the gathering and analyzing of customer data.[41]

Despite digital technologies playing an outsized role in the administration’s directives to HISPs on improving service delivery, PMA reporting doesn’t require HISPs to track progress or customer feedback with digital services, such as measuring customer satisfaction through surveys following the completion of a task on the HISP website or after making an update to their account through a mobile device. The lack of measurement in customer satisfaction with HISP digital services is a critical missing element with the PMA CX reporting. Of the HISPs reporting for FY 2021, only 12 captured feedback through digital channels (i.e., websites), and only 5 of these appeared to use surveys on mobile devices. HISPs collected nearly 70 percent of customer feedback data from phone and email surveys rather than through integrated digital interactions. Though the data is not comprehensive, customer satisfaction with digital services is even lower (4.0 out of 5) compared with overall satisfaction (4.15).[42]

Conclusions

HISPs are not doing enough to measure customer experience with digital services.

Despite most customers using computers or phones to interact with government, as well as digital services being a focal point in both the Biden-Harris PMA and CX EO, HISPs are not capturing enough feedback via website or mobile interactions to properly understand—and thus continuously improve—customer experience with digital products. This inaction directly goes against legislation and guidance to agencies. The CX EO tasks HISPs with capturing “observations of customer interaction with the agency’s website or application processes and tools.”[43] Per 21st Century IDEA, Agency CIOs are expected to “[use] qualitative and quantitative data … relating to the experience and satisfaction of customers, identify areas of concern that need improvement and improve the delivery of customer service.”[44] The need to expand on customer data collection and user research is a common theme across HISP CX Assessments, yet most—if not all—do not specify clear plans for accomplishing these activities with their digital services.[45]

Customer satisfaction across HISPs has been declining and is low compared with the private sector.

Based on customer data collected and reported by HISPs, customer satisfaction with HISP services has been declining, and customer experience with digital services appears to be even worse (though, as the previous conclusion illustrates, there’s not enough data here). Other findings and reports rank customer experience with the federal government lower than that of the private sector, and customer satisfaction with the federal government has reached historic lows.

Level of Digital Services at HISPs

In looking at HISP digital services based on 21st Century IDEA requirements—namely the state of website modernization and standardization, mobile-friendliness and accessibility of digital channels, and use of shared services—the level of adoption of digital services is too low.

Findings

Outside the limited PMA CX data and qualitative reporting for digital services, there is evidence that adoption of public-facing digital services based on 21st Century IDEA requirements and executive guidance is too low across HISPs. Key figures include:

▪ Only about one-third of HISPs have USWDS-powered sites, resulting in websites with widely varying styles, layouts, and features.[46]

▪ Only nine federal agencies (and no HISPs) have used Federalist, United States Digital Service’s (USDS’s) publishing platform for websites that align with 21st Century IDEA requirements.[47]

▪ Search.gov—a standardized, shared-service search engine built by the government for federal websites—only supports around half of HISP websites (and 35 percent of all federal domains).[48]

▪ Only a small portion of HISP websites and applications use login.gov, a single sign-on service across multiple federal websites that supports enhanced identity and access management.[49]

▪ While nearly all HISP websites are at least mobile responsive, two websites are still not “configured in such a way that the website may be navigated, viewed, and accessed on a smartphone, tablet computer, or similar mobile device.”[50]

▪ There are only ten native mobile apps across all HISPs with average app store ratings of 4.1 (Google Play) and 3.8 (Apple App Store) out of 5, compared with around 4.5 for popular commercial apps.

▪ An Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) report from 2021 finds that nearly half of the most popular federal websites did not pass an automated accessibility test on at least one of their three most popular pages, including 7 of the 14 HISP websites tested.[51]

“Behind-the-scenes” enterprise IT systems can also impact customer experience, particularly when they slow processing time. In 2019, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) released a report listing the top 10 most expensive legacy systems ranging in age from 8 to 51 years old that cost around $340 million each year to maintain and are less effective in supporting service delivery.[52] Of these ten legacy systems, six belong to HISPs, including a Department of Education system that processes federal student aid applications and an IRS system that manages taxpayer data.[53] Similarly, cloud computing allows federal agencies to extend their digital capabilities and offers greater security to support customer trust. Still, cloud adoption in the federal government is much slower than in the private sector.[54]

Conclusions

The low level of adoption of HISP digital services that support enhanced customer experience is low due to regulatory and operational barriers and HISPs not fully utilizing available resources.

As mentioned in previous sections of this report, research shows that digital technologies can significantly improve customer satisfaction, and there is evidence that the level of digital services in HISPs is too low and thus hinders improvements in customer experience. Without more robust digital offerings, federal customers experience administrative burden that results in frustration and emotional costs, particularly around certain government services that demand sensitivity and immediacy (e.g., “requiring natural disaster victims to navigate multiple government websites with extensive supporting documentation”).[55] Low levels of digital services in federal government also produce financial costs. For example, paper forms are estimated to cost the federal government billions yearly.[56] In addition to improving customer experience, going digital saves money.

On the one hand, HISPs contend with various regulatory hurdles in improving digital services. Federal IT procurement and contracting are notoriously complex and slow.[57] Rules prevent agencies from sharing data, creating barriers to interagency service delivery, and making customers do more work.[58] FedRAMP—a program that supports the use of cloud services by the federal government—is a necessary initiative to address security risks, but it has arguably slowed cloud migration, and can be improved to support higher levels of cloud adoption.[59] Adoption of other emerging technologies that improve customer experience, such as identity verification and facial recognition, has experienced political backlash.[60]

On the other hand, slow growth of digital services is also due to HISPs not incorporating organizational best practices or taking advantage of existing resources. The Social Security Administration, for example, still requires paper signatures.[61] Legacy team structures and project management in federal government have delayed digital transformation while many in the private sector have shifted to faster, iterative ways of working.[62] GSA’s 18F—a team of technologists that helps other agencies with technical fixes and IT development—developed USWDS to offer federal agencies standardized components and best-in-class features for their websites, but too few HISP websites are powered by USWDS.[63] The same goes for other proven GSA solutions, such as login.gov and search.gov, that could offer users more consistency and integration across federal websites. Given the commercial sector’s measurably greater success with customer satisfaction, public-private partnerships reveal another missed opportunity to grow quality digital services. For instance, a commercial partner developed recreation.gov, the highest-rated HISP mobile app for both Android and iOS (4.8 and 4.9, respectively).[64] In contrast, most HISPs develop their mobile apps internally, including the lowest-rated app (3.2 on Google Play and 3.0 in the Apple App Store).

Most HISPs have expressed lip service in employing digital services to enhance customer experience, but greater digital adoption requires more substantial commitment and greater accountability by HISPs—and, as the following conclusion suggests, greater access to funding—to turn these plans into reality. As it stands, many HISPs are not fully complying with executive guidance or laws such as 21st Century IDEA.

HISPs do not have enough funding to invest in digital services.

Ultimately, federal digital transformation requires money. As a commercial leader at a July 2022 innovation forum put it, “The Federal government is taking too long to digitize citizen services and one of the reasons is because these mandates that are laid out are unfunded.”[65] The Technology Modernization Fund (TMF)—a government-wide working capital fund designed to modernize government IT—focuses explicitly on “public-facing digital services” and “cross-government collaboration/scalable services.” Yet, only five HISPs have successfully applied for and received TMF funding for these purposes.[66] Funding channels such as the TMF also offer centralized coordination for inter-agency digital services, an increasingly important attribute as the federal government focuses on priority life events that touch programs across multiple federal programs.

Critics may say that federal agencies have already received enough money and point to the TMF’s 2021 injection of $1 billion via the American Rescue Plan.[67] And yet, for a “Digital Restart” fund focused on developing digital products and services, a single Australian state a fraction the size and complexity of the United States federal government set aside $2 billion.[68] HISPs certainly need to take ownership of their role in poor customer service and weak levels of digital services, but they also need financial support to address these problems.

Recommendations

GAO should investigate HISP compliance with 21st Century IDEA requirements.

21st Century IDEA was passed in 2018, yet many of the law’s requirements remain unfulfilled by HISPs. The low level of digital services adoption impacts customer satisfaction. A GAO investigation and corresponding report would highlight these shortcomings and provide HISPs with greater incentive to accelerate adoption of digital services that have been proven to improve overall customer experience.

GAO should evaluate all 35 HISPs and determine progress against the following 21st Century IDEA measures:

▪ State of website modernization, standardization, consistency, customization, accessibility, and searchability, including which HISPs have made use of (or plan to use) shared services such as USWDS, login.gov, and search.gov

▪ Security of connections

▪ Deployment of data-driven analytics

▪ Digitization of forms

▪ Mobile friendliness of services

▪ Use of electronic signatures

GSA’s “Checklist of Requirements for Federal Websites and Digital Services” is a valuable resource for GAO to identify additional evaluation criteria.[69] GAO should also determine whether the low adoption rate of digital services by HISPs is due to particular barriers, such as funding, staffing, awareness of shared services, and poor planning by HISP leaders.

GSA’s IT Modernization COE for Customer Experience OMB should lead a one-time task force of commercial partners, customer experience experts, service designers from the federal government, and customer end users to evaluate HISP digital platforms from a customer experience lens and help HISPs implement organizational best practices.

In parallel with the GAO investigation that focuses more on legislative and policy compliance, GSA’s CX COE is well positioned to perform a one-time study through a task force of this makeup that could offer more immediate “proxy customer” feedback on a HISP’s existing digital channels, such as usability and accessibility of websites. The efforts of this task force could produce a backlog of modifications or enhancements—or a total website redesign in some cases—that specifically improve digital experiences from the customer’s point of view. GSA’s CX COE has completed extensive digital customer experience work in the past, such as developing a chatbot prototype for the U.S. Department of Agriculture and leveraging journey maps to improve customer experience at the Department of Housing and Urban Development, and is well positioned to lead this effort.[70] Furthermore, GSA’s 18F and OMB’s USDS have practitioners with expertise in applying customer experience and service design to federal digital services experience and could share lessons learned and successes across HISPs.

Additionally, including commercial experts in this effort allows the sharing of implementation strategies and plans for organizational best practices that have been successful in industry. Some of these could include establishing customer experience officers (CXOs) across HISPs or using IT product managers, who have been proven to ensure customer feedback drives an organization’s investments in digital services and support iterative software development, rapid response, and continuous improvement.[71]

OMB should update the annual PMA CX Action Plan and Capacity Assessment templates to require more thorough reporting on the progress of digital services in HISPs.

Reporting measures should demonstrate how HISP digital services improve customer satisfaction and reduce administrative burdens and costs. Plans should include timelines and milestones, specify which initiatives address the services or commitments targeted in the PMA and CX EO—including efforts to advance interagency cooperation—and share how HISPs are adopting quicker, iterative development.

As part of PMA CX reporting, OMB should also consider leveraging the recently released customer experience maturity model from GSA’s CX COE, as well as elements from the Harvard Kennedy School’s “Maturity Model for Digital Services,” which offers a framework to measure progress specifically in public sector digital services across six indicators well aligned with PMA outcomes. These include:

▪ Political environment

▪ Institutional capacity

▪ Delivery capability

▪ Skills and hiring

▪ User-centered design

▪ Cross-government platforms

The Australian government has successfully employed this model, and digital maturity indicators such as these would benefit the U.S. government’s focus on interagency collaboration and developing a more cohesive digital experience for federal customers.[72] Also, these indicators could easily be aggregated and publicized as part of the existing PMA “Customer Feedback on Federal Service Performance” dashboard.

HISPs should improve customer research data collection by integrating feedback surveys across their high-use, public-facing digital channels, if they haven’t already, and incorporating existing data from the Federal Digital Analytics Program (DAP).

In their PMA CX Action Plans and Capacity Assessments, nearly all HISPs expressed a need for better customer research and data collection. And yet, very few appear to be efficiently collecting data from digital channels such as websites or mobile apps. Collecting quality data on these platforms on a continuous basis provides ongoing direction on how to improve digital services and customer experience overall. For example, CMS recently relaunched medicare.gov and incorporated features such as enhanced navigation and a redesigned homepage based on customer feedback.[73]

For FY 2021, only 12 HISPs captured feedback through their websites. The other HISPs should take immediate steps to embed feedback surveys in their websites and apps. According to 21st Century IDEA, CIOs should be driving this effort, although they should coordinate with any newly established CXOs. HISPs could leverage Touchpoints, an existing customer feedback tool developed by GSA, to ramp up customer feedback collection on digital services. In addition to collecting digital experience quality metrics such as navigation, search, and information access, feedback surveys could include collecting data on serving disabled, underserved, and limited English proficient populations to support the Biden administration’s equity and accessibility efforts. The HISP Equity Reflection that’s currently part of the CX Capacity Assessment may be a helpful exercise, but feedback collected directly from the customer will offer a fuller picture regarding equity and accessibility across digital services.

Finally, HISPs should use data already collected from DAP to incorporate “passive” data into a comprehensive continuous improvement feedback loop for digital services. DAP captures “hidden” operational and functional data, such as visits, time spent, and abandonment rates on particular webpages, that can also inform improvements to digital platforms that support improved customer experience. For example, the State of Maryland successfully deployed user analytics to design a new, more intuitive, mobile-friendly Maryland.gov site.[74]

Congress should continue to reform regulatory frameworks that limit the growth of digital services in federal government, starting with passing the AGILE Procurement Act.

Federal IT modernization, in general, continues to be too slow, and this sluggishness extends to critical public-facing digital services at HISPs. As this report points out earlier, part of the problem HISPs face in enhancing their digital platforms is the variety of regulatory hurdles federal agencies must contend with.

Procuring solutions and working with contractors is notoriously complicated and frustrating. Fortunately, the Advancing Government Innovation with Leading-Edge, or AGILE, Procurement Act of 2022 aims to remove red tape and “advance Government innovation through leading-edge procurement capability,” such as training acquisition workers in IT and removing roadblocks for contractors.[75] This report highlights several quality, government-made digital products, but it is expensive and time-consuming for GSA or HISPs to build solutions such as mobile apps from scratch. Accessing industry-vetted software, IT solutions, and expertise needs to be an available avenue for HISPs, and the process needs to be faster and better. Congress should aim to pass the AGILE Procurement Act and get it to the president’s desk before this Congress ends early next year.[76]

Other regulatory reform efforts that support advancing digital services include improving FedRAMP by reducing duplicative security assessments, streamlining the authorization of cloud service providers, and improving the federal government’s recruitment process to acquire necessary CX and IT talent.

OMB should earmark TMF money to enhance customer-facing digital services for HISPs.

The TMF offers flexible, off-budget funding that supports continuous improvement in HISP digital services. While OMB announced in June 2022 that $100 million of the nearer-term funds from the TMF will be applied to customer experience projects (particularly those that span agencies and focus on priority life events), this funding should be earmarked explicitly for HISPs, given the greater priority designated in the PMA and CX EO.[77]

Following the GAO report and task force findings, HISPs can develop and submit detailed project proposals that demonstrate how TMF funds will be used to advance the digital “commitments” and services targeted in the executive guidance. TMF project support comes with technical oversight and best practice sharing that can increase the likelihood of success in project implementation. Additionally, when evaluating and approving project proposals, the TMF board could require adopting certain shared services and technology tools that have proven to improve customer experience, such as USWDS, login.gov, search.gov, or commercial products.

Conclusion

The federal government needs to reverse the trend of declining customer satisfaction and start to deliver online services that align with people’s everyday expectations. Nowadays, many customers expect digital experiences tailored to their needs that don’t require a user manual for basic tasks and actually do what they are supposed to do. All too often, federal sites can’t provide that. Robust digital services are particularly impactful for federal HISPs, whose missions and programming demand frequent interaction with a diverse customer base. It’s nice that improving customer experience maintains a visible and elevated position for the federal government, but not enough has been accomplished despite every administration from George H.W. Bush’s to the present claiming it as a top priority. Policymakers’ efforts—from management agendas and action plans to laws and executive orders—will continue to be ineffective if they do not take appropriate steps to catalyze digital transformation to support enhanced customer experience.

Currently, OMB and HISPs aren’t collecting enough feedback on customer satisfaction with digital services, making it difficult to continuously improve websites and apps based on customer needs. As a result, customer satisfaction remains low and declining, and the level of digital services adoption across HISPs too low.

To address these challenges, HISPs should be held accountable to comply with existing requirements for digital experiences and commit to gathering more customer feedback data that informs improvements to digital channels. Additionally, Congress should remove regulatory and procurement barriers that hamstring digital transformation, while OMB should provide improved oversight and funding to support digital customer experience.

Federal customers expect at least adequate digital experiences, and it is long past time the federal government accommodated them.

About the Author

Eric Egan is a policy fellow for digital government at ITIF. He researches digital transformation in government and how technology can help the public sector achieve mission objectives in innovative and effective ways.

About ITIF

The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) is an independent, nonprofit, nonpartisan research and educational institute focusing on the intersection of technological innovation and public policy. Recognized by its peers in the think tank community as the global center of excellence for science and technology policy, ITIF’s mission is to formulate and promote policy solutions that accelerate innovation and boost productivity to spur growth, opportunity, and progress. For more information, visit itif.org.

Endnotes

[1]. American Customer Satisfaction Index, “Federal Government Report 2021” (Ann Arbor, MI: ACSI LLC, January 25, 2022), https://www.theacsi.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/22jan_FED-GOV-Report.pdf; Forrester, “The US Customer Experience Index Rankings, 2022” (Cambridge, MA: Forrester Research, Inc., June 1, 2022), https://www.forrester.com/report/the-us-customer-experience-index-rankings-2022/RES177585.

[2]. “Office of Management and Budget,” The White House, accessed August 12, 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/; President Joe Biden, “Executive Order on Transforming Federal Customer Experience and Service Delivery to Rebuild Trust in Government,” The White House, December 13, 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/12/13/executive-order-on-transforming-federal-customer-experience-and-service-delivery-to-rebuild-trust-in-government.

[3]. Congressional Research Service, “Federal Workforce Statistics Sources: OPM and OMB,” R43590, (Washington DC: CRS, June 28, 2022), https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/R43590.pdf.

[4]. “June 2022 Medicaid & CHIP Enrollment Data Highlights,” Center for Medicaid and CHIP Services, accessed August 12, 2022, https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/program-information/medicaid-and-chip-enrollment-data/report-highlights/index.html.

[5]. “Returns Filed, Taxes Collected & Refunds Issued,” IRS, accessed August 12, 2022, https://www.irs.gov/statistics/returns-filed-taxes-collected-and-refunds-issued.

[6]. CMS, “CMS Releases Latest Enrollment Figures for Medicare, Medicaid, and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP),” press release, December 21, 2021, https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/news-alert/cms-releases-latest-enrollment-figures-medicare-medicaid-and-childrens-health-insurance-program-chip.

[7]. U.S. Small Business Administration, “Four Million Hard-Hit Businesses Approved for Nearly $390 Billion in COVID Economic Injury Disaster Loans,” press release, June 13, 2022, https://www.sba.gov/article/2022/jun/13/four-million-hard-hit-businesses-approved-nearly-390-billion-covid-economic-injury-disaster-loans.

[8]. U.S. Census Bureau, “Census Bureau Releases New Report on Veterans,” press release, November 10, 2021, https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2021/veterans-report.html.

[9]. OMB, “Managing Customer Experience and Improving Service Delivery,” OMB Circular A-11 Section 280, (Washington DC: OMB, August 2022), 2, https://www.performance.gov/cx/assets/files/a11_2021-FY22.pdf; President Joe Biden, “Executive Order on Transforming Federal Customer Experience and Service Delivery to Rebuild Trust in Government,” December 13, 2021.

[10]. “The President’s Management Agenda,” OMB, accessed August 19, 2022, https://www.performance.gov/pma; President Joe Biden, “Executive Order on Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility in the Federal Workforce,” The White House, June 25, 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/06/25/executive-order-on-diversity-equity-inclusion-and-accessibility-in-the-federal-workforce.

[11]. “Customer Experience,” Gartner, accessed August 19, 2022, https://www.gartner.com/en/information-technology/glossary/customer-experience.

[12]. OMB, “Managing Customer Experience and Improving Service Delivery,” OMB Circular A-11 Section 280.

[13]. Ibid.

[14]. “Customer Feedback on Federal Service Performance,” OMB, accessed August 19, 2022, https://www.performance.gov/cx.

[15]. American Customer Satisfaction Index, “Federal Government Report 2021.”

[16]. Ibid.

[17]. Forrester, “The US Customer Experience Index Rankings, 2022.”

[18]. OMB, “Managing Customer Experience and Improving Service Delivery,” OMB Circular A-11 Section 280.

[19]. Ibid.

[20]. “The President’s Management Agenda,” OMB, accessed August 19, 2022, https://www.performance.gov/pma.

[21]. OMB, “Managing Customer Experience and Improving Service Delivery,” OMB Circular A-11 Section 280; The White House, “FACT SHEET: Putting the Public First: Improving Customer Experience and Service Delivery for the American People,” press release, December 13, 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/12/13/fact-sheet-putting-the-public-first-improving-customer-experience-and-service-delivery-for-the-american-people.

[22]. Laura LaBerge et al., “How COVID-19 has pushed companies over the technology tipping point—and transformed business forever,” McKinsey & Company, October 5, 2020, https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/how-covid-19-has-pushed-companies-over-the-technology-tipping-point-and-transformed-business-forever.

[23]. Aaron Smith, “Government Online,” Pew Research Center, April 27, 2010, https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2010/04/27/government-online/; John B. Horrigan and Lee Rainie, “Connecting with Government or Government Data,” Pew Research Center, April 21, 2015, https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2015/04/21/connecting-with-government-or-government-data/.

[24]. Darrell M. West, “Brookings survey finds 51 percent prefer digital access to government services over phone calls or personal visits to agency offices,” Brookings TechTank, February 13, 2019, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/techtank/2019/02/13/brookings-survey-finds-51-percent-prefer-digital-access-to-government-services-over-phone-calls-or-personal-visits-to-agency-offices.

[25]. Bruce Chew et al., “Rebuilding trust in government,” Deloitte Insights (Washington DC: Deloitte Insights, March 9, 2021), https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/industry/public-sector/building-trust-in-government.html.

[26]. “Guide to the Digital Analytics Program,” GSA, accessed August 26, 2022, https://digital.gov/guides/dap; “Top Pages – analytics.usa.gov,” GSA, accessed August 26, 2022, https://analytics.usa.gov.

[27]. U.S. Congress, House, E-Government Act (E-Gov Act) of 2002, H.R.2458, 107th Cong., introduced in House July 11, 2001, https://www.congress.gov/bill/107th-congress/house-bill/2458/text.

[28]. President Barack Obama, “Executive Order 13571—Streamlining Service Delivery and Improving Customer Service,” The White House, April 27, 2011, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2011/04/27/executive-order-13571-streamlining-service-delivery-and-improving-custom.

[29]. President Barack Obama, “Digital Government: Building a 21st Century Platform to Better Serve the American People,” The White House, May 23, 2012, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/omb/egov/digital-government/digital-government.html.

[30]. “The Centers of Excellence,” GSA, accessed August 26, 2022, https://www.gsa.gov/about-us/organization/federal-acquisition-service/technology-transformation-services/the-centers-of-excellence; “Customer Experience,” GSA IT Modernization Center of Excellence, https://coe.gsa.gov/coe/customer-experience.html.

[31]. U.S. Congress, House, 21st Century Integrated Digital Experience Act (IDEA), H.R.5759, 115th Cong., introduced in House May 10, 2018, https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/5759.

[32]. Ibid.; “About – U.S. Web Design System (USWDS), GSA Technology Transformation Services, accessed August 26, 2022, https://designsystem.digital.gov/about.

[33]. U.S. Congress, House, 21st Century Integrated Digital Experience Act (IDEA), H.R.5759, 115th Cong.

[34]. OMB, “Managing Customer Experience and Improving Service Delivery,” OMB Circular A-11 Section 280.

[35]. Ibid.

[36]. “Priority 2: Delivering Excellent, Equitable, and Secure Federal Services and Customer Experience,” OMB, accessed September 2, 2022, https://www.performance.gov/pma/cx.

[37]. “The President’s Management Agenda,” OMB.

[38]. IRS Taxpayer Advocate Service, “TELEPHONE AND IN-PERSON SERVICE: Taxpayers Face Significant Challenges Reaching IRS Representatives Due to Longstanding Deficiencies and Pandemic Complications,” 2021 Annual Report to Congress, (Washington DC: IRS, June 2022), https://www.taxpayeradvocate.irs.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/ARC21_MSP_03_Telephone.pdf.

[39]. Rick Parrish, “The President’s New Management Agenda Has A Clear Approach To Strengthen Customer Experience,” Forrester, November 22, 2021, https://www.forrester.com/blogs/the-presidents-new-management-agenda-has-a-clear-approach-to-strengthen-customer-experience-cx.

[40]. Ibid.

[41]. “The President’s Management Agenda,” OMB.

[42]. Ibid.

[43]. President Joe Biden, “Executive Order on Transforming Federal Customer Experience and Service Delivery to Rebuild Trust in Government,” December 13, 2021.

[44]. U.S. Congress, House, 21st Century Integrated Digital Experience Act (IDEA), H.R.5759, 115th Cong.

[45]. “High Impact Service Providers (HISPs),” OMB, accessed September 9, 2022, https://www.performance.gov/cx.

[46]. “USWDS powered sites,” GSA Technology Transformation Services, accessed September 9, 2022, https://designsystem.digital.gov/getting-started/showcase/all.

[47]. “Federalist,” GSA Technology Transformation Services, accessed September 9, 2022, https://18f.gsa.gov/what-we-deliver/federalist.

[48]. “Our Customers,” GSA Technology Transformation Services, accessed September 9, 2022, https://search.gov/about/customers.html.

[49]. “List Of Applications and Department Partners Using Login.Gov For Identity Management,” GSA, accessed September 9, 2022, https://www.muckrock.com/foi/united-states-of-america-10/list-of-applications-and-department-partners-using-logingov-for-identity-management-98356.

[50]. “High Impact Service Providers (HISPs),” OMB, accessed September 9, 2022, https://www.performance.gov/cx; 44 U.S. Code § 3559.

[51]. Daniel Castro and Ashley Johnson, “Improving Accessibility of Federal Government Websites” (ITIF, June 3, 2021), https://itif.org/publications/2021/06/03/improving-accessibility-federal-government-websites.

[52]. GAO, “Agencies Need to Develop and Implement Modernization Plans for Critical Legacy Systems,” GAO-21-524T, (Washington DC: GAO, April 27, 2021), https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-21-524t.

[53]. Ibid.

[54]. Michael Vizard, “AWS Adds More Tools to Secure Cloud Workloads,” Security Boulevard, July 26, 2022, https://securityboulevard.com/2022/07/aws-adds-more-tools-to-secure-cloud-workloads; Mari Canizales Coache and Elizabeth Lowery, “FedRAMP Survey Results Report” (Market Connections, Inc., January 2021), https://maximus.com/sites/default/files/documents/FedRAMP_Survey_Results.pdf.

[55]. Issie Lapowsky, “Biden promised to digitize the government. Getting it done won't be easy.” Protocol, January 19, 2022, https://www.protocol.com/policy/biden-customer-experience-order.

[56]. Michael Garland, “To save billions, let's finally put government forms to work,” FCW, August 18, 2020, https://fcw.com/it-modernization/2020/08/to-save-billions-lets-finally-put-government-forms-to-work/258032.

[57]. Charli Renken, “Why Government Tech Is So Slow — and How D.C. Companies Are Bringing It Up to Speed,” Built In, March 16, 2022, https://builtin.com/washington-dc/dc-companies-government-tech-modernization-031622.

[58]. Natalie Alms, “Digital Identity Challenges Could Be a Roadblock to Improved CX,” Government Executive, June 27, 2022, https://www.govexec.com/technology/2022/06/digital-identity-challenges-could-be-roadblock-improved-cx/368639.

[59]. “FedRAMP,” GSA’s Technology Transformation Services, accessed September 9, 2022, https://www.fedramp.gov; Michael McLaughlin, “Reforming FedRAMP: A Guide to Improving the Federal Procurement and Risk Management of Cloud Services” (ITIF, June 15, 2020), https://itif.org/publications/2020/06/15/reforming-fedramp-guide-improving-federal-procurement-and-risk-management.

[60]. Daniel Castro, “IRS Was Wrong to Give In to Hysteria and Drop Use of Facial Verification to Fight Fraud and Protect Consumers” (ITIF, February 8, 2022), https://itif.org/publications/2022/02/08/irs-was-wrong-give-hysteria-and-drop-use-facial-verification-fight-fraud-and.

[61]. “SSR 04-1p: Attestation as an Alternative Signature,” SSA, accessed September 9, 2022, https://www.ssa.gov/OP_Home/rulings/oasi/33/SSR2004-01-oasi-33.html.

[62]. Charli Renken, “Why Government Tech Is So Slow — and How D.C. Companies Are Bringing It Up to Speed.”

[63]. “About,” GSA 18F, accessed September 16, 2022, https://18f.gsa.gov/about.

[64]. “Reinventing the Recreation.gov Customer Experience,” Booz Allen Hamilton, accessed September 16, 2022, https://www.boozallen.com/s/insight/thought-leadership/reinventing-the-recreation-gov-customer-experience.html.

[65]. Lisbeth Perez, “MerITocracy: Feds Making Strides in Digitization, Need Budget Help,” MeriTalk, July 27, 2022, https://www.meritalk.com/articles/meritocracy-feds-making-strides-in-digitization-need-budget-help.

[66]. “Technology Modernization Fund,” Office of the Federal Chief Information Officer, accessed September 16, 2022, https://tmf.cio.gov; “Investments,” Office of the Federal Chief Information Officer, accessed September 16, 2022, https://tmf.cio.gov/projects.

[67]. “American Rescue Plan,” Office of the Federal Chief Information Officer, accessed September 16, 2022, https://tmf.cio.gov/arp.

[68]. “Digital Restart Fund,” New South Wales Department of Customer Service, accessed September 16, 2022, https://www.digital.nsw.gov.au/funding/digital-restart-fund.

[69]. “Checklist of Requirements for Federal Websites and Digital Services,” GSA Technology Transformation Services, accessed September 16, 2022, https://digital.gov/resources/checklist-of-requirements-for-federal-digital-services.

[70]. USDA Customer Experience Center of Excellence Team, “USDA Chatbot Prototype: Using Artificial Intelligence to Connect Customers to Knowledge at Scale,” GSA IT Modernization Center of Excellence, November 13, 2019, https://coe.gsa.gov/2019/11/13/cx-update-15.html; HUD Customer Experience Center of Excellence Team, “The Journey to Affordable Housing for Seniors,” GSA IT Modernization Center of Excellence, October 28, 2019, https://coe.gsa.gov/2019/10/28/cx-update-14.html.

[71]. Frank Konkel, “Experts Call for More Chief Customer Officers in Government,” Nextgov, June 23, 2022, https://www.nextgov.com/policy/2022/06/experts-call-more-chief-customer-officers-government/368538.

[72]. Lara Stephenson, “Findings and recommendations from the Digital Maturity Indicator,” Code for Australia, November 28, 2019, https://blog.codeforaustralia.org/findings-and-recommendations-from-the-digital-maturity-indicator-e5b20ac4401b.

[73]. Lara Stephenson, “Findings and recommendations from the Digital Maturity Indicator,” Code for Australia, November 26, 2019, https://www.meritalk.com/articles/cms-improves-cx-on-new-medicare-website.

[74]. The Office of Maryland Governor Larry Hogan, “Governor Hogan Announces Launch of New Maryland.gov,” press release, June 2022, https://governor.maryland.gov/2022/06/01/governor-hogan-announces-launch-of-new-maryland-gov.

[75]. U.S. Congress, Senate, AGILE Procurement Act of 2022, S.4623, 117th Cong., introduced in Senate August 2, 2022, https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/senate-bill/4623/text.

[76]. Kirsten Errick, “Senate Committee Approves AGILE Procurement Act for IT and Communications Tech,” Nextgov, August 4, 2022, https://www.nextgov.com/it-modernization/2022/08/senate-committee-approves-agile-procurement-act-it-and-communications-tech/375404.

[77]. The White House, “OMB and GSA Announce Technology Modernization Fund Will Designate $100 Million to Improve Customer Experiences with the Federal Government,” news release, June 16, 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/briefing-room/2022/06/16/omb-and-gsa-announce-technology-modernization-fund-will-designate-100-million-to-improve-customer-experiences-with-the-federal-government/; Clare Martorana, “Everything you need to know about the TMF allocation to improve public-facing digital services,” Office of the Federal Chief Information Officer, June 16, 2022, https://www.cio.gov/2022-06-10-tmf-cx-allocation.