The Process of Creative Destruction, Illustrated: The US Retail Industry

The process of “creative destruction,” whereby new technologies and business models displace old ones, is key to growth and innovation. The evolution of the retail industry illustrates why it is beneficial and sheds light on the pitfalls of current legislative and regulatory efforts to limit it.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Key Takeaways

Contents

The Department Store: An Invention of the Industrial Revolution. 4

The Birth of Department Stores: Cathedrals of Novelties 4

The Success of Department Stores: Disruptive Competition Through Innovation. 7

An Improved Business Model: The Chain Stores 12

The Emergence of the Chain Store Business Models 13

Innovation and Efficiency of Chain Stores 14

Supersize Retail: Big Box Stores 20

The Rationale Behind Big Box Stores 20

The Disruption of Big Box Stores 22

Retail Reinvented: The Rise of Online Marketplaces 26

The Process of Creative Destruction and Online Retail 26

Competing Through Innovation: Consumer-Centric Business Models 28

Introduction

Harry S. Truman once said, “Progress occurs when courageous, skillful leaders seize the opportunity to change things for the better.”[1] Yet, few important changes occur without opposition. In the latter half of the 19th century, the department store developed as a new retail form that inevitably reduced the market share of wholesalers and smaller specialty stores. As the department store expanded, it brought new economic efficiencies, including lower costs and prices. Chain stores simultaneously emerged during this period but did not see their peak until the early 20th century when their operations grew to encompass multiple states. The formulation of these novel business practices further stimulated economic efficiencies. Consequently, chain stores’ success in the economy inspired other retailers to adapt their model and practices, thus pioneering the big box store (e.g., Walmart, Target, and Home Depot). Similar to previous stages of the retailing evolution, the big box store also generated economic benefits. As technology evolves, the online marketplaces of today further enhance the economic benefits shoppers experience.

Yet, despite the economic benefits each stage of retailing brought, retail innovators nevertheless experienced strong opposition from small businesses, political leaders, and critics. Often, critics claimed that these retailers utilize anticompetitive measures to harm smaller retailers. However, in reality, opponents feared the power of the creative destruction process that disrupts less efficient forms of retailing. Unable to innovate and match evolving consumer preferences, small shopkeepers weaponized antitrust and other policy tools to thwart innovative retailing. As Atkinson and Lind noted, “The fact is that every retail innovation in American history—from the mail-order catalog to chain stores to Internet-based home delivery—has been denounced by incumbent businesses as a threat to the American way of life, when in fact it was only a threat to their outmoded corporate models.”[2]

As a result of their fear, critics used and continue to use a host of tactics to limit economically efficient practices new forms of retailers utilize. Antitrust represents a prime vehicle for advancing this small producer protectionism.[3] Herbert Hovenkamp warned, “There’s never been any viable theory that has articulated small-business protectionism at the expense of consumers as a viable antitrust goal.”[4] Such protectionism represents a critical obstacle to unleashing the beneficial power of what Joseph Schumpeter coined “the process of creative destruction.”[5] Today, online marketplaces face the brunt of the backlash from legislators, antitrust enforcers, and anti-big-business activists in the form of regulations, lawsuits, and legislation. The Institute for Local Self-Reliance has asserted, “To restore an open, competitive online market, policymakers must … break up Amazon along its major lines of business … by separating Amazon’s third-party marketplace from its retail division, and spinning off its cloud services and other major divisions into stand-alone companies.”[6]

Antitrust has represented the prime vehicle for advancing small producer protectionism. Such protectionism represents the main obstacle to unleashing the beneficial power of creative destruction.

Department stores, chain stores, big box stores, and now online marketplaces all represent different stages of what is, each time, another step in advancing innovative retailing. Nevertheless, populist views, which weaponize the notion of “fair competition” to impose less competition and innovation at the expense of consumers, continue to attack this relentless process of displacement.

The intellectual father of this backlash is former Supreme Court Justice Louis D. Brandeis. In his day, Brandeis advanced a vision of antitrust aimed at impeding innovative retailing against what he considered a “curse of bigness.” Today, Neo-Brandeisians have identified the disruptive power of online marketplaces as a justification for a modern view of the old small producer protectionism.[7] This “Brandeisian localism” opposing disruptive innovations constituted an influential force behind the regulatory and antitrust opposition to the process of creative destruction in the retail industry.[8] Both throughout history and in the present, populist opposition to disruptive innovations of large-scale retailers combined with consumers’ attraction to innovative retailing large, innovative retailers generate tear apart the retail industry.

The story of the evolution of the retail industry is the story of disruptive innovations—or how innovative retailers “competed against luck.”[9] Despite their diligence, small shopkeepers relied heavily on luck for their success: They had a relatively small customer catchment and their profitability relied only on the business of local customers. On the contrary, innovative retailers did not just stand idly by waiting for the business of local consumers. Rather, they anticipated and sought an understanding of what consumers wanted thereby enabling their innovative retailing model to succeed on effort rather than luck. These small retailers inevitably arranged their organizational structures much the same way large-scale enterprises did to maximize efficiency.[10]

Innovative retailing captures the consumer demand for minimal transaction costs (one-stop shopping with augmented product varieties), affordable items (price-cutting economies of scale and scope), and an enjoyable experience (from nice architecture and social interactions to remote consumption). Innovative retailers’ that fulfilled consumers’ desires were able to continuously compete against luck.

If policymakers want to see continued increases in Americans’ living standards, including working- and middle-class Americans, they should abandon efforts to rein in large, innovative retailers. These efforts only help a few small businesses at the expense of the majority of American consumers.

The Department Store: An Invention of the Industrial Revolution

In Emile Zola’s novel, Au Bonheur des Dames (“The Ladies’ Delight”), Zola described the emergence of department stores that wiped out small shopkeepers in mid-19th century Paris and how the disruptive nature of department stores sent small shops into bankruptcy and poverty:

[T]he middlemen—factory agents, representatives, commission-agents—were disappearing, this was an important factor in reducing prices; besides, the manufacturers could no longer exist without the big shops, for as soon as one of them lost their custom, bankruptcy became inevitable; in short, it was a natural development of business, it was impossible to stop things going the way they ought to when everyone was working for it, whether they liked it or not.[11]

Price-cutting department stores epitomized the process of creative destruction that Joseph Schumpeter would later conceptualize as the source of economic growth and the nature of the capitalist process. Department stores, then called “magasin des nouveautés” (“novelties stores”), were the main agent of this creative destruction in the novel by Emile Zola.[12] The process of creative destruction in retail has come to the fore with department stores. The birth of department stores reveals the nature of innovative retailing—and their success can be attributed to the consumer-centric efficiencies that underpinned their business models.

The Birth of Department Stores: Cathedrals of Novelties

Following in the footsteps of the Arcade Providence, one of the first enclosed shopping malls in the United States, Aristotle Boucicaut pioneered the first department stores—another form of an enclosed store—Le Bon Marché (“The Good Deal”) in Paris in 1852.[13]The department stores’ idea of a one-stop shop was revolutionary: “Finding everything from trousers to bedsheets and dishware to hairdryers and lipstick under one roof was an idea popularized in large part at Le Bon Marché under the Boucicauts’ leadership.”[14]

The creator of the first department store realized the importance of keeping consumers inside the store in a way that predated today’s attention economy. To keep consumers inside the stores, Le Bon Marché brought many innovations and became known as “a public palace”: Made of iron and glass, the department stores featured gigantic mirrors rarely seen until then. It was clear that “one of the best features of mirrors is the influence they exert on busy days. They put waiting customers in a more satisfied frame and induce them to wait without complaint longer than they would ordinarily.”[15]John Wanamaker, the founder of the Wanamaker store in the United States, recorded his 1896 excursion to Paris and replicated the use of mirrors “from floor to ceiling” in his stores.[16] The use of mirrors thus became critical in the development of department stores.[17]

Figure 1: The new staircase in Le Bon Marché, Paris. Lithography by Charles Fichot, 1872.[18]

Department stores soon mushroomed throughout Paris as “cathedrals of consumption.”[19] Consumers not only found novel products and enjoyed low prices but also freely accessed palaces designed to attract and retain consumers for social interactions.[20] In fact, not only the novelties of the architecture but also the items displayed turned department stores into cathedrals of novelties in which innovations from the building to the shelving drove the stores’ attraction. The innovations of the department stores disrupted local shops and secured their success.

Department stores emerged in the United States beginning in the mid-19th century. Mimicking the model of their European counterparts, American department store pioneers Aaron Arnold and Alexander Stewart acquired the “Marble House” and “Cast Iron Palace,” respectively, in the 1850s and 1860s.[21] Although Stewart pioneered department stores in America when he organized the Marble House into multiple departments, others ultimately carried the gales of innovations in retail. “Stewarts was by far the largest store in mid-century America, however, in many ways, it was simply the most prominent example of a trend toward innovative retailing throughout the country.”[22]

Indeed, at the close of the decade, the two pioneer department stores had set the precedent of what defined a department store: a large store that sold a wide range of products separated by departments. Copying this precedent, Lord & Taylor (1870s), B. Altman & Company (1876), Abraham & Strauss (1883), among others—including Stern Brothers, Ohrbach’s, Inc., Bergdorf Goodman, Bonwit Teller, Best & Company, Lane Bryant, Henri Bendel, Inc., Peck & Peck, Franklin Simon, James A. Hearn & Son, and R. H. Macy—saw their inception no later than the early 20th century in New York.[23] The draw of interested consumers and the profitability of the model encouraged the further expansion of department stores from Chicago to Los Angeles.[24]

Not only the novelties of the architecture but also the items displayed turned department stores into cathedrals of novelties in which innovations from the building to the shelving drove the stores’ attraction. The innovations of the department stores disrupted local shops and secured their success.

Department stores were ubiquitous in the development of America during the Industrial Revolution. Middle-class America and modern capitalism centered on consumer preferences originated from the rise of American department stores.[25] Indeed:

Department stores in the United States democratized luxury … the principal of first-come-first-served allowed a servant to be waited upon before an heiress … Obsequious acts, such as greeting shoppers, accepting returns, and treating all equally, regardless of positions in society, were elevated to the level of public service, something highly regarded in a democratic society.[26]

The great emergence and expansion of the department store across the United States brought many economic and retailing efficiencies not seen before. Due to their profitability and efficiency, some parts of the department store model are still in use today. Departments stores were “undoubtedly a phenomenon—perhaps the phenomenon of the nineteenth century and early twentieth-century retailing.”[27]

The railroad boom of the 1840s and 1850s further funneled the development of the department store model as rail became a significantly more reliable, faster, and cheaper means of transporting products from the manufacturer to the retailers. Historian Alfred D. Chandler asserted:

The steam locomotive not only provided fast, regular, dependable, precisely scheduled, all-weather transportation but also lowered the unit cost of moving goods by permitting a more intensive use of available transportation facilities. A railroad car could make several trips over a route in the same period of time it took a canal boat to complete one.[28]

Every city in America quickly had its department stores, which themselves began pursuing their own price-cutting endeavors. For instance, Dayton’s department store in Minneapolis used its basement as a “quality discounter.”[29] Initially called the “Downstairs Store,” the discounter eventually became “Target.” [30] Discounters and membership stores such as Costco started to populate every city in America with one objective: lowering prices.[31]

Middle-class America and modern capitalism centered on consumer preferences originated from the rise of department stores.

But how can one explain the success and rapid expansion of department stores?

The Success of Department Stores: Disruptive Competition Through Innovation

The spectacular success of department stores brings “about ruin and destruction of small traditional commerce … for the ever-expanding grand magasin.”[32] This “triumphant march of modernity” leads department stores to expand rapidly.[33]

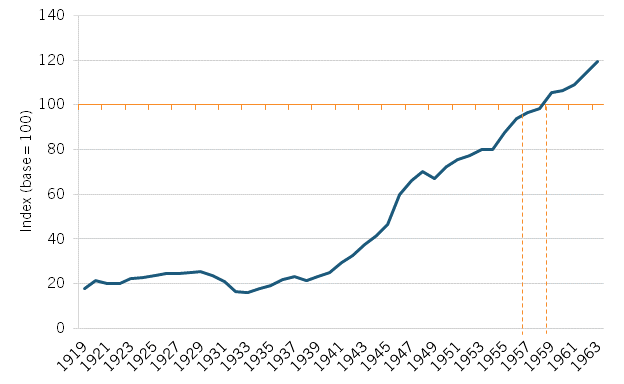

Department stores developed together with the rise of suburbs and malls, inevitably leading to a decline in disrupted small shops often located in downtowns.[34] Despite antitrust actions, the development of department stores was hardly stoppable, as figure 2 illustrates.[35]

Figure 2: Department store revenues indexed to average sales in the period from 1957 to 1959[36]

Department stores epitomize the process of creative destruction via innovative retailing. They offer new ways of selling items, thereby contributing to innovations that enable firms to outcompete competitors. As Joseph Schumpeter made clear, firm organization that maximizes consumer reach is also a form of innovation. As early as the beginning of the 20th century, the innovativeness of department stores was widely recognized: “The merchant may exercise invention in the devising of a new method of selling goods. The department store was an invention of this class.”[37]

So how did department stores emerge simultaneously in France, America, and to a lesser extent, England? One possible answer is mass production irremediably led to mass consumption: Efficient distributional facilities (e.g., railroads) enabled producers to sell an abundance of innovations of the Industrial Revolution created at a considerable scale. Michael Miller noted, for example, that France was the largest producer of cotton goods on the continent:

Mass production of [cotton goods] required a retail system far more efficient and far more expansive than anything small shopkeepers might be able to offer. Consequently, incentives on the part of producers or jobbers to stimulate buying in large lots, an initiative on the part of new merchants to purchase such batches at low prices, became a growing practice.[38]

In other words, the innovation of the Industrial Revolution (i.e., mechanization of industries) triggered a virtuous cycle whereby corporate scale led to mass production, itself requiring better and more efficient wholesalers that could offer items at a lower price and a greater scale than smaller businesses could. These innovations, which offered lower prices and managed to keep consumers’ attention through architectural prowess and social interactions, disrupted small shopkeepers. The revolution that department stores represented was as much on the shelves as outside: Low prices and an extensive range of products were offered in socially appealing and visually stimulating environments. With all their inconveniences (i.e., transportation and searching costs), small shopkeepers could not compete. Moreover, the Industrial Revolution meant that people had more money to spend while cities were growing and affordable manufactured consumer goods became more readily available.[39]

The revolution that department stores represented was as much on the shelves as outside: Low prices and an extensive range of products were offered in socially appealing and visually stimulating environments.

Department stores had many benefits, but none rivaled the primary benefit of offering consumers the lowest possible prices: The innovative retailing of department stores first and foremost, meant price-cutting for consumers.[40] As such, department stores implemented buying methods that would reduce the cost of products to as close to the cost of production as possible.[41] Since large stores required large quantities of purchases, they obtained “extremely favorable contracts” when purchasing products to fill their shelves.[42] Department stores incentivized manufacturers to reduce prices with their large-quantity purchases that enabled manufacturers to increase sales and reduce costs per unit of production.[43]Due to their purchasing power, department stores eliminated the middleman wholesaler while simultaneously lowering prices for consumers.[44]

One significant innovation of department stores was the introduction of fixed and ticketed prices. Consumers gained price transparency, and transaction costs dramatically lowered as the bargaining time virtually disappeared in an era of mass consumption and fixed prices.[45]For instance, department stores facilitated the expansion of ready-to-wear instead of tailor-made clothing.[46] As lower prices, quicker transactions, and mass production were quintessential to department stores, the rise of ready-to-wear clothing for the benefit of consumers is unsurprising.

In accomplishing their objective of lower prices, department stores increased retailing efficiency as the allocation of products to consumers increased instead of sitting idly in the supply chain. Although their purchasing power generated efficiencies, their high stock turn model, or “the number of times stock on hand was sold and replaced within a specified time period,” further incentivized low prices and greater economic efficiencies.[47]Department stores’ high stock turn model had one primary objective: to sell large quantities at low prices and margins in order to increase profits.[48]

Although it seems counterintuitive that lower prices increased profits, a 1925 survey of 650 department stores concluded that the high stock turn model reduced expenses for retailers that sold large volumes of goods.[49] For example, high-volume sales resulted in a 1.8 percent interest expense while low-volume sales resulted in 2.5 percent.[50] Thus, the high rate of stock turn reduced department stores’ total expenses. Moreover, high stock turn also increased profits. The same study of 650 department stores found that stores with annual sales of over $1 million received a net profit of 3.6 percent for every dollar, whereas those with sales of less than $1 million received only 1.9 percent per dollar.[51] The profitability reduced transaction costs as department stores sold more varieties of demanded products at lower prices.

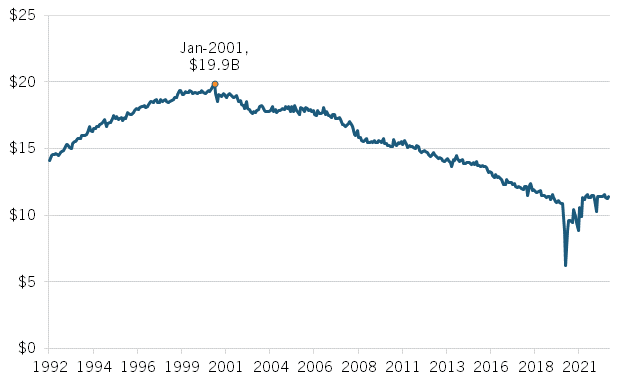

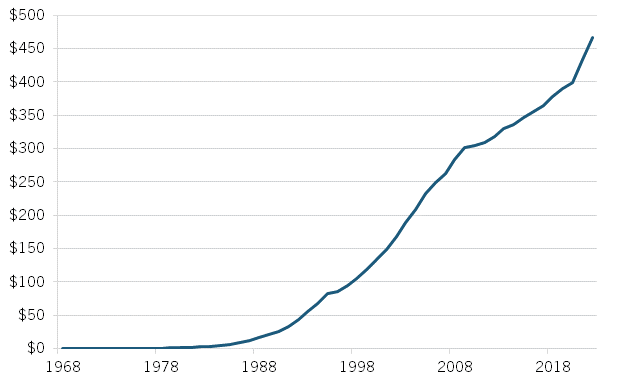

Despite the business model’s superiority in the late 1800s and early 1900s, one of America’s largest department stores—Kohl’s—was recently in talks to be sold in an economically challenging environment.[52] Competition, mostly from online commerce, has exacerbated the financial difficulties of the department store business model, as figure 3 illustrates.

Figure 3: Monthly advance retail sales in U.S. department stores (billions)[53]

While previously department stores were the disruptor, even more innovative business models—mainly online marketplaces—are now the disruptors of department stores. Nevertheless, antitrust actions have historically challenged the innovative retailing department stores represented. Department stores may have been a success story for consumers; however, they were a failure for a sufficiently large number of small shopkeepers who fostered popular pressure to tame this innovative form of retailing for the exclusive benefit of themselves.

The Regulatory Opposition to the Innovation of the Department Stores

Department stores encountered heavy scrutiny from critics—most notably from the local shopkeepers efficient department stores directly disrupted. For instance, as soon as department stores emerged in the mid-19th century, Paris shopkeepers published a petition in the Journal des Économistes.[54]They considered it “horrible” that shoppers could buy stockings, handkerchiefs, shirts, and shawls in the same establishment.[55] In response, the government restricted the variety of lines of business within a singular department store, hence limiting the development of department stores.[56] In Germany, the opposition to department stores (Warenhaüser) often conflated with antisemitism on the assumptions that Jews owned these disruptive and efficient business structures. Tax and regulations applied to Warenhaüser.[57]

More specifically, the (mis)use of antitrust for blocking the creation and development of department stores was widespread in the United States. Supported by organizations and merchants who feared competition, the Illinois Senate passed one of the first anti-department store bills despite questions about its constitutionality in 1897.[58]Although it was likely that this bill would ultimately fail to become law, it did not deter critics of department stores (i.e., incumbent small shopkeepers) from continuing their attempts to obstruct the creative destruction of retail via the development of department stores.[59]

Signaling the immense support for inefficient retailers, New York Assemblyman Barry bluntly asserted in 1897 that department stores did not have a place in the economy, as they had destroyed “numerous previously prosperous tradesman.”[60] Thus, in the following year, the New York City Council introduced a resolution imposing a $500 annual license fee on each department store department.[61]In the city of Chicago, a local ordinance targeting department stores prohibited the “sale of any meats, fish or other provisions or any intoxicating liquors in any place of business where dry goods, cloth, and other specified goods are sold.”[62] Spreading quickly across the country, this negative sentiment appeared as far as Colorado, where various social organizations demanded that the Denver City Council pass an ordinance against department stores.[63]

As the opposition grew, backlash spread to the state level as legislation limiting the practices of department stores increased. Indiana, Wisconsin, and Missouri passed bills that primarily sanctioned department stores.[64] For example, the Missouri Anti-Department Store legislation required department stores to pay a $300 to $500 tax.[65] The intense opposition against department stores throughout the country to prevent the creative destruction of less-efficient retailers limited the department stores’ practices and thus the efficiencies they offered.

Fortunately, the backlash began to subside in 1899 when the Illinois Supreme Court ruled in City of Chicago v. Netcher that an ordinance targeting department stores violated the constitutional right to liberty and property protection.[66] Following suit, the Supreme Court of Missouri ruled that Missouri's Anti-Department Store legislation violated constitutional rights in Wyatt v. Ashbrooke et al.[67]These two court cases triggered the beginning to an end of the detrimental provisions against department stores critics supported.

In Dr. Miles Medical Co. v. John Park & Sons Co., the Supreme Court made agreements between manufacturers and their distributors on the minimum resale price of the manufacturers’ products, “per se,” or automatically unlawful.[68] The Supreme Court considered those agreements “designed to maintain prices … and to prevent competition among those who trade in [competing goods].”[69]This prohibition enabled consumers to enjoy the low prices large department stores could offer often at the expense of disrupted local shopkeepers.

However, antitrust populism and the desire to protect small businesses following the Great Depression drove Congress to “punish” all large department stores due to the expansion of market power that disrupted local stores.[70] Congress passed the Miller-Tydings Act in 1937 that enabled states to enact “fair trade” laws. In other words, Congress allowed states to overrule Dr. Miles Medical Co. v. John Park & Sons Co.[71]The act exempted certain kinds of vertical price fixing from antitrust laws. The objective of Miller-Tydings was to permit states to protect small retail establishments Congress thought department stores might otherwise drive from the marketplace.

The protection of small businesses against the price-cutting practices of department stores went as far as the passing of the McGuire Act, which made the Miller-Tydings Act even stricter. In Schwegmann Bros. v. Calvert Distillers Corp., the Supreme Court struck down in 1951 the “nonsigner” provisions of state fair trade laws.[72] These statutes provided that once a manufacturer signed a minimum price agreement with one dealer in the state, the agreement bounded all other dealers regardless of whether they signed it. To overcome the Supreme Court decision of Schwegmann Bros., Congress passed the McGuire Act of 1952, which amended the Miller-Tydings Act: The “nonsigner” provisions of state fair trade laws could therefore continue at the expense of price competition and innovations large department stores exerted in the retail industry. Only in 1975 did Congress pass the Consumer Goods Pricing Act, which effectively repealed Miller-Tydings, thereby restoring the precedent of Dr. Miles.

However, in 2007, the Supreme Court overruled Dr. Miles with the decision Leegin Creative Leather Prod., Inc. v. PSKS, Inc. that the appropriate standard for testing the lawfulness of minimum resale price agreements, also known as resale price maintenance or RPM, is the rule of reason, not the per se standard.[73] Under the rule of reason, the courts evaluate the effects of a trade restraint on competition in the relevant antitrust market. If a restraint’s effects benefit competition between rival firms more than they injure competition, the restraint will be upheld. Thus, the Leegin decision means that courts will now review RPM practices on a case-by-case basis.

Opposition to department stores also resorted to the populist “anti-bigness bloc” of the Warren Court to weaponize antitrust against the development of chain stores through mergers.[74]In Brown Shoe v. United States, the Court blocked a merger between Brown Shoe and G.R. Kinney because the merger could disrupt small retail competitors.[75] Brown was the 4th largest manufacturer of shoes, with 4 percent of the nation’s production, whle Kinney was the 12th largest, with 0.4 percent of the national production.[76] The merged firm would have merely owned about 2.3 percent of the 70,000 retail outlets in the country.[77] Rejecting Brown’s litigation-created argument that the merger would not result in efficiencies given the Warren Court’s opposition to efficiencies and low prices, the Court found that the merger would result in efficiencies, enabling the merged firm to charge lower prices thanks to vertical integration. The Court blocked the merger because of efficiencies, not due to their absence. The Court stood in the path of disruptive innovations: The artificial protection of locally inefficient retailers stopped creative destruction in the retail industry.

A few years later, the Warren Court repeated the economic pitfalls of antitrust populism with Von’s Grocery.[78]The case of United States v.Von’s Grocery “was a return to Brown Shoe with a vengeance.”[79] The Court crashed down a merger that would become a city’s second-largest grocery chain but control only 7.5 percent of the grocery business in that city.[80] Von’s Grocery involved the merger of Von’s, Los Angeles’s third-largest supermarket, with Shopping Bag, the city’s sixth-largest store.[81] The expansion of department stores and the trend leading to fewer independent grocery stores—from 5,365 in 1950 to 3,590 in 1963—were enough to justify blocking the merger (according to Justice Black, who delivered the opinion) regardless of the consumer benefits, contributions to innovations, and the necessary process of creative destruction in the retail industry.[82]

In conclusion, the regulatory restrictions and antitrust populism of department stores limited the full extent of the process of creative destruction. Courts and legislatures blocked their ability to buy at a lower price (i.e., monopsony power) and to sell a virtually unlimited range of items (i.e., vertical integration) at a lower price. The populism of the time attacked the very business model of department stores. Small shopkeepers represented political forces that successfully contained the disruptive innovations of department stores.

An Improved Business Model: The Chain Stores

The department stores undoubtedly brought a range of disruptive innovations to 19th-century Western economies. Multiple brands, low prices, a greater variety of products, and ancillary conveniences, such as unique architecture and restaurants, became readily available under one roof for consumers to enjoy. The size of department stores generated scope and scale economies, which incentivized purchase and resale in large quantities.

Another business model that contributed to innovative retailing emerged at the end of the 19th and early 20th century: chain stores. With the development of the railroad and the improvement of accounting systems, retail stores re-organized themselves to become national chains.[83] Mass production and mass distribution not only drastically lowered prices—thanks to the efficiencies of scope and scale economies—but they also offered consumers a greater choice of items. Atkinson and Lind noted that “the Amazon.com of its day, Sears, Roebuck was the most important. Farmers would wait with excitement for the latest edition of the Sears, Roebuck catalog because it gave them choice.”[84]

The disruptive nature of chain stores was even greater than that of department stores on the local shopkeepers. Department stores, prior to morphing into chains, enjoyed scope and scale economies when they brought together different brands under a single, unique roof; however, chain stores pushed the logic of scope and scale economies even further. The buildings themselves were uniformized to enable replication nationwide with the benefit of massive scope and scale economies.[85] In other words, the centralized brand management of chain stores generated standardized business models across the country. While department stores left each brand operating under its roof to purchase and sell independently, chain stores centralized functions, such as marketing and purchasing, generating lower costs and thereby lower prices for the final consumers.

The disruptive nature of chain stores was even greater than department stores on the local monopolies of shopkeepers. Department stores, prior to morphing into chains, enjoyed scope and scale economies when they brought together different brands under a single, unique roof; however, chain stores pushed the logic even further.[86]

The emergence and evolution of chain stores resulted in massive efficiencies for consumers and, correspondingly, an important antitrust backlash.

The Emergence of the Chain Store Business Models

The chain stores in the United States emerged around the latter half of the 19th century. The Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company (A&P), first established as a tea and grocery shop in the 1860s, was one of the first grocery chains in the United States.[87]Following its lead, the Jones Brothers Tea Co. (1872), the Kroger Company (1882), the five grocery chain stores that became the American Stores Company—Childs Grocery Co (1888), Acme Tea Co. (1887), Geo M Dunlap Co (1888), The Bell company (1890), and Robinson & Crawford (1891)—the H. C. Bohack Company (1887), and the Gristede Bros. (1891) saw their inception in the latter half of the 19th century.[88]

Imitating the chain grocery model, Woolworth, first opening in 1879, pioneered the five and dime chains that spread across the country.[89] Alternatively, drug chains further mimicked the chain model: Schlegel Drug Store (opened in 1850), Meyer Brothers Company (1852), T. P. Taylor & Co and Jacobs Pharmacy Co (1879), and Dow Drug Co (1882).[90]Other product lines and retailers—including department stores—would inevitably imitate the chain store model.

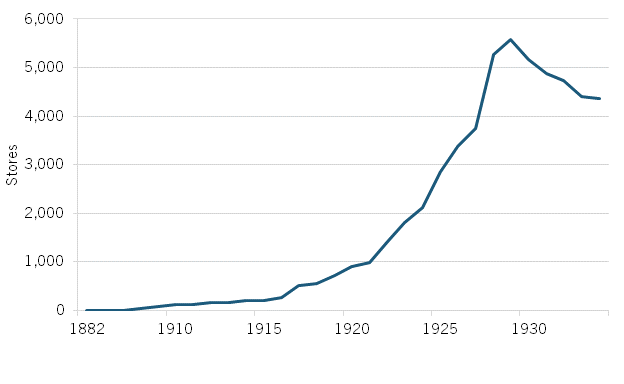

Figure 4: Kroger Grocery & Baking Co. stores (1882–1934) [91]

A period of immense growth and expansion in the 20th century followed chains’ emergence. For example, despite opening its 100th store 20 years after it started selling tea and groceries, A&P added a substantial 170 stores to its company in the two years from 1913 to 1915 and no fewer than an additional 1,600 stores from 1915 to 1917.[92] Similarly, the Kroger Grocery & Baking Company saw exponential growth in its number of stores in the 20th century. (See figure 4.)

As chain stores disrupted retailing through their innovative practices and model, many chain stores of the early 20th century would also inevitably become the target of disruption in the process of creative destruction as a new form of retailing emerged.

Innovation and Efficiency of Chain Stores

The emergence and rapid expansion of chain stores brought significant economic and retailing efficiencies throughout the 20th century. Like department stores, chain stores also aimed to offer their customers the best prices; hence, they adopted identical business models and offered the same economic efficiencies. Chain stores adopted the high stock turn model to offer low prices while maintaining high profits. As a result, they also streamlined the movement of goods in the supply chain and increased the efficiency of retailing. Moreover, they also offered a large product variety at a single location, thus reducing transaction costs for consumers. The only difference between department and chain stores was (and remains) the degree of efficiencies they offer. The economic efficiencies chains offer constantly expand as the number of stores within a chain increase.

Yet, chain stores did not rely solely on their sheer numbers to augment economic efficiencies. In their endeavor to provide lower prices, chain stores implemented a novel practice: integrating parts of the supply chain process in order to reduce costs. Integration permitted expense minimization and efficiency maximization for the benefit of consumers. For instance, instead of outsourcing warehousing functions, chains overtook the distribution process, including purchasing, storing, and delivering goods.[93]The purchase of inventory reduced the expenses incurred from products going unchecked or being damaged. The storage of inventory reduced the expenses incurred during periods of low stock resulting in the slowed distribution of products to stores and the illogical placement of stock in warehouses—both of which harmed efficient turnover rate.[94] Finally, the delivery of inventory reduced expenses incurred in unplanned and slow delivery routes.[95]Integrating these functions created an efficient system wherein chains could funnel inventory quickly from manufacturer to store to customer.

In their endeavor to offer lower prices, chain stores implemented a novel practice: integrating parts of the supply chain process. Integration permitted expense minimization and efficiency maximization for the benefit of consumers.

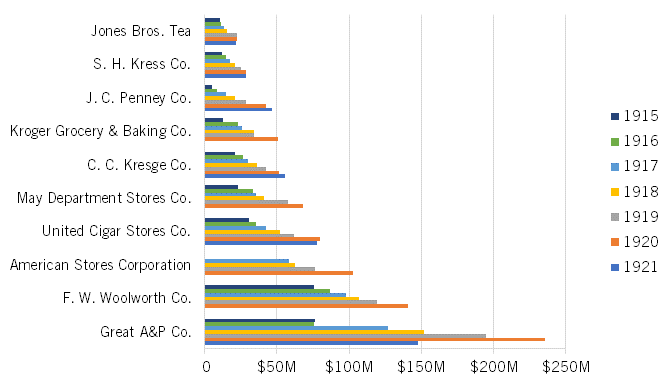

As a result, chain stores became a principal source of efficient retailing in the economy. Despite only accounting for 6 percent of all stores in 1948, chain stores accounted for approximately 23 percent of the total retail volume in the economy.[96] This is unsurprising considering some of the largest chains had increasing sales during periods of the 20th century. (See figure 5.) Consequently, chain stores further minimized prices while increasing supply chain efficiency and thus further increased the efficiency of retailing in another stage of innovative retailing in the industry’s evolution.

Figure 5: Sales of the 10 largest chains in the early 20th century ($millions)[97]

As Richard Schragger noted, the chain store revolution appeared quickly. And unsurprisingly, the disruptive power of the innovations the chain store model brought about generated a sudden anti-chain store movement: “Between 1920 and 1940, a loose confederation of independent merchant associations, local merchants, antimonopolists, agrarians, populists, and progressives sought to stem the chain expansion. By 1929, associations in over 400 cities and towns had formed to fight the chains.”[98]

The success of disruptive companies such as A&P, Kroger, American Stores, Safeway, and a national federation of independent stores (F. National) led these five companies to dominate the grocery market: The share of these top five companies in the United States increased from 4.2 percent to 28.8 percent, as table 1 illustrates.[99]

Table 1: Market share of the top five chain stores in the United States (C5 concentration ratio, 1919–1932)[100]

|

Year |

A&P |

Kroger |

Am. Stores |

Safeway |

F. National |

C5 |

|

1919 |

4,224 |

1,175 |

4.2% |

|||

|

1920 |

4,600 |

799 |

1,243 |

5.6% |

||

|

1921 |

5,200 |

947 |

1,274 |

6.3% |

||

|

1922 |

7,300 |

1,224 |

1,375 |

118 |

7.1% |

|

|

1923 |

9,300 |

1,641 |

1,474 |

193 |

8.0% |

|

|

1924 |

11,400 |

1,973 |

1,629 |

263 |

9.3% |

|

|

1925 |

14,000 |

2,599 |

1,792 |

330 |

11.5% |

|

|

1926 |

14,800 |

3,100 |

1,982 |

673 |

13.6% |

|

|

1927 |

15,600 |

3,564 |

2,122 |

840 |

1,681 |

16.9% |

|

1928 |

15,100 |

4,307 |

2,548 |

1,191 |

1,717 |

20.4% |

|

1929 |

15,400 |

5,575 |

2,644 |

2,340 |

2,002 |

24.5% |

|

1930 |

15,700 |

5,165 |

2,728 |

2,675 |

2,549 |

27.6% |

|

1931 |

15,670 |

4,884 |

2,806 |

3,264 |

2,548 |

29.3% |

|

1932 |

15,427 |

4,737 |

2,977 |

3,411 |

2,546 |

28.8% |

More generally, taxation and antitrust populism epitomized the anti-chain store movement.

The Antitrust Opposition to the Innovations of the Chain Stores

Critics of chain stores did not learn from their predecessors that attempts to protect less-productive retailers were only hurting consumers and the economy.[101] “Between 1920 and 1940, a loose confederation of independent merchant associations, local merchants, antimonopolists, agrarians, populists, and progressives sought to stem the chain expansion.”[102] The opposition to chain stores garnered an extensive range of vested interests antimonopoly populists best represented, in a similar way, Neo-Brandeisians currently best personify this opposition:

In the 1920s and 1930s, a wide range of groups and individuals opposed the chains. Unions worried about wage pressures; farmers were concerned about chain monopolies for commodities; wholesalers felt threatened as retailers increasingly integrated vertically; African-Americans feared that chains would undercut black merchants and leave the black community at the mercy of white-owned chains; and the Ku Klux Klan criticized chains for taking over small-town markets and sending money out of the South. Antimonopoly Progressives, like LaFollette, and populists, like Huey Long, agreed in their objection to chains. Of course, so did the independent merchants, represented most prominently by the National Association of Retail Grocers and the National Association of Retail Druggists.[103]

First, anti-chain store taxes emerged in multiple states in the 1930s. From California to New York, including Illinois, Georgia, and dozens of other states, more than 20 states passed anti-chain store taxes due to increasing political pressure from a myriad of shopkeepers and their employees who opposed the disruptions of chain stores.[104]

At the local level, ordinances targeting chains passed in multiple cities. For example, the city of Danville, Kentucky, passed an ordinance requiring “cash and carry” grocery stores, which were essentially chain grocery stores, to pay a higher licensing tax.[105] At the state level, by 1927, critics proposed at least 20 bills, including a Maryland law imposing an annual $500 license tax on chains.[106] Two years later, a Texas legislator’s proposal of a bill requiring chains to “invest a certain percentage of their profits in Texas’ interest” furthered the anti-chain sentiment.[107] As the negative sentiment grew, nearly 400 cities developed novel approaches to suppress the expansion and operation of chains.[108]

Further emboldening taxes against chains, the Supreme court ruled in State Board of Tax Commissioners v. Jackson that the taxation of chains did not violate any constitutional rights and was thus legally permissible.[109] Hence, this precedent set off a streak of anti-chain store tax laws in 26 states over the course of the subsequent six-year period.[110] Louisiana passed one of the most punitive tax laws against chain stores in the nation: It taxed chains according to their total number of stores nationally, not simply the number of stores in the state. A&P challenged the tax.

In the case Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Co. v. Grosjean, the Supreme Court rejected A&P’s claims. It upheld the tax precisely on the basis that there was ample “evidence bearing upon a variety of advantages enjoyed by large chains which are unavailable to smaller chains.”[111] After that tax law case, the disruptive competition of A&P became the target of a criminal antitrust case in 1946. Indeed, a federal district court and the court of appeals found A&P in violation of the Robinson-Patman Act in what was an attempt to enforce “perfect competition,” which always leads to poorer rather than a superior economic performance.[112] A&P was found guilty of using what scale offers: a monopsonistic power wherein the store can purchase large quantities at lower prices to outcompete competitors. Indeed, Judge Minton summed up the guilt of A&P:

The buying policy of A & P was to so use its power as to get a lower price on its merchandise than that obtained by its competitors.... It used its large buying power to coerce suppliers to sell to it at a lower price than to its competitors on the threat that it would place such suppliers on its private blacklist if they did not conform, or that A & P would go into the manufacturing business in competition with the recalcitrant suppliers.[113]

The same scale economies of A&P disrupted its competitors to the point they were unable to compete. The passing of the Robinson-Patman Act thwarted such disruption and slowed down the process of creative destruction for the benefit of inefficient competitors, not consumers.

As if taxes were not enough to limit chains, the same six-year period also saw the passing of fair-trade laws in nearly 42 states.[114] These fair-trade laws forced chains to maintain the retail prices manufacturers set despite the chain’s ability to reduce prices from efficiencies, as this would protect inefficient competitors from price competition.[115] Fortunately, as with all mistakes, rational actors retaliated against these anti-chain store provisions. In 1925, the Supreme Court of Kentucky ruled in Danville v. Quaker Maid that the city of Danville’s ordinance was unconstitutional on the grounds that it violated the Equal Protection Clause.[116] State supreme courts subsequently heard at least two other cases regarding anti-chain stores legislations.[117]

Furthermore, in opposition to the fair trade state laws, the New York Court of Appeals asserted in Double Day, Doran & Co. v. R. H. Macy & Co. that the “nonsigner provision of the statute [is] unconstitutional under both state and federal legislation” because it constituted unnecessary “legislative price fixing.”[118] Despite this early win, the repeal of state fair trade laws did not occur until the 1970s.[119] State fair trade laws only served to stifle the creative destruction of the retail and economic efficiencies chains brought.

Unfortunately, this period of legislative frenzy did not conclude at the state level and instead spread to the federal level.[120] Beyond the Miller Tydings Act of 1937, the main piece of legislation that upset antitrust principles to protect small retail businesses from the creative destruction of chain stores was the Robinson-Patman Act, which amended the Clayton Act of 1914 and entered into the few foundational acts—together with the 1890 Sherman Act and the 1914 Federal Trade Commission Act—that gave birth to American antitrust laws.

The Robinson Patman Act prevents a “seller charging competing buyers different prices for the same ‘commodity.’”[121]Written by staunch supporters of independent businesses, Senator Wright Patman and Joseph Robinson, the act’s main purpose to protect independent retailers was so blatantly obvious that it was known as the “Anti-A&P Act.”[122] Together with the Miller Tydings Act, which was essentially a fair trade act at the federal level, these two federal acts hampered the creative destruction in the retail sector as chain store practices became limited.[123]

Justice Brandeis proved to be the intellectual force behind the campaign to protect small businesses via the Robinson-Patman Act, irrespective of the efficiencies and innovations of large retailers. Indeed, in Louis K. Liggett Co. v. Lee, Justice Brandeis dissented from a Supreme Court decision overturning a Florida statute that taxed multi-store retailers in proportion to their number of stores.[124] Brandeis dissented from the decision, which overturned the Florida statute because the statute was designed to harm and discourage chain stores, irrespective of consumers’ interests:

The chief aim of the Florida statute is apparently to handicap corporate chain stores—that is, to place them at a disadvantage, to make their success less probable. No other justification of the discrimination in license fees need be shown; since the very purpose of the legislation is to create inequality and thereby to discourage the establishment, or the maintenance, of corporate chain stores…[125]

As a result of the Robinson-Patman Act’s design to prevent “hard competition” from disruptive chain stores in favor of a “soft competition” between inefficient incumbent retailers, a disagreement between the two federal antitrust agencies on how to enforce the Robinson-Patman Act quickly emerged.[126] While the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) aggressively enforced the Robinson-Patman Act to protect small retailers from competition, the Department of Justice’s (DOJ’s) Antitrust Division disagreed and instead encouraged competition over retail distribution—an aspect where chain stores had a considerable competitive advantage over locally inefficient retailers.[127]

The Robinson-Patman Act was the result of populist antitrust pressures aimed at lowering chain stores’ exertion of disruptive competition on local monopolies. Increasing competition was not its objective but rather protecting the existing local monopolies at the expense of consumers’ benefits and the numerous innovations chain stores brought into the retail industry.

Unlike the Miller-Tyding Act, Congress never repealed the Robinson-Patman Act.[128] Such inability to repeal a competition-decreasing and innovation-stifling act is notable because of the numerous calls of repeal from both sides of the aisle since its passing.[129] Robert Bork described it as “antitrust’s least glorious hour,” as “Congress made no factual investigation of its own, and ignored evidence that conflicted with accepted rhetoric” before passing the legislation.[130]

For instance, in SELAS CORPORATION OF AMERICA and Fram Corporation v. PUROLATOR PRODUCTS, Inc. case of 1958, the DOJ’s Antitrust Division filed an amicus brief in support of the petition for certiorari, contending that the FTC’s interpretation of the act to require a spilt-function distributor to pay the same price as an independent jobber that performed no warehouse function would impede competition in distribution and protect existing and possibly antiquated distribution systems from normal pressures of competition and innovation.[131] The DOJ’s Antitrust Division was not keen to let the FTC refrain chain stores from unleashing the power of creative destruction with aggressive enforcement of the Robinson-Patman Act, an action that would decrease, not increase, competition and innovation in retail, and more generally, in the way American consumers shop.[132]

Beyond its ability to limit competition and stifle innovation, the unfairness of the Robinson-Patman Act is patent when one scrutinizes which actor becomes liable under the act’s provisions. In that regard, the case of Kroger v. FTC is illustrative.[133]Accused of having induced a supplier of dairy products to sell at prices lower than those charged to other customers, the chain store Kroger was found by the Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit to have violated the anti-price discrimination provisions of Robinson-Patman.[134] But why was Kroger liable for merely purchasing items when it was the seller that price discriminated against the provision of the Robinson-Patman Act? In this case, the mere argument that the prices charged were offered in good faith to meet what is believed to be the competitor’s equally lower prices exempted the supplies managed from antitrust liability.[135] In contrast, the FTC and the Court of Appeals found Kroger liable for having simply been charged different prices. This case reveals the unfairness and arbitrariness of the Robinson-Patman Act. Sellers applied price discrimination and purchasers accepted it, but enforcement discretionarily exempted the contracting party (paradoxically the one charging differentiated prices) while finding the contracted party (the one subject to price discrimination) liable. The only justification for this economic unfairness and arbitrariness finds its roots in the enforcers’ distaste for intermediaries and platforms chain stores represented yesterday, and online marketplaces represent today.

Fortunately, given the ability of the Robinson-Patman Act to thwart the process of creative destruction in the retail industry, enforcers and courts have subsequently refrained from adopting an aggressive stance in enforcing the legislation.[136] Overall, “the anti-chain store movement was animated by nostalgia for an age of smaller-scale distribution, an age that by the late 1920s was rapidly falling away in the face of ‘bigness.’”[137]

Unsurprisingly, Neo-Brandeisian advocates willing to protect small retailers irrespective of efficiency considerations and innovation concerns attempt to revive the Robinson-Patman Act in order to drastically restrain the disruptive power of online marketplaces.[138] Anyone concerned with unleashing the process of creative destruction in retail should ignore these calls designed to bring the economy back to the “Stone Age.”[139]

A conjunction of mass driving, mass consumption, tax incentives, and city expansion with suburbs paved the way for the emergence of the next stage in the process of creative destruction in innovative retailing: the big box stores.[140]

Supersize Retail: Big Box Stores

Big box stores supersized American retail. The rise of these shopping “supercenters” brought mass consumption to another scale:

Supercenters are an important and rapidly growing big-box grocery retail format. Supercenters are typically larger than 180,000 square feet, combining both a large supermarket and a large mass-merchandiser within the same store. The most well-known supercenter retailer, Wal-Mart, opened its first supercenter in 1988 and is now the largest food retailer in the world.[141]

Many big box grocery retailers expand in size, thereby diversifying their already diversified lines of business to pharmacies, in-store bakers, full-service delis, bank branches, dry cleaners, and other lines of business.[142] Big box stores can either be big box grocery stores (e.g., Walmart), general big box stores (e.g., Target), big box club stores (e.g., Costco), or big box category stores (e.g., The Home Depot, Best Buy). Innovative retailing in suburban areas provide big box stores with the possibility of supersized retailing, enabling their massive scope and scale economies.

The Rationale Behind Big Box Stores

The efficiency of the chain stores led to mass consumption. This mass consumption itself called for the creation of shopping centers in the suburbs where families relocated en masse in the early 1950s.[143] The idea was to recreate the one-stop shop of the 19th-century department stores but with the convenience of accessible car parking as opposed to congested downtowns where department stores were usually located.

The 1954 tax reform that enabled retail entrepreneurs to take large deductions in the early years of shopping center construction triggered a huge interest from companies to build shopping centers in the suburbs where American families lived and looked to shop efficiently and locally. Thomas Hanchett noted that “suddenly, all over the United States, shopping plazas sprouted like well-fertilized weeds.”[144] Shopping center construction shot up drastically, from an average of 6 million square feet per year in the early 1950s to 30 million square feet from 1956.[145] In traditionally populated urban areas, supermarkets are small, with less than 20,000 square feet of grocery selling space. Shopping centers in developed suburban areas, on the other hand, have a grocery space and total selling space of 80,000 and 100,000 square feet, respectively.[146]

These shopping centers “functioned not as supplements but as competitors to downtown shopping.”[147]Soon, shopping centers would displace downtown retailers, out-competing them with low prices, more convenient shopping, and a greater variety of items.

The efficiency of the chain stores led to mass consumption. This mass consumption called for creating shopping centers in the suburbs, where families relocated en masse in the early 1950s.

Big box stores are defined as retailers that sell branded products in large, warehouse-like stores at low prices.[148] These stores emerged in the United States in the 1960s and expanded their extraordinary presence in the 1970s. In 1962, Kmart, occupying about 100,000 square feet of space, opened its first store in Michigan selling “nationally-advertised brand-name products”—including Polaroid, Kodak, General Electric, and Black & Decker products—at consistently low prices to consumers.[149] The Walmart stores similarly opened in 1962 and sold brand name products at a discount of up to 50 percent.[150] For example, it ran an advertisement that year that promoted Sunbeam coffeemakers for $13.47, 32 percent below the non-big box average of $19.95.[151]

In 1964, J. C. Penney spun off its own version of a big box store that “emphasized brand name products” at a discount in 180,000 square feet of space.[152] In the same period, specialty big box stores also began emerging in the economy. Toys “R” Us pioneered the first big box toy store and offered approximately 18,000 different toys, including name-brand toys by Hasbro, Mattel, and Fischer-Price, in a single location.[153] Barnes & Noble became one of the first big box bookstores, selling best-seller books at discounts of up to 20 percent.[154] Staples, Office Depot, and Office Max expanded the big box model to office supplies in the mid-1980s.[155] In that same decade, Circuit City and Best Buy did the same for the name-brand electronics category.[156] The rapid emergence and expansion of big box discount chain stores in the latter half of the 20th century brought new efficiencies to both the retailing industry and the overall economy. Research concludes that big box stores provide a net good for communities since they are a “one‐stop shop” for the essential products and services customers need and can obtain at a reduced cost, thanks to scale economies.[157]

What is the effect of the entrance of a big box store such as Walmart to a local retail market? Does it disrupt local retailers, hence participating in the beneficial process of creative destruction? Or do local retailers manage to survive the disruptive nature of big box stores? The answer is both interesting and counterintuitive.

Researchers have concluded that big box stores provide a net good for communities, as they are a “one‐stop shop” for the essential products and services customers need and can obtain at a reduced cost, thanks to scale economies.[158]

The Disruption of Big Box Stores

The entrance of big box stores negatively affected many mom-and-pop stores in certain towns, the disruptive innovation big box stores provide leading to small retailers being outcompeted. To paraphrase Joseph Schumpeter, the gales of creative destruction do not hit at the margin but at the very core of their business models.

But this destructive side of innovative retailing that big box stores represent (at least for locally inefficient retailers, not for the consumers) comes together with a creative side: New retailers emerge and provide complementary goods and services to the big box stores. The process of creative destruction works in full play with innovative retailing harming inefficient competitors; however, because consumer satisfaction appeals to big box stores, these retailers encourage new and more relevant local retailers to emerge.

Empirical research reveals that, counterintuitively, towns without big box stores experience a more significant number of losses of local retailers. Consumers vote with their feet and travel to neighboring towns with big box stores to enjoy highly efficient one-stop shops where new local retailers have recently emerged.[159] In other words, as competition expands geographically and innovation generalizes in the economy thanks to the creative destruction, big box stores appear as the dominant model of modern retailing.

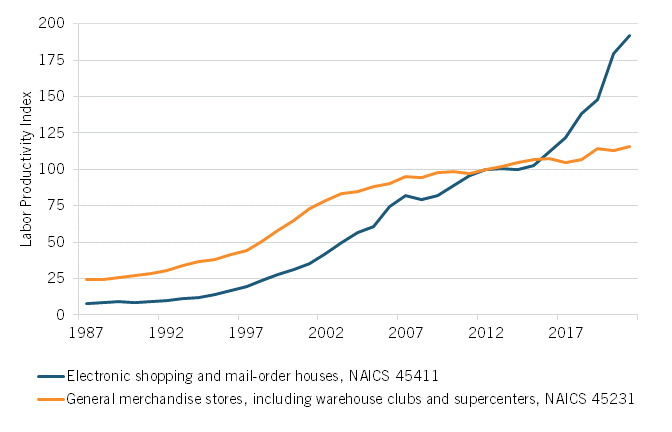

Big box stores brought similar efficiencies as did their predecessors, adopting the high stock turn model to achieve a sizable profit despite low prices.[160] For example, Walmart adopted this model and sold, on average, 14 percent below its competitors while maintaining increasing sales.[161] Its low prices drew in rising U.S. net sales. (See figure 6.) Moreover, the retailer bought directly from manufacturers with massive quantity purchases, therefore benefitting from significant discounts despite the unreasonable prohibitions of the Robinson-Patman Act.[162] Thus, big box stores similarly streamlined the movement of goods and reduced the transaction costs for consumers. Big box store retailers offered price and convenience to time-constrained shoppers while simultaneously enhancing efficiencies.[163]

Figure 6: Walmart’s U.S. net sales, 1968–2022 (billions)[164]

Big box stores represent the third stage of the retailing revolution that generated additional efficiencies for the benefit of consumers and innovation.

In addition, big box stores also integrated the supply chain process to reduce costs while maintaining efficiency. For example, Walmart integrated “new service or product development, supplier relationship, order fulfillment, customer relationship processes, and its internal and external associations” to prevent any unexpected disruptions that would increase costs.[165] As such, big box stores also transferred goods efficiently through the supply chain, hence offering the same economic efficiency that chains offered.

Big box stores represent the third stage of the retailing revolution that generated additional efficiencies for the benefit of consumers and innovation. Reducing costs at the store level enabled big box stores to increase retail productivity. For instance, big box stores implemented self-service at the store level.[166] Self-service is described as consumers receiving fewer services. For example, once found in multiple locations within a store, cash registers were placed only at the front.[167] The justification for the implementation of self-service was that it not only lowered a store’s operational expenses but also led to a “net reduction in the combined total of other expenses, such as returned goods, pilferage, training, delivery, and credit.”[168]

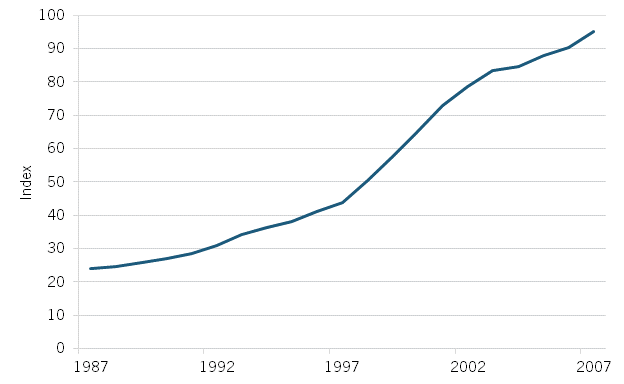

Hence, big box’s self-service approach increased its operational productivity, as employees could fulfill other tasks. Alternatively, big box stores, particularly Walmart, also experimented with the use of a universal-price-code (UPC) scanner in the 1980s to further reduce labor inputs while also increasing the number of products it could handle.[169] The installation of these scanners in two stores resulted in cashier productivity rising by more than half.[170] In fact, labor productivity for general merchandise stores, including warehouse clubs and supercenters, experienced rising labor productivity from 1987 to 2007—seeing only a decline during the recession of 2008. (See figure 7.) Thus, the experimentation with new processes and technology that minimized costs while maximizing productivity at the store level generated new retailing efficiencies and contributed to productivity growth in the economy. A McKinsey report from 2001 highlights that retail contributes on average to nearly 25 percent of the productivity growth.[171] Of that 25 percent, Walmart contributed almost 6 percent.[172] As the disruptive innovations of big box stores disseminate in the economy, productivity growth further contributes to economic growth.

Figure 7: General merchandise store labor productivity 1987–2007 (2012 = 100)[173]

Retail contributed on average to nearly 25 percent of productivity growth in 2001. Of that 25 percent, Walmart contributed almost 6 percent. As the disruptive innovations of big box stores disseminate, productivity growth further contributes to economic growth.

Consequently, big box stores found a new way of contributing more efficiencies to retailing and the economy than their predecessors did. Big box stores expanded not only domestically but also globally, thereby contributing to uniformizing the retail shopping experience due to mass consumption while also enhancing global scope and scale economies. This undoubtedly led to some critics who favor both a romanticized approach to shopping and discarding low prices in the name of cultural preservation:

The Tesco hypermarket [in the Czech town of Hradec Kralove] sits on no man’s land where town meets country … an anonymous terrain of roads, warehouses, car showrooms, fast-food drive-throughs, and big-box retail developments. It could be France, it could be the United States, it might be Germany, Mexico, Belgium, Malaysia, the U.K., or Chile. Just another global retail zone, stripped of any geographical or national character.[174]

Nevertheless, big box stores represent another stage of innovative retailing that displaced some smaller chain stores and independent stores. Data suggests that while turnover (entry and exit) of retailers demonstrates the dynamism of the retail industry, big box stores proved more successful at expanding when compared with other smaller chain stores and independent retailers:

Turnover is substantial for all retailer types. Conventional supermarket retailers opened and closed between 2 percent and 3 percent of their stores each year, with store closings being more common than openings during the sample period. In contrast, supercenter and club store retailers frequently open new stores, supercenters increased their stock of stores by more than 10 percent in 2005 and 2006, but almost never close existing stores.[175]

Big box stores represent another stage of innovative retailing that displaced some smaller chain stores and independent stores.

The Antitrust Opposition to the Innovation of Big Box Stores

The repeal of anti-chain store legislation by the 1970s prevented similar roadblocks (e.g., unreasonable taxes and fair-trade laws) for big box stores. However, big box stores nonetheless faced backlash from critics who attempted to protect less-efficient mom-and-pop shops. Critics claimed that big box stores’ practices violated antitrust laws.

Radical opposition called for the breakup of big box stores. Unsurprisingly, Walmart became the prime target of the populists’ call for such structural remedies.[176] Barry Lynn, director of the Open Markets Institute and mentor of now chair of the FTC Lina Khan, has repeatedly called for breaking up Walmart (before making the same claim again with Amazon).[177] In “The Case for Breaking Up Walmart,” Lynn argued that we need to “protect all of our fellow citizens from Walmart and other such private autocracies.”[178]

Enforcers and competitors targeted Walmart with a host of complaints regarding predatory pricing. In Wisconsin, the Department of Agriculture, Trade, and Consumer Protection accused Walmart of selling certain grocery products below cost.[179] Crest Food in Oklahoma also made similar accusations when the company filed a lawsuit alleging that the big box store had violated the Oklahoma Unfair Sales Act.[180]In 1993, three drug stores in Arkansas made similar claims against Walmart, which ultimately ended up paying a fine of $300,000 when Judge David Reynolds ruled that Walmart had indeed engaged in predatory pricing.[181]

Often, these claims of predatory pricing against big box stores stemmed from less-efficient retailers and their supporters who view big box stores’ low prices as evidence of unfair pricing practices.[182] Yet, they seldom consider the role efficient business practices have in the reduction of prices. Consequently, it is unsurprising that the court overturned the 1993 Arkansas decision only two years later in Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. American Drugs, Inc., with the assertion that “legitimate competition in the marketplace can, and often does, result in economic injury to competitors.”[183]

Furthermore, regarding the Wisconsin complaint, the FTC highlighted in an amicus brief for Snider et al. v. Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. that it does not support the Oklahoma Unfair Sales Act, as it “limits the ability of retailers and wholesalers to engage in … competitive pricing.”[184] As an increasing number of enforcers have adopted economists’ perspective that predatory pricing is highly unlikely, critics’ predatory pricing claims have declined.

However, critics have found new ways to undermine the efficiencies of big box stores. In their attempt to protect inefficient retailers and prevent the creative destruction process in retail, critics and local governments have turned to zoning regulations to limit the expansion and entry of big box stores into their communities.[185] In particular, governments use store cap ordinances to limit the size of retailers, thereby preventing the construction of big box stores.[186] For example, Arroyo Grande in California limits retailers to 90,000 square feet and, in Rockville, Maryland, officials have suggested limiting retailers to 10,000 feet of space.[187] Zoning regulations such as these significantly limit big box store entry, thus hindering competition in the local economy and the creative destruction of inefficient retailers.

The opposition to big box stores, as previous opposition against disruptive stores, relied on dubious economic arguments and the weaponization of certain laws to protect small retailers from consumer preferences and the very process of creative destruction.

If big box stores were disruptive with massive scope and scale economies passed onto customers, the next stage of innovative retailing was even more disruptive, with online marketplaces combining the technological evolution with the convenience of remote shopping.

Retail Reinvented: The Rise of Online Marketplaces

With the emergence of online shopping, one would think that past antitrust errors and historical populist anger against innovative retail stores would not repeat themselves. Yet, online stores, particularly online marketplaces, have experienced a similar pattern of reactions: first, a phase of disruption wherein consumers favor innovation in retail, then a phase of vested interests that coalesce to ban or impede the disruptors, and finally antitrust momentum leading to a backlash of the innovative retailers in the name of protecting a softer, less-disruptive form of competition.

The pattern of disruptive innovations, populist reactions, and antitrust actions repeats itself with online marketplaces, similar to what happened to department stores, chain stores, and big box stores. Critics of disruptors use antitrust history to repeat and expand errors, not avoid them. Muris and Nuechterlein noted, when referring to the Neo-Brandeisians’ attack on any sizeable online retailer: “It took several decades of diligent analysis from academics, practitioners, antitrust authorities, and courts to draw the critical distinction between harm to competitors and harm to competition. It would be a doctrinal mistake of historic proportions to blur that line again. But that is precisely what the new antitrust critics propose.”[188]

Yet, the now well-known disruptive innovations to populist reactions to antitrust actions pattern is again repeating itself with online marketplaces.

The Process of Creative Destruction and Online Retail

The first online marketplace for retailing did not emerge until 1982, with the emergence of the Boston Computer Exchange, which consisted of an online bulletin board with listings of used computers consumers could purchase.[189] Despite its pioneering approach to retailing, the next online retailer did not emerge until 10 years later when, in 1992, the Book Stack Exchange, an online retailer that sold books, became one of the first to take advantage of National Science Foundation Network’s (NSFNET)’s acceptable use policies to sell online.[190]

Starting as “Cadabra” in 1995, Amazon launched an online bookstore with an improved customer experience and books that were, on average, 10 to 30 percent cheaper than those sold at other stores, atop a sales tax exemption when customers shopped online.[191] The advent of Amazon radically changed the consumer experience online.[192] For instance, when Amazon introduced “1-Click” shopping in 1997, the transaction costs decreased radically, and it “started a long history of innovation where Amazon systematically removed the pain points in the shopping process.”[193] Radical innovations such as free shipping, generous return policies, dynamic pricing, personalized recommendations, and reviews contributed to the disruptive nature of Amazon and the advent of mass online retailing.[194] In 2000, Amazon launched its marketplace, allowing third-party sellers (including its direct competitors) to operate on Amazon and reach an increasingly large customer base.

In 2006, Amazon Web Services (AWS) provided server capacity and an unprecedented exposure to a global consumer base that enabled small retailers to compete with big competitors. AWS removed the inefficiencies of having each third-party seller use a singular computing system, which prevents a nimble integration of services (e.g., database management, payment processing, storage components, etc.). The process of creative destruction finds a concrete illustration: Online marketplaces disrupted local stores with digital innovation but encouraged the emergence of third-party retailers that better matched consumer expectations. Amazon launched an online marketplace for books. Not long after, eBay, which originally started as an auction site before adding an online marketplace, began operating in 1995.[195] Overstock, another online marketplace, did not launch until 1999.[196]

The process of creative destruction finds a concrete illustration: Online marketplaces disrupted local stores with digital innovation but encouraged the emergence of third-party retailers that better matched consumer expectations.

In the first two decades of the 21st century, a host of online marketplaces—that allowed third-party sellers—emerged: Google Shopping (2002), Shopify (2004), Etsy (2005), Wish (2010), Facebook Marketplace (2016).[197] Walmart and Target, despite operating primarily big box stores, launched Walmart Marketplace and Target Plus, respectively, in order to keep up with the emerging digital platforms that disrupted traditional players.[198] According to Digital Commerce 360, 80 of the top 100 online marketplaces launched in the last decade.[199]

At the beginning of the effective emergence of online shopping, Clayton Christensen and Richard Tedlow wrote in 2000 that “it seems clear the electronic commerce will, on a broad level, change the basis of competitive advantage in retailing.” They referred to “disruptive technologies” as the way retailers fulfill the mission of “getting the right product in the right place at the right price at the right time.” They considered, “In retailing … Internet retailing marks [a new] disruption. A diverse group of Internet companies … are poised to change how things are bought and sold in their markets. These newcomers pose powerful threats to competitors with more conventional business models.”[200]

Experts and officials unsurprisingly underestimated the motivation of digital retail disruptors to bring their disruptive technologies into the mainstream markets, thereby radically outcompeting offline chain stores.[201] Digital retailing undoubtedly represents a radical form of disruptive innovation that shattered competitors unable and unwilling to adapt, adjust, and compete with low-cost, high-productivity online marketplaces. Now, the disruptive innovations of online marketplaces enable them to outcompete less-disruptive retailers forced to adjust or bow out of the market altogether:

Call it “apocalypse.” Call it “disruption.” Call it “revolution.” Whatever you call it, it is sweeping through retail, destroying old established brands, and changing the very experience of shopping. In 2016, Sports Authority shut down 460 stores, Walmart closed 269, Aeropostale closed 154, Kmart/Sears closed 78, Ralph Lauren closed at least 50, and Macy’s closed 100. The wave of destructive accelerated in 2017 with more than 8,000 store closings … Bankruptcy filings by US retailers nearly doubled in 2016 … It is clear that retail as we know it is changing, and with it, the very experience of shopping.[202]

Online marketplaces naturally have a global market to reach. Consumer demand drives the need for the increasingly productive efficiency of online stores. Consumers expected low prices, quicker shipping, a limitless variety of items, and more secure transactions that online marketplaces disruptively fulfill. The digital retail revolution epitomizes the process of creative destruction—displacing incumbents and creating more opportunities for third-party sellers in online marketplaces that offer competitive prices and broader choices.

Consumer demand drove the need for the increased productive efficiency of online stores. Low prices, quicker shipping, a limitless variety of items, and more secure transactions were consumers’ expectations that online marketplaces disruptively fulfilled.

Competing Through Innovation: Consumer-Centric Business Models

Amazon claims to “be the most customer-centric company on Earth.”[203] But what does it mean for an online department store to be “customer-centric”? It essentially means reducing defects in the distribution system to reduce the cost structure, which enables lower prices, better customer service, greater customer choice, and a dedication to offering customers innovative products and services.[204] This commitment helped online marketplaces develop a cost structure reduced to the extent that offline stores were unable to match, hence disrupting offline stores, leading most to bankruptcy and forcing many to adjust and compete through innovation.