New BEA Data Shows the Continued Collapse of Greenfield FDI, Putting the Lie to the Notion That the U.S. Is Attracting Global Investment

As Congress debates critical competitiveness legislation (including the CHIPS ACT) to, among other things, provide incentives for more investment in America, new data from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) can shed light on the state of investment in America. Per BEA data, the United States is in a dismal position when it comes to attracting investment in new or expanded foreign facilities as greenfield FDI (FDI to establish or expand operations in the United States) has fallen by more than 90 percent since the 1990s. Congress must recognize and address this issue lest the United States ceases to be a destination for productive investment by foreign companies entirely and thereby loses ground to foreign competitors.

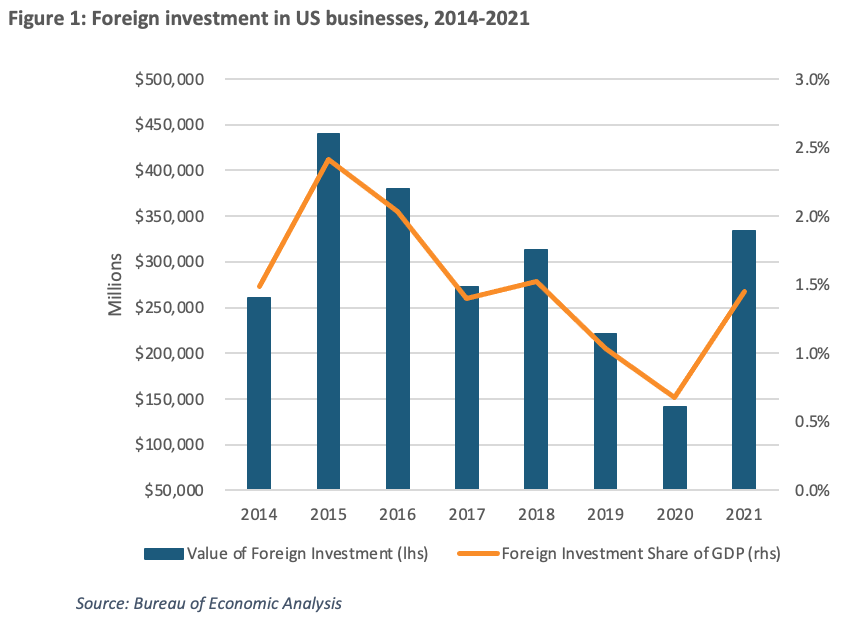

The BEA recently released data on inward FDI in 2021. FDI from allied nations is usually welcomed since it means foreign companies invest in America and often transfer technology to our shores. FDI has fluctuated over the past eight years, generally falling, but increasing from $141.4 billion to $333.6 billion in the last year (Figure 1), with the industries receiving the most FDI being Pharmaceuticals and Medicines ($58.7 billion), Real Estate and Rental and Leasing ($43.8 billion), and Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services ($37.9 billion). This marks the first increase in inward FDI since 2017-2018, and $333.6 billion is the highest single-year figure since 2016 ($379.7 billion). While this increase is a promising development, the FDI situation is less rosy than it first appears.

The share of FDI going to new or expanded facilities in the United States continues to shrink. Foreign companies appear willing to purchase existing U.S. company assets but not very willing to build new facilities or expand existing ones in the United States.

As of 2014, the BEA separates FDI into three categories: acquisition (the purchase of an existing business), establishment (the creation of a new business), and expansion (investments in an already-established business). Establishment and expansion—called “greenfield expenditures”—involve a direct investment in the productive capacities of the receiving economy. In contrast, acquisition only consists of transferring ownership to a foreign party. Therefore, it is these greenfield investments that are most important and desirable.

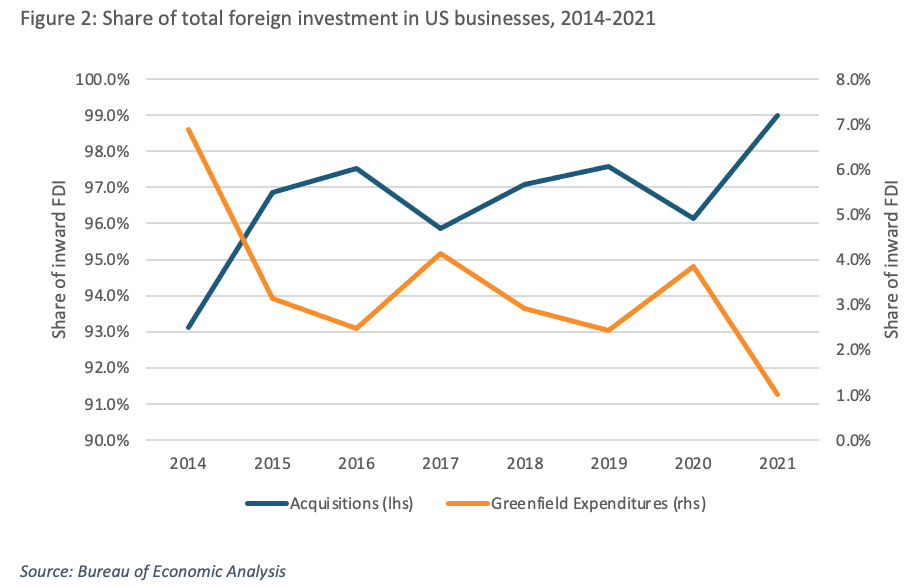

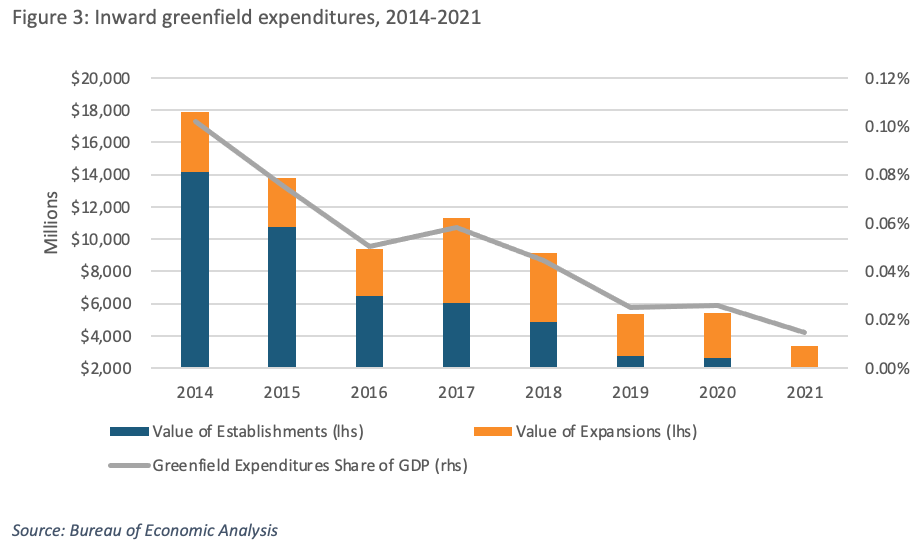

In terms of absolute value, as a share of total inward FDI, and as a share of GDP, greenfield expenditures are falling from their already minuscule starting point (Figures 2 and 3). Despite maintaining a relatively constant and small share of inward FDI in the second half of the previous decade—hovering around 2.5 to 4.0 percent—greenfield expenditures plummeted to just 1.0 percent in 2021.

Greenfield expenditure dynamics look even bleaker when considered on their own in absolute terms and as a share of GDP. The fall in inward greenfield expenditures between 2015 and 2020 was more persistent than that for inward FDI in general, and greenfield expenditures did not experience the notable increase in 2014-2015 that inward FDI in general did. Moreover, whereas inward FDI has recovered to its highest value since 2016, greenfield expenditures continued to fall in 2021. Greenfield expenditures are now just $3.4 billion in total value and 0.01 percent of GDP. These figures are an astounding 81 percent and 90 percent below their 2014 values, respectively. Thus, while inward FDI appears to have made a welcome recovery in 2021, the same cannot be said of the types of FDI that account for direct expansions of productive capacities.

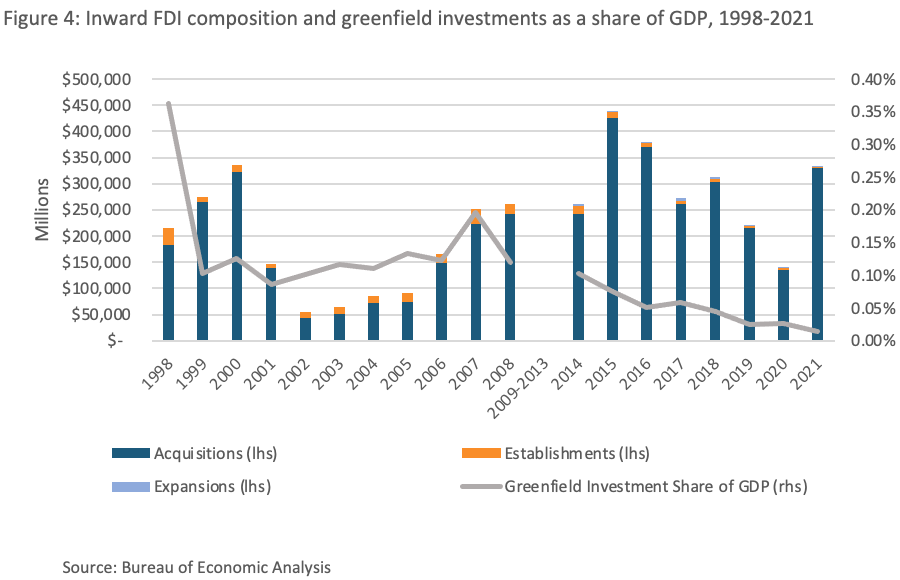

The fall in greenfield foreign investments in the United States is further illustrated in Figure 4. In 1998, the total value of establishment FDI was 18 percent of the total value of acquisitions, compared to just 0.5 percent in 2018. Furthermore, although initially small, the value of greenfield expenditures relative to GDP fell 96 percent. The BEA did not collect survey data for 2009-2013 and did not track expansion expenditures until the survey’s resumption in 2014. As such, greenfield expenditures prior to 2014 are simply equal to establishment expenditures, and the decrease in greenfield expenditures, both in absolute terms and relative to GDP, is therefore almost certainly understated.

The largest foreign providers of greenfield investments were Canada and the United Kingdom. Canada invested $234 million in establishment FDI and $272 million in expansion FDI, which mark the second most and most among foreign countries, respectively. The UK invested $301 million in establishment FDI and $30 million in expansion FDI, which mark the most and second most, respectively. However, data was not released for several of the United States’ top trading partners to avoid revealing private information about individual companies. Among the United States’ top trading partners, 2021 establishment and/or expansion data were not made available for Mexico, China, Japan, Germany, and South Korea.

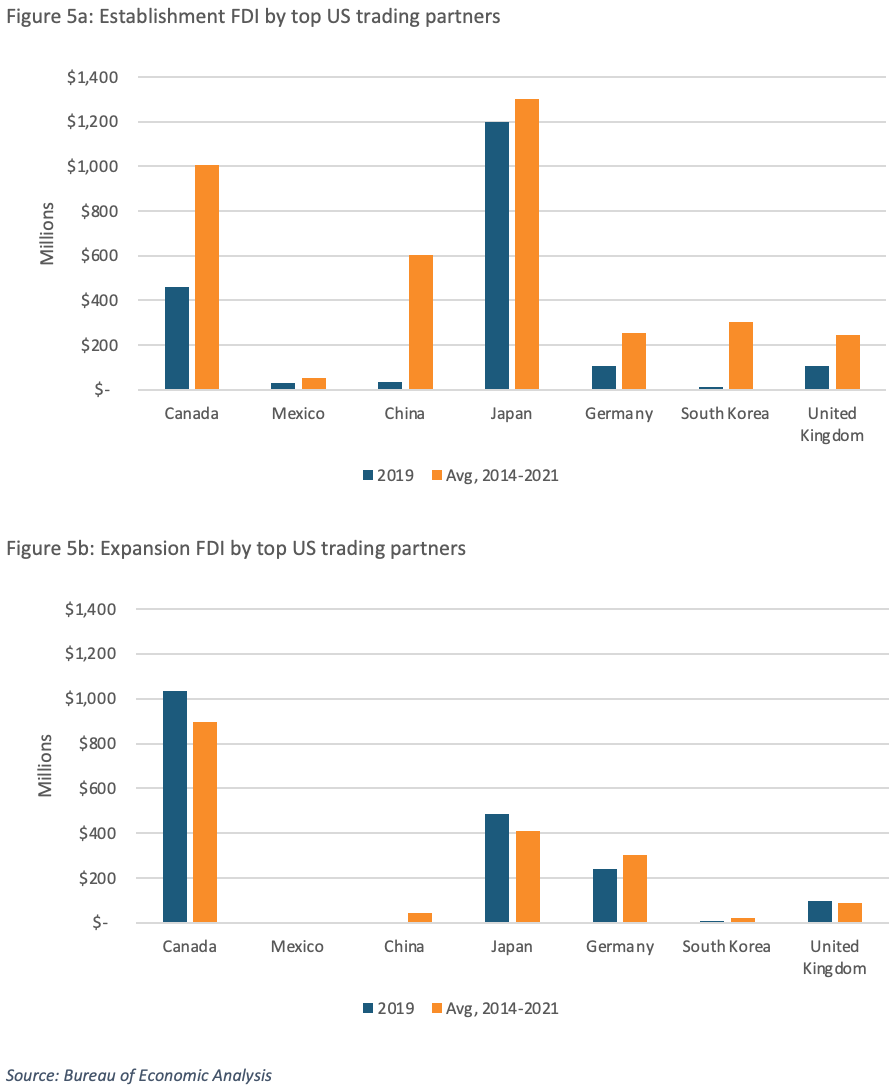

Figures 5a and 5b provide establishment and expansion data, respectively, for the United States’ top seven trading partners both in 2019 (the latest year for which data is available for all partners) and as an average of available data between 2014 and 2021. Japan was by far the largest establishment FDI investor in 2019 and the largest establishment investor on average between 2014 and 2021. In addition to being the largest expansion FDI investor for which there is available data in 2021, Canada also led in this type of FDI in 2019, and its average expansion expenditure between 2014 and 2021 was more than twice that of Japan, the next largest investor. On the other hand, Mexico, China, and South Korea invest very little in greenfield expenditures in the United States. This is especially true of expansions, in which Mexico and China did not make any investments and South Korea only invested $9 million in 2019.

The fall in inward FDI from China is especially pronounced. Between 2014 and 2021, China’s FDI in the United States fell 84.8 percent. In contrast, FDI from Canada fell 12.9 percent, from Japan rose0.2 percent, from Germany fell 20.6 percent, and from the UK rose an incredible 161.7 percent. The significant decrease in FDI from China can be attributed to the Trump administration’s warranted suspicion of the country’s investment in the United States and specifically its acquisition of US companies. This was exemplified by the passage of the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act of 2018, which broadened the President and the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States’ ability to review and block foreign investment for national security reasons. Between 2014 and 2017, China’s FDI in the United States increased from $1,895 million to $14,570 million. The following year it was just $1,634 million, and in 2019 it was $652 million.

This is not to say that acquisitions cannot result in increased productivity or output for the acquired business. For one thing, a foreign owner may introduce new production processes and techniques that are productivity-boosting, and the owner may be able to introduce the business into international markets that it would otherwise not have joined. Secondly, an acquisition may coincide with or be followed by greenfield expenditures to expand market activities once a foothold has been established (although this is not apparent in recent data for actual greenfield FDI). Thus, it is plausible that increased acquisitions may positively affect the receiving economy’s productive capacities.

Nonetheless, the fact remains that greenfield expenditures are only a marginal and decreasing part of total inward FDI, and they are plummeting both in total nominal value and relative to GDP and inward FDI in general. It is time for Congress to recognize this shortcoming and focus on dramatically increasing the United States’ attractiveness for greenfield investment.

Editors’ Recommendations

September 23, 2013

What Really Is Competitiveness?

March 31, 2009