How Progressives Have Spun Dubious Theories and Faulty Research Into a Harmful New Antitrust Doctrine

To advance their goals of economic redistribution, progressives—relying on faulty research, half-truths, and erroneous claims—have delegitimized the long-accepted “consumer welfare” approach to antitrust and generated a groundswell of support for a new “public interest” standard that seeks to protect competitors, especially small businesses.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Key Takeaways

Contents

Shifting the Overton Window. 3

Tactics to Shift the Window. 6

Step 1: Tie All Economic Problems to the Rise of “Monopoly” 6

Step 3: Use Attacks on Big Tech as a Stalking Horse for Later Attacks on Big “Everything” 8

Myth 1: Industry Concentration Levels Have Increased to Dangerous Levels 8

Myth 2: Profits Have Increased to Dangerous Levels Because of Market Concentration. 9

Myth 3: Price Markups Have Increased. 10

Myth 4: Market Concentration Has Caused the Number of Start-Ups to Fall 10

Myth 5: Superstar Firms Have Gained Market Share by Unfair Means and Harm Economic Welfare 11

Myth 6: Internet Platforms Are Welfare-Reducing Monopolies 12

Myth 7: Market Concentration Has Caused Labor’s Share of Income to Fall 12

Myth 8: Big Technology Companies Create Innovation Kill Zones 13

Overview

Ever since Joseph Overton, who was a scholar at the Mackinac Center for Public Policy, developed his concept of the importance of shifting the window of what is acceptable public policy, the idea has become foundational for thinking about policy change.[1] Overton argued that policymakers will not consider ideas that are outside a certain window of acceptability; and when that is the case, advocates of alternative policies must first work to change the window—either to widen it, so their view is seen as reasonable and acceptable, or to shift the entire window, so competing views unacceptable and their views are accepted. For the last decade, progressives have been engaged in a sustained and successful campaign to both shift the Overton window on antitrust—to delegitimize the accepted approach that is based on the long-established consumer welfare standard—and to win acceptance for a new one based on a so-called “public interest standard,” a core component of which is protection of competitors, especially small business.

This report discusses the new and old windows, and briefly examines a number of myths based on false assumptions and misguided inferences that progressives by and large have been able to successfully seed into policy debates.

Shifting the Overton Window

In the 1980s, the Overton window on antitrust was framed around four key principles, accepted and embraced by both liberal and conservative antitrust scholars:

1. Large firms are not inherently problematic.

2. In some cases, market power can lead to a decrease in economic welfare; in other cases, an increase. Each case must be evaluated on its merits.

3. Antitrust should protect competition, not competitors.

4. The goal is to promote overall economic efficiency, especially consumer welfare and dynamic efficiency (innovation).

It was precisely this antitrust window that prevented progressive, self-proclaimed “neo-Brandeisians” (after the tradition of former Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis, who sought to hold back the rise of the early 20th century industrial economy and argued that bigness was the “mark of Cain”) from ascribing to antitrust laws inappropriate policy goals. One of these unwise goals would have been to transform antitrust enforcement so that most large firms would have been broken up, and most of those that remained would be subject to utility-style economic regulation. The insulation by antitrust laws of the “small dealers and worthy men” from the process of competition and innovation was both a detrimental objective and an historical error in the antitrust jurisprudence.[2] Fortunately, policymakers and judges moved away from Brandeis’ failed refrain and economic misconceptions, which made possible American companies’ quest for efficiency and innovation under more reasonable antitrust enforcement.

Over the last 15 years, as the centrist economics of presidents John F. Kennedy and Bill Clinton have fallen out of favor among liberal Democrats, neo-Brandeisians have resurfaced to unearth old jurisprudence commonly perceived as errors from the past, asserting that virtually all economic problems stem from one cause: large corporations. Robert Reich summed up the view when he wrote that increased concentration has “resulted in higher corporate profits, higher returns for shareholders, and higher pay for top corporate executives and Wall Street bankers—and lower pay and higher prices for most other Americans. They amount to a giant pre-distribution upward to the rich.”[3] Roosevelt Institute scholar Nell Abernathy wants antirust to “tame the corporate sector.”[4]

This has led to a proliferation of screeds against bigness: Tim Wu’s The Curse of Bigness, Matt Stoller’s Goliath: The 100 Year War Between Monopoly and Democracy, Jonathan Tepper’s The Myth of Capitalism: Monopolies and the Death of Capitalism, Zephyr Teachout’s Break ‘Em Up: Recovering our Freedom From Big Ag, Big Tech and Big Money, Barry Lynn’s Cornered: The New Monopoly Capitalism and the Economics of Destruction, and perhaps the book with the catchiest, if not the most eloquent title, Sally Hubbard’s Monopolies Suck: 7 Ways Big Corporations Rule Your Life and How to Take Back Control. It should go without saying, but these books almost all start with a description of an idealized world before the 1980s, when corporations were supposedly much smaller and everyone else much better off. A host of economic problems that have transpired since then are all blamed on the rise of both so-called monopolies and a new corrupt school of antitrust, enabled by craven antitrust scholars in the pocket of big companies. And like a three-act play, the finale involves the neo-Brandeisians arriving to save us and restore some long-lost American dream by taking the antitrust hatchet to big, bad corporations. Nice (old) narratives, terrible public policy analysis (again).

The neo-Brandeisian project is not about efficiency, innovation, consumer benefits, or American competitiveness; it is about “values.” The core value is deconcentration for the sake of it.

To be clear, the neo-Brandeisian project is not to improve the economy with antitrust. It is to limit the size and economic influence of large corporations, regardless of whether it hurts or helps the economy, competitiveness, workers, and consumers.

The neo-Brandeisian project is not about efficiency, innovation, consumer benefits, or American competitiveness; it is about “values.” The core value is deconcentration for the sake of it—almost always without tangible benefits, and with a certainty of considerable costs and stifled innovation. But again, the neo-Brandeisian project is not about making economic sense from a perceived antitrust problem; it is about achieving the populist goal of moving to an economy with many fewer large businesses. According to neo-Brandeisians, because small is beautiful, nearness trumps competitiveness, nostalgia prevails over innovation, and slogans overcome analysis. Progressives have indeed embarked on a fight for values. But it is far from certain that most Americans embrace these questionable values—and it is undoubtedly clear that American competitiveness will suffer from these unnecessary political infightings.

But progressives face a key political challenge in fulfilling their agenda to radically redistribute wealth and income in America: the U.S. Senate, or more specifically the filibuster rule. For as long as progressives must get 60 votes in the Senate to achieve their policy agenda, they know that the odds of success are quite limited, to say the least. It would be hard to turn many industries into regulated ones, or to raise the corporate income tax, or to require companies to have workers on their boards, or other long-held progressive goals, when it comes to the

corporate sector.

Therefore, they understand rightly that the executive branch is their only option for achieving their redistributionist goals, and therefore antitrust enforcement is their ideal tool of choice, as it does not depend on congressional enlightenment. The open-textured provisions of the Sherman Act could indeed allow for a shift in the interpretation of antitrust laws, only with a change of mindset in the Federal Trade Commission or the Antitrust Division of the Department of Justice (DOJ). Both antitrust authorities can be influenced at arm’s length, contrary to the institutional hurdles inherent to the passing of laws in Congress. Neo-Brandeisians act strategically, and their efforts have been successful in shifting the Overton window, as evidenced by the recent cases against large tech companies.[5]

However, these efforts have also worked, as evidenced by the current efforts of House Antitrust Subcommittee Chair David Cicilline (D-RI) and Senate Antitrust Subcommittee Chair Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) to change antitrust laws to make it easier for a Democratic administration to win antitrust cases in court. And they know, just as the muckrakers who went after Standard Oil knew, that to make progress in Congress, there needs to be a villain that voters can identify, and this case it is “big bad tech” (or more specifically, “big bad Internet companies”). First, big tech; then big business generally.

For neo-Brandeisians, just as for Brandeis himself, bigness was not a blessing in the form of more innovation, stronger international competitiveness, better jobs, and higher productivity. It was a curse keeping America from realizing its true destiny of being a social democratic country.

By aggressively going after large corporations and ideally breaking them up into smaller companies, the neo-Brandeisians would not only, in their mind, achieve a giant redistribution downward to the working class, but cripple the political power of big companies, paving the way later for their dominance of not just the House, but also the Senate.

But the neo-Brandeisians face a key challenge: the Overton window. As House antitrust staffer Lina Khan wrote in the progressive Democracy Journal, “America’s monopoly problem today largely results from a successful campaign in the late 1970s and early 1980s to change the framework of antimonopoly law.”[6] In other words, the window changed then, partly due to the rise of the influence of the Chicago school of antitrust in the 1970s, and also because of the rise of new, more quantitative and sophisticated industrial-organization scholarship, as well as changes in the structure of the U.S. economy, particularly globalization.

Observing that the window could be changed again a decade or so ago, a significant group of neo-Brandeisians began a campaign to move the previously accepted ideas to outside the Overton window and replace them with their own. But these efforts represented not only an Overton window change to new, original directions, but also a pendulum swing back to the old, disparaged policy choices and judicial errors made in the post-war era—that were fortunately given good riddance to.

Their goal was to shift the window to the following:

1. Large firms (which neo-Brandeisian activist Matt Stoller calls “Goliaths”) are inherently problematic.

2. In all cases, market power leads to a decrease in economic welfare. There is need to evaluate each case on its merits.

3. Antitrust should protect competitors, especially small businesses, in order to create a society composed of “independent yeomanry.”[7]

4. Antitrust should be guided by the “public interest” standard,[8] which is pretty much whatever progressives decide it should be, including preserving jobs, reducing income inequality, protecting small firms, addressing climate change, improving racial justice, boosting free speech, reducing corporate political power, and even improving happiness.[9]

For these neo-Brandeisians, just as for Brandeis himself, bigness was not a blessing in the form of more innovation, stronger international competitiveness, better jobs, and higher productivity (even though it brings all those things).[10] It was a curse keeping America from realizing its true destiny of being a social democratic country, with the people controlling the means of production, and most people working for small, independent businesses.[11] They argued that big companies should be broken up—and wherever that is not possible because the economic costs would be too great, they should either be regulated as a public utility or replaced with government-owned companies.

And shift the window they had to do, because under the prior window, it was hard to make the case that most big companies, including platforms, were harming consumers (the prior bottom-line standard). As neo-Brandeisian advocate K Sabeel Rahman wrote:

In contemporary antitrust regulation, however, the central question is whether concentrations of economic and market power enable extractive or unfair consumer prices. On that metric, it is hard to show how Amazon and other Internet companies use power in harmful ways. If these companies lower prices and increase access for consumers, how could they be considered dangerous?[12]

Indeed, if they had wanted to achieve their goal of rejecting 120 years of economic evolution from small farms and small shops to large enterprises, they would have had to shift the window away from economic and consumer welfare and toward something else—what they called the “public interest standard.” This would have been a shift in the window of significant proportions, considering that within the antitrust community, there was widespread and strong support for the conventional framing.

Tactics to Shift the Window

So how were the neo-Brandeisians to succeed? There were three key steps.

Step 1: Tie All Economic Problems to the Rise of “Monopoly”

It would have been hard to shift to a neo-Brandeisian Overton window had the U.S. economy performed well over the previous two decades. But after the recession of 2001, a host of economic problems—including a decline in productivity and wage growth, a slowdown of new-firm formation, and a growth in income inequality—made for a fertile field for neo-Brandeisian attacks on big business. Even though there were a host of causes behind these maladies (including the rise of China, increases in corporate short-termism, government underinvestment in the factors that drive growth, including education, and others), the neo-Brandeisians were not ones to let a crisis go to waste. Virtually any and all economic problems would now be laid at the feet of large corporations, which were now considered “monopolists.” Neo-Brandeisians did not bother so much about detailing in which markets these companies were monopolists—as long as they were repeatedly and unhesitatingly labelled as “monopolists.”

This demonstrates one way to shift the Overton window. The most vocal neo-Brandeisian institution, The Open Markets Institute, depicted market realities in a rather “gross” way in order to catch public attention. (See figure 1.) No need for nuance or analysis.

Figure 1: “A helpful chart,” tweeted by Open Markets Institute, November 19, 2020

If the devil lies in the details, then neo-Brandeisians got rid of (economic) details so that the devil could be more easily pointed out—these multiple monopolists monopolize whatever markets they operate into. A constant barrage of tweets, op-eds, studies, and books paved the way for most of their claims to become conventional wisdom, even though as the Information Technology and Information Foundation (ITIF) and others have shown, most were myths not supported by actual data or studies.

Step 2: Lie With Statistics

Showing that big corporations were the cause of all things bad economically and socially required clever manipulation of statistics because, were the evidence presented objectively, it would have failed to make their case. As such, they used a number of techniques to make journalists, the public, and elected officials think that “monopoly” had grown into a curse. One was to imply that correlation was causation. Neo-Brandeisians constantly talked about how the decline in new firm start-ups was caused by an increase in industry concentration, when in fact it was not.

Another was to use misleading methods, such as when scholars argued that industry price markups (a measure of economic concentration) had vastly increased. In fact that increase was not real. Rather, the scholars accounted for the significant increase in intangible capital firms used (such as research and development (R&D)), thus artificially undercounting costs.

Another was to point to statistics and simply imply that it was related to monopoly. For example, it is now commonly held that the decline in the share of national income going to labor is caused by an offsetting of the increase going to capital (when in fact, most of the increase goes to rental income, including to homeowners).

None of these nuances were to get in the way of their campaign to shift the Overton window.

Step 3: Use Attacks on Big Tech as a Stalking Horse for Later Attacks on Big “Everything”

Finally, the neo-Brandeisians needed a villain to demonize. “Big Tobacco” would no longer suffice, as few people now smoked. Big Pharma might work, but too few people really understood the industry. Big Chicken, Big Beer, Big Broadband; these wouldn’t do the trick, even though they now had the label applied to them. As Internet platforms such as Google, Facebook, and Amazon became larger and more ubiquitous, they became the perfect targets for the neo-Brandeisian campaign. If the neo-Brandeisians could just convince enough Americans that they were getting harmed (i.e., they were “[paying] with their data”) by the companies providing either free services or incredible convenience, the doors to an Overton window shift would be open (not to mix metaphors). Data-driven companies were the greatest dangers to American society, the argument went in due proportion.[13] What they did not say—but was true—is that the attack on “Big Tech” was stalking horse for a broad-scale revision of the nation’s antitrust laws for Big Everything Else.

Myths

Neo-Brandeisians have spent that last decade promulgating a series of myths related to the industrial organization of big companies in order to paint as dire a picture as possible. As we noted in ITIF’s “Monopoly Myths” series, most of these claims are either wrong or significantly overstated.[14] The problem, however, is that in the echo chamber that pretends to be objective policy discourse, these ideas have by and large become conventional wisdom, even among non-Brandeisians—which is precisely what neo-Brandeisians want. For example, we all know that an increase in economic concentration causes a decline in start-ups; the fall in the share of income going to labor is caused by concentration; price markups, profits, and concentration have skyrocketed; “superstar” firms only exist from predation; and Big Tech creates “innovation kill zones.” The problem is all of these claims are either wrong or vastly overstated.

Myth 1: Industry Concentration Levels Have Increased to Dangerous Levels[15]

The core argument neo-Brandeisians have relied on to move the Overton window is that lax antitrust enforcement has led to market concentration rising to dangerous levels, and in turn leading to a decline in competition.

Yet, when looked at more closely, the problem is far less serious than the broad pronouncements would suggest. Despite the measured rise in concentration in some industries (at least from 2002 to 2012, the last year of government-provided data), in the vast majority of markets, it remains well below the levels that would normally trigger antitrust concern. Moreover, while concentration has grown in many industries, that growth is usually from very low to low levels. Census data from 2002 and 2012 shows 792 six-digit NAICS (North American Industry Classification System) industries (out of approximately 1,066 total industries) for which a percentage change between the two years could be calculated. Of these, the market share of the top 4 companies either fell or remained constant in 319 industries (40 percent). Another 116 showed an increase of 10 percent or less. Of the 473 industries where concentration increased, the C4 market share remained less than 20 percent in 142 industries and under 40 percent in 281 industries. Only 95 industries saw an increase in concentration that produced a C4 of 60 percent or more (and even at 60 percent, if each firm held an equal market share, this would mean each firm had just 15 percent of the market) and of these, just 45 had increases of more than 10 percentage points.

But there are measurement issues as well. For one thing, most studies often use an inappropriately broad definition of “the market,” and omit the role of imports that reduce concentration. Second, most look only at national concentration levels, when many markets are local in nature. Recent studies conclude that concentration in most local markets has been steady, or even falling. Third, a certain degree of concentration can be good. Rather than leading to a decline in competition, it may result in increased competition in which more productive firms increasingly gain market share over their less-productive and less-innovative rivals.

Finally, the definition of relevant markets for antitrust purposes has continuously been criticized and questioned as being excessively narrow and out of touch with market realities. Indeed, relevant product markets are defined as narrowly as possible to make any company with a certain market power look like a monopolist. Equally, geographically relevant markets are drawn so narrowly that global competition is often overlooked. And potential competition with dynamic entry does not represent a sensible criterion for market definition, contrary to competitive constraints exerted on the market. Consequently, neo-Brandeisians want to narrow the definition of relevant markets to the smallest possible size (only one firm), contrary to academic antitrust literature, which advocates for broader and more-accurate market definitions. Once labeled as a monopolist (akin to Brandeis’s mark of Cain), the resulting backlash and techlash can spread even farther, soon followed by antitrust reforms.[16]

Myth 2: Profits Have Increased to Dangerous Levels Because of Market Concentration[17]

The main evidence neo-Brandeisians use for their case against shifting the Overton window of antirust is the “smoking gun” of higher profits, which they argue is evidence of reduced competition and increased monopoly.

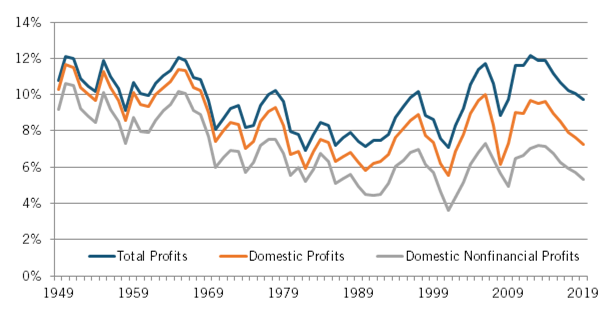

It turns out profits are difficult to accurately measure, especially for determining market power. Some studies do show a rise in profits over the last few decades, but they rely on simplifying assumptions that limit their policy relevance. Moreover, profits as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) are in fact lower than they were in the 1960s, a period of strict antitrust enforcement—and they have been decreasing for the last five years. (See figure 2.) Finally, much of the modest increase in profits in the last two decades has come from foreign profits of U.S. firms (something that is not a U.S. antitrust issue) and profits of the financial services industry. The growth over the last two decades in domestic nonfinancial profits as a share of the economy has in fact been quite modest, suggesting there is actually very little smoke from that gun.

Figure 2: Corporate profits as a percentage of GDP before tax and after inventory and capital[18]

Myth 3: Price Markups Have Increased[19]

In the last few years, a number of academic papers have alleged that price markups (commonly defined as the price of outputs divided by the marginal cost of producing an additional unit) have increased in a large number of industries. They attribute this to increased market concentration giving firms more pricing power.

In reality, the evidence for markups having increased dramatically is extremely weak. The lead study showing large markups also shows markups have increased as much in small firms as in large ones, suggesting market power has nothing to do with the increase. Overall, the evidence suggests that, while markups have increased slightly in some industries, in others they have remained roughly the same. Moreover, if markups have increased as much as the studies claim, then why have domestic, nonfinancial profit rates over the same period increased only minimally?

Markups are notoriously difficult to measure, especially at the firm level. And in most cases, increases appear to be the result of a failure to take into account changes in marginal costs, especially related to the growing share of intangible capital (e.g., R&D and software) in companies, not increases in relative prices.

Myth 4: Market Concentration Has Caused the Number of Start-Ups to Fall[20]

Neo-Brandeisians have argued that market concentration has grown, and that this has caused a precipitous decline in the number of business start-ups. In this narrative, “monopoly” is a sclerotic scourge, robbing the economy of its traditional dynamism—which is largely wrong.

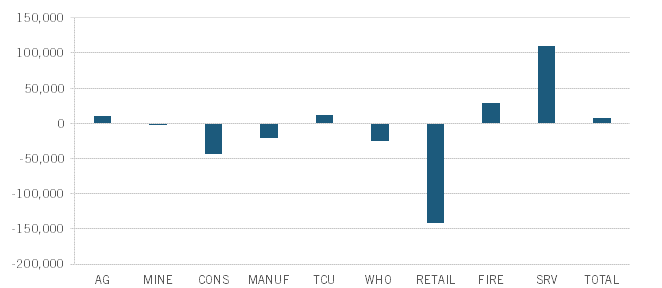

This claim is based on correlation. Concentration has increased while the number of start-ups has fallen; therefore, they argue, concentration caused the decline. In fact, there is no statistical relationship between changes in concentration and changes in new firm formation. Moreover, all the net decline in new firm formation is in one major sector—retail—wherein the results of increasing retail firm size have been superior productivity growth, higher wages for workers in larger stores, and significant consumer benefit in the form of lower prices and broader selection. (See figure 3.)

And when it comes to the most important kind of start-ups—potentially high-growth start-ups, especially in technology sectors—there has been no decline. When MIT professors Jorge Guzman and Scott Stern looked at trends in high-growth entrepreneurship for 15 large states from 1988 to 2014, they found that even after controlling for the size of the U.S. economy, the second-highest rate of high-growth entrepreneurship occurred in 2014.[21]

Figure 3: Change in number of start-ups by major industry, 1977–2016[22]

Myth 5: Superstar Firms Have Gained Market Share by Unfair Means and Harm Economic Welfare[23]

Over the past few decades, many firms have gained market share in their industries, so much so that they have been coined “superstar” firms. This phenomenon has been especially true in digital markets wherein the nation’s largest Internet firms have created the platforms that are fueling rapid growth, but it has also occurred across many industries.

Neo-Brandeisians have latched on to this development to allege that the firms’ growing market share is largely due to anticompetitive conduct, rather than inherently superior business performance. They argue that this market power in turn has allowed firms to raise margins and profits, cut spending on innovation, and unfairly preempt competitive challenges. Even when firms have grown due to superior performance, these advocates warn that the firms often preserve their advantage by adopting a variety of anticompetitive practices.

This market power explanation of superstar firms appears to be flawed. Although some firms have gained even more market share, this has generally not been because the firms used market power to succeed, nor does it suggest reduced economic welfare. Rather, in this environment, a few firms appear to have figured out how to be much more innovative and competitive, and have acted effectively on those insights, enabling them to outperform laggard firms. Indeed, there appears to be something about the nature of current process and product technologies and global market operations that enables some firms to perform better than others, creating more public value in the process. Rather than decry this development and attempt to hold back successful firms, advocates should be celebrating it and identifying ways to help lagging firms do better. If there is a policy problem, it is not due to the success of superstar firms. Instead, it is either the failure of laggards to catch up or some gross mistakes, such as BlackBerry’s persistence on smartphones with keyboards paving the way for Apple and Google’s successes.

Myth 6: Internet Platforms Are Welfare-Reducing Monopolies[24]

Internet platforms are online matchmakers that facilitate commercial agreements between two or more sides of the same market—often buyers and sellers of a particular good or service.[25] They are disruptive precisely because they minimize transaction costs in no comparable way. The rapid growth of large platforms has led neo-Brandeisians to raise the alarm, specifically calling out two issues. First, certain companies, such as Amazon, sell directly to customers but also run a platform that connects third-party suppliers to customers. Neo-Brandeisians claim that such platforms compete unfairly by using third-party sellers’ data about to decide whether to develop and sell competing products.

Second, because of network effects, many platform markets have one or two dominant players, which neo-Brandeisians claim harms consumer welfare and innovation. These concerns are largely misplaced. Platforms create significant economic value. Far from being lazy monopolists that try to increase profits by artificially reducing supply, these companies seek to grow rapidly. They are constantly innovating to both attract new users and retain the ones they have. To do this, they invest enormous amounts of money in R&D.

The welfare-enhancing benefits of platforms often go unnoticed because many services are provided for free. For instance, individuals used to pay for pricey GPS equipment and mapping subscription services—but only rarely. Now, everyone has free GPS and mapping services in their smartphone. The benefits here—not lower choice but greater choice, not higher prices but lower prices, not lower innovation but disruptively thriving innovation—can hardly be measured, as individuals now have free access to services they would have never paid for previously.

While the potential benefits of the platform business model are great, the dangers are overdone. These platforms face continued competition in many of the markets they participate in, competing for “eyeballs” with both each other and other forms of media. Their industries are continually evolving. Although some compete with other companies on their platforms, the incentive to attract more third-party suppliers usually outweighs their interest in displacing any one supplier.

Myth 7: Market Concentration Has Caused Labor’s Share of Income to Fall[26]

Neo-Brandeisians have argued that increased market concentration has reduced the share of national income going to labor. The idea is that as companies gain more market power, they take an increased share of economic output, with workers getting less.

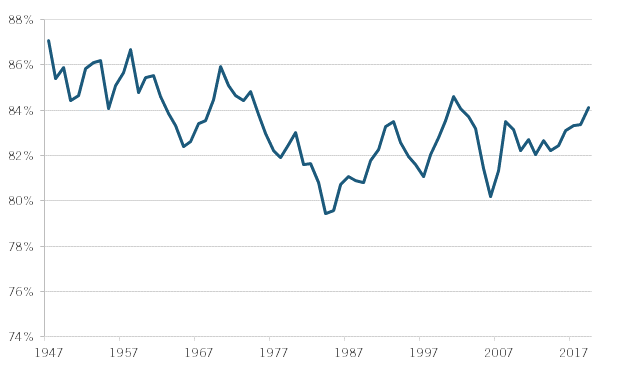

But according to the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, virtually none of labor’s lost share of income goes to increased profits, as a theory of market power might predict. Rather, the gains are almost totally from increases in both rental income—imputed rent (the value an owner would get from renting the home they occupy at market rates) homeowners receive and actual rent renters pay—and to some extent the mismeasurement of self-employment income. And when looking at the change in combined worker, rental, and self-employment income as a share of net national income, versus combined profits and net interest income, the former ratio is essentially unchanged over the last 90 years. (See figure 4.) In other words, the declining share of labor income has almost nothing do with monopoly power.

Figure 4: Total employee compensation, rental income, and proprietors’ income as a share of net domestic income (1947–2019)[27]

Myth 8: Big Technology Companies Create Innovation Kill Zones[28]

Large U.S. technology platforms invest almost as much in R&D as the entire U.K. economy does (business and government).[29] But knowing that innovation is important, neo-Brandeisians have argued that big technology companies actually limit innovation, either by acquiring start-ups in order to terminate the development of innovations that threaten their continued dominance (“killer acquisitions”) or by creating areas of the market in which they exert dominance to the extent others won’t invest in them (“kill zones”). Either way, large tech companies supposedly limit prospective challengers from being able to take root and grow, thereby limiting not only competition but overall U.S. innovation.

In fact, acquisitions may be beneficial, at least to innovation, if they allow the larger firms to benefit from economies of scale or network effects, and enable the smaller firms to reach many more customers much more quickly with a higher quality product. Moreover, the prospect of being purchased by a larger company often motivates founders and venture capitalists to invest. Making it more difficult for them to sell therefore might make it harder for promising firms to find funding.

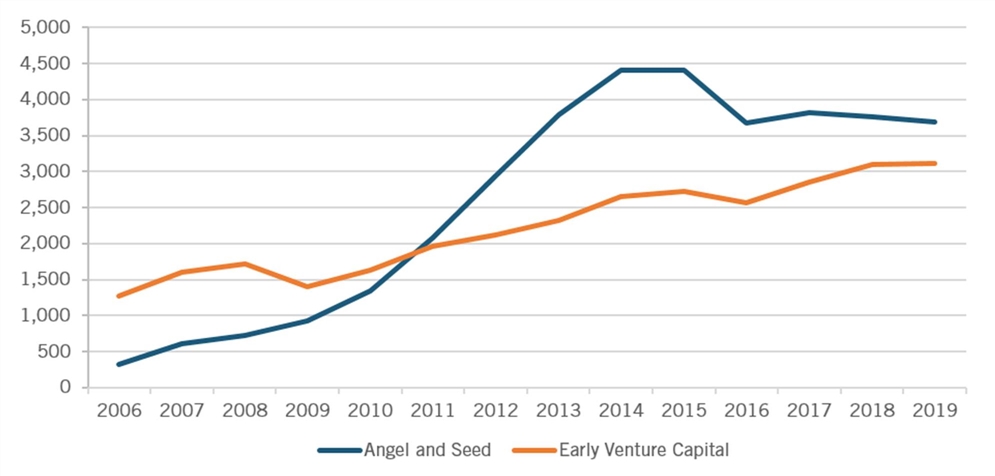

And rather than looking at so-called kill zones as an innovation deterrent, it is more accurate to view them as an innovation enabler that guides entrepreneurial resources (talent and capital) to areas that have the best chance of success. Why invest in companies seeking to duplicate mature products offered by large firms that benefit from economies of scale or network effects? It is better for society if new companies concentrate instead on other markets they can break into. Indeed, that seems to be occurring, as venture capital investment, especially in early-stage deals, has grown significantly over the last decade, indicating that there is no shortage of innovation opportunities.

Moreover, if they are creating kill zones, why did the number of angel and seed deals rise almost sixfold between 2006 and 2019, peaking in 2015? The number of early deals rose by 2.4 times. It is hard to see any sign of investor activity slowing down. (See figure 5.)

Figure 5: U.S. equity investment deal volume in the information technology sector (2006–2019) [30]

Conclusion

Getting antitrust right—which means focusing on the consumer welfare and innovation incentives, not presuming that large firms are bad, and focusing more on policing anticompetitive conduct than on structural remedies—is critical to ensuring U.S. economic growth and competitiveness.

While the current antitrust system can always be improved, such as increasing funding for enforcement agencies, any attempt to shift the Overton window away from the current system to the neo-Brandeisian one would likely mean a reduction of U.S. innovation and growth.

Getting antitrust right is critical to ensuring U.S. economic growth and competitiveness.

It is crucial that case-by-case analysis—wherein economic arguments are balanced out in order to avoid both false positives and false negatives—remains the fundamental standard of antitrust analysis. Antitrust liability can, and must be, engaged whenever anticompetitive conduct is duly evidenced and the costs are greater than the expected gains from such practice. Absent this necessary evidence, it is the rule of law, the Supreme Court’s ability to review administrative decisions, and the rise of discretionary power that are at stake—and could be jettisoned.

This is not to say that antitrust enforcement should not be altered for substantiated reasons different from those unconvincingly invoked by neo-Brandeisians. However, current antitrust laws can accommodate a change of decisional practice. Indeed, as the economic constitution of the nation, the Sherman Act is adaptable to contemporary antitrust matters. Antitrust enforcement can be changed without altering antitrust laws. First, through courts’ practice—akin to the common law—the evolution of antitrust jurisprudence improves the knowledge accrued from decisional practice. Second, DOJ and the Federal Trade Commission’s joint guidelines can powerfully alter the course of antitrust decisional practice. Finally, through administrative enforcement, recent lawsuits have demonstrated that antitrust enforcers can use current antitrust laws to trigger desired outcomes.

Consequently, there is no convincing case for a change of antitrust laws since adaptation to new market realities has been inherent to the practice of the Sherman Act. But neo-Brandeisians know this, which is why they work so hard to perpetuate myths, define many markets as monopolies, and call for a new “public interest” standard. Before policymakers go down such a transformative path, they should stop and carefully assess the evidence behind the neo-Brandeisian case.

About the Author

Robert D. Atkinson (@RobAtkinsonITIF) is the founder and president of ITIF. Atkinson’s books include Big Is Beautiful: Debunking the Myth of Small Business (MIT, 2018), Innovation Economics: The Race for Global Advantage (Yale, 2012), Supply-Side Follies: Why Conservative Economics Fails, Liberal Economics Falters, and Innovation Economics is the Answer (Rowman Littlefield, 2007), and The Past and Future of America’s Economy: Long Waves of Innovation That Power Cycles of Growth (Edward Elgar, 2005). Atkinson holds a Ph.D. in city and regional planning from the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

About ITIF

The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) is an independent, nonprofit, nonpartisan research and educational institute focusing on the intersection of technological innovation and public policy. Recognized by its peers in the think tank community as the global center of excellence for science and technology policy, ITIF’s mission is to formulate and promote policy solutions that accelerate innovation and boost productivity to spur growth, opportunity, and progress.

For more information, visit us at www.itif.org.

Endnotes

[1]. Nathan J. Russell, “An Introduction to the Overton Window of Political Possibilities” (Mackinac Center for Public Policy, January 2006), https://www.mackinac.org/7504.

[2]. U.S. v. Trans-Missouri Freight Association, 166 U.S. 290 (1897), where the Court considered that even if lower prices result from a merger, “[t]rade or commerce … may nevertheless be badly and unfortunately restrained by driving out of business the small dealers and worthy men whose lives have been spent therein.”

[3]. Robert Reich, “Why We Must End Upward Pre-distributions to the Rich,” blog post, RobertReich.org, September 25, 2015, http://robertreich.org/post/129996780230.

[4]. Nell Abernathy, Mike Konczal, and Kathryn Milani, “Untamed: How to Check Corporate, Financial, and Monopoly Power” (New York: Roosevelt Institute, June 2016), http://rooseveltinstitute.org/untamed-how-check-corporate-financial-and-monopoly-power/.

[5]. Department of Justice, “Justice Department Sues Monopolist Google For Violating Antitrust Laws,” October 20, 2020, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-sues-monopolist-google-violating-antitrust-laws; Federal Trade Commission, “FTC Sues Facebook for Illegal Monopolization,” December 9, 2020, https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2020/12/ftc-sues-facebook-illegal-monopolization.

[6]. Lina Khan, “New Tools to Promote Competition,” Democracy Journal 42 (Fall 2016).

[7]. Robert D. Atkinson, “Big Business Is Not the Enemy of the People,” National Review, October 10, 2019, https://www.nationalreview.com/magazine/2019/10/28/big-business-is-not-the-enemy-of-the-people/.

[8]. Glenn G. Lammi, “Transformation Of Antitrust Law To All-Purpose Cure For Socioeconomic Ills Would Backfire,” Forbes, July 23, 2019, https://www.forbes.com/sites/wlf/2019/07/23/transformation-of-antitrust-law-to-all-purpose-cure-for-socio-economic-ills-would-backfire/?sh=5697945974a8.

[9]. Sandeep Vaheesan, “How Antitrust Perpetuates Structural Racism,” The Appeal, September 16, 2020, https://theappeal.org/how-antitrust-perpetuates-structural-racism/; Neil Chilson and Casey Mattox, “[The] Breakup Speech: Can Antitrust Fix the Relationship Between Platforms and Free Speech Values?” Knight First Amendment Institute, March 5, 2020, https://knightcolumbia.org/content/the-breakup-speech-can-antitrust-fix-the-relationship-between-platforms-and-free-speech-values; Maurice E. Stucke, “Should Competition Policy Promote Happiness?” Fordham Law Review, vol. 81 issue 5 (2013): 2575–2645, https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol81/iss5/14/.

[10]. Robert D. Atkinson and Michael Lind, Big is Beautiful: Debunking the Mythology of Small Business (MIT Press, 2018).

[11]. K. Sabeel Rahman, “Curbing the New Corporate Power,” Boston Review, May 4, 2015, http://bostonreview.net/forum/k-sabeel-rahman-curbing-new-corporate-power.

[13]. Chase Johnson, “Big tech surveillance could damage democracy,” The Conversation, June 3, 2019, https://theconversation.com/big-tech-surveillance-could-damage-democracy-115684; Ganesh Sitaraman, “The National Security Case for Breaking Up Big Tech,” Knight First Amendment Institute, January 30, 2020, https://knightcolumbia.org/content/the-national-security-case-for-breaking-up-big-tech.

[14]. “Monopoly Myth Series,” ITIF, accessed March 2, 2021, https://itif.org/monopoly-myth-series.

[15]. Joe Kennedy, “Monopoly Myths: Are Markets Becoming More Concentrated?” (ITIF, June 2020), https://itif.org/publications/2020/06/29/monopoly-myths-are-markets-becoming-more-concentrated.

[16]. Aurelien Portuese and Joshua D. Wright, “Antitrust Populism: Towards a Taxonomy,” Stanford Journal of Law, Business, and Finance 21, (2020): 1–49, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3400274.

[17]. Joe Kennedy, “Monopoly Myths: Is Concentration Leading to Higher Profits?” (ITIF, May 2020), https://itif.org/publications/2020/05/18/monopoly-myths-concentration-leading-higher-profits.

[18]. Joe Kennedy, “Concentration is Not Producing Higher Profits or Markups,” Competition Policy International, November 22, 2020, https://www.competitionpolicyinternational.com/concentration-is-not-producing-higher-profits-or-markups/.

[19]. Joe Kennedy, “Monopoly Myths: Is Concentration Leading to Higher Markups?” (ITIF, June 2020), https://itif.org/publications/2020/06/01/monopoly-myths-concentration-leading-higher-markups.

[20]. Robert D. Atkinson and Caleb Foote, “Monopoly Myths: Is Concentration Leading to Fewer Start-Ups?” (ITIF, August 2020), https://itif.org/publications/2020/08/03/monopoly-myths-concentration-leading-fewer-start-ups.

[21]. Jorge Guzman and Scott Stern, “The State of American Entrepreneurship: New Estimates on the Quantity and Quality of Entrepreneurship for 15 US States, 1988–2014,” NBER Working Paper No. 22095 (Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, March 2016), http://www.nber.org/papers/w22095.

[22]. Figure codes: AG = agriculture; MINE = mining; CONS = construction; MAN = manufacturing; TCU = transportation, communications, and utilities; WHO = wholesale trade; FIRE = finance, insurance, and real estate; and SRV = services. The sum of numbers from each major sector does not equal the overall economic change number because of changes in industry classification codes over this period—some start-ups are not assigned an industry code. Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Longitudinal Business Database 1977–2016 (Change in number of new establishments; accessed March 2, 2021), https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/ces/data/restricted-use-data/longitudinal-business-database.html.

[23]. Joe Kennedy, “Monopoly Myths: Are Superstar Firms Stifling Competition or Just Beating It?” (ITIF, January 2021), https://itif.org/publications/2021/01/11/monopoly-myths-are-superstar-firms-stifling-competition-or-just-beating-it.

[24]. Joe Kennedy, “Monopoly Myths: Do Internet Platforms Threaten Competition?” (ITIF, July 2020), https://itif.org/publications/2020/07/23/monopoly-myths-do-internet-platforms-threaten-competition.

[25]. “ITIF Technology Explainer: What are Digital Platforms?” (ITIF, October 2018), https://itif.org/publications/2018/10/12/itif-technology-explainer-what-are-digital-platforms.

[26]. Joe Kennedy, “Monopoly Myths: Is Concentration Eroding Labor’s Share of National Income?” (ITIF, October 2020), https://itif.org/publications/2020/10/13/monopoly-myths-concentration-eroding-labors-share-national-income.

[27]. U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, National Income and Product Accounts, Table 1.10 (accessed March 2, 2021), https://apps.bea.gov/iTable/iTable.cfm?reqid=19&step=2#reqid=19&step=2&isuri=1&1921=survey. Net domestic income is equal to gross domestic income minus consumption of capital and taxes on production and imports. These calculations include all of proprietors’ income. However, Elsby, Hobijn, and Şahin showed that almost all of this category should be attributed to labor income. Michael W.L. Elsby, Bart Hobijn and Ayşegűl Şahin, “The Decline of the U.S. Labor Share,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity (Fall 2013), https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/2013b_elsby_labor_share.pdf.

[28]. Joe Kennedy, “Monopoly Myths: Is Big Tech Creating ‘Kill Zones’?” (ITIF, November 2020), https://itif.org/publications/2020/11/09/monopoly-myths-big-tech-creating-kill-zones.

[29]. European Commission, EU R&D Scoreboard, 2020, http://iri.jrc.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2020-04/EU%20RD%20Scoreboard%202019%20FINAL%20online.pdf; Gross domestic expenditure on research and development, U.K. - Office for National Statistics (ons.gov.uk).

[30]. Ibid.