EU Hypocrisy on Digital Trade

Europe has responded to America’s digital leadership with concern, even alarm. Many EU policymakers call out U.S. technology “colonization” and call for “digital sovereignty” against (U.S.) “dominant platforms.” The French minister for economic affairs went so far as to call U.S. “big tech” companies as an “adversary of the state.”

The EU now is convinced that it needs to, in the words of EU President Ursula von der Leyen “achieve technological sovereignty in some critical technology areas.” Thierry Breton, the EU commissioner for internal market, argues that “European data should be stored and processed in Europe because they belong in Europe.” And the proposed EU Digital Services Act is quite clear of the intent: “Asymmetric rules will ensure that smaller emerging competitors are boosted, helping competitiveness, innovation and investment in digital services...”

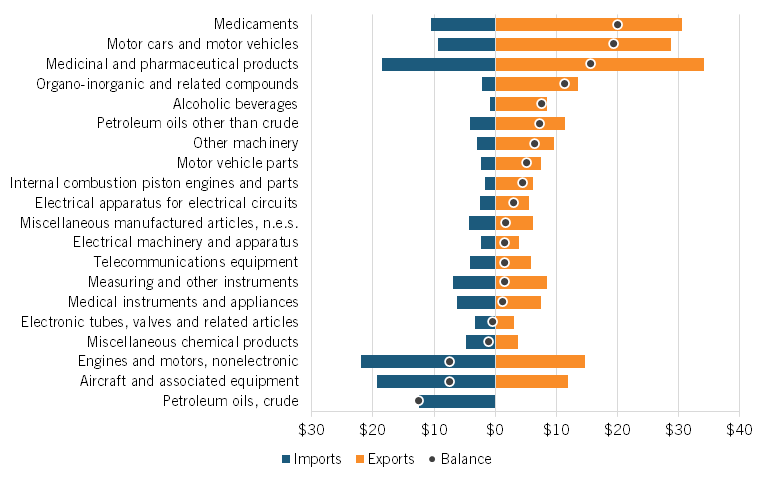

Listening to these protestations, one might be excused for thinking the EU must be running massive trade deficits with the United States that are hollowing out their economy. The reality is completely the opposite. In 2019 the EU ran a trade surplus of $130.4 billion with the United States. As seen in figure 1, the EU runs significant trade surpluses with the United States on pharmaceuticals and medical devices, motor vehicles and parts, chemicals, electrical goods, and instruments.

Figure 1: EU trade balance with the United States in goods industries, 2019 ($billions)

Of the 27 EU nations, all but 5 (Malta, Cyprus, Luxemburg, Belgium, and Netherlands) ran trade surpluses in goods with the United States. And the two countries with officials who complain the loudest of U.S. “digital dominance”—Germany and France—run the first and fourth largest trade deficits.

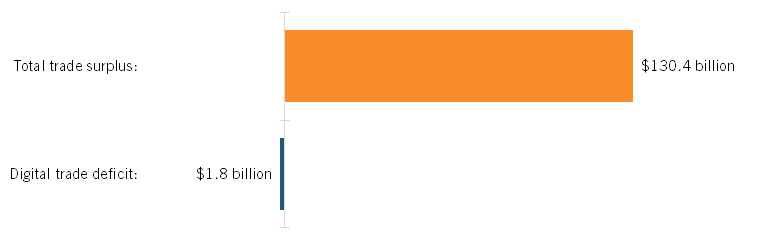

But doesn’t the U.S. dominate in digital industries, like cloud computing and information services (like search engines and social media)? In fact, the U.S. trade surplus with the EU is miniscule compared to the overall trade deficit. In 2019, the United States had a positive trade balance of $861 million in cloud computing, $883 million in database and information services, and $56 million in telecommunication services, for a total surplus of $1.8 billion. As figure 2 shows, the trade deficit in information is dwarfed by the overall trade surplus. In fact, the U.S. trade surplus in the three digital sectors is just 1.4 percent of the EU trade surplus overall.

Figure 2: EU trade balance with the United States, 2019

This matters because this EU narrative of dominance of dependency is used to justify soft digital protectionism by the EU, including aggressive antitrust enforcement with massive fines, mandated data sharing, digital services taxes, discriminatory regulation focused on big U.S. firms, and other measures, coupled with subsidies, preferences for national champions, and other favors for EU tech and digital firms.

Ironically, as the EU goes down the path of digital protectionism, it runs counter to messages from DG Trade, which states, “Trade allows countries to procure the best products and services for its citizens internationally. This means government and local authorities can spend less public money on the products and services they purchase” and “Trade makes it easier to exchange innovative or high-technology products.” Clearly Europe is talking out of both sides of its mouth—promoting free trade so it can get access to foreign markets for its goods, but also protecting its markets when it comes to some sectors and technologies where it is weaker.

The EU and the United States should come to an agreement: Both nations will agree that the EU can engage in protectionist digital industrial policies only when and if the ratio between the trade deficit in IT/services is at least 10 percent the trade deficit in goods. (It is now 1.4 percent.) Until then, the United States gets to sell into the EU market without protectionist and industrial policy measures.