Pew Survey Offers Further Evidence of the Privacy Panic Cycle

The Pew Research Center released a survey last week that investigated the circumstances under which many U.S. citizens would share their personal information in return for getting something of perceived value. In the survey, Pew set up six hypothetical scenarios about different technologies—including office surveillance cameras, health data, retail loyalty cards, auto insurance, social media, and smart thermostats—and asked respondents whether the tradeoff they were offered for sharing their personal information was acceptable.

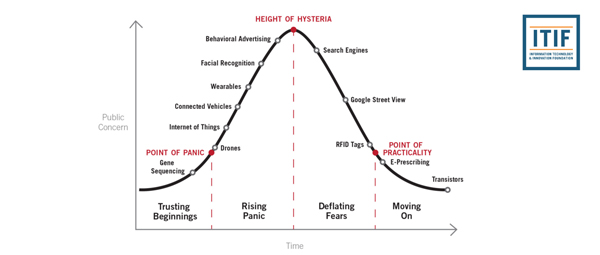

To be sure, some of the questions that Pew asked described one-sided tradeoffs that could have tainted the findings. Nevertheless, the overall results reveal that the Privacy Panic Cycle, the usual trajectory of public fear followed by widespread acceptance that often accompanies new technologies, is still going strong for many technologies.

The Privacy Panic Cycle explains how privacy concerns about new technologies flare up in the early years, but over time as people use, understand, and grow accustomed to these technologies, the concerns recede. For example, when the first portable Kodak camera first came out, it caused a big privacy panic, but today most people carry around phones in their pockets and do not give it a second thought.

So what does Pew’s recent survey reveal?

The survey shows that the technologies that have been around the longest and are most familiar to consumers (e.g., workplace cameras, electronic health records, and retail loyalty cards) are the most acceptable to the average consumers, while the newer technologies (e.g., smart thermostats, in-vehicle monitoring for insurance, and a hypothetical “new social media platform”) are the least acceptable. We should expect that if Pew repeated this survey in a few years, the privacy concerns of these newer technologies would decline as consumers become more familiar with them and other, newer technologies would take their place as most feared.

Indeed, privacy concerns about some of the older technologies follow the expected trajectory. To be sure, while comparisons between surveys using different methodology are not apples-to-apples comparisons, they can still reveal some trends.

With regard to office surveillance cameras, privacy concerns for employee monitoring have decreased over time. In fact, Pew’s survey found that a majority of American’s think it is acceptable for employers to install cameras to monitor employees for workplace theft, by a 54 percent to 24 percent margin. By contrast, another study from 2005 found that only 15 percent agreed with employers using a camera to monitor their employees for theft and 43 percent disagreed. (It is important to note that the methodology of these surveys was different.)

Consumer concerns towards retail loyalty card programs have also diminished over time. Throughout the early 2000s, privacy advocates made these programs one of the primary targets of their disdain. Not surprisingly, a 2004 survey found that 52 percent of Americans worried about how much information supermarkets collected. And yet, in 2016 when Pew asked if Americans are willing to use loyalty cards in exchange for saving money on purchases, only 32 percent of respondents found the exchange unacceptable. Again, this shows a change predicted by the Privacy Panic Cycle.

Pew’s research suggests that the Privacy Panic Cycle will likely continue to distort perceptions about new technologies for the foreseeable future. Therefore, policymakers should be careful not to take the wrong message from these surveys. These surveys are not showing that consumers are unwilling to adopt new technologies or that privacy concerns necessitate new regulations, but rather that consumer acceptance of new technology simply takes time.

Daniel Castro contributed to this article.

Editors’ Recommendations

December 18, 2015

EFF Accelerates the Privacy Panic Cycle for EdTech

September 10, 2015

The Privacy Panic Cycle: A Guide to Public Fears About New Technologies

October 2, 2015