It’s Global Warming, Not Just American Warming

One of the chief takeaways from the Energy Innovation 2013 conference last week is that “it’s global warming, not just ‘American warming,” as ITIF president Robert Atkinson put it in his opening remarks. “To fight climate change, policymakers need more than existing methods at their disposal and they must target clean technology innovations globally, according to experts,” is how E&E News summarized (subscription article) the event, with the emphasis on “globally.” It is thus unsurprising that economist Noah Smith wrote a thoughtful blog post that reaches the same conclusion.

Smith starts out by highlighting an infographic from the Business Council for Sustainable Energy which notes that U.S. total energy-related carbon emissions are down 13% since 2007, with natural gas increasingly providing baseload power in lieu of coal. “If the U.S. were the world,” Smith observes, “the fight against global warming would be going well.” Of course, “the U.S. is not the world”:

Global warming is global. The only thing that matters for the world is global emissions. And global emissions are still going up, thanks to strong increases in emissions in the developing world, notably China.

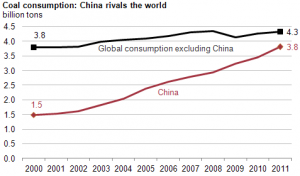

Figures released this week show skyrocketing Chinese coal use. China now burns almost as much coal as the rest of the world combined:

[Image credit: U.S. Energy Information Administration].

Meanwhile, Indian coal use is also increasing strongly.

If China and the other developing nations cook the world, the world is cooked, no matter what America or any other country does. China et al. can probably cook the world without our help, because global warming has "threshold effects" (tipping points), and because carbon stays in the air for thousands of years.

Bottom line: We will only save the planet if China (and other developing countries) stop burning so much coal. Any policy action we take to avert global warming will be ineffective unless it accomplishes this task.

Smith is absolutely right on this point. “China in particular,” he notes, “is not a very globally responsible country; it will continue to pursue growth, economic size, and geopolitical power at any cost, and that means using the cheapest energy source available. The only way China will stop using coal is if it becomes un-economical to continue using coal.” Similar reasoning applies to India – where as many as 300 million people, or 25% of the population, do not yet have regular access to electricity – as well as the rest of the developing world seeking to rise from energy poverty.

“As I see it,” Smith concludes, “there is only one thing we can do: develop renewable technologies that are substantially cheaper than coal, and give these technologies to the developing countries.” Here’s where Smith veers off the beaten path a little – innovating better clean technologies is clearly necessary, but giving them away is not. Natural technology diffusion through the global market should be sufficient to achieve widespread adoption, especially if clean technologies become genuinely cost and performance competitive without having to rely on subsidies – clean tech will sell itself. Furthermore, the responsibility for clean energy innovation does not have to fall on the U.S. and developed world alone. As ITIF has assiduously detailed, there is much the U.S. can do to combat and discourage green mercantilism and turn countries like China towards more innovation-focused energy policy agendas.

Unfortunately, the world as a whole is not doing a good job of prioritizing energy innovation. Bloomberg New Energy Finance reports that global clean energy investment in 2012 was close to $270 billion (down more than $30 billion from 2011), but only a small piece of that, $30.2 billion, was spent on public and private investment in research and development. Furthermore, it’s unclear how much global investment was allocated to other pieces of the innovation puzzle like demonstration projects and smart procurement for emerging clean technologies. Thus, in the United States, it is more important than ever that energy stakeholders ask themselves in the context of crafting policy, as Atkinson stated in his closing remarks at Energy Innovation 2013, “How does it get us to globally deployed, zero emissions technologies? Will this solve more than American warming?”