Bank Privacy Notices Cost Consumers Over $700M Annually

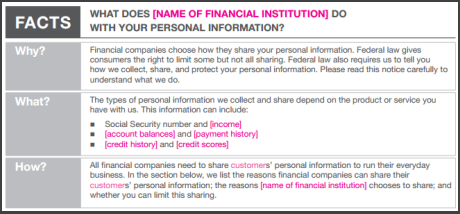

The Gramm-Leach-Bliley Financial Modernization Act of 1999 requires that financial institutions provide privacy notices to consumers at least once a year (or sooner if the privacy policy changes). Since this provision went into effect in July 2001 people tend to receive these notices in the summer. Yet when was the last time you read the privacy policy of your bank? For most people, the answer is probably “never.” Consumers generally don’t like reading fine print and often find it confusing. (Although to address the complexity issue, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) created a Model Privacy Form for banks to use to communicate privacy information more effectively to their customers.) Yet regardless of the apparent apathy of most customers towards the privacy policies of their financial institution, banks dutifully send out these notices every year as required by law.

The Gramm-Leach-Bliley privacy notices illustrate how misguided privacy regulations tend to be in the United States. Rather than provide any actual benefit to consumer privacy, they just serve to raise costs. And the costs of all of these privacy notices add up. According to a 2009 report from the FDIC, approximately 7.7 percent of U.S. households are unbanked. This means that there are approximately 122 million households in the United States with at least one bank account. In addition, the Census Bureau estimates that 1.3 billion credit cards have been issued in the United States (most people have more than one credit card). If we conservatively estimate that the cost of printing and mailing these privacy notices is approximately $0.50 a statement, this means that the Gramm-Leach-Bliley privacy notices cost financial institutions over $700 million annually. And this estimate doesn’t count the numerous privacy notices sent out by insurance companies, mortgage companies or other financial institutions that fall under the purview of Gramm-Leach-Bliley.

There is also the environmental cost of sending out these statements. The environmental calculator at PayItGreen.org provides a way to estimate the cost of paper statements. Using the numbers above, my estimate shows that if these privacy notices were eliminated, we would:

- save nearly 40 million pounds of paper

- avoid creating 442 million gallons of wastewater

- avoid using 3.1 million gallons of gasoline to mail statements

- prevent producing 171 million pounds of greenhouse gases

In response to this waste, Rep. Luetkemeyer (R-MO) has introduced H.R. 5817, the Eliminate Privacy Notice Confusion Act. This bill would provide an exemption to financial institutions from sending the annual privacy notice if they do not share information with affiliates and have not changed their privacy policy since their last notice. In addition, financial institutions would not have to provide any privacy notice to consumers in states that require opt-in for sharing customer data.

This is a good start, but it could go further. I have argued before that government policy should “nudge digital” to promote more-efficient choices, such as by making electronic statements the default option. The Social Security Administration recently adopted this policy when it eliminated the annual mailing of Social Security statements to all workers over the age of 25. The Social Security Administration Commissioner Michael Astrue estimated that by eliminating these statements the government would save approximately $70 million in printing and mailing costs. Instead, individuals can now access these statements online.

A better approach would be to eliminate the printed Gramm-Leach-Bliley privacy notices altogether and only require that banks send this information to customers who have a registered email address. This would be keeping in line with a general trend towards more use of online banking. A survey in 2009 by Fiserv estimated that 80 percent of households with Internet access use online banking services. Similarly a 2012 Pew Internet and American Life Project survey shows that 61 percent of adult Internet users use online banking. Most banks already offer e-statements and have implemented various incentives to get customers to adopt paperless statements, such as by waiving certain account fees or providing other bonuses. For example, Washington Mutual donated one dollar to the National Arbor Day Foundation for every customer that switched to an e-statement during its 2008 “Make a Statement, Plant A Tree” campaign. Some banks have gone the other route and have imposed a monthly fee on customers who choose to receive paper statements. Similarly, banks should be able to charge a fee to send privacy notices to customers in the mail. If a bank wants to offer the option, customers that want to receive these privacy notifications by mail should be able to choose to do so, but banks should recoup the associated cost directly from these customers.

Of course, the debate about privacy notices is ancillary to the one about how consumer financial data is actually used. Most consumers cannot opt out of having banks share their personal information with certain third-parties, such as a service provider working for the bank, affiliates of the bank (e.g. if a bank and a mortgage company are owned by the same parent company), and other companies that the bank has joint marketing agreements with. Most consumers do have the option to opt out of having their data shared by their financial institutions with other third-parties; however some states, like California, require consumers to opt in to data sharing. This means that the average consumers who have not opted-out of data sharing from their bank or credit card, and are receiving advertisements based on their financial information from a non-affiliated third-party, are effectively “paying” for the privacy of Californian residents.

These policies should not vary from state to state. Since creating a new account is a relatively rare occurrence, financial institutions should require consumers to decide whether or not they want to allow their financial information to be shared when they create an account. To that end, Congress should require all financial institutions to obtain this information for new accounts, rather than allowing each state to set its own rules. There does not need to be an “opt in” or an “opt out”—there just needs to be a mandatory choice. Financial institutions should also be allowed to offer incentives to those who opt to share their data or charge fees to those who opt not to share. This way the costs and benefits of sharing data are better aligned for all consumers.

Editors’ Recommendations

January 12, 2015

Barack Obama Presses Privacy, Data Breach Agenda Post-Sony

December 26, 2014

Who Governs the Online World?

December 19, 2014