Stricter Privacy Regulations for Online Advertising Will Harm the Free Internet

A study shows that overly strict privacy laws inhibit the effectiveness of the Internet ecosystem.

Privacy legislation under consideration could reduce the effectiveness of online advertising and thus reduce the available revenue to support free or low-cost content, applications and services. Before passing such legislation, policymakers should review the empirical data on the importance of online advertising, the effectiveness of targeted ads, and the impact of regulations on online advertising. They should be aware that data privacy regulations could sharply limit the principal funding mechanism for most of the free Internet enjoyed by consumers today and result in lost jobs, investment and Internet innovation.

It is surprising that policymakers would want to tamper with one of the most successful drivers of economic activity in the United States as the national economy struggles to rebound from a recession. Let’s be clear—the Internet is a critical component of the economy both globally and domestically. ITIF estimates that the annual global economic benefits of the commercial Internet equal $1.5 trillion, more than the global sales of medicine, investment in renewable energy, and government investment in R&D, combined.[1] Moreover, the Internet has a substantial impact on the U.S. economy. A 2009 study co-authored by the Hamilton Consultants and Harvard Business School professors John Deighton and John Quelch found that in the United States the Internet generates at least $300 billion of economic activity annually, or approximately 2 percent of the U.S. GDP.[2] And while the U.S. has lost leadership and jobs in an array of industries, it still leads the world—by a considerable margin—in the Internet industry.

The Internet is important to our economy and online advertising is the dynamo powering the Internet’s rapid growth. Many of the websites that millions of Americans depend on for work and play would not be around today without online advertising. In fact, the top five websites in the United States—Google, Facebook, Yahoo, YouTube and Amazon.com—all use online advertising to support their products and services.

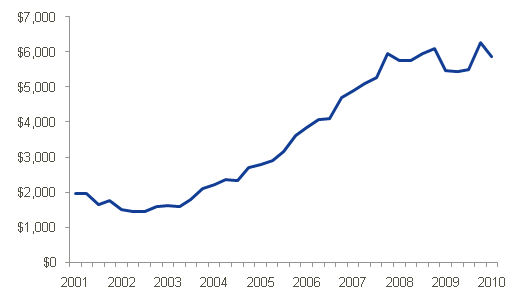

As shown in Figure 1, Internet advertising has grown dramatically over the past decade. In the United States, non-search online advertising expenditures have grown from $6 billion in 2002 to $13 billion in 2007. Similarly paid search has grown from $1 billion in 2002 to $8 billion in 2007.[3] The Internet Advertising Bureau estimated cumulative Internet online advertising market to be $21.1 billion as of 2007. The Kelsey Group found that worldwide Internet advertising reached approximately $45 billion in 2007, out of a total $600 billion advertising market, and predicts online advertising will grow to over $147 billion by 2012.[4] IDC reports similar figures estimating that worldwide spending on Internet advertising reached $61 billion in 2009. In addition, IDC predicts that advertisers will increasingly use the Internet for advertising, with online ad spending growing from 10 percent of all ad spending in 2009 to almost 15 percent by 2013.[5]

Figure 1: U.S. Quarterly Internet Ad Revenue since 2001, Source: IAB/PWC[6]

Internet advertising supports the creation of new content, applications and services. A case in point is the newspaper industry. Policymakers concerned with the decline of print media should note that greater revenue from targeted online advertising will likely be necessary for journalism to survive in the Internet age.[7] We are already seeing some evidence of this. For example, the Los Angeles Times announced in 2009 that its online advertising revenue was sufficient to cover its entire editorial payroll.[8] And online advertising will be important for the so-called “long tail” of small websites and content producers supported by ad revenues. After Google introduced a revenue-sharing program in 2007 for YouTube, various Internet entrepreneurs began turning their videos into a lucrative business. For example, Josh Chomik, a teenager in New Jersey earns around $1,000 a month from ad revenue generated by his YouTube videos.[9]

If online advertising is important to the Internet ecosystem today then ensuring that online advertising revenues continue to grow will be central to the Internet’s growth and success tomorrow. One way websites gain more value from online advertising is by providing more relevant ads—a benefit both to consumers who get more utility from these ads and advertisers who are willing to pay more to reach their target audience. Targeted ads based on information about a user—such as the user’s browsing history or other user-specific data—help deliver higher-value ads. Yet even though the importance of online advertising to the greater Internet economy has been well-documented, policymakers seem intent on imposing data privacy regulations that would limit the ability of Internet publishers to tailor advertising to users based on their interests.

Part of this may be due to a misconception about how targeted advertising works. When Google offered ads to its Gmail users based on contextual information in emails, privacy advocates objected to Google “reading people’s email.”[10] Yet these claims do not distinguish between ads delivered to web users through automated computer technology and an individual snooping through personal emails. In the former, providing targeted computer-matched ads poses no more privacy threat to users than simply having their emails stored on remote servers. Similarly privacy concerns have been raised about Facebook with fictional claims of the company selling its user’s data because of misunderstanding about the mechanisms of targeted advertising. Targeted advertising works by matching ads to users based on the information in their profile. For example, a wedding photographer in Dallas can pay Facebook to serve an ad to everyone in Dallas who switches their relationship from “single” to “engaged.” This benefits everyone—the photographer gets more clients, the users get more relevant ads, and Facebook is better able to fund its free services. And at no time does the photographer learn who sees the ads, unless a user chooses to make contact.

These benefits from targeted advertising are clearly documented. Howard Beales, a professor in the School of Business at George Washington University and former Director of the Bureau of Consumer Protection at the Federal Trade Commission, has described how targeted advertising leads to higher value for Internet publishers and consumers. In 2009, Beales authored a report which found that advertising rates for online ads that used behavioral targeting were significantly higher than online advertising that did not use behavioral targeting (2.68 times as much).[11] Moreover, targeted ads are more relevant to consumers. This fact is supported by the data—click-through-ratios, or the percent of web users that click on an ad, for targeted ads are as much as 670 percent higher than non-targeted ads.[12] Beales looks at conversion rates—or the percent of online advertisements that turn into sales—and finds that the conversion rate for ads using behavioral targeting is twice that of ads not using it.

Now a new research paper by Avi Goldfarb at the University of Toronto and Catherine Tucker from MIT takes this research a step further and documents how privacy laws can negatively impact the efficacy of online advertising.[13] Specifically Goldfarb and Tucker analyzed the impact of the European Union’s Privacy and Electronic Communications Directive (2002/58/EC) which was implemented in various European countries and limits the ability of advertisers to collect and use information about consumers for targeted advertising. The authors find that after the new privacy laws went into effect they resulted in an average reduction in the effectiveness of the online ads by approximately 65 percent (where the effectiveness being measured is the frequency of changing consumers’ stated purchase intent). The authors write “the empirical findings of this paper suggest that even moderate privacy regulation does reduce the effectiveness of online advertising, that these costs are not borne equally by all websites, and that the costs should be weighed against the benefits to consumers.”

All of these analyses support the larger conclusion that targeted advertising is crucial for supporting the websites responsible for the majority of the free and low-cost content online. This is particularly true for general-interest sites (like news websites) that have little ability to determine what ads their users would be most interested in without the cues that better targeting enables (in contrast to some special-interest sites which can do so somewhat more easily). Not surprisingly, Goldfarb and Tucker found that the negative impact on ad effectiveness from the European privacy regulations was strongest among these sites. The negative impact was also stronger for non-obtrusive ads (e.g. smaller ads or ads not using multimedia) which suggests that small, text ads will be significantly less effective unless they can be tailored to a user’s interests. The authors also note that if advertisers reduced their spending on online advertising in line with the reduction in effectiveness resulting from stricter privacy regulations, “revenue for online display advertising could fall by more than half from $8 billion to $2.8 billion.”[14] And as Beales notes, a reduction in ad revenue directly hurts online publishers since more than half of ad network revenue goes to publishers who host the ads.

It is therefore not surprising that U.S. Internet companies lead the world and European companies do not. European companies are at a disadvantage compared to U.S. companies because the government is essentially limiting their revenue to less than half of what they could otherwise earn. As a result, Europe has struggled to be an effective player in the Internet economy compared to the United States where there are significantly fewer restrictions.

As ITIF has noted, proposed privacy legislation provisions in the United States would restrict targeted online advertising by limiting the collection of certain types of data, requiring opt-in consent for collecting data, or providing mechanisms to encourage users to opt-out of targeted ads.[15] Like the European privacy regulations, these types of restrictions would limit targeted advertising and harm the Internet-powered economy. The kinds of privacy legislation now being proposed in Congress will reduce revenue flowing into the U.S. Internet ecosystem, which means not only fewer web sites and less valuable content, but also less spending by Internet companies on servers and bandwidth. The net result will be fewer jobs. In addition, if the Internet is less valuable to consumers because there is less useful content, applications and services, users are less likely to subscribe to broadband. In addition, privacy regulations such as requiring opt-in to collect or use data for targeted advertising will likely increase costs. Goldfarb and Tucker report that anecdotal evidence suggests that obtaining opt-in consent costs organizations approximately 15 Euros per user.[16]

Does this mean that policymakers should avoid all privacy regulations? Of course not. But it does suggest that policymakers should tread lightly and focus more on preventing harms from privacy violations than on legislating expensive and revenue-reducing regulations.[17] The evidence clearly suggests that the tradeoffs of stronger privacy laws result in less free and low-cost content and more spam (i.e. unwanted ads) which is not in the interests of most consumers.

Proponents of stricter privacy laws often ignore the benefits that online advertising confers on consumers. For example, Google and Facebook, two of the companies most vilified by privacy fundamentalists, are at the forefront of offering low or no-cost content, applications and services to consumers unimaginable a decade ago. Yet when these companies use targeted online advertising to fund their operations, privacy fundamentalists object. Unfortunately, these objections reflect the prevailing message of privacy fundamentalists that privacy trumps all other values. However, policymakers should recognize that privacy, as with any other value, must be balanced against other competing interests and can, as it will here, comes at a real financial cost—fewer jobs, less investment and a less robust Internet.

The Internet is a vital part of economic and social life and federal data privacy legislation should ensure that beneficial uses of data are not curtailed by overly-restrictive data sharing policies. Congress should not implement across-the-board reforms to privacy regulations without seeking a better understanding of how these changes will affect the Internet economy, and by extension, the overall economy and society.

Endnotes

[1] Robert Atkinson et al., “The Internet Economy 25 Years After .com,” (Washington, D.C.: Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, 2010) www.itif.org/files/2010-25-years.pdf.

[2] John Deighton and John Quelch, “Economic Value of the Advertising-Supported Internet Ecosystem,” (Hamilton Consultants, 2009) www.iab.net/media/file/Economic-Value-Report.pdf.

[3] Ibid.

[4] “Interactive Advertising Revenues to Reach US$147 Billion Globally by 2012, According to The Kelsey Group’s Annual Forecast,” press release, (Chantilly, VA: The Kelsey Group, 2008) www.kelseygroup.com/press/pr080225.asp.

[5] “Number of Mobile Devices Accessing the Internet Expected to Surpass One Billion by 2013, According to IDC,” IDC, press release, December 9, 2009, http://www.idc.com/getdoc.jsp?containerId=prUS22110509.

[6] “Internet Advertising Revenues Hit $5.9 Billion in Q1 ’10, Highest First-Quarter Revenue Level On Record,” IAB, May 13, 2010, www.iab.net/about_the_iab/recent_press_releases/press_release_archive/press_release/pr-051310.

[7] Robert D. Atkinson, “Federal Trade Commission Workshop on Journalism in the Digital Age,” (Washington, D.C.: Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, 2010) www.itif.org/publications/federal-trade-commission-workshop-journalism-digital-age.

[8] Jeff Jarvis, “History in the making in LA as online ads hit target,” The Guardian [UK] 12 Jan. 2009, www.guardian.co.uk/media/2009/jan/12/la-times-online-advertising.

[9] “YouTube channel earns college money for N.J. teen,” NJ.com, 7 April 2009, www.nj.com/news/index.ssf/2009/04/youtube_channel_earns_college.html.

[10] Robert Atkinson, “Google E-mail, What's All the Fuss About?” (Washington, D.C.: Progressive Policy Institute, 2004) www.ppionline.org/ppi_ci.cfm?knlgAreaID=140&subsecID=288&contentID=252511.

[11] Howard Beales, “The Value of Behavioral Targeting,” (2009) www.networkadvertising.org/pdfs/Beales_NAI_Study.pdf.

[12] Jun Yan, Gang Wang, En Zhang, Yun Jiang, & Zheng Chen, “How Much Can Behavioral Targeting Help Online Advertising?” (Madrid, Spain: WWW, 2009) www2009.eprints.org/27/1/p261.pdf.

[13] Avi Goldfarb and Catherine E. Tucker, “Privacy Regulation and Online Advertising,” (2010) http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1600259.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Daniel Castro, “ITIF Comments on Draft Privacy Legislation,” (Washington, D.C.: Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, 2010) www.itif.org/files/2010-privacy-legislation-comments.pdf.

[16] Avi Goldfarb and Catherine E. Tucker, “Privacy Regulation and Online Advertising,”

[17] Daniel Castro, “Data Privacy Principles for Spurring Innovation,” (Washington, D.C.: Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, 2010) www.itif.org/files/2010-privacy-and-innovation.pdf.

Editors’ Recommendations

January 12, 2015

Barack Obama Presses Privacy, Data Breach Agenda Post-Sony

December 26, 2014

Who Governs the Online World?

December 19, 2014