How Congress Can Foster a Digital Single Market in America

In areas ranging from data privacy to content moderation, states are creating patchworks of regulation that confuse consumers, complicate compliance, and undermine the digital economy. It’s time for Congress to step in and establish a consistent national approach to digital policy.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Key Takeaways

Contents

Federal Preemption at a Glance. 5

The State-by-State Patchwork vs. The Digital Single Market. 6

Priority Areas for Federal Preemption. 7

Introduction

Technology has transformed virtually every aspect of American life since the country’s founding over two centuries ago. The authors of the Constitution never could have imagined many of the conveniences of the 21st century. Instead of walking or riding to the local store to buy goods, Americans can shop from the comfort of their own home and have those items delivered to their doorstep from anywhere in the world. Instead of printing pamphlets and distributing them by hand or writing articles for the local papers, Americans can share their thoughts and opinions instantaneously across borders to anyone with an Internet connection. And instead of meeting and demonstrating in town squares, Americans can engage in political activism and organization on social media.

As stark as these differences seem, the principles laid out in the Constitution have endured in today’s connected world. The Founders recognized that unimpeded interstate commerce was crucial to the success of their fledgling nation, which led them to include the Commerce Clause in the Constitution, giving Congress the power to regulate commerce with foreign nations and among the states.[1] By giving every business, from multinational corporations to local mom-and-pop shops, the ability to sell its products and services online and across borders, the Internet has made the Commerce Clause more relevant than ever.

Despite the Internet’s inherent interstate nature, states have passed or considered a host of legislation regulating various areas of digital policy, creating a “tower of Babylon” of conflicting regulations that raises the costs of doing business and confuses consumers. Just as state and local governments cannot restrict interstate commerce in the physical world, such as prohibiting produce from other states or setting prices for interstate railroad freight, neither should they restrict interstate commerce on the Internet.

This report explores 10 of those areas—data privacy, data breach notification, children’s online safety, content moderation, digital taxes, e-commerce, right to repair, right of publicity, net neutrality, and digital identification—where state laws could create or have created a patchwork of regulation that confuses consumers and complicates compliance. In some areas, no federal regulation exists, leaving states to pick up the slack. In other areas, some federal regulation exists, but there are gaps where states have created rules of their own. In all areas, federal preemption to create a single national standard would benefit businesses, consumers, and the economy. This report enumerates 12 recommendations for the U.S. government to establish a consistent national approach to digital policy:

1. Congress should form a bipartisan U.S. Digital Single Market Commission to draft legislation for areas for federal preemption.

2. Congress should pass comprehensive federal data privacy and security legislation that preempts state laws, including AI and biometric privacy laws and data breach notification laws.

3. Congress should pass a moratorium on state children’s online safety legislation and later pass federal legislation based on recommendations from the U.S. Digital Single Market Commission.

4. Congress should enable noninvasive online age verification by providing funding for the research and development of age estimation technology using AI and mandating states implement electronic forms of identification.

5. Congress should ban taxes on wireless services and discriminatory taxes on digital goods and services that do not have a physical component.

6. States should continue their ongoing work to streamline the taxation of e-commerce by creating common definitions, rules, and simplified tax rate structures.

7. Congress should pass legislation instructing the Alcohol and Tobacco Products Tax and Trade Bureau, Federal Trade Commission (FTC), and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to establish uniform regulations for shipping alcoholic beverages directly to consumers, pupillary distance for eyeglasses, and prescriptions for pet medication.

8. Congress should require states to recognize the legality and enforceability of records, signatures, and contracts secured over a blockchain.

9. Congress should preempt state right to repair laws by passing a consistent right to repair standard for electronics at the federal level.

10. Congress should establish a federal right of publicity that gives individuals the right to control the commercial use of their identity while allowing for fair use and other speech protected under the First Amendment.

11. Congress should outlaw nonconsensual pornography, including deepfake nonconsensual pornography, and create a special unit in the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) to assist victims of nonconsensual pornography.

12. Congress should pass the Improving Digital Identity Act to create a framework for deploying a digital ID system.

The United States needs a single set of rules for the digital economy to maximize its potential economic and social benefits. These 12 recommendations represent the first strides the federal government can take toward that goal. Most countries strive to do this at the domestic level as well as regional level, such as through interoperable digital trade policies on data protection. Even the European Union has attempted to create a digital single market by instituting a common set of regulations for its member states (albeit by overregulating digital technologies). To ensure the U.S. digital economy remains competitive, Congress should pass legislation to fully preempt state and local regulations of the digital economy, starting with the 10 issue areas covered in this report.

Federal Preemption at a Glance

Under America’s federalist system, the Constitution grants certain powers to the federal government—and distributes those powers among Congress, the executive branch, and the judiciary—and reserves other powers for the states.[2] This system is designed to give states control over areas they can most effectively regulate, such as law enforcement, education, local transportation, and parks. However, as the Commerce Clause indicates, the federal government should have control over cross-border issues. On these issues where the federal government has control, its laws can preempt state and local laws.

Depending on the issue, federal preemption has strengths and weaknesses, and there are some instances where states may be better equipped to regulate an issue than Congress. In America, states function as “laboratories of democracy,” a popular phrase that traces its origin back to former Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis. In 1932, Brandeis wrote that “a single courageous State may, if its citizens choose, serve as a laboratory; and try novel social and economic experiments without risk to the rest of the country.”[3] Successful state laws may eventually end up inspiring federal laws and unsuccessful state laws may serve as cautionary tales to prevent Congress from making the same mistakes.

Additionally, Congress is a deliberative body that often moves slowly on key issues in order to reach a strong bipartisan compromise. States are often able to move faster than the federal government, passing laws sometimes years ahead of Congress. Opponents of federal preemption on digital issues argue that this puts states in a better position than the federal government to react quickly to the ever-changing digital landscape.[4] Technology is constantly evolving, and Congress has been slow to react, especially compared with many states. For example, 12 states have passed their own comprehensive data privacy laws, whereas Congress has yet to even vote on one.[5]

Finally, many oppose federal preemption of state laws due to partisan preferences. In states with a single-party trifecta or supermajority, the laws typically represent the politics of one party more than the other. Democrats are likely to prefer laws passed by California or Colorado over Congress’s more bipartisan solutions, and likewise for Republicans, who might favor laws passed by Texas or Florida. Activists know that if they can get a few states, ideally large ones such as California or Texas, to impose their preferred regulations, most companies will simply implement them nationwide and they thus become the de facto regulations for the country. This strategy is the domestic version of what the EU hopes will happen globally with its regulations (called the “Brussels effect”). These dynamics can make reaching a solution in Congress even more difficult, since one or both parties may have already gotten their way, so to speak, in various different states and feel that any sort of compromise is a step in the wrong direction.[6]

When it comes to digital policy, however, arguments for federal preemption of state laws outweigh the arguments against preemption. First and foremost, when an issue impacts Americans regardless of where they live, it is important for Congress to set a national standard that applies to the entire country. Since the Internet transcends borders, this argument for federal preemption is especially relevant to many of today’s emerging issues. It is easier and more affordable for businesses that have customers in multiple states—as many businesses in the modern age do—to comply with a single set of federal regulations than to keep up with all 50 states passing their own regulations on the same issues. There is also no practical reason why Americans’ access to digital services or ability to exercise their rights online should vary depending on their state of residence.

When it comes to digital policy, arguments for federal preemption of state laws outweigh the arguments against preemption.

Likewise, when it comes to issues that impact organizations that operate in multiple states—including digital issues—it is easier for stakeholders to bring their concerns to Congress than to repeatedly explain their concerns to multiple different state legislatures. On issues ranging from data privacy to right to repair laws for electronics, organizations representing various business or consumer interests have had to participate in many of the same discussions and debates over and over in each state where legislation is introduced, expending many times more resources than if they could concentrate their efforts on a single federal debate. In this environment, many stakeholders simply cannot afford to participate in these discussions and state policymakers may overlook important considerations.

Finally, contentious issues require compromise for a lasting solution. Since the 2022 elections, 39 state governments have had a single-party trifecta wherein one party controls both chambers of the state legislature and holds the governorship. In some of these states, that party also has a supermajority in the legislature, defined as either at least 60 percent or two-thirds of the seats.[7] By comparison, in recent decades, the federal government has usually been divided, with one party holding the White House and another party holding at least one chamber of Congress.[8] Because of this divide, bipartisan compromise is more necessary in Congress than in many state legislatures, leading to federal laws that reflect a balance of both parties’ goals.

The State-by-State Patchwork vs. The Digital Single Market

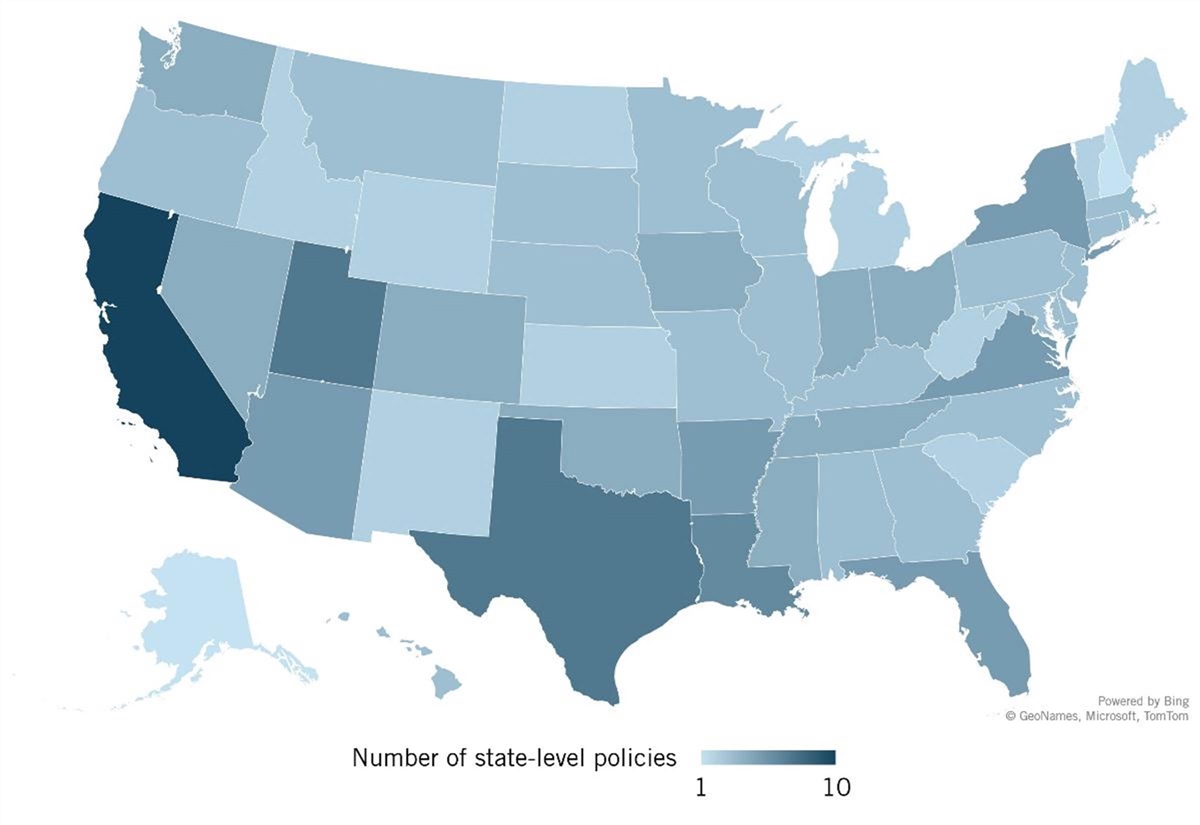

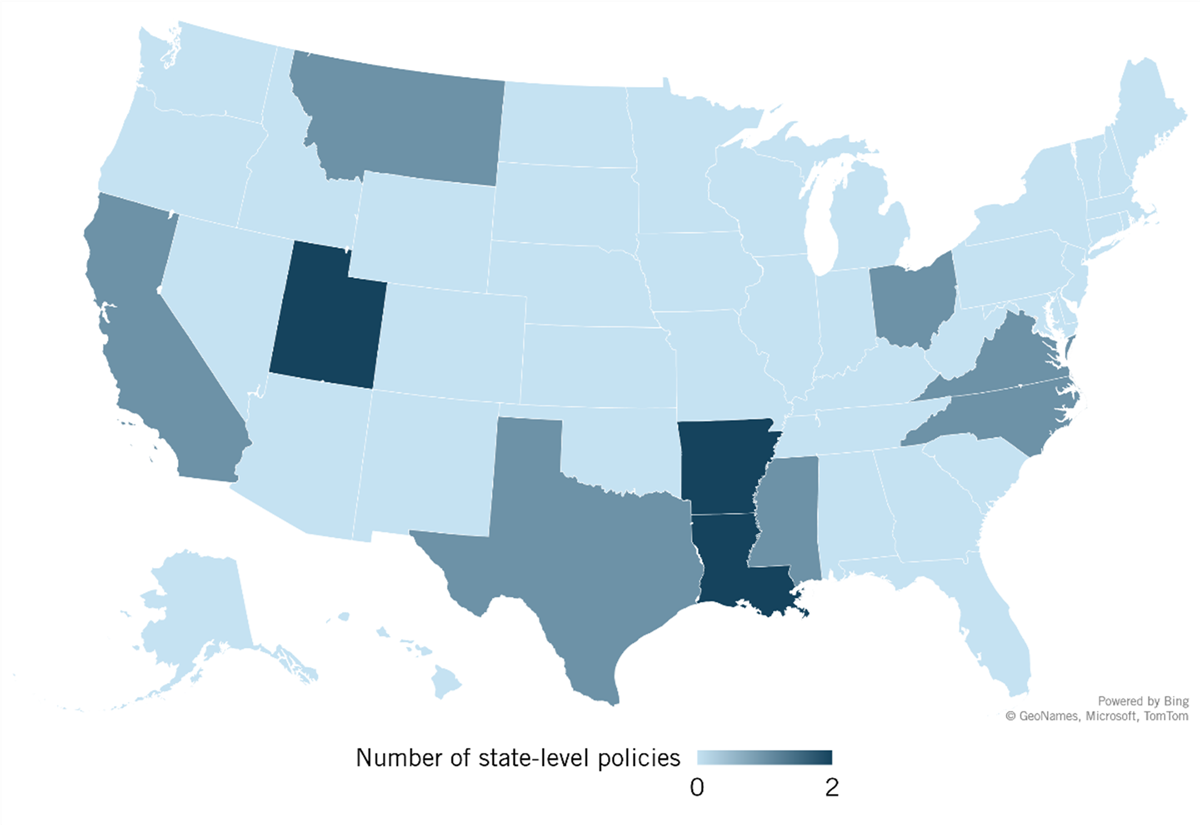

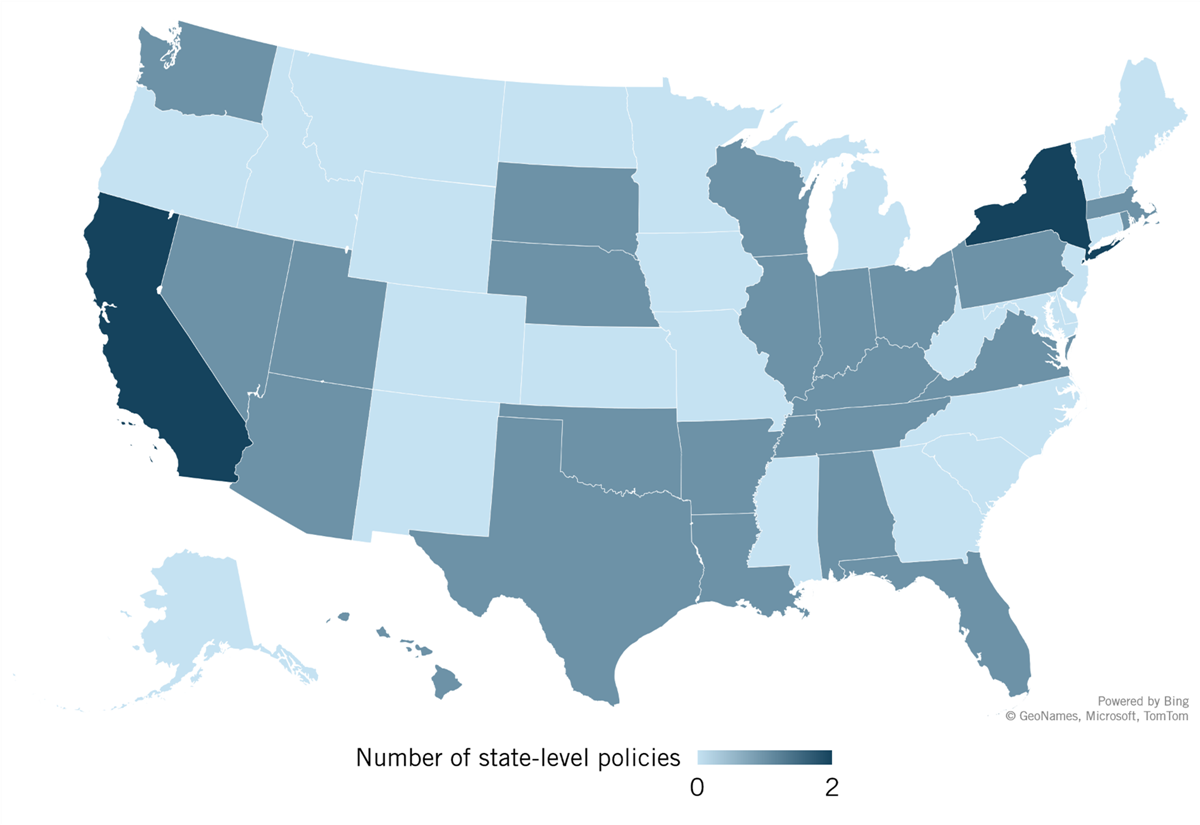

In part because Congress has been so slow to move on key digital issues, a patchwork of state laws has emerged that threatens to cost American businesses and the economy billions and further stymie progress on a federal level. Even on issues where federal regulation already exists, some states have passed conflicting regulations of their own. Figure 1 shows how many digital policies states have enacted in the areas of data privacy, data breach notification, children’s online safety, content moderation, digital taxes, e-commerce, right to repair, right of publicity, net neutrality, and digital identification. This patchwork is difficult and expensive for businesses to comply with, creates confusion for consumers, and needlessly fragments the U.S. digital market.

Figure 1: Number of state digital policies enacted in 10 key areas as of February 2024

In comparison, a digital single market refers to the concept of a national market for digital goods and services free from artificial barriers and differing rules between states. Establishing a digital single market in the United States would require Congress and regulatory agencies to create a uniform set of digital regulations in areas such as data privacy, data breach notification, children’s online safety, content moderation, digital taxes, e-commerce, right to repair, right of publicity, net neutrality, and digital identification. Creating one set of rules would ensure all Americans receive equal protections, minimize compliance costs for businesses, and remove unnecessary barriers to innovation.[9]

In 2015, the European Union launched a major initiative to establish a digital single market that harmonizes many laws affecting digital products and services. This initiative aims to boost economic growth, jobs, competition, investment, and innovation in the EU by increasing access to digital goods and services, creating the right conditions for innovation, and maximizing the potential growth of the digital economy.[10] While Europe has made considerable progress, it still has a way to go, in part due to continued resistance from national governments.[11] However, it is important to note that even when lawmakers devise a single set of rules, they must also create the right policies. Though the EU has created a digital single market, it has imposed burdensome regulations on its digital economy, creating barriers to innovation that the United States should not replicate.

By comparison, while the United States has established uniform regulations in certain digital policy areas, there are many gaps in these regulations and areas left unexplored. States have filled in these gaps with their own regulations. In some cases, this patchwork is better than no regulation—though federal regulation would still be preferrable—but in other cases, it has led to problematic laws that impose unnecessary costs on businesses and create barriers to innovation. In all cases, a single federal standard would reduce confusion and simplify compliance.

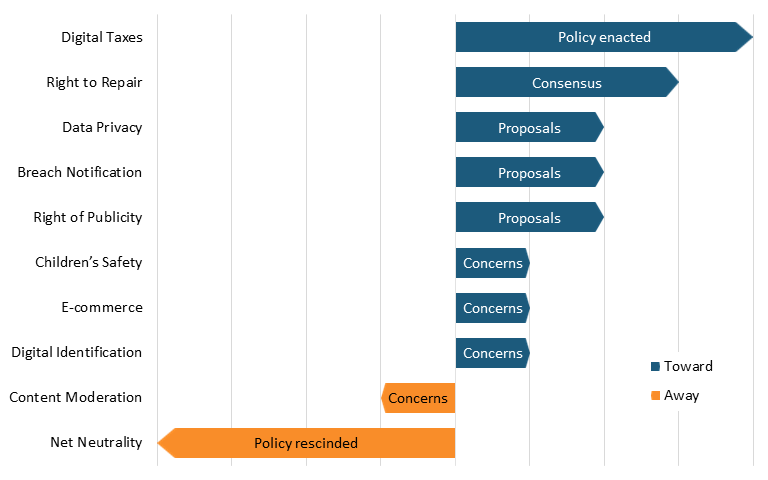

While the federal government should step in to preempt inconsistent state laws in many digital policy areas, there remains a key role for states to play in enforcement. For example, while Congress should set a national standard for data privacy and data breach notification, effective enforcement should involve both the FTC and state attorneys general. On other issues, such as taxes on e-commerce, states should continue imposing sales tax but coordinate their efforts at a national level to establish uniformity. Figure 2 shows where key digital policy issues stand in the process of moving toward or away from federal preemption, where the first step in either direction is that concerns have been raised, the second step is that proposals have been introduced, the third step is that consensus has been reached, and the final step is that policies have been enacted or rescinded.

Figure 2: Digital policy issues moving toward and away from federal preemption as of February 2024

Priority Areas for Federal Preemption

There are a series of digital issues where states have passed or are considering conflicting, often problematic laws that pose problems for businesses and consumers. Federal preemption in these areas is crucial to make progress toward a U.S. digital single market. These areas include data privacy, data breach notification, children’s online safety, content moderation on social media and other online services, taxes on Internet access and e-commerce, regulation of certain types of e-commerce, right to repair electronic devices, right of publicity, net neutrality, and digital identification.

Data Privacy

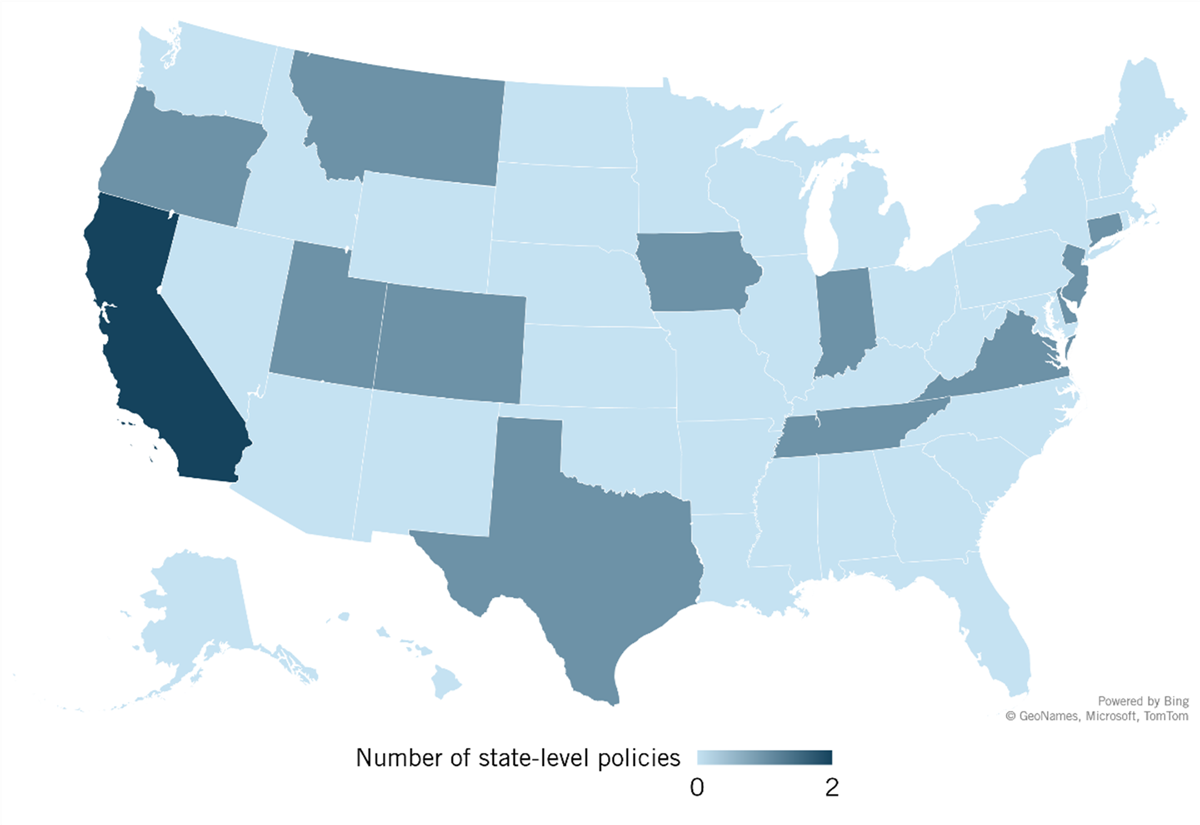

The United States’ lack of comprehensive federal data privacy legislation has been a central issue within the larger debate on federal preemption in digital policy for the past several years. The EU passed its General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in 2016, which took effect in 2018, and since then, several countries outside Europe have followed suit with comprehensive privacy regulations of their own.[12] In the absence of federal action, California became the first state in the United States to pass a privacy law, the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), in 2018, which took inspiration from the GDPR.[13]

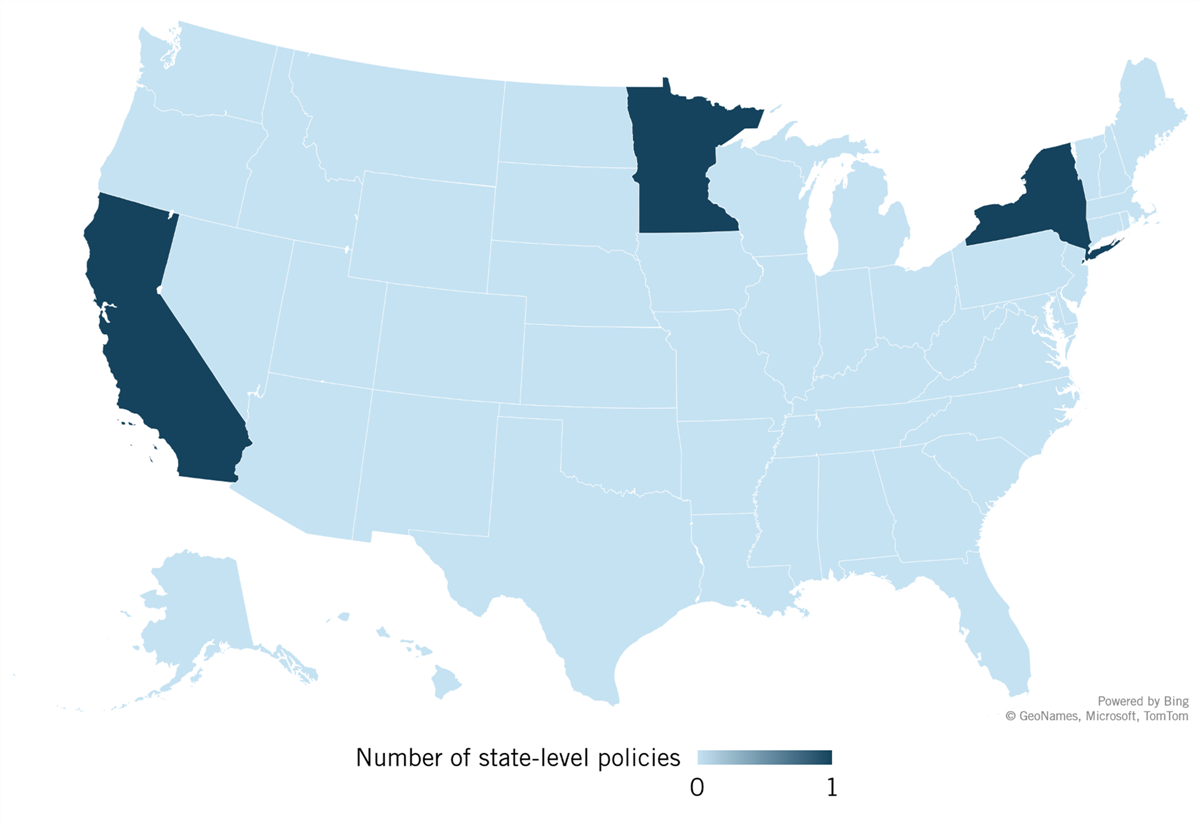

Figure 3: State-level policies on data privacy as of February 2024

California’s law opened the floodgates of state privacy legislation. By the end of 2023, 11 other states had passed comprehensive privacy laws, with bills introduced in many of the remaining 39 states.[14] These laws typically create new consumer rights, which may include the right of consumers to access, port, delete, or rectify their personal data; the right to opt out of sales of their personal data to third parties or data processing; and the right to seek civil damages for violations. State privacy laws also create new obligations for businesses, such as fulfilling transparency requirements, hiring and retaining data protection officers, performing privacy audits, obtaining opt-in consent from users, minimizing the amount and types of data collected, and disclosing the purpose of data collection.

Not only does the current state-by-state approach to privacy impact consumers, whose privacy rights vary depending on where they live, it has an enormous impact on businesses, which must comply with the privacy laws of every state where their users live. This is an expensive process, including the costs of coming into compliance with all these laws and paying any legal fees associated with noncompliance. The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) estimated in 2022 that if all 50 states passed their own comprehensive privacy laws, businesses would pay out-of-state costs between $98 billion and $112 billion per year.[15]

In addition to these comprehensive privacy laws, some states have also passed or considered targeted legislation to address privacy issues related to specific technologies, such as artificial intelligence (AI) and biometrics. Six states—Illinois, Maryland, New York, Oregon, and Texas—had biometric privacy laws as of December 2023 and many more have proposed such legislation.[16] Illinois set the standard for these laws with its Biometric Information Privacy Act, which requires written, informed consent for the collection and use of any biometric data and created a wave of expensive lawsuits that deterred some companies from operating or offering certain services in Illinois.[17] Where AI is concerned, states are only beginning to consider and pass their own legislation, but there is a real risk of such laws imposing even more costs on businesses and creating significant barriers to innovation.

Though it has not passed comprehensive privacy legislation, Congress has passed data privacy laws that govern certain sectors or types of data, though these laws do not currently prevent states from passing laws of their own as long as those laws do not contradict federal law. For example, Congress passed the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) in 1996, which applies to personally identifiable information that healthcare and health insurance providers collect on individuals. The law prohibits providers from sharing patients’ medical record or payment history with anyone other than patients and their authorized representatives, with limited exceptions. Providers must also notify patients when they disclose or give individuals access to their personal health information and take reasonable measures to ensure communications with patients are confidential.[18]

Congress passed the Financial Services Modernization Act, also known as the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act, in 1999, which applies to personal information that financial institutions collect on individuals. Among other provisions, the law requires financial institutions to explain what information they collect about consumers and how that information is shared, used, and protected. Consumers have a right to opt out of their information being shared. The law also establishes cybersecurity requirements for financial institutions to protect consumers’ information.[19]

Finally, Congress passed the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) in 1998, effective 2000, which applies to personal information collected online from children under 13. Under the law, online services directed at children must explain how they collect information from children under 13 in their privacy policy, provide parents with notice on their data collection practices, obtain parental consent to collect information from children under 13, give parents access to their children’s data, protect the confidentiality and security of children’s personal information, and retain data on children under 13 only as long as necessary to fulfill the purpose for which it was collected.[20]

In response to the growing need for comprehensive federal data privacy legislation, Congress has considered many different bills, but none have reached a floor vote, and the differences between these bills highlight the remaining divisions and need for compromise between and within parties on key privacy issues.[21]

Data Breach Notification

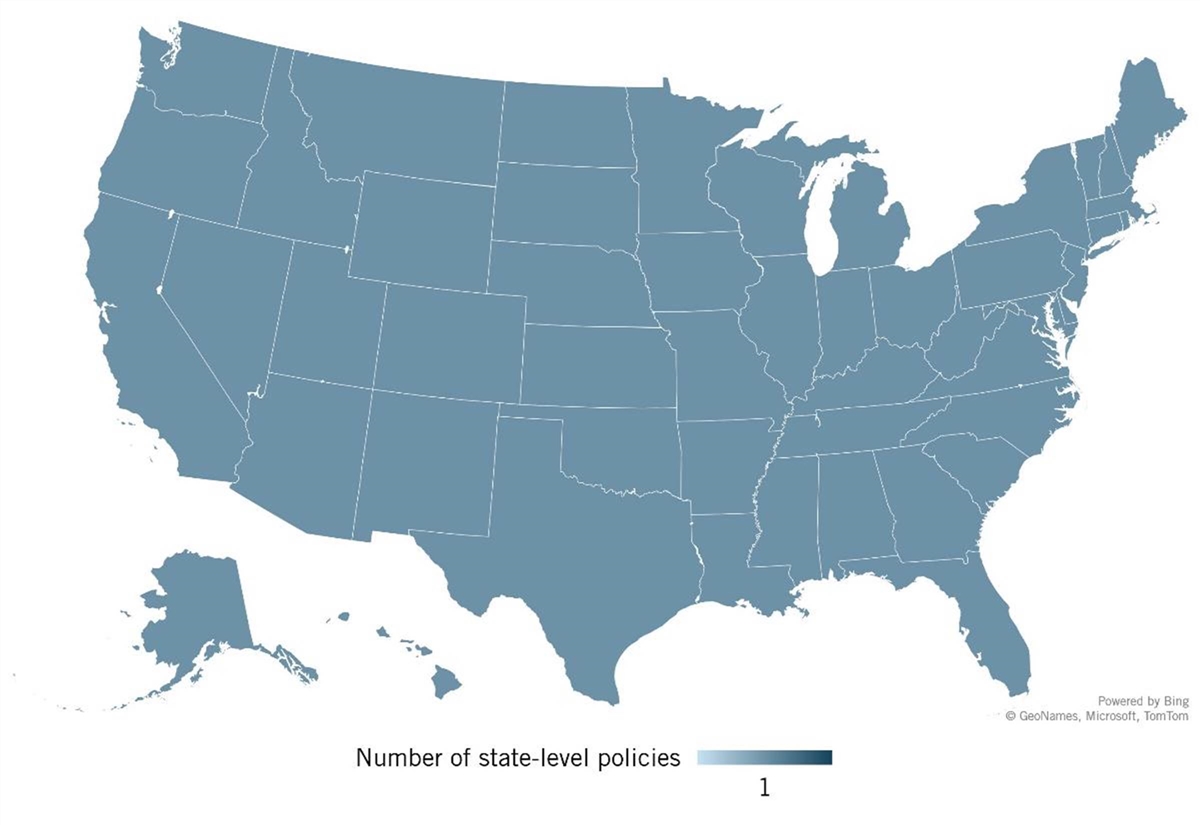

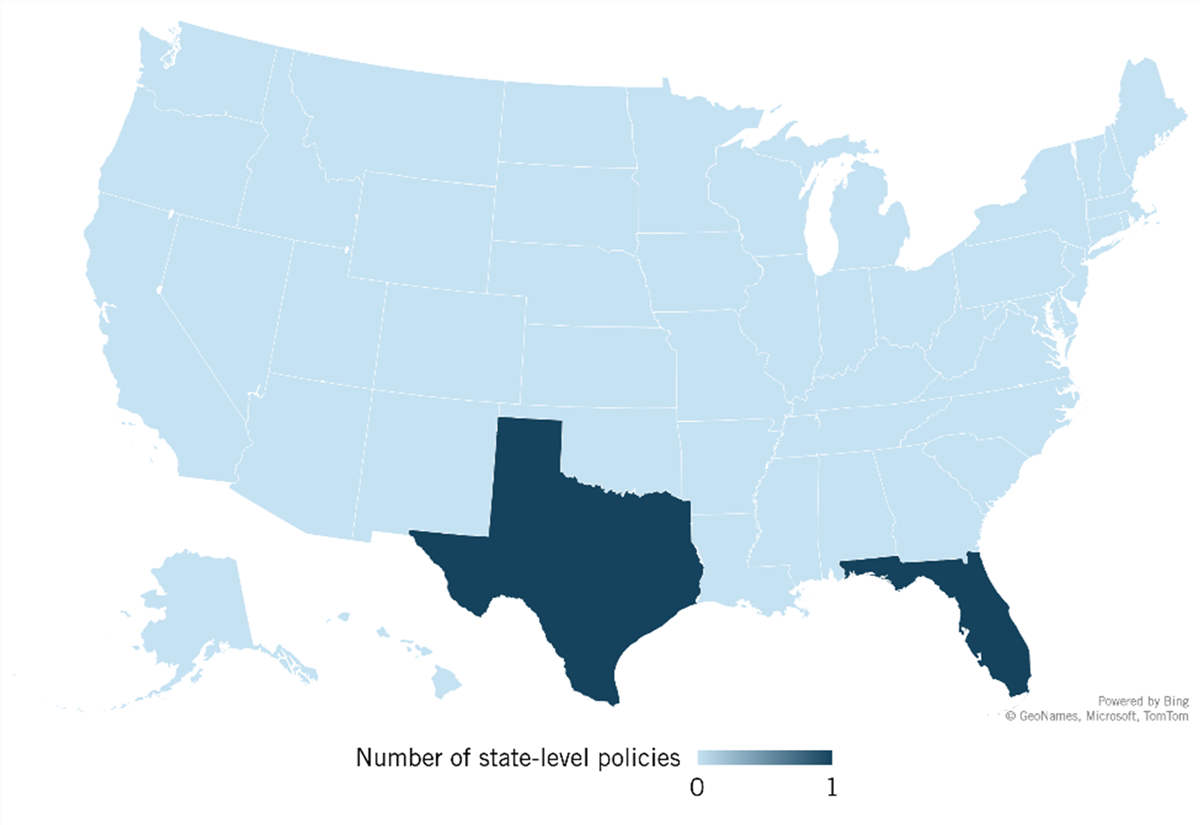

While a growing number of states have passed comprehensive data privacy legislation, all 50 of them have data breach notification laws, which require organizations to notify users of data breaches involving their personal information.[22] These laws vary from state to state on a number of factors, including which entities the laws applies to, how the laws define personal information and what constitutes a data breach, whom organizations must notify in the event of a breach, and how and when organizations must notify these individuals.

Figure 4: State-level policies on data breach notification as of February 2024

When a data breach affects an organization with users in multiple states, complying with each state’s laws is a complicated process. Additionally, different states’ laws afford consumers different protections. For example, some data breach notification laws only apply to unencrypted data, while others apply to unencrypted or encrypted data. Some data breach notification laws only apply to unauthorized acquisition of personal data while others apply both to unauthorized acquisition and unauthorized use of personal data, protecting consumers in the case of data misuse, such as when Cambridge Analytica gained illicit access to 87 million Facebook users’ data.[23]

There are federal regulations regarding breaches of certain types of information. HIPAA-covered entities must notify affected individuals of breaches involving their health information under the HIPAA Breach Notification Rule.[24] Additionally, any business not covered by HIPAA that maintains an electronic record of individuals’ identifiable health information or interacts with businesses that maintain such records must notify affected individuals of breaches involving their identifiable health information under the FTC’s Health Breach Notification Rule.[25]

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) requires telecommunications, Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP), and telecommunications relay providers to report breaches, including misuse, of customers’ personally identifiable information, with updates to these rules in 2023 that expanded their scope.[26] Finally, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) adopted a rule in 2023 requiring U.S. public companies and foreign companies that do business in the United States to disclose cybersecurity incidents to their investors.[27]

In order to create a uniform standard that applies to all data breaches of personal information, Congress has considered data breach notification legislation both as standalone bills and as provisions within comprehensive data privacy bills, but none of these bills have passed.[28]

Children’s Online Safety

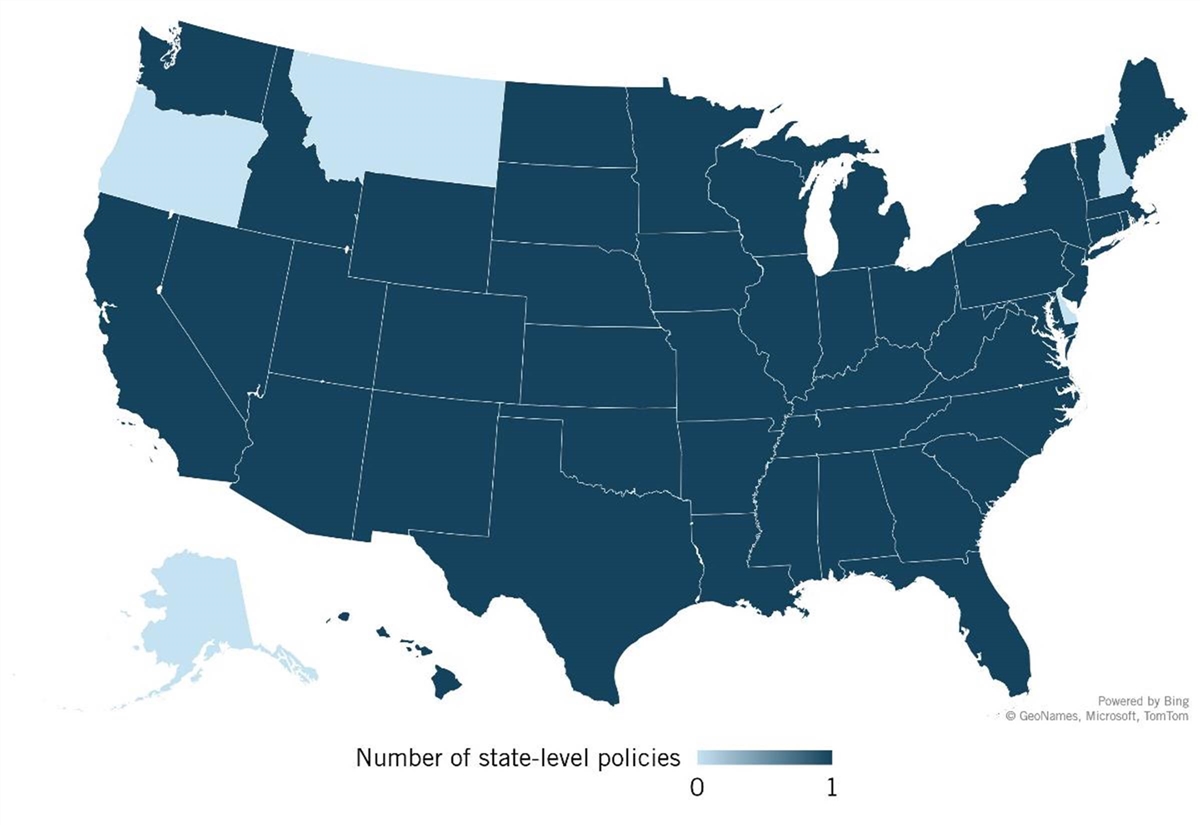

Several states have passed laws attempting to address safety concerns facing children online. Thus far, these laws have fallen into two categories: age-appropriate design codes (AADCs), which establish standards online services must follow to make their services safe for children, and age verification requirements, which gatekeep certain online services from users under a certain age either entirely or without parental consent.

Figure 5: State-level policies on children’s online safety as of February 2024

The California Age-Appropriate Design Code Act (CAADCA), enacted in 2022, requires that online services children are “likely to access”—not just services targeted at children—consider the best interests of children and prioritize children’s privacy, safety, and well-being over commercial interests. These services must complete a Data Protection Impact Assessment before offering any new online service, product, or feature that children are likely to access to determine whether the design of the service, product, or feature could harm children or expose them to harm. Any online service in violation of the CAADCA could face fines of up to $2,500 per affected child for negligent violations and up to $7,000 per affected child for intentional violations.[29]

Several other states—including Connecticut, Illinois, Maryland, Minnesota, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Oregon, and Texas—have introduced their own AADCs, though none have passed.[30] This is likely at least in part due to the ongoing lawsuit NetChoice, an industry trade association, filed against the CAADCA, arguing that the law gives the California state government unconstitutional control over online speech by punishing online services if they do not protect underaged users from “harmful or potentially harmful” content and prioritize content that promotes minors’ best interests. A federal judge granted a preliminary injunction against the law while the case goes forward.[31] Other states will likely wait for the outcome of the case before moving forward with their own legislation.

Meanwhile, multiple states have introduced or passed legislation that would require certain online services to verify the ages of their users and either block access or require parental consent for users under a certain age, either 16 or 18. Some of these laws—in Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Texas, Utah, and Virginia—target online services that provide adult content.[32] Others—introduced in Pennsylvania and Wisconsin and passed in Arkansas, Connecticut, Louisiana, Ohio, and Utah—target social media platforms.[33]

Like the CAADCA, some of these laws are facing lawsuits. For example, NetChoice sued Arkansas over its Social Media Safety Act, arguing that the law infringes on minors’ free speech rights by denying them access to social media without parental consent and infringes on adults’ free speech rights by requiring them to prove their age in order to access these platforms, which are important tools for communication in the digital age. Once again, a federal judge granted a preliminary injunction against the law.[34] NetChoice later filed similar lawsuits against Utah and Ohio over their age verification laws for social media; these cases are still in the early stages.[35] Cases filed against Louisiana’s, Texas’s, and Utah’s age verification laws for adult content are also ongoing.[36]

States’ gatekeeping access to certain online services comes with serious implications for these services and their users. In order to verify users’ ages, these services may have to collect and retain information from government-issued forms of identification, which include not only an individual’s date of birth but other sensitive personal data such as their full name and address. In order to obtain parental consent, online services will have to collect additional sensitive personal data to verify the relationship between parent and child.

This data collection poses privacy risks and may deter some users from using certain online services. For example, some users may not be comfortable with Chinese-owned TikTok having a copy of their government ID, and many users would not be comfortable with adult websites knowing their full name and address. Additionally, adults without a form of government-issued identification would lose access to social media and adult online services. This includes as many as 7 percent of Americans, with rates even higher among low-income individuals, Black and Hispanic individuals, and young adults.[37]

Of course, gatekeeping access to adult online services, where the majority of content is inappropriate for minors, is different from gatekeeping access to social media, where only some content is inappropriate for minors. But both approaches carry free speech implications, as adults have a right to access legal content, including sexually explicit content.[38]

Congress has not passed any legislation governing children’s online safety since COPPA, though there are a few bipartisan bills in Congress that address children’s online safety issues. The Eliminating Abusive and Rampant Neglect of Interactive Technologies (EARN IT) Act would require online services to follow best practices to prevent child exploitation, determined by a National Commission on Online Child Exploitation Prevention and the attorney general, or face potential liability for third-party content that violates child exploitation law.[39]

The Kids Online Safety Act (KOSA) would require social media platforms to provide minors and their parents with additional safeguards and tools, establish a duty of care for social media platforms to prevent and mitigate harm to minors, and give academic researchers and nonprofit organizations access to certain datasets from social media platforms.[40] The Strengthening Transparency and Obligations to Protect Children Suffering from Abuse and Mistreatment (STOP CSAM) Act would require large online services to submit annual reports detailing their policies and reporting systems for child sexual abuse material and report and remove planned or imminent child exploitation.[41]

The Children and Teens’ Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA 2.0) would extend COPPA’s protections for users under 13 to users between age 13 and 16, ban targeted advertising to children, give children and their parents a right to delete their personal information, and expand COPPA’s scope to cover any online services that are “reasonably likely to be used” by children and protect any users who are “reasonably likely to be” children.[42]

Though these proposals address important issues and include some beneficial provisions, critics argue that in their current form, the EARN IT Act, KOSA, and STOP CSAM Act could incentivize online services to engage in censorship or scan their users’ posts and messages, thereby violating user privacy and potentially undermining end-to-end encryption.[43] Meanwhile, COPPA 2.0 would create additional, overly burdensome requirements for businesses that already comply in good faith with existing children’s privacy and safety standards.

The EARN It Act could also open the door for more state-by-state fragmentation, as it would allow states to impose lower standards for criminal and civil liability of online services. The current federal standard only holds online services accountable when they “knowingly” fail to remove CSAM, but some states hold online services accountable for “recklessly” or “negligently” failing to remove CSAM. Rather than complying with different standards in each state, which would be a complicated endeavor, online services are likely to comply with the strictest state law, creating a race to the bottom and impacting users in all 50 states.[44]

Content Moderation

For many years after the advent of online forums and, later, social media, states did not pass laws governing content moderation on these and other online services. Instead, the United States had a federal standard, established in Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, which shields online services and their users from liability for third-party content.[45] In other words, Section 230 protects online services and users for hosting or sharing someone else’s potentially objectionable content, as well as for good faith efforts to block or remove someone else’s potentially harmful or objectionable content. Credited as a foundational law for the modern Internet, Section 230 enables a wide variety of online services to grow and thrive, benefiting businesses, consumers, and the Internet economy, though the law is not without its detractors.[46]

Figure 6: State-level policies on content moderation as of February 2024

Section 230 explicitly preempts conflicting state laws.[47] But in recent years, Section 230 has become a popular topic of debate, with policymakers and stakeholders from both sides of the aisle arguing for changes to the law or even a full repeal. Common critiques include that Section 230’s liability protections are too broad, giving online services too much freedom to ignore potentially objectionable content and censor users.[48] Reflecting this, multiple states have considered and passed legislation to address content moderation, especially on social media, and some of these laws have faced legal challenges for conflicting with Section 230.[49]

Two notable cases came out of Florida and Texas in 2021. Florida’s law, S.B. 7072, fines social media platforms $250,000 per day for de-platforming any political candidate running for statewide office and $25,000 per day for de-platforming any other political candidate. It also allows Floridian users to sue social media platforms for censoring or de-platforming them.[50] Meanwhile, Texas’s law, H.B. 20, prohibits large social media platforms from “censoring” users, defined as “to block, ban, remove, de-platform, demonetize, de-boost, restrict, deny equal access or visibility to, or otherwise discriminate against expression,” and allows Texan users to sue platforms.[51]

These laws arose out of Republicans’ claims that social media companies, particularly large ones, are biased against conservatives, unfairly censoring conservative content and de-platforming conservative users. But penalizing platforms for blocking or removing content, in addition to running counter to Section 230, would have unintended consequences that change social media for the worse. Platforms would likely have to change the way they moderate content to avoid costly fines and legal battles, removing less potentially objectionable content, including content that many users do not want to see on their feeds, such as spam, pornography, violence, disinformation, hate speech, and bullying.

Technology industry groups NetChoice and the Computer and Communications Industry Association (CCIA) challenged both laws in court for conflicting with Section 230 and allegedly violating the First Amendment by dictating what speech online services can and cannot remove.[52] The Supreme Court announced that it will review both laws in its 2023–2024 term.[53] If the Supreme Court upholds these laws, more states are likely to pass their own content moderation legislation conflicting with Section 230. However, even if the Supreme Court strikes these particular laws down, states may still try to regulate content moderation in ways that do not conflict with Section 230 or include content moderation provisions in privacy and online safety laws.

Digital Taxes

Taxes on Internet access and e-commerce were some of the first issues in which the federal government intervened to preempt a patchwork of state laws. Initially, states could levy taxes on Internet access, which created an additional barrier to access when the Internet was still relatively new. In 1995, only 14 percent of American adults had Internet access, according to the Pew Research Center, and 42 percent of American adults had never heard of the Internet.[54]

Figure 7: State-level policies on e-commerce sales tax as of February 2024

Because so few ordinary consumers could access the Internet at home, e-commerce was also a relatively new concept, but poised for tremendous growth. This posed unique challenges for taxation. When a consumer purchases something in a brick-and-mortar store, the buyer and seller are both in the same physical location. But when a consumer shops online, they can purchase goods and services from anywhere. The buyer may be in Virginia while the seller may be in Maine. This raises questions of which state can tax the transaction, and whether both states can tax the same transaction. It also raises the question of whether states should tax e-commerce transactions at the same rate as transactions in person, via mail order, or over the phone.

Congress addressed all these issues when it passed the Internet Tax Freedom Act (ITFA) in 1998.[55] The law imposed a three-year moratorium on state and local taxes on Internet access, though it included a grandfather clause whereby states that had already imposed taxes on Internet access—including Hawaii, New Mexico, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota, Texas, and Wisconsin—could maintain these taxes.[56] The ITFA also prohibited multiple and discriminatory taxes on e-commerce.

A multiple tax exists when multiple states impose a tax on the same transaction. As in the case of a buyer in Virginia purchasing from a seller in Maine, a multiple tax would exist if both Virginia and Maine taxed the transaction. Meanwhile, a discriminatory tax exists when a state imposes a different tax rate on e-commerce and nonelectronic commerce. For example, if the hypothetical Virginian buyer purchased a book online, a discriminatory tax would exist if Virginia charged a higher tax than if the buyer had purchased the same book from a brick-and-mortar store.

The ITFA’s moratorium on taxes on Internet access removed a barrier to Internet adoption, and its moratorium on multiple and discriminatory taxes on e-commerce ensured that states could not, intentionally or otherwise, disincentivize consumers from shopping online. In the years since the ITFA’s passage, e-commerce has flourished. By the turn of the millennium, 22 percent of American adults had purchased a product online.[57] Compare that with today, when over half of American consumers shop online at least once a week and only 6 percent have never shopped online.[58]

Congress extended the ITFA’s moratorium multiple times before passing the Permanent Internet Tax Freedom Act (PITFA) in 2016, which transformed the moratorium into a permanent ban. The PITFA also set an expiration date of June 30, 2020, for the ITFA’s grandfather clause exempting certain states from the ban on taxes on Internet access, and now all states are prohibited from taxing Internet access.[59]

There are still a few gaps remaining in federal preemption when it comes to taxes on e-commerce. First, because wireless services—Internet access via mobile phones, tablets, and other handheld devices—did not exist when Congress passed the ITFA, the ban on taxes on Internet access only applies to dial-up, cable, digital subscriber line (DSL), fiber, and satellite services. This has a disproportionate impact on low-income individuals. According to the Pew Research Center, American adults with an annual household income under $30,000 are more likely to access the Internet via a smartphone (76 percent) than a desktop or laptop computer (59 percent).[60]

Additionally, despite the ban on multiple and discriminatory taxes, taxation of e-commerce is still a complex and confusing system. Each state can set its own rules on what can be taxed and how much those taxes are. Online retailers that sell to many different states must keep up with each state’s different taxes. Beginning in 2000, several state governments came together to simplify the process for registering with their tax agencies and create common definitions, rules, and simplified rate structures, culminating in the Streamlined Sales and Use Tax Agreement (SSUTA), but currently only 24 states have adopted these measures.[61]

Finally, under ITFA, states can impose discriminatory taxes on digital goods and services that do not have a physical component, taxing them at different rates than their physical counterparts. This applies to many digital products such as movie and music downloads, e-books, games, and software. This goes against the ITFA’s goal of prohibiting states from disincentivizing e-commerce. This discrepancy could become an even greater problem with the growth of augmented and virtual reality, which immerse users in partially or fully digital worlds that offer a wide variety of digital goods and services for purchase that have no physical components.

E-commerce

There are a number of non-tax-related e-commerce issues wherein a federal standard would benefit businesses and consumers. Once again, the cross-border nature of e-commerce lends itself to federal preemption, which creates consistency across the United States instead of subjecting businesses to a complicated patchwork of state regulation that can be equally confusing for consumers.

First, there are specific product categories sold online that are currently subject to state regulation for various reasons. These include age-restricted products, such as alcoholic beverages, as well as medical products, such as eyeglasses and pet medication. Online alcohol sales are currently subject to many different conflicting state laws. The legality of shipping alcoholic beverages directly to consumers in different states varies depending on the type of alcoholic beverage, the type of business that offers the delivery, whether a local business packaged the alcoholic beverage, whether a business has a certain permit, whether an intermediary performs the delivery, whether the buyer placed the order in person, and whether the delivery provider checks the buyer’s ID. Currently only one state, Utah, outlaws direct-to-consumer alcohol delivery completely.[62]

When it comes to eyeglasses, consumers need certain information from their eye doctors in order to buy glasses online. One of these pieces of information is the individual’s pupillary distance, or the distance between the centers of the individual’s pupils, which is used to accurately center the lenses in a pair of glasses. The FTC requires eye doctors to provide patients with a copy of their prescription whether or not a patient asks for it but leaves the information eye doctors must provide in the prescription up to states. Some states, but not all, require eye doctors to include this information in patients’ prescriptions, meaning some consumers may not have enough information to order their own glasses online.[63]

Finally, when it comes to buying pet medications online, the FDA requires all pharmacies to be licensed with their state board of pharmacy or similar agency, and pharmacies and other websites cannot sell prescription pet medication without a valid prescription from a licensed veterinarian.[64] However, there are gaps in federal regulation. Not all states have laws requiring veterinarians to provide prescriptions upon request, which would prevent consumers from buying pet medications from their pharmacy of choice, online or otherwise.[65] Some states allow veterinarians to charge a fee for writing a prescription, while others prohibit this practice.[66]

Outside specific product categories, another area for federal preemption in e-commerce—or more accurately, updated federal preemption—is electronic signatures (e-signatures). Congress initially passed the Uniform Electronic Transactions Act (UETA) in 1999, which provided a legal framework for e-signatures that states could adopt. States that have adopted the UETA cannot deny the legality or enforceability of a record, signature, or contract because it is electronic, and an electronic record or signature will satisfy any legal requirement for a written record or signature. The UETA includes exceptions for birth, wedding, and death certificates, and many states also include exceptions for wills and related documents. Congress also passed the Electronic Signatures in Global and National Commerce (ESIGN) Act in 2000, which made e-signatures legal in every state and U.S. territory, including those that did not adopt the UETA.[67]

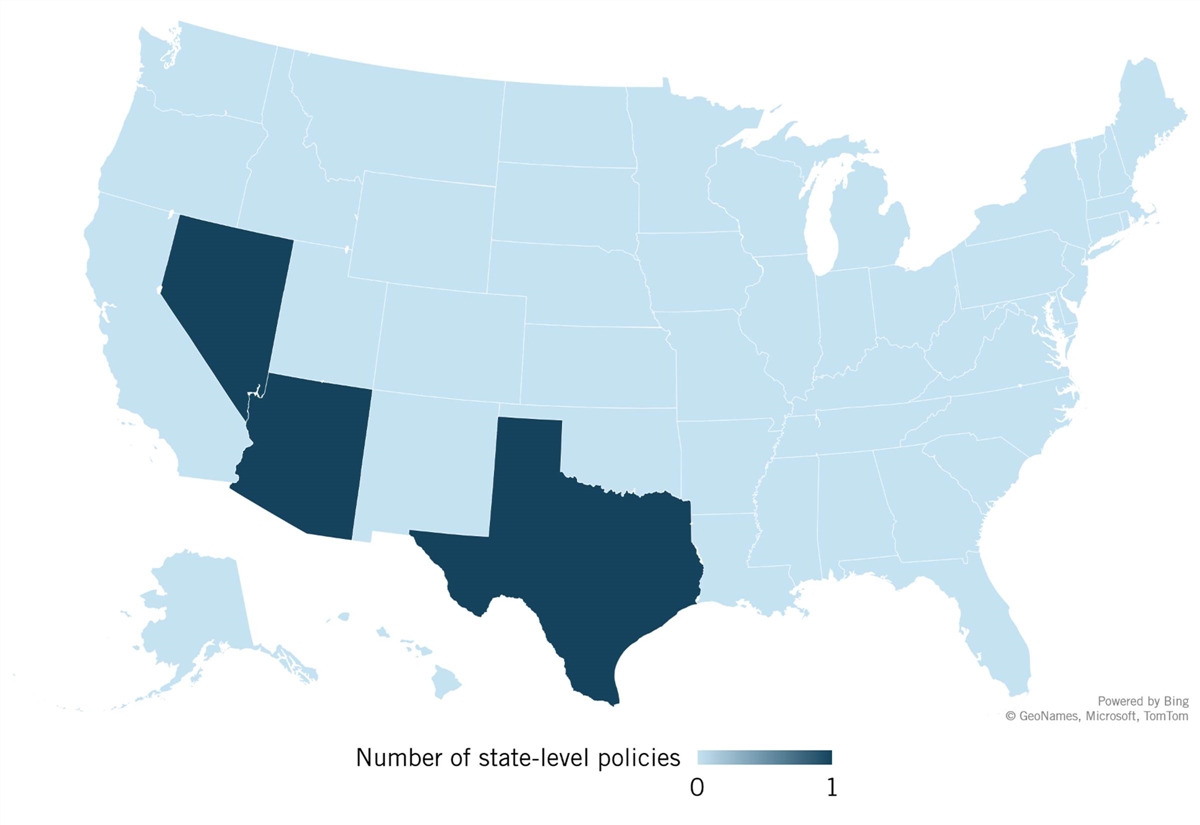

Figure 8: State-level policies on blockchain signatures as of February 2024

Technology has advanced since the UETA and the ESIGN Act, with blockchain technologies providing new ways for individuals to electronically validate a record, signature, or contract. Blockchains are digital ledgers that record information that is distributed among a network of computers, eliminating the need for a central authority to establish authenticity. Arizona, Nevada, and Texas have amended their UETAs to include blockchain, but there is no federal requirement for all states to recognize records, signatures, and contracts secured over the blockchain.[68]

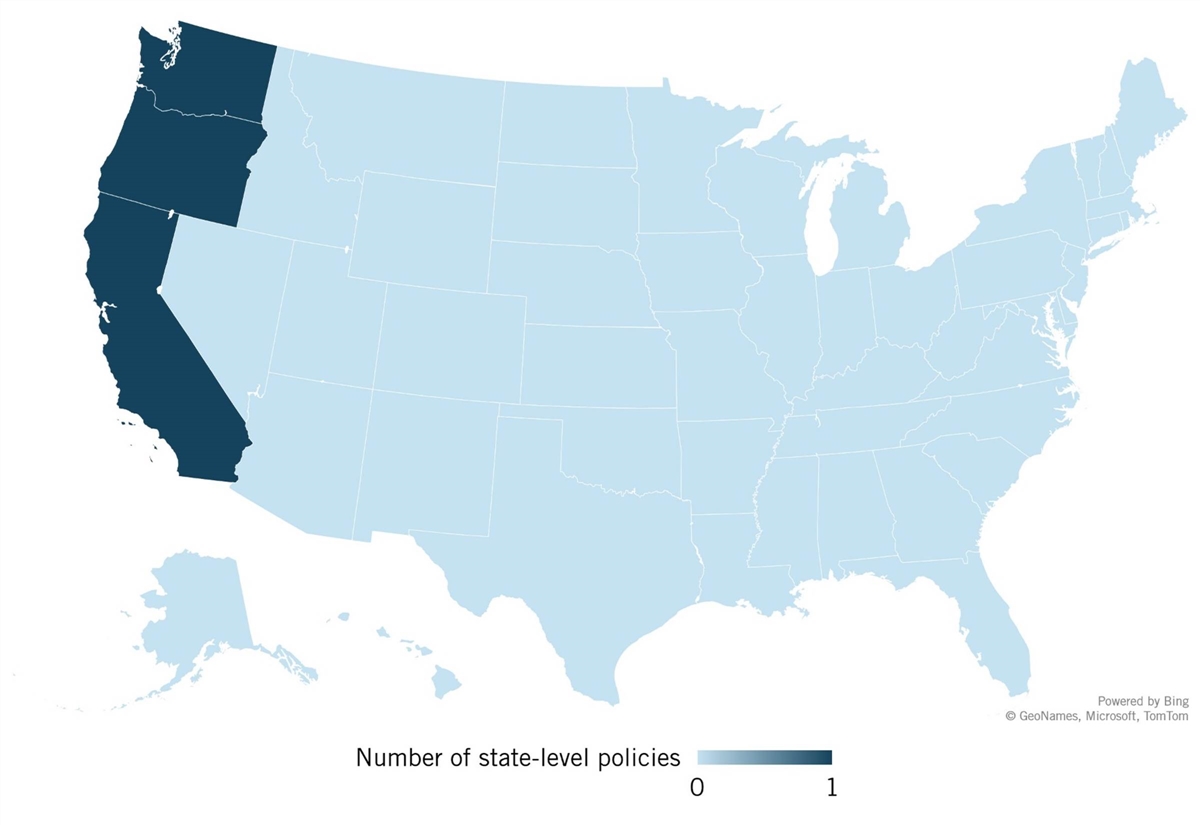

Right to Repair

Right to repair laws give consumers the right to repair products they own either themselves or with a third party. These laws are not exclusively a digital policy issue, as they can also apply to products such as automobiles and farm equipment. The digital policy aspect of right to repair comes into play when these laws apply to electronic devices or when products incorporate digital measures that limit repairs.

Many states have considered legislation that would create a right to repair for electronic devices, with three such bills passing into law in California, Minnesota, and New York.[69] Generally, these laws require manufacturers to make diagnostic and repair information, parts, and tools available to independent repair providers and product owners. There is no federal right to repair law for electronics or any other category of product as such, although the Magnuson-Moss Warranty Act, passed in 1975, states that any consumer product with a warranty cannot require consumers use only branded parts in conjunction with the product. These requirements are known as tie-in sales provisions, and their prohibition is one of the baselines for the right to repair argument.[70]

Figure 9: State-level policies on right to repair electronics as of February 2024

There are advantages to establishing a right to repair for electronics. First, it increases competition and consumer choice in the market of electronics repair. Consumers may still choose to take their electronic devices back to the original manufacturer for repairs, just as many consumers choose to take their automobiles back to the dealership that sold them the vehicle for repairs. A survey conducted in 2021 by Cox Automotive found that over one-third of consumers prefer dealership service centers over other alternatives.[71] This would also benefit consumers in cases where, currently, they cannot even take their electronics back to the original manufacturer for repairs because the manufacturer does not offer repair services.

However, because the law would require manufacturers to make the necessary information, parts, and tools available, consumers could also choose from a variety of third-party repair shops. If they have the skills, consumers may even choose to repair their devices themselves. This could reduce the cost of repair for many consumers. The right to repair could also have environmental benefits if more consumers choose to repair their devices rather than buying new ones.

Researchers from the University of Singapore and the University of California, Berkeley studied the potential impact of right to repair on pricing, consumer welfare, and the environment. They found that electronics manufacturers will likely respond to right to repair legislation by lowering the cost of new electronics to incentivize consumers to purchase new products rather than repair old ones. These reduced prices would benefit consumers but limit the potential environmental benefits of right to repair.[72]

Opponents of right to repair legislation cite security and privacy concerns, arguing that requiring manufacturers of electronic devices to make proprietary information publicly available would give hackers the keys to find and exploit vulnerabilities in those devices, though many security experts dispute these claims.[73] Opponents also argue that untrustworthy repair providers could access device owners’ personal data, although these same types of privacy and security violations can and do occur at the hands of authorized repair providers.[74]

The movement to establish a federal right to repair for electronics and other product categories reached the White House during the Biden administration, with President Joe Biden endorsing the right to repair in his Executive Order on Promoting Competition in 2021 and convening a roundtable on the subject in 2023.[75] Thus far, this has not translated into federal legislation, with the only right to repair bill currently facing Congress focusing on automotive repair rather than electronics.[76]

Right of Publicity

Right of publicity is an intellectual property (IP) protection that gives individuals the right to control the commercial use of their identity. IP was an issue in which the federal government intervened early to establish a common set of rules for the digital age. The Internet allows users to widely and rapidly disseminate content, including copyrighted content or the means to illegally access copyrighted content. This creates problems for copyright holders, content-based industries that heavily rely on copyright protections, and online services that allow third-party content sharing. Congress passed the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) in 1998, updating existing copyright law to reflect this new reality.

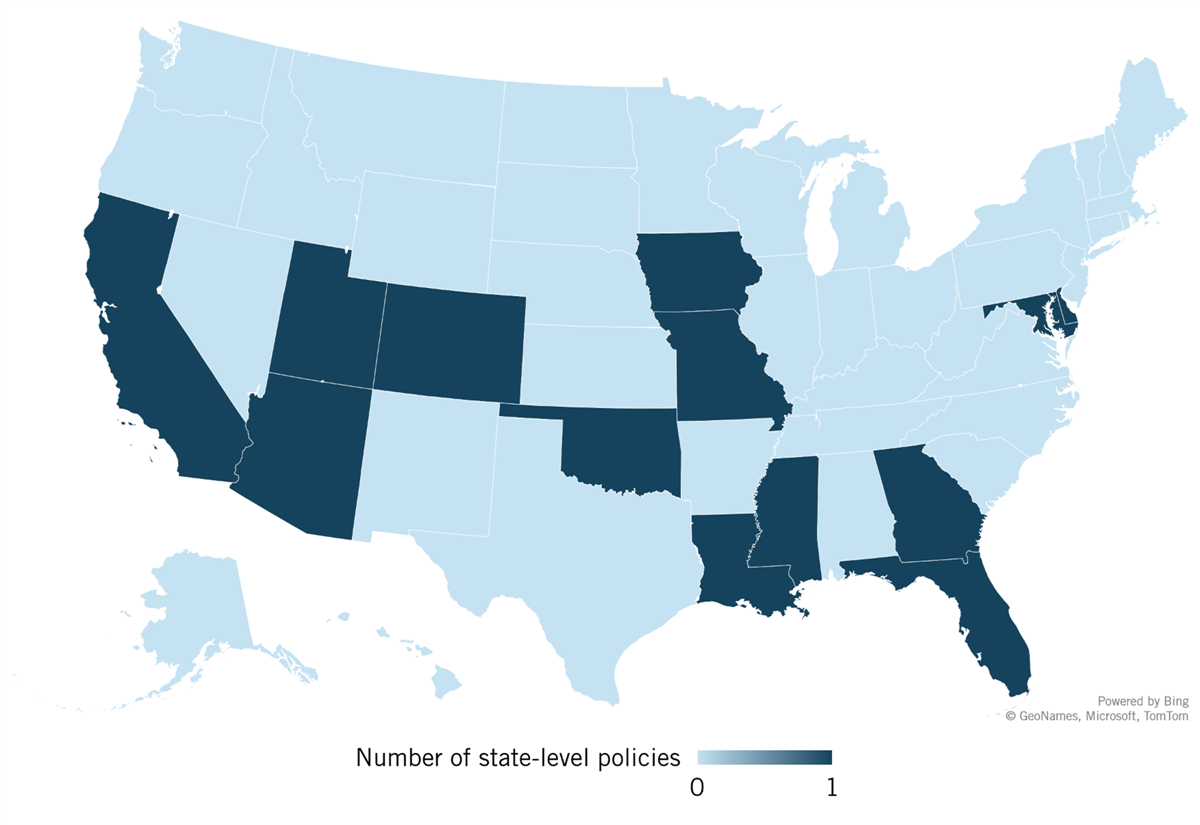

Figure 10: State-level policies on right of publicity as of February 2024

The DMCA makes it a crime to circumvent access controls or produce or disseminate the means to circumvent digital rights management (DRM) technologies. Access controls restrict access to computer systems to only authorized users, while DRM technologies restrict access to copyrighted works. The DMCA also establishes a safe harbor for online services separate from the liability protections in Section 230. In order to qualify for this safe harbor, online services must remove or block access to potentially infringing content when they receive a notice-and-takedown request from the copyright holder. The user who originally posted the potentially infringing content can then submit a counternotice if the content was not infringing.[77]

Federal preemption in copyright law dates back before the DMCA. Under the Copyright Act of 1909, federal copyright law protected published works and state laws protected unpublished works. Then, the Copyright Act of 1976 preempted all state copyright laws that fall within the scope of federal law and provide equivalent rights to those provided by federal law.[78] States still can and do maintain their own laws protecting IP so long as these laws fall outside the scope of federal law and do not conflict with it.

With the emergence of new technologies such as AI, policymakers face new IP challenges. AI raises questions such as whether and how AI-generated work should receive IP protection, whether AI text and data mining raises copyright concerns, and how to protect individuals from AI duplicating their likeness for commercial use. Several states have passed laws that address this last issue, creating a right of publicity. As of December 2023, 25 states have laws codifying a right of publicity, with some of these laws also establishing a postmortem right of publicity that applies to deceased individuals for a certain period of time after death.[79]

The principles behind a right of publicity date back long before AI, but have become increasingly relevant in the digital age due to threats posed by digital manipulation and deepfakes, leading Congress to consider establishing a federal right of publicity.[80] Not only would this ensure all Americans have the same right to control the commercial use of their identity, but it would have the added benefit of establishing the right of publicity as a federal IP right, exempting it from Section 230. In practice, this would mean if content infringing on an individual’s right of publicity—such as an AI-generated deepfake—that individual could submit a notice-and-takedown request to any online services on which the infringing content was posted or shared.

Importantly, a federal right of publicity should take free speech concerns into account, as federal copyright law currently does by allowing for fair use of copyrighted material under certain circumstances. For example, a federal right of publicity should not prevent the media from reporting on or depicting newsworthy events or matters of public interest or prevent content creators from engaging in satire, parody, or commentary about public figures.

A related challenge, also arising from the proliferation of AI, is nonconsensual pornography, colloquially known as revenge porn, using deepfakes. Deepfakes are AI-generated images, videos, or audio that portray an individual doing or saying something that never actually happened. Deepfake revenge porn portrays an individual in a sexual situation that never actually happened. As with all types of nonconsensual pornography, this can have devastating consequences for victims’ lives and livelihoods. There is currently no federal law criminalizing nonconsensual pornography, though such laws exist in 48 states and the District of Columbia and the Violence Against Women Act Reauthorization Act of 2022 allows victims of nonconsensual pornography to sue for damages in federal court.[81] Additionally, 16 states have laws addressing deepfakes.[82]

Net Neutrality

Net neutrality refers to the principle that Internet service providers (ISPs) must treat all online services equally, providing access at the same speed, under the same conditions, without blocking or preferencing. The concept has a contentious regulatory history in the United States, with regulations changing from one presidential administration to another.

Figure 11: State-level policies on net neutrality as of February 2024

Until 2015, the Internet was not regulated as a common carrier under Title II of the Communications Act. The term “common carrier” emerged in the context of transportation and was later applied to telecommunications, applying to a transportation service such as a railroad or a telecommunications service such as a telephone provider that makes its service available to the general public for a fee, as opposed to offering the services on a contract basis.[83] Telecommunications common carriers are subject to regulations laid out in the Communications Act of 1934, including nondiscrimination requirements.[84]

Pressure from the Obama White House led the FCC to reclassify broadband Internet as a telecommunications common carrier under Title II, ostensibly to ensure that ISPs didn’t engage in anti-consumer practices, such as blocking or throttling competitors, though these threats were only hypothetical.[85] When the FCC repealed those regulations during the Trump administration, advocates for net neutrality predicted that the blocking and throttling would finally begin, but instead, the Internet thrived.[86]

The same year the FCC’s repeal went into effect, California passed the California Internet Consumer Protection and Net Neutrality Act of 2018, a state-level net neutrality law that prohibits ISPs from blocking or throttling lawful traffic or accepting payment to prioritize traffic or zero-rate (provide access for free) certain content, among other provisions.[87] The Department of Justice (DOJ) sued California the same day the governor signed the Net Neutrality Act into law, arguing that states do not have jurisdiction over the Internet.[88] The DOJ dropped its suit in 2021, during the Biden administration, with then-acting FCC chairwoman Jessica Rosenworcel, who supported the FCC’s Obama-era regulations and opposed the Trump-era repeal, praising this decision.[89] A group of trade associations representing ISPs also challenged the Net Neutrality Act before dropping the suit in 2022 after failing three times to get a preliminary injunction against the law.[90]

California’s net neutrality law had a tangible negative impact on consumers. As a result of the law, AT&T had to stop offering certain data features to consumers free of charge. The law banned “sponsored data” services, which allow companies to pay for the data usage of their customers who are also customers of a particular wireless provider: in this case, AT&T. Prior to the law, AT&T customers could browse and stream content from these sponsors without dipping into their monthly data allowance. Due to the difficulty of complying with different regulations in different states, this also impacted AT&T customers outside California.[91]

Several other states followed California in passing net neutrality laws of their own, including Colorado, Maine, New Jersey, Oregon, Vermont, and Washington. The FCC has also indicated it may reinstate net neutrality at the federal level, adopting a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking on the subject in October 2023.[92] This regulatory back and forth and state-by-state approach creates uncertainty for businesses, highlighting the need for federal net neutrality legislation. Congress has considered a few net neutrality bills since the FCC’s repeal, but these bills did not make it out of committee.[93]

Digital Identification

As Americans move more of their everyday activities online, they increasingly encounter situations where they need to prove their identity or verify some aspect of their identity, such as their age, via the Internet. This typically involves tediously uploading a photo of their physical ID, as well as sometimes additional steps to prove the ID belongs to the individual who uploaded it, such as uploading a current image of their face to compare to the face displayed on the ID.

Digital forms of identification would streamline the process of online identity verification, enable more secure online applications and transactions, facilitate e-government services, and reduce identity theft and fraud. If designed right, digital IDs would also increase privacy for consumers by allowing them to only share necessary information instead of all the information their full ID provides. For example, a consumer buying age-restricted products or interacting with age-restricted content could verify that they are over a certain age without providing their exact date of birth, full name, and address. In the United States, there is currently no federal initiative to offer digital forms of identification, leaving the states to take up the effort in the form of mobile driver’s licenses (mDLs), accessible via an app on an individual’s phone. As of 2023, 12 states offer mDLs and 19 states, Puerto Rico, and the District of Columbia have announced plans to offer mDLs. Louisiana was the first state to launch an mDL in 2018, and as of 2023, 66 percent of eligible adults have an mDL in the state.[94] More than 25 airports accept mDLs as a valid form of identification.[95]

Figure 12: State-level policies on digital identification as of February 2024

The state-by-state approach to digital IDs is further complicated by the different platforms each state uses to provide these IDs. Some states use Apple Wallet, which is not available to users of non-Apple devices. Others use Mobile ID by Idemia, a company that provides identity-related security services. Utah uses yet another provider, GET Mobile ID, and Florida has its own platform called Smart ID.[96] This segmented approach poses challenges for businesses that need to verify consumers’ identities in multiple states, as well as consumers traveling or moving between different states.

At the federal level, the National Institute of Standards and Technology first published its Digital Identity Guidelines, which outline technical requirements for federal agencies implementing digital ID services, in 2004, drafting its most recent update to the guidelines in 2023.[97] The Obama administration published a National Strategy for Trusted Identities in Cyberspace (NSTIC) in 2011, establishing guiding principles, goals, and objectives for creating digital identity solutions.[98] NSTIC ultimately led to the creation of Login.gov, a single sign-on service for users to securely access services from federal government agencies online, with little progress beyond this, as subsequent administrations have not maintained the same focus on digital identity verification.

Members of Congress have repeatedly reintroduced bipartisan legislation to create a framework for deploying a digital ID system. The Improving Digital Identity Act would establish a task force of representatives from federal agencies and state and local governments to develop an interoperable, government-wide framework for securely issuing and validating digital IDs. It would also offer grants for states to implement digital IDs.[99]

Recommendations

In many areas of digital policy, states have passed or considered legislation that imposes barriers to innovation. The cost of compliance is high, the process of compliance is needlessly complex, and consumers’ rights vary from state to state. Federal preemption on these issues would reduce costs to businesses, reduce confusion for businesses and consumers, and make progress toward a U.S. digital single market.

Congress should:

▪ form a bipartisan U.S. Digital Single Market Commission to draft legislation for areas for federal preemption, focusing on digital issues that affect interstate commerce, such as e-commerce regulation, digital taxation, and children’s online safety;[100]

▪ pass comprehensive federal data privacy and security legislation that preempts state laws, including AI and biometric privacy laws and data breach notification laws, and take a light-touch approach that addresses actual privacy harms while reducing costs that hinder productivity and innovation;[101]

▪ pass a moratorium on state children’s online safety legislation with a five-year sunset clause if Congress does not pass federal legislation based on recommendations from the U.S. Digital Single Market Commission;

▪ take steps to enable noninvasive online age verification by providing funding for the research and development of age estimation technology using AI and mandating states implement electronic forms of identification as part of obtaining a driver’s license or other form of ID;[102]

▪ update the PITFA to ban taxes on wireless services and discriminatory taxes on digital goods and services that do not have a physical component;

▪ pass legislation instructing the Alcohol and Tobacco Products Tax and Trade Bureau, FTC, and FDA to establish uniform regulations for age-restricted or medical products purchased online, which should include streamlined rules for shipping alcoholic beverages directly to consumers, a federal requirement for eye doctors to include patients’ pupillary distance on prescriptions, and a federal requirement for veterinarians to provide prescriptions upon request without extra fees;

▪ update the UETA and ESIGN Act to require states to recognize the legality and enforceability of records, signatures, and contracts secured over a blockchain;

▪ preempt state right to repair laws by passing a consistent right to repair standard for electronics at the federal level;

▪ establish a federal right of publicity that gives individuals the right to control the commercial use of their identity while allowing for fair use, such as reporting on or depicting newsworthy events or matters of public interest;

▪ outlaw the nonconsensual distribution of sexually explicit images, or nonconsensual pornography, including deepfakes that duplicate individuals’ likenesses in sexually explicit images, and also create a special unit in the FBI to provide immediate assistance to victims of nonconsensual pornography and deepfake nonconsensual pornography;

▪ pass net neutrality legislation that does not regulate broadband Internet as a telecommunications common carrier under Title II of the Communications Act and instead codifies widely agreed-upon Internet protections and gives the FCC reasonable jurisdiction to enforce open Internet rules;[103] and

▪ pass the Improving Digital Identity Act to create a framework for deploying a digital ID system at the federal, state, and local level.

▪ At the same time, states should continue their ongoing work of streamlining the taxation of e-commerce to create common definitions, rules, and simplified tax rate structures under the SSUTA, with the goal of all states signing on.

About the Author

Ashley Johnson (@ashleyjnsn) is a senior policy analyst at ITIF. She researches and writes about Internet policy issues such as privacy, security, and platform regulation. She was previously at Software.org: the BSA Foundation and holds a master’s degree in security policy from The George Washington University and a bachelor’s degree in sociology from Brigham Young University.

About ITIF

The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) is an independent 501(c)(3) nonprofit, nonpartisan research and educational institute that has been recognized repeatedly as the world’s leading think tank for science and technology policy. Its mission is to formulate, evaluate, and promote policy solutions that accelerate innovation and boost productivity to spur growth, opportunity, and progress. For more information, visit itif.org/about.

Endnotes

[1]. U.S. Const. Article I, Section 8, Clause 3.

[2]. U.S. Const. Amendment 10.

[3]. New State Ice Co. v. Liebmann, 285 U.S. 262 (1932).

[4]. Hayley Tsukayama, “Federal Preemption of State Privacy Law Hurts Everyone,” Electronic Frontier Foundation, July 28, 2022, https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2022/07/federal-preemption-state-privacy-law-hurts-everyone.

[5]. Andrew Folks, “US State Privacy Legislation Tracker,” International Association of Privacy Professionals, updated September 15, 2023, https://iapp.org/resources/article/us-state-privacy-legislation-tracker/.

[6]. Daniel Castro and Ashley Johnson, “Why Can’t Congress Pass Federal Data Privacy Legislation? Blame California” (ITIF, December 13, 2019), https://itif.org/publications/2019/12/13/why-cant-congress-pass-federal-data-privacy-legislation-blame-california/.

[7]. “State government trifectas,” Ballotpedia, accessed September 22, 2023, https://ballotpedia.org/State_government_trifectas.

[8]. “Party Government Since 1857,” U.S. House of Representatives, accessed September 22, 2023, https://history.house.gov/Institution/Presidents-Coinciding/Party-Government/.

[9]. Alan McQuinn and Daniel Castro, “The Case for a U.S. Digital Single Market and Why Federal

Preemption Is Key” (ITIF, October 2019), https://itif.org/publications/2019/10/07/case-us-digital-single-market-and-why-federal-preemption-key/.

[10]. “EU Digital Strategy,” EU4Digital, accessed December 8, 2023, https://eufordigital.eu/discover-eu/eu-digital-strategy/.

[11]. Robert D. Atkinson and Stephen Ezell, “Promoting European Growth, Productivity, and Competitiveness By Taking Advantage of the Next Digital Technology Wave” (ITIF, March 2019), http://www2.itif.org/2019-europe-digital-age-a4.pdf.

[12]. “GDPR Countries 2023,” GDPR Advisor, accessed December 5, 2023, https://www.gdpradvisor.co.uk/gdpr-countries.

[13]. Laura Jehl and Alan Friel, “CCPA and GDPR Comparison Chart” (Thomson Reuters, 2018), https://iapp.org/media/pdf/resource_center/CCPA_GDPR_Chart_PracticalLaw_2019.pdf.

[14]. Andrew Folks, “US State Privacy Legislation Tracker,” International Association of Privacy Professionals, updated November 17, 2023, https://iapp.org/resources/article/us-state-privacy-legislation-tracker/.

[15]. Daniel Castro and Gillian Diebold, “The Looming Cost of a Patchwork of State Privacy Laws” (ITIF, January 2022), https://itif.org/publications/2022/01/24/looming-cost-patchwork-state-privacy-laws/.

[16]. Amy de La Lama and Lauren J. Caisman, “U.S. biometric laws & pending legislation tracker,” Bryan Cave Leighton Paisner, June 2, 2023, https://www.bclplaw.com/en-US/events-insights-news/us-biometric-laws-and-pending-legislation-tracker.html.

[17]. Castro and Diebold, “The Looming Cost.”

[18]. Pub. L. No. 104-191, 110 Stat. 1936 (1996).

[19]. Pub. L. No. 106-102, 113 Stat. 1338 (1999).

[20]. 15 US.C. § 6501-6506 (1998).

[21]. Ashley Johnson, “Three Bills Show Remaining Divisions in Attempt to Reach a Compromise on Federal Data Privacy Legislation” (ITIF, June 17, 2022), https://itif.org/publications/2022/06/17/bills-show-remaining-divisions-on-federal-data-privacy-legislation/.

[22]. “Security Breach Notification Laws,” National Conference of State Legislatures, updated January 17, 2022, https://www.ncsl.org/technology-and-communication/security-breach-notification-laws.

[23]. Daniel Castro, “States Should Revisit Their Data Breach Laws,” Government Technology, June 4, 2018, https://www.govtech.com/policy/states-should-revisit-their-data-breach-laws.html.

[24]. “Breach Notification Rule,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, updated July 26, 2013, https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/breach-notification/index.html.

[25]. “Complying with FTC’s Health Breach Notification Rule,” Federal Trade Commission, updated January 2022, https://www.ftc.gov/business-guidance/resources/complying-ftcs-health-breach-notification-rule-0.

[26]. Katie Gorscak, “FCC Adopts Updated Data Breach Notification Rules to Protect Consumers,” FCC, December 13, 2023, https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/DOC-399090A1.pdf.

[27]. “SEC Adopts Rules on Cyberseurity Risk Management, Strategy, Governance, and Incident Disclosure by Public Companies,” SEC, July 26, 2023, https://www.sec.gov/news/press-release/2023-139.

[28]. “H.R.1770 - Data Security and Breach Notification Act of 2015,” Congress.gov, accessed December 15, 2023, https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/1770; “S.744 - Data Care Act of 2023,” Congress.gov, accessed December 15, 2023, https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/senate-bill/744.

[29]. “AB-2273 The California Age-Appropriate Design Code Act,” California Legislative Information, updated November 18, 2022, https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billCompareClient.xhtml?bill_id=202120220AB2273&showamends=false.

[30]. Jenna Zhang et al., “State, Federal, and Global Developments in Children’s Privacy, Q1 2023,” Inside Privacy, April 2, 2023, https://www.insideprivacy.com/childrens-privacy/state-federal-and-global-developments-in-childrens-privacy-q1-2023/.

[31]. NetChoice, LLC v. Bonta, No. 22-CV-09961-BLF (N.D. Cal. 2023).

[32]. “Age Verification Bill Tracker,” Free Speech Coalition Action Center, accessed November 30, 2023, https://action.freespeechcoalition.com/age-verification-bills/.

[33]. Ashley Johnson, “Lacking a Federal Standard, States Try and Fail to Solve Problems Faced by Kids Online” (ITIF, November 17, 2023), https://itif.org/publications/2023/11/17/lacking-a-federal-standard-states-try-and-fail-to-solve-problems-faced-by-kids-online/.

[34]. NetChoice, LLC v. Griffin, No. 5:2023-CV-05105 (W.D. Ark. 2023).

[35]. NetChoice, LLC v. Reyes, No. 2:2023-CV-00911 (D. Utah 2023); NetChoice, LLC v. Yost, No. 2:2024-CV-00047 (S.D. Ohio 2024).

[36]. Free Speech Coalition, Inc. v. LeBlanc, No. 2:2023-CV-02123 (E.D. La. 2023); Free Speech Coalition, Inc. v. Paxton, No. 23-50627 (5th Cir. 2023); Free Speech Coalition, Inc. v. Anderson, No. 2:2023-CV-00287 (D. Utah, 2023).

[37]. Vanessa M. Perez, “Americans With Photo ID: A Breakdown of Demographic Characteristics” (Project Vote, February 2015), https://www.projectvote.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/AMERICANS-WITH-PHOTO-ID-Research-Memo-February-2015.pdf.

[38]. Reno v. American Civil Liberties Union, 521 US 844 (1997).

[39]. “S.1207 - EARN IT Act of 2023,” Congress.gov, accessed November 30, 2023, https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/senate-bill/1207/text.

[40]. “S.1409 - Kids Online Safety Act,” Congress.gov, accessed November 30, 2023, https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/senate-bill/1409/text.

[41]. “S. 1199 - STOP CSAM Act of 2023,” Congress.gov, accessed November 30, 2023, https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/senate-bill/1199/text.

[42]. “S.1418 - Children and Teens’ Online Privacy Protection Act,” Congress.gov, accessed January 9, 2024, https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/senate-bill/1418/text.

[43]. Ashley Johnson and Daniel Castro, “The EARN IT Act Is a Threat to Privacy, Free Speech, and the Internet Economy” (ITIF, July 10, 2020), https://itif.org/publications/2020/07/10/earn-it-act-threat-privacy-free-speech-and-internet-economy/; Ashley Johnson, “Stopping Child Sexual Abuse Online Should Start With Law Enforcement” (ITIF, May 10, 2023), https://itif.org/publications/2023/05/10/stopping-child-sexual-abuse-online-should-start-with-law-enforcement/.

[44]. Emma Llansó and Caitlin Vogus, “CDT Leads Broad Civil Society Coalition Urging Senate to Drop EARN IT Act,” Center for Democracy & Technology, May 2, 2023, https://cdt.org/insights/cdt-leads-broad-civil-society-coalition-urging-senate-to-drop-earn-it-act/.

[45]. 47 US.C. § 230 (1996).

[46]. Ashley Johnson and Daniel Castro, “Overview of Section 230: What It Is, Why It Was Created, and What It Has Achieved” (ITIF, February 2021), https://itif.org/publications/2021/02/22/overview-section-230-what-it-why-it-was-created-and-what-it-has-achieved/.

[47]. 47 US.C. § 230 (1996).

[48]. Ashley Johnson and Daniel Castro, “Fact-Checking the Critiques of Section 230: What Are the Real Problems?” (ITIF, February 2021), https://itif.org/publications/2021/02/22/fact-checking-critiques-section-230-what-are-real-problems/.

[49]. CCIA, “State Content Moderation Landscape” (CCIA, November 2022), https://ccianet.org/library/state-content-moderation-landscape/.

[50]. “SB 7072: Social Media Platforms,” The Florida Senate, accessed November 29, 2023, https://www.flsenate.gov/Session/Bill/2021/7072/?Tab=BillText.

[51]. “HB 20,” Texas Legislature Online, accessed November 29, 2023, https://capitol.texas.gov/BillLookup/Text.aspx?LegSess=872&Bill=HB20.

[52]. NetChoice, LLC v. Attorney General, No. 21-12355 (11th Cir. 2022); NetChoice, LLC v. Paxton, 49 F.4th 439 (5th Cir. 2022).

[53]. Ashley Johnson, “The Supreme Court Could Save the Internet (Again)” (ITIF, October 5, 2023), https://itif.org/publications/2023/10/05/the-supreme-court-could-save-the-internet-again/.

[54]. Susannah Fox and Lee Rainie, “Part 1: How the internet has woven itself into American life,” Pew Research Center, February 27, 2014, https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2014/02/27/part-1-how-the-internet-has-woven-itself-into-american-life/.

[55]. 47 US.C. § 151 (1998).

[56]. Karl Nicolas, “US Congress passes permanent Internet Tax Freedom Act with a 2020 sunset date for taxes imposed by grandfathered states,” Ernst & Young, February 11, 2016, https://taxnews.ey.com/news/2016-0299-us-congress-passes-permanent-internet-tax-freedom-act-with-a-2020-sunset-date-for-taxes-imposed-by-grandfathered-states.

[57]. John B. Horrigan, “Part 1. Trends in Online Shopping,” Pew Research Center, February 13, 2008, https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2008/02/13/part-1-trends-in-online-shopping/.

[58]. Jungle Scout, “Consumer Trends Report: Q3 2023” (Jungle Scout, 2023), https://www.junglescout.com/consumer-trends/2023-q3/.

[59]. Congressional Research Service, “Internet Tax Freedom Act and Federal Preemption” (Congressional Research Service, October 2021), https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF11947.

[60]. Emily A. Vogels, “Digital divide persists even as Americans with lower incomes make gains in tech adoption,” Pew Research Center, June 22, 2021, https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2021/06/22/digital-divide-persists-even-as-americans-with-lower-incomes-make-gains-in-tech-adoption/.

[61]. “About Us,” Streamlined Sales Tax Governing Board, accessed December 1, 2023, https://www.streamlinedsalestax.org/about-us/about-sstgb.

[62]. “Alcohol Delivery Laws: Which States Allow Online Alcohol Purchase?” TIPS, accessed December 6, 2023, https://www.gettips.com/blog/alcohol-delivery-laws.

[63]. “Complying with the Eyeglass Rule,” Federal Trade Commission, updated April 2023, https://www.ftc.gov/business-guidance/resources/complying-eyeglass-rule.

[64]. “Need Pet Meds? Protect Yourself and Your Pet—Be Website A.W.A.R.E.,” Food and Drug Administration, updated October 21, 2022, https://www.fda.gov/animal-veterinary/animal-health-literacy/need-pet-meds-protect-yourself-and-your-pet-be-website-aware.

[65]. “Prescriptions and pharmacies: FAQs for pet owners,” American Veterinary Medical Association, accessed December 7, 2023, https://www.avma.org/resources-tools/animal-health-and-welfare/animal-health/pharmacy/prescriptions-and-pharmacies-faq-pet-owner.

[66]. Claire Rosston and Gabriel Hamilton, “Charging Fees for Online Pet Prescriptions: Is it Illegal? Is it Bad Business?” Holland & Hart, March 28, 2023, https://www.hollandhart.com/compensation-for-preparing-pet-prescriptions-for-online-pharmaciesis-it-illegal-is-it-bad-business.

[67]. “Electronic Signature Laws & Regulations - United States,” Adobe, updated September 8, 2022, https://helpx.adobe.com/legal/esignatures/regulations/united-states.html.

[68]. Ibid.

[69]. “Right to Repair 2023 Legislation,” National Conference of State Legislation, updated November 1, 2023, https://www.ncsl.org/technology-and-communication/right-to-repair-2023-legislation.