Building Canadian Start-Ups Through Global Experience

There is a small but growing view in Canadian technology policy circles that Canada should reduce the number of foreign tech firms and rely almost exclusively on domestic firms, especially start-ups. This would be a critical mistake, partly because, as is true in so many nations, multinationals provide important knowledge transfers and training.

It turns out that the founders of many of Canada’s most successful tech firms gained critical experience working for foreign multinational tech companies. These firms, from U.S. giants like Google and Microsoft to other global players, are significant training grounds for Canadian entrepreneurial talent.

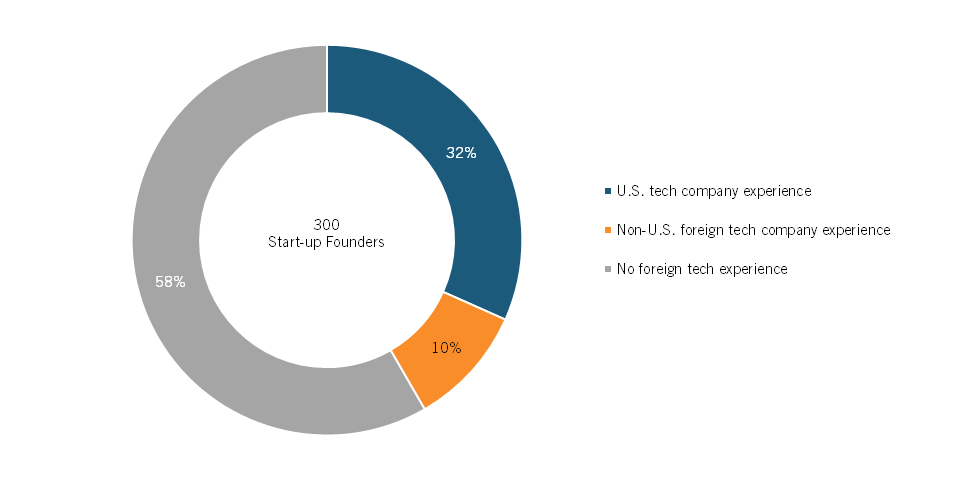

A LinkedIn review of 300 randomly selected tech start-up founders in Canada found that 41 percent had previously worked for foreign multinational tech companies in Canada. Ninety-five had worked for U.S. tech companies, while 30 had similar experiences with non-U.S. foreign tech companies. More than a quarter of the remaining 175 founders had experience working for multinational consulting firms or had the majority of their prior work experience outside of Canada. The experience of working for these multinational tech companies provides a foundation for launching successful Canadian tech start-ups. Indeed, the founders of many of Canada’s most well-known tech scaleups, like 1Password, Wattpad, and Ritual, drew on their experiences working in Canada for foreign tech companies.

Figure 1: Randomly selected sample of 300 Canadian start-up founders on LinkedIn

While working for a foreign tech firm is certainly not the only pathway to success, the resources, learning, and exposure offered by these firms often provide individuals with critical skills for kickstarting their own ventures. For instance, their prior experience at global tech firms likely provides these founders with the opportunity to pick up best practices in software development, project management, and operations that are all directly transferable to their new entrepreneurial journey. On top of that, as foreign tech firms tend to have highly competitive salaries and benefits packages, founders can better reduce their personal financial risk when taking the leap. Finally, exposure to global technology trends and awareness of unfulfilled niches helps founders develop companies and products that are better able to solve problems existing in wider markets rather than exclusively domestic markets.

Some may argue that these founders have foreign tech experience not because it drives their entrepreneurial success, but because many tech jobs in Canada are with foreign multinationals—suggesting that without these global firms in Canada, these individuals would simply take on other tech roles within the country. However, Canada has relatively few domestic tech firms that compete at the same global scale as the foreign multinational tech companies for which these founders worked. In their hypothetical absence, it is not guaranteed that these founders would have had similar access to resources, advanced technologies, or international exposure. While the dominance of foreign firms may explain the employment pipeline, they are instrumental in equipping founders with skills and insights that smaller or less global domestic companies might struggle to provide.

If Canada were to follow through on the destructive advice of domestic techno-economic nationalists by discriminating against foreign tech companies and reducing the role that these companies play in the Canadian economy, many of these jobs could dry up. Foreign multinational companies may be convenient scapegoats for why Canadian tech companies have seen little large-scale success on the global stage, but their presence is not a negative. These firms are complementary and additive to the domestic tech economy. With companies like Google, Ericsson, and Microsoft all having invested hundreds of millions into Canada’s economy in just the last few years and employing tens of thousands of Canadians, it is an immense mistake to discount the role that foreign tech companies play: employment, knowledge spillovers, and technology advancement.

Canada’s tech ecosystem benefits from the presence of foreign multinational companies, not only through job creation and investment but also by serving as a training ground for future entrepreneurs. Their role in equipping Canadian founders with global skills, networks, and perspectives is critical. Instead of viewing foreign tech companies as competitors to domestic innovation, Canada must embrace their complementary role in fostering a vibrant, interconnected tech ecosystem. Ultimately, the key lies in striking a balance—leveraging the resources and opportunities these companies bring while supporting and building up Canadian companies that can compete on a global stage.