Hi-Tech Diversity Is a Societal Goal, Not an Industry Scandal

Each issue in this Defending Digital series counters a prominent information technology industry critique. In previous installments, we have argued that complaints about the loss of individual privacy, embedded AI bias, excessive Big Tech power, the spread of misinformation, and similar charges tend to be either speculative or exaggerated.[1] While the digital world does create new societal risks, the balance is clear. Information technology is an essential source of American progress. There is much less need for government intervention and/or regulation than is often claimed.

In this edition, we address the charge that the digital world lacks sufficient diversity. This is a different sort of accusation. Unlike the other topics in this series, information technology does not create a major new set of issues. Instead, the technology industry faces the same set of diversity challenges that every industry has faced in recent decades: developing a more racially balanced workforce; welcoming the advances of working women; openly supporting the LGBTQ community; increasing accessibility in the workplace; treating older and younger employees more even-handedly; and ridding itself of all forms of religious discrimination.

These six diversity challenges have long been faced by “the professions”—medicine, law, architecture, engineering, accounting, investing, journalism, academia, government, and other fields that require specialized education and training. By comparing the dynamics within these sectors to that of the information technology profession, we can develop a more objective analysis of the state of diversity within the IT industry today. We will see that three areas—race, gender, and age—receive most of the criticism, often excessively. In contrast, the digital world’s acceptance of diverse gender orientations, support for the disabled, and religious tolerance are all above average, and thus go largely unmentioned.

Outdated Racial Views

It’s easy to see where the idea that the digital field is overly white came from. The mainframe and minicomputer eras were created and led almost exclusively by white males—Thomas Watson Sr. and Jr., Gene Amdahl, Seymour Cray, Ross Perot, Gordon Moore, Andy Grove, Ken Olsen, and so on (with An Wang a notable exception). But most of these gentlemen could walk down the street and go unrecognized. The faces that entrenched the white male meme emerged during the consumer phase of the IT industry—Steve Jobs, Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos, Mark Zuckerberg, and Elon Musk, along with many other lesser-known entrepreneurs and technologists.

But in the 21st century the face of the industry has changed. Today, the CEOs of Microsoft, IBM, Google, Twitter, Adobe, Global Foundries, Sandisk, Micron, and NetApp are all of Indian heritage. The next level of management in Silicon Valley is even more India-intensive, especially the chief technology officer role. Similarly, two of the world’s most important semiconductor companies were founded by Taiwanese-Americans. Morris Chang spent 25 years at Texas Instruments before founding Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corp. (TSMC), now the world’s largest chip manufacturer. Jensen Huang moved to America from Taiwan when he was nine years old. After graduating from Stanford and working in Silicon Valley, he co-founded Nvidia, the leading provider of specialized AI chips. Then there is Eric Yuan—born in China and now a U.S. citizen—who founded Zoom after many years working at Webex and Cisco.

The importance of Indian and Asian technology professionals is even greater when the IT industry is viewed from a global supply chain perspective. Millions of Chinese citizens manufacture most of the computers, smartphones, and networking equipment we use, just as millions of Indian nationals do the back-office IT work that keeps large U.S. multinationals operating 24*7. Chinese, Korean, Taiwanese, Japanese, and Indian firms rival the U.S.-based tech giants in many areas. The heavy presence of East Asian and Indian students and professors at America’s most elite STEM universities is also striking, to the point of worrisome dependence. This global ecosystem of Asian and Indian students, teachers, entrepreneurs, executives, and mentors gets stronger every year.

Given all of this, the claim that the 21st century IT industry is dominated by white people is not just wrong; it’s absurd. So why does this outdated stereotype persist? Basically, it lives on as a way of saying that the number of African-Americans and Hispanic-Americans in technology is much lower than their share of the overall population, without having to say that there are “too many Asians.” Harvard University is also trying desperately to avoid saying this in its affirmative action case.[2]

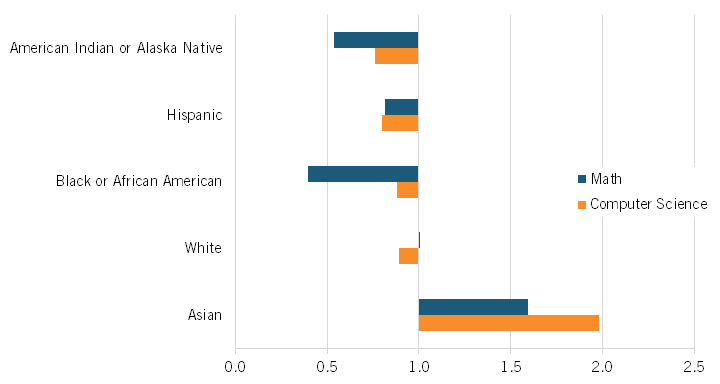

But as the figure below shows, Asians are overrepresented in Computer Science and Engineering degrees, as they are the only racial group that has a higher share of STEM degrees than their share of all U.S. degrees. Indeed, a key message of this chart is that, other than Asians (which here includes India), every race is under-represented in tech, including Whites. This reality is most visible at America’s leading universities. For example, a 2020 Stanford study showed that the share of white students in the school’s Computer Sciences program was just 34 percent, with “South and East Asia” over 50 percent.[3] Like Whites, Black and Hispanic populations are also under-represented, but in numbers similar to those in medicine, architecture, and other sciences.[4] Obviously, these low numbers make it harder for companies needing STEM workers to hire qualified African-Americans, Hispanics, and Native Americans.

Table 1: Ratio of STEM BS degrees to total BS degrees by race and ethnicity[5]

In short, the biggest racial story in the 21st century technology industry is not White dominance; it’s the dramatic rise of India and East Asia in virtually every STEM-based field. Importantly, there is little doubt about how this remarkable progress has been achieved. It wasn’t through quotas, targets, diversity outreach programs, or any form of preferential treatment. It was done through rigorous schools, hard study, intense merit-based competition, cultures that greatly value technical education, and national governments that recognize that a strong STEM-trained workforce is a high societal priority. Taken together, these efforts have overcome the deep prejudices that many Asian and Indian Americans have often faced.

Why Still Male?

The modern feminist movement emerged during the 1960s, and in the ensuing decades the economic progress of women has been unlike anything seen in human history. Whether we are looking at science, medicine, law, investing, accounting, architecture, academia, or journalism, the pattern has been the same. All of these fields were once almost entirely male, with women actively discouraged from even considering such careers. When women weren’t being barred outright, they were discriminated against, marginalized, underpaid, under-appreciated, denied promotions, expected to perform secretarial/administrative functions and often sexually harassed. From Wall Street to academia to the courtrooms and the major media, there are countless horror stories in every field and from every decade.

While these problems have not entirely gone away, the progress has been extraordinary. In U.S. graduate schools today, women outnumber men in medicine, law, journalism, teaching, and accounting. The gains in government and politics are also obvious for all to see. As the gender balance within a profession becomes more equal, the bad behavior of the past becomes less tolerable and harder to cover up. Over time, the students of today become the leaders of tomorrow, and supporting networks naturally grow. Eventually, leading businesses and institutions learn to accept the obvious: that many of their customers—especially female customers—strongly prefer female doctors, lawyers, teachers, journalists, or advisers. Looking ahead, a still-increasing wave of female talent is transforming many professions to the point where men may soon become a distinct minority.

These changes have clearly altered the face of society. But for our purposes the key question is how this extraordinary progress has been achieved. As with race, the advancement of women hasn’t been led by government programs and affirmative actions, and it certainly hasn’t been led by a suddenly enlightened male population. Once again, it was achieved via the education, skills, credentials, hard work, ambition, and perseverance needed to overcome entrenched barriers and stereotypes. In this sense, the gains of Indian and Asian professionals in STEM fields and the progress of women in non-STEM professions are remarkably similar.

But within the computer industry, the story is different, with male computer scientists and engineers still outnumbering females by roughly 4:1.[6] Why is this? There are two main theories, one at an educational level and one at an industry level.

From an educational perspective, there is the so-called pipeline theory—the belief that the share of women in high-tech leadership positions will over time tend to mirror the share of women in advanced STEM programs at leading universities. The evidence here is compelling. According to the National Science Foundation, in 2018 women accounted for just 22 percent of computer science doctorates, 32 percent of master’s degrees, and 20 percent of bachelor’s degrees. The numbers are similarly low for engineering, math, and statistics. In contrast, NSF reports that, “In biological sciences, women received over 60% of bachelor’s and master’s degrees, and over half of the doctoral degrees. Similarly, in the biopharma industry women STEM workers outnumber male ones, while in agricultural sciences, women earned over half of the bachelor’s and master’s degrees and 47.5% of doctorates.”[7]

Despite this data, many people bristle at the pipeline argument, even though it has also been the pattern in other professional fields. But, even if you accept the pipeline reality, this begs the question of why so many women choose to study fields other than IT. Some people suggest that women tend to find the heads-down, screen-oriented nature of many hi-tech activities less appealing than other forms of professional work that involve more human interaction. Others emphasize the lack of mentors, role models, and supporting networks, as well as gender-based cultural expectations and similar stereotypes. The debate continues.

At an industry level, the tech sector is often accused of being less welcoming to women than other professional fields. But as noted above, very strong resistance has been a shameful part of every industry’s history. If anything, the tech industry should be more welcoming as it tends to have younger workers, less steeped in the patriarchies of the past. Supporters of the tech is less welcoming theory sometimes counter with the stereotype that tech people are more socially awkward and thus are less comfortable with women in leadership positions. Maybe. But the number of organizations, initiatives, sponsorships, and awards supporting women in IT has never been higher. Consider the excitement that built up around Elizabeth Holmes and Theranos, which demonstrated that the world was keen—it turned out too keen—to celebrate what might have been the first female Steve Jobs. Most importantly, it’s not as if the demand for female STEM talent is not there; many companies would like to hire more women in these roles and have active efforts to do so. But given the relatively small talent pool, the competition can be fierce.

Although the root causes of the relatively low participation rate of women in many STEM fields are not fully understood and agreed upon, the lack of a strong and steady talent pipeline remains. This means that the low representation of women in IT starts well before anyone is actually employed in the technology industry. It also means that the demand for female technical talent is still greater than the supply. If the total population of women within computer science and engineering departments starts to rival men at America’s leading universities, greater professional equality will almost surely follow. It has ever been thus.

Predictable Ageism

Although not as high-profile a topic as racial and gender discrimination, Silicon Valley has long been accused of age discrimination, and the media is full of stories of people using Botox, dying their hair, and hiding their age on their LinkedIn profiles to appear more youthful. Although the data is sketchy, by most accounts the average tech worker is five to seven years younger than the average non-tech worker.[8] But is it really surprising that older industries such as banking, insurance, manufacturing, and agriculture would tend to have older workers? Of course not.

The most iconic personal computer companies were created by very young men. Bill Gates was 19, Steve Jobs 21, and Michael Dell 18 when they founded Microsoft, Apple, and Dell. Building giant companies at such a young age had never happened in any industry, even in hi-tech. For example, Ken Olsen was 31 when he founded Digital Equipment Corporation, as was An Wang when he started Wang Laboratories. Ross Perot was 32 when he founded Electronic Data Systems, as was Larry Ellison when he started Oracle. Gordon Moore was 39 and Robert Noyce 41 when they founded Intel. These latter numbers are much more like those of the famous founders of other industry sectors such as oil, electricity, aerospace, and television.

The success of exceptionally young entrepreneurs has continued into the cloud computing and social media era. Mark Zuckerberg was 19 when he started Facebook, as was Vitaly Buterin (born in Russia) when he founded Ethereum. Daniel Ek (who is Swedish) was 23 when he founded Spotify; Larry Page and Russia-born Sergei Brin were 25 when they founded Google. Kevin Systrom was 27 when he founded Instagram, as was Brian Cheskey when he founded Airbnb. Jack Dorsey founded Twitter when he was 29. Travis Kalanick was 32 when he founded Uber.

It was entirely predictable that these young men would surround themselves with relatively younger workers, for reasons of both skills and culture. Managers naturally hire people from the networks they have, and many young executives are understandably not fully comfortable supervising people who are their parents’ or grandparents’ age. And let’s face it, many older managers also choose to hire younger, cheaper workers. But over time, ages and hiring practices tend to revert to the norm. Tim Cook is 61; Jeff Bezos is 58; Satya Nadella is 54; and Sundar Pichai is 50. Increasingly, Big Tech will have an age profile not that different from other industry sectors, as the current crop of IT-savvy younger workers inevitably ages.

Areas of Tech Industry Leadership

Amidst all the race, gender and age criticism, the diversity achievements of the digital world go largely unmentioned. This is unfortunate, as the IT industry deserves high marks in at least three areas. First, the tech industry has long exhibited strong support of the LGBTQ community. Given that the technology industry is centered in urban areas such as San Francisco and Boston, that its workers are relatively young, and its politics relatively liberal, it’s probably not a coincidence that in 2014 Apple’s Tim Cook became the first CEO of a major U.S. corporation to be openly gay, an event that, happily, was both celebrated and seen as no big deal.

Similarly, has any industry done more to improve accessibility? Technology companies build devices and machines that help the visual and hearing impaired; they provide the type of work that does not require high levels of physical mobility; they have synthesized speech and enabled voice commands, and increasingly they are able to translate human thought into physical world actions to help the truly immobile. In addition to these tremendous quality-of-life improvements, these innovations have made it much easier for the disabled to effectively work across a wider share of the overall economy. Further accessibility advances are a virtual certainty.

Lastly, it’s easy to forget the terrible religious discrimination that characterized many professions during the 20th century, with subtle and not-at-all-subtle prejudices against Jews, Muslims, Catholics, Hindus, and pretty much anyone else that was not of the right Protestant stock. The digital world is a largely secular one, with relatively little interest in the religious divides of the past. If anything, the technology industry needs to improve its tolerance of the deeply devout, as well as those who are socially and politically conservative.

Still Work To Do

None of the above is meant to suggest that everything is fine, and that nothing needs to be done. Clearly, efforts to draw more students from the African-American and Hispanic communities must continue, and the digital world will benefit if it attracts and retains more women in many STEM fields. In both of these areas, the technology industry should recognize that as long as today’s imbalances persist, they can easily set in motion negative feedback loops. The fewer minorities that are hired, the weaker their networks and the more that stereotypes take hold. The fewer women, the more likely it is that bad behavior will proliferate, driving more women out of the field. The fewer older workers, the more uncomfortable those workers will be. The fewer minority-owned businesses, the fewer mentors and ties to the venture capital community. These cycles risk becoming entrenched, and thus need to be addressed.

Fortunately, many such efforts are now underway. Today, just about every major tech company has a significant diversity initiative; they also monitor their progress in this area much more systematically than they have done in the past, with many making public commitments, including targets, grants, scholarships, internships, fellowships, and leadership programs. There are equally important efforts outside of the vendor community. Organizations such as Black Girls Who Code, TechLatino, and the many nonprofits promoting IT to women demonstrate the sincere and widespread wish to create a more representative digital world.

Although such initiatives are not new, and there is no guarantee that they will succeed, the scale of today’s effort provides further evidence that a broad indictment of the technology industry is not justified. The extraordinary success of Indians and Asians shows that information technology is far from a Whites-only business. The relatively low presence of African-Americans and Hispanics in the IT industry closely resembles the situation in other STEM-based fields. The patterns in law, medicine, accounting, journalism, and other professions show that equality for women starts with the talent pipeline from leading universities, but this pipeline is still relatively weak in computer science and engineering. The younger-than-average digital workforce isn’t a bad thing in and of itself, and it will surely move closer to the norm over time. The technology industry’s strengths in supporting the LGBTQ community, increasing accessibility, and largely eliminating traditional forms of religious discrimination should be applauded. While greater diversity within hi-tech remains an unmet societal goal and ongoing industry challenge, critics of the digital world are significantly overstating their case.

About This Series

ITIF’s “Defending Digital” series examines popular criticisms, complaints, and policy indictments against the tech industry to assess their validity, correct factual errors, and debunk outright myths. Our goal in this series is not to defend tech reflexively or categorically, but to scrutinize widely echoed claims that are driving the most consequential debates in tech policy. Before enacting new laws and regulations, it’s important to ask: Do these claims hold water?

About the Author

David Moschella is a non-resident senior fellow at ITIF. Previously, he was head of research at the Leading Edge Forum, where he explored the global impact of digital technologies, with a particular focus on disruptive business models, industry restructuring and machine intelligence. Before that, David was the worldwide research director for IDC, the largest market analysis firm in the information technology industry. His books include Seeing Digital – A Visual Guide to the Industries, Organizations, and Careers of the 2020s (DXC, 2018), Customer-Driven IT (Harvard Business School Press, 2003), and Waves of Power (Amacom, 1997).

About ITIF

The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) is an independent, nonprofit, nonpartisan research and educational institute focusing on the intersection of technological innovation and public policy. Recognized by its peers in the think tank community as the global center of excellence for science and technology policy, ITIF’s mission is to formulate and promote policy solutions that accelerate innovation and boost productivity to spur growth, opportunity, and progress. For more information, visit itif.org.

Endnotes

[1]. “‘Defending Digital’ Series” (ITIF, January 2022), https://itif.org/publications/2022/01/10/defending-digital-series/.

[2]. Katie Reilly, “As the Harvard Admissions Case Nears a Decision, Hear From 2 Asian-American Students on Opposite Sides,” Time magazine, March 12, 2019, https://time.com/5546463/harvard-admissions-trial-asian-american-students/.

[3]. Sophie Andrews and Lucia Morris, “Diversity in CS: Race and gender among CS majors in 2015 vs 2020,” The Stanford Daily, August 8, 2020, https://stanforddaily.com/2020/08/08/how-has-diversity-within-stanfords-cs-department-changed-over-the-past-5-years/.

[4]. Jasmine Weiss, et al., “Medical Students’ Demographic Characteristics and Their Perceptions of Faculty Role Modeling of Respect for Diversity,” JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(6):e2112795. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.12795.

“Architect Demographics and Statistics in the US,” Zippia (accessed July 17, 2022), https://www.zippia.com/architect-jobs/demographics/

[5]. National Science Board, “Bachelor’s degrees awarded, by citizenship, field, race, and ethnicity: 2000–17,” Table S2-7 in Science & Engineering Indicators 2020, NSB-2019-7, September 4, 2019, https://ncses.nsf.gov/pubs/nsb20197/.

[6]. UC Berkely School of Information, “Changing the Curve: Women in Computing,” accessed July 17, 2022, https://ischoolonline.berkeley.edu/blog/women-computing-computer-science/.

[7]. National Science Foundation, “Women, Minorities, and Persons with Disabilities in Science and Engineering,” National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics (NCSES), Directorate for Social, Behavioral and Economic Sciences, accessed July 17, 2022, https://ncses.nsf.gov/pubs/nsf21321/report/field-of-degree-women.

[8]. Matt Asay, “Is tech getting older or less ageist? The answer is complicated,” TechRepublic, April 7, 2022, https://www.techrepublic.com/article/is-tech-getting-older-or-less-ageist-the-answer-is-complicated/.

Editors’ Recommendations

December 13, 2021

Podcast: The Keys to Diversifying Computer Science Education, With Dr. Juan Gilbert

February 24, 2016