Three Bills Show Remaining Divisions in Attempt to Reach a Compromise on Federal Data Privacy Legislation

Congress has been dragging its feet on passing comprehensive federal data privacy legislation, largely because members cannot agree on a number of divisive issues. A few bills have attempted to strike a compromise, though so far none have reached the floor. Three of these bills represent the different ways lawmakers have attempted to find a compromise on data privacy, so far without success. However, their similarities show how close Congress could be to passing federal data privacy legislation, and their differences show where the remaining battles lines exist.

First, Sen. Brian Schatz (D-HI) introduced the Data Care Act in March 2021; the bill attracted 18 Democratic co-sponsors but died in committee. Second, Sen. Maria Cantwell (D-WA) introduced the Consumer Online Privacy Rights Act (COPRA) in November 2021 with three Democratic co-sponsors (including Sen. Schatz); the bill also died in committee. Third and most recently, key members from both parties of the House and Senate Commerce Committees released a discussion draft of the American Data Privacy and Protection Act (ADPPA) on June 3, 2022.

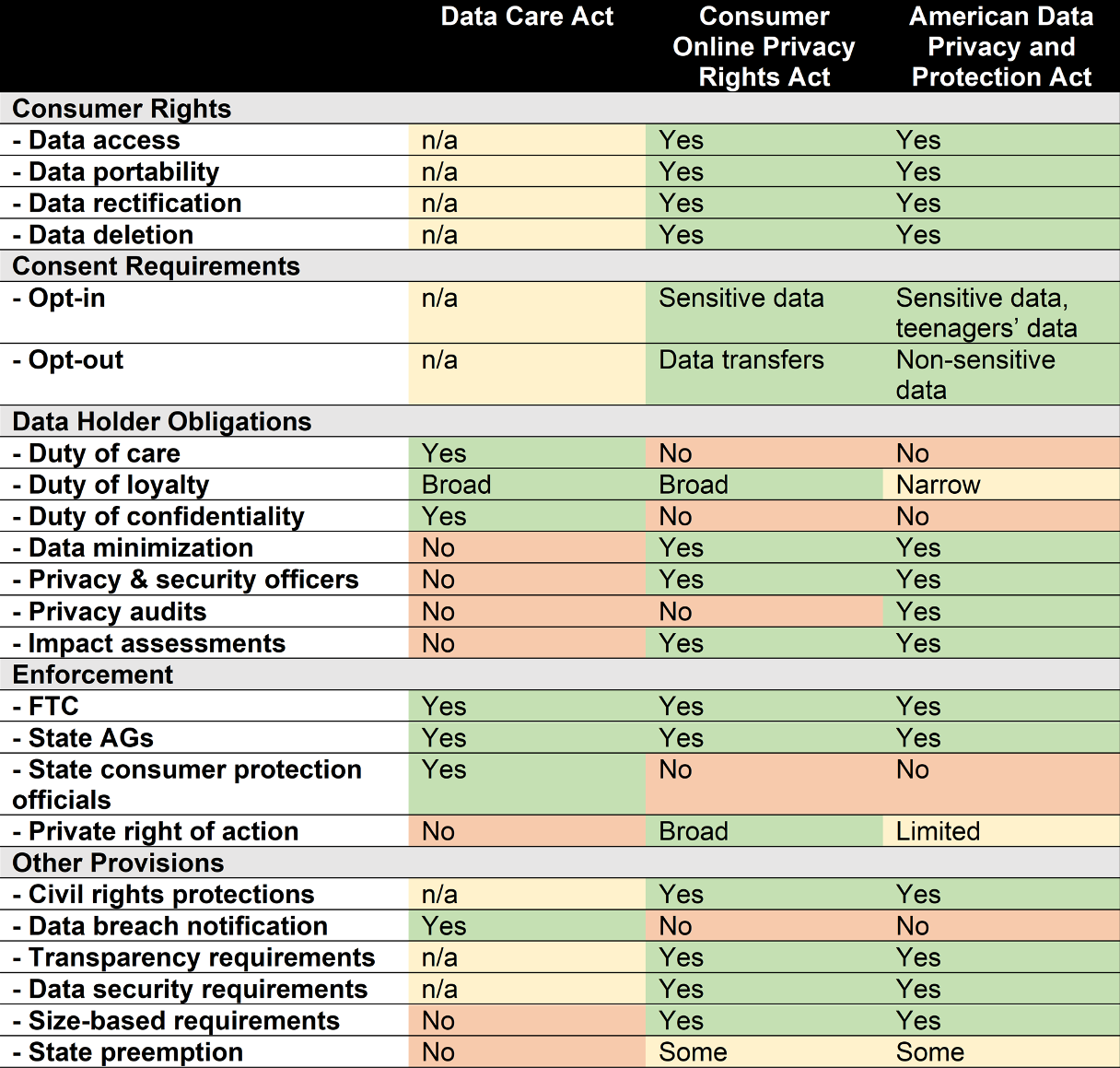

As shown in the table below, the three bills have some areas of overlap. All three establish certain requirements that data holders must meet and “duties” they must adhere to, with the intention of ensuring the privacy and security of user data, although the specific nature of these requirements varies. COPRA and ADPPA include a duty of loyalty, which restricts or prohibits certain data practices, whereas the Data Care Act includes a duty of loyalty, duty of confidentiality, and duty of care. The Data Care Act’s duty of confidentiality limits the ways in which data holders can disclose or sell individual identifying data, and the bill’s duty of care requires data holders to take “reasonable” steps to secure data from unauthorized access.

Even though all three bills contain a “duty of loyalty,” the specifics of that duty vary across each bill. Both COPRA and the Data Care Act broadly require that data holders not engage in any deceptive or harmful data practices that could cause injury to an individual or violate their privacy. In contrast, ADPPA enumerates specific generally prohibited practices, such as collecting, processing, and transferring, Social Security numbers, precise geolocation, passwords, Internet search history, physical activity, genetic information, and nonconsensual intimate images (with certain reasonable exceptions for each). ADPPA’s lack of broader duties is a sticking point for Sens. Schatz and Cantwell, with Schatz saying he will not vote for a privacy bill that does not include these obligations. However, Republicans have shown little interest in creating open-ended obligations on data holders.

All three bills include enforcement by both federal and state authorities: namely, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and state attorneys general, with the Data Care Act also enabling state consumer protection officials to enforce the law.

Finally, none of the bills preempt all contradictory state privacy laws. COPRA and ADPPA preempt some state laws, while the Data Care Act does not preempt any. This lack of complete preemption bears a cost: The costs of 50 different state privacy laws, each imposing their own different set of rules, could exceed $1 trillion over 10 years, with at least $200 billion hitting small businesses. One of the primary benefits of federal privacy legislation is the opportunity to create a uniform set of rules that applies across the country, greatly simplifying compliance. A federal privacy law that fails to do that would only further complicate the regulatory landscape.

COPRA and ADPPA share some additional similarities. Both give consumers the rights to data access, portability, rectification, and deletion. Both require data holders to hire and retain privacy and data security officers, and both include data minimization requirements, which require organizations to collect no more data than is necessary to meet specific needs. Data minimization requirements limit innovation by reducing access to data, limiting data sharing, and constraining the use of data.

COPRA and ADPPA also both include a private right of action, allowing individuals to sue data holders over violations, though ADPPA’s private right of action is more limited in scope. A private right of action is one of the most costly provisions a privacy law can contain. A federal privacy law containing a broad private right of action could cost up to $2.7 billion per year in duplicative enforcement. COPRA includes a broad private right of action, while ADPPA includes a more narrow one that would still open data holders up to frivolous lawsuits.

Finally, COPRA and ADPPA both include additional requirements for “large data holders” and some exemptions for small businesses. These size-based requirements contradict the argument that consumer privacy is important at every level. Violations of privacy are serious regardless of the size of the data holder, and every size of data holder is vulnerable to data breaches and other security threats.

Each of the three privacy bills contain a few unique provisions. The Data Care Act includes a data breach notification requirement, COPRA includes a civil rights provision that sets additional rules for the use of data related to certain protected characteristics, and ADPPA includes transparency requirements for data holders. COPRA requires opt-in consent, while ADPPA requires opt-in consent for sensitive data and teenagers’ data (ages 13 to 17) and opt-out consent for non-sensitive data.

Obtaining opt-in consent is significantly more expensive than obtaining opt-out consent, and has a greater impact on consumer productivity as users have to click through pop-up notices or sign contracts in order to give their consent and access content. Moreover, a broad opt-in requirement would deliver a significant blow to the ad-supported Internet economy because advertising revenues from targeted ads would decline significantly or costs to obtain consent would increase. This could result in more content that consumers have to pay for, hurting lower-income Americans especially. Opt-out consent still gives users control over how their data is collected and used, but places fewer barriers on both consumers and businesses.

Though there are areas of overlap, the differences between the Data Care Act, COPRA, and ADPPA represent some of the key sticking points in the debate over what provisions a federal privacy law should contain. These include matters such as provider duties, preempting state laws, a private right of action, and opt-out vs. opt-in consent.

Congress’ top priority as it seeks to pass comprehensive data privacy legislation should be striking the right balance between protecting consumer privacy without overly complicating compliance or restricting productivity and innovation. Current proposals are a mix of good and bad, but so far there has been a lack of serious debate and willingness to compromise that has prevented any of these proposals from reaching the floor.

Editors’ Recommendations

June 15, 2022

Children’s Privacy in Review: The Future of COPPA

October 25, 2018

Understanding Data Privacy

June 16, 2014