Anticorporate Progressivism: The Movement to Restrict, Restrain, and Replace Big Business in America

For many progressives, anticorporatism is not just the means for achieving other policy goals, it is the main goal in and of itself: an economy rid of large corporations. If their movement prevails, the result will be slower growth, diminished competitiveness, and less opportunity.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Key Takeaways

Contents

The Rise of Anticorporate Progressivism. 5

The Progressive Attack on Policies Enabling Bigness 11

Core Tactics Used by Anticorporate Progressives 18

How Should Supporters of a Pragmatic Agenda Respond? 23

Introduction

Opposition to globalization. Efforts to weaken intellectual property (IP) protections. Pushing for municipal broadband. Support for organic food. Calls for the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to develop drugs. What do these seemingly unconnected positions have in common? Simple: They all are suffused with a deep animus toward corporations and an equally fierce determination—among progressive activists and politicians—to transform the U.S. economic structure into one in which government-provided goods and services are readily available; small, locally-owned firms abound; and corporations are heavily regulated and broken up by the Justice Department whenever they get too big.

It is so-called “Big Tech” companies that face the most scrutiny these days from the media, advocacy groups, lawmakers, and regulators. But for most progressives, this anticorporatism extends well beyond the tech sector. It has become a general operating principle, the go-to policy formula for righting wrongs and achieving other societal goals—a conviction so firmly held that it is no longer just the means to an end; it is, for many, the end in and of itself.

This has not always been so. For more than a century, starting in the 1910s and continuing through to the 1990s, most progressives accepted that large corporations were a permanent and even valuable part of American economic life, to be balanced with other forces, such as unions, and sometimes to be regulated. Today, however, a growing share of progressives view large corporations as inherently problematic, if not malicious. To be sure, America faces serious challenges, such as excessive income inequality and a tattered safety net. But if we reject the calls of today’s anticorporate progressives and instead follow the examples of the original Bull Moose Progressives and most New Dealers, we can solve these problems in ways that do not diminish the value corporate capitalism produces for both the U.S. economy and American society itself.

Anticorporatism Now Extends From the Fringe to the Center of the Political Fabric

Over the last two decades, in parallel with the anticorporate Left’s growth from a relatively small fringe to a formidable political force, the criteria that progressives have used to determine whether policymakers are sufficiently liberal has shifted dramatically. Rather than evaluating policymakers on whether they support policies that generate progressive outcomes—getting broadband to rural areas, fostering drug development, addressing global warming, helping workers get training—they now judge policymakers almost exclusively on whether they advocate for positions that would restrict, restrain, or replace the corporate sector.

Very few on the anticorporate left will acknowledge that anticorporatism is their true goal, yet their disdain for those who shop at Walmart, get coffee at Starbucks, or patronize other large corporations, is palpable. They realize that while many voters may rightly support more regulation and more progressive taxation, most oppose shrinking the corporate sector, especially since half of private sector workers are employed by large companies. As a result, the anticorporate Left camouflages its real endgame by calling for policies that enjoy near-universal support: lower prices, more privacy, more fairness, more broadband, safer food, fighting climate change, cheaper drugs. But the policies they embrace as solutions are primarily designed to restrict, restrain, or replace the corporate sector—a silver-bullet solution, they believe, for all of the above, but also an end in and of itself. It happens to be the case that when it comes to advancing those and many other progressive goals, large corporations have a demonstrably better track record than small firms do, but that rarely enters into the debate.[1]

There has been an anticorporate fringe in American politics since large industrial corporations first emerged after the Civil War. Anticorporate sentiment has risen and fallen in relationship to economic conditions and political responsiveness. But today, that fringe extends toward the center of the fabric; as in many policy areas, it now represents mainstream thinking, particularly among Democrats. (There is an emerging anticorporate wing in the Republican party, too, but this report focuses on the anticorporatist Left.) Tying that agenda to the important goal of racial justice has made it even easier for the anticorporate Left to broaden its appeal by promulgating the false claim that small businesses better serve the interests of people of color.[2]

Most progressives, and many liberals, now have a deep and abiding animus toward large corporations, regardless of their behavior or how active their social responsibility efforts are. As such, these progressives seek to reshape the U.S. economy away from a corporate structure, which they see as inherently against the public interest. And in many ways, they are making progress, as evidenced by the fact that “Big” is now largely used as an epitaph (e.g., Big Cable, Big Pharma, Big Tech).

Most progressives, and many liberals, now have a deep and abiding animus toward large corporations, regardless of their behavior or how active their corporate social responsibility efforts are.

However, to achieve its goal of radically restructuring the U.S. economy, the anticorporate Left must first convince voters that in each industry, corporate performance is deficient (prices and profits are too high, innovation is too low, privacy too unprotected, workers earning too little, etc.) and that the technologies corporations develop and use come with an array of unacceptable risks and harms. Most of the claims along those lines are inaccurate or overstated, but they get recycled ad nauseum on social media anyway, in the press, and in congressional hearings, thus laying the groundwork for a set of structural anticorporate policies that, if implemented, would result in lower economic and wage growth, less innovation, reduced U.S. competitiveness, and reduced opportunities for disadvantaged Americans.

If policymakers are to advance effective policies to support competitiveness, economic growth, opportunity, and innovation across a wide array of areas, they need to understand the real nature of the debate: Do we want for-profit corporations competing with each other to drive innovation, progress, and American competitiveness—albeit with a system of government regulation and public spending—or do we want a system with government- and small business-provided goods and services, and wherever that is not possible, strict and costly regulations of large companies?

At its heart, this new version of progressivism is not so much about being antimarket as it is about being anticorporate, meaning, “opposed to or hostile toward corporations or corporate interests.”[3] This is not meant to suggest that there are not additional motivations that underpin anticorporate progressives’ positions. Opposing laws to limit digital piracy would limit large media companies’ revenues, but it also would deliver free content to “the people.” Supporting policies to reduce automobile use is not just about limiting the size of auto companies, it is about realizing progressives’ vision of how they believe everyone should live (in built-up urban areas). Nonetheless, the result of these and a wide array of other policies many progressives now seek would be to shrink the size and effective functioning of the corporate sector.

It is certainly true that corporations are a means to various ends. And if an economy with fewer large corporations could achieve important public interest goals better than can the current economy, then policymakers should support that path. But in a technology-driven, globalized economy, that is simply not the case. A healthy, productive, innovative (and responsible) corporate sector brings with it a host of critical public benefits: increasing per capita gross domestic product (GDP), good jobs, innovation, better goods and services, a cleaner environment, and national competitiveness.[4]

The alternative to an anticorporate agenda is a pragmatic agenda that focuses on where more government is needed to advance welfare and progress—and where corporations are needed to advance similar goals.

Likewise, an anti-anticorporate agenda is not an agenda that necessarily favors large corporations over small business. Contrary to the vision of anticorporate progressives who seek an economy dominated by small and mid-sized firms, optimal policy is size neutral, with government not tilting the balance in either direction but instead letting market forces determine the optimal business size and structure.

Nor is the alternative to an anticorporate agenda, as many progressives assert, an antigovernment agenda. The alternative to an anticorporate agenda is a pragmatic agenda that focuses on where more government is needed to advance welfare and progress—and where corporations are needed to advance similar goals. Indeed, as John Kenneth Galbraith noted, there are many aspects to capitalism that need countervailing. But countervailing does not mean counter to corporations themselves.

Finally, anticorporate progressives should not have a monopoly on progressive thought. There are a host of progressive policies, such as a higher minimum wage, expanded access to health care and retirement security, increased unionization, more clean energy, and more progressive taxes on individuals, that would help achieve important progressive goals without restricting, restraining, or replacing the corporate sector.

If we are to engage in a debate about the role of large corporations in America, then we should do so directly, by examining each industry and asking whether it would be better to have goods and services provided the way they are now or with fewer large corporations. And if the answer is the former, then what are the policies to maximize the public interest and ensure benefits for most Americans?

This report discusses how anticorporatism has evolved, how it plays out in various industries and technology policy areas, and what supporters of the current system need to do to avoid losing the battle, including more-effectively addressing the legitimate concerns of progressives.

The Rise of Anticorporate Progressivism

In the 1980s and 1990s, debates over advanced industries and technologies were mostly pragmatic and focused on the best ways to advance innovation and growth. Since then, additional players have joined the debate, bringing with them a variety of ideological aims, including protecting privacy, helping small business, promoting equity, and limiting the role of government. And in the last decade, this divergence has grown wider, with many liberals engaging in industry and technology policy debates to push for a fundamentally different kind of industry structure that significantly reduces the role of large corporations. Many progressives no longer see corporate-led business models as desirable, instead advocating for government production, small-business production and, as a last resort, heavily regulated corporations.

Progressives did not weave this extreme position out of whole cloth. Forty years of policy that let the interests of large corporations diverge from the national interest added to their frustration and anger. A system of “managerial capitalism” that before the 1980s balanced shareholder interests (particularly short-term interests) with stakeholder interests has evolved into a system of “shareholder capitalism” that pressures corporations to maximize short-term profits.

Former Defense Secretary Charles E. “Engine Charlie” Wilson famously said in a 1953 congressional hearing that “what’s good for the country is good for General Motors, and vice versa.” The growth of globalization since then has rendered that statement anachronistic.

The decline in organized labor in the private sector has significantly reduced countervailing pressure on corporations. Reducing taxes on the wealthy has let many wrongly conflate corporate income with the excess wealth of the “point-one percenters.”

Forty years of living in “the era of big government is over” underscores that government has failed to respond to the hosts of challenges generated by a technology-fueled, global economy, making it easier to attack corporations as the problem. For example, if the government funded the U.S. Economic Development Administration at the same share of GDP today as it did in 1979, then it would be receiving $51 billion a year, not $300 million.[5] Business leaders and elected officials used to understand that support for capitalism and big business depended not only on business serving U.S. interests but on government playing an active role to fill in the gaps, serve as a backstop, and invest in key foundations.

Finally, several decades of corporate scandals, including Enron’s accounting scandal, Tyco’s executive stock fraud, Goldman Sachs’s manipulation of derivative markets, Volkswagen’s “Dieselgate,” and Wells Fargo’s pressuring of employees to manipulate customers into adding accounts, have added fuel to the anticorporate fire. All of these trends and factors have led progressives to give up on the possibility of regulating and reforming corporations to maximize the public interest. Instead of reform, they now pursue revolution.

It’s not just “democratic socialists” such as Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT)—who said, “The task is to build an international movement of our own against capitalist elites”—and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) who embraces an anticorporate agenda.[6] That view has permeated liberal thinking.

As author Evan Osborne wrote in The Rise of the Anti-Corporate Movement, “Increasingly, the obstacles to everything that progressives believe in—decent health care and retirement for all through the welfare states, world peace, a clean environment—are being interpreted exclusively through the anti-corporate prism.”[7]

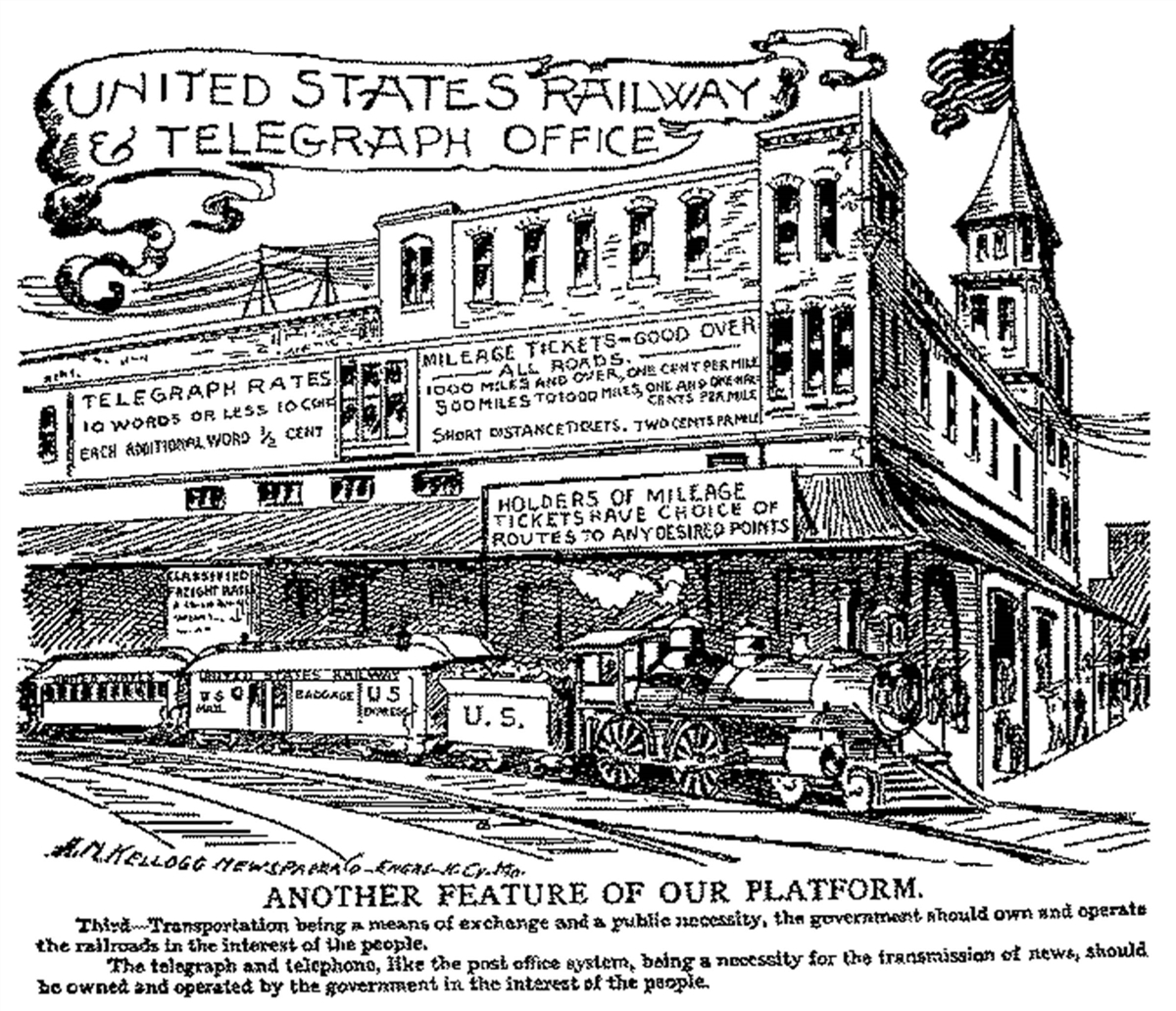

It wasn’t always this way. As the second wave of industrialization transformed America in the 1890s, populists were opposed to the change and fought against large, privately owned corporations. The Populist Party campaign platform from this period reflected this view, calling for nationalizing what we would today call “network industries”: rail, telephone, and telegraph. As historian of the era Robert Wiebe noted, “Through nationalization the populists expected to take certain basic segments of the economy from the “interests” and hand them to the “people.”[8] (See figure 1).

Figure 1: Populist Party poster calling for nationalization of railroads and telegraphs[1]

However, while populism was an expression of frustration, anger, and opposition to change, it was the progressive movement that came to grips with the economic reality. In reality, many of the original progressives were not anticorporate. Far from it. They often embraced industrialization and the rise of large corporations because they rightly understood that big business was the source of progress.

Herbert Croly, author of the progressive tract The Promise of American Life, and someone who is regularly spurned by conservatives today, wrote with respect to large corporations, “The new organization of American industry has created an economic mechanism which is capable of being wonderfully and indefinitely serviceable to the American people.”[9]

In his 1905 annual message to Congress, President Theodore Roosevelt declared,

I am in no sense hostile to corporations. This is an age of combination, and any effort to prevent combination will not be useless, but in the end vicious, because of the contempt for law which the failure to enforce law inevitably produces. We should, moreover, recognize in cordial and ample fashion the immense good effected by corporate agencies in a country such as ours, and the wealth of intellect, energy, and fidelity devoted to their service, and therefore normally to the service of the public, by their officers and directors.[10]

As Sean Wilentz wrote in The American Prospect with respect to President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Dealers, “In everything that mattered—an appreciation of the democratic potentials of industrial capitalism, an acceptance that the old yeoman America was dead and gone—they repudiated populism.”[11]

Progressives embraced industrialization and the rise of large corporations because they rightly understood that big business was the source of progress.

In other words, most progressives did not want to roll back the corporate economy, they wanted to grow it and align it more with broader public interests. As Teddy Roosevelt stated, “The corporation has come to stay, just as the trade union has come to stay. Each can and has done great good. Each should be favored so long as it does good. But each should be sharply checked where it acts against law and justice.”[12]

Figure 2: Cartoon of Teddy Roosevelt and trusts

Indeed, TR was not opposed to large corporations or “trusts,” he just opposed “bad ones.” To be sure, there was always tension in the progressive movement over the role of corporations. While TR accepted large corporations, President Woodrow Wilson (with his New Freedom vision) and Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis were more skeptical—and in the case of Brandeis, oppositional.[13] During FDR’s administration, many New Dealers, as exemplified by Adolf Berle, a member of his brain trust, were supportive of the corporate economy but wanted it more regulated and supplemented by government policies and programs. In contrast, other New Dealers such as antitruster Thurman Arnold attacked large corporations.

But Democratic politics after World War II were largely accommodationist toward large corporations. President John F. Kennedy may have wanted the big steel companies to roll back price increases, but he didn’t want to break them up. And President Lyndon Johnson saw big corporations as critical players in his war on poverty and in powering the country’s challenge Soviet domination.

Now, partly because its followers reject the possibility of real reform, today’s progressivism has evolved into something quite different. Progressives, rather than accepting the inevitability—and indeed desirability—of large corporations, now seek to shrink the corporate sector, replacing it with small firms, nonprofits or government. In particular, rather than see small business in Marxian terms as “petite bourgeoisie” (small capitalists), they see small business and workers as oppressed by big business.

This leads to an agenda that seeks to shrink or restrict the corporate role. The Roosevelt Institute has written, “A once-in-a-generation transformation has begun, and a new progressive worldview is ascendant. Policymakers are starting to understand that we must rebalance power in our economy and our democracy, and that government action—at the right scale and with the right structure—can get us there.”[14]

“Rebalance” means shrinking the corporate role, while “government action” means increasing the government’s role in the provision of goods and services. The Institute went on to state,

The [Biden] administration understands how reshaping markets with public power can counter extractive corporate power. For example, the plan “prioritizes support for broadband networks owned, operated by, or affiliated with local governments, non-profits, and co-operatives—providers with less pressure to turn profits and with a commitment to serving entire communities.” It acknowledges outright that subsidies do not suffice in distorted markets. That kind of approach should translate across sectors. (Emphasis added.)[15]

They want “more public goods” and to “curb corporate power.”[16] The progressive organization Liberation in a Generation goes even further, writing that “corporations and the people who run them are the architects and stewards of the Oppression Economy.” Therefore, they argue, “we must break up monopolies and reform the ways corporations are governed to limit their power.”[17]

Because of this underlying and pervasive class orientation (and now gender, race, and other identity orientation), many progressives view the interests of American and foreign workers as aligned.[18] In this framing, what’s good for foreign workers is good for U.S. workers, and vice versa, because U.S. corporate interests are presumed to be bad for both. This distorted framing—distorted if one considers oneself an American first and a citizen of the world second—leads many progressives to support policies such as weakening IP protection provisions in trade agreements, which would clearly enable foreign consumers to get cheaper goods and services, but would come at a cost to U.S. workers who make them because the firms they work for would generate fewer revenues. But this framing ignores the fact that large businesses employ half of all workers in the private sector, and it rejects any possible alignment of interests. This globalist orientation is also why so many progressives deny the reality of U.S. international competitiveness. They understand that if competitiveness is a real issue, then U.S. worker and corporate interests are tightly linked and policies such as a competitive tax code with incentives to invest in research and development (R&D) are needed.

Many of today’s progressives attack the U.S. economic model, characterized mostly by for-profit firms, and in many industries, large, efficient, and innovative firms.

There should be no mistake that this new progressivism is a natural evolution of the original progressivism articulated by leaders such as John Commons, Thorstein Veblen, Henry George, and Herbert Croly.[19] Many of today’s progressives attack the U.S. economic model, characterized mostly by for-profit firms, and in many industries, large, efficient, and innovative firms. Whether attacking “Big Broadband,” “Big Tech,” “Big Pharma,” or anything else that can be portrayed as “Big,” progressives no longer seek reform, but rather, transformation—fundamentally changing the U.S. economic system. K. Sabeel Rahman, president of the progressive “think and do tank” Demos, testified at a recent congressional hearing on Big Tech, delivering comments that exemplify the new progressivism: “Limiting this problematic form of private power requires rediscovering familiar but forgotten tools, including antitrust law, public utility-style regulation, and a willingness to consider cases where public control of key infrastructure would benefit the public rather than private provision.”[20]

To force its point, the anticorporate Left today frames the choice as between small-government, free-market advocates and anticorporate progressives. If you are not with them, then you must be a laissez-faire ideologue in the pocket of big business. But to borrow a term, there is a “third way”—in this case, a progressive philosophy and agenda that is neither anticorporate nor antigovernment.

To achieve their goal of transforming the U.S. economy, anticorporate progressives must first convince the media, thought leaders, and voters that the current corporate system is the original sin and rife with failure. They paint a picture of big firms, particularly in technologically advanced industries, as charging too much, profiting too much, innovating too little, and harming consumers and small businesses with their single-minded drive to accumulate profits. If progressives can convince enough voters, pundits, and policymakers of their views, then the path to enacting policies that undermine the current system becomes much easier.

The Progressive Attack on Policies Enabling Bigness

Anticorporate progressives are reflexively opposed to policies that might directly or indirectly enable bigness. They almost always couch their opposition to these policies in other terms (protecting consumers, encouraging competition, etc.). But their goal is always the same: to oppose policies that enable bigness. This plays out in a number of policy areas.

Generic Policy Areas

Trade

Anything that enables businesses to extend markets geographically enables larger firms. Before the Civil War and the rise of the railroad, most companies were small and local. But once the railroads emerged to knit together markets, larger and more efficient firms were able to gain larger markets, putting less-efficient local firms out of business. International trade enables even larger markets and scale. Now, for example, instead of having four large firms serve one national market, perhaps six much larger firms can serve a global market. Progressives understand this; it is why they oppose trade agreements and other policies that enable global integration. It’s also why progressive economist Joe Stiglitz wrote that we must “tame globalization,” which, among other things, means no more trade agreements.[21] It is why anticorporate progressives tout slogans such as “think globally, act locally,” which really mean embrace the interests of workers around the world but structure economies to be dominated by small firms serving local and regional markets. To advance this goal, they frame globalization as only serving the interests of large corporations, not workers and consumers.

Anticorporate progressives are reflexively opposed to policies that might directly or indirectly enable bigness. However, they almost always couch their opposition to these policies in other terms.

Transportation

Globalization enables scale because it opens up markets. Transportation enables scale because it enlarges markets. Because expanded transportation networks enable economies of scale, and thus larger firms, progressives oppose generally expanding mobility. They oppose expanding highways and ports and enabling more efficient trucks and freight rail. For example, the liberal Center for American Progress opposes building new highway capacity, instead favoring repaving existing roads and adding bike lanes and transit.[22] One liberal think tank advocates for transportation policies and programs that prioritize “regional linkages over national and global ones,” arguing that transportation has enabled industry consolidation.[23]

Intellectual Property

Most progressives seek to weaken IP protection and oppose laws and regulations, including in trade agreements, that enable rights holders to defend their IP. They claim that this is because they want to boost innovation or protect consumer rights. But the real reason is they know IP protection enables firms to scale. Several studies find that nations with stronger property rights, including IP rights, have larger firms. As one study finds, “An efficient legal system eases management’s ability to use critical resources other than physical assets as sources of power, which leads to the establishment of firms of larger size. It also protects outside investors better and allows larger firms to be financed.”[24]

Moreover, without strong IP protection, the government should be required to fund IP generation, as there is otherwise no market incentive to do so—which also plays into the anticorporatist goal of having government play a larger role in production.

This helps explain why most progressive organizations advocate for weakening IP protection. According to the progressive advocacy organization Public Knowledge,

[T]he United States should ensure that people can legally share content without being subjected to new IP barriers such as a broadcasting right. Emerging networks should not be constrained into a poor imitation of existing media merely to fit existing business models. The United States should oppose efforts to create new property rights in the transfer of information that would hinder the free flow of information.[25]

Similarly, it came as little surprise when progressives took advantage of the COVID-19 crisis to push their long-standing goal of weakening patent protection for drugs and called for IP rights for vaccine producers to be abrogated, even though most experts argued that this would do nothing to bring vaccines to the rest of the world faster.[26]

Taxes

Tax policy can shift the economy’s firm-size structure. This is one reason the standard business tax proposal from Democrats—especially progressives—is to cut taxes for small businesses while raising corporate taxes.[27] For example, President Biden’s tax proposal would establish a minimum tax for companies, but only for large corporations, exempting smaller corporations and noncorporate businesses.[28] In addition, while many progressives have historically supported tax provisions that allow businesses to expense in the first year for tax purposes expenditures made on capital equipment, they want to cap that at a modest amount so large firms get almost no benefit.

Spending

For almost a century, progressives have advocated for greater government spending than have conservatives, but mostly to fill in critical gaps. Today, progressives seek much larger government in order to shrink both the role of the corporate sector and our dependence on it. Their thinking is if more Americans can be dependent on government and the nonprofit sector funded by government and progressive foundations, they will embrace—or at least acquiesce to—an anticorporate agenda.

We see this is in the push by progressives for massive stimulus packages, including federal jobs programs. This is one reason why, when the unemployment rate was at a near historic low, that the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities called for a massive Federal jobs program ($543 billion in 2018), with jobs to be provided by state and local governments.[29] This is also why so many progressives support a universal basic income (UBI). They justify this as needed because automation will purportedly eliminate most jobs (something economists agree will not happen because of the increase in income and demand from automation). But in reality, UBI reduces people’s dependency on the corporate sector, including by enabling UBI recipients to start small businesses.[30] Progressives David Graeber and Nick Srnicek consider UBI as a way to free people from lives spent rowing overmanaged corporate galleons (as opposed to the delightful small business dinghies).[31]

Related to this are progressives’ calls to vastly expand spending to support the nonprofit sector, which they argue (incorrectly) provides better jobs than does the corporate sector.[32] Expanding government funding to nonprofits for health care, education, environmental protection, and other areas is a way to shrink the corporate sector.[33] Advocates trumpet that the nonprofit sector now employs more workers than manufacturing.[34]

Antitrust

Finally, antitrust. Over the last 15 years, progressives have become “neo-Brandeisians” who view virtually all economic problems as stemming from one cause: large corporations. This has led to a proliferation of progressive screeds against bigness: Tim Wu’s The Curse of Bigness; Matt Stoller’s Goliath: The 100 Year War Between Monopoly and Democracy; Jonathan Tepper’s The Myth of Capitalism: Monopolies and the Death of Capitalism; Zephyr Teachout’s Break ‘Em Up: Recovering our Freedom From Big Ag, Big Tech and Big Money; Barry Lynn’s Cornered: The New Monopoly Capitalism and the Economics of Destruction; and perhaps the book with the catchiest, if not the most eloquent title, Sally Hubbard’s Monopolies Suck: 7 Ways Big Corporations Rule Your Life and How to Take Back Control.

The neo-Brandeisian project is not to improve the economy with antitrust. It is to limit the size and economic influence of large corporations, regardless of whether this hurts or helps the economy, competitiveness, workers, and consumers.

These books almost all start with a description of an idealized world before the 1980s when corporations were supposedly much smaller and everyone else much better off. A host of economic problems since then are all laid at the feet of the purported rise of monopolies enabled by the emergence of a new corrupt school of antitrust that puts consumer welfare at the center of antitrust thinking. And like a three-act play, the finale involves the neo-Brandeisians coming in to save us and restoring some long-lost American dream by taking the antitrust hatchet to big, bad corporations.

To be clear, the neo-Brandeisian project is not to improve the economy with antitrust. If it were, it would not be against large firms just for being large. Its goal is to limit the size and economic influence of large corporations, regardless of whether it hurts or helps the economy, competitiveness, workers, and consumers.

Sector-Specific Policies

In their campaign against big corporations, anticorporate progressives attack a range of industries, seeking to advance policies that would either undermine the industry as a whole or the large firms in the sector.

Fossil Fuels

Perhaps no industry is vilified more by progressives than “Big Oil.” To be sure, we should be doing more to limit greenhouse gas emissions, including supporting alternatives to fossil fuels.[35] But progressives’ animus toward large oil and gas companies leads to positions, such as being opposed to carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies and nuclear energy, that are more about being anti-Big Oil and anti-“Big Utility” than pro-climate. If the world is to meet carbon reduction goals, CCS and nuclear will likely have to play a key role. Many progressives oppose CCS because it will enable Big Oil to continue. Environmental activist Bill McKibben opposes CCS because he opposes the oil industry itself.[36] The advocacy group 350.org also opposes CCS and advocates for 100 percent renewables and keeping oil “in the ground.”[37] Peggy Shepard, co-chair of the Biden White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council, also opposes CCS for similar reasons.[38] In other words, the goal is not limiting carbon emissions, which is what CCS would do, but to limit Big Oil’s production.[39] Some progressives even want the government to buy out and phase down oil and gas companies.[40] This animus toward Big Oil is also a reason why progressives put so much focus on energy efficiency, as it enables emissions reductions, mostly by supporting small, mom-and-pop construction companies.[41]

There is a similar animus toward nuclear power, even though it is a zero-GHG-emitting technology. One article describes opposition to nuclear power, “When we understand the white male effect, we can see the nuclear power industry through the eyes of others: with its very large, utility-owned power plants, the industry is the epitome of hierarchical worldviews.”[42] In other words, local communities aren’t going to install their nuclear power plants (unlike with solar panels)—only large electric utility corporations will.

As progressive activist Naomi Klein wrote in an article for The Nation, “Real climate solutions are ones that steer ... power and control to the community level, whether through community-controlled renewable energy, local organic agriculture, or transit systems genuinely accountable to their users.”[43] And they are ones that “reign in corporate power,” which means stopping CCS and nuclear.

Banking

“Break up the big banks” is a rallying cry for anticorporate progressives.[44] This is not because big banks are any more risky than small banks. After all, Canada has a few very large national banks, but they are tightly regulated.[45] Rather, it is because they don’t like big corporations. Anticorporate progressives advocate for small community banks.[46] Ideally, they would prefer public banks, including having the United States Postal Service (USPS) get into banking and providing free accounts.[47] They support having the government take over providing student loans for the same reason, and the creation of a public bank for financing infrastructure.[48]

Farming

“Big Agriculture” has become a term of derision, as when Greenpeace warns of “Corporate Control of Our Food.”[49] Despite the fact that large farms are more productive than small ones and play a key role in keeping food prices low, anticorporate progressives work to minimize the corporate farming sector. This is a major reason why the anticorporate progressives demonize genetically modified foods and favor organically grown foods.[50] They know that if they can pass laws that reduce consumption of nonorganic food, small farms will gain market share. This is also why they oppose agricultural subsidies for large farms but favor them for small farms, and why they support legislation banning certain large food operations.[51]

Broadband

Anticorporate progressives have targeted “Big Cable,” or as Sen. Ed Markey (D-MA) calls the industry, the “big broadband barons.”[52] They support policies that would reduce large broadband firms’ market share. This is the principal reason why anticorporate progressives work for such policies as regulating broadband such as telephony (under Title II of the Communications Act), subsidizing municipal broadband providers, funding smaller broadband providers to overbuild broadband where larger companies already provide it (by advancing the misleading claim that consumers need very fast symmetrical networks), advocating for spectrum policy that supports small and even very localized community carriers, and supporting price regulation and even free broadband.[53] It is also why they oppose policies that would help larger providers deploy broadband to more areas of the nation.[54] And why they advocate for wired and wireless broadband funding set-asides for small carriers. All of these policies are in service of their overarching goal: to drastically limit the market share of larger broadband providers.

Internet

Until the second term of the Obama administration, the Internet industry (e.g., Google, Facebook, Apple, etc.) was one of the few industries not demonized by the anticorporate left, in part because many of these companies supported progressive issues such as net neutrality and opposed online piracy legislation (e.g., the Stop Online Piracy Act and PROTECT IP Act, known as SOPA/PIPA). But even taking these positions could not keep them out of the anticorporate crosshairs for long.

Progressives now subject Internet companies to a regular stream of attacks, arguing that their technology is fundamentally biased, their platforms fail to take down content progressives disagree with, their devices intrusively surveil citizens’ private activities, and their applications put children at risk. Anticorporate progressives want to use antitrust to break up large Internet companies. They want to subject these firms to regulations and taxes other firms are not subject to.[55] They advocate for strict privacy laws in order to reduce the ad revenues of large Internet companies. Some have called for public or nonprofit search engines and social networks.[56]

Biopharmaceuticals

Anticorporate progressives oppose the system in which private companies, many of them large, create and sell drugs mostly by responding to market signals. They instead seek an industry with many fewer large firms wherein the government has a larger role in drug development. They try to achieve that by advocating for strict price controls, reduced patent protections to reduce company revenues, and increased government and university responsibility for drug discovery.[57]

For instance, Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT), as part of his campaign to become the 2020 Democratic presidential nominee, called for creation of a Medical Innovation Prize Fund that would launch a fund equal to 0.55 percent of GDP (more than $80 billion per year), with the federal government funding half and private health insurance companies the other half.[58] Liberal Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz has backed drug prizes, as has liberal U.S. economist Dean Baker of the Center for Economic and Policy Research, who has written that “a prize system would have enormous advantages over the current [life-sciences innovation] system.”[59] In other words, government would take over funding drug discovery to limit the role of biopharmaceutical companies, particularly large corporations.

Retail

Big box retailers (large retailers with a physical presence, such as Walmart, Target, Best Buy, and Home Depot) used to be the main retail targets of anticorporate progressives.[60] Today, the same anticorporate progressives who were calling for breaking up Walmart a decade ago have broadened their attack to “Big Internet” retailers, especially Amazon, forming an alliance of anticorporate groups devoted to only attacking Amazon and preventing the company from “preying” on small businesses.[61] They also seek regulations that only apply to large retailers, including local zoning limits on big box retailers, bans on cashless stores (something Amazon is piloting), and privacy rules that would particularly limit large retailers.[62]

Entertainment

Another target of the anticorporate movement is big entertainment companies, including music and movie studies—as exemplified by an article in the liberal journal American Prospect titled “It’s Time to Break up Disney.”[63] Anti-“Big” apostle Matt Stoller warns of the “Disney monopoly.”[64] And the Institute for Local Self Reliance wants to break up “Big Music.”[65] A key way to limit the market share of large movie studies and music recording companies is to oppose policies that crack down on content piracy, especially over the Internet.

Other Industries

Anticorporate progressives have turned their sights on a host of other industries, seeking policies to reduce the market share of large health insurance companies (supporting a single-payer system), credit reporting agencies, investment rating agencies, electric utilities,[66] airlines,[67] the chemical industry, hospitals,[68] human services,[69] defense,[70] and others.[71]

Technology Policies

Progressives’ campaign against large corporations is not just about policies that affect industries; it is about policies that enable technological innovation, a critical factor in bigness or smallness.

Unlicensed Spectrum

The use of radio spectrum is critical to the provisions of a host of services. There are two main ways of allocating the rights to use spectrum: licensed and unlicensed. Both are important to innovation. 5G will not happen without licensed spectrum, and continued innovations in Wi-Fi and related technologies require unlicensed spectrum. But because of the high cost of licensed spectrum—the last Federal Communications Commission (FCC) spectrum auction yielded over $81 billion in bids—large, well-capitalized firms are best positioned to win spectrum licenses.[72] As a result, most progressives oppose licensed spectrum as a way to starve large wireless providers of needed spectrum, and argue that anyone, especially local community wireless networks, should be able to use spectrum without paying.[73]

Open-Source Software

Because it has close to zero marginal costs (copies are free) and due to network effects, software is an industry that lends itself to scale. For anticorporate progressives, this is a problem—and why they so strongly advocate for “open source” software wherein source code can be inspected and changed by anyone.[74] They call for governments to procure open source and to provide tax credits for open-source development.[75] This is also a reason why so many progressives see Wikipedia—a nonprofit organization whose volunteers provide the content—as the model.

E-commerce

Anticorporate progressives oppose e-commerce because it enables scale (allowing retailers to reach much larger markets) and, as such, works against their vision of a local-shopkeeper economy. One progressive advocate wrote, “SMEs are the least likely to be able to compete with giant TNCs (transnational companies), which enjoy the benefits of scale, historic subsidies, technological advances, strong state-sponsored infrastructure, and a system of trade rules written by their lawyers. E-commerce in the WTO is a bait and switch.”[76] In that same vein, they call for trade rules that restrict e-commerce, and boycotts—or even breaking up—e-commerce companies such as Amazon.[77]

Anticorporate progressives oppose e-commerce because it enables scale and, as such, works against their vision of a local-shopkeeper economy.

Artificial Intelligence

AI is a technology that is more likely to be adopted by large companies, in part because they are more likely to have the skills, data, and technology available to make use of it, and also because of high fixed costs relative to marginal costs. This is one reason anticorporate progressives work to limit the technology, at least by large firms.[78] And it is why they attack AI for a host of purported harms, including exacerbating bias, violating privacy, killing jobs, spurring inequality, leading to killer weapons, and more.[79] In addition, the growing push for “ethical AI” and “AI for the public good” reflects an anticorporate view in the sense that it is based on the assumption that meeting consumer demand does not reflect the public, and market forces will not largely lead to companies selling AI services that are ethical.[80] As progressive academic Faisal A. Nasr noted regarding AI regulation, “Modulating the power of large technology companies is inherent in the legislative and regulatory reform that could take place, possibly prodded on by emerging social and civic innovation.”[81]

Rearguard Actions of Defense

The anticorporate Left not only fights to roll back the corporate sector; it also seeks to defend noncorporate institutions from incursion. Whether one agrees or disagrees with anticorporate progressives on each issue, the key point is that their goal is not necessarily a better policy outcome, but rather resisting corporatization of the economy. If free-market conservatives push privatization, then anticorporate progressives push publicization.

We see this in a wide variety of areas. Progressives fight to maintain, and even expand, the functions of the USPS against private sector providers such as UPS and FedEx, as well as against any efforts to enable privatization or work sharing of existing functions.[82] They oppose private provisioning of a wide variety of functions and infrastructure, including prisons, higher education, K–12 education, roads, utilities, and Social Security.[83]

Core Tactics Used by Anticorporate Progressives

To achieve their goal of a U.S. society and economy with significantly fewer and smaller corporations, anticorporate progressives engage in a variety of tactics.

Demonizing Large-Company Performance

Most Americans are pragmatic. They support the spirit of Deng Xiaoping, who said, in embracing capitalism, “We don’t care what color the cat is, as long as it catches mice.” As such, Americans are unlikely to support an anticorporate agenda just because progressives tell them they should. Anticorporate progressives know this, which is why most, with the exception of some activists such as Matt Stoller and Stacy Mitchell (who straight up argue against big corporations in favor of small business), ground their arguments not in shifting to small business but in attacking corporate performance. They couch their arguments in reforming corporations, not replacing them. If anticorporate progressives can convince enough Americans that large, for-profit corporations are destructive and harmful, then they believe they will get political support for their corrosive policies to shrink the corporate sector.

The charges are all too familiar. Prices and profits are too high. Corporations are hurting workers, consumers, small businesses, women and minorities, and the environment. Their service and product offerings are deficient, and they focus more on profits than innovation. And because of their “crony capitalist” lobbying, they are dependent on government anyway, so why not just have government provide goods and services?

If anticorporate progressives can convince enough Americans that large, for-profit corporations are destructive and harmful, then they believe they will get political support for their corrosive policies to shrink the corporate sector.

We see broad-scale industry attack in a number of areas. One is broadband. Most Americans obtain broadband from large Internet service providers not only because economies of scale enable lower costs, but because larger firms can best manage the technological complexities of running advanced and constantly improving communications networks. But to achieve their vision of a noncorporate broadband system, anticorporate progressives do everything possible to impugn the current, largely effective system. They argue, wrongly, that prices and profits are too high because of too little competition.[84] That everyone needs vastly higher broadband speeds than they actually do in order to make it appear that Big Broadband is scrimping on service.[85] They argue that large broadband providers just can’t wait to violate “net neutrality.” And that the successful intermodal competitive framework in the United States is inadequate.

We see the same anti-“Big” narrative applied to the pharmaceutical industry. In order to convince Americans to back a government-led drug development system, progressives argue wrongly that the industry is cutting R&D in favor of profits, new drug development has stalled, drug prices have grown dramatically, and the government plays a key role in drug development.[86]

Another way anticorporate progressives bolster their case against corporations is to frame issues as rights. In this narrative, Americans deserve cheap broadband, free health care, free drugs, free content, free Internet without providing any data, free public transit, free college, and a UBI without working. It is large, greedy corporations that stand in the way of this progressive utopia. If they can convince enough Americans of their basic right to lower-priced or even free goods and services, then Americans will come to demand government, since it is the only entity that can provide subsidies—paid for by expanding the national debt.

Figure 3: View of big business in the populist era

Against the vision of free goods and services provided by benevolent government agencies or nonprofits, they demonize corporations by singling out individual corporate malefactors as representative of the entire industry. When a small rural Internet service provider in North Carolina decided it didn’t want its customers to use Internet telephony since it would compete with the company’s voice business, this egregious policy held up an as example of what Big Broadband would do absent draconian net neutrality regulation. And when the reprehensible Martin Shkreli, who became CEO of Turing Pharmaceuticals and then jacked up the price of an HIV drug, progressives used the case to tar the entire biopharmaceutical industry. Corporate scandals are a gift to the anticorporate left—unfortunately, one the corporate sector has given too often.

Progressives also frame issues as a conflict between profits and people, trying to advance a narrative that anything that might increase a company’s profitability—boosting productivity, expanding market share, or developing new products, processes or business models—is bad for “the people.”

Related to this is their appropriation of the term “public interest” to make it seem that virtually everything that helps companies is by definition not in the public interest. For example, progressive advocacy group Public Knowledge has identified its mission: “We work to shape policy on behalf of the public interest.” For them, Charlie Wilson was wrong then and is wrong now: The interests of General Motors are antithetical to the public interest. We have, tragically, come to a time when what is good for GM under any circumstance can never be good for the nation.

Progressives frame issues as a conflict between profits and people, trying to advance a narrative that anything that might increase a company’s profitability is by nature bad for “the people.”

In this sense, this is a quasi-Marxist framework that holds out irreconcilable differences between capitalist and the proletariat. We see this framing play out in number of areas, including automation. For example, any time a company tries to boost productivity it is accused of putting profits before people. In reality, if companies did not try to boost productivity, living standards would stagnate.

Denying That Large Companies Produce Anything Beneficial

In 1952, the eminent scholar of business Peter F. Drucker observed,

We believe today, both inside and outside the business world, that the business enterprise, especially the large business enterprise, exists for the sake of the contribution which it makes to the welfare of society as a whole. Our economic-policy discussions are all about what this responsibility involves and how best it can be discharged. There is, in fact, no disagreement, except on the lunatic fringes of the Right and on the Left, that business enterprise is responsible for the optimum utilization of that part of society's always-limited productive resources which are under the control of the enterprise.[87]

As long as this is the case—that most people see that large corporations are producing benefits for the average person and society as a whole—they will generally support corporations. This gets to the key strategy of the anticorporate Left: claim that large companies produce harms, and deny large-company benefits.

They do that by engaging in a litany of attacks on corporations. They exploit workers, pollute the environment, put small businesses out of business, discriminate against minorities and women, cheat on taxes, fail to innovate, offshore jobs, earn too much in profits, charge too-high prices, contribute to inequality, and so on. However, large firms treat their workers far better than small firms do. They’re more innovative, contribute more to the economy, and have a better track record of advancing a host of other progressive goals.[88] Anticorporate progressives do everything they can to deny this reality because they understand how it weakens support for their anticorporate agenda. To be sure, stating this does not mean every corporation is a paragon of virtue or that there are not challenges regarding corporations that policy needs to address. But what it does mean is an anticorporate narrative about companies is a significant distortion of reality.

Decrying Alleged Structural Advantages

A key anticorporate narrative is that big corporations have all the advantages, and that the anticorporate community is the little David against the powerful Goliath. This certainly wins them sympathy, even if it is vastly overstated—if not wrong.

To be sure, corporations have advantages in the political sphere, principally in their ability to fund lobbying activities and support corporate political action campaigns (PACs). But these advantages are offset by a number of disadvantages.

First, there is a sizeable small business lobby, represented by organizations such as the National Association of Realtors, National Beer Wholesalers, National Auto Dealers Association, National Association of Insurance and Financial Advisors, the Credit Union National Association, and the National Federation of Independent Business. Moreover, on many issues, big businesses spend considerable political resources trying to disadvantage other big business competitors. All of this weakens the power of big corporations.

Second, while progressives want to frame big corporations as untamable leviathans, the reality is Schumpeterian creative destruction means that even the largest firms aren’t guaranteed survival if they fail to continually innovate—see Blockbuster and Kodak. Only 60 U.S. companies that were in the Fortune 500 in 1955 still were as of 2017.[89] According to a 2016 Innosight report, the average tenure in the S&P 500 had decreased to 20 years by 1990, and was on pace to shrink to just 14 years by 2026.[90] Indeed, about half of S&P 500 firms were likely to be relegated over the coming 10 years as the economy entered what the report called “a period of heightened volatility for leading companies across a range of industries … the most potentially turbulent in modern history.”[91]

Third, while the dominant narrative is that supporters of a corporate economy have financial advantages because of wealthy corporations, it ignores not only the limits of corporate largess, but also the significant financial resources on the anticorporate left.

The core weakness of corporations politically is that the same financial short termism that leads too many companies to scrimp on investments for the future also leads them to invest in political investments in the future, particularly investments related to collective action to preserve the entire system. As Henry Kissinger once famously stated, “Capitalists don’t know their own interests.”[92] Over the last four decades, U.S. corporate leaders have for the most part stopped acting like capitalists (e.g., leaders who work to defend the overall capitalist system) and more as managers who work to defend their own firm’s interest in the short run.

Corporations have advantages in the political sphere, principally in their ability to fund lobbying activities, and support corporate political action campaigns (PACs). But these advantages are offset by a number of disadvantages.

At the same time, rich liberals and foundations—including virtually all the major foundations—provide massive amounts of funding to anticorporate organizations. Consider the anticorporate organization Free Press, whose major mission is to limit large communications companies. In 2019, it had a budget of over $5.2 million dollars (including their affiliated 501c4 organization).[93] Free Press can boast, “We don’t take money from business, government or political parties and rely on charitable foundations and individual donors like you to power our work.”[94] But what that hides is most of their funding comes from large foundations, with a very liberal, often anticorporate focus. Their 2019 IRS 990 form lists contributions of $1.5 million, $850,000, $750,000, and $350,000. In 2017, it received funding from a number of progressive, often anticorporate, foundations, including the Ford Foundation, the Benjamin Fund, the Democracy Fund, the Foundation to Promote an Open Society, and the Woodcock Foundation.[95]

Free Press is just one organization. There are many other, often single-purpose anticorporate advocacy groups that receive the lion’s share of their funding from progressive sources. For example, the Roosevelt institute, which has led the charge on using antitrust to break up U.S. companies, receives funding from the Ford Foundation and MacArthur Foundation.[96] Likewise, the Democracy Alliance is a network of liberal donors who fund the Alliance, which in turn funds a variety of liberal organizations, some of which are anticorporate in their orientation, such as Demos, People’s Action, and Working Families. The Hopewell Fund, a 501c(3) that funds an array of progressive groups, some of them with an anticorporate focus, reported almost $87 million in revenue in 2019.[97]

Fourth, many academics have embraced anticorporatism in the last decade or so, seeing their mission not as objective, scholarly analysis but as fighting for a noncorporate economy.[98] Academics now routinely write jeremiads against corporations and the market economy. For example, in many areas of technology policy, academics no longer even pretend to be objective, as we see with the work of scholars such as Susan Crawford, Tim Wu, Zephyr Teachout, Shoshana Zuboff, and Joy Buolamwini.

Finally, bad corporate actors are a giant gift to the anticorporate Left. When companies such as Wells Fargo, BP, Volkswagen, Turing Pharmaceuticals, Enron, and Equifax violate the public trust either by venality or carelessness, it provides the anticorporate Left with valuable ammunition to claim that these are not “bad apples” but rather a reflection of “all the corporate apples.”

How Should Supporters of a Pragmatic Agenda Respond?

Unless those who favor a pragmatic agenda push back against the current anticorporate movement by applying pressure across the political spectrum, it will continue to progress, ultimately weakening the U.S. economy. Supporting the current system does not mean supporting all current policies, or even opposing needed “progressive reforms.” What it does mean is supporting an economy in which large, responsible corporations play a central role.

There are several ways pragmatists should respond.

Challenging Anticorporate Progressives’ Claim That They Support Capitalism and Markets

Anticorporate opponents know that most Americans do not agree with their agenda, which is why the cloak it with claims of being for capitalism and markets. As progressive economist Joe Stiglitz wrote,

I prefer another name, “progressive capitalism,” to describe the agenda of curbing the excesses of markets; restoring a balance among markets, government and civil society; and ensuring that all Americans can attain a middle-class life. The term emphasizes that markets with private enterprise are at the core of any successful economy, but it also recognizes that unfettered markets are not efficient, stable or fair.[99]

Stiglitz’s phraseology is reminiscent of Xi Jinping’s assertion that China’s Communist Party state-directed and dominated economy is nothing more than a “socialist market economy with Chinese characteristics.”[100] Likewise, in a speech decrying big business and praising small, Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) stated, “I love markets! Strong, healthy markets are the key to a strong, healthy America.”[101] This is a common refrain from anticorporate progressives. The message is not only that an economy with big firms is not a market economy, but that they are supporters of business. Advocates also know that if they can frame a noncorporate economy as the true capitalist economy, it will be harder to criticize them for attacking the U.S. economic system.

Directly Taking on Distorted or Misleading Arguments and Claims

A core tactic of the anticorporate Left is to paint the performance of the current system as deficient, and in particular to argue that large firms are the cause of a host of maladies. In most cases, their arguments are contradicted, or at least weakened, by both data and logic. For example, anticorporate progressives constantly repeat the claim that the share of income going to workers is down, implying that it is because profits are up. However, federal government data does not bear this out.[102] Likewise, they claim that industry concentration has reached crisis levels, justifying their calls for antitrust to break up “Big Everything.” Federal government data does not bear this out.[103] They claim profits have grown significantly. Federal data does not bear this out.[104] This is not to say that every claim they make about the economy is wrong or even exaggerated, but many are.

The problem, of course, is that once these claims are out in the wild, they become accepted fact, endlessly repeated by pundits, journalists, and politicians. Mark Twain purportedly stated that “a lie can travel halfway around the world while the truth is still putting on its shoes.” And this is the case with these half-truths and falsehoods. They exist in the echo chambers that pass for policy debate. Progressives cite these distortions over and over again. And a media that is overworked and understaffed is often not in a position to adequately assess the validity of the claims or even to review the arguments rebutting them. So, going forward, a key will be for defenders of the current system to confront distortions promptly and vigorously.

A core tactic of the anticorporate Left is to paint the performance of the current system as deficient, and in particular to argue that large firms are the cause of a host of maladies.

Highlighting the Costs of an Anticorporate Agenda

Most Americans are pragmatic. As such, if they are convinced that moving to a less-corporate economy is in their interests, many will support such a move. But the converse is also true. If they understand that such a move would impose real costs—less innovation, higher prices, less consumer choice, lower wages and productivity growth, and less international competitiveness—most Americans would resoundingly say no. This means that supporters of the current economy need to do a better job pointing out the benefits of corporate scale.

Rejecting the False Choice of Laisse-Faire Capitalism or Anticorporate Progressivism

The anticorporate Left knows that if it can define the political economy as a choice between Milton Friedman-like libertarians and their own anticorporate agenda, many Americans will support their agenda. And indeed, in a world characterized by hyper-globalization and increased income inequality, the latter is an appealing choice.

But that is not the choice. There are many flavors of Republican and Democratic economic doctrines. On the Republican side, there are still Republican moderates, as exemplified by the Republican Main Street Partnership.[105] And a new Republicanism embraced by leaders such as Senator Marco Rubio (R-FL) and thought leaders such as American Compass’s Oren Cass.[106] On the Democratic side of the aisle, the moderate New Democrat Caucus is the largest House caucus, and there is still a tradition of labor-based progressives that accept the role of corporations but want to ensure progressive policies such as support for unions, appropriate regulation, and more progressive taxation.

Supporting the Right Reforms

Finally—and this gets to a key point: Anticorporate advocates have been around since the rise of the industrial corporation in the late 1800s, but they usually only become ascendent when the political system fails to address critical challenges.[107] This failure leads to the embrace of more radical approaches. The dominance of free-market and small-government thinking in Washington over the last 40 years has sowed the field for the reemergence of the anticorporates.

This means that if corporations want to prevent anticorporate populism from achieving even more of its goals, they will need to support the right kinds of progressive reforms. And to be clear, individual firm responses to particular issues, such as making statements about racial justice, while important, will not be enough, as they mostly overlook other key issues, (e.g., whether firms are investing in America, for the long-term, etc.) and do nothing to address broader system challenges. Nor will embracing ESG (environmental, social, and governance) practices and investing be considered enough. Companies will have to move beyond narrow ESG to support progressive reforms that are not anticorporate. One place to start is with support for raising the minimum wage. If anything, this is pro-corporate, since most companies paying minimum wages are small business, not corporations.

The dominance of free-market and small-government thinking in Washington over the last 40 years has sowed the field for the reemergence of the anticorporates.

Even more importantly, corporations need to step up and support reform of the financial system to roll back the financialization of the economy, with its dire consequences for income inequality, wasted resources, and distortions of investment time horizons by corporations and the sometimes-predatory asset stripping by private equity. We need to get back to a world wherein finance serves production, not the other way around.

Unless capitalism advances public interest goals, including productivity and innovation, it will lose support. The Business Roundtable’s recent statement on redefining the purpose of the corporation away from shareholder primacy toward a recognition of broader stakeholder interests is a needed first step—but that statement should have also made clear that a key stakeholder is the nation and its interests, which includes increasing advanced production in the United States. In addition, the statement needs to be backed by support for the right policy actions.[108]

The efforts in the 1970s to “save capitalism,” as exemplified by the famous Powell memo, written to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce by future Supreme Court Justice Lewis Powell, succeeded in galvanizing many businesses, wealthy donors. and the political Right overall, and that in turn helped a successful pushback of anticapitalist policies. But it also meant that many system problems (growth of income inequality, hollowing out of manufacturing, regional economic disparities, lack of health care coverage, better family leave policies, etc.) were never addressed because the advocates believed that either free markets alone would address them or they were simply not problems. Thus, while those efforts may have won one battle, they sowed the seeds of the anticorporate movement we see today.

This is a challenge because the U.S. corporate community, and more broadly the business community, has lost the ability to effectively act as an overarching interest. As one article notes,

It’s a business-wide issue, and they’re all looking out for their own narrow interests ... Business rarely lobbies as a whole ... Success has fractured them. When there was a lot at stake, it was easy to unify. They felt like they were up against Big Government and Big Labor. But once you don’t have a common enemy, the efforts become more diffuse ... There’s not a sense of business organized as a responsible class.[109]

With so much pressure from Wall Street for short-term returns, companies are pressured to keep their head down and focus on their own firm interests, and to some extent their own industry interests, but much less so the interests of the overall corporate system. On top of that, on many issues, corporate interests diverge from noncorporate interests, with many independent businesses not only opposing needed progressive reforms such as a higher minimum wage and increased top marginal individual rates, but also actively lobbying against big corporations they rightly see as competitors.

To prevent the political dominance of a new kind of anticorporate progressivism, corporations need to embrace a set of progressive goals consistent with a national developmentalist framework.

So, to prevent the political ascendency of anticorporate progressivism, corporations need to embrace a set of progressive goals, including those consistent with a national developmentalist framework. As Michael Lind and I wrote,

National developmentalism rejects the moral vision of libertarianism—a global market of individuals with no significant local or national attachments—as alien to human nature. It also rejects the moral vision of progressive localism, with its self-reliant yeoman farmers and artisans and shopkeepers, as anachronistic in the industrial era. Local communities are important, but in the modern world military security and economic efficiency can be secured only by national economies anchored by large corporations.[110]

This means making a stronger effort to grow domestic operations, while at the same time being lead advocates for a robust national industrial policy, to make it more likely that corporations expand investment and jobs in the United States.

Corporations need to do more to support policies addressing income inequality, not through higher corporate taxes—which are anticorporate and would do almost nothing to reduce inequality, as the result would be mostly higher prices and less competitiveness—but rather higher taxes on the wealthy, capital gains, and dividend income, and limits on CEO and other executive compensation.

The corporate sector, at least the nonfinancial corporate sector, needs to push for strong financial sector reform to roll back the financialization of the economy, and with it the pernicious effect of corporate short-termism.

Companies need to also support a different kind of globalization, one in which they press the government to push back against foreign mercantilist practices, including currency manipulation, which have hurt American workers. At the same time, we need stronger private sector unions in the United States, as in their heyday, they played a strong role as countervailing power to corporations.

Form Left-Right Alliances

Increasingly, the Left and the Right are embracing anticorporatism, but for markedly different reasons. Some on the Right oppose corporations because they believe that they have embraced progressive “wokism,” which they see as a threat to the core values of the Republic. Some see corporations as enmeshed in a system of so-called “crony capitalism” that violates free-market dictates. And still others, as President Trump exemplified, distrust corporations for being too globalized and not patriots focused on American interests.

If we are to keep the anticorporate agenda from succeeding, those supportive of the role of corporations in the economy will need to work more closely together. Given the leftward shift in American politics and the importance of addressing at least some of the issues the anticorporate Left works to make hay out of, the onus is more on conservative organizations to move more toward the center and create a stronger alliance with moderates and even the few pro-corporate liberals that are left. Absent that alliance, it will be much easier for anticorporate forces on the Right and the Left to prevail in their agenda.

This new alliance should be pragmatic and not opposed to government efforts that might supplant (or support) a corporate role. A case in point is the Ex-Im Bank. Unlike proposals to have USPS get into the banking business, the goal of Ex-Im is not to replace the corporate banking sector. It’s to fill in gaps and help corporations export. And it should be an agenda that addresses the very real complaints that true progressives have. For absent that, the anticorporate voices will continue to grow.

Large corporations—and small innovative start-ups that want to become large—continue to play a major role in U.S. innovation, job creation, competitiveness, and advancement of living standards.

Conclusion

The American economy became the world’s leading economy because it, more than any other economy in the world, embraced large corporations—or at least allowed them to emerge and grow. Large corporations—and small innovative start-ups that seek to become large—continue to play a major role in U.S. innovation, job creation, competitiveness, and improved living standards.

Yet, progressives increasingly want to roll back the corporate sector and create an economy dominated by government, nonprofits, and small business. And where they can’t achieve that, they want large corporations singled out for heavy economic and social regulation. They are seldom forthright about this being their real goal; instead, they shroud it in a host of other claims and arguments. If policymakers want to shrink the corporate sector, then they should engage in an open and honest debate about that. If they want to achieve other goals (e.g., economic growth, privacy, transportation mobility, etc.), then they should understand, and reject, the anticorporate Left’s agenda.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the following individuals for helpful comments on earlier drafts: Randolph Court, Stephen Ezell, David Hart, and Michael Lind.

About the Author

Robert D. Atkinson (@RobAtkinsonITIF) is the founder and president of ITIF. Atkinson’s books include Big Is Beautiful: Debunking the Myth of Small Business (MIT, 2018), Innovation Economics: The Race for Global Advantage (Yale, 2012), Supply-Side Follies: Why Conservative Economics Fails, Liberal Economics Falters, and Innovation Economics Is the Answer (Rowman Littlefield, 2007), and The Past and Future of America’s Economy: Long Waves of Innovation That Power Cycles of Growth (Edward Elgar, 2005). Atkinson holds a Ph.D. in city and regional planning from the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

About ITIF

The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) is an independent 501(c)(3) nonprofit, nonpartisan research and educational institute that has been recognized repeatedly as the world’s leading think tank for science and technology policy. Its mission is to formulate, evaluate, and promote policy solutions that accelerate innovation and boost productivity to spur growth, opportunity, and progress. For more information, visit itif.org/about.

Endnotes

[1]Robert D. Atkinson and Michael Lind, Big Is Beautiful: Debunking the Myth of Small Business (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, March 2018), ISBN: 9780262037709.

[2]Robert D. Atkinson, “Reality Check: Facts About Big Versus Small Businesses” (ITIF, March 2021), https://itif.org/publications/2021/03/12/reality-check-facts-about-big-versus-small-businesses.

[3]“Anti-corporate,” definition of Anti-corporate by Merriam-Webster, accessed June 3, 2021, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/anti-corporate.

[4]Atkinson and Lind, Big Is Beautiful: Debunking the Myth of Small Business.

[5]Rob Atkinson, “It’s Time to Bring Back Place-Based Policymaking,” American Compass, May 24, 2021, https://americancompass.org/the-commons/its-time-to-bring-back-place-based-policymaking/.

[6]Aparna Gopalan, “(How) Should Class War Go Global? Building an Anti-Corporate Left Internationalism,” Current Affairs (September/October 2020), https://www.currentaffairs.org/2020/12/how-should-class-war-go-global-building-an-anti-corporate-left-internationalism.

[7]Evan Osborne, The Rise of the Anti-Corporate Movement: Corporations and the People who Hate Them (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2009).